A cuckoo clock is a type of clock, typically pendulum driven, that strikes the hours with a sound like a common cuckoo call and has an automated cuckoo bird that moves with each note. Some move their wings and open and close their beaks while leaning forwards, whereas others have only the bird's body leaning forward. The mechanism to produce the cuckoo call has been in use since the middle of the 18th century and has remained almost without variation.

It is unknown who invented the cuckoo clock and where the first one was made. It is thought that much of its development and evolution was made in the Black Forest area in southwestern Germany (in the modern state of Baden-Württemberg), the region where the cuckoo clock was popularized and from where it was exported to the rest of the world, becoming world-famous from the mid-1850s on. Today, the cuckoo clock is one of the favourite souvenirs of travellers in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Eastern France. It has become a cultural icon of Germany.

Characteristics

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

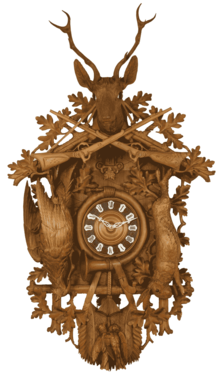

The design of a cuckoo clock is now conventional. Many are made in the "traditional style", which are made to hang on a wall. The classical or traditional type includes two subgroups; the carved ones, whose wooden cases are decorated with leaves, animals, etc., and a second one with cases in the shape of a chalet. They have an automaton of a bird that appears through a small trap door when the clock strikes. The cuckoo bird is activated by the clock movement as the clock strikes by means of an arm that is triggered on the hour and half hour.

There are two kinds of movements: one-day (30-hour) and eight-day clockworks. Some have musical devices, and play a tune on a Swiss music box after striking the hours and half-hours. Usually the melody sounds only at full hours in eight-day clocks and both at full and half hours in the one-day timepieces. Musical cuckoo clocks frequently have other automata which move when the music box plays. Today's cuckoo clocks are almost always weight driven. The weights are made of cast iron usually in a pine cone shape and the "cuckoo" sound is created by two tiny gedackt pipes in the clock, with bellows attached to their tops. The clock's movement activates the bellows to send a puff of air into each pipe alternately when the timekeeper strikes.

Since the 1970s, quartz battery-powered cuckoo clocks have become available. As with their mechanical counterparts, the cuckoo bird emerges from its enclosure and moves up and down, but often on the quartz timepieces it also flaps its wings and open its beak while it sings. Just before the call, and in case it has a door, the single or double door opens and the bird emerges as usual, but only on the full hour, and they do not have a gong wire chime. The movement of the cuckoo in such clocks is regulated by an electromagnet that pulses on and off, attracting a weight, that acts as a fulcrum, connected to the tail of the plastic cuckoo, thus moving the bird up and down in its enclosure.

In quartz cuckoos, different systems have been used to produce the bird's call; the usual bellows, a digital recording of a real cuckoo in the wild (with a corresponding echo accompanied by the sound of a waterfall and other birds in the background) or a recording of the bird's call only. In musical versions, the hourly chime is followed by the replay of one of twelve popular melodies (one for each hour). Some musical quartz clocks in the chalet style also reproduce many of the popular automata found on mechanical musical clocks, such as beer drinkers, wood-choppers, and jumping deer.

Uniquely, quartz cuckoo clocks often include a sensor, so that when the lights are turned off at night they automatically silence the hourly chime. Others are pre-programmed not to strike between a set of pre-determined hours. Whether this is controlled by a light sensor or pre-programmed, the function is referred to as a "night silence" feature. On quartz wall clocks in the traditional style, the weights are conventionally cast in the shape of pine cones made of plastic rather than iron. The pendulum bob is often another carved leaf. Here, the weights and pendulum are purely ornamental as the clock is driven by battery power.

History

First modern cuckoo clocks

In 1629, many decades before clockmaking was established in the Black Forest, an Augsburg merchant by the name of Philipp Hainhofer (1578–1647) penned one of the first known descriptions of a modern cuckoo clock. In Dresden, he visited the Kunstkammer (Cabinet of curiosities) of Prince Elector August von Sachsen. One of the rooms contained a chiming clock with a moving bird, a cuckoo announcing every quarter of an hour, which he briefly described as: "A beautiful chiming clock, inside a cuckoo, indicating the quarter hours with its beak and call, the hours with its flapping wings and pour sugar from its tail" (translated from the German). Hainhofer does not describe what this clock may have looked like and who built it. This piece is no longer part of the Dresden Green Vault collection, but appears in a 1619 inventory book as: "In addition, there is also a new entry. 1 Clock with a cuckoo that yells. It stands on a black pedestal made of ebony on the barber's chest" (translated from the German).

The Dresden timepiece should not have been unique, because the mechanical cuckoo was considered part of the known mechanical arts in the 17th century. In a widely known handbook on music, Musurgia Universalis (1650), the scholar Athanasius Kircher describes a mechanical organ with several automated figures, including a mechanical cuckoo. This book contains the first documented description—in words and pictures—of how a mechanical cuckoo works. Kircher did not invent the cuckoo mechanism, because this book, like his other works, is a compilation of known facts into a handbook for reference purposes. The engraving clearly shows all the elements of a mechanical cuckoo. The bird automatically opens its beak and moves both its wings and tail. Simultaneously, there is heard the whistle—call of the cuckoo, created by two organ pipes, tuned to a minor or major third. There is only one fundamental difference from the Black Forest-type cuckoo mechanism: The functions of Kircher's bird are not governed by a count wheel in a strike train, but a pinned program barrel synchronizes the movements and sounds of the bird.

On the other hand, in 1669 Domenico Martinelli, in his handbook on elementary clocks Horologi Elementari, suggests using the call of the cuckoo to indicate the hours. Starting at that time the mechanism of the cuckoo clock was known. Any mechanic or clockmaker, who could read Latin or Italian, knew after reading the books that it was feasible to have the cuckoo announce the hours.

Subsequently, cuckoo clocks appeared in regions that had not been known for their clockmaking. For instance, the Historische Nachrichten (1713), an anonymous publication generally attributed to Court Preacher Bartholomäus Holzfuss, mentions a musical clock in the Oranienburg palace in Berlin. This clock, originating in West Prussia, played eight church hymns and had a cuckoo that announced the quarter hours. Unfortunately this clock, like the one mentioned by Hainhofer in 1629, can no longer be traced today.

In the 18th century, people in the Black Forest started to build cuckoo clocks.

First cuckoo clocks made in the Black Forest

It is not clear who built the first cuckoo clocks in the Black Forest, but there is unanimity that the unusual clock with the bird call very quickly conquered the region. By the middle of the 18th century, several small clockmaking shops between Neustadt and Sankt Georgen were making cuckoo clocks out of wood and shields decorated with paper. After a journey through south-west Germany in 1762, Count Giuseppe Garampi, Prefect of the Vatican Archives, remarked: "In this region large quantities of wooden movement clocks are made, and even if they were not completely unknown earlier, they have now been perfected, and one has started to equip them with the cuckoo's call."

It is hard to judge how large the proportion of cuckoo clocks was among the total production of early days Black Forest clocks. Based on the proportion of pieces surviving to the present, it must have been a small fraction of the total production. Especially 18th century cuckoo clocks, in which all the parts of the movement, including gears, were made of wood. They are extremely rare, Wilhelm Schneider was only able to list a dozen of pieces with wooden movements in his book Frühe Kuckucksuhren (Early Cuckoo Clocks) (2008). The cuckoo clock remained a niche product until the middle of the 19th century, made by a few specialized workshops.

Regarding its murky origins, there are two main fables from the first two chroniclers of Black Forest horology which tell contradicting stories about it: The first is from Father Franz Steyrer, written in his Geschichte der Schwarzwälder Uhrmacherkunst (History of the Art of Clockmaking in the Black Forest) in 1796. He describes a meeting, happened around 1742, between two clock peddlers (Uhrenträger, literally "clock carriers", who carried the dials and movements on their backs displayed on huge backpacks), Joseph Ganther from Neukirch (Furtwangen) and Joseph Kammerer from Furtwangen, who met a travelling Bohemian merchant who sold wooden cuckoo clocks. When they returned home, they brought with them this novelty, since it had caught their eyes, and show it to Michael Dilger from Neukirch and Matthäus Hummel from Glashütte, who were very pleased with it and began to copy it. Its popularity grew in the region and more and more clockmakers started making them. With regard to this chronicle, the historian Adolf Kistner claimed in his book Die Schwarzwälder Uhr (The Black Forest Clock), published in 1927, that there is not any Bohemian cuckoo clock in existence to verify the thesis that such a clock was used as a sample to copy and produce Black Forest cuckoo clocks. Bohemia had no fundamental clockmaking industry during that period.

The second story is related by another priest, Markus Fidelis Jäck, in a passage extracted from his report Darstellungen aus der Industrie und des Verkehrs aus dem Schwarzwald (Descriptions of the Industry and Transport of the Black Forest), (1810) said as follows: "The cuckoo clock was invented (in the early 1730s) by a clock-master from Schönwald. This craftsman adorned a clock with a moving bird that announced the hour with the cuckoo-call. The clock-master got the idea of how to make the cuckoo-call from the bellows of a church organ". Unfortunately, neither Steyrer nor Jäck quote any sources for their claims, making them unverifiable.

As time went on, the second version became the more popular, and is the one generally related today, though evidence suggests its inaccuracy. This type of clock is much older than clockmaking in the Black Forest. As early as 1650, the mechanical cuckoo was part of the reference book knowledge recorded in handbooks. It took nearly a century for the cuckoo clock to find its way to the Black Forest, where for many decades it remained a tiny niche product.

In addition, R. Dorer pointed out in 1948 that Franz Anton Ketterer (1734–1806) could not have been the inventor of the cuckoo clock in 1730, because he had not yet been born. This statement was corroborated by Gerd Bender in the most recent edition of the first volume of his work Die Uhrenmacher des hohen Schwarzwaldes und ihre Werke (The Clockmakers of the High Black Forest and their Works) (1998) in which he wrote that the cuckoo clock was not native to the Black Forest and also stated that: "There are no traces of the first production line of cuckoo clocks made by Ketterer". Schaaf, in Schwarzwalduhren (Black Forest Clocks) (1995), provides his own research which leads to the earliest cuckoos having been built in the Franconia and Lower Bavaria area, in the southeast of Germany, (forming nowadays the northern two-thirds of the Free State of Bavaria), in the direction of Bohemia (nowadays the main region of the Czech Republic), which he notes, lends credence to the Steyrer version.

Although the idea of placing an automaton cuckoo bird in a clock to announce the passing of time did not originate in the Black Forest, the cuckoo clock as it is known today (in its traditional form decorated with wood carvings) comes from this region located in southwest Germany. The Black Forest people who created the cuckoo clock industry developed it, and still come up with new designs and technical improvements.

Even though the functionality of the cuckoo mechanism has remained basically unchanged, the appearance has changed as case designs and clock movements evolved in the region. Around 1800, the first lacquered shield clocks appeared, the so-called Lackschilduhr ("lacquered shield clock"), characterized by having a painted flat square wooden face behind which all the clockwork was attached. On top of the square was usually a semicircle of highly decorated painted wood which contained the door for the cuckoo. These usually depicted floral motifs, like roses, and often had a painted column, on either side of the chapter ring, others were decorated with fruits as well. Some pieces also bore the names of the bride and bridegroom on the dial, which were normally painted by women. There was no cabinet surrounding the clockwork in this model. This design was the most prevalent during the first half of the 19th century.

By the middle of the 19th century, Black Foresters began to experiment with a variety of forms. In the 1840s, the Beha company had already been selling Biedermeier style table cuckoo clocks. Up until now, clocks had mainly been manufactured with a large shield hiding the movement behind, without a case surrounding it. Now, for the first time, timepieces with a real case were produced in large numbers. These clocks with their simple geometric shapes, some with small columns on both sides of the dial for decoration, are reminiscent of the art of the Biedermeier period. Such pieces were built between 1840 and the 1890s - and sometimes a cuckoo was included in these simple "Biedermeier clocks". Some models had also a painting of a person or animal with moving eyes.

Towards the middle of the 19th century until the 1880s, picture frame cuckoo clocks also became available. As the name suggests, these wall timepieces consisted of a picture frame, usually with a typical Black Forest scene painted on a wooden background or a sheet metal, lithography and screen-printing were other techniques used. Other common themes depicted were; hunting, love, family, death, birth, mythology, military and Christian religious scenes. Works by painters such as Johann Baptist Laule (1817–1895) and Carl Heine (1842–1882) were used to decorate the fronts of this and other types of clocks. The painting was almost always protected by a glass and some models displayed a person or an animal with blinking or flirty eyes as well, being operated by a simple mechanism worked by means of the pendulum swinging. The cuckoo normally took part in the scene painted, and would pop out in 3D, as usual, to announce the hour.

Another type of picture frame clock (Rahmenuhr) produced in the region from the middle of the 19th century, was based on a Viennese model from around 1830. The front of these timepieces was decorated with a serially stamped brass plate. The brass was given a gold-coloured surface by polishing it or treating it with nitric acid. Some of these pieces, which were produced in large numbers up until the 1880s, were also available with a cuckoo mechanism.

As for house-shaped cases, in the 1870s the Beha company marketed table and wall models of considerable size, so-called Herrenhäusle ("House of Lords", a manor house or mansion), whose detailed wooden cases replicated attic windows from where the cuckoo pop out, a shingle roof with chimney, rain gutters and downpipes, etc.

On the other hand, from the 1860s until the early 20th century, cases were manufactured in a wide variety of styles such as; Neoclassical or Georgian (certain pieces also displayed a painting), neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, neo-Baroque, Art Nouveau, etc., becoming a suitable decorative object for the bourgeois home. These timepieces are less common than the popular ones looking like gatekeeper-houses (Bahnhäusle style clocks) and they could be mantel, wall or bracket clocks.

However, the popular house-shaped Bahnhäusleuhr ("railway-house clock") virtually forced the discontinuation of other styles within a few decades.

-

Lacquered shield cuckoo clock painted with roses, 19th century

Lacquered shield cuckoo clock painted with roses, 19th century

-

Picture frame timepiece, c. 1870. Enamel dial in a rectangular painting on a sheet metal: a hunter lies in wait for a hovering bird of prey, while two boys look at the tree stump in which the camouflage cuckoo's door is located (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 05–0962)

Picture frame timepiece, c. 1870. Enamel dial in a rectangular painting on a sheet metal: a hunter lies in wait for a hovering bird of prey, while two boys look at the tree stump in which the camouflage cuckoo's door is located (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 05–0962)

-

Biedermeier syle piece without the two columns at the front, second half 19th century

Biedermeier syle piece without the two columns at the front, second half 19th century

-

A neo-Baroque spring driven, mantel clock, attributed to Johann Baptist Beha, c. 1885. Original door missing (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 15–3833)

A neo-Baroque spring driven, mantel clock, attributed to Johann Baptist Beha, c. 1885. Original door missing (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 15–3833)

-

A neo-Renaissance example, dial with cartouches of Roman numerals, c. 1890 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 09–3936)

A neo-Renaissance example, dial with cartouches of Roman numerals, c. 1890 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 09–3936)

-

Castle-like ruins clock case with echo. There is a second smaller cuckoo partially visible in the sentry box at left, c. 1890 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 1995–638).

Castle-like ruins clock case with echo. There is a second smaller cuckoo partially visible in the sentry box at left, c. 1890 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 1995–638).

-

An eclectic style piece, combining Gothic and oriental decorative motifs, like the two dragons on its curved roof. Fürderer, Jaegler und Cie, Neustadt, c. 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07–3772)

An eclectic style piece, combining Gothic and oriental decorative motifs, like the two dragons on its curved roof. Fürderer, Jaegler und Cie, Neustadt, c. 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07–3772)

-

Another eclectic style example, case designed by Robert Bichweiler and crafted by Johann Winterhalder in Urach. The movement comes from Beha und Söhne in Eisenbach, 1885 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07–0325).

Another eclectic style example, case designed by Robert Bichweiler and crafted by Johann Winterhalder in Urach. The movement comes from Beha und Söhne in Eisenbach, 1885 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07–0325).

Bahnhäusle style, a successful design from Furtwangen

In September 1850, the first director of the Grand Duchy of Baden Clockmakers School in Furtwangen, Robert Gerwig, launched a public competition to submit designs for modern clockcases, which would allow homemade products to attain a professional appearance.

Friedrich Eisenlohr (1805–1854), who as an architect had been responsible for creating the buildings along the then new and first Badenese Rhine valley railway, submitted the most far-reaching design. Eisenlohr enhanced the facade of a standard railroad-guard's residence, as he had built many of them, with a clock dial. His "Wallclock with shield decorated by ivy vines", (in reality the ornament were grapevines and not ivy) as it is referred to in a surviving, handwritten report from the Clockmakers School from 1851 or 1852, became the prototype of today's popular souvenir cuckoo clocks.

Eisenlohr was also up-to-date stylistically. He was inspired by local images; rather than copying them slavishly, he modified them. Contrary to most present-day cuckoo clocks, his case features light, unstained wood and were decorated with symmetrical, flat fretwork ornaments. His idea became an instant hit, because the modern design of the Bahnhäusle clock appealed to the decorating tastes of the growing bourgeoisie and thereby tapped into new and growing markets.

While the Clockmakers School was satisfied to have Eisenlohr's clock case sketches, they were not fully realized in their original form. Eisenlohr had proposed a wooden facade; Gerwig preferred a painted metal front combined with an enamel dial. But despite intensive campaigns by the Clockmakers School, sheet metal fronts decorated with oil paintings (or coloured lithographs) never became a major market segment because of the high cost and labour-intensive process, hence they were only produced from the 1850s until around 1880, whether wall or mantel versions.

Characteristically, the makers of the first Bahnhäusle clocks deviated from Eisenlohr's sketch in only one way: they left out the cuckoo mechanism. Unlike today, the design with the little house was not synonymous with a cuckoo clock in the first years after 1850. This is another indication that at that time cuckoo clocks could not have been an important market segment.

Only in December 1854, Johann Baptist Beha, the best known maker of cuckoo clocks of his time, sold two of them, with oil paintings on their fronts, to the Furtwangen clock dealer Gordian Hettich, which were described as Bahnhöfle Uhren ("railway station clocks"). More than a year later, on 20 January 1856, another respected Furtwangen-based cuckoo clockmaker, Theodor Ketterer, sold one to Joseph Ruff in Glasgow.

Concurrently with Beha and Ketterer, other Black Forest clockmakers must have started to equip Bahnhäusle clocks with cuckoo mechanisms to satisfy the rapidly growing demand for this type of clock. Starting in the mid-1850s there was a real boom in this market. For example, numerous exhibitors at the trade exhibition in Villingen in 1858 offered cuckoo clocks in the Bahnhäuschenkasten or Bahnwartshaus. And in the annual report of the Furtwangen Clockmakers School of 1857/58 is stated: "The cuckoo clock therefore found a very special market again as soon as the Bahnhäuschen, which was so very suitable for it, was used as a clock case."

By 1862, Johann Baptist Beha started to enhance his richly decorated Bahnhäusle clocks with hands carved from bone and weights cast in the shape of fir cones. Even today this combination of elements is characteristic for cuckoo clocks, although the hands are usually made of wood or plastic, white celluloid was employed in the past too. As for the weights, there was during this second half of the 19th century, a few models which featured weights cast in the shape of a Gnome and other curious forms.

Thanks to Eisenlohr's design, the cuckoo clock became one of the most successful Black Forest products within a few years. In a report on the exhibition of local products at the 1873 Vienna World's Fair, Karl Schott, the then head of the Furtwanger Landesgewerbehalle (Furtwangen State Trade Hall), wrote "that today the cuckoo clock is one of the most sought-after clocks in the Black Forest". At the time of the Vienna exhibition, cuckoo clocks were not only sold on the German domestic market, but in many regions of the world. The main export countries in Europe were Switzerland, England, Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Schott also named overseas sales in his 1873 report: North America, Mexico, South America, Australia, India, Japan, China and even the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii).

By 1860, the Bahnhäusle style had started to develop away from its original, "severe" graphic form, and evolved toward the well-known case with three-dimensional woodcarvings, like the Jagdstück ("hunt piece", design created in Furtwangen in 1861), a cuckoo clock with a carved oak foliage and hunting motives, such as trophy animals, guns and powder pouches. Only ten years after its invention by Friedrich Eisenlohr, all variations of the house-theme had reached maturity. Bahnhäusle timepieces and its variations were also available as a mantel clock, but not as many compared to the wall version.

These ornate timepieces were not made by one clockmaker only, otherwise such a complex product could not have been produced at acceptable prices. There were numerous specialists who assisted the clockmakers. In 1873, Karl Schott reported on the division of labour at the Vienna Exhibition: "The birds are mostly carved and painted by women. The pipes are made by a pipe maker. In addition to a number of master craftsmen, there are also a number of large companies involved in the manufacture of cuckoo clocks, and the cuckoo clock maker rarely makes them himself. Rather, he obtains the movements, reworks them with precision, attaches the bellows and pipes and thus puts the finished movement in the case."

The division of labour meant that different clockmakers purchased completely identical parts from the same suppliers. Therefore, small components in particular, such as hands or dials, showed a tendency towards standardization. But it also happened from time to time that movements from different manufacturers were found in cases that looked the same on the outside, simply because they came from the same case maker.

The basic cuckoo clock of today is the railway-house (Bahnhäusle) form, still with its rich ornamentation, and these are known under the name of "carved", "classic" or "traditional"; which display carved leaves, birds, deer heads (Jagdstück design), other animals, etc. The richly decorated Bahnhäusle clocks have become a symbol of the Black Forest that is instantly understood anywhere in the world.

The cuckoo clock became successful and world-famous after Friedrich Eisenlohr contributed the Bahnhäusle design to the 1850 competition at the Furtwangen Clockmakers School.

-

A carved cuckoo and quail clock, c. 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07–2653)

A carved cuckoo and quail clock, c. 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07–2653)

-

Carved spring-driven, mantel clock with bone hands, Gordian Hettich Sohn, Furtwangen, c. 1870 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

Carved spring-driven, mantel clock with bone hands, Gordian Hettich Sohn, Furtwangen, c. 1870 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

-

Carved wall timepiece, weight-driven, Black Forest, c. 1900. Carved cuckoo clocks evolved from the Bahnhäusle style (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 2006–015).

Carved wall timepiece, weight-driven, Black Forest, c. 1900. Carved cuckoo clocks evolved from the Bahnhäusle style (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 2006–015).

-

Wood carvings composed of a vine with grapes, a bird on top, nest with eggs and parents and a matching pendulum bob (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

Wood carvings composed of a vine with grapes, a bird on top, nest with eggs and parents and a matching pendulum bob (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

-

Mantel clock with twisted columns and vines on their capitals, c. 1870 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

Mantel clock with twisted columns and vines on their capitals, c. 1870 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

-

Another variation from the Bahnhäusle style, here with Gothic motifs, c. 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 2012–036)

Another variation from the Bahnhäusle style, here with Gothic motifs, c. 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 2012–036)

Chalet style, the Swiss contribution

The chalet style cuckoo clock, whose case reproduce to scale a traditional farmhouse, originated in Switzerland in the late 19th century.

The miniature Swiss chalets date back to the beginnings of artistic wood carving in Brienz, in the early 19th century. The Brienzerware chalet became a popular souvenir, allowing tourists to take home an explicit reminder of a quintessential Swiss structure, though some were rather grand in scale, measuring three or more feet across. Many of these chalets, crafted in different sizes, doubled as music boxes, jewellery boxes, decorative objects, timepieces, etc. Some of those table clocks had also the added feature of a cuckoo bird or the tandem composed of a cuckoo and quail.

Eventually, Black Forest makers incorporated the chalet style to their production in the early 20th century, and still remains a popular choice, along with the carved ones, among buyers of this cult item. Cases are usually made after the traditional farmhouses of different regions, such as the Black Forest, Swiss Alps, Emmental, Bavaria and Tyrol. They often have a musical movement, as well as moving figurines and some other elements.

Contrary to popular belief, Switzerland is not the birthplace of the cuckoo clock. In the English-speaking world, cuckoo clocks are sufficiently identified with Switzerland that the 1949 film The Third Man has an oft-quoted speech (and it even had antecedents) in which the villainous Harry Lime mockingly says: " (...) in Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace - and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock."

In England

Bracket cuckoo clock by Higgs & Diego Evans, London, c. 1785. Left subsidiary dial with three selections: "CUCU Y TOCAR", "CUCU" and "TOCAR" (Spanish for strike), the right one with "MUSICA" and "SILENCIO". Lunette painted with a lakeside red brick English farmhouse with thatched roof. At the cuckoo's door is seen a farmer. In the image on the right, the simple wooden cuckoo above the movement, which has no moving beak and wings.

Bracket cuckoo clock by Higgs & Diego Evans, London, c. 1785. Left subsidiary dial with three selections: "CUCU Y TOCAR", "CUCU" and "TOCAR" (Spanish for strike), the right one with "MUSICA" and "SILENCIO". Lunette painted with a lakeside red brick English farmhouse with thatched roof. At the cuckoo's door is seen a farmer. In the image on the right, the simple wooden cuckoo above the movement, which has no moving beak and wings.

Apart from the Black Forest, the cuckoo clock was also made in England in the 18th century. It seems that very few of these London timepieces were produced, an indication that in those days, before the worldwide popularization of the cuckoo clock from the second half of the 19th century, there was not a high demand for them.

There is at least one example, intended for the Spanish market. It is a circa 1785 George III bracket clock, eight-day time, three-fusee, verge escapement, which announces the quarters on eight bells and gives the hours on a deep toned cuckoo, pull quarter repeat on command. The two pipes and bellows for the bird's sound are located at the base of the case, below the movement. Those pipes are placed horizontally, the same position seen in early Black Forest cuckoos. Both the dial and the elaborately engraved back plate, read: "Higgs y / Diego Evans / Londres".

Robert Higgs and his son Peter were in partnership together as Robert and Peter Higgs, and later, between 1780 and 1785 with James Evans, who sometimes styled himself in Spanish as Diego Evans. They traded musical and other complex clocks, many for the Spanish market.

In the mid-20th century, Camerer, Cuss & Co., London, a retailer of Black Forest clocks, etc., produced a few different models in the shape of a half-timbered Tudor style house. The bird was cast aluminum with movable beak and fixed wings and the weights were cylindrical, rather than pine-cone shaped. They were featured in a Pathé News newsreel in 1950.

According to author Terence Camerer Cuss, the company hoped to produce them in large quantities, but due to the high manufacturing cost, only fifty were made between 1949 and 1951. One of them, marked "01", was presented by the maker to the then Prince Charles in 1949 and is part of the Royal Collection.

In the United States

Cuckoo clocks have been imported to the US by German immigrants for a long time, especially in the 19th century. There are two well-known cuckoo clock manufacturers in the USA: The New England Cuckoo Clock Company was founded in 1958 by W. Kenneth Sessions Jr. and operated in Bristol, Connecticut. The design of the models is clearly American. The clocks were made with Hubert Herr clockworks that were imported from Triberg. The printed and colored paper dials of the clocks are unmistakable, as is the early American design. The clocks were designed by Nils Magnus Tornquist. A kit watch was also offered.

The second is the American Cuckoo Clock Company of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which originated in the 1890s and imported German clocks. Eventually, the company switched to importing clockworks only and building cuckoo clocks in the USA.

In Portugal and Brazil

In the 1940s and 50s cuckoo clocks were made in Portugal by Fábrica Nacional de Relógios A Boa Reguladora, Reguladora from 1953, in Vila Nova de Famalicão. Their models were in the Black Forest traditional style, with wood carved animals and leaves, and they could be spring-driven or weight-driven. Since its early years, the Portuguese clockmaking company was a fully integrated enterprise, making its own cases and movements (until 1995). In later catalogues, they sold cuckoos imported from Germany.

In Brazil, they were manufactured between the 1940s and the 1970s, marketed under different brand names such as Astro, Rei, H and Inrebra, the last two by INREBRA (Indústria de Relógios do Brasil Ltda.), São Paulo. Same as the Portuguese cuckoos, they were inspired by Black Forest models, with wood carvings or cases in the shape of a chalet.

In the Soviet Union and East Asia

Left: Majak cuckoo clock with a bakelite front decorated with spruce branches. Rami Garipov museum. Right: A Majak mechanical movement.

Left: Majak cuckoo clock with a bakelite front decorated with spruce branches. Rami Garipov museum. Right: A Majak mechanical movement.

From the early 1950s until the 1990s, cuckoo clocks were made in the former Soviet Union by the Serdobsk Clock Factory, which were sold under the trademark Маяк (transliterated as Majak) from 1963. They produced a range of models with a distinctive style; a colourful front painted with floral and vegetal motifs, spruce branches in relief, Russian motifs, basic decoration or any, a deer head on top, etc. One model in particular, composed of a bird on top and five wine leaves was directly based on a Black Forest one.

In Japan, its production began in 1949. Those early timepieces, in the Black Forest style, were marketed under the trademark Poppo by Tezuka Clock Co., Ltd., Tokyo, and usually had stamped "Made in Occupied Japan" on plate and dial. This term was used in items produced in the country between late 1945 and early 1952, after World War II.

In China and South Korea, cuckoo clocks also began to be manufactured in the second half of the 20th century.

Designer cuckoo clocks

The early 21st century has seen a revitalization of the iconic timepiece with designs, materials, technologies, shapes and colours never seen before in cuckoo clock manufacturing. These pieces are distinguished by its functional and minimalist aesthetic.

Although simplified designs with simple, clear lines had already been produced in the 20th century, the boom of designer cuckoo clocks was initiated in the 2000s (the first examples dating back to the 1990s), particularly in Italy, Germany and Japan.

There are a wide variety of models, many of them avant-garde creations made of different materials and geometric shapes, such as rhombuses, squares, cubes, circles, rectangles, etc. Without carving, these clocks are usually flat and smooth. Some are painted in a single colour while others are polychromes with abstract or figurative paintings, others include text and phrases, etc. About the clockwork, there are quartz, mechanical and sometimes, digital.

Museums

In Europe, museums that display collections are the Cuckooland Museum in the UK with more than 700 clocks, the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum and Dorf- und Uhrenmuseum Gütenbach in Germany.

The James J. Fiorentino Museum has one of the biggest collections in the United States. Located in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It contains more than 300 cuckoo clocks.

See also

- Automaton clock

- Black Forest Clock Association

- Cuckoo clock in culture

- List of largest cuckoo clocks

- Singing bird box

- Striking clock

References

- Peter Neville-Hadley (2016-04-03). "Germany's Black Forest clock route full of surprises". torontosun.com. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- Ross Sveback (2015-08-25). "Cuckoo for cuckoo clocks". fox9.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: The American Cuckoo Clock Company (2019-03-03), What Makes the Cuckoo Clock Bird Move?, retrieved 2019-03-24

- Stamp, Jimmy. "The Past, Present, and Future of the Cuckoo Clock". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- "1977 Citizen Wooden Cuckoo Clock, wedding gift (trans. from Japanese)". retroclock.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- "1979 Poppo cuckoo clock with the usual two bellows". lendhourvary.site (in Japanese). Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- For the early history of Black Forest clockmaking, see Gerd Bender, "Die Uhrenmacher des hohen Schwarzwaldes und ihre Werke". Vol. 1 (Villingen, 1975): pp. 1–10.

- ^ Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 646.

- Doering, Oscar (1901). "Des Augsburger Patriciers Philipp Hainhoffer Reisen nach Innsbruck und Dresden" (PDF). The Wagburg Institute. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- Graf, Johannes (2017-06-28). "Wer hat's erfunden? Zur Frühgeschichte der Kuckucksuhr (Who invented it? On the early history of the cuckoo clock)" (in German). blog.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- Inventory book of the Dresden Kunstkammer, 1619: "Darzu is ferner aufs neue einkommen 1 Uhr mit einem Kuckuck, so verüldt und schreiet Steht uf einem schwarz, von eubenenem holtz gemachten postamentlein uf der balbier lade" (Information provided by the Dresden State Art Collections)

- Athanasius Kircher, Musurgia Universalis sive Ars magna consoni & dissoni, 2 Vol (Rome, 1650), here Vol. 2, p. 343f and Plate XXI.

- Domenico Martinelli, Horologi Elementari (Venezia, 1669): p. 112.

- Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Document No.:"I.HA, Rep. 36, Nr. 3048, fol. 21f": "In another room, where the Dutch porcelain is kept, is a singing clock, which was made by a farmer in Kaschuben, which plays eight hymns; but the quarter hours are called out by a cuckoo". See also Claudia Sommer, Schloss Oranienburg. Ein Inventar aus dem Jahre 1743where there is also a reference to a currently missing inventory of 1709. The inventory of 1702 does not yet list this clock; therefore, it is probable that it reached Oranienburg between 1702 and 1709, Verwaltung der Märkischen Schlösser).

- It remains doubtful which is the oldest cuckoo clock before the bird made its appearance in the Black Forest. Again and again old iron or wooden clock movements are discovered, which have automated cuckoos that possibly predate the first wooden movement cuckoo clocks from the Black Forest. (See also Wilhelm Schneider, "Die eiserne Kuckucksuhr" (The Iron Movement Cuckoo Clock), Alte Uhren und Moderne Zeitmessung, No. 5 (1989): pp. 37–44).

- Also refer to the discussion on the origin of the Black Forest cuckoo clock to: Richard Mühe, Helmut Kahlert and Beatrice Techen, Kuckucksuhren (München, 1988): pp. 7–14.

- ^ "Die ersten Schwarzwälder Kuckucksuhren (Teil 1) (The First Black Forest Cuckoo Clocks (Part 1))" (in German). blog.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. 2017-07-13. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- Miller, Justin, Rare and Unusual Black Forest Clocks, (Schiffer 2012), p. 30.

- Helmut Kahlert, Die Kuckucksuhren-Saga, Alte Uhren, No. 4 (1983): pp. 347–353; here p. 349.

- "Rätsel um eine der ältesten Kuckucksuhren (Mystery about one of the oldest cuckoo clocks)" (in German). blog.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. 2021-12-01. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- Steyrer, Franz. "Geschichte der Schwarzwälder Uhrenmacherkunst" (in German). stegen-dreisamtal.de. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- Steyrer, Franz. "Geschichte der Schwarzwälder Uhrenmacherkunst (pp. 18-19)" (in German). Digital Collections Freiburg.University of Freiburg. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 647.

- ^ Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock: A Success Story. In: NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 651.

- ^ "Die ersten Schwarzwälder Kuckucksuhren (Teil 2) (The first Black Forest cuckoo clocks (Part 2))" (in German). blog.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. 2017-07-20. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- "Pier Van Leeuwen, "Clocks from the Black Forest (1740–1900)" (2005): in the Museum of the Dutch Clock website". Antique-horology.org. 2005-10-31. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ^ "Das Bahnhäusle – ein Jahrhundertdesign aus Furtwangen (Teil 1) (The Bahnhäusle – a design of the century from Furtwangen (Part 1))" (in German). blog.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. 2017-07-27. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- Beha cuckoo clock catalogue from ca. 1895 shows two different models in the Biedermeier style in page 5

- "The Richards' Collection". antiquecuckooclock.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ^ Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. In: NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 649.

- The credit for first discovering Eisenlohr's original design goes to Herbert Jüttemann. See Herbert Jüttemann, Die Schwarzwalduhr, 4th ed. (Karlsruhe, 2000): p. 242.

- Verzeichniss der von Künstlern und Kunstfreunden, der Ghz. Uhrenmacherschule, zugekommenen Entwürfe, zu Uhr-Schilden und Gehäusen (List of the Designs submitted by artists and friends of the arts to the Furtwangen Clockmaking School for 1850-51). Undated manuscript (probably 1851 or 1852) (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum Furtwangen, Archive)

- Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 648.

- Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 649.

- Wilhelm Schneider "Frühe Kuckucksuhren von Johann Baptist Beha aus Eisenbach im Hochschwarzwald" (Remembering the design of a genius. 150 years of Bahnhaeusle clocks), Alte Uhren und moderne Zeitmessung, No. 3 (1987): pp. 45–53, here p. 51.

- "Kuckucksuhr, mon amour" (PDF) (in German). 2013. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- As per Wilhelm Schneider, who had a chance to examine the account books of Beha. See Wilhelm Schneider, "Frühe Kuckucksuhren von Johann Baptist aus Eisenbach im Hochschwarzwald" (Early cuckoo clocks by Johann Baptist Beha of Eisenbach in the high Black Forest). Alte Uhren und moderne Zeitmessung. No 3 (1987): pp. 45–53, here p. 52.

- ^ "Das Bahnhäusle – ein Jahrhundertdesign aus Furtwangen (Teil 2) (The Bahnhäusle – a design of the century from Furtwangen (Part 2))" (in German). blog.deutsches-uhrenmuseum.de. 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- Schneider 1987, p. 51. (Within a short time more orders for hunt pieces are recorded, specifically on October 30, November 7 and November 26, 1861.)

- ^ Robert Brookes (24 November 2006). "Going cuckoo about real Swiss cuckoo clocks". Berne, Switzerland: SWI swissinfo.ch, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation SRG SSR. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Peter F. Blackman, The Black Forest Woodcarvings (2009): p. 33

- Peter F. Blackman, The Black Forest Woodcarvings (2009): p. 271

- "Swiss cuckoo and quail clock, 1880s". 1stdibs.com (in French). Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- "Diego Evans Shelf Clock (London, England)". garysullivanantiques.com. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- "Lot 200: C. 1785, Diego Evans & Peter Higgs, London". Invaluable.com. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- "Mahogany Quarter-Chiming Spanish Market Bracket Clock with Automaton by David Evans". Skinner. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- Huete, Amelia Aranda. "Diego Evans" (in Spanish). Colección Banco de España. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- "English-made cuckoo clock". NAWCC.org. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- "Cuckoo clocks". British Pathé. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- "Camerer & Cuss cuckoo clock". NAWCC.org. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- "Cuckoo Clock". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- Boyett, David. "American Cuckoo Clock Co PA—Knierman Family". PBase. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- "Cuckoo Clock". Senator John Heinz History Center. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- "Relógio de cuco [back label dated 13th January 1950]" (in Portuguese). Leiloeira Serralves. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- "A Boa Reguladora" (in Portuguese). restosdecoleccao.blogspot. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Correia de Oliveira, Fernando. "Memória - A saga dos relógios de A Boa Reguladora" (in Portuguese). estacaochronographica.blogspot. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Fernando Correia de Oliveria, A Boa Reguladora-Uma Viagen no Tempo, Internacional Horas & Relógios, Juhlo/Agosto 2004: p. 25.

- Correia de Oliveira, Fernando. "Há dez anos... A Boa Reguladora realizava última exposição histórica dos seus relógios" (in Portuguese). estacaochronographica.blogspot. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Correia de Oliveira, Fernando. "Catálogos antigos dos relógios Reguladora" (in Portuguese). estacaochronographica.blogspot. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- "Cuckoo clock from 1948 made in Brazil-(Cuco H Brasileiro)". Youtube. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- "Relógio Cuco "H" Inrebra 202.Ano aproximado de fabricação 1975". wilsonpontual33.blogspot (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- "Relógio de parede "cuco" da marca "inrebra"". leilaobaronesa.com (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- "SCZ". ussr-watch.com (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "The History of Serdobsk Clock Factory". oldserdobsk.ru. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "Poppo Musical Cuckoo Clock". nawccc.org. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ^ "Juan F. Déniz, Designer Cuckoo Clocks. In: NAWCC Bulletin, September/October 2013: p. 479" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- Carlson, Leland (2015). Dull Men of Great Britain: Celebrating the Ordinary. Ebury Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-78503-090-1.

Cuckooland has more than 700 cuckoo clocks on display, each one different from the others.

- Marsh, Steve (May 12, 2015). "In Search of Lost Time". Mpls.St.Paul magazine. Accessed 14 December 2021.

General bibliography

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1985): "Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Kuckucksuhr". In: Alte Uhren, Fascicle 3, pp. 13–21.

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1987): "Frühe Kuckucksuhren von Johann Baptist Beha in Eisenbach im Hochschwarzwald". In: Uhren, Fascicle 3, pp. 45–53.

- Mühe, Richard, Kahlert, Helmut and Techen, "Beatrice" (1988): Kuckucksuhren. München.

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1988): "The Cuckoo Clocks of Johann Baptist Beha". In: Antiquarian Horology, Vol. 17, pp. 455–462.

- Schneider, Wilhelm, Schneider, Monika (1988): "Black Forest Cuckoo Clocks at the Exhibitions in Philadelphia 1876 and Chicago 1893". In: Watch & Clock Bulletin, Vol. 30/2, No. 253, pp. 116–127 and 128–132.

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1989): "Die eiserne Kuckucksuhr". In: Uhren, 12. Jg., Fascicle 5, pp. 37–44.

- Kahlert, Helmut (2002): "Erinnerung an ein geniales Design. 150 Jahre Bahnhäusle-Uhren". In: Klassik-Uhren, F. 4, pp. 26–30.

- Graf, Johannes (December 2006): "The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock: A Success Story". In: Watch & Clock Bulletin. Volume 49, Issue 365. pp. 646–652.

- Miller, Justin (2012). Rare and Unusual Black Forest Clocks. Atglen, Penn.: Schiffer Pub. ISBN 9780764340918. OCLC 768166840. pp. 27–103.

- Scholz, Julia (2013): Kuckucksuhr Mon Amour. Faszination Schwarzwalduhr. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag, 160 p. ISBN 978-3-8062-2797-0.

External links

- Article on Designer Cuckoo Clocks published in the NAWCC bulletin

- Catalogue of Philipp Haas & Söhne (PHS), St. Georgen 1880 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum)

- Cuckooland Museum, a museum devoted to the cuckoo clock

- German clock and watch museum

- Dorf und Uhrenmuseum