| Solid angle | |

|---|---|

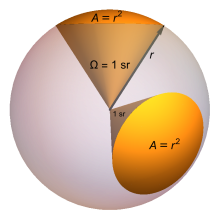

Visual representation of a solid angle Visual representation of a solid angle | |

| Common symbols | Ω |

| SI unit | steradian |

| Other units | Square degree, spat (angular unit) |

| In SI base units | m/m |

| Conserved? | No |

| Derivations from other quantities | |

| Dimension | |

In geometry, a solid angle (symbol: Ω) is a measure of the amount of the field of view from some particular point that a given object covers. That is, it is a measure of how large the object appears to an observer looking from that point. The point from which the object is viewed is called the apex of the solid angle, and the object is said to subtend its solid angle at that point.

In the International System of Units (SI), a solid angle is expressed in a dimensionless unit called a steradian (symbol: sr), which is equal to one square radian, sr = rad. One steradian corresponds to one unit of area (of any shape) on the unit sphere surrounding the apex, so an object that blocks all rays from the apex would cover a number of steradians equal to the total surface area of the unit sphere, . Solid angles can also be measured in squares of angular measures such as degrees, minutes, and seconds.

A small object nearby may subtend the same solid angle as a larger object farther away. For example, although the Moon is much smaller than the Sun, it is also much closer to Earth. Indeed, as viewed from any point on Earth, both objects have approximately the same solid angle (and therefore apparent size). This is evident during a solar eclipse.

Definition and properties

See also: Spherical polygon areaThe magnitude of an object's solid angle in steradians is equal to the area of the segment of a unit sphere, centered at the apex, that the object covers. Giving the area of a segment of a unit sphere in steradians is analogous to giving the length of an arc of a unit circle in radians. Just as the magnitude of a plane angle in radians at the vertex of a circular sector is the ratio of the length of its arc to its radius, the magnitude of a solid angle in steradians is the ratio of the area covered on a sphere by an object to the square of the radius of the sphere. The formula for the magnitude of the solid angle in steradians is

where is the area (of any shape) on the surface of the sphere and is the radius of the sphere.

Solid angles are often used in astronomy, physics, and in particular astrophysics. The solid angle of an object that is very far away is roughly proportional to the ratio of area to squared distance. Here "area" means the area of the object when projected along the viewing direction.

The solid angle of a sphere measured from any point in its interior is 4π sr. The solid angle subtended at the center of a cube by one of its faces is one-sixth of that, or 2π/3 sr. The solid angle subtended at the corner of a cube (an octant) or spanned by a spherical octant is π/2 sr, one-eight of the solid angle of a sphere.

Solid angles can also be measured in square degrees (1 sr = (180/π) square degrees), in square arc-minutes and square arc-seconds, or in fractions of the sphere (1 sr = 1/4π fractional area), also known as spat (1 sp = 4π sr).

In spherical coordinates there is a formula for the differential,

where θ is the colatitude (angle from the North Pole) and φ is the longitude.

The solid angle for an arbitrary oriented surface S subtended at a point P is equal to the solid angle of the projection of the surface S to the unit sphere with center P, which can be calculated as the surface integral:

where is the unit vector corresponding to , the position vector of an infinitesimal area of surface dS with respect to point P, and where represents the unit normal vector to dS. Even if the projection on the unit sphere to the surface S is not isomorphic, the multiple folds are correctly considered according to the surface orientation described by the sign of the scalar product .

Thus one can approximate the solid angle subtended by a small facet having flat surface area dS, orientation , and distance r from the viewer as:

where the surface area of a sphere is A = 4πr.

Practical applications

- Defining luminous intensity and luminance, and the correspondent radiometric quantities radiant intensity and radiance

- Calculating spherical excess E of a spherical triangle

- The calculation of potentials by using the boundary element method (BEM)

- Evaluating the size of ligands in metal complexes, see ligand cone angle

- Calculating the electric field and magnetic field strength around charge distributions

- Deriving Gauss's Law

- Calculating emissive power and irradiation in heat transfer

- Calculating cross sections in Rutherford scattering

- Calculating cross sections in Raman scattering

- The solid angle of the acceptance cone of the optical fiber

- The computation of nodal densities in meshes.

Solid angles for common objects

Cone, spherical cap, hemisphere

The solid angle of a cone with its apex at the apex of the solid angle, and with apex angle 2θ, is the area of a spherical cap on a unit sphere

For small θ such that cos θ ≈ 1 − θ/2 this reduces to πθ, the area of a circle.

The above is found by computing the following double integral using the unit surface element in spherical coordinates:

This formula can also be derived without the use of calculus.

Over 2200 years ago Archimedes proved that the surface area of a spherical cap is always equal to the area of a circle whose radius equals the distance from the rim of the spherical cap to the point where the cap's axis of symmetry intersects the cap.

In the above coloured diagram this radius is given as

In the adjacent black & white diagram this radius is given as "t".

Hence for a unit sphere the solid angle of the spherical cap is given as

When θ = π/2, the spherical cap becomes a hemisphere having a solid angle 2π.

The solid angle of the complement of the cone is

This is also the solid angle of the part of the celestial sphere that an astronomical observer positioned at latitude θ can see as the Earth rotates. At the equator all of the celestial sphere is visible; at either pole, only one half.

The solid angle subtended by a segment of a spherical cap cut by a plane at angle γ from the cone's axis and passing through the cone's apex can be calculated by the formula

For example, if γ = −θ, then the formula reduces to the spherical cap formula above: the first term becomes π, and the second π cos θ.

Tetrahedron

Let OABC be the vertices of a tetrahedron with an origin at O subtended by the triangular face ABC where are the vector positions of the vertices A, B and C. Define the vertex angle θa to be the angle BOC and define θb, θc correspondingly. Let be the dihedral angle between the planes that contain the tetrahedral faces OAC and OBC and define , correspondingly. The solid angle Ω subtended by the triangular surface ABC is given by

This follows from the theory of spherical excess and it leads to the fact that there is an analogous theorem to the theorem that "The sum of internal angles of a planar triangle is equal to π", for the sum of the four internal solid angles of a tetrahedron as follows:

where ranges over all six of the dihedral angles between any two planes that contain the tetrahedral faces OAB, OAC, OBC and ABC.

A useful formula for calculating the solid angle of the tetrahedron at the origin O that is purely a function of the vertex angles θa, θb, θc is given by L'Huilier's theorem as

where

Another interesting formula involves expressing the vertices as vectors in 3 dimensional space. Let be the vector positions of the vertices A, B and C, and let a, b, and c be the magnitude of each vector (the origin-point distance). The solid angle Ω subtended by the triangular surface ABC is:

where

denotes the scalar triple product of the three vectors and denotes the scalar product.

Care must be taken here to avoid negative or incorrect solid angles. One source of potential errors is that the scalar triple product can be negative if a, b, c have the wrong winding. Computing the absolute value is a sufficient solution since no other portion of the equation depends on the winding. The other pitfall arises when the scalar triple product is positive but the divisor is negative. In this case returns a negative value that must be increased by π.

Pyramid

The solid angle of a four-sided right rectangular pyramid with apex angles a and b (dihedral angles measured to the opposite side faces of the pyramid) is

If both the side lengths (α and β) of the base of the pyramid and the distance (d) from the center of the base rectangle to the apex of the pyramid (the center of the sphere) are known, then the above equation can be manipulated to give

The solid angle of a right n-gonal pyramid, where the pyramid base is a regular n-sided polygon of circumradius r, with a pyramid height h is

The solid angle of an arbitrary pyramid with an n-sided base defined by the sequence of unit vectors representing edges {s1, s2}, ... sn can be efficiently computed by:

where parentheses (* *) is a scalar product and square brackets is a scalar triple product, and i is an imaginary unit. Indices are cycled: s0 = sn and s1 = sn + 1. The complex products add the phase associated with each vertex angle of the polygon. However, a multiple of is lost in the branch cut of and must be kept track of separately. Also, the running product of complex phases must scaled occasionally to avoid underflow in the limit of nearly parallel segments.

Latitude-longitude rectangle

The solid angle of a latitude-longitude rectangle on a globe is where φN and φS are north and south lines of latitude (measured from the equator in radians with angle increasing northward), and θE and θW are east and west lines of longitude (where the angle in radians increases eastward). Mathematically, this represents an arc of angle ϕN − ϕS swept around a sphere by θE − θW radians. When longitude spans 2π radians and latitude spans π radians, the solid angle is that of a sphere.

A latitude-longitude rectangle should not be confused with the solid angle of a rectangular pyramid. All four sides of a rectangular pyramid intersect the sphere's surface in great circle arcs. With a latitude-longitude rectangle, only lines of longitude are great circle arcs; lines of latitude are not.

Celestial objects

By using the definition of angular diameter, the formula for the solid angle of a celestial object can be defined in terms of the radius of the object, , and the distance from the observer to the object, :

By inputting the appropriate average values for the Sun and the Moon (in relation to Earth), the average solid angle of the Sun is 6.794×10 steradians and the average solid angle of the Moon is 6.418×10 steradians. In terms of the total celestial sphere, the Sun and the Moon subtend average fractional areas of 0.0005406% (5.406 ppm) and 0.0005107% (5.107 ppm), respectively. As these solid angles are about the same size, the Moon can cause both total and annular solar eclipses depending on the distance between the Earth and the Moon during the eclipse.

Solid angles in arbitrary dimensions

The solid angle subtended by the complete (d − 1)-dimensional spherical surface of the unit sphere in d-dimensional Euclidean space can be defined in any number of dimensions d. One often needs this solid angle factor in calculations with spherical symmetry. It is given by the formula where Γ is the gamma function. When d is an integer, the gamma function can be computed explicitly. It follows that

This gives the expected results of 4π steradians for the 3D sphere bounded by a surface of area 4πr and 2π radians for the 2D circle bounded by a circumference of length 2πr. It also gives the slightly less obvious 2 for the 1D case, in which the origin-centered 1D "sphere" is the interval [−r, r] and this is bounded by two limiting points.

The counterpart to the vector formula in arbitrary dimension was derived by Aomoto and independently by Ribando. It expresses them as an infinite multivariate Taylor series: Given d unit vectors defining the angle, let V denote the matrix formed by combining them so the ith column is , and . The variables form a multivariable . For a "congruent" integer multiexponent define . Note that here = non-negative integers, or natural numbers beginning with 0. The notation for means the variable , similarly for the exponents . Hence, the term means the sum over all terms in in which l appears as either the first or second index. Where this series converges, it converges to the solid angle defined by the vectors.

References

- "octant". PlanetMath.org. 2013-03-22. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- Falla, Romain (2023). "Mesh adaption for two-dimensional bounded and free-surface flows with the particle finite element method". Computational Particle Mechanics. 10 (5): 1049–1076. Bibcode:2023CPM....10.1049F. doi:10.1007/s40571-022-00541-2.

- "Archimedes on Spheres and Cylinders". Math Pages. 2015.

- ^ Mazonka, Oleg (2012). "Solid Angle of Conical Surfaces, Polyhedral Cones, and Intersecting Spherical Caps". arXiv:1205.1396 .

- Hopf, Heinz (1940). "Selected Chapters of Geometry" (PDF). ETH Zurich: 1–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-21.

- "L'Huilier's Theorem – from Wolfram MathWorld". Mathworld.wolfram.com. 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- "Spherical Excess – from Wolfram MathWorld". Mathworld.wolfram.com. 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- Eriksson, Folke (1990). "On the measure of solid angles". Math. Mag. 63 (3): 184–187. doi:10.2307/2691141. JSTOR 2691141.

- Van Oosterom, A; Strackee, J (1983). "The Solid Angle of a Plane Triangle". IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME-30 (2): 125–126. doi:10.1109/TBME.1983.325207. PMID 6832789. S2CID 22669644.

- "Area of a Latitude-Longitude Rectangle". The Math Forum @ Drexel. 2003.

- Jackson, FM (1993). "Polytopes in Euclidean n-space". Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and Its Applications. 29 (11/12): 172–174.

- Aomoto, Kazuhiko (1977). "Analytic structure of Schläfli function". Nagoya Math. J. 68: 1–16. doi:10.1017/s0027763000017839.

- Beck, M.; Robins, S.; Sam, S. V. (2010). "Positivity theorems for solid-angle polynomials". Contributions to Algebra and Geometry. 51 (2): 493–507. arXiv:0906.4031. Bibcode:2009arXiv0906.4031B.

- Ribando, Jason M. (2006). "Measuring Solid Angles Beyond Dimension Three". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 36 (3): 479–487. doi:10.1007/s00454-006-1253-4.

Further reading

- Jaffey, A. H. (1954). "Solid angle subtended by a circular aperture at point and spread sources: formulas and some tables". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 25 (4): 349–354. Bibcode:1954RScI...25..349J. doi:10.1063/1.1771061.

- Masket, A. Victor (1957). "Solid angle contour integrals, series, and tables". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 28 (3): 191. Bibcode:1957RScI...28..191M. doi:10.1063/1.1746479.

- Naito, Minoru (1957). "A method of calculating the solid angle subtended by a circular aperture". J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12 (10): 1122–1129. Bibcode:1957JPSJ...12.1122N. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.12.1122.

- Paxton, F. (1959). "Solid angle calculation for a circular disk". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 30 (4): 254. Bibcode:1959RScI...30..254P. doi:10.1063/1.1716590.

- Khadjavi, A. (1968). "Calculation of solid angle subtended by rectangular apertures". J. Opt. Soc. Am. 58 (10): 1417–1418. Bibcode:1968JOSA...58.1417K. doi:10.1364/JOSA.58.001417.

- Gardner, R. P.; Carnesale, A. (1969). "The solid angle subtended at a point by a circular disk". Nucl. Instrum. Methods. 73 (2): 228–230. Bibcode:1969NucIM..73..228G. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(69)90214-6.

- Gardner, R. P.; Verghese, K. (1971). "On the solid angle subtended by a circular disk". Nucl. Instrum. Methods. 93 (1): 163–167. Bibcode:1971NucIM..93..163G. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(71)90155-8.

- Gotoh, H.; Yagi, H. (1971). "Solid angle subtended by a rectangular slit". Nucl. Instrum. Methods. 96 (3): 485–486. Bibcode:1971NucIM..96..485G. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(71)90624-0.

- Cook, J. (1980). "Solid angle subtended by a two rectangles". Nucl. Instrum. Methods. 178 (2–3): 561–564. Bibcode:1980NucIM.178..561C. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(80)90838-1.

- Asvestas, John S..; Englund, David C. (1994). "Computing the solid angle subtended by a planar figure". Opt. Eng. 33 (12): 4055–4059. Bibcode:1994OptEn..33.4055A. doi:10.1117/12.183402. Erratum ibid. vol 50 (2011) page 059801.

- Tryka, Stanislaw (1997). "Angular distribution of the solid angle at a point subtended by a circular disk". Opt. Commun. 137 (4–6): 317–333. Bibcode:1997OptCo.137..317T. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(96)00789-4.

- Prata, M. J. (2004). "Analytical calculation of the solid angle subtended by a circular disc detector at a point cosine source". Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 521 (2–3): 576. arXiv:math-ph/0305034. Bibcode:2004NIMPA.521..576P. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2003.10.098. S2CID 15266291.

- Timus, D. M.; Prata, M. J.; Kalla, S. L.; Abbas, M. I.; Oner, F.; Galiano, E. (2007). "Some further analytical results on the solid angle subtended at a point by a circular disk using elliptic integrals". Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 580: 149–152. Bibcode:2007NIMPA.580..149T. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2007.05.055.

External links

- Arthur P. Norton, A Star Atlas, Gall and Inglis, Edinburgh, 1969.

- M. G. Kendall, A Course in the Geometry of N Dimensions, No. 8 of Griffin's Statistical Monographs & Courses, ed. M. G. Kendall, Charles Griffin & Co. Ltd, London, 1961

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Solid Angle". MathWorld.

. Solid angles can also be measured in squares of angular measures such as

. Solid angles can also be measured in squares of angular measures such as

is the area (of any shape) on the surface of the sphere and

is the area (of any shape) on the surface of the sphere and  is the radius of the sphere.

is the radius of the sphere.

is the

is the  , the

, the  represents the unit

represents the unit  .

.

In the adjacent black & white diagram this radius is given as "t".

In the adjacent black & white diagram this radius is given as "t".

are the vector positions of the vertices A, B and C. Define the

are the vector positions of the vertices A, B and C. Define the  be the

be the  ,

,  correspondingly. The solid angle Ω subtended by the triangular surface ABC is given by

correspondingly. The solid angle Ω subtended by the triangular surface ABC is given by

ranges over all six of the dihedral angles between any two planes that contain the tetrahedral faces OAB, OAC, OBC and ABC.

ranges over all six of the dihedral angles between any two planes that contain the tetrahedral faces OAB, OAC, OBC and ABC.

denotes the

denotes the

is lost in the branch cut of

is lost in the branch cut of  and must be kept track of separately. Also, the running product of complex phases must scaled occasionally to avoid underflow in the limit of nearly parallel segments.

and must be kept track of separately. Also, the running product of complex phases must scaled occasionally to avoid underflow in the limit of nearly parallel segments.

where φN and φS are north and south lines of

where φN and φS are north and south lines of  , and the distance from the observer to the object,

, and the distance from the observer to the object,  :

:

where Γ is the

where Γ is the

Given d unit vectors

Given d unit vectors  defining the angle, let V denote the matrix formed by combining them so the ith column is

defining the angle, let V denote the matrix formed by combining them so the ith column is  . The variables

. The variables  form a multivariable

form a multivariable  . For a "congruent" integer multiexponent

. For a "congruent" integer multiexponent  define

define  . Note that here

. Note that here  = non-negative integers, or natural numbers beginning with 0. The notation

= non-negative integers, or natural numbers beginning with 0. The notation  for

for  means the variable

means the variable  , similarly for the exponents

, similarly for the exponents  .

Hence, the term

.

Hence, the term  means the sum over all terms in

means the sum over all terms in  in which l appears as either the first or second index.

Where this series converges, it converges to the solid angle defined by the vectors.

in which l appears as either the first or second index.

Where this series converges, it converges to the solid angle defined by the vectors.