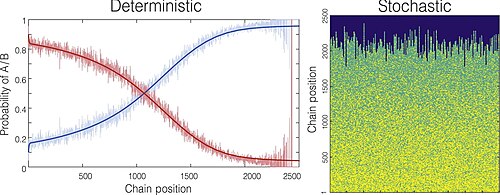

In polymer chemistry, gradient copolymers are copolymers in which the change in monomer composition is gradual from predominantly one species to predominantly the other, unlike with block copolymers, which have an abrupt change in composition, and random copolymers, which have no continuous change in composition (see Figure 1). In the gradient copolymer, as a result of the gradual compositional change along the length of the polymer chain less intrachain and interchain repulsion are observed.

The development of controlled radical polymerization as a synthetic methodology in the 1990s allowed for increased study of the concepts and properties of gradient copolymers because the synthesis of this group of novel polymers was now straightforward.

Due to the similar properties of gradient copolymers to that of block copolymers, they have been considered as a cost-effective alternative in applications for other preexisting copolymers.

Polymer Composition

In the gradient copolymer, there is a continuous change in monomer composition along the polymer chain (see Figure 2). This change in composition can be depicted in a mathematical expression. The local composition gradient fraction is described by molar fraction of monomer 1 in the copolymer and degree of polymerization and its relationship is as follows:

The above equation supposes all of the local monomer composition is continuous. To make up for this assumption, another equation of ensemble average is used:

The refers ensemble average of the local chain composition, refers degree of polymerization, refers number of polymer chains in the sample and refers composition of polymer chain i at position .

This second equation identifies the average composition over all present polymer chains at a given position, .

Synthesis

Prior to the development of controlled radical polymerization (CRP), gradient copolymers (as distinguished from statistical copolymers) were not synthetically possible. While a "gradient" can be achieved through compositional drift due to a difference in reactivity of the two monomers, this drift will not encompass the entire possible compositional range. All of the common CRP methods including atom transfer radical polymerization and Reversible addition−fragmentation chain transfer polymerization as well as other living polymerization techniques including anionic addition polymerization and ring-opening polymerization have been used to synthesize gradient copolymers.

The gradient can be formed through either a spontaneous or a forced gradient. Spontaneous gradient polymerization is due to a difference in reactivity of the monomers. The resulting change in composition throughout the polymerization creates an inconsistent gradient along the polymer. Forced gradient polymerization involves varying the comonomer composition of the feed being throughout the reaction time. Because the rate of addition of the second monomer influences the polymerization and therefore properties of the formed polymer, continuous information about the polymer composition is vital. The online compositional information is often gathered through automatic continuous online monitoring of polymerization reactions, a process which provides in situ information allowing for constant composition adjustment to achieve the desired gradient composition.

Properties

The wide range of composition possible in a gradient polymer due to the variety of monomers incorporated and the change of the composition results in a large variety of properties. In general, the glass transition temperature (Tg) is broad in comparison with the homopolymers. Micelles of the gradient copolymer can form when the gradient copolymer concentration is too high in a block copolymer solution. As the micelles form, the micelle diameter actually shrinks creating a "reel in" effect. Contrast matching SANS experiments revealed that the outer part of the core of the gradient copolymer micelles has a distinctly higher density than the middle of the core. This finding was attributed to back-folding of chains resulting from hydrophilic-hydrophobic interactions, leading to a new type of micelles that was referred to as micelles with a "bitterball-core" structure.

The composition can be determined by gel permeation chromatography(GPC) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Generally the composition has a narrow polydispersity index (PDI) and the molecular weight increases with time as the polymer forms.

Applications

Compatibilizing phase-separated polymer blends

For the compatiabilization of immiscible blends, the gradient copolymer can be used by improving mechanical and optical properties of immiscible polymers and decreasing its dispersed phase to droplet size. The compatibilization has been tested by reduction in interfacial tension and steric hindrance against coalescence. This application is not available for block and graft copolymer because of its very low critical micelle concentration (cmc). However, the gradient copolymer, which has higher cmc and exhibits a broader interfacial coverage, can be applied to effective blend compatibilizers.

A small amount of gradient copolymer (i.e.styrene/4-hydroxystyrene) is added to a polymer blend (i.e. polystyrene/polycaprolactone) during melt processing. The resulting interfacial copolymer helps to stabilize the dispersed phase due to the hydrogen-bonding effects of hydroxylstyrene with the polycaprolactone ester group.

Impact modifiers and sound or vibration dampers

The gradient copolymer have very broad glass transition temperature (Tg) in comparison with other copolymers, at least four times bigger than that of a random copolymer. This broad glass transition is one of the important features for vibration and acoustic damping applications. The broad Tg gives wide range of mechanical properties of material. The glass transition breadth can be adjusted by selection of monomers with different degrees of reactivity in their controlled radical polymerization (CRP). The strongly segregated styrene/4-hydroxystyrene (S/HS) gradient copolymer is used to study damping properties due to its unusual broad glass transition breadth.

Potential applications

There are many possible applications for gradient copolymer like pressure-sensitive adhesives, wetting agent, coating, or dispersion. However, these applications are not proved about its practical performance and stability as gradient copolymers. Recent studies have evaluated gradient copolymers as potential drug delivery carriers. Additionally, gradient copolymers have been shown the best F MRI signal-to-noise ratio in comparison with the analogue block copolymer structures, making them most promising as F MRI contrast agents.

See also

References

- Kryszewski, M (1998). "Gradient Polymers and Copolymers". Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 9 (4): 224–259. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1581(199804)9:4<244::AID-PAT748>3.0.CO;2-J. ISSN 1042-7147.

- Muzammil, Iqbal; Li, Yupeng; Lei, Mingkai (2017). "Tunable wettability and pH-responsiveness of plasma copolymers of acrylic acid and octafluorocyclobutane". Plasma Processes and Polymers. 14 (10): 1700053. doi:10.1002/ppap.201700053. S2CID 104161308.

- Beginn, Uwe (2008). "Gradient Copolymer". Colloid Polym Sci. 286 (13): 1465–1474. doi:10.1007/s00396-008-1922-y. S2CID 189866561.

- Matyjaszewski, Krzyszytof; Michael J. Ziegler; Stephen V. Arehart; Dorota Greszta; Tadeusz Pakula (2000). "Gradient Copolymers by Atom Transfer Radical Copolymerization". J. Phys. Org. Chem. 13 (12): 775–786. doi:10.1002/1099-1395(200012)13:12<775::aid-poc314>3.0.co;2-d.

- Cowie, J.M.G.; Valeria Arrighi (2008). Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials (Third ed.). CRC Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 9780849398131.

- ^ Mok, Michelle; Jungki Kim; John M. Torkelson (2008). "Gradient Copolymers with Broad Glass Transition Temperature Regions: Design of Purely Interphase Compositions for Damping Applications". Journal of Polymer Science. 46 (1): 48–58. Bibcode:2008JPoSB..46...48M. doi:10.1002/polb.21341.

- Kryven, Ivan; Zhao, Yutian R.; McAuley, Kimberley B.; Iedema, Piet (2018). "A deterministic model for positional gradients in copolymers". Chemical Engineering Science. 177: 491–500. Bibcode:2018ChEnS.177..491K. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2017.12.017. hdl:11245.1/e6aa0c74-10cd-4d83-87d3-5c7bfe315364. ISSN 0009-2509.

- Davis, Kelly; Krzysztof Matyjaszewski (2002). Statistical, Gradient, Block, and Graft Copolymers by Controlled/Living Radical Polymerizations. Advances in Polymer Science. Vol. 159. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1007/3-540-45806-9_1. ISBN 978-3-540-43244-9.

- Filippov, Sergey K.; Verbraeken, Bart; Konarev, Petr V.; Svergun, Dmitri I.; Angelov, Borislav; Vishnevetskaya, Natalya S.; Papadakis, Christine M.; Rogers, Sarah; Radulescu, Aurel; Courtin, Tim; Martins, José C.; Starovoytova, Larisa; Hruby, Martin; Stepanek, Petr; Kravchenko, Vitaly S. (2017). "Block and Gradient Copoly(2-oxazoline) Micelles: Strikingly Different on the Inside". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 8 (16): 3800–3804. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b01588.

- Ramic, Anthony J.; Julia C. Stehlin; Steven D. Hudson; Alexander M. Jamieson; Ica Manas-Zloczower (2000). "Influence of Block Copolymer on Droplet Brekup and Coalescence in Model Immiscible Polymer Blends". Macromolecules. 33 (2): 371–374. Bibcode:2000MaMol..33..371R. doi:10.1021/ma990420c.

- Kim, Jungki; Maisha K. Gray; Hongying Zhou; SonBinh T. Nguyen; John M. Torkelson (Feb 22, 2005). "Polymer Blend Compatibilization by Gradient Copolymer Addition during Melt Processing: Stabilization nof Dispersed Phase to Static Coarsening". Macromolecules. 38 (4): 1037–1040. Bibcode:2005MaMol..38.1037K. doi:10.1021/ma047549t.

- Muzammil, Iqbal; Li, Yupeng; Lei, Mingkai (2017). "Tunable wettability and pH-responsiveness of plasma copolymers of acrylic acid and octafluorocyclobutane". Plasma Processes and Polymers. 14 (10): 1700053. doi:10.1002/ppap.201700053. S2CID 104161308.

- Sedlacek, Ondrej; Bardoula, Valentin; Vuorimaa-Laukkanen, Elina; Gedda, Lars; Edwards, Katarina; Radulescu, Aurel; Mun, Grigoriy A.; Guo, Yong; Zhou, Junnian; Zhang, Hongbo; Nardello-Rataj, Véronique; Filippov, Sergey K.; Hoogenboom, Richard (2022). "Influence of Chain Length of Gradient and Block Copoly(2-oxazoline)s on Self-Assembly and Drug Encapsulation". Small. 18 (17): 2106251. doi:10.1002/smll.202106251. ISSN 1613-6829.

- Kaberov, Leonid I.; Kaberova, Zhansaya; Murmiliuk, Anastasiia; Trousil, Jiří; Sedláček, Ondřej; Konefal, Rafal; Zhigunov, Alexander; Pavlova, Ewa; Vít, Martin; Jirák, Daniel; Hoogenboom, Richard; Filippov, Sergey K. (2021). "Fluorine-Containing Block and Gradient Copoly(2-oxazoline)s Based on 2-(3,3,3-Trifluoropropyl)-2-oxazoline: A Quest for the Optimal Self-Assembled Structure for 19F Imaging". Biomacromolecules. 22 (7): 2963–2975. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.1c00367.

External links

- http://torkelson.northwestern.edu/Research/GCP/gcp.html

- http://www.cmu.edu/maty/materials/index.html

is described by molar fraction of monomer 1 in the copolymer

is described by molar fraction of monomer 1 in the copolymer  and degree of polymerization

and degree of polymerization  and its relationship is as follows:

and its relationship is as follows:

refers

refers  refers degree of polymerization,

refers degree of polymerization,  refers number of polymer chains in the sample and

refers number of polymer chains in the sample and  refers composition of polymer chain i at position

refers composition of polymer chain i at position