Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules. The atoms and molecules are allowed to interact for a fixed period of time, giving a view of the dynamic "evolution" of the system. In the most common version, the trajectories of atoms and molecules are determined by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces between the particles and their potential energies are often calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields. The method is applied mostly in chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics.

Because molecular systems typically consist of a vast number of particles, it is impossible to determine the properties of such complex systems analytically; MD simulation circumvents this problem by using numerical methods. However, long MD simulations are mathematically ill-conditioned, generating cumulative errors in numerical integration that can be minimized with proper selection of algorithms and parameters, but not eliminated.

For systems that obey the ergodic hypothesis, the evolution of one molecular dynamics simulation may be used to determine the macroscopic thermodynamic properties of the system: the time averages of an ergodic system correspond to microcanonical ensemble averages. MD has also been termed "statistical mechanics by numbers" and "Laplace's vision of Newtonian mechanics" of predicting the future by animating nature's forces and allowing insight into molecular motion on an atomic scale.

History

MD was originally developed in the early 1950s, following earlier successes with Monte Carlo simulations—which themselves date back to the eighteenth century, in the Buffon's needle problem for example—but was popularized for statistical mechanics at Los Alamos National Laboratory by Marshall Rosenbluth and Nicholas Metropolis in what is known today as the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm. Interest in the time evolution of N-body systems dates much earlier to the seventeenth century, beginning with Isaac Newton, and continued into the following century largely with a focus on celestial mechanics and issues such as the stability of the solar system. Many of the numerical methods used today were developed during this time period, which predates the use of computers; for example, the most common integration algorithm used today, the Verlet integration algorithm, was used as early as 1791 by Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre. Numerical calculations with these algorithms can be considered to be MD done "by hand".

As early as 1941, integration of the many-body equations of motion was carried out with analog computers. Some undertook the labor-intensive work of modeling atomic motion by constructing physical models, e.g., using macroscopic spheres. The aim was to arrange them in such a way as to replicate the structure of a liquid and use this to examine its behavior. J.D. Bernal describes this process in 1962, writing:

... I took a number of rubber balls and stuck them together with rods of a selection of different lengths ranging from 2.75 to 4 inches. I tried to do this in the first place as casually as possible, working in my own office, being interrupted every five minutes or so and not remembering what I had done before the interruption.

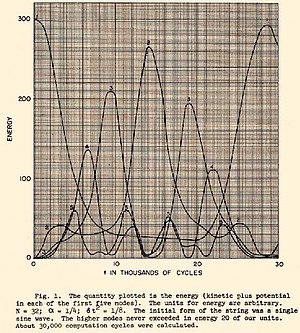

Following the discovery of microscopic particles and the development of computers, interest expanded beyond the proving ground of gravitational systems to the statistical properties of matter. In an attempt to understand the origin of irreversibility, Enrico Fermi proposed in 1953, and published in 1955, the use of the early computer MANIAC I, also at Los Alamos National Laboratory, to solve the time evolution of the equations of motion for a many-body system subject to several choices of force laws. Today, this seminal work is known as the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem. The time evolution of the energy from the original work is shown in the figure to the right.

In 1957, Berni Alder and Thomas Wainwright used an IBM 704 computer to simulate perfectly elastic collisions between hard spheres. In 1960, in perhaps the first realistic simulation of matter, J.B. Gibson et al. simulated radiation damage of solid copper by using a Born–Mayer type of repulsive interaction along with a cohesive surface force. In 1964, Aneesur Rahman published simulations of liquid argon that used a Lennard-Jones potential; calculations of system properties, such as the coefficient of self-diffusion, compared well with experimental data. Today, the Lennard-Jones potential is still one of the most frequently used intermolecular potentials. It is used for describing simple substances (a.k.a. Lennard-Jonesium) for conceptual and model studies and as a building block in many force fields of real substances.

Areas of application and limits

First used in theoretical physics, the molecular dynamics method gained popularity in materials science soon afterward, and since the 1970s it has also been commonly used in biochemistry and biophysics. MD is frequently used to refine 3-dimensional structures of proteins and other macromolecules based on experimental constraints from X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy. In physics, MD is used to examine the dynamics of atomic-level phenomena that cannot be observed directly, such as thin film growth and ion subplantation, and to examine the physical properties of nanotechnological devices that have not or cannot yet be created. In biophysics and structural biology, the method is frequently applied to study the motions of macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, which can be useful for interpreting the results of certain biophysical experiments and for modeling interactions with other molecules, as in ligand docking. In principle, MD can be used for ab initio prediction of protein structure by simulating folding of the polypeptide chain from a random coil.

The results of MD simulations can be tested through comparison to experiments that measure molecular dynamics, of which a popular method is NMR spectroscopy. MD-derived structure predictions can be tested through community-wide experiments in Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP), although the method has historically had limited success in this area. Michael Levitt, who shared the Nobel Prize partly for the application of MD to proteins, wrote in 1999 that CASP participants usually did not use the method due to "... a central embarrassment of molecular mechanics, namely that energy minimization or molecular dynamics generally leads to a model that is less like the experimental structure". Improvements in computational resources permitting more and longer MD trajectories, combined with modern improvements in the quality of force field parameters, have yielded some improvements in both structure prediction and homology model refinement, without reaching the point of practical utility in these areas; many identify force field parameters as a key area for further development.

MD simulation has been reported for pharmacophore development and drug design. For example, Pinto et al. implemented MD simulations of Bcl-xL complexes to calculate average positions of critical amino acids involved in ligand binding. Carlson et al. implemented molecular dynamics simulations to identify compounds that complement a receptor while causing minimal disruption to the conformation and flexibility of the active site. Snapshots of the protein at constant time intervals during the simulation were overlaid to identify conserved binding regions (conserved in at least three out of eleven frames) for pharmacophore development. Spyrakis et al. relied on a workflow of MD simulations, fingerprints for ligands and proteins (FLAP) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to identify the best ligand-protein conformations to act as pharmacophore templates based on retrospective ROC analysis of the resulting pharmacophores. In an attempt to ameliorate structure-based drug discovery modeling, vis-à-vis the need for many modeled compounds, Hatmal et al. proposed a combination of MD simulation and ligand-receptor intermolecular contacts analysis to discern critical intermolecular contacts (binding interactions) from redundant ones in a single ligand–protein complex. Critical contacts can then be converted into pharmacophore models that can be used for virtual screening.

An important factor is intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which are not explicitly included in modern force fields, but described as Coulomb interactions of atomic point charges. This is a crude approximation because hydrogen bonds have a partially quantum mechanical and chemical nature. Furthermore, electrostatic interactions are usually calculated using the dielectric constant of a vacuum, even though the surrounding aqueous solution has a much higher dielectric constant. Thus, using the macroscopic dielectric constant at short interatomic distances is questionable. Finally, van der Waals interactions in MD are usually described by Lennard-Jones potentials based on the Fritz London theory that is only applicable in a vacuum. However, all types of van der Waals forces are ultimately of electrostatic origin and therefore depend on dielectric properties of the environment. The direct measurement of attraction forces between different materials (as Hamaker constant) shows that "the interaction between hydrocarbons across water is about 10% of that across vacuum". The environment-dependence of van der Waals forces is neglected in standard simulations, but can be included by developing polarizable force fields.

Design constraints

The design of a molecular dynamics simulation should account for the available computational power. Simulation size (n = number of particles), timestep, and total time duration must be selected so that the calculation can finish within a reasonable time period. However, the simulations should be long enough to be relevant to the time scales of the natural processes being studied. To make statistically valid conclusions from the simulations, the time span simulated should match the kinetics of the natural process. Otherwise, it is analogous to making conclusions about how a human walks when only looking at less than one footstep. Most scientific publications about the dynamics of proteins and DNA use data from simulations spanning nanoseconds (10 s) to microseconds (10 s). To obtain these simulations, several CPU-days to CPU-years are needed. Parallel algorithms allow the load to be distributed among CPUs; an example is the spatial or force decomposition algorithm.

During a classical MD simulation, the most CPU intensive task is the evaluation of the potential as a function of the particles' internal coordinates. Within that energy evaluation, the most expensive one is the non-bonded or non-covalent part. In big O notation, common molecular dynamics simulations scale by if all pair-wise electrostatic and van der Waals interactions must be accounted for explicitly. This computational cost can be reduced by employing electrostatics methods such as particle mesh Ewald summation ( ), particle-particle-particle mesh (PM), or good spherical cutoff methods ( ).

Another factor that impacts total CPU time needed by a simulation is the size of the integration timestep. This is the time length between evaluations of the potential. The timestep must be chosen small enough to avoid discretization errors (i.e., smaller than the period related to fastest vibrational frequency in the system). Typical timesteps for classical MD are on the order of 1 femtosecond (10 s). This value may be extended by using algorithms such as the SHAKE constraint algorithm, which fix the vibrations of the fastest atoms (e.g., hydrogens) into place. Multiple time scale methods have also been developed, which allow extended times between updates of slower long-range forces.

For simulating molecules in a solvent, a choice should be made between an explicit and implicit solvent. Explicit solvent particles (such as the TIP3P, SPC/E and SPC-f water models) must be calculated expensively by the force field, while implicit solvents use a mean-field approach. Using an explicit solvent is computationally expensive, requiring inclusion of roughly ten times more particles in the simulation. But the granularity and viscosity of explicit solvent is essential to reproduce certain properties of the solute molecules. This is especially important to reproduce chemical kinetics.

In all kinds of molecular dynamics simulations, the simulation box size must be large enough to avoid boundary condition artifacts. Boundary conditions are often treated by choosing fixed values at the edges (which may cause artifacts), or by employing periodic boundary conditions in which one side of the simulation loops back to the opposite side, mimicking a bulk phase (which may cause artifacts too).

Microcanonical ensemble (NVE)

In the microcanonical ensemble, the system is isolated from changes in moles (N), volume (V), and energy (E). It corresponds to an adiabatic process with no heat exchange. A microcanonical molecular dynamics trajectory may be seen as an exchange of potential and kinetic energy, with total energy being conserved. For a system of N particles with coordinates and velocities , the following pair of first order differential equations may be written in Newton's notation as

The potential energy function of the system is a function of the particle coordinates . It is referred to simply as the potential in physics, or the force field in chemistry. The first equation comes from Newton's laws of motion; the force acting on each particle in the system can be calculated as the negative gradient of .

For every time step, each particle's position and velocity may be integrated with a symplectic integrator method such as Verlet integration. The time evolution of and is called a trajectory. Given the initial positions (e.g., from theoretical knowledge) and velocities (e.g., randomized Gaussian), we can calculate all future (or past) positions and velocities.

One frequent source of confusion is the meaning of temperature in MD. Commonly we have experience with macroscopic temperatures, which involve a huge number of particles, but temperature is a statistical quantity. If there is a large enough number of atoms, statistical temperature can be estimated from the instantaneous temperature, which is found by equating the kinetic energy of the system to nkBT/2, where n is the number of degrees of freedom of the system.

A temperature-related phenomenon arises due to the small number of atoms that are used in MD simulations. For example, consider simulating the growth of a copper film starting with a substrate containing 500 atoms and a deposition energy of 100 eV. In the real world, the 100 eV from the deposited atom would rapidly be transported through and shared among a large number of atoms ( or more) with no big change in temperature. When there are only 500 atoms, however, the substrate is almost immediately vaporized by the deposition. Something similar happens in biophysical simulations. The temperature of the system in NVE is naturally raised when macromolecules such as proteins undergo exothermic conformational changes and binding.

Canonical ensemble (NVT)

In the canonical ensemble, amount of substance (N), volume (V) and temperature (T) are conserved. It is also sometimes called constant temperature molecular dynamics (CTMD). In NVT, the energy of endothermic and exothermic processes is exchanged with a thermostat.

A variety of thermostat algorithms are available to add and remove energy from the boundaries of an MD simulation in a more or less realistic way, approximating the canonical ensemble. Popular methods to control temperature include velocity rescaling, the Nosé–Hoover thermostat, Nosé–Hoover chains, the Berendsen thermostat, the Andersen thermostat and Langevin dynamics. The Berendsen thermostat might introduce the flying ice cube effect, which leads to unphysical translations and rotations of the simulated system.

It is not trivial to obtain a canonical ensemble distribution of conformations and velocities using these algorithms. How this depends on system size, thermostat choice, thermostat parameters, time step and integrator is the subject of many articles in the field.

Isothermal–isobaric (NPT) ensemble

In the isothermal–isobaric ensemble, amount of substance (N), pressure (P) and temperature (T) are conserved. In addition to a thermostat, a barostat is needed. It corresponds most closely to laboratory conditions with a flask open to ambient temperature and pressure.

In the simulation of biological membranes, isotropic pressure control is not appropriate. For lipid bilayers, pressure control occurs under constant membrane area (NPAT) or constant surface tension "gamma" (NPγT).

Generalized ensembles

The replica exchange method is a generalized ensemble. It was originally created to deal with the slow dynamics of disordered spin systems. It is also called parallel tempering. The replica exchange MD (REMD) formulation tries to overcome the multiple-minima problem by exchanging the temperature of non-interacting replicas of the system running at several temperatures.

Potentials in MD simulations

Main articles: Interatomic potential, Force field, and Comparison of force field implementationsA molecular dynamics simulation requires the definition of a potential function, or a description of the terms by which the particles in the simulation will interact. In chemistry and biology this is usually referred to as a force field and in materials physics as an interatomic potential. Potentials may be defined at many levels of physical accuracy; those most commonly used in chemistry are based on molecular mechanics and embody a classical mechanics treatment of particle-particle interactions that can reproduce structural and conformational changes but usually cannot reproduce chemical reactions.

The reduction from a fully quantum description to a classical potential entails two main approximations. The first one is the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, which states that the dynamics of electrons are so fast that they can be considered to react instantaneously to the motion of their nuclei. As a consequence, they may be treated separately. The second one treats the nuclei, which are much heavier than electrons, as point particles that follow classical Newtonian dynamics. In classical molecular dynamics, the effect of the electrons is approximated as one potential energy surface, usually representing the ground state.

When finer levels of detail are needed, potentials based on quantum mechanics are used; some methods attempt to create hybrid classical/quantum potentials where the bulk of the system is treated classically but a small region is treated as a quantum system, usually undergoing a chemical transformation.

Empirical potentials

Empirical potentials used in chemistry are frequently called force fields, while those used in materials physics are called interatomic potentials.

Most force fields in chemistry are empirical and consist of a summation of bonded forces associated with chemical bonds, bond angles, and bond dihedrals, and non-bonded forces associated with van der Waals forces and electrostatic charge. Empirical potentials represent quantum-mechanical effects in a limited way through ad hoc functional approximations. These potentials contain free parameters such as atomic charge, van der Waals parameters reflecting estimates of atomic radius, and equilibrium bond length, angle, and dihedral; these are obtained by fitting against detailed electronic calculations (quantum chemical simulations) or experimental physical properties such as elastic constants, lattice parameters and spectroscopic measurements.

Because of the non-local nature of non-bonded interactions, they involve at least weak interactions between all particles in the system. Its calculation is normally the bottleneck in the speed of MD simulations. To lower the computational cost, force fields employ numerical approximations such as shifted cutoff radii, reaction field algorithms, particle mesh Ewald summation, or the newer particle–particle-particle–mesh (P3M).

Chemistry force fields commonly employ preset bonding arrangements (an exception being ab initio dynamics), and thus are unable to model the process of chemical bond breaking and reactions explicitly. On the other hand, many of the potentials used in physics, such as those based on the bond order formalism can describe several different coordinations of a system and bond breaking. Examples of such potentials include the Brenner potential for hydrocarbons and its further developments for the C-Si-H and C-O-H systems. The ReaxFF potential can be considered a fully reactive hybrid between bond order potentials and chemistry force fields.

Pair potentials versus many-body potentials

The potential functions representing the non-bonded energy are formulated as a sum over interactions between the particles of the system. The simplest choice, employed in many popular force fields, is the "pair potential", in which the total potential energy can be calculated from the sum of energy contributions between pairs of atoms. Therefore, these force fields are also called "additive force fields". An example of such a pair potential is the non-bonded Lennard-Jones potential (also termed the 6–12 potential), used for calculating van der Waals forces.

Another example is the Born (ionic) model of the ionic lattice. The first term in the next equation is Coulomb's law for a pair of ions, the second term is the short-range repulsion explained by Pauli's exclusion principle and the final term is the dispersion interaction term. Usually, a simulation only includes the dipolar term, although sometimes the quadrupolar term is also included. When nl = 6, this potential is also called the Coulomb–Buckingham potential.

In many-body potentials, the potential energy includes the effects of three or more particles interacting with each other. In simulations with pairwise potentials, global interactions in the system also exist, but they occur only through pairwise terms. In many-body potentials, the potential energy cannot be found by a sum over pairs of atoms, as these interactions are calculated explicitly as a combination of higher-order terms. In the statistical view, the dependency between the variables cannot in general be expressed using only pairwise products of the degrees of freedom. For example, the Tersoff potential, which was originally used to simulate carbon, silicon, and germanium, and has since been used for a wide range of other materials, involves a sum over groups of three atoms, with the angles between the atoms being an important factor in the potential. Other examples are the embedded-atom method (EAM), the EDIP, and the Tight-Binding Second Moment Approximation (TBSMA) potentials, where the electron density of states in the region of an atom is calculated from a sum of contributions from surrounding atoms, and the potential energy contribution is then a function of this sum.

Semi-empirical potentials

Semi-empirical potentials make use of the matrix representation from quantum mechanics. However, the values of the matrix elements are found through empirical formulae that estimate the degree of overlap of specific atomic orbitals. The matrix is then diagonalized to determine the occupancy of the different atomic orbitals, and empirical formulae are used once again to determine the energy contributions of the orbitals.

There are a wide variety of semi-empirical potentials, termed tight-binding potentials, which vary according to the atoms being modeled.

Polarizable potentials

Main article: Force fieldMost classical force fields implicitly include the effect of polarizability, e.g., by scaling up the partial charges obtained from quantum chemical calculations. These partial charges are stationary with respect to the mass of the atom. But molecular dynamics simulations can explicitly model polarizability with the introduction of induced dipoles through different methods, such as Drude particles or fluctuating charges. This allows for a dynamic redistribution of charge between atoms which responds to the local chemical environment.

For many years, polarizable MD simulations have been touted as the next generation. For homogenous liquids such as water, increased accuracy has been achieved through the inclusion of polarizability. Some promising results have also been achieved for proteins. However, it is still uncertain how to best approximate polarizability in a simulation. The point becomes more important when a particle experiences different environments during its simulation trajectory, e.g. translocation of a drug through a cell membrane.

Potentials in ab initio methods

Main articles: Quantum chemistry and List of quantum chemistry and solid state physics softwareIn classical molecular dynamics, one potential energy surface (usually the ground state) is represented in the force field. This is a consequence of the Born–Oppenheimer approximation. In excited states, chemical reactions or when a more accurate representation is needed, electronic behavior can be obtained from first principles using a quantum mechanical method, such as density functional theory. This is named Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD). Due to the cost of treating the electronic degrees of freedom, the computational burden of these simulations is far higher than classical molecular dynamics. For this reason, AIMD is typically limited to smaller systems and shorter times.

Ab initio quantum mechanical and chemical methods may be used to calculate the potential energy of a system on the fly, as needed for conformations in a trajectory. This calculation is usually made in the close neighborhood of the reaction coordinate. Although various approximations may be used, these are based on theoretical considerations, not on empirical fitting. Ab initio calculations produce a vast amount of information that is not available from empirical methods, such as density of electronic states or other electronic properties. A significant advantage of using ab initio methods is the ability to study reactions that involve breaking or formation of covalent bonds, which correspond to multiple electronic states. Moreover, ab initio methods also allow recovering effects beyond the Born–Oppenheimer approximation using approaches like mixed quantum-classical dynamics.

Hybrid QM/MM

Main article: QM/MMQM (quantum-mechanical) methods are very powerful. However, they are computationally expensive, while the MM (classical or molecular mechanics) methods are fast but suffer from several limits (require extensive parameterization; energy estimates obtained are not very accurate; cannot be used to simulate reactions where covalent bonds are broken/formed; and are limited in their abilities for providing accurate details regarding the chemical environment). A new class of method has emerged that combines the good points of QM (accuracy) and MM (speed) calculations. These methods are termed mixed or hybrid quantum-mechanical and molecular mechanics methods (hybrid QM/MM).

The most important advantage of hybrid QM/MM method is the speed. The cost of doing classical molecular dynamics (MM) in the most straightforward case scales O(n), where n is the number of atoms in the system. This is mainly due to electrostatic interactions term (every particle interacts with every other particle). However, use of cutoff radius, periodic pair-list updates and more recently the variations of the particle-mesh Ewald's (PME) method has reduced this to between O(n) to O(n). In other words, if a system with twice as many atoms is simulated then it would take between two and four times as much computing power. On the other hand, the simplest ab initio calculations typically scale O(n) or worse (restricted Hartree–Fock calculations have been suggested to scale ~O(n)). To overcome the limit, a small part of the system is treated quantum-mechanically (typically active-site of an enzyme) and the remaining system is treated classically.

In more sophisticated implementations, QM/MM methods exist to treat both light nuclei susceptible to quantum effects (such as hydrogens) and electronic states. This allows generating hydrogen wave-functions (similar to electronic wave-functions). This methodology has been useful in investigating phenomena such as hydrogen tunneling. One example where QM/MM methods have provided new discoveries is the calculation of hydride transfer in the enzyme liver alcohol dehydrogenase. In this case, quantum tunneling is important for the hydrogen, as it determines the reaction rate.

Coarse-graining and reduced representations

At the other end of the detail scale are coarse-grained and lattice models. Instead of explicitly representing every atom of the system, one uses "pseudo-atoms" to represent groups of atoms. MD simulations on very large systems may require such large computer resources that they cannot easily be studied by traditional all-atom methods. Similarly, simulations of processes on long timescales (beyond about 1 microsecond) are prohibitively expensive, because they require so many time steps. In these cases, one can sometimes tackle the problem by using reduced representations, which are also called coarse-grained models.

Examples for coarse graining (CG) methods are discontinuous molecular dynamics (CG-DMD) and Go-models. Coarse-graining is done sometimes taking larger pseudo-atoms. Such united atom approximations have been used in MD simulations of biological membranes. Implementation of such approach on systems where electrical properties are of interest can be challenging owing to the difficulty of using a proper charge distribution on the pseudo-atoms. The aliphatic tails of lipids are represented by a few pseudo-atoms by gathering 2 to 4 methylene groups into each pseudo-atom.

The parameterization of these very coarse-grained models must be done empirically, by matching the behavior of the model to appropriate experimental data or all-atom simulations. Ideally, these parameters should account for both enthalpic and entropic contributions to free energy in an implicit way. When coarse-graining is done at higher levels, the accuracy of the dynamic description may be less reliable. But very coarse-grained models have been used successfully to examine a wide range of questions in structural biology, liquid crystal organization, and polymer glasses.

Examples of applications of coarse-graining:

- protein folding and protein structure prediction studies are often carried out using one, or a few, pseudo-atoms per amino acid;

- liquid crystal phase transitions have been examined in confined geometries and/or during flow using the Gay-Berne potential, which describes anisotropic species;

- Polymer glasses during deformation have been studied using simple harmonic or FENE springs to connect spheres described by the Lennard-Jones potential;

- DNA supercoiling has been investigated using 1–3 pseudo-atoms per basepair, and at even lower resolution;

- Packaging of double-helical DNA into bacteriophage has been investigated with models where one pseudo-atom represents one turn (about 10 basepairs) of the double helix;

- RNA structure in the ribosome and other large systems has been modeled with one pseudo-atom per nucleotide.

The simplest form of coarse-graining is the united atom (sometimes called extended atom) and was used in most early MD simulations of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. For example, instead of treating all four atoms of a CH3 methyl group explicitly (or all three atoms of CH2 methylene group), one represents the whole group with one pseudo-atom. It must, of course, be properly parameterized so that its van der Waals interactions with other groups have the proper distance-dependence. Similar considerations apply to the bonds, angles, and torsions in which the pseudo-atom participates. In this kind of united atom representation, one typically eliminates all explicit hydrogen atoms except those that have the capability to participate in hydrogen bonds (polar hydrogens). An example of this is the CHARMM 19 force-field.

The polar hydrogens are usually retained in the model, because proper treatment of hydrogen bonds requires a reasonably accurate description of the directionality and the electrostatic interactions between the donor and acceptor groups. A hydroxyl group, for example, can be both a hydrogen bond donor, and a hydrogen bond acceptor, and it would be impossible to treat this with one OH pseudo-atom. About half the atoms in a protein or nucleic acid are non-polar hydrogens, so the use of united atoms can provide a substantial savings in computer time.

Machine Learning Force Fields

Machine Learning Force Fields] (MLFFs) represent one approach to modeling interatomic interactions in molecular dynamics simulations. MLFFs can achieve accuracy close to that of ab initio methods. Once trained, MLFFs are much faster than direct quantum mechanical calculations. MLFFs address the limitations of traditional force fields by learning complex potential energy surfaces directly from high-level quantum mechanical data. Several software packages now support MLFFs, including VASP and open-source libraries like DeePMD-kit and SchNetPack.

Incorporating solvent effects

In many simulations of a solute-solvent system the main focus is on the behavior of the solute with little interest of the solvent behavior particularly in those solvent molecules residing in regions far from the solute molecule. Solvents may influence the dynamic behavior of solutes via random collisions and by imposing a frictional drag on the motion of the solute through the solvent. The use of non-rectangular periodic boundary conditions, stochastic boundaries and solvent shells can all help reduce the number of solvent molecules required and enable a larger proportion of the computing time to be spent instead on simulating the solute. It is also possible to incorporate the effects of a solvent without needing any explicit solvent molecules present. One example of this approach is to use a potential mean force (PMF) which describes how the free energy changes as a particular coordinate is varied. The free energy change described by PMF contains the averaged effects of the solvent.

Without incorporating the effects of solvent simulations of macromolecules (such as proteins) may yield unrealistic behavior and even small molecules may adopt more compact conformations due to favourable van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions which would be dampened in the presence of a solvent.

Long-range forces

A long range interaction is an interaction in which the spatial interaction falls off no faster than where is the dimensionality of the system. Examples include charge-charge interactions between ions and dipole-dipole interactions between molecules. Modelling these forces presents quite a challenge as they are significant over a distance which may be larger than half the box length with simulations of many thousands of particles. Though one solution would be to significantly increase the size of the box length, this brute force approach is less than ideal as the simulation would become computationally very expensive. Spherically truncating the potential is also out of the question as unrealistic behaviour may be observed when the distance is close to the cut off distance.

Steered molecular dynamics (SMD)

Steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations, or force probe simulations, apply forces to a protein in order to manipulate its structure by pulling it along desired degrees of freedom. These experiments can be used to reveal structural changes in a protein at the atomic level. SMD is often used to simulate events such as mechanical unfolding or stretching.

There are two typical protocols of SMD: one in which pulling velocity is held constant, and one in which applied force is constant. Typically, part of the studied system (e.g., an atom in a protein) is restrained by a harmonic potential. Forces are then applied to specific atoms at either a constant velocity or a constant force. Umbrella sampling is used to move the system along the desired reaction coordinate by varying, for example, the forces, distances, and angles manipulated in the simulation. Through umbrella sampling, all of the system's configurations—both high-energy and low-energy—are adequately sampled. Then, each configuration's change in free energy can be calculated as the potential of mean force. A popular method of computing PMF is through the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM), which analyzes a series of umbrella sampling simulations.

A lot of important applications of SMD are in the field of drug discovery and biomolecular sciences. For e.g. SMD was used to investigate the stability of Alzheimer's protofibrils, to study the protein ligand interaction in cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and even to show the effect of electric field on thrombin (protein) and aptamer (nucleotide) complex among many other interesting studies.

Examples of applications

| This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Molecular dynamics" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Molecular dynamics is used in many fields of science.

- First MD simulation of a simplified biological folding process was published in 1975. Its simulation published in Nature paved the way for the vast area of modern computational protein-folding.

- First MD simulation of a biological process was published in 1976. Its simulation published in Nature paved the way for understanding protein motion as essential in function and not just accessory.

- MD is the standard method to treat collision cascades in the heat spike regime, i.e., the effects that energetic neutron and ion irradiation have on solids and solid surfaces.

The following biophysical examples illustrate notable efforts to produce simulations of a systems of very large size (a complete virus) or very long simulation times (up to 1.112 milliseconds):

- MD simulation of the full satellite tobacco mosaic virus (STMV) (2006, Size: 1 million atoms, Simulation time: 50 ns, program: NAMD) This virus is a small, icosahedral plant virus that worsens the symptoms of infection by Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV). Molecular dynamics simulations were used to probe the mechanisms of viral assembly. The entire STMV particle consists of 60 identical copies of one protein that make up the viral capsid (coating), and a 1063 nucleotide single stranded RNA genome. One key finding is that the capsid is very unstable when there is no RNA inside. The simulation would take one 2006 desktop computer around 35 years to complete. It was thus done in many processors in parallel with continuous communication between them.

- Folding simulations of the Villin Headpiece in all-atom detail (2006, Size: 20,000 atoms; Simulation time: 500 μs= 500,000 ns, Program: Folding@home) This simulation was run in 200,000 CPU's of participating personal computers around the world. These computers had the Folding@home program installed, a large-scale distributed computing effort coordinated by Vijay Pande at Stanford University. The kinetic properties of the Villin Headpiece protein were probed by using many independent, short trajectories run by CPU's without continuous real-time communication. One method employed was the Pfold value analysis, which measures the probability of folding before unfolding of a specific starting conformation. Pfold gives information about transition state structures and an ordering of conformations along the folding pathway. Each trajectory in a Pfold calculation can be relatively short, but many independent trajectories are needed.

- Long continuous-trajectory simulations have been performed on Anton, a massively parallel supercomputer designed and built around custom application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) and interconnects by D. E. Shaw Research. The longest published result of a simulation performed using Anton is a 1.112-millisecond simulation of NTL9 at 355 K; a second, independent 1.073-millisecond simulation of this configuration was also performed (and many other simulations of over 250 μs continuous chemical time). In How Fast-Folding Proteins Fold, researchers Kresten Lindorff-Larsen, Stefano Piana, Ron O. Dror, and David E. Shaw discuss "the results of atomic-level molecular dynamics simulations, over periods ranging between 100 μs and 1 ms, that reveal a set of common principles underlying the folding of 12 structurally diverse proteins." Examination of these diverse long trajectories, enabled by specialized, custom hardware, allow them to conclude that "In most cases, folding follows a single dominant route in which elements of the native structure appear in an order highly correlated with their propensity to form in the unfolded state." In a separate study, Anton was used to conduct a 1.013-millisecond simulation of the native-state dynamics of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI) at 300 K.

Another important application of MD method benefits from its ability of 3-dimensional characterization and analysis of microstructural evolution at atomic scale.

- MD simulations are used in characterization of grain size evolution, for example, when describing wear and friction of nanocrystalline Al and Al(Zr) materials. Dislocations evolution and grain size evolution are analyzed during the friction process in this simulation. Since MD method provided the full information of the microstructure, the grain size evolution was calculated in 3D using the Polyhedral Template Matching, Grain Segmentation, and Graph clustering methods. In such simulation, MD method provided an accurate measurement of grain size. Making use of these information, the actual grain structures were extracted, measured, and presented. Compared to the traditional method of using SEM with a single 2-dimensional slice of the material, MD provides a 3-dimensional and accurate way to characterize the microstructural evolution at atomic scale.

Molecular dynamics algorithms

Integrators

- Symplectic integrator

- Verlet–Stoermer integration

- Runge–Kutta integration

- Beeman's algorithm

- Constraint algorithms (for constrained systems)

Short-range interaction algorithms

- Cell lists

- Verlet list

- Bonded interactions

Long-range interaction algorithms

- Ewald summation

- Particle mesh Ewald summation (PME)

- Particle–particle-particle–mesh (P3M)

- Shifted force method

Parallelization strategies

- Domain decomposition method (Distribution of system data for parallel computing)

Ab-initio molecular dynamics

Specialized hardware for MD simulations

- Anton – A specialized, massively parallel supercomputer designed to execute MD simulations

- MDGRAPE – A special purpose system built for molecular dynamics simulations, especially protein structure prediction

Graphics card as a hardware for MD simulations

This section is an excerpt from Molecular modeling on GPUs.

Molecular modeling on GPU is the technique of using a graphics processing unit (GPU) for molecular simulations.

In 2007, Nvidia introduced video cards that could be used not only to show graphics but also for scientific calculations. These cards include many arithmetic units (as of 2016, up to 3,584 in Tesla P100) working in parallel. Long before this event, the computational power of video cards was purely used to accelerate graphics calculations. What was new is that Nvidia made it possible to develop parallel programs in a high-level application programming interface (API) named CUDA. This technology substantially simplified programming by enabling programs to be written in C/C++. More recently, OpenCL allows cross-platform GPU acceleration.See also

- Molecular modeling

- Computational chemistry

- Force field (chemistry)

- Comparison of force field implementations

- Monte Carlo method

- Molecular design software

- Molecular mechanics

- Multiscale Green's function

- Car–Parrinello method

- Comparison of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Quantum chemistry

- Discrete element method

- Comparison of nucleic acid simulation software

- Molecule editor

- Mixed quantum-classical dynamics

References

- Schlick T (1996). "Pursuing Laplace's Vision on Modern Computers". Mathematical Approaches to Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. The IMA Volumes in Mathematics and its Applications. Vol. 82. pp. 219–247. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4066-2_13. ISBN 978-0-387-94838-6.

- Bernal JD (January 1997). "The Bakerian Lecture, 1962 The structure of liquids". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 280 (1382): 299–322. Bibcode:1964RSPSA.280..299B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1964.0147. S2CID 178710030.

- Fermi E., Pasta J., Ulam S., Los Alamos report LA-1940 (1955).

- Alder BJ, Wainwright T (August 1959). "Studies in Molecular Dynamics. I. General Method". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 31 (2): 459–466. Bibcode:1959JChPh..31..459A. doi:10.1063/1.1730376.

- Gibson JB, Goland AN, Milgram M, Vineyard G (1960). "Dynamics of Radiation Damage". Phys. Rev. 120 (4): 1229–1253. Bibcode:1960PhRv..120.1229G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.120.1229.

- Rahman A (19 October 1964). "Correlations in the Motion of Atoms in Liquid Argon". Physical Review. 136 (2A): A405 – A411. Bibcode:1964PhRv..136..405R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.136.A405.

- Stephan S, Thol M, Vrabec J, Hasse H (October 2019). "Thermophysical Properties of the Lennard-Jones Fluid: Database and Data Assessment". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 59 (10): 4248–4265. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00620. PMID 31609113. S2CID 204545481.

- Wang X, Ramírez-Hinestrosa S, Dobnikar J, Frenkel D (May 2020). "The Lennard-Jones potential: when (not) to use it". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 22 (19): 10624–10633. arXiv:1910.05746. Bibcode:2020PCCP...2210624W. doi:10.1039/C9CP05445F. PMID 31681941. S2CID 204512243.

- Mick J, Hailat E, Russo V, Rushaidat K, Schwiebert L, Potoff J (December 2013). "GPU-accelerated Gibbs ensemble Monte Carlo simulations of Lennard-Jonesium". Computer Physics Communications. 184 (12): 2662–2669. Bibcode:2013CoPhC.184.2662M. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2013.06.020.

- Chapela GA, Scriven LE, Davis HT (October 1989). "Molecular dynamics for discontinuous potential. IV. Lennard-Jonesium". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 91 (7): 4307–4313. Bibcode:1989JChPh..91.4307C. doi:10.1063/1.456811. ISSN 0021-9606.

- Lenhard J, Stephan S, Hasse H (February 2024). "A child of prediction. On the History, Ontology, and Computation of the Lennard-Jonesium". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. 103: 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2023.11.007. PMID 38128443. S2CID 266440296.

- Eggimann BL, Sunnarborg AJ, Stern HD, Bliss AP, Siepmann JI (2013-12-24). "An online parameter and property database for the TraPPE force field". Molecular Simulation. 40 (1–3): 101–105. doi:10.1080/08927022.2013.842994. ISSN 0892-7022. S2CID 95716947.

- Stephan S, Horsch MT, Vrabec J, Hasse H (2019-07-03). "MolMod – an open access database of force fields for molecular simulations of fluids". Molecular Simulation. 45 (10): 806–814. arXiv:1904.05206. doi:10.1080/08927022.2019.1601191. ISSN 0892-7022. S2CID 119199372.

- Koehl P, Levitt M (February 1999). "A brighter future for protein structure prediction". Nature Structural Biology. 6 (2): 108–111. doi:10.1038/5794. PMID 10048917. S2CID 3162636.

- Raval A, Piana S, Eastwood MP, Dror RO, Shaw DE (August 2012). "Refinement of protein structure homology models via long, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations". Proteins. 80 (8): 2071–2079. doi:10.1002/prot.24098. PMID 22513870. S2CID 10613106.

- Beauchamp KA, Lin YS, Das R, Pande VS (April 2012). "Are Protein Force Fields Getting Better? A Systematic Benchmark on 524 Diverse NMR Measurements". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 8 (4): 1409–1414. doi:10.1021/ct2007814. PMC 3383641. PMID 22754404.

- Piana S, Klepeis JL, Shaw DE (February 2014). "Assessing the accuracy of physical models used in protein-folding simulations: quantitative evidence from long molecular dynamics simulations". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 24: 98–105. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2013.12.006. PMID 24463371.

- Choudhury C, Priyakumar UD, Sastry GN (April 2015). "Dynamics based pharmacophore models for screening potential inhibitors of mycobacterial cyclopropane synthase". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 55 (4): 848–60. doi:10.1021/ci500737b. PMID 25751016.

- Pinto M, Perez JJ, Rubio-Martinez J (January 2004). "Molecular dynamics study of peptide segments of the BH3 domain of the proapoptotic proteins Bak, Bax, Bid and Hrk bound to the Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 proteins". Journal of Computer-aided Molecular Design. 18 (1): 13–22. Bibcode:2004JCAMD..18...13P. doi:10.1023/b:jcam.0000022559.72848.1c. PMID 15143800. S2CID 11339000.

- Hatmal MM, Jaber S, Taha MO (December 2016). "Combining molecular dynamics simulation and ligand-receptor contacts analysis as a new approach for pharmacophore modeling: beta-secretase 1 and check point kinase 1 as case studies". Journal of Computer-aided Molecular Design. 30 (12): 1149–1163. Bibcode:2016JCAMD..30.1149H. doi:10.1007/s10822-016-9984-2. PMID 27722817. S2CID 11561853.

- Myers JK, Pace CN (October 1996). "Hydrogen bonding stabilizes globular proteins". Biophysical Journal. 71 (4): 2033–2039. Bibcode:1996BpJ....71.2033M. doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(96)79401-8. PMC 1233669. PMID 8889177.

- Lenhard J, Stephan S, Hasse H (June 2024). "On the History of the Lennard-Jones Potential". Annalen der Physik. 536 (6). doi:10.1002/andp.202400115. ISSN 0003-3804.

- Fischer J, Wendland M (October 2023). "On the history of key empirical intermolecular potentials". Fluid Phase Equilibria. 573: 113876. Bibcode:2023FlPEq.57313876F. doi:10.1016/j.fluid.2023.113876.

- ^ Israelachvili J (1992). Intermolecular and surface forces. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Cruz FJ, de Pablo JJ, Mota JP (June 2014). "Endohedral confinement of a DNA dodecamer onto pristine carbon nanotubes and the stability of the canonical B form". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 140 (22): 225103. arXiv:1605.01317. Bibcode:2014JChPh.140v5103C. doi:10.1063/1.4881422. PMID 24929415. S2CID 15149133.

- Cruz FJ, Mota JP (2016). "Conformational Thermodynamics of DNA Strands in Hydrophilic Nanopores". J. Phys. Chem. C. 120 (36): 20357–20367. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b06234.

- Plimpton S. "Molecular Dynamics - Parallel Algorithms". sandia.gov.

- Streett WB, Tildesley DJ, Saville G (1978). "Multiple time-step methods in molecular dynamics". Mol Phys. 35 (3): 639–648. Bibcode:1978MolPh..35..639S. doi:10.1080/00268977800100471.

- Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ, Martyna GJ (1991). "Molecular dynamics algorithm for multiple time scales: systems with long range forces". J Chem Phys. 94 (10): 6811–6815. Bibcode:1991JChPh..94.6811T. doi:10.1063/1.460259.

- Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ, Martyna GJ (1992). "Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics". J Chem Phys. 97 (3): 1990–2001. Bibcode:1992JChPh..97.1990T. doi:10.1063/1.463137. S2CID 488073.

- Sugita Y, Okamoto Y (November 1999). "Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding". Chemical Physics Letters. 314 (1–2): 141–151. Bibcode:1999CPL...314..141S. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01123-9.

- Rizzuti B (2022). "Molecular simulations of proteins: From simplified physical interactions to complex biological phenomena". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1870 (3): 140757. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2022.140757. PMID 35051666. S2CID 263455009.

- Sinnott SB, Brenner DW (2012). "Three decades of many-body potentials in materials research". MRS Bulletin. 37 (5): 469–473. Bibcode:2012MRSBu..37..469S. doi:10.1557/mrs.2012.88.

- Albe K, Nordlund K, Averback RS (2002). "Modeling metal-semiconductor interaction: Analytical bond-order potential for platinum-carbon". Phys. Rev. B. 65 (19): 195124. Bibcode:2002PhRvB..65s5124A. doi:10.1103/physrevb.65.195124.

- Brenner DW (November 1990). "Empirical potential for hydrocarbons for use in simulating the chemical vapor deposition of diamond films" (PDF). Physical Review B. 42 (15): 9458–9471. Bibcode:1990PhRvB..42.9458B. doi:10.1103/physrevb.42.9458. PMID 9995183. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017.

- Beardmore K, Smith R (1996). "Empirical potentials for C-Si-H systems with application to C60 interactions with Si crystal surfaces". Philosophical Magazine A. 74 (6): 1439–1466. Bibcode:1996PMagA..74.1439B. doi:10.1080/01418619608240734.

- Ni B, Lee KH, Sinnott SB (2004). "A reactive empirical bond order (rebo) potential for hydrocarbon oxygen interactions". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 16 (41): 7261–7275. Bibcode:2004JPCM...16.7261N. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/16/41/008. S2CID 250760409.

- Van Duin AC, Dasgupta S, Lorant F, Goddard WA (October 2001). "ReaxFF: A Reactive Force Field for Hydrocarbons". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 105 (41): 9396–9409. Bibcode:2001JPCA..105.9396V. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.507.6992. doi:10.1021/jp004368u.

- Cruz FJ, Lopes JN, Calado JC, Minas da Piedade ME (December 2005). "A molecular dynamics study of the thermodynamic properties of calcium apatites. 1. Hexagonal phases". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 109 (51): 24473–24479. doi:10.1021/jp054304p. PMID 16375450.

- Cruz FJ, Lopes JN, Calado JC (March 2006). "Molecular dynamics simulations of molten calcium hydroxyapatite". Fluid Phase Equilibria. 241 (1–2): 51–58. Bibcode:2006FlPEq.241...51C. doi:10.1016/j.fluid.2005.12.021.

- ^ Justo JF, Bazant MZ, Kaxiras E, Bulatov VV, Yip S (1998). "Interatomic potential for silicon defects and disordered phases". Phys. Rev. B. 58 (5): 2539–2550. arXiv:cond-mat/9712058. Bibcode:1998PhRvB..58.2539J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.58.2539. S2CID 14585375.

- Tersoff J (March 1989). "Modeling solid-state chemistry: Interatomic potentials for multicomponent systems". Physical Review B. 39 (8): 5566–5568. Bibcode:1989PhRvB..39.5566T. doi:10.1103/physrevb.39.5566. PMID 9948964.

- Daw MS, Foiles SM, Baskes MI (March 1993). "The embedded-atom method: a review of theory and applications". Materials Science Reports. 9 (7–8): 251–310. doi:10.1016/0920-2307(93)90001-U.

- Cleri F, Rosato V (July 1993). "Tight-binding potentials for transition metals and alloys". Physical Review B. 48 (1): 22–33. Bibcode:1993PhRvB..48...22C. doi:10.1103/physrevb.48.22. PMID 10006745.

- Lamoureux G, Harder E, Vorobyov IV, Roux B, MacKerell AD (2006). "A polarizable model of water for molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules". Chem Phys Lett. 418 (1): 245–249. Bibcode:2006CPL...418..245L. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2005.10.135.

- Sokhan VP, Jones AP, Cipcigan FS, Crain J, Martyna GJ (May 2015). "Signature properties of water: Their molecular electronic origins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (20): 6341–6346. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.6341S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418982112. PMC 4443379. PMID 25941394.

- Cipcigan FS, Sokhan VP, Jones AP, Crain J, Martyna GJ (April 2015). "Hydrogen bonding and molecular orientation at the liquid-vapour interface of water". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 17 (14): 8660–8669. Bibcode:2015PCCP...17.8660C. doi:10.1039/C4CP05506C. hdl:20.500.11820/0bd0cd1a-94f1-4053-809c-9fb68bbec1c9. PMID 25715668.

- Mahmoudi M, Lynch I, Ejtehadi MR, Monopoli MP, Bombelli FB, Laurent S (September 2011). "Protein-nanoparticle interactions: opportunities and challenges". Chemical Reviews. 111 (9): 5610–5637. doi:10.1021/cr100440g. PMID 21688848.

- Patel S, Mackerell AD, Brooks CL (September 2004). "CHARMM fluctuating charge force field for proteins: II protein/solvent properties from molecular dynamics simulations using a nonadditive electrostatic model". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 25 (12): 1504–1514. doi:10.1002/jcc.20077. PMID 15224394. S2CID 16741310.

- Najla Hosseini A, Lund M, Ejtehadi MR (May 2022). "Electronic polarization effects on membrane translocation of anti-cancer drugs". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 24 (20): 12281–12292. Bibcode:2022PCCP...2412281N. doi:10.1039/D2CP00056C. PMID 35543365. S2CID 248696332.

- The methodology for such methods was introduced by Warshel and coworkers. In the recent years have been pioneered by several groups including: Arieh Warshel (University of Southern California), Weitao Yang (Duke University), Sharon Hammes-Schiffer (The Pennsylvania State University), Donald Truhlar and Jiali Gao (University of Minnesota) and Kenneth Merz (University of Florida).

- Billeter SR, Webb SP, Agarwal PK, Iordanov T, Hammes-Schiffer S (November 2001). "Hydride transfer in liver alcohol dehydrogenase: quantum dynamics, kinetic isotope effects, and role of enzyme motion". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 123 (45): 11262–11272. doi:10.1021/ja011384b. PMID 11697969.

- ^ Kmiecik S, Gront D, Kolinski M, Wieteska L, Dawid AE, Kolinski A (July 2016). "Coarse-Grained Protein Models and Their Applications". Chemical Reviews. 116 (14): 7898–7936. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00163. PMID 27333362.

- Voegler Smith A, Hall CK (August 2001). "alpha-helix formation: discontinuous molecular dynamics on an intermediate-resolution protein model". Proteins. 44 (3): 344–360. doi:10.1002/prot.1100. PMID 11455608. S2CID 21774752.

- Ding F, Borreguero JM, Buldyrey SV, Stanley HE, Dokholyan NV (November 2003). "Mechanism for the alpha-helix to beta-hairpin transition". Proteins. 53 (2): 220–228. doi:10.1002/prot.10468. PMID 14517973. S2CID 17254380.

- Paci E, Vendruscolo M, Karplus M (December 2002). "Validity of Gō models: comparison with a solvent-shielded empirical energy decomposition". Biophysical Journal. 83 (6): 3032–3038. Bibcode:2002BpJ....83.3032P. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75308-3. PMC 1302383. PMID 12496075.

- Chakrabarty A, Cagin T (May 2010). "Coarse grain modeling of polyimide copolymers". Polymer. 51 (12): 2786–2794. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2010.03.060.

- Foley TT, Shell MS, Noid WG (December 2015). "The impact of resolution upon entropy and information in coarse-grained models". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 143 (24): 243104. Bibcode:2015JChPh.143x3104F. doi:10.1063/1.4929836. PMID 26723589.

- Unke OT, Chmiela S, Sauceda HE, Gastegger M, Poltavsky I, Schütt KT, et al. (August 2021). "Machine Learning Force Fields". Chemical Reviews. 121 (16): 10142–10186. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01111. PMC 8391964. PMID 33705118.

- Hafner J (October 2008). "Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 29 (13): 2044–78. doi:10.1002/jcc.21057. PMID 18623101.

- Wang H, Zhang L, Han J, Weinan E (July 2018). "DeePMD-kit: A deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics". Computer Physics Communications. 228: 178–184. arXiv:1712.03641. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2018.03.016.

- Zeng J, Zhang D, Lu D, Mo P, Li Z, Chen Y, et al. (August 2023). "DeePMD-kit v2: A software package for deep potential models". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 159 (5). doi:10.1063/5.0155600. PMC 10445636. PMID 37526163.

- Schütt KT, Kessel P, Gastegger M, Nicoli KA, Tkatchenko A, Müller KR (January 2019). "SchNetPack: A Deep Learning Toolbox For Atomistic Systems". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 15 (1): 448–455. arXiv:1809.01072. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00908. PMID 30481453.

- Schütt KT, Hessmann SS, Gebauer NW, Lederer J, Gastegger M (April 2023). "SchNetPack 2.0: A neural network toolbox for atomistic machine learning". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 158 (14): 144801. arXiv:2212.05517. doi:10.1063/5.0138367.

- Leach A (30 January 2001). Molecular Modelling: Principles and Applications (2nd ed.). Harlow: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780582382107. ASIN 0582382106.

- Leach AR (2001). Molecular modelling : principles and applications (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Prentice Hall. p. 320. ISBN 0-582-38210-6. OCLC 45008511.

- Allen MP, Tildesley DJ (2017-08-22). Computer Simulation of Liquids (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 216. ISBN 9780198803201. ASIN 0198803206.

- Nienhaus GU (2005). Protein-ligand interactions: methods and applications. Humana Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-1-61737-525-5.

- Leszczyński J (2005). Computational chemistry: reviews of current trends, Volume 9. World Scientific. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-981-256-742-0.

- Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA (October 1992). "The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 13 (8): 1011–1021. doi:10.1002/jcc.540130812. S2CID 8571486.

- Bartels C (December 2000). "Analyzing biased Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations". Chemical Physics Letters. 331 (5–6): 446–454. Bibcode:2000CPL...331..446B. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(00)01215-X.

- Lemkul JA, Bevan DR (February 2010). "Assessing the stability of Alzheimer's amyloid protofibrils using molecular dynamics". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 114 (4): 1652–1660. doi:10.1021/jp9110794. PMID 20055378.

- Patel JS, Berteotti A, Ronsisvalle S, Rocchia W, Cavalli A (February 2014). "Steered molecular dynamics simulations for studying protein-ligand interaction in cyclin-dependent kinase 5". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 54 (2): 470–480. doi:10.1021/ci4003574. PMID 24437446.

- Gosai A, Ma X, Balasubramanian G, Shrotriya P (November 2016). "Electrical Stimulus Controlled Binding/Unbinding of Human Thrombin-Aptamer Complex". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 37449. Bibcode:2016NatSR...637449G. doi:10.1038/srep37449. PMC 5118750. PMID 27874042.

- Palma CA, Björk J, Rao F, Kühne D, Klappenberger F, Barth JV (August 2014). "Topological dynamics in supramolecular rotors". Nano Letters. 14 (8): 4461–4468. Bibcode:2014NanoL..14.4461P. doi:10.1021/nl5014162. PMID 25078022.

- Levitt M, Warshel A (February 1975). "Computer simulation of protein folding". Nature. 253 (5494): 694–698. Bibcode:1975Natur.253..694L. doi:10.1038/253694a0. PMID 1167625. S2CID 4211714.

- Warshel A (April 1976). "Bicycle-pedal model for the first step in the vision process". Nature. 260 (5553): 679–683. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..679W. doi:10.1038/260679a0. PMID 1264239. S2CID 4161081.

- Smith, R., ed. (1997). Atomic & ion collisions in solids and at surfaces: theory, simulation and applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Freddolino P, Arkhipov A, Larson SB, McPherson A, Schulten K. "Molecular dynamics simulation of the Satellite Tobacco Mosaic Virus (STMV)". Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group. University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign.

- Jayachandran G, Vishal V, Pande VS (April 2006). "Using massively parallel simulation and Markovian models to study protein folding: examining the dynamics of the villin headpiece". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 124 (16): 164902. Bibcode:2006JChPh.124p4902J. doi:10.1063/1.2186317. PMID 16674165.

- ^ Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Dror RO, Shaw DE (October 2011). "How fast-folding proteins fold". Science. 334 (6055): 517–520. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..517L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.9290. doi:10.1126/science.1208351. PMID 22034434. S2CID 27988268.

- Shaw DE, Maragakis P, Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, et al. (October 2010). "Atomic-level characterization of the structural dynamics of proteins". Science. 330 (6002): 341–346. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..341S. doi:10.1126/science.1187409. PMID 20947758. S2CID 3495023.

- Shi Y, Szlufarska I (November 2020). "Wear-induced microstructural evolution of nanocrystalline aluminum and the role of zirconium dopants". Acta Materialia. 200: 432–441. Bibcode:2020AcMat.200..432S. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2020.09.005. S2CID 224954349.

- Larsen PM, Schmidt S, Schiøtz J (1 June 2016). "Robust structural identification via polyhedral template matching". Modelling and Simulation in Materials Science and Engineering. 24 (5): 055007. arXiv:1603.05143. Bibcode:2016MSMSE..24e5007M. doi:10.1088/0965-0393/24/5/055007. S2CID 53980652.

- Hoffrogge PW, Barrales-Mora LA (February 2017). "Grain-resolved kinetics and rotation during grain growth of nanocrystalline Aluminium by molecular dynamics". Computational Materials Science. 128: 207–222. arXiv:1608.07615. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2016.11.027. S2CID 118371554.

- Bonald T, Charpentier B, Galland A, Hollocou A (22 June 2018). "Hierarchical Graph Clustering using Node Pair Sampling". arXiv:1806.01664 .

- Stone JE, Phillips JC, Freddolino PL, Hardy DJ, Trabuco LG, Schulten K (December 2007). "Accelerating molecular modeling applications with graphics processors". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 28 (16): 2618–2640. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.3823. doi:10.1002/jcc.20829. PMID 17894371. S2CID 15313533.

General references

- Allen MP, Tildesley DJ (1989). Computer simulation of liquids. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855645-4.

- McCammon JA, Harvey SC (1987). Dynamics of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30750-3.

- Rapaport DC (1996). The Art of Molecular Dynamics Simulation. ISBN 0-521-44561-2.

- Griebel M, Knapek S, Zumbusch G (2007). Numerical Simulation in Molecular Dynamics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-68094-9.

- Frenkel D, Smit B (2002) . Understanding Molecular Simulation : from algorithms to applications. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-267351-1.

- Haile JM (2001). Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Elementary Methods. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-18439-X.

- Sadus RJ (2002). Molecular Simulation of Fluids: Theory, Algorithms and Object-Orientation. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-51082-6.

- Becker OM, Mackerell Jr AD, Roux B, Watanabe M (2001). Computational Biochemistry and Biophysics. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-0455-X.

- Leach A (2001). Molecular Modelling: Principles and Applications (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-582-38210-7.

- Schlick T (2002). Molecular Modeling and Simulation. Springer. ISBN 0-387-95404-X.

- Hoover WB (1991). Computational Statistical Mechanics. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-88192-1.

- Evans DJ, Morriss G (2008). Statistical Mechanics of Nonequilibrium Liquids (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85791-8.

External links

- The GPUGRID.net Project (GPUGRID.net)

- The Blue Gene Project (IBM) JawBreakers.org

- Materials modelling and computer simulation codes

- A few tips on molecular dynamics

- Movie of MD simulation of water (YouTube)

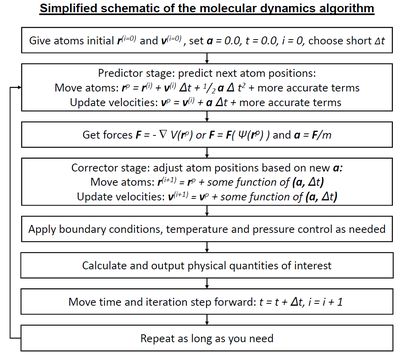

) or quantum mechanical (described mathematically as

) or quantum mechanical (described mathematically as  ) methods. Large differences exist between different integrators; some do not have exactly the same highest-order terms as indicated in the flow chart, many also use higher-order time derivatives, and some use both the current and prior time step in variable-time step schemes.

) methods. Large differences exist between different integrators; some do not have exactly the same highest-order terms as indicated in the flow chart, many also use higher-order time derivatives, and some use both the current and prior time step in variable-time step schemes. if all pair-wise

if all pair-wise  ), particle-particle-particle mesh (

), particle-particle-particle mesh ( ).

).

and velocities

and velocities  , the following pair of first order differential equations may be written in

, the following pair of first order differential equations may be written in

of the system is a function of the particle coordinates

of the system is a function of the particle coordinates  acting on each particle in the system can be calculated as the negative gradient of

acting on each particle in the system can be calculated as the negative gradient of  or more) with no big change in temperature. When there are only 500 atoms, however, the substrate is almost immediately vaporized by the deposition. Something similar happens in biophysical simulations. The temperature of the system in NVE is naturally raised when macromolecules such as proteins undergo exothermic conformational changes and binding.

or more) with no big change in temperature. When there are only 500 atoms, however, the substrate is almost immediately vaporized by the deposition. Something similar happens in biophysical simulations. The temperature of the system in NVE is naturally raised when macromolecules such as proteins undergo exothermic conformational changes and binding.

where

where  is the dimensionality of the system. Examples include charge-charge interactions between ions and dipole-dipole interactions between molecules. Modelling these forces presents quite a challenge as they are significant over a distance which may be larger than half the box length with simulations of many thousands of particles. Though one solution would be to significantly increase the size of the box length, this brute force approach is less than ideal as the simulation would become computationally very expensive. Spherically truncating the potential is also out of the question as unrealistic behaviour may be observed when the distance is close to the cut off distance.

is the dimensionality of the system. Examples include charge-charge interactions between ions and dipole-dipole interactions between molecules. Modelling these forces presents quite a challenge as they are significant over a distance which may be larger than half the box length with simulations of many thousands of particles. Though one solution would be to significantly increase the size of the box length, this brute force approach is less than ideal as the simulation would become computationally very expensive. Spherically truncating the potential is also out of the question as unrealistic behaviour may be observed when the distance is close to the cut off distance.