In geometry, the incenter of a triangle is a triangle center, a point defined for any triangle in a way that is independent of the triangle's placement or scale. The incenter may be equivalently defined as the point where the internal angle bisectors of the triangle cross, as the point equidistant from the triangle's sides, as the junction point of the medial axis and innermost point of the grassfire transform of the triangle, and as the center point of the inscribed circle of the triangle.

Together with the centroid, circumcenter, and orthocenter, it is one of the four triangle centers known to the ancient Greeks, and the only one of the four that does not in general lie on the Euler line. It is the first listed center, X(1), in Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers, and the identity element of the multiplicative group of triangle centers.

For polygons with more than three sides, the incenter only exists for tangential polygons: those that have an incircle that is tangent to each side of the polygon. In this case the incenter is the center of this circle and is equally distant from all sides.

Definition and construction

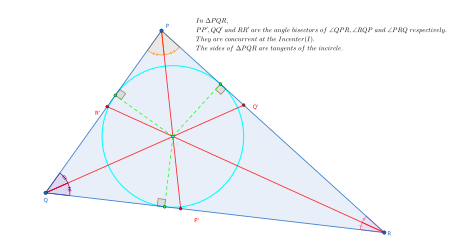

It is a theorem in Euclidean geometry that the three interior angle bisectors of a triangle meet in a single point. In Euclid's Elements, Proposition 4 of Book IV proves that this point is also the center of the inscribed circle of the triangle. The incircle itself may be constructed by dropping a perpendicular from the incenter to one of the sides of the triangle and drawing a circle with that segment as its radius.

The incenter lies at equal distances from the three line segments forming the sides of the triangle, and also from the three lines containing those segments. It is the only point equally distant from the line segments, but there are three more points equally distant from the lines, the excenters, which form the centers of the excircles of the given triangle. The incenter and excenters together form an orthocentric system.

The medial axis of a polygon is the set of points whose nearest neighbor on the polygon is not unique: these points are equidistant from two or more sides of the polygon. One method for computing medial axes is using the grassfire transform, in which one forms a continuous sequence of offset curves, each at some fixed distance from the polygon; the medial axis is traced out by the vertices of these curves. In the case of a triangle, the medial axis consists of three segments of the angle bisectors, connecting the vertices of the triangle to the incenter, which is the unique point on the innermost offset curve. The straight skeleton, defined in a similar way from a different type of offset curve, coincides with the medial axis for convex polygons and so also has its junction at the incenter.

Proofs

Ratio proof

Let the bisection of and meet at , and the bisection of and meet at , and and meet at .

And let and meet at .

Then we have to prove that is the bisection of .

In , , by the Angle bisector theorem.

In , .

Therefore, , so that .

So is the bisection of .

Perpendicular proof

A line that is an angle bisector is equidistant from both of its lines when measuring by the perpendicular. At the point where two bisectors intersect, this point is perpendicularly equidistant from the final angle's forming lines (because they are the same distance from this angles opposite edge), and therefore lies on its angle bisector line.

Relation to triangle sides and vertices

Trilinear coordinates

The trilinear coordinates for a point in the triangle give the ratio of distances to the triangle sides. Trilinear coordinates for the incenter are given by

The collection of triangle centers may be given the structure of a group under coordinatewise multiplication of trilinear coordinates; in this group, the incenter forms the identity element.

Barycentric coordinates

The barycentric coordinates for a point in a triangle give weights such that the point is the weighted average of the triangle vertex positions. Barycentric coordinates for the incenter are given by

where , , and are the lengths of the sides of the triangle, or equivalently (using the law of sines) by

where , , and are the angles at the three vertices.

Cartesian coordinates

The Cartesian coordinates of the incenter are a weighted average of the coordinates of the three vertices using the side lengths of the triangle relative to the perimeter—i.e., using the barycentric coordinates given above, normalized to sum to unity—as weights. (The weights are positive so the incenter lies inside the triangle as stated above.) If the three vertices are located at , , and , and the sides opposite these vertices have corresponding lengths , , and , then the incenter is at

Distances to vertices

Denoting the incenter of triangle ABC as I, the distances from the incenter to the vertices combined with the lengths of the triangle sides obey the equation

Additionally,

where R and r are the triangle's circumradius and inradius respectively.

Related constructions

Other centers

The distance from the incenter to the centroid is less than one third the length of the longest median of the triangle.

By Euler's theorem in geometry, the squared distance from the incenter I to the circumcenter O is given by

where R and r are the circumradius and the inradius respectively; thus the circumradius is at least twice the inradius, with equality only in the equilateral case.

The distance from the incenter to the center N of the nine point circle is

The squared distance from the incenter to the orthocenter H is

Inequalities include:

The incenter is the Nagel point of the medial triangle (the triangle whose vertices are the midpoints of the sides) and therefore lies inside this triangle. Conversely the Nagel point of any triangle is the incenter of its anticomplementary triangle.

The incenter must lie in the interior of a disk whose diameter connects the centroid G and the orthocenter H (the orthocentroidal disk), but it cannot coincide with the nine-point center, whose position is fixed 1/4 of the way along the diameter (closer to G). Any other point within the orthocentroidal disk is the incenter of a unique triangle.

Euler line

The Euler line of a triangle is a line passing through its circumcenter, centroid, and orthocenter, among other points. The incenter generally does not lie on the Euler line; it is on the Euler line only for isosceles triangles, for which the Euler line coincides with the symmetry axis of the triangle and contains all triangle centers.

Denoting the distance from the incenter to the Euler line as d, the length of the longest median as v, the length of the longest side as u, the circumradius as R, the length of the Euler line segment from the orthocenter to the circumcenter as e, and the semiperimeter as s, the following inequalities hold:

Area and perimeter splitters

Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle's area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle's incenter; every line through the incenter that splits the area in half also splits the perimeter in half. There are either one, two, or three of these lines for any given triangle.

Relative distances from an angle bisector

Let X be a variable point on the internal angle bisector of A. Then X = I (the incenter) maximizes or minimizes the ratio along that angle bisector.

References

- Kimberling, Clark (1994), "Central Points and Central Lines in the Plane of a Triangle", Mathematics Magazine, 67 (3): 163–187, doi:10.1080/0025570X.1994.11996210, JSTOR 2690608, MR 1573021.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers Archived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2014-10-28.

- Euclid's Elements, Book IV, Proposition 4: To inscribe a circle in a given triangle. David Joyce, Clark University, retrieved 2014-10-28.

- Johnson, R. A. (1929), Modern Geometry, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, p. 182.

- Blum, Harry (1967), "A transformation for extracting new descriptors of shape", in Wathen-Dunn, Weiant (ed.), Models for the Perception of Speech and Visual Form (PDF), Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 362–380,

In the triangle three corners start propagating and disappear at the center of the largest inscribed circle

. - Aichholzer, Oswin; Aurenhammer, Franz; Alberts, David; Gärtner, Bernd (1995), "A novel type of skeleton for polygons", Journal of Universal Computer Science, 1 (12): 752–761, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-80350-5_65, MR 1392429.

- Allaire, Patricia R.; Zhou, Junmin; Yao, Haishen (March 2012), "Proving a nineteenth century ellipse identity", Mathematical Gazette, 96 (535): 161–165, doi:10.1017/S0025557200004277.

- Altshiller-Court, Nathan (1980), College Geometry, Dover Publications. #84, p. 121.

- Franzsen, William N. (2011), "The distance from the incenter to the Euler line" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 11: 231–236, MR 2877263, archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-05, retrieved 2014-10-28. Lemma 3, p. 233.

- Johnson (1929), p. 186

- ^ Franzsen (2011), p. 232.

- Dragutin Svrtan and Darko Veljan, "Non-Euclidean versions of some classical triangle inequalities", Forum Geometricorum 12 (2012), 197–209. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2012volume12/FG201217index.html Archived 2019-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Marie-Nicole Gras, "Distances between the circumcenter of the extouch triangle and the classical centers" Forum Geometricorum 14 (2014), 51-61. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2014volume14/FG201405index.html Archived 2021-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Franzsen (2011), Lemma 1, p. 233.

- Franzsen (2011), p. 232.

- Schattschneider, Doris; King, James (1997), Geometry Turned On: Dynamic Software in Learning, Teaching, and Research, The Mathematical Association of America, pp. 3–4, ISBN 978-0883850992

- Edmonds, Allan L.; Hajja, Mowaffaq; Martini, Horst (2008), "Orthocentric simplices and biregularity", Results in Mathematics, 52 (1–2): 41–50, doi:10.1007/s00025-008-0294-4, MR 2430410, S2CID 121434528,

It is well known that the incenter of a Euclidean triangle lies on its Euler line connecting the centroid and the circumcenter if and only if the triangle is isosceles

. - Franzsen (2011), pp. 232–234.

- Kodokostas, Dimitrios (April 2010), "Triangle equalizers", Mathematics Magazine, 83 (2): 141–146, doi:10.4169/002557010X482916, S2CID 218541138.

- Arie Bialostocki and Dora Bialostocki, "The incenter and an excenter as solutions to an extremal problem", Forum Geometricorum 11 (2011), 9-12. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2011volume11/FG201102index.html

- Hajja, Mowaffaq, Extremal properties of the incentre and the excenters of a triangle", Mathematical Gazette 96, July 2012, 315-317.

and

and  meet at

meet at  , and the bisection of

, and the bisection of  and

and  meet at

meet at  , and

, and  and

and  meet at

meet at  .

.

and

and  meet at

meet at  .

.

.

.

,

,  , by the

, by the  ,

,  .

.

, so that

, so that  .

.

is the bisection of

is the bisection of

,

,  , and

, and  are the lengths of the sides of the triangle, or equivalently (using the

are the lengths of the sides of the triangle, or equivalently (using the

,

,  , and

, and  are the angles at the three vertices.

are the angles at the three vertices.

,

,  , and

, and  , and the sides opposite these vertices have corresponding lengths

, and the sides opposite these vertices have corresponding lengths

along that angle bisector.

along that angle bisector.