| First Chechen War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chechen–Russian conflict and post-Soviet conflicts | |||||

A Russian Mil Mi-8 helicopter brought down by Chechen fighters near the Chechen capital of Grozny in 1994. | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

Foreign volunteers: |

| ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Strength | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

|

Official estimates: 3,000 (Chechen estimate) 3,000+ (Russian military data) Independent estimates: Approx. 3,000+ killed (Nezavisimaya Gazeta) 3,000 killed (Memorial) |

Russian estimate: 5,552 soldiers killed or missing 16,098-18,000 wounded Independent estimates: 14,000 killed (CSMR) 9,000+ killed or missing. Up to 52,000 wounded (Time) | ||||

|

100,000–130,000 civilians killed (Bonner) 80,000–100,000 civilians killed (Human rights groups estimate) 30,000–40,000+ civilians killed (RFSSS data) At least 161 civilians killed outside Chechnya 500,000+ civilians displaced | |||||

| First Chechen War | |

|---|---|

| Pre-war battles

1994–1995

1996 |

| Post-Soviet conflicts | |

|---|---|

|

| Terrorism in Russia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chechen–Russian conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

The First Chechen War, also referred to as the First Russo-Chechen War, was a struggle for independence waged by the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria against the Russian Federation from 11 December 1994 to 31 August 1996. This conflict was preceded by the battle of Grozny in November 1994, during which Russia covertly sought to overthrow the new Chechen government. Following the intense Battle of Grozny in 1994–1995, which concluded with a victory for the Russian federal forces, Russia's subsequent efforts to establish control over the remaining lowlands and mountainous regions of Chechnya were met with fierce resistance and frequent surprise raids by Chechen guerrillas. The recapture of Grozny in 1996 played a part in the Khasavyurt Accord (ceasefire), and the signing of the 1997 Russia–Chechnya Peace Treaty.

The official Russian estimate of Russian military deaths was 6,000, but according to other estimates, the number of Russian military deaths was as high as 14,000. According to various estimates, the number of Chechen military deaths was approximately 3,000–10,000, the number of Chechen civilian deaths was between 30,000 and 100,000. Over 200,000 Chechen civilians may have been injured, more than 500,000 people were displaced, and cities and villages were reduced to rubble across the republic.

Origins

Main article: Chechen–Russian conflictChechnya within Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union

Chechen resistance against Russian imperialism has its origins from 1785 during the time of Sheikh Mansur, the first imam (leader) of the Caucasian peoples. He united various North-Caucasian nations under his command to resist Russian invasions and expansion.

Following long local resistance during the 1817–1864 Caucasian War, Imperial Russian forces defeated the Chechens and annexed their lands and deported thousands to the Middle East in the latter part of the 19th century. The Chechens' subsequent attempts at gaining independence after the 1917 fall of the Russian Empire failed, and in 1922 Chechnya became part of Soviet Russia and in December 1922 part of the newly formed Soviet Union (USSR). In 1936, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin established the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, within the Russian SFSR.

In 1944, on the orders of NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria, more than 500,000 Chechens, the Ingush and several other North Caucasian people were ethnically cleansed and deported to Siberia and to Central Asia. The official pretext was punishment for collaboration with the invading German forces during the 1940–1944 insurgency in Chechnya, despite the fact that many Chechens and Ingush were loyal to the Soviet government and fought against the Nazis and they even received the highest military awards in the Soviet Union (e.g. Khanpasha Nuradilov and Movlid Visaitov). In March 1944, the Soviet authorities abolished the Checheno-Ingush Republic. Eventually, Soviet first secretary Nikita Khrushchev granted the Vainakh (Chechen and Ingush) peoples permission to return to their homeland and he restored their republic in 1957.

Dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation Treaty

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Russia became an independent state after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991. The Russian Federation was widely accepted as the successor state to the USSR, but it lost a significant amount of its military and economic power. Ethnic Russians made up more than 80% of the population of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, but significant ethnic and religious differences posed a threat of political disintegration in some regions. In the Soviet period, some of Russia's approximately 100 nationalities were granted ethnic enclaves that had various formal federal rights attached. Relations of these entities with the federal government and demands for autonomy erupted into a major political issue in the early 1990s. Boris Yeltsin incorporated these demands into his 1990 election campaign by claiming that their resolution was a high priority.

There was an urgent need for a law to clearly define the powers of each federal subject. Such a law was passed on 31 March 1992, when Yeltsin and Ruslan Khasbulatov, then chairman of the Russian Supreme Soviet and an ethnic Chechen himself, signed the Federation Treaty bilaterally with 86 out of 88 federal subjects. In almost all cases, demands for greater autonomy or independence were satisfied by concessions of regional autonomy and tax privileges. The treaty outlined three basic types of federal subjects and the powers that were reserved for local and federal government. The only federal subjects that did not sign the treaty were Chechnya and Tatarstan. Eventually, in early 1994, Yeltsin signed a special political accord with Mintimer Shaeymiev, the president of Tatarstan, granting many of its demands for greater autonomy for the republic within Russia. Thus, Chechnya remained the only federal subject that did not sign the treaty. Neither Yeltsin nor the Chechen government attempted any serious negotiations and the situation deteriorated into a full-scale conflict.

Chechen declaration of independence

Meanwhile, on 6 September 1991, militants of the All-National Congress of the Chechen People (NCChP) party, created by the former Soviet Air Force general Dzhokhar Dudayev, stormed a session of the Supreme Soviet of the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, with the aim of asserting independence. The storming caused the death of the head of Grozny's branch of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Vitaliy Kutsenko, who was defenestrated or fell while trying to escape. This effectively dissolved the government of the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Republic of the Soviet Union.

Elections for the president and parliament of Chechnya were held on 27 October 1991. The day before, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union published a notice in the local Chechen press that the elections were illegal. With a turnout of 72%, 90.1% voted for Dudayev.

Dudayev won overwhelming popular support (as evidenced by the later presidential elections with high turnout and a clear Dudayev victory) to oust the interim administration supported by the central government. He became president and declared independence from the Soviet Union.

In November 1991, Yeltsin dispatched Internal Troops to Grozny, but they were forced to withdraw when Dudayev's forces surrounded them at the airport. After Chechnya made its initial declaration of sovereignty, the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Republic split in two in June 1992 amidst the armed conflict between the Ingush and Ossetians. The newly created Republic of Ingushetia then joined the Russian Federation, while Chechnya declared full independence from Moscow in 1993 as the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI).

Internal conflict in Chechnya and the Grozny–Moscow tensions

The economy of Chechnya collapsed as Dudayev severed economic links with Russia while black market trading, arms trafficking and counterfeiting grew. Violence and social disruption increased and the marginal social groups, such as unemployed young men from the countryside, became armed. Ethnic Russians and other non-Chechens faced constant harassment as they fell outside the vendetta system which protected the Chechens to a certain extent. From 1991 to 1994, tens of thousands of people of non-Chechen ethnicity left the republic.

During the undeclared Chechen civil war, factions both sympathetic and opposed to Dzhokhar Dudayev fought for power, sometimes in pitched battles with the use of heavy weapons. In March 1993, the opposition attempted a coup d'état, but their attempt was crushed by force. A month later, Dudayev introduced direct presidential rule, and in June 1993 dissolved the Chechen parliament to avoid a referendum on a vote of non-confidence. In late October 1992, Russian forces dispatched to the zone of the Ossetian-Ingush conflict were ordered to move to the Chechen border; Dudayev, who perceived this as "an act of aggression against the Chechen Republic", declared a state of emergency and threatened general mobilization if the Russian troops did not withdraw from the Chechen border. To prevent the invasion of Chechnya, he did not provoke the Russian troops.

After staging another coup d'état attempt in December 1993, the opposition organized themselves into the Provisional Council of the Chechen Republic as a potential alternative government for Chechnya, calling on Moscow for assistance. In August 1994, the coalition of the opposition factions based in north Chechnya launched a large-scale armed campaign to remove Dudayev's government.

However, the issue of contention was not independence from Russia: even the opposition stated there was no alternative to an international boundary separating Chechnya from Russia. In 1992, Russian newspaper Moscow News noted that, just like most of the other seceding republics, other than Tatarstan, ethnic Chechens universally supported the establishment of an independent Chechen state and, in 1995, during the heat of the First Chechen War, Khalid Delmayev, a Dudayev opponent belonging to an Ichkerian liberal coalition, stated that "Chechnya's statehood may be postponed... but cannot be avoided".

Moscow covertly supplied opposition forces with finances, military equipment and mercenaries. Russia also suspended all civilian flights to Grozny while the aviation and border troops established a military blockade of the republic, and eventually unmarked Russian aircraft began combat operations over Chechnya. The opposition forces, who were joined by Russian troops, launched a poorly organized assault on Grozny in mid-October 1994, followed by a second, larger attack on 26–27 November 1994. Despite Russian support, both attempts were unsuccessful. Chechen separatists succeeded in capturing some 20 Russian Ground Forces regulars and about 50 other Russian citizens who were covertly hired by the Russian FSK state security organization (which was later converted to the FSB) to fight for the Provisional Council forces. On 29 November, President Boris Yeltsin issued an ultimatum to all warring factions in Chechnya, ordering them to disarm and surrender. When the government in Grozny refused, Yeltsin ordered the Russian army to invade the region. Both the Russian government and military command never referred to the conflict as a war but instead a 'disarmament of illegal gangs' or a 'restoration of the constitutional order'.

Beginning on 1 December, Russian forces openly carried out heavy aerial bombardments of Chechnya. On 11 December 1994, five days after Dudayev and Russian Minister of Defense Gen. Pavel Grachev of Russia had agreed to "avoid the further use of force", Russian forces entered the republic in order to "establish constitutional order in Chechnya and to preserve the territorial integrity of Russia." Grachev boasted he could topple Dudayev in a couple of hours with a single airborne regiment, and proclaimed that it will be "a bloodless blitzkrieg, that would not last any longer than 20 December."

Initial stages of conflict

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Initial conflict

On 11 December 1994, Russian forces launched a three-pronged ground attack towards Grozny. The main attack was temporarily halted by the deputy commander of the Russian Ground Forces, General Eduard Vorobyov [ru], who then resigned in protest, stating that it is "a crime" to "send the army against its own people." Many in the Russian military and government opposed the war as well. Yeltsin's adviser on nationality affairs, Emil Pain [ru], and Russia's Deputy Minister of Defense General Boris Gromov (commander of the Afghan War), also resigned in protest of the invasion ("It will be a bloodbath, another Afghanistan", Gromov said on television), as did General Boris Poliakov. More than 800 professional soldiers and officers refused to take part in the operation; of these, 83 were convicted by military courts and the rest were discharged. Later General Lev Rokhlin also refused to be decorated as a Hero of the Russian Federation for his part in the war.

The advance of the northern column was halted by the unexpected Chechen resistance at Dolinskoye and the Russian forces suffered their first serious losses. Units of Chechen fighters inflicted severe losses on the Russian troops. Deeper in Chechnya, a group of 50 Russian paratroopers was captured by the local Chechen militia, after being deployed by helicopters behind enemy lines to capture a Chechen weapons cache. On 29 December, in a rare instance of a Russian outright victory, the Russian airborne forces seized the military airfield next to Grozny and repelled a Chechen counter-attack in the Battle of Khankala; the next objective was the city itself. With the Russians closing in on the capital, the Chechens began to set up defensive fighting positions and grouped their forces in the city.

Storming of Grozny

Main article: Battle of Grozny (1994–95)

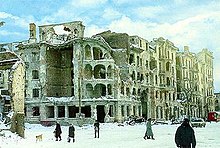

When the Russians besieged the Chechen capital, thousands of civilians died from a week-long series of air raids and artillery bombardments in the heaviest bombing campaign in Europe since the destruction of Dresden. The initial assault on New Year's Eve 1994 ended in a big Russian defeat, resulting in many casualties and at first a nearly complete breakdown of morale in the Russian forces. The fighting claimed the lives of an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 Russian soldiers, mostly barely trained conscripts; the worst losses were inflicted on the 131st 'Maikop' Motor Rifle Brigade, which was destroyed in the fighting near the central railway station. Despite the early Chechen defeat of the New Year's assault and the many further casualties that the Russians had suffered, Grozny was eventually conquered by Russian forces after an urban warfare campaign. After armored assaults failed, the Russian military set out to take the city using air power and artillery. At the same time, the Russian military accused the Chechen fighters of using civilians as human shields by preventing them from leaving the capital as it was bombarded. On 7 January 1995, the Russian Major-General Viktor Vorobyov was killed by mortar fire, becoming the first on a long list of Russian generals to be killed in Chechnya. On 19 January, despite many casualties, Russian forces seized the ruins of the Chechen presidential palace, which had been fought over for more than three weeks as the Chechens abandoned their positions in the ruins of the downtown area. The battle for the southern part of the city continued until the official end on 6 March 1995.

By the estimates of Yeltsin's human rights adviser Sergei Kovalev, about 27,000 civilians died in the first five weeks of fighting. The Russian historian and general Dmitri Volkogonov said the Russian military's bombardment of Grozny killed around 35,000 civilians, including 5,000 children and that the vast majority of those killed were ethnic Russians. While military casualties are not known, the Russian side admitted to having 2,000 soldiers killed or missing. The bloodbath of Grozny shocked Russia and the outside world, inciting severe criticism of the war. International monitors from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) described the scenes as nothing short of an "unimaginable catastrophe", while former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev called the war a "disgraceful, bloody adventure" and German chancellor Helmut Kohl called it "sheer madness".

Continued Russian offensive

Following the fall of Grozny, the Russian government slowly and methodically expanded its control over the lowland areas and then into the mountains. In what was dubbed the worst massacre in the war, the OMON and other federal forces killed up to 300 civilians while seizing the border village of Samashki on 7 April (several hundred more were detained and beaten or otherwise tortured). In the southern mountains, the Russians launched an offensive along all the front on 15 April, advancing in large columns of 200–300 vehicles. The ChRI forces defended the city of Argun, moving their military headquarters first to surrounded Shali, then shortly after to the village of Serzhen'-Yurt as they were forced into the mountains and finally to Shamil Basayev's ancestral stronghold of Vedeno. Chechnya's second-largest city of Gudermes was surrendered without a fight but the village of Shatoy was fought for and defended by the men of Ruslan Gelayev. Eventually, the Chechen command withdrew from the area of Vedeno to the Chechen opposition-aligned village of Dargo and from there to Benoy. According to an estimate cited in a United States Army analysis report, between January and May 1995, when the Russian forces conquered most of the republic in the conventional campaign, their losses in Chechnya were approximately 2,800 killed, 10,000 wounded and more than 500 missing or captured. Some Chechen fighters infiltrated occupied areas, hiding in crowds of returning refugees.

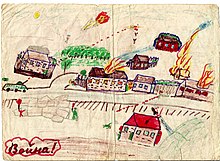

As the war continued, the Chechens resorted to mass hostage-takings, attempting to influence the Russian public and leadership. In June 1995, a group led by the maverick field commander Shamil Basayev took more than 1,500 people hostage in southern Russia in the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis; about 120 Russian civilians died before a ceasefire was signed after negotiations between Basayev and the Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin. The raid forced a temporary stop in Russian military operations, giving the Chechens time to regroup and to prepare for the national militant campaign. The full-scale Russian attack led many of Dzhokhar Dudayev's opponents to side with his forces and thousands of volunteers to swell the ranks of mobile militant units. Many others formed local self-defence militia units to defend their settlements in the case of federal offensive action, officially numbering 5,000–6,000 armed men in late 1995. According to a UN report, the Chechen Armed Forces included a large number of child soldiers, some as young as 11 years old, and also included females. As the territory controlled by them shrank, the Chechens increasingly resorted to classic guerrilla warfare tactics, such as booby traps and mining roads in enemy-held territory. The use of improvised explosive devices was particularly noteworthy; they also exploited a combination of mines and ambushes.

On 6 October 1995, Gen. Anatoliy Romanov, the federal commander in Chechnya at the time, was critically injured and paralyzed in a bomb blast in Grozny. Suspicion of responsibility for the attack fell on rogue elements of the Russian military, as the attack destroyed hopes for a permanent ceasefire based on the developing trust between Gen. Romanov and the ChRI Chief of Staff Aslan Maskhadov, a former colonel in the Soviet Army; in August, the two went to southern Chechnya to try to convince the local commanders to release Russian prisoners. In February 1996, federal and pro-Russian Chechen forces in Grozny opened fire on a massive pro-independence peace march of tens of thousands of people, killing a number of demonstrators. The ruins of the presidential palace, the symbol of Chechen independence, were then demolished two days later.

Continuation of the conflict and mounting Russian defeats

Growing Russian defeats and unpopularity in Russia

On 6 March 1996, a group of Chechen fighters infiltrated Grozny and launched a three-day surprise raid on the city, taking most of it and capturing caches of weapons and ammunition. During the battle, much of the Russian troops were wiped out, with most of them surrendering or routing. After two columns of Russian reinforcements were destroyed on the roads leading to the city, Russian troops eventually gave up on trying to reach the trapped soldiers in the city. Chechen fighters subsequently withdrew from the city on orders from the high command. In the same month in March, Chechen fighters and Russian federal troops clashed near the village of Samashki. The losses on the Russian side amounted to 28 killed and 116 wounded.

On April 16, a month after the initial conflict, Chechen fighters successfully carried out an ambush near Shatoy, wiping out an entire Russian armored column resulting in losses up to 220 soldiers killed in action. In another attack near Vedeno, at least 28 Russian soldiers were killed in action.

As military defeats and growing casualties made the war more and more unpopular in Russia, and as the 1996 presidential elections neared, Boris Yeltsin's government sought a way out of the conflict. Although a Russian guided missile attack assassinated the Chechen president Dzhokhar Dudayev on 21 April 1996. Yeltsin even officially declared "victory" in Grozny on 28 May 1996, after a new temporary ceasefire was signed with the Chechen acting president Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev. While the political leaders were discussing the ceasefire and peace negotiations, Russian forces continued to conduct combat operations. On 6 August 1996, three days before Yeltsin was to be inaugurated for his second term as Russian president and when most of the Russian troops were moved south due to what was planned as their final offensive against remaining mountainous Chechen strongholds, the Chechens subsequently launched another surprise attack on Grozny.

Third Battle of Grozny and the Khasavyurt Accord

Main article: Battle of Grozny (August 1996)Despite Russian troops in and around Grozny numbering approximately 12,000, more than 1,500 Chechen guerrillas (whose numbers soon swelled) overran the key districts within hours in an operation prepared and led by Aslan Maskhadov (who named it Operation Zero) and Shamil Basayev (who called it Operation Jihad). The fighters then laid siege to the Russian posts and bases and the government compound in the city centre, while a number of Chechens deemed to be Russian collaborators were rounded up, detained and, in some cases, executed. At the same time, Russian troops in the cities of Argun and Gudermes were also surrounded in their garrisons. Several attempts by the armored columns to rescue the units trapped in Grozny were repelled with heavy Russian casualties (the 276th Motorized Regiment of 900 men suffered 50% casualties in a two-day attempt to reach the city centre). Russian military officials said that more than 200 soldiers had been killed and nearly 800 wounded in five days of fighting, and that an unknown number were missing; Chechens put the number of Russian dead at close to 1,000. Thousands of troops were either taken prisoner or surrounded and largely disarmed, their heavy weapons and ammunition commandeered by Chechen fighters.

On 19 August, despite the presence of 50,000 to 200,000 Chechen civilians and thousands of federal servicemen in Grozny, the Russian commander Konstantin Pulikovsky gave an ultimatum for Chechen fighters to leave the city within 48 hours, or else it would be leveled in a massive aerial and artillery bombardment. He stated that federal forces would use strategic bombers (not used in Chechnya up to this point) and ballistic missiles. This announcement was followed by chaotic scenes of panic as civilians tried to flee before the army carried out its threat, with parts of the city ablaze and falling shells scattering refugee columns. The bombardment was however soon halted by the ceasefire brokered by General Alexander Lebed, Yeltsin's national security adviser, on 22 August. Gen. Lebed called the ultimatum, issued by General Pulikovsky (replaced by then), a "bad joke".

During eight hours of subsequent talks, Lebed and Maskhadov drafted and signed the Khasavyurt Accord on 31 August 1996. It included: technical aspects of demilitarization, the withdrawal of both sides' forces from Grozny, the creation of joint headquarters to preclude looting in the city, the withdrawal of all federal forces from Chechnya by 31 December 1996, and a stipulation that any agreement on the relations between the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and the Russian federal government need not be signed until late 2001.

Human rights violations and war crimes

Human rights organizations accused Russian forces of engaging in indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force whenever they encountered resistance, resulting in numerous civilian deaths. (According to Human Rights Watch, Russian artillery and rocket attacks killed at least 267 civilians during the December 1995 raid by the Chechens on the city of Gudermes.) Throughout the span of the first Chechen war, Russian forces have been accused by human rights organizations of starting a brutal war with total disregard for humanitarian law, causing tens of thousands of unnecessary civilian casualties among the Chechen population. The main strategy in the Russian war effort had been to use heavy artillery and air strikes leading to numerous indiscriminate attacks on civilians. This has led to Western and Chechen sources calling the Russian strategy deliberate terror bombing on parts of Russia. According to Human Rights Watch, the campaign was "unparalleled in the area since World War II for its scope and destructiveness, followed by months of indiscriminate and targeted fire against civilians". Due to ethnic Chechens in Grozny seeking refuge among their respective teips in the surrounding villages of the countryside, a high proportion of initial civilian casualties were inflicted against ethnic Russians who were unable to find viable escape routes. The villages were also attacked from the first weeks of the conflict (Russian cluster bombs, for example, killed at least 55 civilians during the 3 January 1995 Shali cluster bomb attack).

Russian soldiers often prevented civilians from evacuating areas of imminent danger and prevented humanitarian organizations from assisting civilians in need. It was widely alleged that Russian troops, especially those belonging to the Internal Troops (MVD), committed numerous and in part systematic acts of torture and summary executions on Chechen civilians; they were often linked to zachistka ("cleansing" raids on town districts and villages suspected of harboring boyeviki – militants). Humanitarian and aid groups chronicled persistent patterns of Russian soldiers killing, raping and looting civilians at random, often in disregard of their nationality. Chechen fighters took hostages on a massive scale, kidnapped or killed Chechens considered to be collaborators and mistreated civilian captives and federal prisoners of war (especially pilots). Russian federal forces kidnapped hostages for ransom and used human shields for cover during the fighting and movement of troops (for example, a group of surrounded Russian troops took approximately 500 civilian hostages at Grozny's 9th Municipal Hospital).

The violations committed by members of the Russian forces were usually tolerated by their superiors and were not punished even when investigated (the story of Vladimir Glebov serving as an example of such policy). Television and newspaper accounts widely reported largely uncensored images of the carnage to the Russian public. The Russian media coverage partially precipitated a loss of public confidence in the government and a steep decline in President Yeltsin's popularity. Chechnya was one of the heaviest burdens on Yeltsin's 1996 presidential election campaign. The protracted war in Chechnya, especially many reports of extreme violence against civilians, ignited fear and contempt of Russia among other ethnic groups in the federation. One of the most notable war crimes committed by the Russian army is the Samashki massacre, in which it is estimated that up to 300 civilians died during the attack. Russian forces conducted an operation of zachistka, house-by-house searches throughout the entire village. Federal soldiers deliberately and arbitrarily attacked civilians and civilian dwellings in Samashki by shooting residents and burning houses with flame-throwers. They wantonly opened fire or threw grenades into basements where residents, mostly women, elderly persons and children, had been hiding. Russian troops intentionally burned many bodies, either by throwing the bodies into burning houses or by setting them on fire. A Chechen surgeon, Khassan Baiev, treated wounded in Samashki immediately after the operation and described the scene in his book:

Dozens of charred corpses of women and children lay in the courtyard of the mosque, which had been destroyed. The first thing my eye fell on was the burned body of a baby, lying in fetal position... A wild-eyed woman emerged from a burned-out house holding a dead baby. Trucks with bodies piled in the back rolled through the streets on the way to the cemetery.

While treating the wounded, I heard stories of young men – gagged and trussed up – dragged with chains behind personnel carriers. I heard of Russian aviators who threw Chechen prisoners, screaming, out their helicopters. There were rapes, but it was hard to know how many because women were too ashamed to report them. One girl was raped in front of her father. I heard of one case in which the mercenary grabbed a newborn baby, threw it among each other like a ball, then shot it dead in the air.

Leaving the village for the hospital in Grozny, I passed a Russian armored personnel carrier with the word SAMASHKI written on its side in bold, black letters. I looked in my rearview mirror and to my horror saw a human skull mounted on the front of the vehicle. The bones were white; someone must have boiled the skull to remove the flesh.

Major Vyacheslav Izmailov is said to have rescued at least 174 people from captivity on both sides in the war, was later involved in the tracing of missing persons after the war and in 2021 won the hero's prize at the Stalker Human Rights Film Festival in Moscow.

Spread of the war

The declaration by Chechnya's Chief Mufti Akhmad Kadyrov that the ChRI was waging a Jihad (struggle) against Russia raised the spectre that Jihadis from other regions and even outside Russia would enter the war.

Limited fighting occurred in the neighbouring a small republic of Ingushetia, mostly when Russian commanders sent troops over the border in pursuit of Chechen fighters, while as many as 200,000 refugees (from Chechnya and the conflict in North Ossetia) strained Ingushetia's already weak economy. On several occasions, Ingush president Ruslan Aushev protested incursions by Russian soldiers and even threatened to sue the Russian Ministry of Defence for damages inflicted, recalling how the federal forces previously assisted in the expulsion of the Ingush population from North Ossetia. Undisciplined Russian soldiers were also reported to be committing murders, rapes, and looting in Ingushetia (in an incident partially witnessed by visiting Russian Duma deputies, at least nine Ingush civilians and an ethnic Bashkir soldier were murdered by apparently drunk Russian soldiers; earlier, drunken Russian soldiers killed another Russian soldier, five Ingush villagers and even Ingushetia's Health Minister).

Much larger and more deadly acts of hostility took place in the Republic of Dagestan. In particular, the border village of Pervomayskoye was completely destroyed by Russian forces in January 1996 in reaction to the large-scale Chechen hostage taking in Kizlyar in Dagestan (in which more than 2,000 hostages were taken), bringing strong criticism from this hitherto loyal republic and escalating domestic dissatisfaction. The Don Cossacks of Southern Russia, originally sympathetic to the Chechen cause, turned hostile as a result of their Russian-esque culture and language, stronger affinity to Moscow than to Grozny, and a history of conflict with indigenous peoples such as the Chechens. The Kuban Cossacks started organizing themselves against the Chechens, including manning paramilitary roadblocks against infiltration of their territories.

Meanwhile, the war in Chechnya spawned new forms of resistance to the federal government. Opposition to the conscription of men from minority ethnic groups to fight in Chechnya was widespread among other republics, many of which passed laws and decrees on the subject. For example, the government of Chuvashia passed a decree providing legal protection to soldiers from the republic who refused to participate in the Chechen war and imposed limits on the use of the federal army in ethnic or regional conflicts within Russia. Tatarstan president Mintimer Shaimiev vocally opposed the war and appealed to Yeltsin to stop it and return conscripts, warning the conflict was at risk of expanding across the Caucasus. Some regional and local legislative bodies called for the prohibition on the use of draftees in quelling internal conflicts, while others demanded a total ban on the use of the armed forces in such situations. Russian government officials feared that a move to end the war short of victory would create a cascade of secession attempts by other ethnic minorities.

On 16 January 1996, a Turkish passenger ship carrying 200 Russian passengers was taken over by what were mostly Turkish gunmen who were seeking to publicize the Chechen cause. On 6 March, a Cypriot passenger jet was hijacked by Chechen sympathisers while flying toward Germany. Both of these incidents were resolved through negotiations, and the hijackers surrendered without any fatalities being inflicted.

Aftermath

Casualties

According to the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, 3,826 troops were killed, 17,892 troops were wounded, and 1,906 troops are missing in action. According to the NVO, the authoritative Russian independent military weekly, at least 5,362 Russian soldiers died during the war, 52,000 Russian soldiers were wounded or became diseased and some 3,000 more Russian soldiers were still missing in 2005. However, the Committee of Soldiers' Mothers of Russia estimated that the total number of Russian military deaths was 14,000, based on information which it collected from wounded troops and soldiers' relatives (only counting regular troops, i.e. not the kontraktniki (contract soldiers, not conscripts) and members of the special service forces). The list which contains the names of the dead soldiers, drawn up by the Human Rights Center "Memorial", contains 4,393 names. In 2009, the official number of Russian troops who fought in the two wars and were still missing in Chechnya and presumed dead was some 700, while about 400 remains of the missing servicemen were said to have been recovered up to that point. The Russian military was notorious for hiding casualties.

Let me tell you about one specific case. I knew for sure that on this day – it was the end of February or the beginning of March 1995 – forty servicemen of the Joint Group were killed. And they bring me information about fifteen. I ask: "Why don't you take into account the rest?" They hesitated: "Well, you see, 40 is a lot. We'd better spread those losses over a few days." Of course, I was outraged by these manipulations.

— Anatoly Kulikov

The Chechen formations also suffered fairly high losses. According to the militants, they lost 3,000 fighters. According to official Russian data, Chechen militants lost 17,391 people killed.

According to the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University,

Estimates of the number of civilians killed range widely from 20,000 to 100,000, with the latter figure commonly referenced by Chechen sources. Most scholars and human rights organizations generally estimate the number of civilian casualties to be 40,000; this figure is attributed to the research and scholarship of Chechnya expert John Dunlop, who estimates that the total number of civilian casualties is at least 35,000. This range is also consistent with post-war publications by the Russian statistics office estimating 30,000 to 40,000 civilians killed. The Moscow-based human rights organization, Memorial, which actively documented human rights abuses throughout the war, estimates the number of civilian casualties to be a slightly higher at 50,000.

Russian Interior Minister Anatoly Kulikov claimed that fewer than 20,000 civilians were killed. Médecins Sans Frontières estimated a death toll of 50,000 people out of a population of 1,000,000. Sergey Kovalyov's team could offer their conservative, documented estimate of more than 50,000 civilian deaths. Alexander Lebed asserted that 80,000 to 100,000 had been killed and 240,000 had been injured. The number given by the ChRI authorities was about 100,000 killed.

According to claims made by Sergey Govorukhin which were published in the Russian newspaper Gazeta, approximately 35,000 ethnic Russian civilians were killed by Russian forces which operated in Chechnya, most of them were killed during the bombardment of Grozny.

According to various estimates, the number of Chechens who are dead or missing is between 50,000 and 100,000.

Prisoners and missing persons

In the Khasavyurt Accord, both sides agreed to an "all for all" exchange of prisoners to be carried out at the end of the war. However, despite this commitment, many persons remained forcibly detained. A partial analysis of the list of 1,432 reported missing found that, as of 30 October 1996, at least 139 Chechens were still being forcibly detained by the Russian side; it was entirely unclear how many of these men were alive. As of mid-January 1997, the Chechens still held between 700 and 1,000 Russian soldiers and officers as prisoners of war, according to Human Rights Watch. According to Amnesty International that same month, 1,058 Russian soldiers and officers were being detained by Chechen fighters who were willing to release them in exchange for members of Chechen armed groups. American freelance journalist Andrew Shumack has been missing from the Chechen capital, Grozny since July 1995 and is presumed dead.

Major Vyacheslav Izmailov, who had rescued at least 174 people from captivity on both sides in the war, was later involved in the search for missing persons. He was honoured as the human rights hero in the Stalker Human Rights Film Festival after he featured in Anna Artemyeva's film Don't Shoot at the Bald Man!, which won the jury prize for Best Documentary at the festival in Moscow. He later worked as military correspondent for Novaya Gazeta, was part of the team of journalists investigating the murder of journalist Anna Politkovskaya in 2006 He also helped families to find their sons who had gone missing in the Chechen war.

Moscow peace treaty

The Khasavyurt Accord paved the way for the signing of two further agreements between Russia and Chechnya. In mid-November 1996, Yeltsin and Maskhadov signed an agreement on economic relations and reparations to Chechens who had been affected by the 1994–96 war. In February 1997, Russia also approved an amnesty for Russian soldiers and Chechen fighters alike who committed illegal acts in connection with the War in Chechnya between December 1994 and September 1996.

Six months after the Khasavyurt Accord, on 12 May 1997, Chechen-elected president Aslan Maskhadov traveled to Moscow where he and Yeltsin signed a formal treaty "on peace and the principles of Russian-Chechen relations" that Maskhadov predicted would demolish "any basis to create ill-feelings between Moscow and Grozny." Maskhadov's optimism, however, proved misplaced. Little more than two years later, some of Maskhadov's former comrades-in-arms, led by field commanders Shamil Basayev and Ibn al-Khattab, launched an invasion of Dagestan in the summer of 1999 – and soon Russia's forces entered Chechnya again, marking the beginning of the Second Chechen War.

Foreign policy implications

Further information: Reactions to the First Chechen WarFrom the outset of the First Chechen conflict, Russian authorities struggled to reconcile new international expectations with widespread accusations of Soviet-style heaviness in their execution of the war. For example, Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev, who was generally regarded as a Western-leaning liberal, made the following remark when questioned about Russia's conduct during the war; "'Generally speaking, it is not only our right but our duty not to allow uncontrolled armed formations on our territory. The Foreign Ministry stands on guard over the country's territorial unity. International law says that a country not only can but must use force in such instances ... I say it was the right thing to do ... The way in which it was done is not my business." These attitudes contributed greatly to the growing doubts in the West as to whether Russia was sincere in its stated intentions to implement democratic reforms. The general disdain for Russian behavior in the Western political establishment contrasted heavily with widespread support in the Russian public. Domestic political authorities' arguments emphasizing stability and the restoration of order resonated with the public and quickly became an issue of state identity.

On 18 October 2022, Ukraine's parliament condemned the "genocide of the Chechen people" during the First and Second Chechen War.

See also

- 1940–1944 insurgency in Chechnya

- Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush

- History of Chechnya

- History of Russia (1991–present)

- Islam in Russia

- Military history of the Russian Federation

- Second Chechen War – 1999–2009 conflict in Chechnya and the North Caucasus

- Circassian genocide

- List of wars involving Russia

Notes

- Author says the figure could reach as high as 10,000.

- According to Movladi Udugov, the press secretary of Dzhokhar Dudayev in an interview in January 1995

- 120 in Budyonnovsk, and 41 in Pervomayskoe hostage crisis

References

- "TURKISH VOLUNTEERS IN CHECHNYA". Jamestown. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-02-14.

- Amjad M. Jaimoukha (2005). The Chechens: A Handbook. Psychology Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- Politics of Conflict: A Survey, p. 68, at Google Books

- Energy and Security in the Caucasus, p. 66, at Google Books

- "Radical Ukrainian Nationalism and the War in Chechnya". Jamestown. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2019-04-12. -UNSO's "Argo" squad -Viking Brigade

- Cooley, John K. (2002). Unholy Wars: Afghanistan, America and International Terrorism (3rd ed.). London: Pluto Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-7453-1917-9.

A Turkish Fascist youth group, the "Grey Wolves," was recruited to fight with the Chechens.

- Goltz, Thomas (2003). Chechnya Diary: A War Correspondent's Story of Surviving the War in Chechnya. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-312-26874-9.

I called a well-informed diplomat pal and arranged to meet him at a bar favored by the pan-Turkic crowd known as the Gray Wolves, who were said to be actively supporting the Chechens with men and arms.

...the Azerbaijani Gray Wolf leader, Iskander, Hamidov... - Isingor, Ali (6 September 2000). "Istanbul: Gateway to a holy war". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014.

- "Grey Wolves in Syria". Egypt Today. 11 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Galeotti, Mark (2014). Russia's War in Chechnya 1994–2009. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-279-6.

- "Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy" (PDF). World Bank Document. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- Lutz, Raymond R. (April 1997). "Russian Strategy In Chechnya: a Case Study in Failure". Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Radical Ukrainian Nationalism and the War in Chechnya". Jamestown. The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2019-04-12.

- Кривошеев, Г. Ф., ed. (2001). Россия и СССР в войнах XX века. Потери вооруженных сил (in Russian). Олма-Пресс. p. 581. ISBN 5-224-01515-4.

- Кривошеев, Г. Ф., ed. (2001). Россия и СССР в войнах XX века. Потери вооруженных сил (in Russian). Олма-Пресс. p. 582. ISBN 5-224-01515-4.

- Кривошеев, Г. Ф., ed. (2001). Россия и СССР в войнах XX века. Потери вооруженных сил (in Russian). Олма-Пресс. p. 584. ISBN 5-224-01515-4.

- ^ "Война, проигранная по собственному желанию". Archived from the original on 2023-02-13. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- "Первая чеченская война – 20 лет назад". 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "The War in Chechnya". MN-Files. Mosnews.com. 2007-02-07. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008.

- ^ Saradzhyan, Simon (2005-03-09). "Army Learned Few Lessons From Chechnya". Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- Andrei, Sakharov (4 November 1999). "The Second Chechen War". Reliefweb. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- Gordon, Michael R. (4 September 1996). "Human Rights Violations in Chechnya". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2002-12-28. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- Felgenhauer, Pavel. "The Russian Army in Chechnya". Crimes of War. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Cherkasov, Alexander. "Book of Numbers, Book of Losses, Book of the Final Judgment". Polit.ru. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ Casualty Figures Jamestown Foundation Archived August 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "The War That Continues to Shape Russia, 25 Years Later". The New York Times. 2019-12-10. Archived from the original on 2019-12-10. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- Aurélie, Campana (2007-11-05). "The Massive Deportation of the Chechen People: How and why Chechens were Deported". Sciences Po. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- "Explore Chechnya's Turbulent Past ~ 1944: Deportation | Wide Angle | PBS". PBS. 25 July 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- Evangelista, Matthew (2002). The Chechen Wars: Will Russia Go the Way of the Soviet Union?. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8157-2498-8.

- German, Tracey C. (2003). Russia's Chechen War. New York: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-415-29720-2.

- Gall, Carlotta; De Waal, Thomas (1998). Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus. New York: New York University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8147-2963-2.

Vitaly Kutsenko, the elderly First Secretary of the town soviet either was defenestrated or tried to clamber out to escape the crowd.

- "Первая война" [First war]. kommersant.ru (in Russian). 13 December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

... По данным Центризбиркома Чечено-Ингушетии, в выборах принимают участие 72% избирателей, за генерала Дудаева голосуют 412,6 тыс. человек (90,1%) ...'

- Kempton, Daniel R., ed. (2002). Unity Or Separation Center-periphery Relations in the Former Soviet Union. Praeger. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-275-97011-6.

- Tishkov, Valery (2004). Chechnya Life in a War-Torn Society. University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-520-23888-6.

- ^ Allah's Mountains: Politics and War in the Russian Caucasus By Sebastian Smith p. 134

- Moscow News. November 22–29, 1992

- Moscow News. September 1–7, 1995

- Efim Sandler, Battle for Grozny, Volume 1: Prelude and the Way to the City: First Chechen War 1994 (Helion Europe @ War No. 31), Warwick, 2023, pp.34-40.

- The battle(s) of Grozny Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Cherkasov, Alexander; Golubev, Ostav; Malykhin, Vladimir (24 February 2023), "A chain of wars, a chain of crimes, a chain of impunity: Russian wars in Chechnya, Syria and Ukraine" (PDF), Memorial Human Rights Defence Centre, pp. 17–18, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2024, retrieved 28 May 2023

- ^ Gall, Carlotta; Thomas de Waal (1998). Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2963-2.

- Efron, Sonni (January 10, 1995). "Aerial Death Threat Sends Chechens Fleeing From Village: Caucasus: Russians warn they will bomb five towns near Grozny unless 50 captured paratroopers are quickly freed". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Williams, Bryan Glyn (2001).The Russo-Chechen War: A Threat to Stability in the Middle East and Eurasia? Archived 2022-03-16 at the Wayback Machine. Middle East Policy 8.1.

- "BBC News – EUROPE – Chechens 'using human shields'". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2003-03-17. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- Faurby, Ib; Märta-Lisa Magnusson (1999). "The Battle(s) of Grozny". Baltic Defence Review (2): 75–87. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011.

- "The First Bloody Battle". The Chechen Conflict. BBC News. 2000-03-16. Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ The Russian Federation Human Rights Developments Archived 2013-05-25 at the Wayback Machine Human Rights Watch

- "Alikhadzhiev interview" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- "Iskhanov interview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2008.

- "FM 3-06.11 Appendix H". inetres.com. Archived from the original on 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- Timothy L. Thomas; Charles P. O'Hara. "Combat Stress in Chechnya: "The Equal Opportunity Disorder"". Foreign Military Studies Office Publications. Archived from the original on 2007-08-01.

- "The situation of human rights in the Republic of Chechnya of the Russian Federation". United Nations. 26 March 1996. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012.

- Specter, Michael (1995-11-21). "Pro-Russian Chechen Leader Survives Bombing in Capital". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2024-04-22. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- "Honoring a General Who is Silenced". The St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014.

- "Chechnya: Election Date Postponed, Prisoner Exchange in Trouble". Monitor. Vol. 1, no. 69. The Jamestown Foundation. August 8, 1995. Archived from the original on 2006-11-22.

- Chris Hunter. "Mass protests in Grozny end in bloodshed". hartford-hwp.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- Akhmadov, Ilyas; Lanskoy, Miriam (2010). The Chechen Struggle: Independence Won and Lost. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN. p. 64.

- Гродненский, Николай. Неоконченная война: история вооруженного конфликта в Чечне. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- Russian fighting ceases in Chechnya; Skeptical troops comply with Yeltsin order CNN Archived March 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Yeltsin declares Russian victory over Chechnya CNN Archived December 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- History of Chechnya Archived 2012-01-30 at the Wayback Machine WaYNaKH Online

- "czecz". memo.ru. Archived from the original on 2016-12-15. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- Lebed calls off assault on Grozny The Daily Telegraph

- Lebed promises peace in Grozny and no Russian assault CNN Archived December 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Lee Hockstader and David Hoffman (1996-08-22). "Russian Official Vows To Stop Raid". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2012-02-03.

- Blank, Stephen J. "Russia's invasion of Chechnya: a preliminary assessment" (PDF). dtic.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2008.

- "Human Rights Developments". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- "Grozny, August 1996. Occupation of Municipal Hospital No. 9 Memorial". memo.ru. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- "Mothers' March to Grozny". War Resisters' International. 1 June 1995. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- The situation of human rights in the Republic of Chechnya of the Russian Federation – Report of the Secretary-General UNCHR Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- DETAILS OF SAMASHKI MASSACRE EMERGE., The Jamestown Foundation, 5 May 1995 Archived 25 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Baiev, Khassan (2003). The Oath A Surgeon Under Fire. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0-8027-1404-8.

- ^ "The Jury Prize of the Stalker Festival was awarded to a film about Major Izmailov". 247 News Bulletin. 17 December 2021. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Can Russia's Press Ever Be Free?". The New Yorker. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "July archive". jhu.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- "Army demoralized". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- "Mintimer Shaimiev: "Stop the Civil War". The first Chechen war and the reaction of the authorities of Tatarstan". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Russian). 10 November 2022. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- "hrvc.net". Archived from the original on 2002-12-28.

- "Неизвестный солдат кавказской войны". memo.ru. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- "700 Russian servicemen missing in Chechnya – officer". Interfax. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015.

- "So 500 people or 9 thousand? We tell you how many people Russia lost in past wars and what numbers they called". Zerkalo (in Russian). 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- Кривошеев, Г. Ф., ed. (2001). Россия и СССР в войнах XX века. Потери вооруженных сил (in Russian). Олма-Пресс. p. 584. ISBN 5-224-01515-4.

- "Russia: Chechen war – Mass Atrocity Endings". sites.tufts.edu. 2015-08-07. Archived from the original on 2020-09-08. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ "Civil and military casualties of the wars in Chechnya". Archived from the original on December 28, 2002. Retrieved June 1, 2016. Russian-Chechen Friendship Society

- Binet, Laurence (2014). War crimes and politics of terror in Chechnya 1994–2004 (PDF). Médecins Sans Frontières. p. 83. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-06. Retrieved 2019-01-02.

- Dunlop, John B. (January 26, 2005). "Do Ethnic Russians Support Putin's War in Chechnya?". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on March 3, 2008.

- ^ "RUSSIA / CHECHNYA". hrw.org. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- AI Report 1998: Russian Federation Amnesty International Archived November 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Journalists Missing 1982–2009". Refworld. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- "Vyacheslav Izmailov: we know who ordered Anna Politkovskaya's murder". North Caucasus Weekly. 8 (22). 31 May 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2022 – via The Jamestown Foundation.

- "Account Suspended". worldaffairsboard.com. 7 May 2004. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- "F&P RFE/RL Archive". friends-partners.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- Hanna, Smith (2014). "Russian Greatpowerness: Foreign policy, the Two Chechen Wars and International Organisations". University of Helsinki.

- Horga, Ioana. "Cfsp into the Spotlight: The European Union's Foreign Policy toward Russia during the Chechen Wars". Annals of University of Oradea, Series: International Relations & European Studies.

- "Ukraine's parliament declares the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria 'temporarily occupied by Russia' and condemns 'genocide of Chechens'". Novaya Gazeta. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Ukraine's parliament declares 'Chechen Republic of Ichkeria' Russian-occupied territory". Meduza. 18 October 2022. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

Further reading

- Bennett, Vanora (1998). Crying Wolf: The Return of War to Chechnya. London: Picador. ISBN 978-0-330-35170-6.

- Goltz, Thomas (2003). Chechnya Diary: A War Correspondent's Story of Surviving the War in Chechnya. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-26874-9.

- Stone, David R. (2006). A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the War in Chechnya. Westport: Praeger Security International. ISBN 978-0-275-98502-8.

- Politkovskaya, Anna (2003). A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-67432-2.

- Smith, Sebastian (2006). Allah's Mountains: The Battle for Chechnya. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1-85043-979-0.

- Seierstad, Åsne (2008). The Angel of Grozny: Inside Chechnya. London: Virago Press. ISBN 978-1-84408-516-3.

- Gall, Carlotta; de Waal, Thomas (1998). Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2963-2.

- Hughes, James (2007). Chechnya: From Nationalism to Jihad. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4013-9.

- Wood, Tony (2007). Chechnya: The Case for Independence. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-114-4.

- Lieven, Anatol (1998). Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian Power. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07398-0.

- Nikitina, Elena; Quinlan, Patrick (2017). Girl, Taken: A True Story of Abduction, Captivity and Survival. London: Iliad Books. ISBN 978-0-9882138-6-9.

- Goytisolo, Juan (2000). Landscapes of War: From Sarajevo to Chechnya. Translated by Bush, Peter. Introduction by Tariq Ali. San Francisco: City Lights Books. ISBN 978-0-87286-373-6.

- Collins, Aukai (2002). My Jihad: The True Story of an American Mujahid's Amazing Journey from Usama Bin Laden's Training Camps to Counterterrorism with the FBI and CIA. Guilford: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-565-4.

- Greene, Stanley (2003). Open Wound: Chechnya 1994 to 2003. London: Trolley Books. ISBN 978-1-904563-01-3.

- Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63184-6.

- Cassidy, Robert M. (2003). Russia in Afghanistan and Chechnya: Military Strategic Culture and the Paradoxes of Asymmetric Conflict. Carlisle: U.S. Army War College. ISBN 978-1-58487-110-1.

- German, Tracey C. (2003). Russia's Chechen War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29720-2.

- Galeotti, Mark (2014). Russia's Wars in Chechnya 1994–2009. Essential Histories. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-277-2.

- Aldis, Anne C.; McDermott, Roger N., eds. (2003). Russian Military Reform, 1992-2002. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5475-1.

- Evangelista, Matthew (2002). The Chechen Wars: Will Russia Go the Way of the Soviet Union?. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-2498-8.

- Grammer, Moshe (2006). The Lone Wolf and the Bear: Three Centuries of Chechen Defiance of Russian Rule. London: Hurst Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-743-9.

- Baev, Pavel K. (1996). The Russian Army: In a Time of Troubles. London: SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-5187-2.

- Baiev, Khassan; Daniloff, Nicholas; Daniloff, Ruth (2003). The Oath: A Surgeon Under Fire. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0-679-31156-0.

External links

- Chechen War 1994–96 The World Regional Conflicts Project

- Chechnya Crimes of War Project

- Chechnya Reference Library A collection of analyses and interviews of Chechen commanders conducted by the United States Marine Corps

- Damned and forgotten Documentary by Sergey Govorukhin

- The Chechen Campaign by Pavel Felgenhauer

- War and Human Rights Memorial human rights group

- Why It All Went So Very Wrong Time

- Why the Russian Military Failed in Chechnya U.S. Foreign Studies

| Armed conflicts involving Russia (including Tsarist, Imperial and Soviet times) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related |

| ||||

| Internal | |||||

| Tsardom of Russia |

| ||||

| 18th–19th century |

| ||||

| 20th century |

| ||||

| 21st century | |||||

| Boris Yeltsin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Life and politics | |

| Presidency |

|

| Elections | |

| Commemoration |

|

| Books | |

| Films | |

| Family |

|