United States historic place

| Cove Fort | |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

Front View Front View | |

| |

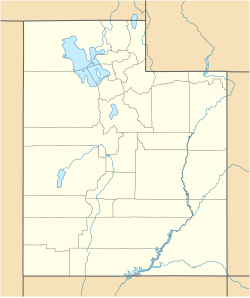

| Location | Millard County, Utah, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°36′06″N 112°34′49″W / 38.60167°N 112.58028°W / 38.60167; -112.58028 |

| Built | 1867 |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000623 |

Cove Fort is a fort, unincorporated community, and historical site located in Millard County, Utah. It was founded in 1867 by Ira Hinckley (the paternal grandfather of Gordon B. Hinckley) at the request of Brigham Young. One of its distinctive features is the use of volcanic rock in the construction of the walls, rather than the wood used in many mid-19th-century western forts. This difference in construction is the reason it is one of very few forts of this period still surviving.

Cove Fort is the closest named place to the western terminus of Interstate 70, resulting in Cove Fort being listed as a control city on freeway signs, though the fort itself is historical and has no permanent population.

History

The site for Cove Fort was selected by Brigham Young because of its location about halfway between Fillmore (formerly the capital of the Utah Territory) and the nearest city, Beaver. It provided a way station for people traveling the Mormon Road. A town would have been constructed at the Cove Fort site, but the water supply was inadequate to support a sizable population. Another key factor in the selection of the site was the prior existence of a wooden-palisade fort, Willden Fort, which provided shelter and safety for the work crews who constructed Cove Fort.

The fort is a square, 100 ft (30 m) on each side. The walls are constructed of black volcanic rock and dark limestone, both quarried from the nearby mountains. The walls are 18 ft high and 4 ft thick at the base, tapering to 2 ft thick at the top. The fort has two sets of large wooden doors at the east and west ends, originally filled with sand to stop arrows and bullets, and contains 12 interior rooms (six on the north wall and six on the south wall.)

As a daily stop for two stagecoach lines, as well as many other travelers, Cove Fort was heavily used for many years, often housing and feeding up to 75 people at a time. In addition to providing a place to rest, a blacksmith/farrier resided at the fort, who shod horses and oxen, and also repaired wagon wheels. With its telegraph office and as a Pony Express stop, it also acted as a regional communications hub.

Restoration

In the early 1890s, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints determined the fort was no longer required and leased it out to a number of parties, eventually selling it to W.H. Kesler in 1911. By 1903 when Kesler visited the Fort, a fire had destroy the north side rooms and parts were greatly deteriorated. The Keslers leased the Fort later that year and in the spring of 1904 moved into it with his wife Sarah to raise a their family and earn a living with cattle, horses, and cows. They slowly fixed up the fort, raised alfalfa, planted fruit trees, and rebuilt the north side rooms in 1917.

In 1988, the Hinckley family purchased the fort and donated it back to the Church. The Church restored the fort, transported Ira Hinckley's Coalville, Utah, cabin to the site, constructed a visitor center, and reopened the fort as a historic site. The site provides free guided tours daily, starting from about 8 am until one half-hour before sunset.

Transportation

See also: Interstate 70 in UtahThe first highway to traverse Cove Fort was the Arrowhead Trail, which connected Salt Lake City with Los Angeles. When the U.S. Highway system was formed, this route became U.S. Route 91, and is today Interstate 15. When the Interstate Highway System was in the planning stages, planners noted no direct connection existed between the central United States and southern California. The result to fill this gap was a new freeway that would be built west from Green River, Utah, towards Cove Fort, along a path that used to be inaccessible by paved roads. Since that time, Cove Fort has also served as the western terminus of Interstate 70.

In 2004, the Federal Highway Administration was testing a new typeface, Clearview, designed to have improved readability at night with headlight illumination. One test sign was placed at Baltimore, Maryland – the eastern terminus of Interstate 70 – that listed Cove Fort as a control city with a distance of 2,200 mi (3,500 km). One employee stated with the number of queries the department received about Cove Fort, the test was a success. The sign became so popular that after the test was over, federal authorities made arrangements with Maryland authorities to keep the sign permanently installed. The sign prompted a series of stories about Cove Fort to be published in the Baltimore area. Since that time, a small effort has been made by people in both states to lobby the Utah Department of Transportation to reciprocate by placing a sign at Cove Fort listing the distance to Baltimore.

See also

- Fort Deseret, another fort, also NRHP-listed

- Moyle House and Indian Tower, another fort, also NRHP-listed

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "What to Expect When You Visit the Cove Fort Historic Site". Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- "Cove Fort, Then and Now". history.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- "Why Does I-70 End in Cove Fort, Utah? - Ask the Rambler - General Highway History - Highway History - Federal Highway Administration". Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- Porter, Larry C. (1966). A Historical Analysis of Cove Fort, Utah. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University. p. 33.

- Porter, Larry C (1966). A Historical Analysis of Cove Fort, Utah. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University. pp. 19–23.

- Olmstead, Jacob. "Cove Fort, Then and Now". Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ "Cove Fort". history.churchofjesuschrist.org. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- https://issuu.com/utah10/docs/utah_historical_quarterly_volume90_2022_number2/s/15837906

- ^ Weingroff, Richard. "Ask the Rambler: Why Does I-70 End in Cove Fort, Utah?". U.S. Department of Transportation – Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Hiaasen, Rob (June 4, 2004). "Go West Young Man; Like Horace Greeley's Famed Advice, Curious Sign on I-70 Beckons Yonder". The Baltimore Sun.

Further reading

- Amazing But True Mormon Stories by Joan Oviatt

- "Cove Fort" article in the Utah History Encyclopedia (1994). The article was written by Larry Porter and the Encyclopedia was published by the University of Utah Press. ISBN 9780874804256. Archived from the original on March 21, 2024 and retrieved on April 18, 2024.

- Exceptional Stories from the Lives of Early Apostles by Leon R. Hartshorn

- Great Ghost Towns of the West by Tom Till and Teresa Jordan

- History of Millard County (Lesson for ... / Daughters of Utah Pioneers) by Lou Jean S Wiggins

- Mormon Architecture by Joseph Weston

- Mormon History by Ronald W. Walker, David J. Whittaker, and James B. Allen

- A New Zion: The Story of the Latter-day Saints by Bill Harris

- Nineteenth-Century Mormon Architecture and City Planning by C. Mark Hamilton

- The People: Indians of the American Southwest by Stephen Trimble

- Quilts and Women of the Mormon Migrations by Mary Bywater Cross

- Utah Byways: 65 of Utah's Best Backcountry Drives by Tony Huegel

- "LDS Restoration Project Gives Breath of New Life to Utah's Old Cove Fort" By Brian Giles, Feb. 6, 1992, Deseret News

- "Newly Restored Cove Fort Will Be Dedicated Saturday" By Reed L. Madsen, May 19, 1994, Deseret News

- "Visitors to Cove Fort think owl family's a hoot" By Reed L. Madsen, June 15, 1998, Deseret News

- "Cove Fort gets water boost" by Lynn Arave, July 20, 2002, Deseret News

- "Tools sought For Blacksmith Museum Exhibit" by Reed L. Madsen, April 4, 1993, Deseret News

- "Couple gets hitched — literally — on wagon trip" Sept. 16, 2001, Deseret News

- "Hinckley worked to remind and reconcile Mormons with their past" by Peggy Fletcher Stack, February 6, 2008, Salt Lake Tribune

External links

- Official web site of the Cove Fort Historic Site

- Unofficial Cove Fort Historical Site

- Old Cove Fort Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine from Utah.com

- Cove Fort at the Millard County tourism site.

- Utah Forts: Cove Fort at Legends of America historic site.

- Cove Fort at Great Basin National Heritage Route website.

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. UT-57, "Cove Fort, State Routes 4 & 161, Kanosh, Millard County, UT", 7 photos, 5 measured drawings, 6 data pages

- 1867 establishments in Utah Territory

- Buildings and structures in Millard County, Utah

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah

- Forts in Utah

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Utah

- Great Basin National Heritage Area

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Utah

- History museums in Utah

- Landmarks in Utah

- Museums in Millard County, Utah

- National Register of Historic Places in Millard County, Utah

- Open-air museums in Utah

- Pony Express stations

- Pre-statehood history of Utah

- Properties of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Unincorporated communities in Millard County, Utah

- Utah Territory

- Waystations