| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Amplitude-shift keying" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: this article need neutral and better phrasing. Please help improve this article if you can. (November 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Passband modulation |

|---|

|

| Analog modulation |

| Digital modulation |

| Hierarchical modulation |

| Spread spectrum |

| See also |

Amplitude-shift keying (ASK) is a form of amplitude modulation that represents digital data as variations in the amplitude of a carrier wave. In an ASK system, a symbol, representing one or more bits, is sent by transmitting a fixed-amplitude carrier wave at a fixed frequency for a specific time duration. For example, if each symbol represents a single bit, then the carrier signal could be transmitted at nominal amplitude when the input value is 1, but transmitted at reduced amplitude or not at all when the input value is 0.

Method

Any digital modulation scheme uses a finite number of distinct signals to represent digital data. ASK uses a finite number of amplitudes, each assigned a unique pattern of binary digits. Usually, each amplitude encodes an equal number of bits. Each pattern of bits forms the symbol that is represented by the particular amplitude. The demodulator, which is designed specifically for the symbol-set used by the modulator, determines the amplitude of the received signal and maps it back to the symbol it represents, thus recovering the original data. Frequency and phase of the carrier are kept constant.

Like AM, an ASK is also linear and sensitive to atmospheric noise, distortions, propagation conditions on different routes in PSTN, etc. Both ASK modulation and demodulation processes are relatively inexpensive. The ASK technique is also commonly used to transmit digital data over optical fiber. For LED transmitters, binary 1 is represented by a short pulse of light and binary 0 by the absence of light. Laser transmitters normally have a fixed "bias" current that causes the device to emit a low light level. This low level represents binary 0, while a higher-amplitude lightwave represents binary 1.

The simplest and most common form of ASK operates as a switch, using the presence of a carrier wave to indicate a binary one and its absence to indicate a binary zero. This type of modulation is called on-off keying (OOK), and is used at radio frequencies to transmit Morse code (referred to as continuous wave operation),

More sophisticated encoding schemes have been developed which represent data in groups using additional amplitude levels. For instance, a four-level encoding scheme can represent two bits with each shift in amplitude; an eight-level scheme can represent three bits; and so on. These forms of amplitude-shift keying require a high signal-to-noise ratio for their recovery, as by their nature much of the signal is transmitted at reduced power.

ASK system can be divided into three blocks. The first one represents the transmitter, the second one is a linear model of the effects of the channel, the third one shows the structure of the receiver. The following notation is used:

- ht(f) is the carrier signal for the transmission

- hc(f) is the impulse response of the channel

- n(t) is the noise introduced by the channel

- hr(f) is the filter at the receiver

- L is the number of levels that are used for transmission

- Ts is the time between the generation of two symbols

Different symbols are represented with different voltages. If the maximum allowed value for the voltage is A, then all the possible values are in the range and they are given by:

the difference between one voltage and the other is:

Considering the picture, the symbols v are generated randomly by the source S, then the impulse generator creates impulses with an area of v. These impulses are sent to the filter ht to be sent through the channel. In other words, for each symbol a different carrier wave is sent with the relative amplitude.

Out of the transmitter, the signal s(t) can be expressed in the form:

In the receiver, after the filtering through hr (t) the signal is:

where we use the notation:

where * indicates the convolution between two signals. After the A/D conversion the signal z can be expressed in the form:

In this relationship, the second term represents the symbol to be extracted. The others are unwanted: the first one is the effect of noise, the third one is due to the intersymbol interference.

If the filters are chosen so that g(t) will satisfy the Nyquist ISI criterion, then there will be no intersymbol interference and the value of the sum will be zero, so:

the transmission will be affected only by noise.

Probability of error

The probability density function of having an error of a given size can be modelled by a Gaussian function; the mean value will be the relative sent value, and its variance will be given by:

where is the spectral density of the noise within the band and Hr (f) is the continuous Fourier transform of the impulse response of the filter hr (f).

The probability of making an error is given by:

where, for example, is the conditional probability of making an error given that a symbol v0 has been sent and is the probability of sending a symbol v0.

If the probability of sending any symbol is the same, then:

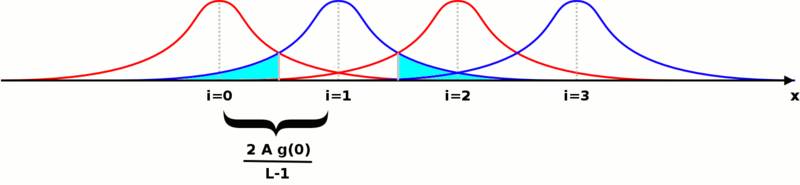

If we represent all the probability density functions on the same plot against the possible value of the voltage to be transmitted, we get a picture like this (the particular case of is shown):

The probability of making an error after a single symbol has been sent is the area of the Gaussian function falling under the functions for the other symbols. It is shown in cyan for just one of them. If we call the area under one side of the Gaussian, the sum of all the areas will be: . The total probability of making an error can be expressed in the form:

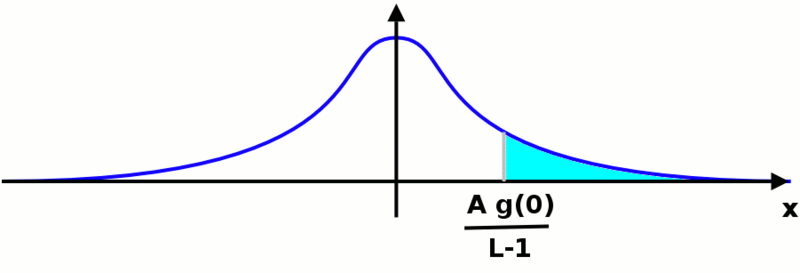

We now have to calculate the value of . In order to do that, we can move the origin of the reference wherever we want: the area below the function will not change. We are in a situation like the one shown in the following picture:

it does not matter which Gaussian function we are considering, the area we want to calculate will be the same. The value we are looking for will be given by the following integral:

where is the complementary error function. Putting all these results together, the probability to make an error is:

from this formula we can easily understand that the probability to make an error decreases if the maximum amplitude of the transmitted signal or the amplification of the system becomes greater; on the other hand, it increases if the number of levels or the power of noise becomes greater.

This relationship is valid when there is no intersymbol interference, i.e. is a Nyquist function.

See also

- Frequency-shift keying (FSK)

References

- ^ "Telecommunication - Modulation, Signals, Frequency | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2024-09-27. Retrieved 2024-11-02.

External links

- Calculating the Sensitivity of an Amplitude Shift Keying (ASK) Receiver Archived 2009-08-29 at the Wayback Machine

is the spectral density of the noise within the band and Hr (f) is the continuous Fourier transform of the impulse response of the filter hr (f).

is the spectral density of the noise within the band and Hr (f) is the continuous Fourier transform of the impulse response of the filter hr (f).

is the conditional probability of making an error given that a symbol v0 has been sent and

is the conditional probability of making an error given that a symbol v0 has been sent and  is the probability of sending a symbol v0.

is the probability of sending a symbol v0.

is shown):

is shown):

the area under one side of the Gaussian, the sum of all the areas will be:

the area under one side of the Gaussian, the sum of all the areas will be:  . The total probability of making an error can be expressed in the form:

. The total probability of making an error can be expressed in the form:

is the complementary error function. Putting all these results together, the probability to make an error is:

is the complementary error function. Putting all these results together, the probability to make an error is:

is a

is a