A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence, make findings of fact, and render an impartial verdict officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment. Most trial juries are "petit juries", and usually consist of twelve people. A larger jury known as a grand jury has been used to investigate potential crimes and render indictments against suspects.

The jury system developed in England during the Middle Ages and is a hallmark of the English common law system. Juries are commonly used in countries whose legal systems derive from the British Empire, such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and Ireland. They are not used in most other countries, whose legal systems are based upon European civil law or Islamic sharia law, although their use has been spreading.

Types of jury

The "petit jury" (or "trial jury", sometimes "petty jury") hears the evidence in a trial as presented by both the plaintiff (petitioner) and the defendant (respondent) (also known as the complainant and defendant within the English criminal legal system). After hearing the evidence and often jury instructions from the judge, the group retires for deliberation, to consider a verdict. The majority required for a verdict varies. In some cases it must be unanimous, while in other jurisdictions it may be a majority or supermajority. A jury that is unable to come to a verdict is referred to as a hung jury.

Grand jury

Main article: Grand juryA grand jury, a type of jury now confined mostly to federal courts and some state jurisdictions in the United States and Liberia, determines whether there is enough evidence for a criminal trial to go forward. Grand juries carry out this duty by examining evidence presented to them by a prosecutor and issuing indictments, or by investigating alleged crimes and issuing presentments. Grand juries are usually larger than trial juries: for example, U.S. federal grand juries have between 16 and 23 members. The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees Americans the constitutional right to be free from charges for "capital, or otherwise infamous" crimes unless they have been indicted by a grand jury, although this right applies only to federal law, not state law.

In addition to their primary role in screening criminal prosecutions and assisting in the investigation of crimes, grand juries in California, Florida, and some other U.S. states are sometimes utilized to perform an investigative and policy audit function similar to that filled by the Government Accountability Office in the United States federal government and legislative state auditors in many U.S. states.

In Ireland and other countries in the past, the task of a grand jury was to determine whether the prosecutors had presented a true bill (one that described a crime and gave a plausible reason for accusing the named person).

Coroner's jury

Main article: Coroner's juryAnother kind of jury, known as a coroner's jury can be convened in some common law jurisdiction in connection with an inquest by a coroner. A coroner is a public official (often an elected local government official in the United States), who is charged with determining the circumstances leading to a death in ambiguous or suspicious cases, such as of Jeffrey Epstein. A coroner's jury is generally a body that a coroner can convene on an optional basis in order to increase public confidence in the coroner's finding where there might otherwise be a controversy. In practice, coroner's juries are most often convened in order to avoid the appearance of impropriety by one governmental official in the criminal justice system toward another if no charges are filed against the person causing the death, when a governmental party such as a law enforcement officer is involved in the death.

Policy jury

This section is an excerpt from Citizens' assembly.

Citizens' assembly is a group of people selected by lottery from the general population to deliberate on important public questions so as to exert an influence. Other names and variations of deliberative mini-publics include citizens' jury, citizens' panel, people's panel, people's jury, policy jury, consensus conference and citizens' convention.

A citizens' assembly uses elements of a jury to create public policy. Its members form a representative cross-section of the public, and are provided with time, resources and a broad range of viewpoints to learn deeply about an issue. Through skilled facilitation, the assembly members weigh trade-offs and work to find common ground on a shared set of recommendations. Citizens' assemblies can be more representative and deliberative than public engagement, polls, legislatures or ballot initiatives. They seek quality of participation over quantity. They also have added advantages in issues where politicians have a conflict of interest, such as initiatives that will not show benefits before the next election or decisions that impact the types of income politicians can receive. They also are particularly well-suited to complex issues with trade-offs and values-driven dilemmas.

With Athenian democracy as the most famous government to use sortition, theorists and politicians have used citizens' assemblies and other forms of deliberative democracy in a variety of modern contexts. As of 2023, the OECD has found their use increasing since 2010.Historical roots

| The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with England and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (May 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The modern jury evolved out of the ancient custom of many ancient Germanic tribes whereby a group of men of certain social standing was used to investigate crimes and judge the accused. The same custom evolved into the vehmic court system in medieval Germany. In Anglo-Saxon England, juries investigated crimes. After the Norman Conquest, some parts of the country preserved juries as the means of investigating crimes. The use of ordinary members of the community to consider crimes was unusual in ancient cultures, but was nonetheless also found in ancient Greece.

The modern jury trial evolved out of this custom in the mid-12th century during the reign of Henry II. Juries, usually 6 or 12 men, were an "ancient institution" even then in some parts of England, at the same time as Members consisted of representatives of the basic units of local government—hundreds (an administrative sub-division of the shire, embracing several vills) and villages. Called juries of presentment, these men testified under oath to crimes committed in their neighbourhood. The Assize of Clarendon in 1166 caused these juries to be adopted systematically throughout the country. The jury in this period was "self-informing," meaning it heard very little evidence or testimony in court. Instead, jurors were recruited from the locality of the dispute and were expected to know the facts before coming to court. The source of juror knowledge could include first-hand knowledge, investigation, and less reliable sources such as rumour and hearsay.

Between 1166 and 1179 new procedures including a division of functions between the sheriff, the jury of local men, and the royal justices ushered in the era of the English Common Law. Sheriffs prepared cases for trial and found jurors with relevant knowledge and testimony. Jurors 'found' a verdict by witnessing as to fact, even assessing and applying information from their own and community memory—little was written at this time and what was, such as deeds and writs, were subject to fraud. Royal justices supervised trials, answered questions as to law, and announced the court's decision which was then subject to appeal. Sheriffs executed the decision of the court. These procedures enabled Henry II to delegate authority without endowing his subordinates with too much power.

In 1215 the Catholic Church removed its sanction from all forms of the ordeal—procedures by which suspects up to that time were 'tested' as to guilt (e.g., in the ordeal of hot metal, molten metal was sometimes poured into a suspected thief's hand. If the wound healed rapidly and well, it was believed God found the suspect innocent, and if not then the suspect was found guilty). With trial by ordeal banned, establishing guilt would have been problematic had England not had forty years of judicial experience. Justices were by then accustomed to asking jurors of presentment about points of fact in assessing indictments; it was a short step to ask jurors if they concluded the accused was guilty as charged.

The so-called Wantage Code provides an early reference to a jury-like group in England, wherein a decree issued by King Æthelred the Unready (at Wantage, c. 997) provided that in every Hundred "the twelve leading thegns together with the reeve shall go out and swear on the relics which are given into their hands, that they will not accuse any innocent man nor shield a guilty one." The resulting Wantage Code formally recognized legal customs that were part of the Danelaw.

The testimonial concept can also be traced to Normandy before 1066, when a jury of nobles was established to decide land disputes. In this manner, the Duke, being the largest land owner, could not act as a judge in his own case.

One of the earliest antecedents of modern jury systems is the jury in ancient Greece, including the city-state of Athens, where records of jury courts date back to 500 BCE. These juries voted by secret ballot and were eventually granted the power to annul unconstitutional laws, thus introducing the practice of judicial review. In modern justice systems, the law is considered "self-contained" and "distinct from other coercive forces, and perceived as separate from the political life of the community," but "all these barriers are absent in the context of classical Athens. In practice and in conception the law and its administration are in some important respects indistinguishable from the life of the community in general."

In juries of the Justices in Eyre, the bailiff of the hundred would choose 4 electors who in turn chose 12 others from their hundred, and from these were selected 12 jurors.

17th-18th century

From the 17th century until 1898 in Ireland, Grand Juries also functioned as local government authorities.

In 1730, the British Parliament passed the Bill for Better Regulation of Juries. The Act stipulated that the list of all those liable for jury service was to be posted in each parish and that jury panels would be selected by lot, also known as sortition, from these lists. Its aim was to prevent middle-class citizens from evading their responsibilities by financially putting into question the neutrality of the under-sheriff, the official entrusted with impaneling juries. Prior to the Act, the main means of ensuring impartiality was by allowing legal challenges to the sheriff's choices. The new provisions did not specifically aim at establishing impartiality but had the effect of reinforcing the authority of the jury by guaranteeing impartiality at the point of selection.

In some American colonies (such as in New England and Virginia) and less often in England, juries also handed down rulings on the law in addition to rulings on the facts of the case. The American grand jury was also indispensable to the American Revolution by challenging the Crown and Parliament, including by indicting British soldiers, refusing to indict people who criticized the crown, proposing boycotts and called for the support of the war after the Declaration of Independence.

In the late 18th century, English and colonial civil, criminal and grand juries played major roles in checking the power of the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.

19th century

In 1825, the rules concerning juror selection in England were consolidated. Property qualifications and various other rules were standardised, although an exemption was left open for towns which "possessed" their own courts. This reflected a more general understanding that local officials retained a large amount of discretion regarding which people they actually summoned. In the late eighteenth century, King has found evidence of butchers being excluded from service in Essex; while Crosby has found evidence of "peripatetic ice cream vendors" not being summoned in the summer time as late as 1923.

With the adoption of the Juries Act (Ireland) 1871, property qualifications for Irish jurors were partially standardized and lowered, so that jurors were drawn from among men who paid above a certain amount of taxes for poor relief. This expanded the number of potential jurors, even though only a small minority of Irish people were eligible to serve.

Until the 1870s, jurors in England and Ireland worked under the rule that they could not leave, eat, drink, or have a fire to warm themselves by, though they could take medicine. This rule appears to have been imposed with the idea that hungry jurors would be quicker to compromise, so they could reach a verdict and therefore eat. Jurors who broke the rule by smuggling in food were sometimes fined, and occasionally, especially if the food were believed to come from one of the parties in the case, the verdict was quashed. Later in the century, jurors who did not reach a verdict on the first day were no longer required to sleep in the courthouse, but were sometimes put up, at the expense of the parties in the trial, at a hotel.

20th century

After 1919 in England, women were no longer excluded from jury service by virtue of their sex, although they still had to satisfy the ordinary property qualifications. The exemption which had been created by the 1825 Act for towns which "possessed" their own courts meant ten towns were free to ignore the property qualifications. This amplified in these towns the general understanding that local officials had a free hand in summoning freely from among those people who were qualified to be jurors. In 1920, three of these ten towns – Leicester, Lincoln, and Nottingham – consistently empanelled assize juries of six men and six women; while at the Bristol, Exeter, and Norwich assizes no women were empanelled at all. This quickly led to a tightening up of the rules, and an abolition of these ten towns' discretion. After 1922, trial juries throughout England had to satisfy the same qualifications; although it was not until the 1980s that a centralised system was designed for selecting jurors from among the people who were qualified to serve. This meant there was still a great amount of discretion in the hands of local officials.

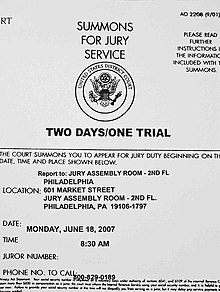

Summoning jurors

Potential jurors are summoned to the courthouse for service. In the past, jurors were identified manually, by local authorities making lists of men they believed to be eligible for service. In 19th-century Ireland, the list of eligible jurors in each court district was alphabetized, and in the later part of the century, the sheriff was required to summon one potential juror from each letter of the alphabet, repeating as needed until a sufficient number of men had been summoned, usually between 36 and 60 men for the quarterly assizes. Normally the sheriff or a constable went to each juror's home to show him the summons paperwork (venire facias de novo); it wasn't until 1871 that any Irish jurors could be summoned by mail. In modern times, juries are often initially chosen randomly, usually from large databases identifying the eligible population of adult citizens residing in the court's jurisdictional area (e.g., identity cards, drivers' licenses, tax records, or similar systems), and summons are delivered by mail.

In the past, qualifications included things like being an adult male, having a good reputation in the community, and owning land. Modern requirements may include being a citizen of that country and having a fluent understanding of the language used during the trial. In addition to a minimum age, some countries have a maximum age. Some countries disqualify people who have been previously convicted of a crime or excuse them on various grounds, such as being ill or holding certain jobs or offices.

Serving on a jury is normally compulsory for individuals who are qualified for jury service. Skipping service may be inevitable in a small number of cases, as a summoned juror might become ill or otherwise become unexpectedly unable to appear at the court. However, a significant fraction of summoned jurors may fail to appear for other reasons. In 1874, there was a report that one-third of summoned Irish jurors failed to appear in court.

When an insufficient number of summoned jurors appear in court to handle a matter, the law in many jurisdictions empowers the jury commissioner or other official convening the jury to involuntarily impress bystanders in the vicinity of the place where the jury is to be convened to serve on the jury.

Trial jury size

As the concept of a jury was spread through the British Empire, first to Ireland and then to other countries, the size of the jury was one of the details that was adapted to the local culture. The tradition in England was to have twelve jurors, but other countries use smaller juries, and some, such as Scotland, use larger juries.

The size of the jury is to provide a "cross-section" of the public. In Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970), the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that a Florida state jury of six was sufficient, that "the 12-man panel is not a necessary ingredient of "trial by jury," and that respondent's refusal to impanel more than the six members provided for by Florida law "did not violate petitioner's Sixth Amendment rights as applied to the States through the Fourteenth." In Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978), the Supreme Court ruled that the number of jurors could not be reduced below six.

In Brownlee v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 278, the High Court of Australia unanimously held that a jury of 12 members was not an essential feature of "trial by jury" in section 80 of the Australian Constitution.

In Scotland, a jury in a criminal trial consists of 15 jurors, which is thought to be the largest in the world. In 2009 a review by the Scottish Government regarding the possibility of reduction led to the decision to retain 15 jurors, with the Cabinet Secretary for Justice stating that after extensive consultation, he had decided that Scotland had got it "uniquely right". Trials in the Republic of Ireland which are scheduled to last over 2 months can, but do not have to, have 15 jurors.

A study by the University of Glasgow suggested that a civil jury of 12 people was ineffective because a few jurors ended up dominating the discussion, and that seven was a better number because more people feel comfortable speaking, and they have an easier time reaching a unanimous decision.

Jury selection

Main article: Jury selection

Jurors are expected to be neutral, so the court may inquire about the jurors' neutrality or otherwise exclude jurors who are perceived as likely to be less than neutral or partial to one side. Jury selection in the United States usually includes organized questioning of the prospective jurors (jury pool) by the lawyers for the plaintiff and the defendant and by the judge—voir dire—as well as rejecting some jurors because of bias or inability to properly serve ("challenge for cause"), and the discretionary right of each side to reject a specified number of jurors without having to prove a proper cause for the rejection ("peremptory challenge"), before the jury is impaneled.

Since there is always the possibility of jurors not completing a trial for health or other reasons, often one or more alternate jurors may be selected. Alternates are present for the entire trial but do not take part in deliberating the case and deciding the verdict unless one or more of the impaneled jurors are removed from the jury. For example, in the United Kingdom, a small number of alternate jurors may be empanelled until the end of the opening speeches by counsel, in case a juror realises they are familiar with the matters before the court.

Jurors are selected from a jury pool formed for a specified period of time—usually from one day to two weeks—from lists of citizens living in the jurisdiction of the court. The lists may be electoral rolls (i.e., a list of registered voters in the locale), people who have driver's licenses or other relevant data bases. When selected, being a member of a jury pool is, in principle, compulsory. Prospective jurors are sent a summons and are obligated to appear in a specified jury pool room on a specified date.

However, jurors can be released from the pool for several reasons including illness, prior commitments that cannot be abandoned without hardship, change of address to outside the court's jurisdiction, travel or employment outside the jurisdiction at the time of duty, and others. Often jurisdictions pay token amounts for jury duty and many issue stipends to cover transportation expenses for jurors. Work places cannot penalize employees who serve jury duty. Payments to jurors varies by jurisdiction.

In the United States jurors for grand juries are selected from jury pools.

Selection of jurors from a jury pool occurs when a trial is announced and juror names are randomly selected and called out by the jury pool clerk. Depending on the type of trial—whether a 6-person or 12 person jury is needed, in the United States—anywhere from 15 to 30 prospective jurors are sent to the courtroom to participate in voir dire, pronounced [vwaʁ diʁ] in French, the oath to speak the truth in the examination testing competence of a juror, or in another application, a witness. Once the list of prospective jurors has assembled in the courtroom the court clerk assigns them seats in the order their names were originally drawn. At this point the judge often will ask each prospective juror to answer a list of general questions such as name, occupation, education, family relationships, time conflicts for the anticipated length of the trial. The list is usually written up and clearly visible to assist nervous prospective jurors and may include several questions uniquely pertinent to the particular trial. These questions are to familiarize the judge and attorneys with the jurors and glean biases, experiences, or relationships that could jeopardize the proper course of the trial.

After each prospective juror has answered the general slate of questions the attorneys may ask follow-up questions of some or all prospective jurors. Each side in the trial is allotted a certain number of challenges to remove prospective jurors from consideration. Some challenges are issued during voir dire while others are presented to the judge at the end of voir dire. The judge calls out the names of the anonymously challenged prospective jurors and those return to the pool for consideration in other trials. A jury is formed, then, of the remaining prospective jurors in the order that their names were originally chosen. Any prospective jurors not thus impaneled return to the jury pool room.

Composition

A jury is intended to be an impartial panel capable of reaching a verdict and representing a variety of people from that area. Achieving this goal can be difficult when juror qualifications differ significantly from the people living in that area. For example, in 19th-century Ireland, the qualified jurors were much wealthier, much less likely to be Roman Catholic, and much less likely to speak only the Irish language than the typical Irish person. In the past, England had special juries, which empaneled only wealthier property owners as jurors. Attacks on the American jury increased after the pool of jurors expanded to include newly-enfranchised women and minorities.

A head juror is called the foreperson, foreman, or presiding juror. The foreperson may be chosen before the trial begins, or at the beginning of the jury's deliberations. The foreperson may be selected by the judge or by vote of the jurors, depending on the jurisdiction. The foreperson's role may include asking questions (usually to the judge) on behalf of the jury, facilitating jury discussions, and announcing the verdict of the jury.

Integrity

For juries to fulfill their role of analyzing the facts of the case, there are strict rules about their use of information during the trial. Juries are often instructed to avoid learning about the case from any source other than the trial (for example from media or the Internet) and not to conduct their own investigations (such as independently visiting a crime scene). Parties to the case, lawyers, and witnesses are not allowed to speak with a member of the jury. Doing these things may constitute reversible error. Rarely, such as in very high-profile cases, the court may order a jury sequestered for the deliberation phase or for the entire trial.

Jurors are generally required to keep their deliberations in strict confidence during the trial and deliberations, and in some jurisdictions even after a verdict is rendered. In Canadian and English law, the jury's deliberations must never be disclosed outside the jury, even years after the case; to repeat parts of the trial or verdict is considered to be contempt of court, a criminal offense. In the United States, confidentiality is usually only required until a verdict has been reached, and jurors have sometimes made remarks that called into question whether a verdict was properly reached. In Australia, academics are permitted to scrutinize the jury process only after obtaining a certificate or approval from the Attorney-General.

Because of the importance of preventing undue influence on a jury, embracery, jury intimidation or jury tampering (like witness tampering) is a serious crime, whether attempted through bribery, threat of violence, or other means. At various points in history, when threats to jurors became pervasive, the right to jury trial has been revoked, such as during the 1880s in Ireland.

Jurors themselves can also be held liable if they deliberately compromise their impartiality. Depending on local law, if a juror takes a bribe, the verdict may be overturned and the juror may be fined or imprisoned.

Robert Burns and Alexander Hamilton argued that jurors were the least likely decision-makers to be corrupted when compared to judges and all the political branches.

Role

The role of the jury is often described as that of a finder of fact, while the judge is usually seen as having the sole responsibility of interpreting the appropriate law and instructing the jury accordingly. The jury determines the truth or falsity of factual allegations and renders a verdict on whether a criminal defendant is guilty, or a civil defendant is civilly liable. Sometimes a jury makes specific findings of fact in what is called a "special verdict". A verdict without specific findings of fact that includes only findings of guilt, or civil liability and an overall amount of civil damages, if awarded, is called a "general verdict".

Juries are often justified because they leaven the law with community norms. A jury trial verdict in a case is binding only in that case, and is not a legally binding precedent in other cases. For example, it would be possible for one jury to find that particular conduct is negligent, and another jury to find that the conduct is not negligent, without either verdict being legally invalid, on precisely the same factual evidence. Of course, no two witnesses are exactly the same, and even the same witness will not express testimony in exactly the same way twice, so this would be difficult to prove. It is the role of the judge, not the jury, to determine what law applies to a particular set of facts. However, occasionally jurors find the law to be invalid or unfair, and on that basis acquit the defendant, regardless of the evidence presented that the defendant violated the law. This is commonly referred to as "jury nullification of law" or simply jury nullification. When there is no jury ("bench trial"), the judge makes rulings on both questions of law and of fact. In most continental European jurisdictions, judges have more power in a trial and the role and powers of a jury are often restricted. Actual jury law and trial procedures differ significantly between countries.

The collective knowledge and deliberate nature of juries are also given as reasons in their favor:

Detailed interviews with jurors after they rendered verdicts in trials involving complex expert testimony have demonstrated careful and critical analysis. The interviewed jurors clearly recognized that the experts were selected within an adversary process. They employed sensible techniques to evaluate the experts’ testimony, such as assessing the completeness and consistency of the testimony, comparing it with other evidence at the trial, and evaluating it against their own knowledge and life experience. Moreover, the research shows that in deliberations jurors combine their individual perspectives on the evidence and debate its relative merits before arriving at a verdict.

In the United States, juries are sometimes called on, when asked to do so by a judge in the jury instructions, to make factual findings on particular issues. This may include, for example, aggravating circumstances which will be used to elevate the defendant's sentence if the defendant is convicted. This practice was required in all death penalty cases in Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 (2004), where the Supreme Court ruled that allowing judges to make such findings unilaterally violates the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial. A similar Sixth Amendment argument in Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000) resulted in the Supreme Court's expansion of the requirement to all criminal cases, holding that "any fact that increases the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum must be submitted to a jury and proved beyond a reasonable doubt".

Many U.S. jurisdictions permit the seating of an advisory jury in a civil case in which there is no right to trial by jury to provide non-binding advice to the trial judge, although this procedural tool is rarely used. For example, a judge might seat an advisory jury to guide the judge in awarding non-economic damages (such as "pain and suffering" damages) in a case where there is no right to a jury trial, such as (depending on state law) a case involving "equitable" rather than "legal" claims.

In Canada, juries are also allowed to make suggestions for sentencing periods at the time of sentencing. The suggestions of the jury are presented before the judge by the Crown prosecutor(s) before the sentence is handed down. In a small number of U.S. jurisdictions, including the states of Tennessee and Texas, juries are charged both with the task of finding guilt or innocence as well assessing and fixing sentences.

However, this is not the practice in most other legal systems based on the English tradition, in which judges retain sole responsibility for deciding sentences according to law. The exception is the award of damages in English law libel cases, although a judge is now obliged to make a recommendation to the jury as to the appropriate amount.

In legal systems based on English tradition, findings of fact by a jury, and jury conclusions that could be supported by jury findings of fact even if the specific factual basis for the verdict is not known, are entitled to great deference on appeal. In other legal systems, it is generally possible for an appellate court to reconsider both findings of fact and conclusions of law made in the trial court, and in those systems, evidence may be presented to appellate courts in what amounts to a trial de novo (new trial) of appealed findings of fact. The finality of trial court findings of fact in legal systems based on the English tradition has a major impact on court procedure in these systems. This makes it imperative that lawyers be highly prepared for trial because errors and misjudgments related to the presentation of evidence at trial to a jury cannot generally be corrected later on appeal, particularly in court systems based on the English tradition. The higher the stakes, the more this is true. Surprises at trial are much more consequential in court systems based on the English tradition than they are in other legal systems.

Scholarly research on jury behavior in American non-capital criminal felony trials reveals that juror outcomes appear to track the opinions of the median juror, rather than the opinions of the extreme juror on the panel, although juries were required to render unanimous verdicts in the jurisdictions studied. Thus, although juries must render unanimous verdicts, in run-of-the-mill criminal trials they behave in practice as if they were operating using a majority rules voting system.

Jury nullification

Main article: Jury nullificationJury nullification means deciding not to apply the law to the facts in a particular case by jury decision. In other words, it is "the process whereby a jury in a criminal case effectively nullifies a law by acquitting a defendant regardless of the weight of evidence against him or her."

In the 17th and 18th centuries, there was a series of such cases, starting in 1670 with the trial of the Quaker William Penn which asserted the (de facto) right, or at least power, of a jury to render a verdict contrary to the facts or law. A good example is the case of one Carnegie of Finhaven who in 1728 accidentally killed the Scottish Earl of Strathmore. As the defendant had undoubtedly killed the Earl, the law (as it stood) required the jury to render the verdict that the case had been "proven" and cause Carnegie of Finhaven to die for an accidental killing. Instead, the jury asserted what is believed to be their "ancient right" to judge the whole case and not just the facts and brought in the verdict of "not guilty".

Today in the United States, juries are instructed by the judge to follow the judge's instructions concerning what is the law and to render a verdict solely on the evidence presented in court. Important past exercises of nullification include cases involving slavery (see Fugitive Slave Act of 1850), freedom of the press (see John Peter Zenger), and freedom of religion (see William Penn).

In United States v. Moylan, 417 F.2d 1002 (4th. Cir. 1969), Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal unanimously ruled: "If the jury feels that the law under which the defendant is accused is unjust, or exigent circumstances justified the actions of the accused, or for any reason which appeals to their logic or passion, the jury has the right to acquit, and the courts must abide that decision." The Fully Informed Jury Association is a non-profit educational organization dedicated to informing jurors of their rights and seeking the passage of laws to require judges to inform jurors that they can and should judge the law. In Sparf v. United States, 156 U.S. 51 (1895), the Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision, held that a trial judge has no responsibility to inform the jury of the right to nullify laws.

Modern American jurisprudence is generally intolerant of the practice, and a juror can be removed from a case if the judge believes that the juror is aware of the power of nullification.

Jury equity

In the United Kingdom, a similar power exists, often called jury equity. This enables a jury to reach a decision in direct contradiction with the law if they feel the law is unjust. This can create a persuasive precedent for future cases, or render prosecutors reluctant to bring a charge – thus a jury has the power to influence the law.

The standard justification of jury equity is taken from the final few pages of Lord Devlin's book Trial by Jury. Devlin explained jury equity through two now-famous metaphors: that the jury is "the lamp that shows that freedom lives" and that it is a "little parliament". The second metaphor emphasises that, just as members of parliament are generally dominated by government but can occasionally assert their independence, juries are usually dominated by judges but can, in extraordinary circumstances, throw off this control. Devlin thereby sought to emphasise that neither jury equity nor judicial control is set in stone.

Perhaps the best example of modern-day jury equity in England and Wales was the acquittal of Clive Ponting, on a charge of revealing secret information, under section 2 of the Official Secrets Act 1911 in 1985. Mr Ponting's defence was that the revelation was in the public interest. The trial judge directed the jury that "the public interest is what the government of the day says it is" – effectively a direction to the jury to convict. Nevertheless, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty.

Another example is the acquittal in 1989 of Michael Randle and Pat Pottle, who confessed in open court to charges of springing the Soviet spy George Blake from Wormwood Scrubs Prison and smuggling him to East Germany in 1966. Pottle successfully appealed to the jury to disregard the judge's instruction that they consider only whether the defendants were guilty in law, and assert a jury's ancient right to throw out a politically motivated prosecution, in this case, compounded by its cynical untimeliness.

In Scotland (with a separate legal system from that of England and Wales) although technically the "not guilty" verdict was originally a form of jury nullification, over time the interpretation has changed so that now the "not guilty" verdict has become the normal one when a jury is not persuaded of guilt and the "not proven" verdict is only used when the jury is not certain of innocence or guilt. It is absolutely central to Scottish and English law that there is a presumption of innocence. It is not a trivial distinction, since any shift in the burden of proof is a significant change which undermines the safeguard for the citizen.

Jury sentencing

See also: Juries in the United States § Jury-imposed sentencesJury sentencing is the practice of having juries decide what penalties to give those who have been convicted of criminal offenses. The practice of jury sentencing began in the US state of Virginia in the 18th century and spread westward to other states that were influenced by Virginia-trained lawyers.

Canadian juries have long had the option to recommend mercy, leniency, or clemency, and the 1961 Criminal Code required judges to give a jury instruction, following a verdict convicting a defendant of capital murder, soliciting a recommendation as to whether he should be granted clemency. When capital punishment in Canada was abolished in 1976, as part of the same raft of reforms, the Criminal Code was also amended to grant juries the ability to recommend periods of parole ineligibility immediately following a guilty verdict in second-degree murder cases; however, these recommendations are usually ignored, based on the idea that judges are better-informed about relevant facts and sentencing jurisprudence and, unlike the jury, permitted to give reasons for their judgments.

Proponents of jury sentencing argue that since sentencing involves fact-finding (a task traditionally within the purview of juries), and since the original intent of the founders was to have juries check judges' power, it is the proper role of juries to participate in sentencing. Opponents argue that judges' training and experience with the use of presentence reports and sentencing guidelines, as well as the fact that jury control procedures typically deprive juries of the opportunity to hear information about the defendant's background during the trial, make it more practical to have judges sentence defendants. In Canada, a faint hope clause formerly allowed a jury to be empanelled to consider whether an offender's number of years of imprisonment without eligibility for parole ought to be reduced, but this was repealed in 2011.

Sentencing is said to be more time-consuming for jurors than the relatively easy task of ascertaining guilt or innocence, which means an increase in jury fees and in the amount of productivity lost to jury duty. In New South Wales, a 2007 proposal by Chief Justice Jim Spigelman to involve juries in sentencing was rejected after District Court Chief Judge Reg Blanch cited "an expected wide difference of views between jurors about questions relating to sentence". Concerns about jury tampering through intimidation by defendants were also raised.

Germany and many other continental European countries have a system in which professional judges and lay judges deliberate together at both the trial and sentencing stages; such systems have been praised as a superior alternative because the mixed court dispenses with most of the time‐consuming practices of jury control that characterize Anglo‐American trial procedure, yet serves the purposes of a jury trial better than plea bargaining and bench trials, which have displaced the jury from routine American practice.

Experience of jurors

The experience of individual jurors is understudied. However, during times of political unrest jurors have been criminally threatened or physically harmed because of their service, and this resulted in people being less willing to serve, or to prefer the risk of judicial fines for not serving to the risk of criminal retribution if they do serve on the jury.

Jurors typically take their roles very seriously. According to Simon (1980), jurors approach their responsibilities as decision makers much in the same way as a court judge: with great seriousness, a lawful mind, and a concern for consistency that is evidence-based. By actively processing evidence, making inferences, using common sense and personal experiences to inform their decision-making, research has indicated that jurors are effective decision makers who seek thorough understanding, rather than passive, apathetic participants unfit to serve on a jury.

Jury effectiveness

Contemporary research has provided partial support for the proficiency of juries as decision makers due to taking their work seriously to get a fair outcome and by relying on the group to overcome individual biases. Some note the imperfections in the process and advocate for amendments to the system, with only 3% of US judges favoring abolishing the jury. The thoroughness of the jury trial has also been praised for providing the public with important information that is often not released in alternative procedures like arbitration or adjudication by judges or administrative agencies.

Judge-jury agreement

Evidence supporting jury effectiveness has also been illustrated in studies that investigate the parallels between judge and jury decision-making. According to Kalven and Zeisel (1966), it is not uncommon to find that the verdicts passed down by juries following a trial match the verdicts held by the appointed judges. Upon surveying judges and jurors of approximately 8,000 criminal and civil trials, it was discovered that the verdicts handed down by both parties were in agreement 80% of the time.

Suja A. Thomas argues that, "although results between judges and juries may be similar, judges and juries can disagree. If a choice must be made between a judge or a jury deciding, the diversity, availability of deliberations, the requirement for consensus, the lack of monetary or promotion incentives, and the fresh examination of evidence all make the jury the most attractive, least-biased decision-maker."

Buffering effects

Jurors, like most individuals, are not free from holding social and cognitive biases, which could result in sentencing disparities. People may negatively judge individuals who do not adhere to established social norms (e.g., an individual's dress sense) or do not meet societal standards of success. Although these biases tend to influence jurors' individual decisions during a trial, while working as part of a group (i.e., jury), these biases are typically controlled. Groups tend to exert buffering effects that allow jurors to disregard their initial personal biases when forming a credible group decision. Analysis of over a quarter million felony cases in USA found for grand juries no statistical significance for taste-based or statistical discrimination between black and white defendants.

Robert Burns cites Plato in arguing that gaining power and ruling wisely are different skillsets, making the case for a jury of those who have not sought power to create better outcomes than trials left up to judges. Burns further argues that interest groups have increasing influence over political branches, including judges, and that the jury was designed to resist the new Gilded Age-level concentration of power. He also cites Blackstone who argued that it was against human nature for the few (judges) to be attentive to the needs of the many. He also argues the legitimacy of the judiciary increases with a more robust jury. The trial also provides the public with insight into the conduct of judges and the parties involved, further encouraging good behavior. Unlike in other major institutions that run on a more bureaucratic utilitarian logic, the jury checks this way of thinking by bringing common-sense and moral perspectives to bear. Burns contrasts the focus on fact for a jury with other political processes like congressional forums, which he argues are undisciplined forums for overbroad abstractions. Lastly, Burns argues the jury is a vote of confidence for democracy as the most democratic institution (at least in America) and one that demonstrates that it is possible to find common ground on difficult questions, especially when decisions must be unanimous.

Trial procedures by country

See also: Jury trial § In various countriesOverall, jury use has been increasing worldwide.

Africa

Ghana

In Ghana, juries have seven members, and their sole duty is to determine whether the person is guilty. They have no role in sentencing.

Americas

Brazil

The Constitution of Brazil provides that only willful crimes against life, namely full or attempted murder, abortion, infanticide and suicide instigation, be judged by juries. Seven jurors vote in secret to decide whether the defendant is guilty or not, and decisions are taken by the majority.

Manslaughter and other crimes in which the killing was committed without intent, however, are judged by a professional judge instead.

Canada

In Canada, juries are used for some criminal trials but not others. For summary conviction offences or offences found under section 553 of the Criminal Code (theft and fraud up to the value of $5,000 and certain nuisance offences), the trial is before a judge alone. For most indictable offences, the accused person can elect to be tried by either a judge alone or a judge and jury. In the most serious offences, found in section 469 of the Criminal Code (such as murder or treason), a judge and a jury are always used, unless both the accused and the prosecutor agree that the trial should not be in front of a jury. The jury's verdict on the ultimate disposition of guilt or innocence must be unanimous, but can disagree on the evidentiary route that leads to that disposition.

Juries do not make a recommendation as to the length of sentence, except for parole ineligibility for second-degree murder (but the judge is not bound by the jury's recommendation, and the jury is not required to make a recommendation).

Jury selection is in accordance with specific criteria. Prospective jurors may only be asked certain questions, selected for direct pertinence to impartiality or other relevant matters. Any other questions must be approved by the judge.

A jury in a criminal trial initially has 12 members. The trial judge has the discretion to direct that one or two alternate jurors also be appointed. If a juror is discharged during the course of the trial, the trial will continue with an alternate juror, unless the number of jurors goes below 10.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees that anyone tried for an offense that has a maximum sentence of five or more years has the right to be tried by a jury (except for an offence under military law).

The names of jurors are protected by a publication ban. There is a specific criminal offense for disclosing anything that takes place during jury deliberations.

Juries are infrequently used in civil trials in Canada. There are no civil juries in the courts of the province of Quebec, nor in the Federal Court.

United States

Main article: Juries in the United StatesIn criminal law in federal courts and a minority of state court systems of the United States, a grand jury is convened to hear only testimony and evidence to determine whether there is a sufficient basis for deciding to indict the defendant and proceed toward trial. In each court district where a grand jury is required, a group of 16–23 citizens holds an inquiry on criminal complaints brought by the prosecutor to decide whether a trial is warranted (based on the standard that probable cause exists that a crime was committed), in which case an indictment is issued. In jurisdictions where the size of a jury varies, in general the size of juries tends to be larger if the crime alleged is more serious. If a grand jury rejects a proposed indictment the grand jury's action is known as a "no bill." If they accept a proposed indictment, the grand jury's action is known as a "true bill." Grand jury proceedings are ex parte: only the prosecutor and witnesses who the prosecutor calls may present evidence to the grand jury and defendants are not allowed to present mitigating evidence or even to know the testimony that was presented to the grand jury, and hearsay evidence is permitted. This is so because a grand jury cannot convict a defendant. It can only decide to indict the defendant and proceed forward toward trial. Grand juries vote to indict in the overwhelming majority of cases, and prosecutors are not prohibited from presenting the same case to a new grand jury if a "no bill" was returned by a previous grand jury. A typical grand jury considers a new criminal case every fifteen minutes. In some jurisdictions, in addition to indicting persons for crimes, a grand jury may also issue reports on matters that they investigate apart from the criminal indictments, particularly when the grand jury investigation involves a public scandal. Historically, grand juries were sometimes used in American law to serve a purpose similar to an investigatory commission.

Both Article III of the U.S. Constitution and the Sixth Amendment require that criminal cases be tried by a jury. Originally this applied only to federal courts. However, the Fourteenth Amendment extended this mandate to the states. Although the Constitution originally did not require a jury for civil cases, this led to an uproar which was followed by adoption of the Seventh Amendment, which requires a civil jury in cases where the value in dispute is greater than twenty dollars. However, the Seventh Amendment right to a civil jury trial does not apply in state courts, where the right to a jury is strictly a matter of state law. However, in practice, all states except Louisiana preserve the right to a jury trial in almost all civil cases where the sole remedy sought is money damages to the same extent as jury trials are permitted by the Seventh Amendment. Under the law of many states, jury trials are not allowed in small claims cases. The civil jury in the United States is a defining element of the process by which personal injury trials are handled.

In practice, even though the defendant in a criminal action is entitled to a trial by jury, most criminal actions in the U.S. are resolved by plea bargain. Only about 2% of civil cases go to trial, with only about half of those trials being conducted before juries.

In 1898 the Supreme Court held that the jury must be composed of at least twelve persons, although this was not necessarily extended to state civil jury trials. In 1970, however, the Supreme Court held that the twelve person requirement was a "historical accident", and upheld six-person juries if provided for under state law in both criminal and civil state court cases. There is controversy over smaller juries, with proponents arguing that they are more efficient and opponents arguing that they lead to fluctuating verdicts. In a later case, however, the court rejected the use of five-person juries in criminal cases. Juries go through a selection process called voir dire in which the lawyers question the jurors and then make "challenges for cause" and "peremptory challenges" to remove jurors. Traditionally the removal of jurors based on a peremptory challenge required no justification or explanation, but the tradition has been changed by the Supreme Court where the reason for the peremptory challenge was the race of the potential juror. Since the 1970s "scientific jury selection" has become popular.

Unanimous jury verdicts have been standard in US American law. This requirement was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1897, but the standard was relaxed in 1972 in two criminal cases. As of 1999 over thirty states had laws allowing less than unanimity in civil cases, but, until 2020, Oregon and Louisiana were the only states which have laws allowing less than unanimous jury verdicts for criminal cases (these laws were overturned in Ramos v. Louisiana). When the required number of jurors cannot agree on a verdict (a situation sometimes referred to as a hung jury), a mistrial is declared, and the case may be retried with a newly constituted jury. The practice generally was that the jury rules only on questions of fact and guilt; setting the penalty was reserved for the judge. This practice was confirmed by rulings of the U.S. Supreme Court such as in Ring v. Arizona, which found Arizona's practice of having the judge decide whether aggravating factors exist to make a defendant eligible for the death penalty, to be unconstitutional, and reserving the determination of whether the aggravating factors exist to be decided by the jury. However, in some states (such as Alabama and Florida), the ultimate decision on the punishment is made by the judge, and the jury gives only a non-binding recommendation. The judge can impose the death penalty even if the jury recommends life without parole.

There is no set format for jury deliberations, and the jury takes a period of time to settle into discussing the evidence and deciding on guilt and any other facts the judge instructs them to determine. Deliberation is done by the jury only, with none of the lawyers, the judge, or the defendant present. The first step will typically be to find out the initial feeling or reaction of the jurors to the case, which may be by a show of hands, or via secret ballot. The jury will then attempt to arrive at a consensus verdict. The discussion usually helps to identify jurors' views to see whether a consensus will emerge as well as areas that bear further discussion. Points often arise that were not specifically discussed during the trial. The result of these discussions is that in most cases the jury comes to a unanimous decision and a verdict is thus achieved. In some states and under circumstances, the decision need not be unanimous.

In a few states and in death penalty cases, depending upon the law, the trial jury, or sometimes a separate jury, may determine whether the death penalty is appropriate in "capital" murder cases. Usually, sentencing is handled by the judge at a separate hearing. The judge may but does not always follow the recommendations of the jury when deciding on a sentence.

Asia and Oceania

Australia

States

Each state may determine the extent to which the use of a jury is used. The use of a jury is optional for civil trials in any Australian state. The use of a jury in criminal trials is generally by a unanimous verdict of 12 lay members of the public. Some States provide exceptions such as majority (11-to-1 or 10-to-2) verdicts where a jury cannot otherwise reach a verdict. All states except Victoria allow a person accused of a criminal offence to elect to be tried by a judge-alone rather than the default jury provision.

Commonwealth (Federal)

The Constitution of Australia provides in section 80 that 'the trial on indictment of any offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be by jury'. The Commonwealth can determine which offences are 'on indictment'. It would be entirely consistent with the Constitution that a homicide offence could be tried not 'on indictment,' or conversely that a simple assault could be tried 'on indictment.' This interpretation has been criticized as a 'mockery' of the section, rendering it useless.

Where a trial 'on indictment' has been prescribed, it is an essential element that it be found by a unanimous verdict of guilty by 12 lay members of the public. This requirement stems from the (historical) meaning of 'jury' at the time that the Constitution was written and is (in principle) thus an integral element of trial by jury. Unlike in the Australian states, an accused person cannot elect a Judge-only trial, even where both the accused and the prosecutor seek such a trial.

In November 2023, Indigenous Australian law expert Pattie Lees called for greater inclusion of First Nations people in the jury system to create a more "fair, just" system."

Hong Kong

Main article: Jury system in Hong KongArticle 86 of the Hong Kong Basic Law assures the practice of jury trials. Criminal cases in the High Court and some civil cases are tried by a jury in Hong Kong. There is no jury in the District Court. In addition, from time to time, the Coroner's Court may summon a jury to decide the cause of death in an inquest. Criminal cases are normally tried by a 7-person jury and sometimes, at the discretion of the court, a 9-person jury. Nevertheless, the Jury Ordinance requires that a jury in any proceedings should be composed of at least 5 jurors.

Although article 86 of the basic law states that ‘the principle of trial by jury previously practiced in Hong Kong shall be maintained’, it does not guarantee that every case is to be tried by a jury. In the case Chiang Lily v. Secretary for Justice (2010), the Court of Final Appeal agreed that ‘there is no right to trial by jury in Hong Kong.’

India

Jury trials were abolished in most Indian courts by the 1973 Code of Criminal Procedure . Nanavati Case was not the last Jury trial in India. West Bengal had Jury trials as late as 1973. Juries were not mentioned in the 1950 Indian Constitution, and it was ignored in many Indian states. The Law Commission recommended their abolition in 1958 in its 14th Report. They were retained in a discreet manner for Parsi divorce courts, wherein a panel of members called 'delegates' are randomly selected from the community to decide the fact of the case. Parsi divorce law is governed by 'The Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936' as amended in 1988, and is a mixture of the Panchayat legal system and jury process.

New Zealand

Juries are used in all trials involving Category 4 offences such as treason, murder and manslaughter, although in exceptional circumstances a judge-alone trial may be ordered. At the option of the defendant, juries may be used in trials involving Category 3 offences, that is, offences where the maximum penalty available is two years' imprisonment or greater. In civil cases, juries are only used in cases of defamation, false imprisonment and malicious prosecution. Juries must initially try to reach a unanimous verdict, but if one cannot be reached in a reasonable timeframe, the judge may accept a majority verdict of all-but-one (i.e. 11–1 or 10–1) in criminal cases and three-quarters (i.e. 9–3 or 9–2) in civil cases.

Europe

Belgium

The Belgian Constitution provides that all cases involving the most serious crimes be judged by juries. As a safeguard against libel cases, press crimes can also only be tried by a jury. Racism is excluded from this safeguard.

Twelve jurors decide by a qualified majority of two-thirds whether the defendant is guilty or not. A tied vote result in 'not guilty'; a '7 guilty – 5 not guilty' vote is transferred to the 3 professional judges who can, by unanimity, reverse the majority to 'not guilty'. The sentence is delivered by a majority of the 12 jurors and the 3 professional judges. As a result of the Taxquet ruling the juries give nowadays the most important motives that lead them to their verdict. The procedural codification has been altered to meet the demands formulated by the European Court of Human Rights.

France

In the Cour d'assises

Three professional judges sit alongside six jurors in first instance proceedings or nine in appeal proceedings. Before 2012, there were nine or twelve jurors, but this was reduced to cut spending. A two-thirds majority is needed in order to convict the defendant. During these procedures, judges and jurors have equal positions on questions of fact, while judges decide on questions of procedure. Judges and jurors also have equal positions on sentencing.

Germany

Trial by jury was introduced in most German states after the revolutionary events of 1848. However, it remained controversial; and, early in the 20th century, there were moves to abolish it. The Emminger Reform of January 4, 1924, during an Article 48 state of emergency, abolished the jury system and replaced it with a mixed system including bench trials and lay judges.

In 1925, the Social Democrats called for the reinstitution of the jury; a special meeting of the German Bar demanded revocation of the decrees, but "on the whole the abolition of the jury caused little commotion". Their verdicts were widely perceived as unjust and inconsistent.

Today, most misdemeanors are tried by a Strafrichter, meaning a single judge at an Amtsgericht; felonies and more severe misdemeanors are tried by a Schöffengericht, also located at the Amtsgericht, composed of 1 judge and 2 lay judges; some felonies are heard by Erweitertes Schöffengericht, or extended Schöffengericht, composed of 2 judges and 2 lay judges; severe felonies and other "special" crimes are tried by the große Strafkammer, composed of 3 judges and 2 lay judges at the Landgericht, with specially assigned courts for some crimes called Sonderstrafkammer; felonies resulting in the death of a human being are tried by the Schwurgericht, composed of 3 judges and 2 lay judges, located at the Landgericht; and serious crimes against the state are tried by the Strafsenat, composed of 5 judges, at an Oberlandesgericht.

In some civil cases, such as commercial law or patent law, there are also lay judges, who have to meet certain criteria (e.g., being a merchant).

Ireland

The law in Ireland is historically based on English common law and had a similar jury system. Article 38 of the 1937 Constitution of Ireland mandates trial by jury for criminal offences, with exceptions for minor offences, military tribunals, and where "the ordinary courts are inadequate to secure the effective administration of justice, and the preservation of public peace and order". In DPP v Nally IECCA 128 Kearns J set out that a jury has the right to reach a not guilty verdict even in direct contradiction of the evidence.

The principal statute regulating the selection, obligations and conduct of juries is the Juries Act 1976 as amended by the Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2008. There is a fine of €500 for failing to report for jury service, though this was poorly enforced until a change of policy at the Courts Service in 2016. Criminal jury trials are held in the Circuit Court or the Central Criminal Court. Juryless trials under the inadequacy exception, dealing with terrorism or organised crime, are held in the Special Criminal Court, on application by the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). Juries are also used in some civil law trials, such as for defamation; they are sometimes used at coroner's inquests.

Normally consisting of twelve persons, juries are selected from a jury panel which is picked at random by the county registrar from the electoral register. Juries only decide questions of fact and have no role in criminal sentencing. It is not necessary that a jury be unanimous in its verdict. In civil cases, a verdict may be reached by a majority of nine of the twelve members. In a criminal case, a verdict need not be unanimous where there are not fewer than eleven jurors if ten of them agree on a verdict after considering the case for a "reasonable time". Juries are not paid, nor do they receive travel expenses; however they do receive lunch for the days that they are serving. The Law Reform Commission examined jury service, producing a consultation paper in 2010 and then a report in 2013. One of its recommendations, to permit extra jurors for long trials in case some are excused, was enacted in 2013. In November 2013, the DPP requested a 15-member jury at the trial of three Anglo Irish Bank executives. Where more than twelve jurors are present, twelve will be chosen by lot to retire and consider the verdict.

Italy

In Italy, a civil law jurisdiction, untrained judges are present only in the Corte d'Assise, where two career magistrates are supported by six so-called lay judges, who are chosen by lot from the registrar of voters. Any Italian citizen, with no distinction of sex or religion, between 30 and 65 years of age, can be appointed as a lay judge; in order to be eligible as a lay judge for the Corte d'Assise, however, there is a minimum educational requirement, as the lay judge must have completed his/her education at the Scuola Media (junior high school) level, while said level is raised for the Corte d'Assise d'Appello (appeal level of the Corte d'Assise) to the Scuola Superiore (senior high school) degree. In the Corte d'Assise, decisions concerning both fact and law matters are taken by the stipendiary judges and "lay judges" together at a special meeting behind closed doors, named Camera di Consiglio ("Counsel Chamber"), and the Court is subsequently required to publish written explanations of its decisions within 90 days from the verdict. Errors of law or inconsistencies in the explanation of a decision can and usually will lead to the annulment of the decision. A Court d'Assise and a Court d'Assise d'Appello decides on a majority of votes, and therefore predominantly on the votes of the lay judges, who are a majority of six to two, but in fact lay judges, who are not trained to write such explanation and must rely on one or the other stipendiary judge to do it, are effectively prevented from overruling both of them. The Corte d'Assise has jurisdiction to try crimes carrying a maximum penalty of 24 years in prison or life imprisonment, and other serious crimes; felonies that fall under its jurisdiction include terrorism, murder, manslaughter, severe attempts against State personalities, as well as some matters of law requiring ethical and professional evaluations (e.g. assisted suicide), while it generally has no jurisdiction over cases whose evaluation requires knowledge of law which the "lay judges" generally do not have. Penalties imposed by the court can include life sentences.

Norway

Juries existed in Norway as early as the year 800, and perhaps even earlier. They brought the jury system to England and Scotland. Juries were phased out as late as the 17th century, when Norway's central government was in Copenhagen, Denmark. Though Norway and Denmark had different legal systems throughout their personal union (1387–1536), and later under the governmental union (1536–1814), there was attempt to harmonize the legal systems of the two countries. Even if juries were abolished, the layman continued to play an important role in the legal system throughout in Norway.

The jury was reintroduced in 1887, and was then solely used in criminal cases on the second tier of the three-tier Norwegian court system ("Lagmannsretten"). The jury consisted of 10 people, and had to reach a majority verdict consisting of seven or more of the jurors. The jury never gave a reason for its verdict, rather it simply gave a "guilty" or "non-guilty" verdict. The jury foreperson, elected by the jury on the first day, with three other jury members also made up the majority in the sentencing, if the accused were found guilty.

In Norway the term "guilty", is not used, only yes or no to the actions asked them to consider done by the accused by the prosecutor. The last jury case was in 2018, after juries were abolished after the European Court condideres that no-one should be sentenced without the considerations in the judgement.

In a sense, the concept of being judged by one's peers existed on both the first and second tier of the Norwegian court system: In Tingretten, one judge and two lay judges preside, and in Lagmannsretten two judges and five lay judges preside. The lay judges do not hold any legal qualification, and represent the peers of the person on trial, as members of the general public. As a guarantee against any abuse of power by the educated elite, the number of lay judges always exceeds the number of appointed judges. In the Supreme Court, only trained lawyers are seated.

Russia

The right to a jury trial is provided by Constitution of Russian Federation but for criminal cases only and in the procedure defined by law. Initially, the Criminal Procedure Code, which was adopted in 2001, provided that the right to a jury trial could be realized in criminal cases which should be heard by regional courts and military courts of military districts/fleets as the courts of first instance; the jury was composed of 12 jurors. In 2008, the anti-state criminal cases (treason, espionage, armed rebellion, sabotage, mass riot, creating an illegal paramilitary group, forcible seizure of power, terrorism) were removed from the jurisdiction of the jury trial. From 1 June 2018, defendants can claim a jury trial in criminal cases which are heard by district courts and garrison military courts as the courts of first instance; from that moment on, the jury is composed of 8 (in regional courts and military courts of military districts/fleets) or 6 (in district courts and garrison military courts) jurors.

A juror must be 25 years old, legally competent, and without a criminal record.

Spain

Spain has no strong tradition of using juries. However, there is some mentions in the Bayonne Statute of 1808. Later, Article 307 of the Spanish Constitution of 1812 allowed the Cortes to pass legislation if they felt that over the time it was needed to distinguish between "judges of law" and "judges of facts". Such legislation however was never enacted.

Article 2 of the Spanish Constitution of 1837 while proclamating the freedom of the people to publicate written contents without previous censorship according to the laws also provided that "press crimes" could only be tried by juries. This meant that a grand jury would need to indict, and a petit jury would need to convict.

Juries were later abolished in 1845, but were later restored in 1869 for all "political crimes" and "those common crimes the law may deem appropriate to be so tried by a jury". A Law concerning the Jury entered into force on January 1, 1899, and lasted until 1936, where juries were again disbanded with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

The actual Constitution of 1978 permits the Cortes Generales to pass legislation allowing juries in criminal trials. The provision is arguably somewhat vague: "Article 125 – Citizens may engage in popular action and participate in the administration of justice through the institution of the Jury, in the manner and with respect to those criminal trials as may be determined by law, as well as in customary and traditional courts."

Jury trials can only happen in the criminal jurisdiction and it is not a choice of the defendant to be tried by jury, or by a single judge or a panel of judges. Organic Law 5/1995, of May 22 regulates the categories of crimes in which a trial by jury is mandatory. For all other crimes, a single judge or a panel of judges will decide both on facts and the law. Spanish juries are composed of 9 citizens and a professional Judge. Juries decide on facts and whether to convict or acquit the defendant. In case of conviction they can also make recommendations such as if the defendant should be pardoned if they asked to, or if they think the defendant could be released on parole, etc.

One of the first jury trial cases was that of Mikel Otegi who was tried in 1997 for the murder of two police officers. After a confused trial, five jury members of a total of nine voted to acquit and the judge ordered the accused set free. This verdict shocked the nation. An alleged miscarriage of justice by jury trial was the Wanninkhof murder case.

Sweden

Further information: Judiciary of Sweden § JuriesIn press libel cases and other cases concerning offenses against freedom of the press, the question of whether or not the printed material falls outside permissible limits is submitted to a jury of 9 members which provides a pre-screening before the case is ruled on by normal courts. In these cases 6 out of 9 jurors must find against the defendant, and may not be overruled in cases of acquittal.

Sweden has no tradition of using juries in most types of criminal or civil trial. The sole exception, since 1815, is in cases involving freedom of the press, prosecuted under Chapter 7 of the Freedom of the Press Act, part of Sweden's constitution. The most frequently prosecuted offence under this act is defamation, although in total eighteen offences, including high treason and espionage, are covered. These cases are tried in district courts (first tier courts) by a jury of nine laymen.

The jury in press freedom cases rules only on the facts of the case and the question of guilt or innocence. The trial judge may overrule a jury's guilty verdict, but may not overrule an acquittal. A conviction requires a majority verdict of 6–3. Sentencing is the sole prerogative of judges.

Jury members must be Swedish citizens and resident in the county in which the case is being heard. They must be of sound judgement and known for their independence and integrity. Combined, they should represent a range of social groups and opinions, as well as all parts of the county. It is the county council that have the responsibility to appoints juries for a tenure of four years under which they may serve in multiple cases. The appointed jurymen are divided into two groups, in most counties the first with sixteen members and the second with eight. From this pool of available jurymen the court hears and excludes those with conflicts of interest in the case, after which the defendants and plaintiffs have the right to exclude a number of members, varying by county and group. The final jury is then randomly selected by drawing of lots.

Juries are not used in other criminal and civil cases. For most other cases in the first and second tier courts lay judges sit alongside professional judges. Lay judges participate in deciding both the facts of the case and sentencing. Lay judges are appointed by local authorities, or in practice by the political parties represented on the authorities. Lay judges are therefore usually selected from among nominees of ruling political parties.

United Kingdom

See also: Jury of matronsEngland and Wales

Main article: Juries in England and WalesIn England and Wales jury trials are used for criminal cases, requiring 12 jurors (between the ages of 18 and 75), although the trial may continue with as few as 9. The right to a jury trial has been enshrined in English law since Magna Carta in 1215, and is most common in serious cases, although the defendant can insist on a jury trial for most criminal cases. Jury trials in complex fraud cases have been described by some members and appointees of the Labour Party as expensive and time-consuming. In contrast, the Bar Council, Liberty and other political parties have supported the idea that trial by jury is at the heart of the judicial system and placed the blame for a few complicated jury trials failing on inadequate preparation by the prosecution.

On 18 June 2009 the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Judge, sitting in the Court of Appeal, made English legal history by ruling that a criminal trial in the Crown Court could take place without a jury, under the provisions of the Criminal Justice Act 2003.

Jury trials are also available for some few areas of civil law (for example defamation cases and those involving police conduct); these also require 12 jurors (9 in the County Court). However less than 1% of civil trials involve juries. At the new Manchester Civil Justice Centre, constructed in 2008, fewer than 10 of the 48 courtrooms had jury facilities.

Northern Ireland

During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, jury trials were suspended and trials took place before Diplock Courts. These were essentially bench trials before judges only. This was to combat jury nullification and the intimidation of juries.

Scotland

Main article: Trial by jury in ScotlandIn Scottish criminal trials, juries are composed of fifteen residents, while in civil trials there is a jury of 12 people.

Etymology

The word jury derives from Latin iurare ("to swear"). Juries are most common in common law adversarial-system jurisdictions. In the modern system, juries act as triers of fact, while judges act as triers of law (but see nullification). A trial without a jury (in which both questions of fact and questions of law are decided by a judge) is known as a bench trial.

See also

References

- "CURRENT GRAND JURY REPORTS – Miami Dade Office of the State Attorney". Miamisao.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ^ Howlin, Níamh (August 2011). ""The Terror of their Lives": Irish Jurors' Experiences". Law and History Review. 29 (3): 703–761. doi:10.1017/S0738248011000319. hdl:10197/4259. ISSN 0738-2480.

- See, e.g., Section 1245.1 of Pennsylvania's codified laws regarding coroners. http://www.pacoroners.org/Laws.php Archived 2013-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- See, e.g., Inquest Schedule, Jury Findings and Vedicts (2013) of British Columbia. http://www.pssg.gov.bc.ca/coroners/schedule/index.htm Archived 2016-02-13 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved March 8, 2013)

- "Citizens' assemblies: New ways to democratize democracy" (PDF). Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, September 2021. Retrieved 2024-12-21.