Location of Japan (dark green) Location of Japan (dark green) | |

| Medicinal | Illegal |

|---|---|

| Recreational | Illegal |

| Hemp | Legal |

Cannabis has been cultivated in Japan since the Jōmon period of Japanese prehistory approximately six to ten thousand years ago. As one of the earliest cultivated plants in Japan, cannabis hemp was an important source of plant fiber used to produce clothing, cordage, and items for Shinto rituals, among numerous other uses. Hemp remained ubiquitous for its fabric and as a foodstuff for much of Japanese history, before cotton emerged as the country's primary fiber crop amid industrialization during the Meiji period. Following the conclusion of the Second World War and subsequent occupation of Japan, a prohibition on cannabis possession and production was enacted with the passing of the Cannabis Control Law.

As of 2024, the possession of cannabis for recreational and medicinal use is illegal in Japan, though a law legalizing medical cannabis was passed by the House of Councillors in late 2023. The cultivation of commercial cannabis hemp is permitted under a strictly regulated licensing system. While other East Asian and industrialized nations have generally moved to relax laws that criminalize cannabis in recent decades, Japan has maintained and strengthened laws that prohibit the use, possession, and cultivation of cannabis. The proportion of the Japanese population that has used cannabis at least once was 1.8 percent in 2019, making it the second most popular illicit drug in the country behind methamphetamine.

History

Prehistoric and ancient Japan

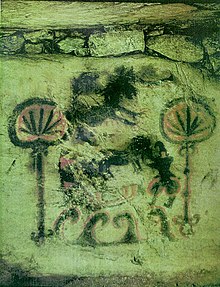

Though it is possible that cannabis is native to the Japanese archipelago, it most likely spread to what is now modern Japan from Korea and China; the common term for "hemp" in Japanese is taima (大麻), derived from the Chinese dà má. Cannabis was likely introduced roughly 18,000 years ago via a land bridge that connected the Asian continent to the Japanese archipelago. Cultivation of cannabis began during the Jōmon period at least 6,000 to 7,000 years ago and possibly as early as 10,000 years ago, making cannabis one of the earliest cultivated plants in Japan. The plant was grown as a food source and for its fibers, which were used to create clothing, rope, nets, and later washi (paper). Owing to the plant's association with purity, cannabis hemp fibers were also used by Shinto priests for ritual cleansing and to exorcise evil spirits, a practice that continues to the present day. Artifacts made from hemp have been recovered from the Torihama shell mound, an early Jōmon settlement.

Hemp production continued into the Yayoi period, with Chinese historian Chen Shou noting in his Records of the Three Kingdoms that the Japanese cultivated hemp along with rice and mulberry; Shou's claims are supported by the recovery of hemp cloth from the Yayoi cemetery at the Yoshinogari site in Kyushu. The growth of the Yayoi population combined with the introduction of loom weaving from the Asian continent led to an increased need for weaving fiber, and subsequently an expansion of hemp cultivation. By the 3rd century, hemp clothing was widely available in Japan. The indigenous Ainu of Hokkaido may have also used hemp fiber for cordage and as weaving for clothing, though it was not used in their shamanic rituals.

It is unclear how extensively cannabis was used for its psychoactive properties during this period. There is circumstantial evidence that cannabis resin may have been ingested for ritualistic or shamanic purposes: shamanism was central to Jōmon culture, and the mind-altering properties of cannabis were used for divination and communication with deceased ancestors in China as recently as the third millennium BCE. Regardless, any ritualistic use of cannabis for psychoactive purposes was suppressed in Japan following the arrival of Confucianism in the 3rd century.

Classical and feudal Japan

Cannabis use and production continued as Japan unified under a centralized government. References to cannabis appear in Man'yōshū, the oldest extant collection of Japanese waka (poetry), and in haiku poetry; bundles of cannabis were also traditionally burned during Bon to welcome the spirits of the deceased. By 645 CE, hemp was among the goods taxed by the ruling Yamato court, which also paid corvée laborers in hemp cloth and other items collected from commoners as exemption revenue. The ascendance of the feudal daimyo led to the further cultivation of commodity crops like hemp, which provided them an additional source of revenue through both sale and taxation. While the wealthy classes typically wore silk clothing during this period, hemp was the main fiber used to make clothing among commoners; hemp was also used to make uniforms and leisure kimono for samurai, training clothes for martial arts, and military uniforms. As Japan pursued a policy of economic isolationism during the Edo period, agricultural plots in the south of the country were used to grow cotton, which was highly valued at the time, while hemp was grown on a smaller and more irregular scale in the north.

As in the prehistoric and ancient periods, it is unclear how extensively cannabis was used for its psychoactive properties during this time. Historians have speculated that the wide availability of cannabis may have made it the intoxicant of choice for commoners, contrasting the monopolization of sake extracted from rice by the upper classes.

Early modern and post-war Japan

As a result of higher agricultural yields prompted by industrialization during the Meiji period, cotton came to gradually replace hemp as Japan's primary fiber crop. Though cotton clothing became readily available among the urban working class, hemp clothing remained common among the rural peasantry, who would often combine hemp fabric and cotton rags to create patchwork garments. Contemporaneously, specialized fine hemp clothing produced using modern weaving techniques began to emerge, though the high labor costs associated with creating these garments meant they were purchased and worn exclusively by the wealthy. By the end of the twentieth century, cotton clothing had become ubiquitous in Japan across economic classes, while only the upper classes continued to wear traditional fine hemp clothing – a reversal from hemp's previous role as the fabric of commoners.

By the early 20th century, cannabis-based cures for insomnia and muscle pain could be purchased in Japanese drug stores. Its ritual use also continued, with early 20th century American historian George Foot Moore observing that Japanese travelers would present cannabis leaves as offerings at roadside shrines to ensure safe trips. Hemp was a strategic war crop for Japan during the Second World War, as it was for the United States and Europe, and was used to make rope and parachute cords. Following the conclusion of the war and subsequent occupation of Japan, a prohibition on cannabis production was enacted by the passing of the Cannabis Control Law (see Legal status below). While the ostensible purpose of the law was to protect Japanese society from narcotics, historians have speculated that American petrochemical interests may have sought to restrict the hemp fiber industry in order to open Japan to foreign-made polyester and nylon, noting that the sale of amphetamines was permitted until 1951. In any case, the opening of the Japanese economy under the occupied government saw the country flooded with foreign synthetic products that replaced many traditional Japanese goods, and effectively eliminated hemp cultivation in Japan in all but the most remote regions of the country. Spontaneous wild cannabis growth in urban areas (particularly in open environments along railway tracks) persisted until at least the mid-1950s, while wild cannabis growth persists in parts of Hokkaido; in 2003, Hokkaido's health and welfare bureau cut down 1.47 million wild cannabis plants, amounting to roughly 80 percent of the total wild cannabis in Japan.

In the months prior to the cultivation ban, Emperor Hirohito offered assurances that farms cultivating hemp for industrial use would be permitted to continue operating in defiance of the Cannabis Control Law. In 1950 there were approximately 25,000 cannabis farms in Japan, a number that would decline significantly in the subsequent decades due to a reduction in demand for hemp fiber and the cost of newly required hemp cultivation licenses. A 1968 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report noted that the majority of the violators of the country's cannabis laws were foreigners, principally foreign sailors and soldiers on leave from the Vietnam War. Cannabis gained some popularity as a recreational drug among Japanese domestics during the 1970s as disposable incomes rose, but remained generally less popular than solvents and amphetamines. In 1972, 853 violations of the Cannabis Control Law were recorded. Synthetic cannabinoids, referred to in Japan as dappo habu (literally "loophole herb"), gained popularity in the 2010s, but faced police crackdowns after two separate incidents in which drivers under the influence of synthetic cannabinoids struck pedestrians.

Legal status

Legislation and policy

The Cannabis Control Law is Japan's national law banning the import, export, cultivation, sale, purchase, and research of cannabis buds and leaves. Originally passed in July 1948, the law has subsequently been modified multiple times, with each revision adding stricter penalties for violations. Japan has also ratified the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.

Industrial hemp is legal under Japanese law, though its cultivation is strictly regulated (see Modern use below). Cannabidiol (CBD) and certain cannabis derivatives are legal due to a regulatory loophole that permits the importation of products made from cannabis stems and stalks that do not contain THC, though certain derivatives and synthetic cannabinoids such as HHC and CUMYL-CBMICA have been made illegal. The possession, sale, and cultivation of cannabis for both recreational and medicinal purposes is illegal, though a law legalizing medical cannabis was passed by the House of Councillors in December 2023.

Consumption of cannabis is legal, a legacy of an original provision of the Cannabis Control Law that did not punish consumption in order to shield hemp farmers who may unintentionally inhale the crop's psychoactive substances. In 2021, a Ministry of Health panel formally recommended that the Cannabis Control Law be revised to criminalize cannabis consumption (see Reform below).

Penalties and violations

Penalties for violations of Japan's cannabis laws are among the strictest in the world. Possession of cannabis carries a penalty of up to five years imprisonment, cultivation carries a penalty of up to seven years imprisonment, and possession for the purpose of trafficking carries a penalty of up to seven years imprisonment and a fine of ¥2 million (US$18,223.23). Cultivation and importation carry a penalty of up to seven years imprisonment, while cultivation and importation for the purpose of trafficking carries a penalty of up to ten years imprisonment and a fine of ¥3 million (US$27,335).

A report by the Ministry of Justice found that there were 2,423 violations to the Cannabis Control Law in 2006, an increase from 2,063 in 2005. The same report found that a total of 421 kg (928 lb) of marijuana was confiscated in 2006, compared with 972 kg (2143 lb) in 2005 and 1,055 kg (2325 lb) in 2004, a trend cited as possible evidence that casual marijuana use was on the rise among the broader population. In 2019 there were 4,570 violations – the sixth consecutive year of year-over-year increases – with nearly 60 percent of those arrested being aged 30 or younger.

In 2020, 5,034 people in Japan were convicted for cannabis-related crimes, compared to 8,471 convictions for crimes related to amphetamines, 201 for synthetic drugs, and 188 for cocaine. Of these 5,034 cannabis cases, 4,121 were for possession, 274 were for delivery, and 232 were for cultivation. 17.6 percent of cannabis offenders were between 14 and 19 years old, while 50.4 percent were between 20 and 29 years old. The majority of offenders reported that they began to use cannabis when they were 20 or younger and that they began using cannabis "after being invited to do so, citing curiosity as a reason for accepting such an invitation".

There have been several high-profile arrests and scandals relating to the possession or use of cannabis by public figures. In 1980, English musician Paul McCartney was detained in a Japanese prison for nine days after cannabis was found in his luggage at Tokyo's Narita International Airport. The 2008 sumo cannabis scandal resulted in the expulsion of four professional sumo wrestlers from the sport, and was described by The Japan Times as the largest drug-related sporting scandal in Japanese history. In 2009, professional rugby player Christian Loamanu of Toshiba Brave Lupus Tokyo was indefinitely suspended from the Japan Rugby Football Union after testing positive for cannabis in a random drug test. In 2017, actress Saya Takagi was sentenced to a three-year suspended sentence for possession of cannabis; she subsequently retired from acting to become a cannabis legalization activist. Actor and idol Junnosuke Taguchi was sentenced to a two-year suspended sentence for possession of cannabis in 2019, while actor Yusuke Iseya was sentenced to a three-year suspended sentence for possession of cannabis in 2020.

Modern use

As hemp

Hemp fibers and nongerminated hemp seeds are used in a variety of Japanese commercial products and religious items, such as shichimi spices, traditional shimenawa straw festoons, and noren curtain room dividers. Most hemp products in Japan are imported, though cannabis for use as hemp is cultivated domestically on a small scale. Permits to cultivate hemp are granted under a strictly regulated licensing system; in 2016, there were 37 licensed cannabis farms in Japan. The majority of these farms are in Tochigi Prefecture, a region that cultivates approximately 90 percent of Japan's commercial hemp, though these farms rarely exceed 10 hectares (25 acres) in size. Japanese hemp cultivators are required to grow Tochigishiro, a low THC strain with little euphoric potency that was developed after World War II and which is distributed to farmers as seeds by the government. Less than one hundred total licenses are granted to Shinto shrines, which grow and process small amounts of cannabis for ritual use.

As a drug

Marijuana is the second most commonly-used illicit drug in Japan behind methamphetamine. A 2019 survey found that 1.8 percent of people in Japan had used marijuana at least once in their lifetime, compared to 44.2 percent of Americans and 41.5 percent of Canadians, while 2018 survey by the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry [ja] found that 1.4 percent of people in Japan aged 15 to 64 (or 1.33 million people) had used marijuana. The total value of the cannabis market in Japan was estimated at ¥24 billion (US$218.68 million) in 2023.

Recreational cannabis usage in Japan has steadily increased since the 2000s, particularly among young people (see Penalties and violations above). Potential causes for this trend include the reduced availability of kiken (quasi-legal designer drugs) as a result of police crackdowns, and the ubiquity of positive information about cannabis available on the internet. Despite this, cannabis use continues to carry a strong social stigma in Japan, and individuals who are arrested or prosecuted for cannabis possession typically face social and professional consequences in addition to legal prosecution. For example, when actress turned cannabis activist Saya Takagi was arrested for cannabis possession in 2016, media companies removed her films and television episodes featuring her from circulation, and damaging stories about her personal life and marriage were published in the mainstream press.

While clandestine marijuana grow operations do operate in Japan, they are generally small in scale, and most cannabis in the country is imported. Per a UNODC survey, in 2010 a gram (1/28 oz) of ground cannabis sold at retail in Japan for an average of US$68.40, while a gram (1/28 oz) of hashish retailed for an average of US$91.10. A 2018 global cannabis price index based on UNODC data found that Tokyo was the most expensive city in the world to purchase cannabis, with a gram (1/28 oz) costing an average of US$32.66.

CBD is legal in Japan and been sold in the country since 2013, with CBD-infused products such as oils, cosmetics, and foodstuffs being readily available at both specialty shops and major retailers. The value of the CBD food market in Japan was an estimated US$10-18 million in 2020, representing an increase of 171 percent from 2019. Many Japanese CBD manufacturers intentionally dissociate their products from marijuana, for example, by avoiding packaging featuring marijuana leaf designs. While The New York Times reported in 2021 that Japanese authorities "haven't exactly encouraged the CBD industry, they largely view it as benign, in 2024 a proposed revision to the Cannabis Control Law was introduced that would restrict the amount of THC that CBD products can contain to 0.001% or less. The proposal has been strongly criticized by Japan's CBD industry, which has argued that the cap would constitute an effective ban on CBD.

Reform

The Japan Times reported in 2021 that "political momentum for legalizing cannabis" in Japan "is essentially nonexistent". While several industrialized nations have moved to relax laws concerning cannabis in recent decades, Japan has maintained and strengthened laws that prohibit the use, possession, and cultivation of cannabis. The Cannabis Control Law was upheld by the Supreme Court of Japan in a 1985 challenge, while the Japanese Drug Abuse Prevention Center (an organization under the supervision of the Ministry of Health and the National Police Agency) maintains a policy that cannabis is harmful to the immune and respiratory systems, and can induce manic-depression.

A 2012 projection by author and businessman Funai Yukio [ja] estimated that legalizing recreational cannabis in Japan could generate up to ¥30 trillion (US$273 billion) in revenue. Multiple pro-legalization organizations have formed since the 1990s: in 1999, the Japanese Medical Marijuana Association was formed to advocate for the legalization of medical cannabis. In 2001, the Cannabis Museum was opened by hemp rights advocate Junichi Takayasu, which "works to elevate the degraded standing of cannabis by educating the public about the history of hemp in Japan". Japanese legalization activists have emulated tactics used by activists in the United States by publicizing reports on the effectiveness of cannabis in treating pediatric epilepsy and other ailments, with the goal of shifting public opinion in order to provoke legal changes. Few politicians have indicated support for reformist policies; in 2017, the now-defunct New Renaissance Party was the first Japanese political party to endorse the legalization of medical cannabis. Akie Abe, wife of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, has advocated for greater investment in Japanese industrial hemp farming, and has indicated support for the legalization of medical cannabis.

In 2021, the Ministry of Health convened a panel of experts to make recommendations on potential revisions to the Cannabis Control Law. In its report the panel recommended that cannabis consumption be formally criminalized, that cannabis regulations shift from the current system of regulating leaves and buds to regulating cannabis' chemical compounds, and to permit clinical trials of cannabis-derived pharmaceuticals such as Epidiolex. In December 2023, the House of Councillors passed a law that would legalize medicinal cannabis, criminalize non-medical cannabis consumption, and introduce a new licensing system for cannabis growers. If adopted, the provisions relating to medical cannabis will come into effect one year from promulgation, while the provisions relating to licensing will come into effect two years from promulgation.

See also

Notes

- Woven hemp bags were traditionally used to detoxify horse-chestnuts and other wild foods.

- In a notable exception, a 2016 raid in Wakayama Prefecture resulted in the seizure of over 10,000 cannabis plants, which police deemed an "extraordinary amount" compared to past raids.

References

- Citations

- ^ Mitchell 2014.

- Ferraria, Becky (18 April 2017). "A Visual History of the Pot Leaf". Vice. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 96.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 153.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 95.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 155.

- Clarke & Merlin 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon (13 December 2015). "Cannabis: The fabric of Japan". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 97.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 154.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 98.

- Clarke & Merlin 2013, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 156.

- ^ Hongo, Jun (11 December 2007). "Hemp OK as rope, not as dope". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Nagahama, Masamutsu (1 January 1968). "A review of drug abuse and countermeasures in Japan since World War II". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Roman, Ahn-Redding & Simon 2007, p. 174.

- Miles 1984, p. 67.

- ^ Montgomery, Hanako (29 June 2022). "A Loophole in Japan's Weed Laws Is Getting Tens of Thousands High". Vice. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Osaki, Tomohiro (22 January 2021). "New panel to probe growing use of marijuana and stiffen draconian pot law". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Roman, Ahn-Redding & Simon 2007, p. 172.

- ^ Dooley, Ben; Hida, Hikari (27 October 2021). "Japan Stays Tough on Cannabis as Other Nations Loosen Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Japan's parliament passes bill to legalize cannabis-derived medicines". The Japan Times. 6 December 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Hari, Johann (11 May 2018). "Japan, the place with the strangest drug debate in the world". OpenDemocracy. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- "大麻取締法" [Cannabis Control Law]. e-Gov Japan (in Japanese). Government of Japan. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Jiji, Kyodo (8 April 2021). "Japan sees record cannabis offenders above 5,000 in 2020". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Martoccio, Angie (30 August 2021). "Flashback: Lee 'Scratch' Perry Tries to Bust Paul McCartney Out of Prison for Weed Possession". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- "暴行死に賭博、八百長も/角界の主な不祥事" [Violent Deaths, Gambling, and Eighty-Four Millionaires: Major Scandals in Sumo]. Nikkan Sports (in Japanese). 29 November 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Talmadge, Eric (12 February 2009). "Nation grapples with pot-smoking sumo wrestlers". The Japan Times. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- "Loamanu suspended for using pot". The Japan Times. 14 February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- "Ex-actress Takagi gets suspended one-year sentence for marijuana possession". The Japan Times. 27 April 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Brasor, Philip (5 November 2016). "Japan's war against medical marijuana". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- "Former Kat-tun member Junnosuke Taguchi gets suspended term for marijuana possession". The Japan times. 21 October 2019. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Siripala, Thisanka (11 June 2019). "Japan's Police Struggle to Curb a Sharp Increase in Cannabis Use". The Diplomat. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Yan, Lim Ruey (23 December 2020). "Japanese actor Yusuke Iseya given suspended jail sentence for drug possession". The Straits Times. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Clarke & Merlin 2013, p. 157.

- Brownfield 2010, p. 380.

- "大麻経験、推計133万人" [Marijuana use estimated at 1.33 million people]. The Nikkei (in Japanese). 18 June 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Otake, Tomoko (9 May 2024). "Japan's cannabis market growing rapidly amid regulatory shift". The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- Brownfield 2010, p. 382.

- "Police raid on rural Wakayama factory nets ¥2 billion in cannabis plants". The Japan Times. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- "Marijuana (herb) retail and wholesale prices and purity levels, by drug, region and country or territory" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- Connaughton, Maddison (30 January 2018). "Tokyo Is the Most Expensive Place in the World to Buy Weed". Vice. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Mahoney, Luke (25 June 2020). "Does hemp have a home in Japan?". Japan Today. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "Japan: The Japanese Market for CBD and Hemp Extracts". Foreign Agricultural Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 9 August 2023. p. 9. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- Ewe, Koh (21 June 2024). "Japan's Crackdown on Cannabis and CBD Throws a Booming Market Into Uncertainty". Time. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- Osaki, Tomohiro. "Japan steps up marijuana warnings following legalization in New York". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ Takenaka, Kiyoshi (7 July 2016). "Japan party backs use of medical marijuana, gets mixed reaction". Reuters. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "Japan to criminalize cannabis use, but allow medical marijuana: expert panel report". The Mainichi. 12 June 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- Bibliography

- Brownfield, William R., ed. (2010). International Narcotics Control Strategy Report: Volume I: Drug and Chemical Control. Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.

- Clarke, Robert; Merlin, Mark (2013). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520954571.

- Miles, J. A. R. (1984). Public Health Progress in the Pacific: Geographical Background and Regional Development. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789027790859.

- Mitchell, Jon (2014). "The Secret History of Cannabis in Japan". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 12 (49).

- Roman, Caterina Gouvis; Ahn-Redding, Heather; Simon, Rita James (2007). Illicit Drug Policies, Trafficking, and Use the World Over. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2088-0.

| Cannabis in Japan | |

|---|---|

| Law | |

| Organizations | |

| People | |

| History | |