| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

| Second law of motion |

| Branches |

| Fundamentals |

| Formulations |

| Core topics |

| Rotation |

| Scientists |

In classical mechanics, a harmonic oscillator is a system that, when displaced from its equilibrium position, experiences a restoring force F proportional to the displacement x: where k is a positive constant.

If F is the only force acting on the system, the system is called a simple harmonic oscillator, and it undergoes simple harmonic motion: sinusoidal oscillations about the equilibrium point, with a constant amplitude and a constant frequency (which does not depend on the amplitude).

If a frictional force (damping) proportional to the velocity is also present, the harmonic oscillator is described as a damped oscillator. Depending on the friction coefficient, the system can:

- Oscillate with a frequency lower than in the undamped case, and an amplitude decreasing with time (underdamped oscillator).

- Decay to the equilibrium position, without oscillations (overdamped oscillator).

The boundary solution between an underdamped oscillator and an overdamped oscillator occurs at a particular value of the friction coefficient and is called critically damped.

If an external time-dependent force is present, the harmonic oscillator is described as a driven oscillator.

Mechanical examples include pendulums (with small angles of displacement), masses connected to springs, and acoustical systems. Other analogous systems include electrical harmonic oscillators such as RLC circuits. The harmonic oscillator model is very important in physics, because any mass subject to a force in stable equilibrium acts as a harmonic oscillator for small vibrations. Harmonic oscillators occur widely in nature and are exploited in many manmade devices, such as clocks and radio circuits. They are the source of virtually all sinusoidal vibrations and waves.

Simple harmonic oscillator

Main article: Simple harmonic motion Mass-spring harmonic oscillator

Mass-spring harmonic oscillator Simple harmonic motion

Simple harmonic motion

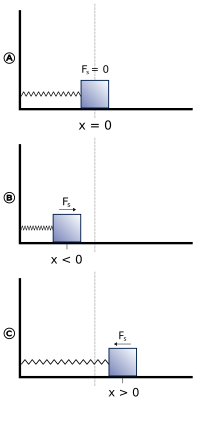

A simple harmonic oscillator is an oscillator that is neither driven nor damped. It consists of a mass m, which experiences a single force F, which pulls the mass in the direction of the point x = 0 and depends only on the position x of the mass and a constant k. Balance of forces (Newton's second law) for the system is

Solving this differential equation, we find that the motion is described by the function where

The motion is periodic, repeating itself in a sinusoidal fashion with constant amplitude A. In addition to its amplitude, the motion of a simple harmonic oscillator is characterized by its period , the time for a single oscillation or its frequency , the number of cycles per unit time. The position at a given time t also depends on the phase φ, which determines the starting point on the sine wave. The period and frequency are determined by the size of the mass m and the force constant k, while the amplitude and phase are determined by the starting position and velocity.

The velocity and acceleration of a simple harmonic oscillator oscillate with the same frequency as the position, but with shifted phases. The velocity is maximal for zero displacement, while the acceleration is in the direction opposite to the displacement.

The potential energy stored in a simple harmonic oscillator at position x is

Damped harmonic oscillator

Main article: Damping

In real oscillators, friction, or damping, slows the motion of the system. Due to frictional force, the velocity decreases in proportion to the acting frictional force. While in a simple undriven harmonic oscillator the only force acting on the mass is the restoring force, in a damped harmonic oscillator there is in addition a frictional force which is always in a direction to oppose the motion. In many vibrating systems the frictional force Ff can be modeled as being proportional to the velocity v of the object: Ff = −cv, where c is called the viscous damping coefficient.

The balance of forces (Newton's second law) for damped harmonic oscillators is then which can be rewritten into the form where

- is called the "undamped angular frequency of the oscillator",

- is called the "damping ratio".

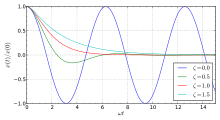

The value of the damping ratio ζ critically determines the behavior of the system. A damped harmonic oscillator can be:

- Overdamped (ζ > 1): The system returns (exponentially decays) to steady state without oscillating. Larger values of the damping ratio ζ return to equilibrium more slowly.

- Critically damped (ζ = 1): The system returns to steady state as quickly as possible without oscillating (although overshoot can occur if the initial velocity is nonzero). This is often desired for the damping of systems such as doors.

- Underdamped (ζ < 1): The system oscillates (with a slightly different frequency than the undamped case) with the amplitude gradually decreasing to zero. The angular frequency of the underdamped harmonic oscillator is given by the exponential decay of the underdamped harmonic oscillator is given by

The Q factor of a damped oscillator is defined as

Q is related to the damping ratio by

Driven harmonic oscillators

Driven harmonic oscillators are damped oscillators further affected by an externally applied force F(t).

Newton's second law takes the form

It is usually rewritten into the form

This equation can be solved exactly for any driving force, using the solutions z(t) that satisfy the unforced equation

and which can be expressed as damped sinusoidal oscillations: in the case where ζ ≤ 1. The amplitude A and phase φ determine the behavior needed to match the initial conditions.

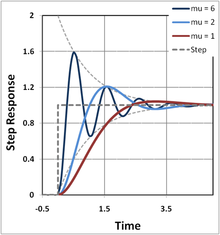

Step input

See also: Step responseIn the case ζ < 1 and a unit step input with x(0) = 0: the solution is

with phase φ given by

The time an oscillator needs to adapt to changed external conditions is of the order τ = 1/(ζω0). In physics, the adaptation is called relaxation, and τ is called the relaxation time.

In electrical engineering, a multiple of τ is called the settling time, i.e. the time necessary to ensure the signal is within a fixed departure from final value, typically within 10%. The term overshoot refers to the extent the response maximum exceeds final value, and undershoot refers to the extent the response falls below final value for times following the response maximum.

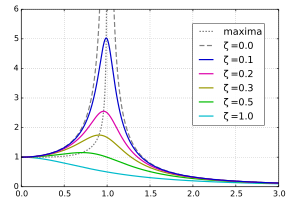

Sinusoidal driving force

In the case of a sinusoidal driving force: where is the driving amplitude, and is the driving frequency for a sinusoidal driving mechanism. This type of system appears in AC-driven RLC circuits (resistor–inductor–capacitor) and driven spring systems having internal mechanical resistance or external air resistance.

The general solution is a sum of a transient solution that depends on initial conditions, and a steady state that is independent of initial conditions and depends only on the driving amplitude , driving frequency , undamped angular frequency , and the damping ratio .

The steady-state solution is proportional to the driving force with an induced phase change : where is the absolute value of the impedance or linear response function, and

is the phase of the oscillation relative to the driving force. The phase value is usually taken to be between −180° and 0 (that is, it represents a phase lag, for both positive and negative values of the arctan argument).

For a particular driving frequency called the resonance, or resonant frequency , the amplitude (for a given ) is maximal. This resonance effect only occurs when , i.e. for significantly underdamped systems. For strongly underdamped systems the value of the amplitude can become quite large near the resonant frequency.

The transient solutions are the same as the unforced () damped harmonic oscillator and represent the systems response to other events that occurred previously. The transient solutions typically die out rapidly enough that they can be ignored.

Parametric oscillators

Main article: Parametric oscillatorA parametric oscillator is a driven harmonic oscillator in which the drive energy is provided by varying the parameters of the oscillator, such as the damping or restoring force. A familiar example of parametric oscillation is "pumping" on a playground swing. A person on a moving swing can increase the amplitude of the swing's oscillations without any external drive force (pushes) being applied, by changing the moment of inertia of the swing by rocking back and forth ("pumping") or alternately standing and squatting, in rhythm with the swing's oscillations. The varying of the parameters drives the system. Examples of parameters that may be varied are its resonance frequency and damping .

Parametric oscillators are used in many applications. The classical varactor parametric oscillator oscillates when the diode's capacitance is varied periodically. The circuit that varies the diode's capacitance is called the "pump" or "driver". In microwave electronics, waveguide/YAG based parametric oscillators operate in the same fashion. The designer varies a parameter periodically to induce oscillations.

Parametric oscillators have been developed as low-noise amplifiers, especially in the radio and microwave frequency range. Thermal noise is minimal, since a reactance (not a resistance) is varied. Another common use is frequency conversion, e.g., conversion from audio to radio frequencies. For example, the Optical parametric oscillator converts an input laser wave into two output waves of lower frequency ().

Parametric resonance occurs in a mechanical system when a system is parametrically excited and oscillates at one of its resonant frequencies. Parametric excitation differs from forcing, since the action appears as a time varying modification on a system parameter. This effect is different from regular resonance because it exhibits the instability phenomenon.

Universal oscillator equation

The equation is known as the universal oscillator equation, since all second-order linear oscillatory systems can be reduced to this form. This is done through nondimensionalization.

If the forcing function is f(t) = cos(ωt) = cos(ωtcτ) = cos(ωτ), where ω = ωtc, the equation becomes

The solution to this differential equation contains two parts: the "transient" and the "steady-state".

Transient solution

The solution based on solving the ordinary differential equation is for arbitrary constants c1 and c2

The transient solution is independent of the forcing function.

Steady-state solution

Apply the "complex variables method" by solving the auxiliary equation below and then finding the real part of its solution:

Supposing the solution is of the form

Its derivatives from zeroth to second order are

Substituting these quantities into the differential equation gives

Dividing by the exponential term on the left results in

Equating the real and imaginary parts results in two independent equations

Amplitude part

Squaring both equations and adding them together gives

Therefore,

Compare this result with the theory section on resonance, as well as the "magnitude part" of the RLC circuit. This amplitude function is particularly important in the analysis and understanding of the frequency response of second-order systems.

Phase part

To solve for φ, divide both equations to get

This phase function is particularly important in the analysis and understanding of the frequency response of second-order systems.

Full solution

Combining the amplitude and phase portions results in the steady-state solution

The solution of original universal oscillator equation is a superposition (sum) of the transient and steady-state solutions:

Equivalent systems

Main article: System equivalenceHarmonic oscillators occurring in a number of areas of engineering are equivalent in the sense that their mathematical models are identical (see universal oscillator equation above). Below is a table showing analogous quantities in four harmonic oscillator systems in mechanics and electronics. If analogous parameters on the same line in the table are given numerically equal values, the behavior of the oscillators – their output waveform, resonant frequency, damping factor, etc. – are the same.

| Translational mechanical | Rotational mechanical | Series RLC circuit | Parallel RLC circuit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Angle | Charge | Flux linkage |

| Velocity | Angular velocity | Current | Voltage |

| Mass | Moment of inertia | Inductance | Capacitance |

| Momentum | Angular momentum | Flux linkage | Charge |

| Spring constant | Torsion constant | Elastance | Magnetic reluctance |

| Damping | Rotational friction | Resistance | Conductance |

| Drive force | Drive torque | Voltage | Current |

| Undamped resonant frequency : | |||

| Damping ratio : | |||

| Differential equation: | |||

Application to a conservative force

The problem of the simple harmonic oscillator occurs frequently in physics, because a mass at equilibrium under the influence of any conservative force, in the limit of small motions, behaves as a simple harmonic oscillator.

A conservative force is one that is associated with a potential energy. The potential-energy function of a harmonic oscillator is

Given an arbitrary potential-energy function , one can do a Taylor expansion in terms of around an energy minimum () to model the behavior of small perturbations from equilibrium.

Because is a minimum, the first derivative evaluated at must be zero, so the linear term drops out:

The constant term V(x0) is arbitrary and thus may be dropped, and a coordinate transformation allows the form of the simple harmonic oscillator to be retrieved:

Thus, given an arbitrary potential-energy function with a non-vanishing second derivative, one can use the solution to the simple harmonic oscillator to provide an approximate solution for small perturbations around the equilibrium point.

Examples

Simple pendulum

Assuming no damping, the differential equation governing a simple pendulum of length , where is the local acceleration of gravity, is

If the maximal displacement of the pendulum is small, we can use the approximation and instead consider the equation

The general solution to this differential equation is where and are constants that depend on the initial conditions. Using as initial conditions and , the solution is given by where is the largest angle attained by the pendulum (that is, is the amplitude of the pendulum). The period, the time for one complete oscillation, is given by the expression which is a good approximation of the actual period when is small. Notice that in this approximation the period is independent of the amplitude . In the above equation, represents the angular frequency.

Spring/mass system

When a spring is stretched or compressed by a mass, the spring develops a restoring force. Hooke's law gives the relationship of the force exerted by the spring when the spring is compressed or stretched a certain length: where F is the force, k is the spring constant, and x is the displacement of the mass with respect to the equilibrium position. The minus sign in the equation indicates that the force exerted by the spring always acts in a direction that is opposite to the displacement (i.e. the force always acts towards the zero position), and so prevents the mass from flying off to infinity.

By using either force balance or an energy method, it can be readily shown that the motion of this system is given by the following differential equation: the latter being Newton's second law of motion.

If the initial displacement is A, and there is no initial velocity, the solution of this equation is given by

Given an ideal massless spring, is the mass on the end of the spring. If the spring itself has mass, its effective mass must be included in .

Energy variation in the spring–damping system

In terms of energy, all systems have two types of energy: potential energy and kinetic energy. When a spring is stretched or compressed, it stores elastic potential energy, which is then transferred into kinetic energy. The potential energy within a spring is determined by the equation

When the spring is stretched or compressed, kinetic energy of the mass gets converted into potential energy of the spring. By conservation of energy, assuming the datum is defined at the equilibrium position, when the spring reaches its maximal potential energy, the kinetic energy of the mass is zero. When the spring is released, it tries to return to equilibrium, and all its potential energy converts to kinetic energy of the mass.

Definition of terms

| Symbol | Definition | Dimensions | SI units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceleration of mass | m/s | ||

| Peak amplitude of oscillation | m | ||

| Viscous damping coefficient | N·s/m | ||

| Frequency | Hz | ||

| Drive force | N | ||

| Acceleration of gravity at the Earth's surface | m/s | ||

| Imaginary unit, | — | — | |

| Spring constant | N/m | ||

| Torsion Spring constant | Nm/rad | ||

| Mass | kg | ||

| Quality factor | — | — | |

| Period of oscillation | s | ||

| Time | s | ||

| Potential energy stored in oscillator | J | ||

| Position of mass | m | ||

| Damping ratio | — | — | |

| Phase shift | — | rad | |

| Angular frequency | rad/s | ||

| Natural resonant angular frequency | rad/s |

See also

- Anharmonicity

- Critical speed

- Effective mass (spring–mass system)

- Fradkin tensor

- Normal mode

- Parametric oscillator

- Phasor

- Q factor

- Quantum harmonic oscillator

- Radial harmonic oscillator

- Elastic pendulum

Notes

- Fowles & Cassiday (1986, p. 86)

- Kreyszig (1972, p. 65)

- Tipler (1998, pp. 369, 389)

- Case, William. "Two ways of driving a child's swing". Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Case, W. B. (1996). "The pumping of a swing from the standing position". American Journal of Physics. 64 (3): 215–220. Bibcode:1996AmJPh..64..215C. doi:10.1119/1.18209.

- Roura, P.; Gonzalez, J.A. (2010). "Towards a more realistic description of swing pumping due to the exchange of angular momentum". European Journal of Physics. 31 (5): 1195–1207. Bibcode:2010EJPh...31.1195R. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/31/5/020. S2CID 122086250.

References

- Fowles, Grant R.; Cassiday, George L. (1986), Analytic Mechanics (5th ed.), Fort Worth: Saunders College Publishing, ISBN 0-03-089725-4, LCCN 93085193

- Hayek, Sabih I. (15 Apr 2003). "Mechanical Vibration and Damping". Encyclopedia of Applied Physics. WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co KGaA. doi:10.1002/3527600434.eap231. ISBN 9783527600434.

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1972), Advanced Engineering Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-50728-8

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2003). Physics for Scientists and Engineers. Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

- Tipler, Paul (1998). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Vol. 1 (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 1-57259-492-6.

- Wylie, C. R. (1975). Advanced Engineering Mathematics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-072180-7.

External links

, the time for a single oscillation or its frequency

, the time for a single oscillation or its frequency  , the number of cycles per unit time. The position at a given time t also depends on the

, the number of cycles per unit time. The position at a given time t also depends on the

which can be rewritten into the form

which can be rewritten into the form

where

where

is called the "undamped

is called the "undamped

the

the

in the case where ζ ≤ 1. The amplitude A and phase φ determine the behavior needed to match the initial conditions.

in the case where ζ ≤ 1. The amplitude A and phase φ determine the behavior needed to match the initial conditions.

the solution is

the solution is

and damping

and damping  of a driven harmonic oscillator. This plot is also called the harmonic oscillator spectrum or motional spectrum.

of a driven harmonic oscillator. This plot is also called the harmonic oscillator spectrum or motional spectrum. where

where  is the driving amplitude, and

is the driving amplitude, and  is the driving

is the driving  , and the damping ratio

, and the damping ratio  :

:

where

where

, the amplitude (for a given

, the amplitude (for a given  , i.e. for significantly underdamped systems. For strongly underdamped systems the value of the amplitude can become quite large near the resonant frequency.

, i.e. for significantly underdamped systems. For strongly underdamped systems the value of the amplitude can become quite large near the resonant frequency.

) damped harmonic oscillator and represent the systems response to other events that occurred previously. The transient solutions typically die out rapidly enough that they can be ignored.

) damped harmonic oscillator and represent the systems response to other events that occurred previously. The transient solutions typically die out rapidly enough that they can be ignored.

.

.

).

).

is known as the universal oscillator equation, since all second-order linear oscillatory systems can be reduced to this form. This is done through

is known as the universal oscillator equation, since all second-order linear oscillatory systems can be reduced to this form. This is done through

:

:

, one can do a

, one can do a  ) to model the behavior of small perturbations from equilibrium.

) to model the behavior of small perturbations from equilibrium.

is a minimum, the first derivative evaluated at

is a minimum, the first derivative evaluated at  must be zero, so the linear term drops out:

must be zero, so the linear term drops out:

, where

, where  is the local

is the local

and instead consider the equation

and instead consider the equation

where

where  and

and  and

and  , the solution is given by

, the solution is given by

where

where  is the largest angle attained by the pendulum (that is,

is the largest angle attained by the pendulum (that is,

is independent of the amplitude

is independent of the amplitude  where F is the force, k is the spring constant, and x is the displacement of the mass with respect to the equilibrium position. The minus sign in the equation indicates that the force exerted by the spring always acts in a direction that is opposite to the displacement (i.e. the force always acts towards the zero position), and so prevents the mass from flying off to infinity.

where F is the force, k is the spring constant, and x is the displacement of the mass with respect to the equilibrium position. The minus sign in the equation indicates that the force exerted by the spring always acts in a direction that is opposite to the displacement (i.e. the force always acts towards the zero position), and so prevents the mass from flying off to infinity.

the latter being

the latter being