In physics, total internal reflection (TIR) is the phenomenon in which waves arriving at the interface (boundary) from one medium to another (e.g., from water to air) are not refracted into the second ("external") medium, but completely reflected back into the first ("internal") medium. It occurs when the second medium has a higher wave speed (i.e., lower refractive index) than the first, and the waves are incident at a sufficiently oblique angle on the interface. For example, the water-to-air surface in a typical fish tank, when viewed obliquely from below, reflects the underwater scene like a mirror with no loss of brightness (Fig. 1).

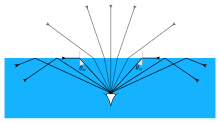

TIR occurs not only with electromagnetic waves such as light and microwaves, but also with other types of waves, including sound and water waves. If the waves are capable of forming a narrow beam (Fig. 2), the reflection tends to be described in terms of "rays" rather than waves; in a medium whose properties are independent of direction, such as air, water or glass, the "rays" are perpendicular to associated wavefronts. The total internal reflection occurs when critical angle is exceeded.

Refraction is generally accompanied by partial reflection. When waves are refracted from a medium of lower propagation speed (higher refractive index) to a medium of higher propagation speed (lower refractive index)—e.g., from water to air—the angle of refraction (between the outgoing ray and the surface normal) is greater than the angle of incidence (between the incoming ray and the normal). As the angle of incidence approaches a certain threshold, called the critical angle, the angle of refraction approaches 90°, at which the refracted ray becomes parallel to the boundary surface. As the angle of incidence increases beyond the critical angle, the conditions of refraction can no longer be satisfied, so there is no refracted ray, and the partial reflection becomes total. For visible light, the critical angle is about 49° for incidence from water to air, and about 42° for incidence from common glass to air.

Details of the mechanism of TIR give rise to more subtle phenomena. While total reflection, by definition, involves no continuing flow of power across the interface between the two media, the external medium carries a so-called evanescent wave, which travels along the interface with an amplitude that falls off exponentially with distance from the interface. The "total" reflection is indeed total if the external medium is lossless (perfectly transparent), continuous, and of infinite extent, but can be conspicuously less than total if the evanescent wave is absorbed by a lossy external medium ("attenuated total reflectance"), or diverted by the outer boundary of the external medium or by objects embedded in that medium ("frustrated" TIR). Unlike partial reflection between transparent media, total internal reflection is accompanied by a non-trivial phase shift (not just zero or 180°) for each component of polarization (perpendicular or parallel to the plane of incidence), and the shifts vary with the angle of incidence. The explanation of this effect by Augustin-Jean Fresnel, in 1823, added to the evidence in favor of the wave theory of light.

The phase shifts are used by Fresnel's invention, the Fresnel rhomb, to modify polarization. The efficiency of the total internal reflection is exploited by optical fibers (used in telecommunications cables and in image-forming fiberscopes), and by reflective prisms, such as image-erecting Porro/roof prisms for monoculars and binoculars.

Optical description

Although total internal reflection can occur with any kind of wave that can be said to have oblique incidence, including (e.g.) microwaves and sound waves, it is most familiar in the case of light waves.

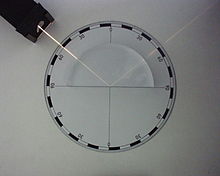

Total internal reflection of light can be demonstrated using a semicircular-cylindrical block of common glass or acrylic glass. In Fig. 3, a "ray box" projects a narrow beam of light (a "ray") radially inward. The semicircular cross-section of the glass allows the incoming ray to remain perpendicular to the curved portion of the air/glass surface, and then hence to continue in a straight line towards the flat part of the surface, although its angle with the flat part varies.

Where the ray meets the flat glass-to-air interface, the angle between the ray and the normal (perpendicular) to the interface is called the angle of incidence. If this angle is sufficiently small, the ray is partly reflected but mostly transmitted, and the transmitted portion is refracted away from the normal, so that the angle of refraction (between the refracted ray and the normal to the interface) is greater than the angle of incidence. For the moment, let us call the angle of incidence θi and the angle of refraction θt (where t is for transmitted, reserving r for reflected). As θi increases and approaches a certain "critical angle", denoted by θc (or sometimes θcr), the angle of refraction approaches 90° (that is, the refracted ray approaches a tangent to the interface), and the refracted ray becomes fainter while the reflected ray becomes brighter. As θi increases beyond θc, the refracted ray disappears and only the reflected ray remains, so that all of the energy of the incident ray is reflected; this is total internal reflection (TIR). In brief:

- If θi < θc, the incident ray is split, being partly reflected and partly refracted;

- If θi > θc, the incident ray suffers total internal reflection (TIR); none of it is transmitted.

Critical angle

The critical angle is the smallest angle of incidence that yields total reflection, or equivalently the largest angle for which a refracted ray exists. For light waves incident from an "internal" medium with a single refractive index n1, to an "external" medium with a single refractive index n2, the critical angle is given by and is defined if n2 ≤ n1. For some other types of waves, it is more convenient to think in terms of propagation velocities rather than refractive indices. The explanation of the critical angle in terms of velocities is more general and will therefore be discussed first.

When a wavefront is refracted from one medium to another, the incident (incoming) and refracted (outgoing) portions of the wavefront meet at a common line on the refracting surface (interface). Let this line, denoted by L, move at velocity u across the surface, where u is measured normal to L (Fig. 4). Let the incident and refracted wavefronts propagate with normal velocities and respectively, and let them make the dihedral angles θ1 and θ2 respectively with the interface. From the geometry, is the component of u in the direction normal to the incident wave, so that Similarly, Solving each equation for 1/u and equating the results, we obtain the general law of refraction for waves:

| 1 |

But the dihedral angle between two planes is also the angle between their normals. So θ1 is the angle between the normal to the incident wavefront and the normal to the interface, while θ2 is the angle between the normal to the refracted wavefront and the normal to the interface; and Eq. (1) tells us that the sines of these angles are in the same ratio as the respective velocities.

This result has the form of "Snell's law", except that we have not yet said that the ratio of velocities is constant, nor identified θ1 and θ2 with the angles of incidence and refraction (called θi and θt above). However, if we now suppose that the properties of the media are isotropic (independent of direction), two further conclusions follow: first, the two velocities, and hence their ratio, are independent of their directions; and second, the wave-normal directions coincide with the ray directions, so that θ1 and θ2 coincide with the angles of incidence and refraction as defined above.

Obviously the angle of refraction cannot exceed 90°. In the limiting case, we put θ2 = 90° and θ1 = θc in Eq. (1), and solve for the critical angle:

| 2 |

In deriving this result, we retain the assumption of isotropic media in order to identify θ1 and θ2 with the angles of incidence and refraction.

For electromagnetic waves, and especially for light, it is customary to express the above results in terms of refractive indices. The refractive index of a medium with normal velocity is defined as where c is the speed of light in vacuum. Hence Similarly, Making these substitutions in Eqs. (1) and (2), we obtain

| 3 |

and

| 4 |

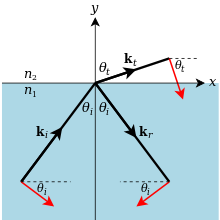

Eq. (3) is the law of refraction for general media, in terms of refractive indices, provided that θ1 and θ2 are taken as the dihedral angles; but if the media are isotropic, then n1 and n2 become independent of direction, while θ1 and θ2 may be taken as the angles of incidence and refraction for the rays, and Eq. (4) follows. So, for isotropic media, Eqs. (3) and (4) together describe the behavior in Fig. 5.

According to Eq. (4), for incidence from water (n1 ≈ 1.333) to air (n2 ≈ 1), we have θc ≈ 48.6°, whereas for incidence from common or acrylic glass (n1 ≈ 1.50) to air (n2 ≈ 1), we have θc ≈ 41.8°.

The arcsin function yielding θc is defined only if n2 ≤ n1 Hence, for isotropic media, total internal reflection cannot occur if the second medium has a higher refractive index (lower normal velocity) than the first. For example, there cannot be TIR for incidence from air to water; rather, the critical angle for incidence from water to air is the angle of refraction at grazing incidence from air to water (Fig. 6).

The medium with the higher refractive index is commonly described as optically denser, and the one with the lower refractive index as optically rarer. Hence it is said that total internal reflection is possible for "dense-to-rare" incidence, but not for "rare-to-dense" incidence.

Everyday examples

When standing beside an aquarium with one's eyes below the water level, one is likely to see fish or submerged objects reflected in the water-air surface (Fig. 1). The brightness of the reflected image – just as bright as the "direct" view – can be startling.

A similar effect can be observed by opening one's eyes while swimming just below the water's surface. If the water is calm, the surface outside the critical angle (measured from the vertical) appears mirror-like, reflecting objects below. The region above the water cannot be seen except overhead, where the hemispherical field of view is compressed into a conical field known as Snell's window, whose angular diameter is twice the critical angle (cf. Fig. 6). The field of view above the water is theoretically 180° across, but seems less because as we look closer to the horizon, the vertical dimension is more strongly compressed by the refraction; e.g., by Eq. (3), for air-to-water incident angles of 90°, 80°, and 70°, the corresponding angles of refraction are 48.6° (θcr in Fig. 6), 47.6°, and 44.8°, indicating that the image of a point 20° above the horizon is 3.8° from the edge of Snell's window while the image of a point 10° above the horizon is only 1° from the edge.

Fig. 7, for example, is a photograph taken near the bottom of the shallow end of a swimming pool. What looks like a broad horizontal stripe on the right-hand wall consists of the lower edges of a row of orange tiles, and their reflections; this marks the water level, which can then be traced across the other wall. The swimmer has disturbed the surface above her, scrambling the lower half of her reflection, and distorting the reflection of the ladder (to the right). But most of the surface is still calm, giving a clear reflection of the tiled bottom of the pool. The space above the water is not visible except at the top of the frame, where the handles of the ladder are just discernible above the edge of Snell's window – within which the reflection of the bottom of the pool is only partial, but still noticeable in the photograph. One can even discern the color-fringing of the edge of Snell's window, due to variation of the refractive index, hence of the critical angle, with wavelength (see Dispersion).

The critical angle influences the angles at which gemstones are cut. The round "brilliant" cut, for example, is designed to refract light incident on the front facets, reflect it twice by TIR off the back facets, and transmit it out again through the front facets, so that the stone looks bright. Diamond (Fig. 8) is especially suitable for this treatment, because its high refractive index (about 2.42) and consequently small critical angle (about 24.5°) yield the desired behavior over a wide range of viewing angles. Cheaper materials that are similarly amenable to this treatment include cubic zirconia (index ≈ 2.15) and moissanite (non-isotropic, hence doubly refractive, with an index ranging from about 2.65 to 2.69, depending on direction and polarization); both of these are therefore popular as diamond simulants.

Evanescent wave

Further information: Evanescent wave § Total internal reflection of lightMathematically, waves are described in terms of time-varying fields, a "field" being a function of location in space. A propagating wave requires an "effort" field and a "flow" field, the latter being a vector (if we are working in two or three dimensions). The product of effort and flow is related to power (see System equivalence). For example, for sound waves in a non-viscous fluid, we might take the effort field as the pressure (a scalar), and the flow field as the fluid velocity (a vector). The product of these two is intensity (power per unit area). For electromagnetic waves, we shall take the effort field as the electric field E , and the flow field as the magnetizing field H. Both of these are vectors, and their vector product is again the intensity (see Poynting vector).

When a wave in (say) medium 1 is reflected off the interface between medium 1 and medium 2, the flow field in medium 1 is the vector sum of the flow fields due to the incident and reflected waves. If the reflection is oblique, the incident and reflected fields are not in opposite directions and therefore cannot cancel out at the interface; even if the reflection is total, either the normal component or the tangential component of the combined field (as a function of location and time) must be non-zero adjacent to the interface. Furthermore, the physical laws governing the fields will generally imply that one of the two components is continuous across the interface (that is, it does not suddenly change as we cross the interface); for example, for electromagnetic waves, one of the interface conditions is that the tangential component of H is continuous if there is no surface current. Hence, even if the reflection is total, there must be some penetration of the flow field into medium 2; and this, in combination with the laws relating the effort and flow fields, implies that there will also be some penetration of the effort field. The same continuity condition implies that the variation ("waviness") of the field in medium 2 will be synchronized with that of the incident and reflected waves in medium 1.

But, if the reflection is total, the spatial penetration of the fields into medium 2 must be limited somehow, or else the total extent and hence the total energy of those fields would continue to increase, draining power from medium 1. Total reflection of a continuing wavetrain permits some energy to be stored in medium 2, but does not permit a continuing transfer of power from medium 1 to medium 2.

Thus, using mostly qualitative reasoning, we can conclude that total internal reflection must be accompanied by a wavelike field in the "external" medium, traveling along the interface in synchronism with the incident and reflected waves, but with some sort of limited spatial penetration into the "external" medium; such a field may be called an evanescent wave.

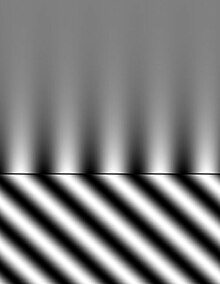

Fig. 9 shows the basic idea. The incident wave is assumed to be plane and sinusoidal. The reflected wave, for simplicity, is not shown. The evanescent wave travels to the right in lock-step with the incident and reflected waves, but its amplitude falls off with increasing distance from the interface.

(Two features of the evanescent wave in Fig. 9 are to be explained later: first, that the evanescent wave crests are perpendicular to the interface; and second, that the evanescent wave is slightly ahead of the incident wave.)

Frustrated total internal reflection (FTIR)

If the internal reflection is to be total, there must be no diversion of the evanescent wave. Suppose, for example, that electromagnetic waves incident from glass (with a higher refractive index) to air (with a lower refractive index) at a certain angle of incidence are subject to TIR. And suppose that we have a third medium (often identical to the first) whose refractive index is sufficiently high that, if the third medium were to replace the second, we would get a standard transmitted wavetrain for the same angle of incidence. Then, if the third medium is brought within a distance of a few wavelengths from the surface of the first medium, where the evanescent wave has significant amplitude in the second medium, then the evanescent wave is effectively refracted into the third medium, giving non-zero transmission into the third medium, and therefore less than total reflection back into the first medium. As the amplitude of the evanescent wave decays across the air gap, the transmitted waves are attenuated, so that there is less transmission, and therefore more reflection, than there would be with no gap; but as long as there is some transmission, the reflection is less than total. This phenomenon is called frustrated total internal reflection (where "frustrated" negates "total"), abbreviated "frustrated TIR" or "FTIR".

Frustrated TIR can be observed by looking into the top of a glass of water held in one's hand (Fig. 10). If the glass is held loosely, contact may not be sufficiently close and widespread to produce a noticeable effect. But if it is held more tightly, the ridges of one's fingerprints interact strongly with the evanescent waves, allowing the ridges to be seen through the otherwise totally reflecting glass-air surface.

The same effect can be demonstrated with microwaves, using paraffin wax as the "internal" medium (where the incident and reflected waves exist). In this case the permitted gap width might be (e.g.) 1 cm or several cm, which is easily observable and adjustable.

The term frustrated TIR also applies to the case in which the evanescent wave is scattered by an object sufficiently close to the reflecting interface. This effect, together with the strong dependence of the amount of scattered light on the distance from the interface, is exploited in total internal reflection microscopy.

The mechanism of FTIR is called evanescent-wave coupling, and is a good analog to visualize quantum tunneling. Due to the wave nature of matter, an electron has a non-zero probability of "tunneling" through a barrier, even if classical mechanics would say that its energy is insufficient. Similarly, due to the wave nature of light, a photon has a non-zero probability of crossing a gap, even if ray optics would say that its approach is too oblique.

Another reason why internal reflection may be less than total, even beyond the critical angle, is that the external medium may be "lossy" (less than perfectly transparent), in which case the external medium will absorb energy from the evanescent wave, so that the maintenance of the evanescent wave will draw power from the incident wave. The consequent less-than-total reflection is called attenuated total reflectance (ATR). This effect, and especially the frequency-dependence of the absorption, can be used to study the composition of an unknown external medium.

Derivation of evanescent wave

In a uniform plane sinusoidal electromagnetic wave, the electric field E has the form

| 5 |

where Ek is the (constant) complex amplitude vector, i is the imaginary unit, k is the wave vector (whose magnitude k is the angular wavenumber), r is the position vector, ω is the angular frequency, t is time, and it is understood that the real part of the expression is the physical field. The magnetizing field H has the same form with the same k and ω. The value of the expression is unchanged if the position r varies in a direction normal to k; hence k is normal to the wavefronts.

If ℓ is the component of r in the direction of k, the field (5) can be written If the argument of is to be constant, ℓ must increase at the velocity known as the phase velocity. This in turn is equal to where c is the phase velocity in the reference medium (taken as vacuum), and n is the local refractive index w.r.t. the reference medium. Solving for k gives i.e.

| 6 |

where is the wavenumber in vacuum.

From (5), the electric field in the "external" medium has the form

| 7 |

where kt is the wave vector for the transmitted wave (we assume isotropic media, but the transmitted wave is not yet assumed to be evanescent).

In Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z), let the region y < 0 have refractive index n1, and let the region y > 0 have refractive index n2. Then the xz plane is the interface, and the y axis is normal to the interface (Fig. 11). Let i and j be the unit vectors in the x and y directions respectively. Let the plane of incidence (containing the incident wave-normal and the normal to the interface) be the xy plane (the plane of the page), with the angle of incidence θi measured from j towards i. Let the angle of refraction, measured in the same sense, be θt ("t" for transmitted, reserving "r" for reflected).

From (6), the transmitted wave vector kt has magnitude n2k0. Hence, from the geometry, where the last step uses Snell's law. Taking the dot product with the position vector, we get so that Eq. (7) becomes

| 8 |

In the case of TIR, the angle θt does not exist in the usual sense. But we can still interpret (8) for the transmitted (evanescent) wave by allowing cos θt to be complex. This becomes necessary when we write cos θt in terms of sin θt, and thence in terms of sin θi using Snell's law: For θi greater than the critical angle, the value under the square-root symbol is negative, so that

| 9 |

To determine which sign is applicable, we substitute (9) into (8), obtaining

| 10 |

where the undetermined sign is the opposite of that in (9). For an evanescent transmitted wave – that is, one whose amplitude decays as y increases – the undetermined sign in (10) must be minus, so the undetermined sign in (9) must be plus.

With the correct sign, the result (10) can be abbreviated

| 11 |

where

| 12 |

and k0 is the wavenumber in vacuum, i.e.

So the evanescent wave is a plane sinewave traveling in the x direction, with an amplitude that decays exponentially in the y direction (Fig. 9). It is evident that the energy stored in this wave likewise travels in the x direction and does not cross the interface. Hence the Poynting vector generally has a component in the x direction, but its y component averages to zero (although its instantaneous y component is not identically zero).

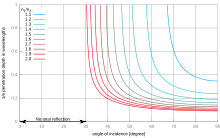

Eq. (11) indicates that the amplitude of the evanescent wave falls off by a factor e as the coordinate y (measured from the interface) increases by the distance commonly called the "penetration depth" of the evanescent wave. Taking reciprocals of the first equation of (12), we find that the penetration depth is where λ0 is the wavelength in vacuum, i.e. Dividing the numerator and denominator by n2 yields where is the wavelength in the second (external) medium. Hence we can plot d in units of λ2 as a function of the angle of incidence for various values of (Fig. 12). As θi decreases towards the critical angle, the denominator approaches zero, so that d increases without limit – as is to be expected, because as soon as θi is less than critical, uniform plane waves are permitted in the external medium. As θi approaches 90° (grazing incidence), d approaches a minimum For incidence from water to air, or common glass to air, dmin is not much different from λ2/(2π). But d is larger at smaller angles of incidence (Fig. 12), and the amplitude may still be significant at distances of several times d; for example, because e is just greater than 0.01, the evanescent wave amplitude within a distance 4.6d of the interface is at least 1% of its value at the interface. Hence, speaking loosely, we tend to say that the evanescent wave amplitude is significant within "a few wavelengths" of the interface.

Phase shifts

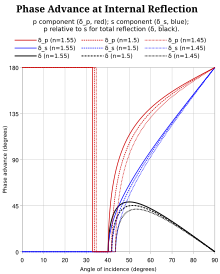

Between 1817 and 1823, Augustin-Jean Fresnel discovered that total internal reflection is accompanied by a non-trivial phase shift (that is, a phase shift that is not restricted to 0° or 180°), as the Fresnel reflection coefficient acquires a non-zero imaginary part. We shall now explain this effect for electromagnetic waves in the case of linear, homogeneous, isotropic, non-magnetic media. The phase shift turns out to be an advance, which grows as the incidence angle increases beyond the critical angle, but which depends on the polarization of the incident wave.

In equations (5), (7), (8), (10), and (11), we advance the phase by the angle ϕ if we replace ωt by ωt + ϕ (that is, if we replace −ωt by −ωt − ϕ), with the result that the (complex) field is multiplied by e. So a phase advance is equivalent to multiplication by a complex constant with a negative argument. This becomes more obvious when (e.g.) the field (5) is factored as where the last factor contains the time dependence.

To represent the polarization of the incident, reflected, or transmitted wave, the electric field adjacent to an interface can be resolved into two perpendicular components, known as the s and p components, which are parallel to the surface and the plane of incidence respectively; in other words, the s and p components are respectively square and parallel to the plane of incidence.

For each component of polarization, the incident, reflected, or transmitted electric field (E in Eq. (5)) has a certain direction and can be represented by its (complex) scalar component in that direction. The reflection or transmission coefficient can then be defined as a ratio of complex components at the same point, or at infinitesimally separated points on opposite sides of the interface. But, in order to fix the signs of the coefficients, we must choose positive senses for the "directions". For the s components, the obvious choice is to say that the positive directions of the incident, reflected, and transmitted fields are all the same (e.g., the z direction in Fig. 11). For the p components, this article adopts the convention that the positive directions of the incident, reflected, and transmitted fields are inclined towards the same medium (that is, towards the same side of the interface, e.g. like the red arrows in Fig. 11). But the reader should be warned that some books use a different convention for the p components, causing a different sign in the resulting formula for the reflection coefficient.

For the s polarization, let the reflection and transmission coefficients be rs and ts respectively. For the p polarization, let the corresponding coefficients be rp and tp . Then, for linear, homogeneous, isotropic, non-magnetic media, the coefficients are given by

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

(For a derivation of the above, see Fresnel equations § Theory.)

Now we suppose that the transmitted wave is evanescent. With the correct sign (+), substituting (9) into (13) gives where that is, n is the index of the "internal" medium relative to the "external" one, or the index of the internal medium if the external one is vacuum. So the magnitude of rs is 1, and the argument of rs is which gives a phase advance of

| 17 |

Making the same substitution in (14), we find that ts has the same denominator as rs with a positive real numerator (instead of a complex conjugate numerator) and therefore has half the argument of rs, so that the phase advance of the evanescent wave is half that of the reflected wave.

With the same choice of sign, substituting (9) into (15) gives whose magnitude is 1, and whose argument is which gives a phase advance of

| 18 |

Making the same substitution in (16), we again find that the phase advance of the evanescent wave is half that of the reflected wave.

Equations (17) and (18) apply when θc ≤ θi < 90°, where θi is the angle of incidence, and θc is the critical angle arcsin (1/n). These equations show that

- each phase advance is zero at the critical angle (for which the numerator is zero);

- each phase advance approaches 180° as θi → 90°; and

- δp > δs at intermediate values of θi (because the factor n is in the numerator of (18) and the denominator of (17)).

For θi ≤ θc, the reflection coefficients are given by equations (13) and (15) and are real, so that the phase shift is either 0° (if the coefficient is positive) or 180° (if the coefficient is negative).

In (13), if we put (Snell's law) and multiply the numerator and denominator by 1/n1 sin θt, we obtain

| 19 |

which is positive for all angles of incidence with a transmitted ray (since θt > θi), giving a phase shift δs of zero.

If we do likewise with (15), the result is easily shown to be equivalent to

| 20 |

which is negative for small angles (that is, near normal incidence), but changes sign at Brewster's angle, where θi and θt are complementary. Thus the phase shift δp is 180° for small θi but switches to 0° at Brewster's angle. Combining the complementarity with Snell's law yields θi = arctan (1/n) as Brewster's angle for dense-to-rare incidence.

(Equations (19) and (20) are known as Fresnel's sine law and Fresnel's tangent law. Both reduce to 0/0 at normal incidence, but yield the correct results in the limit as θi → 0. That they have opposite signs as we approach normal incidence is an obvious disadvantage of the sign convention used in this article; the corresponding advantage is that they have the same signs at grazing incidence.)

That completes the information needed to plot δs and δp for all angles of incidence. This is done in Fig. 13, with δp in red and δs in blue, for three refractive indices. On the angle-of-incidence scale (horizontal axis), Brewster's angle is where δp (red) falls from 180° to 0°, and the critical angle is where both δp and δs (red and blue) start to rise again. To the left of the critical angle is the region of partial reflection, where both reflection coefficients are real (phase 0° or 180°) with magnitudes less than 1. To the right of the critical angle is the region of total reflection, where both reflection coefficients are complex with magnitudes equal to 1. In that region, the black curves show the phase advance of the p component relative to the s component: It can be seen that a refractive index of 1.45 is not enough to give a 45° phase difference, whereas a refractive index of 1.5 is enough (by a slim margin) to give a 45° phase difference at two angles of incidence: about 50.2° and 53.3°.

This 45° relative shift is employed in Fresnel's invention, now known as the Fresnel rhomb, in which the angles of incidence are chosen such that the two internal reflections cause a total relative phase shift of 90° between the two polarizations of an incident wave. This device performs the same function as a birefringent quarter-wave plate, but is more achromatic (that is, the phase shift of the rhomb is less sensitive to wavelength). Either device may be used, for instance, to transform linear polarization to circular polarization (which Fresnel also discovered) and conversely.

Further information: Fresnel rhombIn Fig. 13, δ is computed by a final subtraction; but there are other ways of expressing it. Fresnel himself, in 1823, gave a formula for cos δ. Born and Wolf (1970, p. 50) derive an expression for tan (δ/2) and find its maximum analytically.

For TIR of a beam with finite width, the variation in the phase shift with the angle of incidence gives rise to the Goos–Hänchen effect, which is a lateral shift of the reflected beam within the plane of incidence. This effect applies to linear polarization in the s or p direction. The Imbert–Fedorov effect is an analogous effect for circular or elliptical polarization and produces a shift perpendicular to the plane of incidence.

Applications

Further information: Prism (optics) § Reflective·prismsOptical fibers exploit total internal reflection to carry signals over long distances with little attenuation. They are used in telecommunication cables, and in image-forming fiberscopes such as colonoscopes.

In the catadioptric Fresnel lens, invented by Augustin-Jean Fresnel for use in lighthouses, the outer prisms use TIR to deflect light from the lamp through a greater angle than would be possible with purely refractive prisms, but with less absorption of light (and less risk of tarnishing) than with conventional mirrors.

Other reflecting prisms that use TIR include the following (with some overlap between the categories):

- Image-erecting prisms for binoculars and spotting scopes include paired 45°-90°-45° Porro prisms (Fig. 14), the Porro–Abbe prism, the inline Koenig and Abbe–Koenig prisms, and the compact inline Schmidt–Pechan prism. (The last consists of two components, of which one is a kind of Bauernfeind prism, which requires a reflective coating on one of its two reflecting faces, due to a sub-critical angle of incidence.) These prisms have the additional function of folding the optical path from the objective lens to the prime focus, reducing the overall length for a given primary focal length.

- A prismatic star diagonal for an astronomical telescope may consist of a single Porro prism (configured for a single reflection, giving a mirror-reversed image) or an Amici roof prism (which gives a non-reversed image).

- Roof prisms use TIR at two faces meeting at a sharp 90° angle. This category includes the Koenig, Abbe–Koenig, Schmidt–Pechan, and Amici types (already mentioned), and the roof pentaprism used in SLR cameras; the last of these requires a reflective coating on one non-TIR face.

- A prismatic corner reflector uses three total internal reflections to reverse the direction of incoming light.

- The Dove prism gives an inline view with mirror-reversal.

Polarizing prisms: Although the Fresnel rhomb, which converts between linear and elliptical polarization, is not birefringent (doubly refractive), there are other kinds of prisms that combine birefringence with TIR in such a way that light of a particular polarization is totally reflected while light of the orthogonal polarization is at least partly transmitted. Examples include the Nicol prism, Glan–Thompson prism, Glan–Foucault prism (or "Foucault prism"), and Glan–Taylor prism.

Refractometers, which measure refractive indices, often use the critical angle.

Rain sensors for automatic windscreen/windshield wipers have been implemented using the principle that total internal reflection will guide an infrared beam from a source to a detector if the outer surface of the windshield is dry, but any water drops on the surface will divert some of the light.

Edge-lit LED panels, used (e.g.) for backlighting of LCD computer monitors, exploit TIR to confine the LED light to the acrylic glass pane, except that some of the light is scattered by etchings on one side of the pane, giving an approximately uniform luminous emittance.

Total internal reflection microscopy (TIRM) uses the evanescent wave to illuminate small objects close to the reflecting interface. The consequent scattering of the evanescent wave (a form of frustrated TIR), makes the objects appear bright when viewed from the "external" side. In the total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (TIRFM), instead of relying on simple scattering, we choose an evanescent wavelength short enough to cause fluorescence (Fig. 15). The high sensitivity of the illumination to the distance from the interface allows measurement of extremely small displacements and forces.

A beam-splitter cube uses frustrated TIR to divide the power of the incoming beam between the transmitted and reflected beams. The width of the air gap (or low-refractive-index gap) between the two prisms can be made adjustable, giving higher transmission and lower reflection for a narrower gap, or higher reflection and lower transmission for a wider gap.

Optical modulation can be accomplished by means of frustrated TIR with a rapidly variable gap. As the transmission coefficient is highly sensitive to the gap width (the function being approximately exponential until the gap is almost closed), this technique can achieve a large dynamic range.

Optical fingerprinting devices have used frustrated TIR to record images of persons' fingerprints without the use of ink (cf. Fig. 11).

Gait analysis can be performed by using frustrated TIR with a high-speed camera, to capture and analyze footprints.

A gonioscope, used in optometry and ophthalmology for the diagnosis of glaucoma, suppresses TIR in order to look into the angle between the iris and the cornea. This view is usually blocked by TIR at the cornea-air interface. The gonioscope replaces the air with a higher-index medium, allowing transmission at oblique incidence, typically followed by reflection in a "mirror", which itself may be implemented using TIR.

Some multi-touch interactive tables and whiteboards utilise FTIR to detect fingers touching the screen. An infrared camera is placed behind the screen surface, which is edge-lit by infrared LEDs; when touching the surface FTIR causes some of the infrared light to escape the screen plane, and the camera sees this as bright areas. Computer vision software is then used to translate this into a series of coordinates and gestures.

History

Discovery

The surprisingly comprehensive and largely correct explanations of the rainbow by Theodoric of Freiberg (written between 1304 and 1310) and Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (completed by 1309), although sometimes mentioned in connection with total internal reflection (TIR), are of dubious relevance because the internal reflection of sunlight in a spherical raindrop is not total. But, according to Carl Benjamin Boyer, Theodoric's treatise on the rainbow also classified optical phenomena under five causes, the last of which was "a total reflection at the boundary of two transparent media". Theodoric's work was forgotten until it was rediscovered by Giovanni Battista Venturi in 1814.

Theodoric having fallen into obscurity, the discovery of TIR was generally attributed to Johannes Kepler, who published his findings in his Dioptrice in 1611. Although Kepler failed to find the true law of refraction, he showed by experiment that for air-to-glass incidence, the incident and refracted rays rotated in the same sense about the point of incidence, and that as the angle of incidence varied through ±90°, the angle of refraction (as we now call it) varied through ±42°. He was also aware that the incident and refracted rays were interchangeable. But these observations did not cover the case of a ray incident from glass to air at an angle beyond 42°, and Kepler promptly concluded that such a ray could only be reflected.

René Descartes rediscovered the law of refraction and published it in his Dioptrique of 1637. In the same work he mentioned the senses of rotation of the incident and refracted rays and the condition of TIR. But he neglected to discuss the limiting case, and consequently failed to give an expression for the critical angle, although he could easily have done so.

Huygens and Newton: Rival explanations

Christiaan Huygens, in his Treatise on Light (1690), paid much attention to the threshold at which the incident ray is "unable to penetrate into the other transparent substance". Although he gave neither a name nor an algebraic expression for the critical angle, he gave numerical examples for glass-to-air and water-to-air incidence, noted the large change in the angle of refraction for a small change in the angle of incidence near the critical angle, and cited this as the cause of the rapid increase in brightness of the reflected ray as the refracted ray approaches the tangent to the interface. Huygens' insight is confirmed by modern theory: in Eqs. (13) and (15) above, there is nothing to say that the reflection coefficients increase exceptionally steeply as θt approaches 90°, except that, according to Snell's law, θt itself is an increasingly steep function of θi.

Huygens offered an explanation of TIR within the same framework as his explanations of the laws of rectilinear propagation, reflection, ordinary refraction, and even the extraordinary refraction of "Iceland crystal" (calcite). That framework rested on two premises: first, every point crossed by a propagating wavefront becomes a source of secondary wavefronts ("Huygens' principle"); and second, given an initial wavefront, any subsequent position of the wavefront is the envelope (common tangent surface) of all the secondary wavefronts emitted from the initial position. All cases of reflection or refraction by a surface are then explained simply by considering the secondary waves emitted from that surface. In the case of refraction from a medium of slower propagation to a medium of faster propagation, there is a certain obliquity of incidence beyond which it is impossible for the secondary wavefronts to form a common tangent in the second medium; this is what we now call the critical angle. As the incident wavefront approaches this critical obliquity, the refracted wavefront becomes concentrated against the refracting surface, augmenting the secondary waves that produce the reflection back into the first medium.

Huygens' system even accommodated partial reflection at the interface between different media, albeit vaguely, by analogy with the laws of collisions between particles of different sizes. However, as long as the wave theory continued to assume longitudinal waves, it had no chance of accommodating polarization, hence no chance of explaining the polarization-dependence of extraordinary refraction, or of the partial reflection coefficient, or of the phase shift in TIR.

Isaac Newton rejected the wave explanation of rectilinear propagation, believing that if light consisted of waves, it would "bend and spread every way" into the shadows. His corpuscular theory of light explained rectilinear propagation more simply, and it accounted for the ordinary laws of refraction and reflection, including TIR, on the hypothesis that the corpuscles of light were subject to a force acting perpendicular to the interface. In this model, for dense-to-rare incidence, the force was an attraction back towards the denser medium, and the critical angle was the angle of incidence at which the normal velocity of the approaching corpuscle was just enough to reach the far side of the force field; at more oblique incidence, the corpuscle would be turned back. Newton gave what amounts to a formula for the critical angle, albeit in words: "as the Sines are which measure the Refraction, so is the Sine of Incidence at which the total Reflexion begins, to the Radius of the Circle".

Newton went beyond Huygens in two ways. First, not surprisingly, Newton pointed out the relationship between TIR and dispersion: when a beam of white light approaches a glass-to-air interface at increasing obliquity, the most strongly-refracted rays (violet) are the first to be "taken out" by "total Reflexion", followed by the less-refracted rays. Second, he observed that total reflection could be frustrated (as we now say) by laying together two prisms, one plane and the other slightly convex; and he explained this simply by noting that the corpuscles would be attracted not only to the first prism, but also to the second.

In two other ways, however, Newton's system was less coherent. First, his explanation of partial reflection depended not only on the supposed forces of attraction between corpuscles and media, but also on the more nebulous hypothesis of "Fits of easy Reflexion" and "Fits of easy Transmission". Second, although his corpuscles could conceivably have "sides" or "poles", whose orientations could conceivably determine whether the corpuscles suffered ordinary or extraordinary refraction in "Island-Crystal", his geometric description of the extraordinary refraction was theoretically unsupported and empirically inaccurate.

Laplace, Malus, and attenuated total reflectance (ATR)

William Hyde Wollaston, in the first of a pair of papers read to the Royal Society of London in 1802, reported his invention of a refractometer based on the critical angle of incidence from an internal medium of known "refractive power" (refractive index) to an external medium whose index was to be measured. With this device, Wollaston measured the "refractive powers" of numerous materials, some of which were too opaque to permit direct measurement of an angle of refraction. Translations of his papers were published in France in 1803, and apparently came to the attention of Pierre-Simon Laplace.

According to Laplace's elaboration of Newton's theory of refraction, a corpuscle incident on a plane interface between two homogeneous isotropic media was subject to a force field that was symmetrical about the interface. If both media were transparent, total reflection would occur if the corpuscle were turned back before it exited the field in the second medium. But if the second medium were opaque, reflection would not be total unless the corpuscle were turned back before it left the first medium; this required a larger critical angle than the one given by Snell's law, and consequently impugned the validity of Wollaston's method for opaque media. Laplace combined the two cases into a single formula for the relative refractive index in terms of the critical angle (minimum angle of incidence for TIR). The formula contained a parameter which took one value for a transparent external medium and another value for an opaque external medium. Laplace's theory further predicted a relationship between refractive index and density for a given substance.

In 1807, Laplace's theory was tested experimentally by his protégé, Étienne-Louis Malus. Taking Laplace's formula for the refractive index as given, and using it to measure the refractive index of beeswax in the liquid (transparent) state and the solid (opaque) state at various temperatures (hence various densities), Malus verified Laplace's relationship between refractive index and density.

But Laplace's theory implied that if the angle of incidence exceeded his modified critical angle, the reflection would be total even if the external medium was absorbent. Clearly this was wrong: in Eqs. (12) above, there is no threshold value of the angle θi beyond which κ becomes infinite; so the penetration depth of the evanescent wave (1/κ) is always non-zero, and the external medium, if it is at all lossy, will attenuate the reflection. As to why Malus apparently observed such an angle for opaque wax, we must infer that there was a certain angle beyond which the attenuation of the reflection was so small that ATR was visually indistinguishable from TIR.

Fresnel and the phase shift

Fresnel came to the study of total internal reflection through his research on polarization. In 1811, François Arago discovered that polarized light was apparently "depolarized" in an orientation-dependent and color-dependent manner when passed through a slice of doubly-refractive crystal: the emerging light showed colors when viewed through an analyzer (second polarizer). Chromatic polarization, as this phenomenon came to be called, was more thoroughly investigated in 1812 by Jean-Baptiste Biot. In 1813, Biot established that one case studied by Arago, namely quartz cut perpendicular to its optic axis, was actually a gradual rotation of the plane of polarization with distance.

In 1816, Fresnel offered his first attempt at a wave-based theory of chromatic polarization. Without (yet) explicitly invoking transverse waves, his theory treated the light as consisting of two perpendicularly polarized components. In 1817 he noticed that plane-polarized light seemed to be partly depolarized by total internal reflection, if initially polarized at an acute angle to the plane of incidence. By including total internal reflection in a chromatic-polarization experiment, he found that the apparently depolarized light was a mixture of components polarized parallel and perpendicular to the plane of incidence, and that the total reflection introduced a phase difference between them. Choosing an appropriate angle of incidence (not yet exactly specified) gave a phase difference of 1/8 of a cycle. Two such reflections from the "parallel faces" of "two coupled prisms" gave a phase difference of 1/4 of a cycle. In that case, if the light was initially polarized at 45° to the plane of incidence and reflection, it appeared to be completely depolarized after the two reflections. These findings were reported in a memoir submitted and read to the French Academy of Sciences in November 1817.

In 1821, Fresnel derived formulae equivalent to his sine and tangent laws (Eqs. (19) and (20), above) by modeling light waves as transverse elastic waves with vibrations perpendicular to what had previously been called the plane of polarization. Using old experimental data, he promptly confirmed that the equations correctly predicted the direction of polarization of the reflected beam when the incident beam was polarized at 45° to the plane of incidence, for light incident from air onto glass or water. The experimental confirmation was reported in a "postscript" to the work in which Fresnel expounded his mature theory of chromatic polarization, introducing transverse waves. Details of the derivation were given later, in a memoir read to the academy in January 1823. The derivation combined conservation of energy with continuity of the tangential vibration at the interface, but failed to allow for any condition on the normal component of vibration.

Meanwhile, in a memoir submitted in December 1822, Fresnel coined the terms linear polarization, circular polarization, and elliptical polarization. For circular polarization, the two perpendicular components were a quarter-cycle (±90°) out of phase.

The new terminology was useful in the memoir of January 1823, containing the detailed derivations of the sine and tangent laws: in that same memoir, Fresnel found that for angles of incidence greater than the critical angle, the resulting reflection coefficients were complex with unit magnitude. Noting that the magnitude represented the amplitude ratio as usual, he guessed that the argument represented the phase shift, and verified the hypothesis by experiment. The verification involved

- calculating the angle of incidence that would introduce a total phase difference of 90° between the s and p components, for various numbers of total internal reflections at that angle (generally there were two solutions),

- subjecting light to that number of total internal reflections at that angle of incidence, with an initial linear polarization at 45° to the plane of incidence, and

- checking that the final polarization was circular.

This procedure was necessary because, with the technology of the time, one could not measure the s and p phase-shifts directly, and one could not measure an arbitrary degree of ellipticality of polarization, such as might be caused by the difference between the phase shifts. But one could verify that the polarization was circular, because the brightness of the light was then insensitive to the orientation of the analyzer.

For glass with a refractive index of 1.51, Fresnel calculated that a 45° phase difference between the two reflection coefficients (hence a 90° difference after two reflections) required an angle of incidence of 48°37' or 54°37'. He cut a rhomb to the latter angle and found that it performed as expected. Thus the specification of the Fresnel rhomb was completed. Similarly, Fresnel calculated and verified the angle of incidence that would give a 90° phase difference after three reflections at the same angle, and four reflections at the same angle. In each case there were two solutions, and in each case he reported that the larger angle of incidence gave an accurate circular polarization (for an initial linear polarization at 45° to the plane of reflection). For the case of three reflections he also tested the smaller angle, but found that it gave some coloration due to the proximity of the critical angle and its slight dependence on wavelength. (Compare Fig. 13 above, which shows that the phase difference δ is more sensitive to the refractive index for smaller angles of incidence.)

For added confidence, Fresnel predicted and verified that four total internal reflections at 68°27' would give an accurate circular polarization if two of the reflections had water as the external medium while the other two had air, but not if the reflecting surfaces were all wet or all dry.

Fresnel's deduction of the phase shift in TIR is thought to have been the first occasion on which a physical meaning was attached to the argument of a complex number. Although this reasoning was applied without the benefit of knowing that light waves were electromagnetic, it passed the test of experiment, and survived remarkably intact after James Clerk Maxwell changed the presumed nature of the waves. Meanwhile, Fresnel's success inspired James MacCullagh and Augustin-Louis Cauchy, beginning in 1836, to analyze reflection from metals by using the Fresnel equations with a complex refractive index. The imaginary part of the complex index represents absorption.

The term critical angle, used for convenience in the above narrative, is anachronistic: it apparently dates from 1873.

In the 20th century, quantum electrodynamics reinterpreted the amplitude of an electromagnetic wave in terms of the probability of finding a photon. In this framework, partial transmission and frustrated TIR concern the probability of a photon crossing a boundary, and attenuated total reflectance concerns the probability of a photon being absorbed on the other side.

Research into the more subtle aspects of the phase shift in TIR, including the Goos–Hänchen and Imbert–Fedorov effects and their quantum interpretations, has continued into the 21st century.

Gallery

-

An Indian triggerfish and its total reflection in the water's surface

An Indian triggerfish and its total reflection in the water's surface

-

Total reflection of a paintbrush by the water–air surface in a glass

Total reflection of a paintbrush by the water–air surface in a glass

-

Total internal reflection of a green laser in the stem of a wine glass

Total internal reflection of a green laser in the stem of a wine glass

See also

- Attenuated total reflectance

- Evanescent field

- Fiberscope

- Fresnel equations

- Fresnel lens

- Fresnel rhomb

- Goos–Hänchen effect

- Imbert–Fedorov effect

- Optical fiber

- Polarization (waves)

- Snell's window

- TIR fluorescence microscope

- TIR microscopy

- Total external reflection

Notes

- Birefringent media, such as calcite, are non-isotropic (anisotropic). When we say that the extraordinary refraction of a calcite crystal "violates Snell's law", we mean that Snell's law does not apply to the extraordinary ray, because the direction of this ray inside the crystal generally differs from that of the associated wave-normal (Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, p. 65, Art. 24), and because the wave-normal speed is itself dependent on direction. (Note that the cited passage contains a translation error: in the phrase "conjugate with respect to diameters which are not in the straight line AB", the word "not" is unsupported by Huygens' original French and is geometrically incorrect.)

- According to Eqs. (13) and (15), reflection is total for incidence at the critical angle. On that basis, Fig. 5 ought to show a fully reflected ray, and no tangential ray, for incidence at θc. But, due to diffraction, an incident beam of finite width cannot have a single angle of incidence; there must be some divergence of the beam. Moreover, the graph of the reflection coefficient vs. the angle of incidence becomes vertical at θc (Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 527), so that a small divergence of the beam causes a large loss of reflection. Similarly, near the critical angle, a small divergence in the angle of incidence causes a large divergence in the angle of refraction (Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, p. 41); the tangential refracted ray should therefore be taken only as a limiting case.

- For non-isotropic media, Eq. (1) still describes the law of refraction in terms of wave-normal directions and speeds, but the range of applicability of that law is determined by the constraints on the ray directions (Buchwald, 1989, p. 29).

- The quoted range varies because of different crystal polytypes.

- Power "per unit area" is appropriate for fields in three dimensions. In two dimensions, we might want the product of effort and flow to be power per unit length. In one dimension, or in a lumped-element model, we might want it to be simply power.

- We assume that the equations describing the fields are linear.

- The above form (5) is typically used by physicists. Electrical engineers typically prefer the form that is, they not only use j instead of i for the imaginary unit, but also change the sign of the exponent, with the result that the whole expression is replaced by its complex conjugate, leaving the real part unchanged. The electrical engineers' form and the formulae derived therefrom may be converted to the physicists' convention by substituting −i for j (Stratton, 1941, pp. vii–viii).

- We assume that there are no Doppler shifts, so that ω does not change at interfaces between media.

- If we correctly convert this to the electrical engineering convention, we get −j√⋯ on the right-hand side of (9), which is not the principal square root. So it is not valid to assume, a priori, that what mathematicians call the "principal square root" is the physically applicable one.

- In the electrical engineering convention, the time-dependent factor is e, so that a phase advance corresponds to multiplication by a complex constant with a positive argument. This article, however, uses the physics convention, with the time-dependent factor e.

- The s originally comes from the German senkrecht, meaning "perpendicular" (to the plane of incidence). The alternative mnemonics in the text are perhaps more suitable for English speakers.

- In other words, for both polarizations, this article uses the convention that the positive directions of the incident, reflected, and transmitted fields are all the same for whichever field is normal to the plane of incidence; this is the E field for the s polarization, and the H field for the p polarization.

- This nomenclature follows Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 526–529. Some authors, however, use the reciprocal refractive index and therefore obtain different forms for our Eqs. (17) and (18). Examples include Born & Wolf [1970, p. 49, eqs. (60)] and Stratton [1941, p. 499, eqs. (43)]. Furthermore, Born & Wolf define δ⊥ and δ∥ as arguments rather than phase shifts, causing a change of sign.

- It is merely fortuitous that the principal square root turns out to be the correct one in the present situation, and only because we use the time-dependent factor e. If we instead used the electrical engineers' time-dependent factor e, choosing the principal square root would yield the same argument for the reflection coefficient, but this would be interpreted as the opposite phase shift, which would be wrong. But if we choose the square root so that the transmitted field is evanescent, we get the right phase shift with either time-dependent factor.

- The more familiar formula arctan n is for rare-to-dense incidence. In both cases, n is the refractive index of the denser medium relative to the rarer medium.

- For an external ray incident on a spherical raindrop, the refracted ray is in the plane of the incident ray and the center of the drop, and the angle of refraction is less than the critical angle for water-air incidence; but this angle of refraction, by the spherical symmetry, is also the angle of incidence for the internal reflection, which is therefore less than total. Moreover, if that reflection were total, all subsequent internal reflections would have the same angle of incidence (due to the symmetry) and would also be total, so that the light would never escape to produce a visible bow.

- Hence, where Fresnel says that after total internal reflection at the appropriate incidence, the wave polarized parallel to the plane of incidence is "behind" by 1/8 of a cycle (quoted by Buchwald, 1989, p. 381), he refers to the wave whose plane of polarization is parallel to the plane of incidence, i.e. the wave whose vibration is perpendicular to that plane, i.e. what we now call the s component.

References

- ^ R.P. Feynman, R.B. Leighton, and M. Sands, 1963–2013, The Feynman Lectures on Physics, California Institute of Technology, Volume II, § 33-6.

- Antich, Peter P.; Anderson, Jon A.; Ashman, Richard B.; Dowdey, James E.; Gonzales, Jerome; Murry, Robert C.; Zerwekh, Joseph E.; Pak, Charles Y. C. (2009). "Measurement of mechanical properties of bone material in vitro by ultrasound reflection: Methodology and comparison with ultrasound transmission". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 6 (4): 417–426. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650060414. PMID 1858525. S2CID 6914223..

- Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 11.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 527. (The refracted beam becomes fainter in terms of total power, but not necessarily in terms of visibility, because the beam also becomes narrower as it becomes more nearly tangential.)

- Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 26.

- Cf. Thomas Young in the Quarterly Review, April 1814, reprinted in T. Young (ed. G. Peacock), Miscellaneous Works of the late Thomas Young, London: J. Murray, 1855, vol. 1, at p. 263.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, pp. 12–13.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, p. 38.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 13; Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 9–10. This definition uses vacuum as the "reference medium". In principle, any isotropic medium can be chosen as the reference. For some purposes it is convenient to choose air, in which the speed of light is about 0.03% lower than in vacuum (Rutten and van Venrooij, 2002, pp. 10, 352). The present article, however, chooses vacuum.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 25.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 10, 25.

- Cf. D.K. Lynch (1 February 2015), "Snell's window in wavy water", Applied Optics, 54 (4): B8–B11, doi:10.1364/AO.54.0000B8.

- Huygens (1690, tr. Thompson, p. 41), for glass-to-air incidence, noted that if the obliqueness of the incident ray is only 1° short of critical, the refracted ray is more than 11° from the tangent. N.B.: Huygens' definition of the "angle of incidence" is the complement of the modern definition.

- J.R. Graham, "Can you cut a gem design for tilt brightness?", International Gem Society, accessed 21 March 2019; archived 14 December 2018.

- 'PJS' (author), "Sound Pressure, Sound Power, and Sound Intensity: What's the difference?" Siemens PLM Community, accessed 10 April 2019; archived 10 April 2019.

- Stratton, 1941, pp. 131–7.

- Stratton, 1941, p. 37.

- ^ Cf. Harvard Natural Sciences Lecture Demonstrations, "Frustrated Total Internal Reflection", accessed 9 April 2019; archived 2 August 2018.

- ^ R. Ehrlich, 1997, Why Toast Lands Jelly-side Down: Zen and the Art of Physics Demonstrations, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-02891-0, p. 182, accessed 26 March 2019.

- R. Bowley, 2009, "Total Internal Reflection" (4-minute video), Sixty Symbols, Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham, from 1:25.

- ^ E.J. Ambrose (24 November 1956), "A surface contact microscope for the study of cell movements", Nature, 178 (4543): 1194, Bibcode:1956Natur.178.1194A, doi:10.1038/1781194a0, PMID 13387666, S2CID 4290898.

- Van Rosum, Aernout; Van Den Berg, Ed (May 2021). "Using frustrated internal reflection as an analog to quantum tunneling". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1929 (1): 012050. Bibcode:2021JPhCS1929a2050V. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1929/1/012050. S2CID 235591328.

- Thermo Fisher Scientific, "FTIR Sample Techniques: Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR)", accessed 9 April 2019.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 228.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, pp. 16–17, eqs. (20), (21).

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 47, eq. (54), where their n is our (not our ).

- Stratton, 1941, p. 499; Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 48.

- ^ Laboratory of Cold Atoms Near Surfaces (Jagiellonian University), "Evanescent wave properties", accessed 11 April 2019; archived 28 April 2018. (N.B.: This page uses z for the coordinate normal to the interface, and the superscripts ⊥ and ∥ for the s ("TE") and p polarizations, respectively. Pages on this site use the time-dependent factor e — that is, the electrical engineers' time-dependent factor with the physicists' symbol for the imaginary unit.)

- Hecht, 2017, p. 136.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 16.

- Whittaker, 1910, pp. 132, 135–136.

- One notable authority that uses the "different" convention (but without taking it very far) is The Feynman Lectures on Physics, at volume I, eq. (33.8) (for B) and volume II, Figs. 33-6 and 33-7.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 40, eqs. (20), (21), where the subscript ⊥ corresponds to s, and ∥ to p.

- ^ Cf. Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 529.

- "The phase of the polarization in which the magnetic field is parallel to the interface is advanced with respect to that of the other polarization." – Fitzpatrick, 2013, p. 140; Fitzpatrick, 2013a; emphasis added.

- Fresnel, 1866, pp. 773, 789n.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 40, eqs. (21a); Hecht, 2017, p. 125, eq. (4.42); Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 524, eqs. (25a).

- Fresnel, 1866, pp. 757, 789n.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 40, eqs. (21a); Hecht, 2017, p. 125, eq. (4.43); Jenkins & White, 1976, p. 524, eqs. (25a).

- Whittaker, 1910, p. 134; Darrigol, 2012, p. 213.

- Stratton, 1941, p. 500, eq. (44). The corresponding expression in Born & Wolf (1970, p. 50) is the other way around because the terms represent arguments rather than phase shifts.

- Buchwald, 1989, pp. 394, 453; Fresnel, 1866, pp. 759, 786–787, 790.

- P.R. Berman, 2012, "Goos-Hänchen effect", Scholarpedia 7 (3): 11584, § 2.1, especially eqs. (1) to (3). Note that Berman's n is the reciprocal of the n in the present article.

- ^ Bliokh, K. Y.; Aiello, A. (2013). "Goos–Hänchen and Imbert–Fedorov beam shifts: An overview". Journal of Optics. 15 (1): 014001. arXiv:1210.8236. Bibcode:2013JOpt...15a4001B. doi:10.1088/2040-8978/15/1/014001. S2CID 118380597.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 40–42.

- Rudd, W. W. (1971). "Fiberoptic Colonoscopy: A Dramatic Advance in Colon Surgery". Canadian Family Physician. 17 (12): 42–45. PMC 2370306. PMID 20468707.

- Levitt, 2013, pp. 79–80.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 26–7 (Porro, Dove, 90° Amici, corner reflector, Lummer-Brodhun); Born & Wolf, 1970, pp. 240–41 (Porro, Koenig), 243–4 (Dove).

- Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 241.

- Born & Wolf, 1970, pp. 690–91.

- R. Nave, "Prisms for Polarization" (Nicol, Glan–Foucault), Georgia State University, accessed 27 March 2019; archived 25 March 2019.

- Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 510–11 (Nicol, Glan–Thompson, "Foucault").

- J.F. Archard; A.M. Taylor (December 1948), "Improved Glan-Foucault prism", Journal of Scientific Instruments, 25 (12): 407–9, Bibcode:1948JScI...25..407A, doi:10.1088/0950-7671/25/12/304.

- Buchwald, 1989, pp. 19–21; Jenkins & White, 1976, pp. 27–8.

- ^ "XII. A method of examining refractive and dispersive powers, by prismatic reflection". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 92: 365–380. 1802. doi:10.1098/rstl.1802.0014. S2CID 110328209.

- HELLA GmbH & Co. KGaA, "Rain sensor & headlight sensor testing – Repair instructions & fault diagnosis", accessed 9 April 2019; archived 8 April 2019.

- J. Gourlay, "Making Light Work – Light Sources for Modern Lighting Requirements", LED Professional, accessed 29 March 2019; archived 12 April 2016.

- D. Axelrod (April 1981), "Cell-substrate contacts illuminated by total internal reflection fluorescence", Journal of Cell Biology, 89 (1): 141–5, doi:10.1083/jcb.89.1.141, PMC 2111781, PMID 7014571.

- D. Axelrod (November 2001), "Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy in Cell Biology" (PDF), Traffic, 2 (11): 764–74, doi:10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21104.x, hdl:2027.42/72779, PMID 11733042, S2CID 15202097.

- Hecht, 2017, p. 138.

- R.W. Astheimer; G. Falbel; S. Minkowitz (January 1966), "Infrared modulation by means of frustrated total internal reflection", Applied Optics, 5 (1): 87–91, Bibcode:1966ApOpt...5...87A, doi:10.1364/AO.5.000087, PMID 20048791.

- N.J. Harrick (1962-3), "Fingerprinting via total internal reflection", Philips Technical Review, 24 (9): 271–4; archived January 2024

- Noldus Information Technology, "CatWalk™ XT", accessed 29 March 2019; archived 25 March 2019.

- E. Bruce, R. Bendure, S. Krein, and N. Lighthizer, "Zoom in on Gonioscopy", Review of Optometry, 21 September 2016.

- Glaucoma Associates of Texas, "Gonioscopy", accessed 29 March 2019; archived 22 August 2018.

- Boyer, 1959, p. 110.

- Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī, Tanqih al-Manazir (autograph manuscript, 708 AH / 1309 CE), Adilnor Collection.

- Boyer, 1959, pp. 113, 114, 335. Boyer cites J. Würschmidt's edition of Theodoric's De iride et radialibus impressionibus, in Beiträge zur Geschichte der Philosophie des Mittelalters, vol. 12, nos. 5–6 (1914), at p. 47.

- Boyer, 1959, pp. 307, 335.

- E. Mach (tr. J.S. Anderson & A.F.A. Young), The Principles of Physical Optics: An Historical and Philosophical Treatment (London: Methuen & Co, 1926), reprinted Mineola, NY: Dover, 2003, pp. 30–32.

- A.I. Sabra, Theories of Light: From Descartes to Newton (London: Oldbourne Book Co., 1967), reprinted Cambridge University Press, 1981, pp. 111–12.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, p. 39.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, pp. 40–41. Notice that Huygens' definition of the "angle of incidence" is the complement of the modern definition.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, pp. 39–40.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, pp. 40–41.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, pp. 16, 42.

- Huygens, 1690, tr. Thompson, pp. 92–94.

- Newton, 1730, p. 362.

- Darrigol, 2012, pp. 93–94, 103.

- Newton, 1730, pp. 370–371.

- Newton, 1730, p. 246. Notice that a "sine" meant the length of a side for a specified "radius" (hypotenuse), whereas nowadays we take the radius as unity or express the sine as a ratio.

- Newton, 1730, pp. 56–62, 264.

- Newton, 1730, pp. 371–372.

- Newton, 1730, p. 281.

- Newton, 1730, p. 373.

- Newton, 1730, p. 356.

- Buchwald, 1980, pp. 327, 331–332.

- Buchwald, 1980, pp. 335–336, 364; Buchwald, 1989, pp. 9–10, 13.

- Buchwald, 1989, pp. 19–21.

- Buchwald, 1989, p. 28.

- Darrigol, 2012, pp. 187–188.

- Buchwald, 1989, p. 30.

- Buchwald, 1980, pp. 29–31.

- E. Frankel (May 1976), "Corpuscular optics and the wave theory of light: The science and politics of a revolution in physics", Social Studies of Science, 6 (2): 141–84, at p. 145.

- Buchwald, 1989, p. 30 (quoting Malus).

- Darrigol, 2012, pp. 193–196, 290.

- Darrigol, 2012, p. 206.

- This effect had been previously discovered by Brewster, but not yet adequately reported. See: "On a new species of moveable polarization", [Quarterly] Journal of Science and the Arts, vol. 2, no. 3, 1817, p. 213; T. Young, "Chromatics", Supplement to the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (first half, issued February 1818), pp. 141–63, at p. 157; Lloyd, 1834, p. 368.

- Darrigol, 2012, p. 207.

- A. Fresnel, "Mémoire sur les modifications que la réflexion imprime à la lumière polarisée" ("Memoir on the modifications that reflection impresses on polarized light"), signed & submitted 10 November 1817, read 24 November 1817; printed in Fresnel, 1866, pp. 441–85, including pp. 452 (rediscovery of depolarization by total internal reflection), 455 (two reflections, "coupled prisms", "parallelepiped in glass"), 467–8 (phase difference per reflection); see also p. 487, note 1, for the date of reading.

- Darrigol, 2012, p. 212.

- Buchwald, 1989, pp. 390–391; Fresnel, 1866, pp. 646–648.

- A. Fresnel, "Note sur le calcul des teintes que la polarisation développe dans les lames cristallisées" et seq., Annales de Chimie et de Physique, Ser. 2, vol. 17, pp. 102–11 (May 1821), 167–96 (June 1821), 312–15 ("Postscript", July 1821); reprinted in Fresnel, 1866, pp. 609–48; translated as "On the calculation of the tints that polarization develops in crystalline plates, & postscript", Zenodo: 4058004, 2021.

- ^ A. Fresnel, "Mémoire sur la loi des modifications que la réflexion imprime à la lumière polarisée" ("Memoir on the law of the modifications that reflection impresses on polarized light"), read 7 January 1823; reprinted in Fresnel, 1866, pp. 767–99 (full text, published 1831), pp. 753–62 (extract, published 1823). See especially pp. 773 (sine law), 757 (tangent law), 760–61 and 792–6 (angles of total internal reflection for given phase differences).

- Buchwald, 1989, pp. 391–393; Darrigol, 2012, pp. 212–313; Whittaker, 1910, pp. 133–135.

- A. Fresnel, "Mémoire sur la double réfraction que les rayons lumineux éprouvent en traversant les aiguilles de cristal de roche suivant les directions parallèles à l'axe", read 9 December 1822; printed in Fresnel, 1866, pp. 731–51 (full text), pp. 719–29 (extrait, first published in Bulletin de la Société philomathique for 1822, pp. 191–8); full text translated as "Memoir on the double refraction that light rays undergo in traversing the needles of quartz in the directions parallel to the axis", Zenodo: 4745976, 2021.

- Buchwald, 1989, pp. 230–231; Fresnel, 1866, p. 744.

- Lloyd, 1834, pp. 369–370; Buchwald, 1989, pp. 393–394, 453; Fresnel, 1866, pp. 781–796.

- Fresnel, 1866, pp. 760–761, 792–796; Whewell, 1857, p. 359.

- Fresnel, 1866, pp. 760–761, 792–793.

- Fresnel, 1866, pp. 761, 793–796; Whewell, 1857, p. 359.

- Bochner, 1963, pp. 198–200.

- Whittaker, 1910, pp. 177–9.

- Bochner, 1963, p. 200; Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 613.

- Merriam-Webster, Inc., "critical angle", accessed 21 April 2019. (No primary source is given.)

- R.P. Feynman, 1985 (seventh printing, 1988), QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Princeton University Press, esp. pp. 33, 109–10.

Bibliography

- S. Bochner (June 1963), "The significance of some basic mathematical conceptions for physics", Isis, 54 (2): 179–205; JSTOR 228537.

- M. Born and E. Wolf, 1970, Principles of Optics, 4th Ed., Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- C.B. Boyer, 1959, The Rainbow: From Myth to Mathematics, New York: Thomas Yoseloff.

- J.Z. Buchwald (December 1980), "Experimental investigations of double refraction from Huygens to Malus", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 21 (4): 311–373.

- J.Z. Buchwald, 1989, The Rise of the Wave Theory of Light: Optical Theory and Experiment in the Early Nineteenth Century, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-07886-8.

- O. Darrigol, 2012, A History of Optics: From Greek Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-964437-7.

- R. Fitzpatrick, 2013, Oscillations and Waves: An Introduction, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4665-6608-8.

- R. Fitzpatrick, 2013a, "Total Internal Reflection", University of Texas at Austin, accessed 14 March 2018.

- A. Fresnel, 1866 (ed. H. de Senarmont, E. Verdet, and L. Fresnel), Oeuvres complètes d'Augustin Fresnel, Paris: Imprimerie Impériale (3 vols., 1866–70), vol. 1 (1866).

- E. Hecht, 2017, Optics, 5th Ed., Pearson Education, ISBN 978-1-292-09693-3.

- C. Huygens, 1690, Traité de la Lumière (Leiden: Van der Aa), translated by S.P. Thompson as Treatise on Light, University of Chicago Press, 1912; Project Gutenberg, 2005. (Cited page numbers match the 1912 edition and the Gutenberg HTML edition.)

- F.A. Jenkins and H.E. White, 1976, Fundamentals of Optics, 4th Ed., New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-032330-5.

- T.H. Levitt, 2013, A Short Bright Flash: Augustin Fresnel and the Birth of the Modern Lighthouse, New York: W.W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-35089-0.

- H. Lloyd, 1834, "Report on the progress and present state of physical optics", Report of the Fourth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (held at Edinburgh in 1834), London: J. Murray, 1835, pp. 295–413.

- I. Newton, 1730, Opticks: or, a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections, and Colours of Light, 4th Ed. (London: William Innys, 1730; Project Gutenberg, 2010); republished with foreword by A. Einstein and Introduction by E.T. Whittaker (London: George Bell & Sons, 1931); reprinted with additional Preface by I.B. Cohen and Analytical Table of Contents by D.H.D. Roller, Mineola, NY: Dover, 1952, 1979 (with revised preface), 2012. (Cited page numbers match the Gutenberg HTML edition and the Dover editions.)

- H.G.J. Rutten and M.A.M. van Venrooij, 1988 (fifth printing, 2002), Telescope Optics: A Comprehensive Manual for Amateur Astronomers, Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, ISBN 978-0-943396-18-7.

- J.A. Stratton, 1941, Electromagnetic Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill.

- W. Whewell, 1857, History of the Inductive Sciences: From the Earliest to the Present Time, 3rd Ed., London: J.W. Parker & Son, vol. 2.

- E. T. Whittaker, 1910, [https://archive.org/details/historyoftheorie00whitrich A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity: From the Age of Descartes to the Close of the Nineteenth Century, London: Longmans, Green, & Co.

External links

- Mr. Mangiacapre, "Fluorescence in a Liquid" (video, 1m28s), uploaded 13 March 2012. (Fluorescence and TIR of a violet laser beam in quinine water.)

- PhysicsatUVM, "Frustrated Total Internal Reflection" (video, 37s), uploaded 21 November 2011. ("A laser beam undergoes total internal reflection in a fogged piece of plexiglass...")