48°47′03″N 87°25′20″W / 48.78417°N 87.42222°W / 48.78417; -87.42222

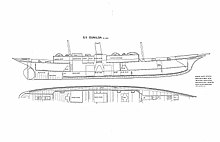

Gunilda before she sank Gunilda before she sank

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Gunilda |

| Namesake | Variant of Gunhild, an old Germanic feminine name meaning "war" |

| Owner |

|

| Port of registry |

|

| Identification | UK official number 104928 |

| Owner | William L. Harkness (1903-1911) |

| Operator | New York Yacht Club |

| Port of registry |

|

| Builder | Ramage & Ferguson, Leith, Scotland |

| Yard number | 149 |

| Launched | April 1, 1897 |

| In service | 1897 |

| Out of service | August 11, 1911 |

| Identification | US official number unknown |

| Fate | Sank off Rossport, Ontario |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Yacht |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 195 ft (59 m) |

| Beam | 24.7 ft (7.5 m) |

| Draft | 12 feet (3.7 m)/14.2 ft (4.3 m) |

| Installed power | 2 × 160 psi turbine boilers |

| Propulsion | Triple expansion steam engine |

| Speed | 14 knots (16 mph) |

Gunilda was a steel-hulled Scottish-built steam yacht in service between her construction in 1897 and her sinking in Lake Superior in 1911. Built in 1897 in Leith, Scotland by Ramage & Ferguson for J. M. or A. R. & J. M. Sladen, and became owned by F. W. Sykes in 1898; her first and second owners were all from England. In 1901, Gunilda was chartered by a member of the New York Yacht Club, sailing across the Atlantic Ocean with a complement of 25 crewmen. In 1903, she was purchased by oil baron William L. Harkness of Cleveland, Ohio, a member of the New York Yacht Club; she ended up becoming the club's flagship. Under Harkness' ownership, Gunilda visited many parts of the world, including the Caribbean, and beginning in 1910, the Great Lakes.

In the summer of 1911, Gunilda's owner, William L. Harkness, his family and friends were on an extended tour of northern Lake Superior. They were headed to Rossport, Ontario and then planned to head into Lake Nipigon to do some fishing for speckled trout. As she was about 5 miles (8.0 km) away from Rossport, Gunilda ran hard aground onto McGarvey Shoal on the north side of Copper Island. Most of the passengers were taken to Rossport. Harkness stayed behind to supervise the salvage, hiring the tug James Whalen and a barge to tow Gunilda off the shoal. On August 11, 1911, after she was pulled free, she suddenly rolled over to starboard, filled with water, and sank. Harkness and his family were picked up by James Whalen.

Her wreck was rediscovered in 1967 resting in 270 feet (82 m) of water, completely intact, with even the gilding on the hull surviving. Gunilda's wreck was the subject of multiple failed salvage attempts. In the late 1960s, Ed and Harold Flatt made multiple unsuccessful attempts to salvage her. Throughout the 1970s, Fred Broennle also made several unsuccessful attempts to raise Gunilda. In 1980, Jacques Cousteau and the Cousteau Society used the research vessel Calypso and the diving saucer SP-350 Denise to dive and film the wreck. The Cousteau Society called Gunilda the "best-preserved, most prestigious shipwreck in the world" and "the most beautiful shipwreck in the world".

History

Design and construction

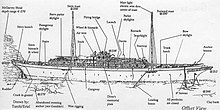

Gunilda (UK official number 104928) was built in 1897 by Ramage & Ferguson in Leith, Scotland. Her hull number was 149. She was designed by Joseph Edwin Wilkins, a naval architect who worked for Cox & King of Pall Mall, London, England. She cost about $200,000 to build. Her name is a variant of Gunhild, an old Germanic feminine name meaning "war". She was launched on April 1, 1897.

Her steel hull was 195 feet (59 m) long; one source states she had a length of 177 feet (54 m), another source states she had an overall length of 177.6 feet (54.1 m) and a below waterline length of 166.5 feet (50.7 m), her beam was 24.7 feet (7.5 m) (one source states 24.58 feet (7.49 m). Several sources state she had a draft of 12 feet (3.7 m), several other sources state her draft was 14.2 feet (4.3 m), and one source states she had a draft of 14.16 feet (4.32 m). She had a gross register tonnage of 385 and a net register tonnage of 158. She had a Thames Tonnage of 492 or 499 tons.

She was equipped by a triple expansion steam engine with pistons that had bores of 15 inches (38 cm), 24 inches (61 cm), and 37 inches (94 cm) and a stroke of 27 inches (69 cm). The engine was powered by steam produced by two 160 psi turbine boilers. Gunilda was driven by a single propeller and had a top speed of 14 knots (16 mph) (some sources state 12 knots (14 mph)).

Service history

Between 1897 and 1898 Gunilda was owned by either J. M. Sladen or by A. R. and J. M. Sladen; her home port was Wivenhoe in England. Her second owner was F. W. Sykes, who owned her between 1898 and 1903, during which time her home port was Leith. Her first and second owners were from England.

In 1901, Gunilda was chartered by a member of the New York Yacht Club of New York City, sailing over the Atlantic Ocean with 25 crewmen on board. American press reports at the time of her arrival described her as a schooner, rigged with 4,620 square feet (429 m) of canvas.

In 1903, Gunilda was purchased by oil baron William L. Harkness of Cleveland, Ohio. Harkness was a member of the New York Yacht Club. When he purchased Gunilda, she was officially registered in New York City and became the new flagship of the New York Yacht Club. In 1903, Gunilda's home port was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, however, in 1904, it became New York City. Under the ownership of Harkness, Gunilda visited several parts of the world, making multiple trips around the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean. In 1910, Harkness brought Gunilda to the Great Lakes to perform an extended cruise.

Final voyage

Gunilda stranded on McGarvey Shoal

Gunilda stranded on McGarvey Shoal

In 1911, William L. Harkness, his family and his friends were on an extended tour of the north shore of Lake Superior. In August 1911, the people on board had made plans to head into Lake Nipigon to fish for speckled trout. To sail into Lake Nipigon, Gunilda (manned by a crew of 20) needed to travel to Rossport, Ontario, then into Nipigon Bay, and finally through the Schreiber Channel. When Gunilda docked in Coldwell Harbor, Ontario, Harkness sought a pilot to guide them to Rossport and then into Nipigon Bay. Donald Murray, an experienced local man, offered his services for $15, but Harkness declined, claiming it was too much. The following day, Gunilda stopped in Jackfish Bay, Ontario to load coal. Harkness once again inquired about a pilot. Harry Legault offered to pilot Gunilda to Rossport for $25 plus a train fare back to Jackfish Bay. Gunilda's captain, Alexander Corkum, and his crew thought the offer was reasonable, but Harkness once again declined. As the US charts did not indicate that there were any shoals on their intended course, Harkness decided to proceed without a pilot with accurate knowledge of the region. As she was about 5 miles (8.0 km) off Rossport, Gunilda, travelling at full speed, ran hard aground on McGarvey Shoal (known locally as Old Man's Hump). Gunilda ran 85 feet (26 m) onto the shoal, raising her bow high out of the water.

After the grounding, Harkness and some his family and friends boarded one of Gunilda's motor launches and travelled to Rossport, catching a Canadian Pacific Railway train to Port Arthur, Ontario, where Harkness made arrangements for the Canadian Towing & Wrecking Company's tug James Whalen to be dispatched to free Gunilda. The next day, on August 11 (some sources state August 29, one source states August 31), James Whalen arrived with a barge in tow. The captain of James Whalen advised Harkness to hire a second tug and barge to properly stabilize Gunilda. Harkness once again refused. As Gunilda didn't have any towing bitts, a sling was slung around her and attached to James Whalen, and she pulled Gunilda directly astern. Gunilda's engines were reversed, but she remained on the shoal. They then tried to swing the stern back and forth, but this also failed. Wrecking master J. Wolvin of James Whalen decided to pull solely to starboard, as it was impossible to maneuver her stern to the port. Gunilda slid off the shoal, but as she slid into the water, she suddenly keeled over, and her masts hit the water. Water poured in through the portholes, doors, companionways, hatches, and skylights. Gunilda sank in a couple of minutes. As she sank, the crew of James Whalen cut the towline, fearing that Gunilda would pull her down as well. After Gunilda sank, the people who remained on her were picked up by James Whalen.

Lloyd's of London paid out a $100,000 insurance policy.

Gunilda wreck

This ship is very well-preserved, as can be seen from photographs taken by a dive team in 2022.

Gunilda today

The wreck of Gunilda was discovered in 1967 by Chuck Zender, who also made the first-ever dive to her. Her wreck rests on an even keel in 270 feet (82 m) of water to the lake bottom, and 242 feet (74 m) to her deck at the base of McGarvey Shoal. Her wreck is very intact, with everything that was on her when she sank still in place, including her entire superstructure, compass binnacle, and both of her masts. Numerous artefacts including a piano, several lanterns, and various pieces of furniture remain on board. Most of the paint on her hull survives, including the gilding. In 1980, Jacques Cousteau and the Cousteau Society used the research vessel Calypso and the diving saucer SP-350 Denise to dive and film the wreck. The Cousteau Society called Gunilda "the best-preserved, most prestigious shipwreck in the world" and "the most beautiful shipwreck in the world".

Two divers have died on the wreck of Gunilda. Charles "King" Hague died in 1970; his body was recovered in 1976. Reg Barrett from Burlington, Ontario died in 1989.

In 2019 a blogger on the Professional Association of Diving Instructors Tecrec blogsite named Gunilda the second-best technical diving site in the world, after the German battleship SMS Markgraf in Scapa Flow.

On June 10 2024, Viking Polaris conducted archaeological and tourism dives on the famous “Gunilda” shipwreck with their manned submersibles CS7.43 “Ringo” and CS7.44 “George”.

The first Archaeological reconnaissance dives were piloted by Ant Gilbert (Sub Operations Manager / Chief Pilot), with Archaeologist (Chris McEvoy) and Aaron Lawton (Head of Expedition Operations) onboard.

The dives were conducted as part of an Archaeological Impact Assessment together with guidelines highlighted by the province of Ontario. These marked the first manned submersibles dives since the Cousteau society filmed the wreck in 1980 with the SP-350 Denise.

Salvage attempts

Ed and Harold Flatt of Thunder Bay, Ontario launched the first salvage attempt on Gunilda. They used cranes and a barge to hook onto Gunilda's hull, managing to haul a piece of her mast up to the surface. They made another failed attempt in 1968, but a storm wrecked their barge and washed away most of their equipment.

In the 1970s, Fred Broennle made several attempts to raise Gunilda. In August 1970 Broennle and his dive partner, 23-year old Charles "King" Hague, dove Gunilda's wreck. On August 8, 1970 Broennle and Hague anchored over the wreck, but there were complications during the dive; Hague dove first, dying in the process. Broennle tried to rescue him but got decompression sickness.

In about 1973 or 1974 Broennle set up Deep Diving Systems to raise Gunilda's wreck, building several diving bells and purchasing several barges, cranes, and a Biomarine CCR 1000 rebreather. Several of his earlier dives were unsuccessful.

During the salvage efforts, Broennle recovered a brass grate from one of the skylights.

In April 1976 Broennle bought the wreck of Gunilda from Lloyd's of London on the condition that he could raise her. On July 13, 1976 while exploring the wreck with underwater cameras, Broennle located Hague's remains close to the wreck, near the port side of the stern, and recovered them sometime later. In September 1976 Broennle planned to dive Gunilda with his submersible Constructor, which cost Deep Diving Systems $1.5 million to design and build. Constructor bankrupted Broennle and Deep Diving Systems, ending their salvage efforts. In 1998, the story of Broennle's salvage efforts were made into a film, Drowning in Dreams.

References

- ^ Hanakova (2020).

- ^ Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library (2020).

- ^ Wrecksite (2012).

- Hofman (1970).

- MacTaggart (2001).

- ^ Grosjean (2008).

- ^ The Rebreather Site (2012).

- ^ Art Gallery of Ontario (2011).

- ^ Maki (1977).

- ^ McLean (2021).

- Bowling Green State University (2020).

- ^ Swayze (2001).

- ^ Info Superior (2017).

- ^ McWilliam (1996), p. 6.

- ^ Lynch (2019).

- ^ Rutledge Pics (2016).

- ^ Behrend (2018).

- ^ Great Lakes Underwater (2014).

- ^ Ricketts (2014).

- The Bay Adventures (2021).

- ^ McKay (1980).

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1911).

- National Park Service (2020).

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1937).

- “Century old sunken ship preserved in perfect condition beneath Lake Superior”, Caters News Agency (2022).

- Hagen (1980).

- ^ Peake (2015).

- ^ Save Ontario Shipwrecks (2018).

- Stitt (2013).

- ^ Lindsay (2010).

- TBNewsWatch (2019).

- Lonardi (2019).

- Global Underwater Explorers (2019).

- The Rebreather Site (2020).

- ^ Sumner (1999).

Sources

- Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library (2020). "Gunilda (1897, Yacht)". Alpena, Michigan: Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Art Gallery of Ontario (2011). "Marking the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the steam yacht Gunilda". Toronto, Ontario: Art Gallery of Ontario. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Behrend, Carl (2018). "Adventure Bound: A Father and Daughter Circumnavigate the Greatest Lake in the World". Minneapolis, Minnesota: Sailing Breezes. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Bowling Green State University (2020). "Gunilda". Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- The Bay Adventures (2021). "Gunilda". Nipigon, Ontario: By The Bay Adventures. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Global Underwater Explorers (2019). "Documenting The Gunilda". High Springs, Florida: Global Underwater Explorers. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Great Lakes Underwater (2014). "Diving the Gunilda". Kalamazoo, Michigan: J.R. Underhill Communications. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Grosjean, François (2008). "The 1913 Cox & King Catalogue of Yachts and Motor Boats". Neuchâtel, Switzerland: François Grosjean. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Hagen, Patricia (1980). "Cousteau: by land, sea and air". Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Michigan Daily. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Hanakova, Jitka (2020). "Luxury Yacht Gunilda". Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Shipwreck Explorers. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Hofman, E. (1970). The Steam Yachts: An Era of Elegance. Tuckahoe, New York: John de Graff.

- Info Superior (2017). "Gunilda, Great Lakes Deep Diving Pinnacle". Info Superior. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Lindsay, Dan (2010). "Gunilda". Brantford, Ontario: Sea - View Imaging. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Lonardi, Sandro (2019). "Technical Diving: The 10 Best Dive Sites in the World". Rancho Santa Margarita, California: Professional Association of Diving Instructors. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Lynch, Michael (2019). "Diving the Gunilda in Lake Superior". Michigan, United States: Michigan Diver. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- MacTaggart, R. (2001). The Golden Century: Classic Motor Yachts, 1830-1930. New York City, New York: W.W. Norton.

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1911). "Gunilda (yacht), sunk, 29 Aug 1911". Ontario, Canada: Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1937). "How Big Shot Took $1,000,000 Crack on the Chin". Ontario, Canada: Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- McKay, Shona (1980). "Time capsules beneath the Great Lakes". Toronto, Ontario: Maclean's. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- McLean, David (2021). Leith-built luxury vessel lies at bottom of Ontario lake in 'spectacular' condition. Edinburgh, Scotland: The Scotsman. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- McWilliam, Scott (1996). Gunilda Revisited – Report on the Gunilda Shipwreck. Brantford, Ontario: Academia.edu. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Maki, Allan (1977). "The lady in the lake — and the man who must have her". Toronto, Ontario: Maclean's. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- National Park Service (2020). "SS Chester A. Congdon: Wreck Event and Survivor Accounts". Washington D.C.: National Park Service. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Peake, Rob (2015). "Haunting video shows perfectly preserved wreck of classic steamship Gunilda". London, United Kingdom: Boat International Media. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Ricketts, Bruce (2014). "The Gunilda Shipwreck". Canada: Mysteries of Canada. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Rutledge Pics (2016). "Gunilda". Rutledge Pics. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018.

- Save Ontario Shipwrecks (2018). "Gunilda". Blenheim, Ontario: Save Ontario Shipwrecks. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Stitt, Scott (2013). "Civil Disobedience Wreck Diving". North Vancouver, British Columbia: Divermag. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Sumner, Luella (1999). "Drowning in Dreams". Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Swayze, David D. (2001). "Great Lakes Shipwrecks - G". Port Huron, Michigan: Boatnerd. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- TBNewsWatch (2019). "Underwater archeologists to document Lake Superior shipwrecks". Thunder Bay, Ontario: TBNewsWatch. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- The Rebreather Site (2020). "CCR 1000 by Biomarine". The Netherlands: The Rebreather Site. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- The Rebreather Site (2012). "Gunilda - Drowning in Dreams". The Netherlands: The Rebreather Site. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Wrecksite (2012). "SS Gunilda (+1911)". Affligem, Belgium: Wrecksite. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

External links

- Gunilda 2001, by Terry Irvine via YouTube

- Gunilda 2011 - 100 Years, by Terry Irvine via YouTube

- Gunilda 2016, by Richard Kurzel via YouTube

- Yacht Gunilda, by Liquid Productions

- Gunilda, by Superior Trips

- Gunilda - Great Lakes Shipwreck Photos, by Shipwreck Explorers

| Shipwrecks and maritime incidents in 1911 | |

|---|---|

| Shipwrecks |

|

| Other incidents |

|

| 1910 | |