| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: the article is full of duplicated informations in different sections. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

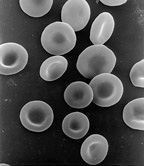

Hemorheology, also spelled haemorheology (haemo from Greek ‘αἷμα, haima 'blood'; and rheology, from Greek ῥέω rhéō, 'flow' and -λoγία, -logia 'study of'), or blood rheology, is the study of flow properties of blood and its elements of plasma and cells. Proper tissue perfusion can occur only when blood's rheological properties are within certain levels. Alterations of these properties play significant roles in disease processes. Blood viscosity is determined by plasma viscosity, hematocrit (volume fraction of red blood cell, which constitute 99.9% of the cellular elements) and mechanical properties of red blood cells. Red blood cells have unique mechanical behavior, which can be discussed under the terms erythrocyte deformability and erythrocyte aggregation. Because of that, blood behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid. As such, the viscosity of blood varies with shear rate. Blood becomes less viscous at high shear rates like those experienced with increased flow such as during exercise or in peak-systole. Therefore, blood is a shear-thinning fluid. Contrarily, blood viscosity increases when shear rate goes down with increased vessel diameters or with low flow, such as downstream from an obstruction or in diastole. Blood viscosity also increases with increases in red cell aggregability.

Blood viscosity

Blood viscosity is a measure of the resistance of blood to flow. It can also be described as the thickness and stickiness of blood. This biophysical property makes it a critical determinant of friction against the vessel walls, the rate of venous return, the work required for the heart to pump blood, and how much oxygen is transported to tissues and organs. These functions of the cardiovascular system are directly related to vascular resistance, preload, afterload, and perfusion, respectively.

The primary determinants of blood viscosity are hematocrit, red blood cell deformability, red blood cell aggregation, and plasma viscosity. Plasma's viscosity is determined by water-content and macromolecular components, so these factors that affect blood viscosity are the plasma protein concentration and types of proteins in the plasma. Nevertheless, hematocrit has the strongest impact on whole blood viscosity. One unit increase in hematocrit can cause up to a 4% increase in blood viscosity. This relationship becomes increasingly sensitive as hematocrit increases. When the hematocrit rises to 60 or 70%, which it often does in polycythemia, the blood viscosity can become as great as 10 times that of water, and its flow through blood vessels is greatly retarded because of increased resistance to flow. This will lead to decreased oxygen delivery. Other factors influencing blood viscosity include temperature, where an increase in temperature results in a decrease in viscosity. This is particularly important in hypothermia, where an increase in blood viscosity will cause problems with blood circulation.

Clinical significance

Many conventional cardiovascular risk factors have been independently linked to whole blood viscosity.

| Cardiovascular risk factors linked independently to whole blood viscosity |

|---|

| Hypertension |

| Total cholesterol |

| VLDL-cholesterol |

| LDL-cholesterol |

| HDL-cholesterol (negative correlation) |

| Triglycerides |

| Chylomicrons |

| Diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance |

| Metabolic syndrome |

| Obesity |

| Cigarette smoking |

| Male sex |

| Age |

Anemia can reduce blood viscosity, which may lead to heart failure. Furthermore, elevation of plasma viscosity correlates to the progression of coronary and peripheral artery diseases.

Normal level

In pascal-seconds (Pa·s), the viscosity of blood at 37 °C is normally 3 × 10 to 4 × 10, respectively 3 - 4 centipoise (cP) in the centimetre gram second system of units.

,

where is the density. Blood viscosity can be measured by viscometers capable of measurements at various shear rates, such as a rotational viscometer.

Blood viscoelasticity

Blood is a viscoelastic fluid, meaning that it possesses both viscous and fluid characteristics. The viscous component arises primarily through the viscosity of blood plasma, while the elastic component arises from deformation of the red blood cells. As the heart contracts, mechanical energy is transferred from the heart to the blood; a small part of the energy is dissipated by the viscosity of the suspension, another part is stored as elastic energy in the red blood cells, and the remaining energy is used to drive blood circulation and is thus converted to kinetic energy. Viscoelastic fluids make up a larger class of fluids called non-Newtonian fluids.

The red blood cells occupy about half of the volume of blood and possess elastic properties. This elastic property is the largest contributing factor to the viscoelastic behavior of blood. The large volume percentage of red blood cells at a normal hematocrit level leaves little room for cell motion and deformation without interacting with a neighboring cell. Calculations have shown that the maximum volume percentage of red blood cells without deformation is 58% which is in the range of normally occurring levels. Due to the limited space between red blood cells, it is obvious that in order for blood to flow, significant cell to cell interaction will play a key role. This interaction and tendency for cells to aggregate is a major contributor to the viscoelastic behavior of blood. Red blood cell deformation and aggregation is also coupled with flow-induced changes in the arrangement and orientation as a third major factor in its viscoelastic behavior. Other factors contributing to the viscoelastic properties of blood is the plasma viscosity, plasma composition, temperature, and the rate of flow or shear rate. Together, these factors make human blood viscoelastic, non-Newtonian, and thixotropic.

When the red cells are at rest or at very small shear rates, they tend to aggregate and stack together in an energetically favorable manner. The attraction is attributed to charged groups on the surface of cells and to the presence of fibrinogen and globulins. This aggregated configuration is an arrangement of cells with the least amount of deformation. With very low shear rates, the viscoelastic property of blood is dominated by the aggregation and cell deformability is relatively insignificant. As the shear rate increases the size of the aggregates begins to decrease. With a further increase in shear rate, the cells will rearrange and orient to provide channels for the plasma to pass through and for the cells to slide. In this low to medium shear rate range, the cells wiggle with respect to the neighboring cells allowing flow. The influence of aggregation properties on the viscoelasticity diminish and the influence of red cell deformability begins to increase. As shear rates become large, red blood cells will stretch or deform and align with the flow. Cell layers are formed, separated by plasma, and flow is now attributed to layers of cells sliding on layers of plasma. The cell layer allows for easier flow of blood and as such there is a reduced viscosity and reduced elasticity. The viscoelasticity of the blood is dominated by the deformability of the red blood cells.

Maxwell model

Maxwell Model concerns Maxwell fluids or Maxwell material. The material in Maxwell Model is a fluid which means it respects continuity properties for conservative equations : Fluids are a subset of the phases of matter and include liquids, gases, plasmas and, to some extent, plastic solids. Maxwell model is made to estimate local conservative values of viscoelasticity by a global measure in the integral volume of the model to be transposed to different flow situations. Blood is a complex material where different cells like red blood cells are discontinuous in plasma. Their size and shape are irregular too because they are not perfect spheres. Complicating moreover blood volume shape, red cells are not identically distributed in a blood sample volume because they migrate with velocity gradients in direction to the highest speed areas calling the famous representation of the Fåhræus–Lindqvist effect, aggregate or separate in sheath or plug flows described by Thurston. Typically, the Maxwell Model described below is uniformly considering the material (uniform blue color) as a perfect distributed particles fluid everywhere in the volume (in blue) but Thurston reveals that packs of red cells, plugs, are more present in the high speed region, if y is the height direction in the Maxwell model figure, (y~H) and there is a free cells layer in the lower speed area (y~0) what means the plasma fluid phase that deforms under Maxwell Model is strained following inner linings that completely escape from the analytical model by Maxwell.

In theory, a fluid in a Maxwell Model behaves exactly similarly in any other flow geometry like pipes, rotating cells or in rest state. But in practice, blood properties vary with the geometry and blood has shown being an inadequate material to be studied as a fluid in common sense. So Maxwell Model gives trends that have to be completed in real situation followed by Thurston model in a vessel regarding distribution of cells in sheath and plug flows.

If a small cubical volume of blood is considered, with forces being acted upon it by the heart pumping and shear forces from boundaries. The change in shape of the cube will have 2 components:

- Elastic deformation which is recoverable and is stored in the structure of the blood.

- Slippage which is associated with a continuous input of viscous energy.

When the force is removed, the cube would recover partially. The elastic deformation is reversed but the slippage is not. This explains why the elastic portion is only noticeable in unsteady flow. In steady flow, the slippage will continue to increase and the measurements of non time varying force will neglect the contributions of the elasticity.

Figure 1 can be used to calculate the following parameters necessary for the evaluation of blood when a force is exerted.

- Shear Stress:

- Shear Strain:

- Shear Rate:

A sinusoidal time varying flow is used to simulate the pulsation of a heart. A viscoelastic material subjected to a time varying flow will result in a phase variation between and represented by . If , the material is a purely elastic because the stress and strain are in phase, so that the response of one caused by the other is immediate. If = 90°, the material is a purely viscous because strain lags behind stress by 90 degrees. A viscoelastic material will be somewhere in between 0 and 90 degrees.

The sinusoidal time variation is proportional to . Therefore, the size and phase relation between the stress, strain, and shear rate are described using this relationship and a radian frequency, were is the frequency in Hertz.

- Shear Stress:

- Shear Strain:

- Shear Rate:

The components of the complex shear stress can be written as:

Where is the viscous stress and is the elastic stress. The complex coefficient of viscosity can be found by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress and the complex shear rate:

Similarly, the complex dynamic modulus G can be obtained by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress to the complex shear strain.

Relating the equations to common viscoelastic terms we get the storage modulus, G', and the loss modulus, G".

A viscoelastic Maxwell material model is commonly used to represent the viscoelastic properties of blood. It uses purely viscous damper and a purely elastic spring connected in series. Analysis of this model gives the complex viscosity in terms of the dashpot constant and the spring constant.

Oldroyd-B model

One of the most frequently used constitutive models for the viscoelasticity of blood is the Oldroyd-B model. There are several variations of the Oldroyd-B non-Newtonian model characterizing shear thinning behavior due to red blood cell aggregation and dispersion at low shear rate. Here we consider a three-dimensional Oldroyd-B model coupled with the momentum equation and the total stress tensor. A non Newtonian flow is used which insures that the viscosity of blood is a function of vessel diameter d and hematocrit h. In the Oldroyd-B model, the relation between the shear stress tensor B and the orientation stress tensor A is given by:

where D/Dt is the material derivative, V is the velocity of the fluid, C1, C2, g, are constants. S and B are defined as follows:

Viscoelasticity of red blood cells

Red blood cells are subjected to intense mechanical stimulation from both blood flow and vessel walls, and their rheological properties are important to their effectiveness in performing their biological functions in the microcirculation. Red blood cells by themselves have been shown to exhibit viscoelastic properties. There are several methods used to explore the mechanical properties of red blood cells such as:

- micropipette aspiration

- micro indentation

- optical tweezers

- high frequency electrical deformation tests

These methods worked to characterize the deformability of the red blood cell in terms of the shear, bending, area expansion moduli, and relaxation times. However, they were not able to explore the viscoelastic properties. Other techniques have been implemented such as photoacoustic measurements. This technique uses a single-pulse laser beam to generate a photoacoustic signal in tissues and the decay time for the signal is measured. According to the theory of linear viscoelasticity, the decay time is equal to the viscosity-elasticity ratio and therefore the viscoelasticity characteristics of the red blood cells could be obtained.

Another experimental technique used to evaluate viscoelasticity consisted of using Ferromagnetism beads bonded to a cells surface. Forces are then applied to the magnetic bead using optical magnetic twisting cytometry which allowed researchers to explore the time dependent responses of red blood cells.

is the mechanical torque per unit bead volume (units of stress) and is given by:

where H is the applied magnetic twisting field, is the angle of the bead’s magnetic moment relative to the original magnetization direction, and c is the bead constant which is found by experiments conducted by placing the bead in a fluid of known viscosity and applying a twisting field.

Complex Dynamic modulus G can be used to represent the relations between the oscillating stress and strain:

where is the storage modulus and is the loss modulus:

where and are the amplitudes of stress and strain and is the phase shift between them.

From the above relations, the components of the complex modulus are determined from a loop that is created by comparing the change in torque with the change in time which forms a loop when represented graphically. The limits of - d(t) loop and the area, A, bounded by the - d(t) loop, which represents the energy dissipation per cycle, are used in the calculations. The phase angle , storage modulus G', and loss modulus G then become:

where d is the displacement.

The hysteresis shown in figure 3 represents the viscoelasticity present in red blood cells. It is unclear if this is related to membrane molecular fluctuations or metabolic activity controlled by intracellular concentrations of ATP. Further research is needed to fully explore these interaction and to shed light on the underlying viscoelastic deformation characteristics of the red blood cells.

Effects of blood vessels

When looking at viscoelastic behavior of blood in vivo, it is necessary to also consider the effects of arteries, capillaries, and veins. The viscosity of blood has a primary influence on flow in the larger arteries, while the elasticity, which resides in the elastic deformability of red blood cells, has primary influence in the arterioles and the capillaries. Understanding wave propagation in arterial walls, local hemodynamics, and wall shear stress gradient is important in understanding the mechanisms of cardiovascular function. Arterial walls are anisotropic and heterogeneous, composed of layers with different bio-mechanical characteristics which makes understanding the mechanical influences that arteries contribute to blood flow very difficult.

Medical reasons for a better understanding

From a medical standpoint, the importance of studying the viscoelastic properties of blood becomes evident. With the development of cardiovascular prosthetic devices such as heart valves and blood pumps, the understanding of pulsating blood flow in complex geometries is required. A few specific examples are the effects of viscoelasticity of blood and its implications for the testing of a pulsatile Blood Pumps. Strong correlations between blood viscoelasticity and regional and global cerebral blood flow during cardiopulmonary bypass have been documented.

This has also led the way for developing a blood analog in order to study and test prosthetic devices. The classic analog of glycerin and water provides a good representation of viscosity and inertial effects but lacks the elastic properties of real blood. One such blood analog is an aqueous solution of Xanthan gum and glycerin developed to match both the viscous and elastic components of the complex viscosity of blood.

Normal red blood cells are deformable but many conditions, such as sickle cell disease, reduce their elasticity which makes them less deformable. Red blood cells with reduced deformability have increasing impedance to flow, leading to an increase in red blood cell aggregation and reduction in oxygen saturation which can lead to further complications. The presence of cells with diminished deformability, as is the case in sickle cell disease, tends to inhibit the formation of plasma layers and by measuring the viscoelasticity, the degree of inhibition can be quantified.

History

In early theoretical work, blood was treated as a non-Newtonian viscous fluid. Initial studies had evaluated blood during steady flow and later, using oscillating flow. Professor George B. Thurston, of the University of Texas, first presented the idea of blood being viscoelastic in 1972. The previous studies that looked at blood in steady flow showed negligible elastic properties because the elastic regime is stored in the blood during flow initiation and so its presence is hidden when a flow reaches steady state. The early studies used the properties found in steady flow to derive properties for unsteady flow situations. Advancements in medical procedures and devices required a better understanding of the mechanical properties of blood.

Constitutive equations

The relationships between shear stress and shear rate for blood must be determined experimentally and expressed by constitutive equations. Given the complex macro-rheological behavior of blood, it is not surprising that a single equation fails to completely describe the effects of various rheological variables (e.g., hematocrit, shear rate). Thus, several approaches to defining these equations exist, with some the result of curve-fitting experimental data and others based on a particular rheological model.

- Newtonian fluid model where has a constant viscosity at all shear rates. This approach is valid for high shear rates () where the vessel diameter is much bigger than the blood cells.

- Bingham fluid model takes into account the aggregation of red blood cells at low shear rates. Therefore, it acts as an elastic solid under threshold level of shear stress, known as yield stress.

- Einstein model where η0 is the suspending fluid Newtonian viscosity, "k" is a constant dependent on particle shape, and H is the volume fraction of the suspension occupied by particles. This equation is applicable for suspensions having a low volume fraction of particles. Einstein showed k=2.5 for spherical particles.

- Casson model where "a" and "b" are constants; at very low shear rates, b is the yield shear stress. However, for blood, the experimental data can not be fit over all shear rates with only one set of constants "a" and "b", whereas fairly good fit is possible by applying the equation over several shear rate ranges and thereby obtaining several sets of constants.

- Quemada model where k0, k∞ and γc are constants. This equation accurately fits blood data over a very wide range of shear rates.

Other characteristics

The Fåhraeus effect

Main article: Fåhræus effectThe finding that, for blood flowing steadily in tubes with diameters of less than 300 micrometres, the average hematocrit of the blood in the tube is less than the hematocrit of the blood in the reservoir feeding the tube is known as the Fåhræus effect. This effect is generated in the concentration entrance length of the tube, in which erythrocytes move towards the central region of the tube as they flow downstream. This entrance length is estimated to be about the distance that the blood travels in a quarter of a second for blood where red blood cell aggregation is negligible and the vessel diameter is greater than about 20 micrometres.

The Fåhræus–Lindqvist effect

Main article: Fåhræus–Lindqvist effectAs the characteristic dimension of a flow channel approaches the size of the particles in a suspension; one should expect that the simple continuum model of the suspension will fail to be applicable. Often, this limit of the applicability of the continuum model begins to manifest itself at characteristic channel dimensions that are about 30 times the particle diameter: in the case of blood with a characteristic RBC dimension of 8 μm, an apparent failure occurs at about 300 micrometres. This was demonstrated by Fåhraeus and Lindqvist, who found that the apparent viscosity of blood was a function of tube diameter for diameters of 300 micrometres and less when they flowed constant-hematocrit blood from a well-stirred reservoir through a tube. The finding that for small tubes with diameters below about 300 micrometres and for faster flow rates which do not allow appreciable erythrocyte aggregation, the effective viscosity of the blood depends on tube diameter is known as the Fåhræus–Lindqvist effect.

See also

- Alfred L. Copley

- Blood hammer

- Biorheology, the study of flow properties(rheology) of biological fluids.

- Hemodynamics

- Hyperviscosity syndrome

- Rouleaux, is a configuration that RBC aggregates take.

References

- ^ Baskurt, OK; Hardeman M; Rampling MW; Meiselman HJ (2007). Handbook of Hemorheology and Hemodynamics. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press. pp. 455. ISBN 978-1586037710. ISSN 0929-6743.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Baskurt OK, Meiselman HJ (2003). "Blood rheology and hemodynamics". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 29 (5): 435–450. doi:10.1055/s-2003-44551. PMID 14631543. S2CID 17873138.

- ^ Késmárky G, Kenyeres P, Rábai M, Tóth K (2008). "Plasma viscosity: a forgotten variable". Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 39 (1–4): 243–6. doi:10.3233/CH-2008-1088. PMID 18503132. Archived from the original on 2016-05-14.

- ^ Tefferi A (May 2003). "A contemporary approach to the diagnosis and management of polycythemia vera". Curr. Hematol. Rep. 2 (3): 237–41. PMID 12901345.

- Lenz C, Rebel A, Waschke KF, Koehler RC, Frietsch T (2008). "Blood viscosity modulates tissue perfusion: sometimes and somewhere". Transfus Altern Transfus Med. 9 (4): 265–272. doi:10.1111/j.1778-428X.2007.00080.x. PMC 2519874. PMID 19122878.

- Kwon O, Krishnamoorthy M, Cho YI, Sankovic JM, Banerjee RK (February 2008). "Effect of blood viscosity on oxygen transport in residual stenosed artery following angioplasty". Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 130 (1): 011003. doi:10.1115/1.2838029. PMID 18298179. S2CID 40266740.

- ^ Jeong, Seul-Ki; et al. (April 2010). "Cardiovascular risks of anemia correction with erythrocyte stimulating agents: should blood viscosity be monitored for risk assessment?". Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 24 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1007/s10557-010-6239-7. PMID 20514513. S2CID 6366788.

- Elert, Glenn (November 27, 2021). "Viscosity". The Physics Hypertextbook – via physics.info.

- Baskurt OK, Boynard M, Cokelet GC, et al. (2009). "New Guidelines for Hemorheological Laboratory Techniques". Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation. 42 (2): 75–97. doi:10.3233/CH-2009-1202. PMID 19433882. S2CID 15866651.

- A. Burton (1965). Physiology and Biophysics of Circulation. Chicago (USA): Year Book Medical Publisher Inc. p. 53.

- G. Thurston; Nancy M. Henderson (2006). "Effects of flow geometry on blood Viscoelasticity". Biorheology. 43 (6): 729–746. PMID 17148856.

- G. Thurston (1989). "Plasma Release – Cell Layering Theory for Blood Flow". Biorheology. 26 (2): 199–214. doi:10.3233/bir-1989-26208. PMID 2605328.

- G. Thurston (1979). "Rheological Parameters for the Viscosity, Viscoelasticity, and thixotropy of Blood". Biorheology. 16 (3): 149–162. doi:10.3233/bir-1979-16303. PMID 508925.

- L. Pirkl and T. Bodnar, Numerical Simulation of Blood Flow Using Generalized Oldrroyd-B Model, European Conference on Computational Fluid Dynamics, 2010

- ^ Thurston G., Henderson Nancy M. (2006). "Effects of flow geometry on blood Viscoelasticity". Biorheology. 43 (6): 729–746. PMID 17148856.

- T. How, Advances in Hemodynamics and Hemorheology Vol. 1, JAI Press LTD., 1996, 1-32.

- R. Bird, R. Armstrong, O. Hassager, Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids; Fluid Mechanic, 1987, 2, 493 - 496

- M. Mofrad, H. Karcher, and R. Kamm, Cytoskeletal mechanics: models and measurements, 2006, 71-83

- V. Lubarda and A. Marzani, Viscoelastic response of thin membranes with application to red blood cells, Acta Mechanica, 2009, 202, 1–16

- D. Fedosov, B. Caswell, and G. Karniadakis, Coarse-Grained Red Blood Cell Model with Accurate Mechanical Properties, Rheology and Dynamics, 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2009

- J. Li, Z. Tang, Y. Xia, Y. Lou, and G. Li, Cell viscoelastic characterization using photoacoustic measurement, Journal of Applied Physics, 2008, 104

- M. Marinkovic, K. Turner, J. Butler, J. Fredberg, and S. Suresh, Viscoelasticity of the Human Red Blood Cell, American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 2007, 293, 597-605.

- A. Ündar, W. Vaughn, and J. Calhoon, The effects of cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest on blood viscoelasticity and cerebral blood flow in a neonatal piglet model, Perfusion 2000, 15, 121–128

- S. Canic, J. Tambaca, G. Guidoboni, A. Mikelic, C Hartley, and D Rosenstrauch, Modeling Viscoelastic Behavior of Arterial Walls and their Interaction with Pulsatile Blood Flow, Journal of Applied Mathematics, 2006, 67, 164–193

- J. Long, A. Undar, K. Manning, and S. Deutsch, Viscoelasticity of Pediatric Blood and its Implications for the Testing of a Pulsatile Pediatric Blood Pump, American Society of Internal Organs, 2005, 563 - 566

- A. Undar and W. Vaughn, Effects of Mild Hypothermic Cardiopulmonary Bypass on Blood Viscoelasticity in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Patients, Artificial Organs 26(11), 964–966

- K. Brookshier and J. Tarbell, Evaluation of a transparent blood analog fluid: aqueous xanthan gum/glycerin, Biorheology, 1993, 2, 107-16

- G. Thurston, N. Henderson, and M. Jeng, Effects of Erythrocytapheresis Transfusion on the Viscoelasticity of Sickle Cell Blood, Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 30 (2004) 61–75

- J. Womersley, Method for Calculation of Velocity, Rate of Flow and Viscous Drag in Arteries when the Pressure Gradient is Known, Amer. Journal Physiol. 1955, 127, 553-563.

- G. Thurston, Viscoelasticity of human blood, Biophysical Journal, 1972, 12, 1205–1217.

- G. Thurston, The Viscosity and Viscoelasticity of Blood in Small Diameter Tubes, Microvascular Research, 1975, 11, 133-146.

- Fung, Y.C. (1993). Biomechanics: mechanical properties of living tissues (2. ed.). New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 9780387979472.

of blood at 37 °C is normally 3 × 10 to 4 × 10, respectively 3 - 4 centi

of blood at 37 °C is normally 3 × 10 to 4 × 10, respectively 3 - 4 centi

,

,

is the density. Blood viscosity can be measured by viscometers capable of measurements at various shear rates, such as a rotational

is the density. Blood viscosity can be measured by viscometers capable of measurements at various shear rates, such as a rotational

and

and  represented by

represented by  . If

. If  , the material is a purely elastic because the stress and strain are in phase, so that the response of one caused by the other is immediate. If

, the material is a purely elastic because the stress and strain are in phase, so that the response of one caused by the other is immediate. If  . Therefore, the size and phase relation between the stress, strain, and shear rate are described using this relationship and a radian frequency,

. Therefore, the size and phase relation between the stress, strain, and shear rate are described using this relationship and a radian frequency,  were

were  is the frequency in

is the frequency in

is the viscous stress and

is the viscous stress and  is the elastic stress.

The complex coefficient of viscosity

is the elastic stress.

The complex coefficient of viscosity  can be found by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress and the complex shear rate:

can be found by taking the ratio of the complex shear stress and the complex shear rate:

is a function of vessel diameter d and hematocrit h. In the Oldroyd-B model, the relation between the shear stress tensor B and the orientation stress tensor A is given by:

is a function of vessel diameter d and hematocrit h. In the Oldroyd-B model, the relation between the shear stress tensor B and the orientation stress tensor A is given by:

is the mechanical torque per unit bead volume (units of stress) and is given by:

is the mechanical torque per unit bead volume (units of stress) and is given by:

is the angle of the bead’s magnetic moment relative to the original magnetization direction, and c is the bead constant which is found by experiments conducted by placing the bead in a fluid of known viscosity and applying a twisting field.

is the angle of the bead’s magnetic moment relative to the original magnetization direction, and c is the bead constant which is found by experiments conducted by placing the bead in a fluid of known viscosity and applying a twisting field.

is the storage modulus and

is the storage modulus and  is the loss modulus:

is the loss modulus:

and

and  are the amplitudes of stress and strain and

are the amplitudes of stress and strain and

) where the vessel diameter is much bigger than the blood cells.

) where the vessel diameter is much bigger than the blood cells.