| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Bermuda Militia" 1612–1687 – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Between 1612 and 1687, Bermuda had a series of militias under the Virginia Company, the Somers Isles Company, and the British Crown. In 1687, the first Militia Act was enacted.

Spain had claimed the entirety of the New World, including Bermuda, for itself, and, notwithstanding the Pope's dividing South America between it and Portugal, it ruthlessly sought to prevent other European nations, especially England, establishing a foothold, even in, North America which the Spanish had largely avoided themselves. England's first two attempts at settling the Chesapeake had come under threat from Spanish forces ordered out from Florida to destroy them. What fate ultimately befell those two colonies is unclear, but the third established, Jamestown, spent its first years teetering on the same knife-edge between the threats of the Spanish, the Native nations, starvation, and disease.

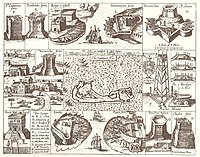

Bermuda, also, was subject to Spanish threat. Colonised by the Virginia Company, accidentally, in 1609, the first settlers arrived under Governor Richard Moore in 1612. Moore's first concern was the defence of the colony against an attack that was thought imminent. He oversaw the start of the fortifications built around Castle Harbour and the Town of St. George's.

A militia was raised to man the artillery in these fortifications. The majority of the settlers were indentured - tenant farmers, who would hand most of their produce to the company in exchange for the cost of their transportation to Bermuda. The company reduced by a quarter the payments to be made by those settlers who volunteered for the militia.

Although Spain never acted on its threat to destroy the English settlement, a Spanish vessel did arrive off of Castle Harbour, not long after settlement. The vessel turned and fled after the firing of warning shots by the militia. According to popular accounts, the warning shots had left only enough powder for one more shot.

Under Moore's replacement, Governor Nathaniel Butler, 1619–1622, the detachment at each of the forts was re-organized to include several militia men under a trained artillery captain. Also, each of the parishes was responsible to raise a company of volunteers, and to build a store-house for weapons and grain. Each militia man was provided with a sword and a musket, with all of the muskets required to be of a common bore.

The end of Butler's Governorship coincided with the Virginia Company's loss of its Royal Charter for the administration of Virginia (North America). The company was dissolved in 1624, and The Crown assumed its responsibilities for the continental settlement. Bermuda, or the Somers Isles, to use the Colony's other official name, however had been administered by a separate company, formed by the same share-holders, since 1615. Titled The Somers Isles Company, it continued to operate Bermuda as a commercial venture until it, too, was dissolved by King Charles II in 1684.

This had profound effects on Bermuda, allowing the colony to abandon agriculture entirely, and turn to shipbuilding and seafaring. This included the development of Bermudian effective-suzerainty in the Turks and Caicos, where the salt industry became a key component of the economy, and where Bermudians would launch their first, independent military expedition. The dissolution of the company also meant the end of the system of indentured servitude, which had ensured a cheap labour pool, preventing slavery becoming the basis of the economy, as it had in other agricultural colonies. At the end of the first century of settlement, Bermuda's free and enslaved Blacks and Native Americans were still a small minority (which grew rapidly in the 18th century by combining with the Irish and Scots slaves, and a significant part of what might be termed the White Anglo population, dividing the populace into two demographic groupings, referred to as 'White' and 'Black' Bermudians).

The organization and efficiency of the militia progressed as the colony did, but, nonetheless, on arriving to begin his term as governor in 1687, Sir Robert Robinson, a naval officer, found his predecessor had failed to fulfill orders received in 1683, to ensure the proper maintenance of the fortifications and guns, and to keep them operations-ready day and night. In response to the parlous state of the colony's defences, Sir Robert shepherded through the Colonial Assembly the colony's first Militia Act.

Bibliography

"Defence, Not Defiance: A History Of The Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps", Jennifer M. Ingham (now Jennifer M. Hind), ISBN 978-0-9696517-1-0. Printed by The Island Press Ltd., Pembroke, Bermuda.

"Bermuda Forts 1612–1957", Dr. Edward C. Harris, The Bermuda Maritime Museum Press, The Bermuda Maritime Museum, P.O. Box MA 133, Mangrove Bay, Bermuda MA BX.

External links

- Bermuda Online: Bermuda's History from 1500 to 1701.

- Bermuda Online: Bermuda's British Army forts from 1609.

- Author's page on Bermuda Military History.

- American Journeys: Proceedings of the Virginia Assembly, 1619.

| Bermuda articles | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

|  | |||||||||

| Geography |

| ||||||||||

| Schools |

| ||||||||||

| Politics | |||||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||