| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Chainsaw" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A chainsaw (or chain saw) is a portable handheld power saw that cuts with a set of teeth attached to a rotating chain driven along a guide bar.

Modern chainsaws are typically gasoline or electric and are used in activities such as tree felling, limbing, bucking, pruning, cutting firebreaks in wildland fire suppression, harvesting of firewood, for use in chainsaw art and chainsaw mills, for cutting concrete, and cutting ice. Precursors to modern chainsaws were first used in surgery, with patents for wood chainsaws beginning in the late 19th century.

A chainsaw comprises an engine, a drive mechanism, a guide bar, a cutting chain, a tensioning mechanism, and safety features. Various safety practices and working techniques are used with chainsaws.

History

In surgery

A "flexible saw", consisting of a fine serrated link chain held between two wooden handles, was pioneered in the late 18th century (c. 1783–1785) by two Scottish doctors, John Aitken and James Jeffray, for symphysiotomy and excision of diseased bone, respectively. It was illustrated in the second edition of Aitken's Principles of Midwifery, or Puerperal Medicine (1785) in the context of a pelviotomy. In 1806, Jeffray published Cases of the Excision of Carious Joints, which collected a paper previously published by H. Park in 1782 and a translation of an 1803 paper by French physician P. F. Moreau, with additional observations by Park and Jeffray. In it, Jeffray reported having conceived the idea of a saw "with joints like the chain of a watch" independently very soon after Park's original 1782 publication, but that he was not able to have it produced until 1790, after which it was used in the anatomy lab and occasionally lent out to surgeons. Park and Moreau described successful excision of diseased joints, particularly the knee and elbow, and Jeffray explained that the chainsaw would allow a smaller wound and protect the adjacent muscles, nerves, and veins. While symphysiotomy had too many complications for most obstetricians, Jeffray's ideas about the excision of the ends of bones became more accepted, especially after the widespread adoption of anaesthetics. For much of the 19th century the chainsaw was a useful surgical instrument, but it was superseded in 1894 by the Gigli twisted-wire saw, which was substantially cheaper to manufacture, and gave a quicker, narrower cut, without risk of breaking and being entrapped in the bone.

A precursor of the chainsaw familiar today in the timber industry was another medical instrument developed around 1830, by German precision mechanic and orthopaedist Bernhard Heine. This instrument, the osteotome, had links of a chain carrying small cutting teeth with the edges set at an angle; the chain was moved around a guiding blade by turning the handle of a sprocket wheel. As the name implies, this was used to cut bone.

For cutting wood

One of the earliest patents for an "endless chain saw" comprising a chain of links carrying saw teeth was granted to Frederick L. Magaw of Flatlands, New York in 1883, apparently for the purpose of producing boards by stretching the chain between grooved drums. A later patent incorporating a guide frame was granted to Samuel J. Bens of San Francisco on January 17, 1905, his intent being to fell giant redwoods. The first portable chainsaw was developed and patented in 1918 by Canadian millwright James Shand. After he allowed his rights to lapse in 1930, his invention was further developed by what became the German company Festo in 1933. The company, now operating as Festool, produces portable power tools. Other important contributors to the modern chainsaw are Joseph Buford Cox and Andreas Stihl; the latter patented and developed an electric chainsaw for use on bucking sites in 1926 and a gasoline-powered chainsaw in 1929, and founded a company to mass-produce them. In 1927, Emil Lerp, the founder of Dolmar, developed the world's first gasoline-powered chainsaw and mass-produced them.

World War II interrupted the supply of German chainsaws to North America, so new manufacturers sprang up, including Industrial Engineering Ltd (IEL) in 1939, the forerunner of Pioneer Saws Ltd and part of Outboard Marine Corporation, the oldest manufacturer of chainsaws in North America.

The first one-man chainsaw was introduced in 1950, though it was relatively heavy. By 1959, the average weight was around 12 kg (today, chainsaws typically weigh between 4 and 5 kg, with heavy-duty models ranging from 7 to 9 kg), and it quickly gained attention.

McCulloch in North America started to produce chainsaws in 1948. The early models were heavy, two-person devices with long bars. Often, chainsaws were so heavy that they had wheels like dragsaws. Other outfits used driven lines from a wheeled power unit to drive the cutting bar.

After World War II, improvements in aluminum and engine design lightened chainsaws to the point where one person could carry them. In some areas, the chainsaw and skidder crews have been replaced by the feller buncher and harvester.

Chainsaws have almost entirely replaced simple man-powered saws in forestry. They are made in many sizes, from small electric saws intended for home and garden use, to large "lumberjack" saws. Members of military engineer units are trained to use chainsaws, as are firefighters to fight forest fires and to ventilate structure fires.

Three main types of chainsaw sharpeners are used: handheld file, electric chainsaw, and bar-mounted.

The first electric chainsaw was invented by Stihl in 1926. Corded chainsaws became available for sale to the public from the 1960s onwards, but these were never as successful commercially as the older gas-powered type due to limited range, dependency upon the presence of an electrical socket, plus the health and safety risk of the blade's proximity to the cable.

For most of the early 21st century petrol driven chainsaws remained the most common type, but they faced competition from cordless lithium battery powered chainsaws from the late 2010s onwards. Although most cordless chainsaws are small and suitable only for hedge trimming and tree surgery, Husqvarna and Stihl began manufacturing full size chainsaws for cutting logs during the early 2020s. Battery powered chainsaws should eventually see increased market share in California due to state restrictions planned to take effect in 2024 on gas powered gardening equipment.

Construction

A chainsaw consists of several parts:

Engine

Chainsaw engines are traditionally either a two-stroke single-cylinder gasoline (petrol) internal combustion engine (usually with a cylinder volume of 30 to 120 cm) or an electric motor driven by a battery or electric power cord. In a petrol chainsaw, fuel is generally supplied to the engine by a carburetor at the intake. Two-stroke engines have been preferred for chainsaws due to their higher power-to-weight ratio and simplicity.

Hydraulic power may be used for chainsaws for underwater use.

To allow use in any orientation, modern gas chainsaws use a diaphragm carburetor, which draws fuel from the tank using the alternating pressure differential within the crankcase. Early engines used carburetors with gravity fed float chambers, which caused the engine to stall when tilted. The carburetor may need to be adjusted to maintain an appropriate idle speed and air-fuel ratio, such as when moving to a higher/lower altitude or as the air filter clogs. Carburetors are adjusted either by the operator or, in some saws, automatically by an electronic control unit.

To prevent vibration induced injury and reduce user fatigue, saws generally have an anti-vibration system to physically decouple the handles from the engine and bar. This is achieved by constructing the saw in two pieces, connected by springs or rubber in the same way an automobile suspension isolates the chassis from the wheels and road. In cold weather, carburetor icing can occur, so many saws have a vent between the cylinders and carburetor which may be opened to allow hot air to pass. Cold temperature can also contribute to vibration-induced injury, and some saws have a small alternator connected to resistive heating elements in the handles and/or carburetor.

Drive mechanism

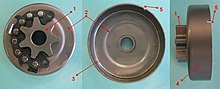

Typically, a centrifugal clutch and sprocket are used. The centrifugal clutch expands with increasing speed, engaging a drum. On this drum sits either a fixed sprocket or an exchangeable one. The clutch has three jobs: When the engine runs idle (typically 2500–2700 rpm) the chain does not move. When the clutch is engaged and the chain stops in the wood for another reason, it protects the engine. Most importantly, it protects the operator in case of a kickback. Here, the chain brake stops the drum, and the clutch releases immediately.

Guide bar

A guide bar, typically an elongated bar with a round end of wear-resistant alloy steel typically 40 to 90 cm (16 to 36 in) in length, is used. An edge slot guides the cutting chain. Specialized, loop-style bars, called bow bars, were also used at one time for bucking logs and clearing brush, although they are now rarely encountered due to increased hazards of operation.

All guide bars have some elements for operation:

Gauge

The lower part of the chain runs in the gauge. Here, the lubrication oil is pulled by the chain to the nose. This is basically the thickness of the drive links.

- 0.063 in or 1.6 mm

- 0.058 in or 1.5 mm

- 0.050 in or 1.3 mm

- 0.043 in or 1.1 mm

Oil holes

The end of the saw power head has two oil holes, one on each side. These holes must match with the outlet of the oil pump. The pump sends the oil through the hole in the lower part of the gauge.

Saw bar producers provide a large variety of bars matching different saws.

Grease holes at bar nose

Through this hole, grease is pumped, typically each tank filling to keep the nose sprocket well lubricated.

Guide slot

Here, one or two bolts from the saw run through. The clutch cover is put on top of the bar and it is secured through these bolts. The number of bolts is determined by the size of the saw.

Bar types

Different bar types are available:

- Laminated bars consist of different layers to reduce the weight of the bar.

- Solid bars are solid steel, intended for professional use. They commonly have an exchangeable nose, since the sprocket at the bar nose wears out faster than the bar.

- Safety bars are laminated bars with a small sprocket at the nose. The small nose reduces the kickback effect. Such bars are used on consumer saws.

Cutting chain

Main article: Saw chainUsually, each segment in a chain (which is constructed from riveted metal sections similar to a bicycle chain, but without rollers) features small, sharp, cutting teeth. Each tooth takes the form of a folded tab of chromium-plated steel with a sharp angular or curved corner and two beveled cutting edges, one on the top plate and one on the side plate. Left-handed and right-handed teeth are alternated in the chain. Chains are made in varying pitch and gauge; the pitch of a chain is defined as half of the length spanned by any three consecutive rivets (e.g., 8 mm, 0.325 inch), while the gauge is the thickness of the drive link where it fits into the guide bar (e.g., 1.5 mm, 0.05 inch). The conventional "full complement" chain has one tooth for every two drive links. "Full skip" chain has one tooth for every three drive links. Built into each tooth is a depth gauge or "raker", which rides ahead of the tooth and limits the depth of cut, typically to around 0.5 mm (0.025"). Depth gauges are critical to safe chain operation. If left too high, they cause very slow cutting; if filed too low, the chain becomes more prone to kick back. Low depth gauges also cause the saw to vibrate excessively. Vibration is uncomfortable for the operator and is detrimental to the saw.

Tensioning mechanism

Main article: TensionerThe tension of the cutting chain is adjusted so that it neither binds on nor comes loose from the guide bar. The tensioner for doing so is either operated by turning a screw or a manual wheel. The tensioner is either in a lateral position underneath the exhaust or integrated into the clutch cover.

Lateral tensioners have the advantage that the clutch cover is easier to mount, but the disadvantage that it is more difficult to reach nearby the bar. Tensioners through the clutch cover are easier to operate, but the clutch cover is more difficult to attach.

When turning the screw, a hook in a bar hole moves the bar either out (tensioning) or in, making the chain loose. Tension is right when it can be moved easily by hand and not hanging loose from the bar. When tensioning, hold the bar nose up and pull the bar nuts tight. Otherwise, the chain might derail.

The underside of each link features a small, metal finger called a "drive link", which locates the chain on the bar, helps to carry lubricating oil around the bar, and engages with the engine's drive sprocket inside the body of the saw. The engine drives the chain around the track by a centrifugal clutch, engaging the chain as engine speed increases under power, but allowing it to stop as the engine speed slows to idle speed.

Consistent improvement to overall chainsaw design, including adding safety features, has taken place over the years. These include chain-brake systems, better chain design, and lighter, more ergonomic saws, including fatigue-reducing antivibration systems.

As chainsaw carving has become more popular, manufacturers are making special short, narrow-tipped bars (called "quarter-tipped" "nickel-tipped", or "dime-tipped" bars, based on the size of their tips). Some chainsaws are built specifically for carving applications. Echo sponsors a carving series.

Safety features

Today's chainsaws have multiple safety features to protect the operator. These include:

- Chain brake

- A chain brake activator is located forward of the upper handle and is activated by a kickback event. When triggered, it tensions a band around the clutch drum, stopping the chain within milliseconds.

- A chain catcher is located between the saw body and the clutch cover. In most cases, it resembles a hook made of aluminum. It is used to stop the chain when it derails from the bar and shortens the length of the chain. When derailing, the chain swings from underneath the saw towards the operator. This prevents the chain from hitting the operator, which hits the rear handle guard instead.

- A rear handle guard protects the hand of the operator when the chain derails.

- Some chains have safety features as safety links as on micro chisel saws. These links keep the saw close to the gap between two cutting links and lift the chain when the space at the safety link is full with saw chips, which lifts the chain and lets it cut slower. Nonprofessional chains have less aggressive teeth, by having shallower depth gauges.

Maintenance

| This section contains instructions, advice, or how-to content. Please help rewrite the content so that it is more encyclopedic or move it to Wikiversity, Wikibooks, or Wikivoyage. (October 2023) |

Two-stroke chainsaws require about 2–5% of oil in the fuel to lubricate the engine, while the motor in electrical chain-saws is normally lubricated for life. Most modern gasoline-operated saws today require a fuel mix of 2% (1:50). Gasoline that contains ethanol can result in problems for the equipment because ethanol dissolves plastic, rubber, and other material. This leads to problems, especially on older equipment. A workaround for this problem is to run fresh fuel only and run the saw dry at the end of the work.

Separate chain oil or bar oil is used for the lubrication of the bar and chain on all types of chainsaws. The chain oil is depleted quickly because it tends to be thrown off by chain centrifugal force, and it is soaked up by sawdust. On two-stroke chainsaws, the chain oil reservoir is usually filled up at the same time as refueling. The reservoir is normally large enough to provide sufficient chain oil between refueling. Lack of chain oil, or using an oil of incorrect viscosity, is a common source of damage to chainsaws, and tends to lead to rapid wear of the bar, or the chain seizing or coming off the bar. In addition to being quite thick, chain oil is particularly sticky (due to "tackifier" additives) to reduce the amount thrown off the chain. Although motor oil is a common emergency substitute, it is lost even faster, so leaves the chain under-lubricated.

The oil is pumped from a small pump to a hole in the bar. From there, the lower ends of each chain drive link take a portion of the oil into the gauge towards the bar nose. The pump outlet and bar hole must be aligned. Since the bar is moving out and inwards depending on the chain length, the oil outlet on the saw side has a banana-style long shape.

Chains must be kept sharp to perform well. They become blunt rapidly if they touch soil, metal, or stones. When blunt, they tend to produce powdery sawdust, rather than the longer, clean shavings characteristic of a sharp chain; a sharp saw also needs very little force from the operator to push it into the cut. Specially-hardened chains (made with tungsten carbide) are used for applications where the soil is likely to contaminate the cut, such as for cutting through roots.

A clear sign of a blunt chain is the vibrations of the saw. A sharp chain pulls itself into the wood without pressing on the saw.

Since the air intake filter tends to clog up with sawdust, it must be cleaned from time to time but is not a problem during normal operation.

Safety

Protective clothing is designed to protect operators in the event of a moving chain touching their clothing by snarling the chain and sprocket, by using special synthetic fibers woven into the garment. Despite safety features and protective clothing, injuries can still arise from chainsaw use, from the large forces involved in the work, from the fast-moving, sharp chain, or the vibration and noise of the machinery.

A common accident arises from "kickback" when a chain tooth at the tip of the guide bar catches on wood without cutting through it. This throws the bar (with its moving chain) in an upward arc toward the operator, which can cause serious injury or even death.

Another dangerous situation occurs when heavy timber begins to fall or shift before a cut is complete. The chainsaw operator may be trapped or crushed. Similarly, timber falling in an unplanned direction may harm the operator or other workers, or an operator working at a height may fall or be injured by falling timber.

Like other hand-held machinery, the operation of chainsaws can cause vibration white finger, tinnitus, or industrial deafness. These symptoms were very common before vibration dampening using rubber or steel spring was introduced. Heated handles are additional help. Newer, lighter, and easier to wield cordless electric chainsaws use brushless motors, which further decrease noise and vibration compared to traditional petroleum-powered models.

The risks associated with chainsaw use mean that protective clothing such as chainsaw boots, chaps, and hearing protectors are normally worn while operating them, and many jurisdictions require that operators be certified or licensed to work with chainsaws. Injury can also result if the chain breaks during operation due to poor maintenance or attempting to cut inappropriate materials.

Gasoline-powered chainsaws expose operators to harmful carbon monoxide gas, especially indoors or in partially enclosed outdoor areas.

Drop starting, or turning on a chainsaw by dropping it with one hand while pulling the starting cord with the other, is a safety violation in most states in the U.S. Keeping both hands on the saw for stability is essential for safe chainsaw use.

Safe and effective chainsaw and crosscut use on federally administered public lands within the United States has been codified since 2016 in the Final Directive for National Saw Program issued by the United States Forest Service, which specifies the training, testing, and certification process for employees and unpaid volunteers who operate chainsaws within public lands.

Working techniques

Chainsaw training is designed to provide working technical knowledge and skills to safely operate the equipment.

- Sizeup – This is scouting and planning safe cuts for the felling direction, danger zones, and retreat paths, before starting the saw. The tree's location relative to other objects, support, and tension determines a safe fall, splits off, or if the saw will jam. Several factors to consider are tree lean and bend, wind direction, branch arrangement, snow load, obstacles and damaged, rotting tree parts, which might behave unexpectedly when cut. A tree may have to fall in its natural direction if it is too dangerous or impossible to fell in a desired direction. The aim is for the tree to fall safely for limbing and cross-cutting the log. The goal is to avoid having the tree fall on another tree or obstacle.

- Felling – After clearing the tree's base undergrowth for the retreat path and the felling direction; felling is properly done with three main cuts. To control the fall, the directional cut line should run 1/4 of the tree diameter to make a 45-degree wedge, which should be 90 degrees to the felling direction and perfectly horizontal. The top cut should be made first and then the bottom cut is made to form the directional cut line at the wedge point. A narrow or nonexistent hinge lessens felling direction control. From the opposite side of the wedge, the final felling cut is finished one-tenth of the tree diameter from the direction cut line. The felling cut is made horizontally and slightly (1.5–2 inches; 5.1 cm) above the bottom cut. When the hinge is properly set, the felling cut will begin the fall in the desired direction. A sitback is when a tree moves back opposite the intended direction. Placing a wedge in the felling cut can prevent a sitback from pinching the saw.

- Freeing – Working a badly fallen tree that may have become trapped in other trees. Working out maximum tension locations to decide the safest way to release tension, and a winch may be needed in complicated situations. To avoid cutting straight through a tree in tension, one or two cuts at the tension point of sufficient depth to reduce tension may be necessary. After tension releases, cuts are made outside the bend.

- Limbing – Cutting the branches off the log. The operator must be able to properly reach the cut to avoid kickback.

- Bucking – Cross-cutting the felled log into sections. Setup is made to avoid binding the chainsaw within the changing log tensions and compressions. Safe bucking is started at the log high-side and then sections worked offside, toward the butt end. The offside log falls and allows for gravity to help prevent binds. The log's kerf movement while cutting can help to indicate binds. Additional equipment (lifts, bars, wedges, and winches) and special cutting techniques can help prevent binds.

- Binds – This is when the chainsaw is at risk or is stuck in the log compression. A log bound chainsaw is unsafe and must be carefully removed to prevent equipment damage.

- Top bind – The tension area on log bottom, compression on top.

- Bottom bind – The tension area on log top, compression on bottom.

- Side bind – Sideways pressure exerted on the log.

- End bind – Weight compresses the log's entire cross-section.

- Brushing and slashing – This is quickly clearing small trees and branches under five inches (13 cm) in diameter. Hand piler may follow along to move out debris.

Cutting

Chainsaws with specially designed bar-and-chain combinations have been developed as tools for use in chainsaw art and chainsaw mills. Specialized chainsaws are used for cutting concrete during construction developments. Chainsaws are sometimes used for cutting ice; for example, ice sculpture and winter swimming in Finland.

As a sawmill

When fastened into a special guide frame, a chainsaw can be used as a portable sawmill to cut bulk wood into planks or boards. Such usage is called a chainsaw mill or Alaskan sawmill.

Cutting stone, concrete, and brick

Special chainsaws can cut concrete, brick, and natural stone. These use similar chains to ordinary chainsaws, but with cutting edges embedded with diamond grit. They may use gasoline or hydraulic power, and the chain is lubricated with water, because of high friction and to remove stone dust. The machine is used in construction, for example, in cutting deep, square holes in walls or floors, in stone sculpture for removing large chunks of stone during pre-carving, by fire departments for gaining access to buildings, and in restoration of buildings and monuments for removing parts with minimal damage to the surrounding structure. More recently, concrete chainsaws with electric motors of 230 volts have also been developed.

Because the material to be cut is not fibrous, much less kickback occurs. So, the most-used method of cutting is plunge-cutting, by pushing the tip of the blade into the material. With this method, square cuts as small as the blade width can be achieved. Pushback can occur if a block shifts when nearly cut through and pinches the blade, but overall, the machine is less dangerous than a wood-cutting chainsaw.

Underwater work

Chainsaws are used for underwater cutting by professional divers. They are usually driven by hydraulic power supplied from the surface and operated by commercial divers using surface-supplied diving equipment. Underwater chainsaw cutting may also be used by public safety divers.

Hydraulic chainsaws can be used to cut wood, concrete, brick and steel if the appropriate chain is used. Underwater cutting may be done in conditions of moving water and low visibility, which can increase risk, and appropriate safety precautions and suitable procedures are required for safety.

Underwater wood structures may include bridge pilings, pier, and dock timbers. Chain saws generally include an interlocking safety trigger with hand guard.

See also

References

- "Definition of chain saw". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- Skippen, M; Kirkup, J; Maxton, R M; McDonald, S W (2004). "The Chain Saw – A Scottish Invention". Scottish Medical Journal. 49 (2): 72–75. doi:10.1177/003693300404900218. ISSN 0036-9330. PMID 15209147. S2CID 19878683.

- Aitken, John (1785). Principles of Midwifery, or Puerperal Medicine (2nd ed.). Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh Lying-In Hospital. pp. 76–84, Plate XII Fig. 2.

- Park, H.; Moreau, P. F.; Jeffray, James (1806). Jeffray, James (ed.). Cases of the Excision of Carious Joints by H. Park and P. F. Moreau, with Observations by James Jeffray, M.D. Translated by Jeffray, James. Glasgow, Scotland: John Scrymgeour.

- "Cases of the Excision of Carious Joints". Critical Analysis. Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal (Review). 3 (9). Edinburgh, Scotland: Archibald Constable & Company: 90–96. January 1807. PMC 5711164.

- Johnson, Robert Scott; Sippo, Dorothy A.; Swan, Kenneth G. (August 2010). "The Flexible Chain Saw During the American Civil War". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 69 (2): 455–458. doi:10.1097/ta.0b013e3181e4f297. PMID 20699757.

- Lennox, Doug. Now You Know: The Book of Answers, Volume 4. Toronto: Dundurn Press. 175. Print.

- Seufert, Wolf D. Seufert; Rogers, Fred B.; Risse, Guenter B. (October 1980). Schullian, Dorothy M. (ed.). "The Chain Osteom by Heine". Notes and Events. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 35 (4). Oxford University Press: 454–465. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXXV.4.454. JSTOR 24625567. PMID 7005321.

- US patent 279780, Frederick L. Magaw, "CHAIN SAWING-MACHINE", published 1883-04-17, issued 1883-04-17

- "Endless chain saw". Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Wardrop, Jim (June 1976). "British Columbia's experience with early chain saws". Material Culture Review. 2. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- CA patent 186260A, James Shand, "SAW", published 1918-08-27, issued 1918-08-27

- Reid, Mark Collin (2017). "Timber!". Canada's History. 97 (5): 20–23. ISSN 1920-9894.

- bravodeluxe (2013-02-05). "The History of the Chainsaw (Guest Post)". Hankering for History. Retrieved 2024-11-28.

- ""Steady Growth, Industry Firsts Noted in Long Pioneer History", Chain Saw Age August 1972". Archived from the original on 2014-04-27. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- WSL (EN), Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL-. "The History of the Chainsaw". www.waldwissen.net. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- "Everything You Need to Know About Poulan Chainsaws". Chainsaw Selector. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- Lennox, Doug (September 16, 2006). Now You Know, Volume 4: The Book of Answers. Dundurn. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4597-1817-3 – via Google Books.

- McClain, Troy (May 22, 2013). Firewood: An Expert Introduction to Equipment, Trees, Harvesting and Understanding This Valuable Resource. eBookIt.com. ISBN 978-1-4566-1229-0 – via Google Books.

- "Popular Science". Bonnier Corporation. May 9, 1977. p. 186 – via Google Books.

- Hinson, Tamara (October 7, 2021). "Best chainsaws to trim trees, slice logs and prune triffid-like bushes into shape". Evening Standard.

- "Become a Landscaping and Lawn Care Pro With These Mini Chainsaws". Popular Mechanics. March 28, 2023.

- "The 14 Best Electric Chainsaws in 2023". Popular Mechanics. October 2, 2023.

- "California's Ban on Gas-Powered Lawn and Garden Equipment Will Impact Homeowners". Popular Mechanics. October 14, 2021.

- "California regulators sign off on phaseout of new gas-powered lawn mowers, leaf blowers". Los Angeles Times. 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2022-03-04.

- "How to mix 2 stroke fuel". www.husqvarna.com. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ "Commercial Diving Tools: Part One". prodivertc.com. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- Krajnak, Kristine (2018). "Health effects associated with occupational exposure to hand-arm or whole body vibration". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 21 (5): 320–334. Bibcode:2018JTEHB..21..320K. doi:10.1080/10937404.2018.1557576. ISSN 1521-6950. PMC 6415671. PMID 30583715.

- Bovenzi, M.; Franzinelli, A.; Mancini, R.; Cannavà, M. G.; Maiorano, M.; Ceccarelli, F. (Nov 1995). "Dose-response relation for vascular disorders induced by vibration in the fingers of forestry workers". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 52 (11): 722–730. doi:10.1136/oem.52.11.722. ISSN 1351-0711. PMC 1128352. PMID 8535491.

- Gemne, G. (May 1994). "Pathophysiology of white fingers in workers using hand-held vibrating tools". Nagoya Journal of Medical Science. 57 Suppl: 87–97. ISSN 0027-7622. PMID 7708114.

- "Masters of the Chainsaw – Chainsaw Competitions". www.mastersofthechainsaw.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "ECHO Carving Series". ECHO Incorporated. 2022 .

- "Ethanol free fuel". hsqGlobal. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Chain Saw Safety Manual" (PDF). Stihl. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31.

- Stihl, Chain Saw Safety Manual, pp. 12–16

- "Preventing Chain Saw Injuries During Tree Removal After a Disaster". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- Vibration Syndrome. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Current Intelligence Bulletin 38: March 29, 2983. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- Carbon Monoxide Hazards from Small Gasoline Powered Engines. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- Saw, Dan | Fire and (2023-04-06). "The Dangers Of Drop Starting A Chainsaw & Approved Techniques". Fire And Saw. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- Final Directive for National Saw Program Federal Register. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- Chain Saw and Crosscut Saw Training Course Student's Guidebook 2006 Edition. USDA, US Forest Service. 29 December 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Jonsered Operator's Manual (1153137-95Rev.2). 2012-03-04. pp. 16–18.

- Husqvarna Operator's Manual (115 42 1549 Rev. 6). 2009-12-29. pp. 27–28, 43.

- "Electric concrete chainsaw 230V". Archived from the original on 2014-01-07. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

External links

- "How a Chainsaw Works". Popular Science. August 1951.

| Forestry tools and equipment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tree planting, afforestation |

|  |

| Mensuration | ||

| Fire suppression | ||

| Axes |

| |

| Saws | ||

| Logging | ||

| Other | ||

| ||

| Lumberjack sports | ||

|---|---|---|

| Events |

|  |

| Competitions | ||