| |

| Category | Serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Old-style |

| Designer(s) | William Caslon I |

| Foundry | Caslon Type Foundry |

| Variations | Many |

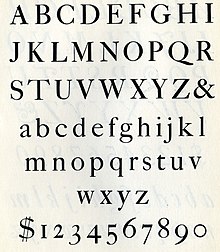

| Shown here | Adobe Caslon by Carol Twombly |

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I (c. 1692–1766) in London, or inspired by his work.

Caslon worked as an engraver of punches, the masters used to stamp the moulds or matrices used to cast metal type. He worked in the tradition of what is now called old-style serif letter design, that produced letters with a relatively organic structure resembling handwriting with a pen. Caslon established a tradition of engraving type in London, which previously had not been common, and was influenced by the imported Dutch Baroque typefaces that were popular in England at the time. His typefaces established a strong reputation for their quality and their attractive appearance, suitable for extended passages of text.

The letterforms of Caslon's roman, or upright type include an "A" with a concave hollow at top left and a "G" without a downwards-pointing spur at bottom right. The sides of the "M" are straight. The "W" has three terminals at the top and the "b" has a small tapered stroke ending at bottom left. The "a" has a slight ball terminal. Ascenders and descenders are relatively short and the level of stroke contrast is modest in body text sizes. In italic, Caslon's "h" folds inwards and the "A" is sharply slanted. The "Q", "T", "v", "w" and "z" all have flourishes or swashes in the original design, something not all revivals follow. The italic "J" has a crossbar, and a rotated casting was used by Caslon in many sizes on his specimens to form the pound sign. However, Caslon created different designs of letters at different sizes: his larger sizes follow the lead of a type he sold cut in the previous century by Joseph Moxon, with more fine detail and sharper contrast in stroke weight, in the "Dutch taste" style. Caslon's larger-size roman fonts have two serifs on the "C", while his smaller-size versions have one half-arrow serif only at top right.

Caslon's typefaces were popular in his lifetime and beyond, and after a brief period of eclipse in the early nineteenth century returned to popularity, particularly for setting printed body text and books. Many revivals exist, with varying faithfulness to Caslon's original design. Modern Caslon revivals also often add features such as a matching boldface and "lining" numbers at the height of capital letters, neither of which were used in Caslon's time. William Berkson, designer of a revival of Caslon, describes Caslon in body text as "comfortable and inviting".

History

Caslon began his career in London as an apprentice engraver of ornamental designs on firearms and other metalwork. According to printer and historian John Nichols, the main source on Caslon's life, the accuracy of his work came to the attention of prominent London printers, who advanced him money to carve steel punches for printing, first for foreign languages and then, as his reputation developed, for the Latin alphabet. Punchcutting was a difficult technique and many of the techniques used were kept secret by punchcutters or passed on from father to son. Caslon would later follow this practice, according to Nichols teaching his son his methods privately while locked in a room where nobody could watch them. As British printers had little success or experience of making their own types, they were forced to use equipment bought from the Netherlands, or France, and Caslon's types are therefore clearly influenced by the popular Dutch typefaces of his period. James Mosley summarises his early work: "Caslon's pica ... was based very closely indeed on a pica roman and italic that appears on the specimen sheet of the widow of the Amsterdam printer Dirck Voskens, c.1695, and which Bowyer had used for some years. Caslon's pica replaces it in his printing from 1725…Caslon's Great Primer roman, first used in 1728, a type that was much admired in the twentieth century, is clearly related to the Text Romeyn of Voskens, a type of the early seventeenth century used by several London printers and now attributed to the punch-cutter Nicolas Briot of Gouda." Mosley also describes several other Caslon faces as "intelligent adaptations" of the Voskens Pica.

Caslon's type rapidly built up a reputation for workmanship, being described by Henry Newman in 1733 as "the work of that Artist who seems to aspire to outvying all the Workmen in his way in Europe, so that our Printers send no more to Holland for the Elzevir and other Letters which they formerly valued themselves much." Mosley describes Caslon's Long Primer No. 1 type as "type with generous proportions and it was normally cast with letter-spacing that was not too tight, characteristics that are needed in types on a small body. And yet it is so soundly made that words that are set in it keep their shape and are comfortably readable...It is a type that works best in the narrow measure of a two-column page or in quite modest octavos." Caslon sold a French Canon face he did not engrave that may to have been the work of Joseph Moxon with some modifications, and his larger-size faces follow this high-contrast model. He publicised his type through contributing a specimen sheet to Chambers' Cyclopedia, which has often been cut out by antiquarian book dealers and sold separately.

Compared to the more delicate, stylised and experimental "transitional" typefaces gaining ground in mainland Europe during Caslon's life, notably the romain du roi type of the previous century, the work of Pierre-Simon Fournier in Paris, Fleischmann in Amsterdam and the Baskerville type of John Baskerville in Birmingham that appeared towards the end of Caslon's career, Caslon's type was quite conservative. Johnson notes that his 1764 specimen "might have been produced a hundred years earlier". Stanley Morison described Caslon's type as "a happy archaism".

While not used extensively in Europe, Caslon types were distributed throughout the British Empire, including British North America, where they were used on the printing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. After William Caslon I’s death, the use of his types diminished, but had a revival between 1840–80 as a part of the British Arts and Crafts movement.

Besides regular text fonts, Caslon cut blackletter or "Gothic" types, which were also printed on his specimen. These could be used for purposes such as title pages, emphasis and drop caps. Bold type did not exist in Caslon's time, although some of his larger-size fonts are quite bold.

One criticism of some Caslon-style typefaces has been a concern that the capitals are too thick in design and stand out too much, making for an uneven colour on the page. Printer and typeface designer Frederic Goudy was a critic: "the strong contrast between the over-black stems of the capitals and the light weight stems in the lower-case...makes a 'spotty' page". He cited dissatisfaction with the style as an incentive for becoming more involved in type design around 1911, when he created Kennerley Old Style as an alternative.

Eclipse

Caslon's types fell out of interest in the late eighteenth century, to some extent first due to the arrival of "transitional"-style typefaces like Baskerville and then more significantly with the growing popularity of "Didone" or modern designs in Britain, under the influence of the quality of printing achieved by printers such as Bodoni. His Caslon foundry remained in business at Chiswell Street, London, but began to sell alternative and additional designs. His grandson, William Caslon III, broke away from the family to establish a competitor foundry at Salisbury Square, by buying up the company of the late Joseph Jackson. Justin Howes suggests that there may have been some attempt to update some of Caslon's types towards the newer style starting before 1816, noting that Caslon type cast by the 1840s included "a handful of sorts, Q, h, ſh, Q, T and Y, which would have been unfamiliar to Caslon, and which may have been cut at the end of the eighteenth century in a modest attempt to bring Old Face up to date. The h, ſh and T are to be seen 1816, large parts of which appear to have been printed from well-worn standing type."

Even as Caslon's type largely fell out of use, his reputation remained strong within the printing community. The printer and social reformer Thomas Curson Hansard wrote in 1825:

At the commencement of the 18th century the native talent of the founders was so little prized by the printers of the metropolis, that they were in the habit of importing founts from Holland, ...and the printers of the present day might still have been driven to the inconvenience of importation had not a genius, in the person of William Caslon, arisen to rescue his country from the disgrace of typographical inferiority.

Similarly, Edward Bull in 1842 called Caslon "the great chief and father of English type."

Return to popularity

Interest in eighteenth-century printing returned in the nineteenth century with the rise of the Arts and Crafts movement, and Caslon's types returned to popularity in books and fine printing among companies such as the Chiswick Press, as well as display use in situations such as advertising.

Fine printing presses, notably the Chiswick Press, bought original Caslon type from the Caslon foundry; copies of these matrices were also made by electrotyping. From the 1860s new types began to appear in a style similar to Caslon's, starting from Miller & Richard's Modernised Old Style of c. 1860. (Bookman Old Style is a descendant of this typeface, but made bolder with a boosted x-height very unlike the original Caslon.) The Caslon foundry covertly replaced some sizes with new, cleaner versions that could be machine-cast and cut new swash capitals.

In the United States, "Caslon" became almost a genre, with numerous new designs unconnected to the original, with modifications such as shortened descenders to fit American common line, or lining figures, or bold and condensed designs, many foundries creating (or, in many cases, pirating) versions. By the 1920s, American Type Founders offered a large range of styles, some numbered rather than named. The hot metal typesetting companies Linotype, Monotype, Intertype and Ludlow, which sold machines that cast type under the control of a keyboard, brought out their own Caslon releases.

According to book designer Hugh Williamson, a second decline in Caslon's popularity in Britain did, however, set in during the twentieth century due to the arrival of revivals of other old-style and transitional designs from Monotype and Linotype. These included Bembo, Garamond, Plantin, Baskerville and Times New Roman.

Caslon type again entered a new technology with phototypesetting, mostly in the 1960s and 1970s, and then again with digital typesetting technology. There are many typefaces called "Caslon" as a result of that and the lack of an enforceable trademark on the name "Caslon", which reproduce the original designs in varying degrees of faithfulness.

Many of Caslon's original punches and matrices survived in the collection of the Caslon company (along with many replacement and additional characters), and are now part of the St Bride Library and Type Museum collections in Britain. Copies held by the Paris office of the Caslon company, the Fonderie Caslon, were transferred to the collection of the Musée de l'Imprimerie in Nantes. Scholarly research on Caslon's type has been carried out by historians including Alfred F. Johnson, Harry Carter, James Mosley and Justin Howes.

Metal type versions

Caslon Old Face

The H.W. Caslon & Sons foundry reissued Caslon’s original types as Caslon Old Face from the original (or, at least, early) matrices. The last lineal descendant of Caslon, Henry William Caslon, brought in Thomas White Smith as a new manager shortly before Caslon's death in 1874. Smith took over the company and instructed his sons to change their surnames to Caslon in order to provide an appearance of continuity. The foundry operated an ambitious promotional programme, issuing a periodical, "Caslon's Circular". It continued to issue specimens from top printers including George W. Jones until the 1920s.

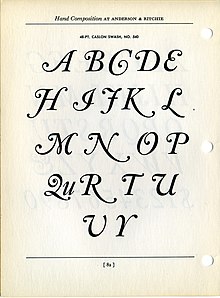

Some Caslon faces were augmented by adding new features, in particular swash capitals for historicist printing. From around 1887 the type was sold with additional swash capitals. Howes describes these as "based rather closely on François Guyot's italic of around 1557...found in English printing until the early years of the eighteenth century." From around 1893 the company started to additionally recut some letters to make the type more regular and create matrices which could be cast by machine. Due to the cachet of the Caslon name, some of the recuttings and modifications of the original Caslon types were apparently not publicly admitted. The H.W. Caslon company also licensed to other printers matrices made by electrotyping, although some companies may also have made unauthorized copies.

In 1937, the H.W. Caslon & Sons foundry was also acquired by Stephenson Blake & Co, who thereafter added "the Caslon Letter Foundry" to their name.

The hot metal typesetting companies Monotype and Linotype offered "Caslon Old Face" releases that were based (or claimed to be based) on Caslon's original typefaces. Linotype's has been digitised and released by Bitstream.

Caslon 471

Caslon 471 was the release of the "original" Caslon type sold by American Type Founders. American Type Founders advertised it as "the Caslon Oldstyle Romans and Italics precisely as Mr. Caslon left them in 1766. It was apparently cast from electrotypes held by American Type Founders' precursors. Thomas Maitland Cleland drew a set of additional swash capitals.

Caslon 471 is generally not available in digital forms as of 2022.

Caslon 540

Caslon 540 was a second American Type Founders version with shortened descenders to allow tighter linespacing. The italic was distributed by Letraset with a matching set of swashes, as a result revivals of this typeface are sometimes sold without a regular style (see below). The very distinctive ampersand in the italic is often used alone and mixed in with other typefaces in settings where no other characters from Caslon 540 are employed.

Digital revivals of Caslon 540 are sold by Bitstream, Linotype, and ParaType. The ParaType version includes Cyrillic characters. These revivals are sold with only the regular and italic styles and without any other weights. However, the same foundries also market Caslon Bold (i.e., Caslon 3) and its italic as separate products. Furthermore, Elsner+Flake, ITC, and URW sell the italic style without its upright style.

Caslon 3

A slightly bolder version of Caslon 540, released by American Type Founders in 1905. Digital revivals of Caslon 3 (also called Caslon Bold) are sold by Bitstream, Linotype, and ParaType. The ParaType version has Cyrillic glyphs.

Caslon Openface

A decorative openface serif typeface with very high ascenders, popular in the United States. Despite the name, it has no connection to Caslon: it was an import of the French typeface "Le Moreau-le-Jeune", created by Fonderie Peignot in Paris as part of their Cochin family, by ATF branch Barnhart Brothers & Spindler. Digital revivals are sold by Bitstream and Monotype.

The Monotype Corporation (UK)

The British Monotype company produced three Caslon revivals.

- 1903, Series 20, Old Face Special

- 1906, Series 45, Old Face Standard

- 1915, Series 128 & 209, Caslon & Caslon Titling.

Imprint

Main article: Imprint MTA more regular adaptation of Caslon by the British branch of Monotype was commissioned by the London publishers of The Imprint, a short-lived printing trade periodical that published during 1913. It had a higher x-height and was intended to offer an italic more complementary to the roman. It has remained popular since and has been digitised by Monotype.

Ludlow Typograph Company, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Ludlow had a wide variety of Caslon-types.

Caslon 641

A heavy version of Caslon 540, released by American Type Founders in 1966.

Caslon 223 and 224

Caslon 223 and 224 were phototypesetting families designed by Ed Benguiat of Lubalin, Smith, Carnase and then ITC. Like many ITC families, they have an aggressive, advertising-oriented bold structure, not closely related to Caslon's original work. 223 was the first version (named for LSC's street number), a companion version with more body text-oriented proportions followed sequentially numbered 224.

Digital-only releases

Adobe Caslon (1990)

Adobe Caslon is a very popular revival designed by Carol Twombly. It is based on Caslon's own specimen pages printed between 1734 and 1770 and is a member of the Adobe Originals programme. It added many features now standard in high-quality digital fonts, such as small caps, old style figures, swash letters, ligatures, alternate letters, fractions, subscripts and superscripts, and matching ornaments.

Adobe Caslon is used for body text in The New Yorker and is one of the two official typefaces of the University of Virginia and the University of Southern California. It is also available with Adobe's Typekit programme, in some weights for free.

Big Caslon (1994)

Big Caslon by Matthew Carter is inspired by the "funkiness" of the three largest sizes of type from the Caslon foundry. These have a unique design with dramatic stroke contrast, complementary but very different from Caslon's text faces; one was apparently originally created by Joseph Moxon rather than Caslon. The typeface is intended for use at 18pt and above. The standard weight is bundled with Apple's macOS operating system in a release including small caps and alternates such as the long s. Initially published by his company Carter & Cone, in 2014 Carter revisited the design adding bold and black designs with matching italics, and republished it through Font Bureau. It is used by Boston magazine and the Harvard Crimson.

LTC Caslon (2005)

LTC Caslon is a digitisation of the Lanston Type Company's 14-point size Caslon 337 of 1915, in turn a revival of the original Caslon types. This family include fonts in regular and bold weights, with fractions, ligatures, small caps (regular and regular italic only), swashes (regular italic weight only), and Central European characters. A notable feature is that like some hot metal releases of Caslon, two separate options for descenders are provided for all styles: long descenders (creating a more elegant designs) or short (allowing tighter linespacing).

To celebrate its release, LTC included in early sales a CD of music by The William Caslon Experience, a downtempo electronic act, along with a limited edition upright italic design, "LTC Caslon Remix".

King's Caslon (2007)

King's Caslon is a modern interpretation of Caslon created for King's College London and released by Dalton Maag. The typeface has a text version with two weights (Regular and Bold), in addition to a display version, each of which has its respective italic.

The text styles of King's Caslon have a lower level of contrast between strokes than most earlier Caslon revivals, while the display styles have more contrast.

Williams Caslon Text (2010)

A modern attempt to capture the spirit of Caslon by William Berkson, intended for use in body text. Although not aimed at being fully authentic in every respect, the typeface closely follows Caslon's original specimen sheet in many respects. The weight is heavier than many earlier revivals, to compensate for changes in printing processes, and the italic is less slanted (with variation in stroke angle) than on many other Caslon releases. Berkson described his design choices in an extensive article series.

Released by Font Bureau, it includes bold and bold italic designs, and a complete feature set across all weights, including bold small caps and swash italic alternates as well as optional shorter descenders and a "modernist" italic option to turn off swashes on lower-case letters and reduce the slant on the "A" for a more spare appearance. It is currently used in Boston magazine and by Foreign Affairs.

A notable feature of Caslon's structure is its widely splayed "T", which can space awkwardly with an "h" afterwards. Accordingly, an emerging tradition among digital releases is to offer a "Th" ligature, inspired by the tradition of ligatures in calligraphy, though not a historical type ligature, to achieve tighter letterspacing. Adobe Caslon, LTC Caslon, Williams Caslon and Big Caslon (italics only, in the Font Bureau release) all offer a "Th" ligature as default or as an alternate. King′s Caslon does not provide the "Th" ligature.

Distressed revivals

A number of Caslon revivals are "distressed" in style, adding intentional irregularities to capture the worn, jagged feel of metal type.

ITC Founder's Caslon (1998)

ITC Founder's Caslon was digitized by Justin Howes. He used the resources of the St Bride Library in London to thoroughly research William Caslon and his types. Unlike previous digital revivals, this family closely follows the tradition of building separate typefaces intended for different sizes. Distressing varies by style, matching the effect of metal type, with large optical sizes offering the cleanest appearance.

This family was released by ITC in December 1998. Following the original Caslon types, it does not include bold typefaces, but uses old style figures for all numbers.

H. W. Caslon version

Following the release of ITC Founder's Caslon, Justin Howes revived the H.W. Caslon & Company name, and released an expanded version of the ITC typefaces under the Founders Caslon name.

Caslon Old Face is a typeface with multiple optical sizes, including 8, 10, 12, 14, 18, 22, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 60, 72, 96 points. Each font has small capitals, long esses and swash characters. The 96 point font came in roman only and without small capitals. Caslon Old Face was released in July 2001.

Caslon Ornaments is a typeface containing ornament glyphs.

These typefaces are packaged in the following formats:

- Founders Caslon Text: Caslon Old Face (8, 10, 12, 14, 18), Caslon Ornaments.

- Founders Caslon Display: Caslon Old Face (22, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 60, 72), Caslon Ornaments.

- Founders Caslon 1776: Caslon Old Face (14), Caslon Ornaments. A selection of the types used on the United States Declaration of Independence.

However, following the death of Justin Howes, the revived H.W. Caslon & Company went out of business. Howes bequeathed all rights to the H. W. Caslon version to St Bride Library in London.

NotCaslon (1995)

An exuberant parody of Caslon italics created by Mark Andresen, this 1995 Emigre font was created by blending together samples of Caslon from "bits and pieces of dry transfer lettering: flakes, nicks, and all".

Franklin Caslon (2006)

This 2006 creation by P22 is based on the pages produced by Benjamin Franklin circa 1750. It has a distressed appearance.

Caslon Antique

Main article: Caslon Antique

This decorative serif typeface was originally called Fifteenth Century, but later renamed Caslon Antique. It is not generally considered to be a member of the Caslon family of typefaces, because its design appears unrelated, and the Caslon name was only applied retroactively.

Notes

- Arabic numerals in Caslon's time were written as what are now called text figures, styled with variable height like lower-case letters.

- Mosley identifies other non-Caslon types as the Samaritan and Syriac, and "it is difficult to believe that the lower case of the Small Pica no. 1...can be Caslon's work unless it is an early attempt. It was replaced in 1742, the only one of the roman types to be abandoned in this way." After the typesetting of this specimen Caslon cut an additional "Pica No. 2" and Pearl-size.

- "Elzevir" is a somewhat meaningless term meaning small types used by the Elzevir or Elsevier family of printers. Mosley concludes that in practice the term meant more "crisp, competent presswork" than the work of any specific engraver, since the Elseviers often used types cut centuries before in Paris.

- Apparently sensing a business opportunity, the Fry Foundry set up in business offering copies of John Baskerville's types in the late eighteenth century, but (apparently finding this unsuccessful given preference for Caslon amongst conservative British printers) began also to issue copies of Caslon's types "with such accuracy as not to be distinguished from those of that celebrated Founder".

- Note, however, some replacement sorts, including a Baskerville-style Q and open italic "h", both in the style of the late eighteenth century. Justin Howes suggests that these were attempts to modernise Caslon's type towards newer styles.

- The modern family Quarto by Hoefler & Frere-Jones is a well-received revival of the Dutch display types that inspired Caslon’s larger sizes, and is therefore quite similar.

- It is not to be confused with a totally different "Caslon FB" by Jill Pichotta, inspired by bold condensed Caslon-inspired typefaces used in American newspaper headlines.

References

- ^ Mosley, James (1967). "The Early Career of William Caslon". Journal of the Printing Historical Society: 66–81.

- Carter, Harry (1965). "Caslon Punches: An Interim Note". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 3: 68–70.

- ^ Howes, Justin (2000). "Caslon's punches and matrices". Matrix. 20: 1–7.

- ^ Mosley, James (2008). "William Caslon the elder". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Macmillan, Neil (2006). An A-Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press. pp. 63–4. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

- Loxley, Simon (12 June 2006). Type: The Secret History of Letters. I.B.Tauris. pp. 28–37. ISBN 978-1-84511-028-4.

- Alexander S. Lawson (January 1990). Anatomy of a Typeface. David R. Godine Publisher. pp. 169–183. ISBN 978-0-87923-333-4.

- Dodson, Alan. "A Type for All Seasons". Matrix. 12: 1–10.

- Dodson, Alan (2003). "Caslon- a Lively Survival". Matrix: 62–71.

- ^ Tracy, Walter (January 2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D.R. Godine. pp. 56–59. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

- "John Lane & Mathieu Lommen: ATypI Amsterdam Presentation". YouTube. ATypI. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Carter, Harry (1937). "Optical scale in type founding". Typography. 4. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Paul Shaw (April 2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 79–84. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6.

- ^ Haley, Allan. "Bold type in text". Monotype. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Berkson, William. "Reviving Caslon, Part 2". I Love Typography. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ Lane, J.A. (1 January 1993). "The Caslon Type Specimen in the Museum Van Het Boek". Quaerendo. 23 (1): 78–79. doi:10.1163/157006993X00235.

We now know that Caslon moved from Old Street to Chiswell Street in 1737/8. As far as we know, all of the Chiswell Street specimens dated "1734" were issued in various editions of the Chambers' Cyclopedia from 1738 to 1753.

- ^ Mosley, James (2003). "Reviving the Classics: Matthew Carter and the Interpretation of Historical Models". In Mosley, James; Re, Margaret; Drucker, Johanna; Carter, Matthew (eds.). Typographically Speaking: The Art of Matthew Carter. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 35. ISBN 9781568984278. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Mosley, James (1981). "A specimen of printing types cut by William Caslon, London 1766; A facsimile with introduction and notes". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 16: 1–113.

- Haley, Allan (1992). Typographic milestones (. ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 31. ISBN 9780471288947.

- Nichols, John (1782). Biographical and Literary Anecdotes of William Bowyer, Printer, F.S.A. and of Many of His Learned Friends,: Containing an Incidental View of the Progress and Advancement of Literature in this Kingdom, from the Beginning of the Present Century to the End of the Year 1777. Author. pp. 316–9, 537, 585–6.

- John Nichols (1812). Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century: Comprizing Biographical Memoirs of William Bowyer, Printer, F.S.A., and Many of His Learned Friends; an Incidental View of the Progress and Advancement of Literature in this Kingdom During the Last Century; and Biographical Anecdotes of a Considerable Number of Eminent Writers and Ingenious Artists; with a Very Copious Index. author. pp. 355 etc.

- Musson, A.E. (2013). Trade Union and Social History. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 138. ISBN 9781136614712.

- Downer, John. "The Art of Founding Type". Emigre. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Johnson, A. F. (1939). "The 'Goût Hollandois'". The Library. s4-XX (2): 180–196. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XX.2.180.

- Mosley, James. "Type and its Uses, 1455-1830" (PDF). Institute of English Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

Although types on the 'Aldine' model were widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries, a new variant that was often slightly more condensed in its proportions, and darker and larger on its body, became sufficiently widespread, at least in Northern Europe, to be worth defining as a distinct style and examining separately. Adopting a term used by Fournier le jeune, the style is sometimes called the 'Dutch taste', and sometimes, especially in Germany,'baroque'. Some names associated with the style are those of Van den Keere, Granjon, Briot, Van Dijck, Kis (maker of the so-called 'Janson' types), and Caslon.

- Johnson, Alfred (1936). "A Note on William Caslon" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 35 (4): 3–7. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Jan Middendorp (2004). Dutch Type. 010 Publishers. pp. 21–2. ISBN 978-90-6450-460-0.

- de Jong, Feike; Lane, John A. "The Briot project. Part I". PampaType. TYPO, republished by PampaType. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Ball, Johnson (1973). William Caslon, Master of Letters. The Roundwood Press. p. 346.

- Mosley, James. "Elzevir Letter". Typefoundry (blog). Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Mosley, James. "A lost Caslon type: Long Primer No 1". Type Foundry (blog). Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- Johnson, A.F. Type Designs. pp. 52–3.

- Morison, Stanley (1937). "Type Designs of the Past and Present, Part 3". PM: 17–81. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Sherman, Nick; Mosley, James (5 July 2012). "The Dunlap Broadside". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Old English Text MT". MyFonts. Monotype. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- Goudy, Frederic (1946). A half-century of type design and typography. New York: The Typophiles. pp. 67, 77. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Smith, John (1787). The Printer's Grammar (1787 ed.). pp. 271–316. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

Since the first appearance of Smith's Printers Grammar, and Mr. Luckombe's History of Printing, many very useful improvements have been made in the Letter Foundery of Messrs. Fry and Son, which was begun in 1764, and has been continued with great perseverance and assiduity, and at a very considerable expense. The plan on which they first sat out, was an improvement of the Types of the late Mr Baskerville of Birmingham, eminent for his ingenuity in this line, as also for his curious Printing, many proofs of which are extant, and much admired: But the shape of Mr. Caslon's Type has since been copied by them with such accuracy as not to be distinguished from those of that celebrated Founder…The following short Specimen may serve to convey some idea of the Perfection to which that Manufactory is arrived.

- Mosley, James. "Comments on Typophile thread". Typophile. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

In about 1770 the Fry foundry, whose first types in the 1760s were what they called an 'improvement' of Baskerville's, had also made an imitation of the smaller sizes of the Caslon Old Face types – a very close copy that is not easy to tell from the original. In 1907 Stephenson, Blake had recast this Caslon look-alike from original matrices and began to sell it under the name of Georgian Old Face.

- Eliason, Craig (October 2015). ""Transitional" Typefaces: The History of a Typefounding Classification". Design Issues. 31 (4): 30–43. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00349. S2CID 57569313.

- Mosley, James. "The Caslon Foundry in 1902: Selections from an Album". Matrix. 13: 34–42.

- A specimen of printing types. Wm. Caslon. 1798. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Mosley, James (2004). "Jackson, Joseph (1733–1792)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14539. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hansard, Thomas Curson (1825). Typographia, an Historical Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Art of Printing. p. 348. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Hints and Directions for Authors in Writing, Printing and Publishing Their Works. Edward Bull. 1842. pp. 33–5.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Recasting Caslon Old Face". Type Foundry. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Ing Freeman, Janet (1987). "Founders' Type and Private Founts at the Chiswick Press in the 1850s". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 19–20: 63–102. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Alfred F. (1931). "Old-Face Types in the Victorian Age" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 30 (242): 5–14. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- "Caslon" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 452.

- ^ Ovink, G.W. (1971). "Nineteenth-century reactions against the didone type model - I". Quaerendo. 1 (2): 18–31. doi:10.1163/157006971x00301. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Pichotta, Jill. "Caslon FB". Font Bureau. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- Specimen Book & Catalogue. American Type Founders. 1923. pp. 130–191, 780. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ "Williams Caslon Text–an overview of OpenType layout features" (PDF). Font Bureau. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Williamson, Hugh (1956). Methods of Book Design. Oxford University Press. pp. 85–98 etc.

- Mosley, James. "The materials of typefounding". Type Foundry. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Specimens of Type. London: H.W. Caslon & Co. 1915. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Tracy, Walter (1991). "The Alternatives". Bulletin of the Printing Historical Society (30).

- Millington, Roy (2002). Stephenson Blake: the last of the Old English typefounders (1st ed.). New Castle, Del. : Oak Knoll Press pp. 167 etc. ISBN 9780712347952.

- "Caslon Old Face". MyFonts. Bitstream. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Haley, Allan (15 September 1992). Typographic Milestones. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 31–39. ISBN 978-0-471-28894-7.

- 1923 American Type Founders Specimen Book & Catalogue. Elizabeth, New Jersey: American Type Founders. 1923.

- "Berthold Caslon 471 in use - Fonts In Use". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon 540 Font (Bitstream)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon #540 Font (Linotype)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon 540 Font (ParaType)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ "Caslon Bold Font (Bitstream)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ "Caslon #3 Font". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ "Caslon Bold Font (ParaType)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon 540 EF Font". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon #540 Font (ITC)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon #540 Font (URW)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon 3 LT". MyFonts. Linotype. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- Devroye, Luc. "Le Moreau-le-Jeune: A Typographical Specimen with an Introduction by Douglas C. Murtrie". Type Design Information. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Kupferschmid, Indra (9 November 2012). "Caslon Openface". Alphabettes. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- "Moreau-le-jeune". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- "Caslon Open Face". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- "Caslon Openface Font (Bitstream)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- "Caslon Open Face Font (Monotype)". Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- Stanley Morison (7 June 1973). A Tally of Types. CUP Archive. pp. 24–7. ISBN 978-0-521-09786-4.

- McKitterick, David (2004). A history of Cambridge University Press (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521308038.

- "Imprint MT". MyFonts. Monotype. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Silverman, Randy (December 1994). "Carol Twombly on Type". Graphic Arts. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Adobe - Fonts : Adobe Caslon". Store1.adobe.com. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- Hill, Will (2005). The Complete Typographer: A Manual for Designing with Type (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Person Prentice Hall. p. 53. ISBN 9780131344457.

- Haley, Allan (1997). "Adobe Caslon: A New Interpretation". Step-by-Step Graphics: 108–113.

- Gopnik, Adam (February 9, 2009). "Postscript". The New Yorker. p. 35.

- "Official Typefaces | USC Identity Guidelines | USC". identity.usc.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Big Caslon promotional page". Font Bureau. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "Big Caslon - Desktop font « MyFonts". New.myfonts.com. 2000-01-01. Archived from the original on 2009-01-18. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- "Big Caslon FB". Font Bureau. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Buchanan, Matthew. "Quarto Review". Typographica. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Quarto". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Big Caslon". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "LTC Caslon MyFonts". MyFonts. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "LANSTON FONT | CASLON OLDSTYLE, 337 | WILLIAM CASLON". P22.com. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- "LTC Caslon Family". P22.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- "Microsoft Typography - News archive". Microsoft.com. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- "Audio". P22. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- "Why classic type is like a Victorian house". 7 August 2014. Retrieved 2022-11-11.

- "King's Caslon - Adobe Fonts". Retrieved 2022-11-11.

- Berkson, William. "Announcement on Typophile thread". Typophile. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Boston Pops: A Conversation with Patrick Mitchell". Archived from the original on 2009-10-14. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- Berkson, William. "Reviving Caslon, Part 1". Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Shaw, Paul (12 May 2011). "Flawed Typefaces". Print magazine. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Howes, Justin; Mosley, James; Chartres, Richard. "A to Z of Founder's London: A showing and synopsis of ITC Founder's Caslon" (PDF). Friends of the St. Bride's Printing Library. St Bride Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2005. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Download ITC Founder's Caslon™ font family". Linotype.com. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- "New Releases - Fonts.com". Itcfonts.com. 2012-10-16. Archived from the original on 2012-08-25. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- Howes, Justin. "Welcome to H. W. Caslon and Company Limited". H. W. Caslon and Company Limited (Archive image from 2004). Archived from the original on 20 September 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Howes, Justin (2003). "The Compleat Caslon". Matrix: 35–40.

- Howes, Justin. "Founders Caslon Text". H. W. Caslon and Company Limited (Archive image from 2004). Archived from the original on 20 September 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Howes, Justin. "Founders Caslon Display". H. W. Caslon and Company Limited (Archive image from 2004). Archived from the original on 13 October 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Howes, Justin. "Founders Caslon 1776". H. W. Caslon and Company Limited (Archive image from 2004). Archived from the original on 13 October 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "NotCaslon". Emigre. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- "Buy NotCaslon". Emigre. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- "NotCaslon". MyFonts. Emigre. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "P22 Franklin Caslon". MyFonts. P22. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

Early sources

- Rowe More, Dissertation 1778

- John Nicols, Biographical and Literary Anecdotes of William Bowyer 1782

- John Nicols, Literary Anecdotes, 1812–1815

The following two authors based their writings entirely on these three publications.

- Talbot Baines Reed, A History of Old English Letter Foundries, 1897

- Daniel Berkeley Updike, Printing types, their History, forms and use, 1937

Further reading

- Conseguera, David, Classic Typefaces: American Type and Type Designers, Skyhorse: 2011 ISBN 9781621535829.

- Lawson, Alexander S., Anatomy of a Typeface. Godine: 1990. ISBN 978-0-87923-333-4.

- Meggs, Phillip B, McKelvey, Roy. Revival of the Fittest: Digital Versions of Classic Typefaces. RC Publications, Inc.2000. ISBN 1-883915-08-2

- Updike, Daniel Berkeley. Printing Types: Their History, Forms, and Use. Dover Publications, Inc.: 1980. ISBN 0-486-23929-2

External links

- Fonts in Use (see sub-pages for use of specific versions)

Specimen books available online

- By the original Caslon Company, inherited by William Caslon II: Specimen of 1785 (issued by William Caslon III)

- By a breakaway company run by William Caslon III: Specimen of 1798 (completely different roman and italic typeface designs, in the transitional and modern style, although according to Reed most of the exotics are apparently obtained from the original Caslon foundry)

- H.W. Caslon & Co. Ltd., specimen book, 1915. The 20th century Caslon company at its height, including many sample settings.

- Late specimen sheet of the Caslon foundry from 1924: outside, inside. Included with Commercial Art magazine. George W. Jones's Caslon specimen of 1924 is similar.

- American Type Founders, 1912 Specimen Book. Includes Caslon samples on pages 116-123 & 314-353.

- American Type Founders, 1923 Specimen Book: complete digitisation, separate volumes (incomplete). Includes many examples of American releases of Caslon and sample settings in full-colour printing.

- 1953 article by Eugene Pattenburg in Print magazine on the popularity of Caslon in contemporary advertising. Many sample showings.