| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Bialgebra" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In mathematics, a bialgebra over a field K is a vector space over K which is both a unital associative algebra and a counital coassociative coalgebra. The algebraic and coalgebraic structures are made compatible with a few more axioms. Specifically, the comultiplication and the counit are both unital algebra homomorphisms, or equivalently, the multiplication and the unit of the algebra both are coalgebra morphisms. (These statements are equivalent since they are expressed by the same commutative diagrams.)

Similar bialgebras are related by bialgebra homomorphisms. A bialgebra homomorphism is a linear map that is both an algebra and a coalgebra homomorphism.

As reflected in the symmetry of the commutative diagrams, the definition of bialgebra is self-dual, so if one can define a dual of B (which is always possible if B is finite-dimensional), then it is automatically a bialgebra.

| Algebraic structures |

|---|

| Group-like Group theory |

| Ring-like Ring theory |

| Lattice-like |

| Module-like |

| Algebra-like |

Formal definition

(B, ∇, η, Δ, ε) is a bialgebra over K if it has the following properties:

- B is a vector space over K;

- there are K-linear maps (multiplication) ∇: B ⊗ B → B (equivalent to K-multilinear map ∇: B × B → B) and (unit) η: K → B, such that (B, ∇, η) is a unital associative algebra;

- there are K-linear maps (comultiplication) Δ: B → B ⊗ B and (counit) ε: B → K, such that (B, Δ, ε) is a (counital coassociative) coalgebra;

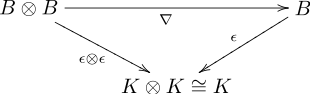

- compatibility conditions expressed by the following commutative diagrams:

- Multiplication ∇ and comultiplication Δ

- where τ: B ⊗ B → B ⊗ B is the linear map defined by τ(x ⊗ y) = y ⊗ x for all x and y in B,

- Multiplication ∇ and counit ε

- Comultiplication Δ and unit η

- Unit η and counit ε

Coassociativity and counit

The K-linear map Δ: B → B ⊗ B is coassociative if .

The K-linear map ε: B → K is a counit if .

Coassociativity and counit are expressed by the commutativity of the following two diagrams (they are the duals of the diagrams expressing associativity and unit of an algebra):

Compatibility conditions

The four commutative diagrams can be read either as "comultiplication and counit are homomorphisms of algebras" or, equivalently, "multiplication and unit are homomorphisms of coalgebras".

These statements are meaningful once we explain the natural structures of algebra and coalgebra in all the vector spaces involved besides B: (K, ∇0, η0) is a unital associative algebra in an obvious way and (B ⊗ B, ∇2, η2) is a unital associative algebra with unit and multiplication

- ,

so that or, omitting ∇ and writing multiplication as juxtaposition, ;

similarly, (K, Δ0, ε0) is a coalgebra in an obvious way and B ⊗ B is a coalgebra with counit and comultiplication

- .

Then, diagrams 1 and 3 say that Δ: B → B ⊗ B is a homomorphism of unital (associative) algebras (B, ∇, η) and (B ⊗ B, ∇2, η2)

- , or simply Δ(xy) = Δ(x) Δ(y),

- , or simply Δ(1B) = 1B ⊗ B;

diagrams 2 and 4 say that ε: B → K is a homomorphism of unital (associative) algebras (B, ∇, η) and (K, ∇0, η0):

- , or simply ε(xy) = ε(x) ε(y)

- , or simply ε(1B) = 1K.

Equivalently, diagrams 1 and 2 say that ∇: B ⊗ B → B is a homomorphism of (counital coassociative) coalgebras (B ⊗ B, Δ2, ε2) and (B, Δ, ε):

- ;

diagrams 3 and 4 say that η: K → B is a homomorphism of (counital coassociative) coalgebras (K, Δ0, ε0) and (B, Δ, ε):

- ,

where

- .

Examples

Group bialgebra

An example of a bialgebra is the set of functions from a finite group G (or more generally, any finite monoid) to , which we may represent as a vector space consisting of linear combinations of standard basis vectors eg for each g ∈ G, which may represent a probability distribution over G in the case of vectors whose coefficients are all non-negative and sum to 1. An example of suitable comultiplication operators and counits which yield a counital coalgebra are

which represents making a copy of a random variable (which we extend to all by linearity), and

(again extended linearly to all of ) which represents "tracing out" a random variable — i.e., forgetting the value of a random variable (represented by a single tensor factor) to obtain a marginal distribution on the remaining variables (the remaining tensor factors). Given the interpretation of (Δ,ε) in terms of probability distributions as above, the bialgebra consistency conditions amount to constraints on (∇,η) as follows:

- η is an operator preparing a normalized probability distribution which is independent of all other random variables;

- The product ∇ maps a probability distribution on two variables to a probability distribution on one variable;

- Copying a random variable in the distribution given by η is equivalent to having two independent random variables in the distribution η;

- Taking the product of two random variables, and preparing a copy of the resulting random variable, has the same distribution as preparing copies of each random variable independently of one another, and multiplying them together in pairs.

A pair (∇,η) which satisfy these constraints are the convolution operator

again extended to all by linearity; this produces a normalized probability distribution from a distribution on two random variables, and has as a unit the delta-distribution where i ∈ G denotes the identity element of the group G.

Other examples

Other examples of bialgebras include the tensor algebra, which can be made into a bialgebra by adding the appropriate comultiplication and counit; these are worked out in detail in that article.

Bialgebras can often be extended to Hopf algebras, if an appropriate antipode can be found; thus, all Hopf algebras are examples of bialgebras. Similar structures with different compatibility between the product and comultiplication, or different types of multiplication and comultiplication, include Lie bialgebras and Frobenius algebras. Additional examples are given in the article on coalgebras.

See also

Notes

- ^ Kassel 2012, p. 46.

- Kassel 2012, p. 45.

- Dăscălescu, Năstăsescu & Raianu 2001, p. 147.

- ^ Dăscălescu, Năstăsescu & Raianu 2001, p. 148.

- Dăscălescu, Năstăsescu & Raianu 2001, p. 151.

References

- Dăscălescu, Sorin; Năstăsescu, Constantin; Raianu, Șerban (2001), "4. Bialgebras and Hopf Algebras", Hopf Algebras: An introduction, Pure and Applied Mathematics, vol. 235, Marcel Dekker, ISBN 0-8247-0481-9.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel; Gubareni, Nadiya; Kirichenko, V. (2010). "Bialgebras and Hopf algebras. Motivation, definitions, and examples". Algebras, Rings and Modules Lie Algebras and Hopf Algebras. American Mathematical Society. pp. 131–173. ISBN 978-0-8218-5262-0.Download full-text PDF

- Kassel, Christian (2012). "The Language of Hopf Algebras". Quantum Groups. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-0783-2.

- Underwood, Robert G. (28 August 2011). An Introduction to Hopf Algebras. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-72766-0. Online Book

.

.

.

.

,

, or, omitting ∇ and writing

or, omitting ∇ and writing  ;

;

.

. , or simply Δ(xy) = Δ(x) Δ(y),

, or simply Δ(xy) = Δ(x) Δ(y), , or simply Δ(1B) = 1B ⊗ B;

, or simply Δ(1B) = 1B ⊗ B; , or simply ε(xy) = ε(x) ε(y)

, or simply ε(xy) = ε(x) ε(y) , or simply ε(1B) = 1K.

, or simply ε(1B) = 1K.

;

;

,

, .

. , which we may represent as a

, which we may represent as a  consisting of linear combinations of standard

consisting of linear combinations of standard

by linearity; this produces a normalized probability distribution from a distribution on two random variables, and has as a unit the delta-distribution

by linearity; this produces a normalized probability distribution from a distribution on two random variables, and has as a unit the delta-distribution  where i ∈ G denotes the identity element of the group G.

where i ∈ G denotes the identity element of the group G.