| This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Online community" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

An online community, also called an internet community or web community, is a community whose members interact with each other primarily via the Internet. Members of the community usually share common interests. For many, online communities may feel like home, consisting of a "family of invisible friends". Additionally, these "friends" can be connected through gaming communities and gaming companies. Those who wish to be a part of an online community usually have to become a member via a specific site and just to specific content or links.

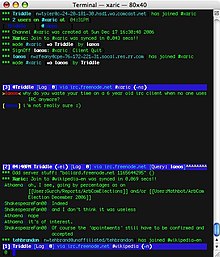

An online community can act as an information system where members can post, comment on discussions, give advice or collaborate, and includes medical advice or specific health care research as well. Commonly, people communicate through social networking sites, chat rooms, forums, email lists, and discussion boards, and have advanced into daily social media platforms as well. This includes Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Discord, etc. People may also join online communities through video games, blogs, and virtual worlds, and could potentially meet new significant others in dating sites or dating virtual worlds.

The rise in popularity of Web 2.0 websites has allowed for easier real-time communication and connection to others and facilitated the introduction of new ways for information to be exchanged. Yet, these interactions may also lead to a downfall of social interactions or deposit more negative and derogatory forms of speaking to others, in connection, surfaced forms of racism, bullying, sexist comments, etc. may also be investigated and linked to online communities.

One scholarly definition of an online community is this: "a virtual community is defined as an aggregation of individuals or business partners who interact around a shared interest, where the interaction is at least partially supported or mediated by technology (or both) and guided by some protocols or norms".

Purpose

Digital communities (web communities but also communities that are formed over, e.g., Xbox and PlayStation) provide a platform for a range of services to users. It has been argued that they can fulfill Maslow's hierarchy of needs. They allow for social interaction across the world between people of different cultures who might not otherwise have met with offline meetings also becoming more common. Another key use of web communities is access to and the exchange of information. With communities for even very small niches it is possible to find people also interested in a topic and to seek and share information on a subject where there are not such people available in the immediate area offline. This has led to a range of popular sites based on areas such as health, employment, finances and education. Online communities can be vital for companies for marketing and outreach.

Unexpected and innovative uses of web communities have also emerged with social networks being used in conflicts to alert citizens of impending attacks. The UN sees the web and specifically social networks as an important tool in conflicts and emergencies.

Web communities have grown in popularity; as of October 2014, 6 of the 20 most-trafficked websites were community-based sites. The amount of traffic to such websites is expected to increase as a growing proportion of the world's population attains Internet access.

Categorization

The idea of a community is not a new concept. On the telephone, in ham radio and in the online world, social interactions no longer have to be based on proximity; instead they can literally be with anyone anywhere. The study of communities has had to adapt along with the new technologies. Many researchers have used ethnography to attempt to understand what people do in online spaces, how they express themselves, what motivates them, how they govern themselves, what attracts them, and why some people prefer to observe rather than participate. Online communities can congregate around a shared interest and can be spread across multiple websites.

Some features of online communities include:

- Content: articles, information, and news about a topic of interest to a group of people.

- Forums or newsgroups and email: so that community members can communicate in delayed fashion.

- Chat and instant messaging: so that community members can communicate more immediately.

Development

Online communities typically establish a set of values, sometimes known collectively as netiquette or Internet etiquette, as they grow. These values may include: opportunity, education, culture, democracy, human services, equality within the economy, information, sustainability, and communication. An online community's purpose is to serve as a common ground for people who share the same interests.

Online communities may be used as calendars to keep up with events such as upcoming gatherings or sporting events. They also form around activities and hobbies. Many online communities relating to health care help inform, advise, and support patients and their families. Students can take classes online and they may communicate with their professors and peers online. Businesses have also started using online communities to communicate with their customers about their products and services as well as to share information about the business. Other online communities allow a wide variety of professionals to come together to share thoughts, ideas and theories.

Fandom is an example of what online communities can evolve into. Online communities have grown in influence in "shaping the phenomena around which they organize" according to Nancy K. Baym's work. She says that: "More than any other commercial sector, the popular culture industry relies on online communities to publicize and provide testimonials for their products." The strength of the online community's power is displayed through the season 3 premiere of BBC's Sherlock. Online activity by fans seem to have had a noticeable influence on the plot and direction of the season opening episode. Mark Lawson of The Guardian recounts how fans have, to a degree, directed the outcome of the events of the episode. He says that "Sherlock has always been one of the most web-aware shows, among the first to find a satisfying way of representing electronic chatter on-screen." Fan communities in platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Reddit around sports, actors, and musicians have become powerful communities both culturally and politically.

Discussions where members may post their feedback are essential in the development of an online community. Online communities may encourage individuals to come together to teach and learn from one another. They may encourage learners to discuss and learn about real-world problems and situations, as well as to focus on such things as teamwork, collaborative thinking and personal experiences.

Blogs

Blogs are among the major platforms on which online communities form. Blogging practices include microblogging, where the amount of information in a single element is smaller, and liveblogging, in which an ongoing event is blogged about in real time.

The ease and convenience of blogging has allowed for its growth. Major blogging platforms include Twitter and Tumblr, which combine social media and blogging, as well as platforms such as WordPress, which allow content to be hosted on their own servers but also permit users to download, install, and modify the software on their own servers. As of October 2014, 23.1% of the top 10 million websites are either hosted on or run WordPress.

Forums

Internet forums, sometimes called bulletin boards, are websites which allow users to post topics also known as threads for discussion with other users able to reply creating a conversation. Forums follow a hierarchical structure of categories, with many popular forum software platforms categorising forums depending on their purpose, and allowing forum administrators to create subforums within their platform. With time more advanced features have been added into forums; the ability to attach files, embed YouTube videos, and send private messages is now commonplace. As of October 2014, the largest forum Gaia Online contained over 2 billion posts.

Members are commonly assigned into user groups which control their access rights and permissions. Common access levels include the following:

- User: A standard account with the ability to create topics and reply.

- Moderator: Moderators are typically tasked with the daily administration tasks such as answering user queries, dealing with rule-breaking posts, and the moving, editing or deletion of topics or posts.

- Administrator: Administrators deal with the forum strategy including the implementation of new features alongside more technical tasks such as server maintenance.

Social networks

Social networks are platforms allowing users to set up their own profile and build connections with like minded people who pursue similar interests through interaction. The first traceable example of such a site is SixDegrees.com, set up in 1997, which included a friends list and the ability to send messages to members linked to friends and see other users associations. For much of the 21st century, the popularity of such networks has been growing. Friendster was the first social network to gain mass media attention; however, by 2004 it had been overtaken in popularity by Myspace, which in turn was later overtaken by Facebook. In 2013, Facebook attracted 1.23 billion monthly users, rising from 145 million in 2008. Facebook was the first social network to surpass 1 billion registered accounts, and by 2020, had more than 2.7 billion active users. Meta Platforms, the owner of Facebook, also owns three other leading platforms for online communities: Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook Messenger.

Most top-ranked social networks originate in the United States, but European services like VK, Japanese platform LINE, or Chinese social networks WeChat, QQ or video-sharing app Douyin (internationally known as TikTok) have also garnered appeal in their respective regions.

Current trends focus around the increased use of mobile devices when using social networks. Statistics from Statista show that, in 2013, 97.9 million users accessed social networks from a mobile device in the United States.

Classification

Researchers and organizations have worked to classify types of online community and to characterise their structure. For example, it is important to know the security, access, and technology requirements of a given type of community as it may evolve from an open to a private and regulated forum. It has been argued that the technical aspects of online communities, such as whether pages can be created and edited by the general user base (as is the case with wikis) or only certain users (as is the case with most blogs), can place online communities into stylistic categories. Another approach argues that "online community" is a metaphor and that contributors actively negotiate the meaning of the term, including values and social norms.

Some research has looked at the users of online communities. Amy Jo Kim has classified the rituals and stages of online community interaction and called it the "membership life cycle". Clay Shirky talks about communities of practice, whose members collaborate and help each other in order to make something better or improve a certain skill. What makes these communities bond is "love" of something, as demonstrated by members who go out of their way to help without any financial interest. Campbell et al. developed a character theory for analyzing online communities, based on tribal typologies. In the communities they investigated they identified three character types:

- The Big Man (offer a form of order and stability to the community by absorbing many conflictual situations personally)

- The Sorcerer (will not engage in reciprocity with others in the community)

- The Trickster (generally a comical yet complex figure that is found in most of the world's culture)

Online communities have also forced retail firms to change their business strategies. Companies have to network more, adjust computations, and alter their organizational structures. This leads to changes in a company's communications with their manufacturers including the information shared and made accessible for further productivity and profits. Because consumers and customers in all fields are becoming accustomed to more interaction and engagement online, adjustments must be considered made in order to keep audiences intrigued.

Online communities have been characterized as "virtual settlements" that have the following four requirements: interactivity, a variety of communicators, a common public place where members can meet and interact, and sustained membership over time. Based on these considerations, it can be said that microblogs such as Twitter can be classified as online communities.

Building communities

Dorine C. Andrews argues, in the article "Audience-Specific Online Community Design", that there are three parts to building an online community: starting the online community, encouraging early online interaction, and moving to a self-sustaining interactive environment. When starting an online community, it may be effective to create webpages that appeal to specific interests. Online communities with clear topics and easy access tend to be most effective. In order to gain early interaction by members, privacy guarantees and content discussions are very important. Successful online communities tend to be able to function self-sufficiently.

Participation

There are two major types of participation in online communities: public participation and non-public participation, also called lurking. Lurkers are participants who join a virtual community but do not contribute. In contrast, public participants, or posters, are those who join virtual communities and openly express their beliefs and opinions. Both lurkers and posters frequently enter communities to find answers and to gather general information. For example, there are several online communities dedicated to technology. In these communities, posters are generally experts in the field who can offer technological insight and answer questions, while lurkers tend to be technological novices who use the communities to find answers and to learn.

In general, virtual community participation is influenced by how participants view themselves in society as well as by norms, both of society and of the online community. Participants also join online communities for friendship and support. In a sense, virtual communities may fill social voids in participants' offline lives.

Sociologist Barry Wellman presents the idea of "globalization" – the Internet's ability to extend participants' social connections to people around the world while also aiding them in further engagement with their local communities.

Roles in an online community

Although online societies differ in content from real society, the roles people assume in their online communities are quite similar. Elliot Volkman points out several categories of people that play a role in the cycle of social networking, such as:

- Community architect – Creates the online community, sets goals and decides the purpose of the site.

- Community manager – Oversees the progress of the society. Enforces rules, encourages social norms, assists new members, and spreads awareness about the community.

- Professional member – This is a member who is paid to contribute to the site. The purpose of this role is to keep the community active.

- Free members – These members visit sites most often and represent the majority of the contributors. Their contributions are crucial to the sites' progress.

- Passive lurker – These people do not contribute to the site but rather absorb the content, discussion, and advice.

- Active lurker – Consumes the content and shares that content with personal networks and other communities.

- Power users – These people push for new discussion, provide positive feedback to community managers, and sometimes even act as community managers themselves. They have a major influence on the site and make up only a small percentage of the users.

Aspects of successful online communities

An article entitled "The real value of on-line communities," written by A. Armstrong and John Hagel of the Harvard Business Review, addresses a handful of elements that are key to the growth of an online community and its success in drawing in members. In this example, the article focuses specifically on online communities related to business, but its points can be transferred and can apply to any online community. The article addresses four main categories of business-based online communities, but states that a truly successful one will combine qualities of each of them: communities of transaction, communities of interest, communities of fantasy, and communities of relationship. Anubhav Choudhury describes the four types of community as follows:

- Communities of transaction emphasize the importance of buying and selling products in a social online manner where people must interact in order to complete the transaction.

- Communities of interest involve the online interaction of people with specific knowledge on a certain topic.

- Communities of fantasy encourage people to participate in online alternative forms of reality, such as games where they are represented by avatars.

- Communities of relationship often reveal or at least partially protect someone's identity while allowing them to communicate with others, such as in online dating services.

Membership lifecycle

Amy Jo Kim's membership lifecycle theory states that members of online communities begin their life in a community as visitors, or lurkers. After breaking through a barrier, people become novices and participate in community life. After contributing for a sustained period of time, they become regulars. If they break through another barrier they become leaders, and once they have contributed to the community for some time they become elders. This life cycle can be applied to many virtual communities, such as bulletin board systems, blogs, mailing lists, and wiki-based communities like Misplaced Pages.

A similar model can be found in the works of Lave and Wenger, who illustrate a cycle of how users become incorporated into virtual communities using the principles of legitimate peripheral participation. They suggest five types of trajectories amongst a learning community:

- Peripheral (i.e. Lurker) – An outside, unstructured participation

- Inbound (i.e. Novice) – Newcomer is invested in the community and heading towards full participation

- Insider (i.e. Regular) – Full committed community participant

- Boundary (i.e. Leader) – A leader, sustains membership participation and brokers interactions

- Outbound (i.e. Elder) – Process of leaving the community due to new relationships, new positions, new outlooks

The following shows the correlation between the learning trajectories and Web 2.0 community participation by using the example of YouTube:

- Peripheral (Lurker) – Observing the community and viewing content. Does not add to the community content or discussion. The user occasionally goes onto YouTube.com to check out a video that someone has directed them to.

- Inbound (Novice) – Just beginning to engage with the community. Starts to provide content. Tentatively interacts in a few discussions. The user comments on other users' videos. Potentially posts a video of their own.

- Insider (Regular) – Consistently adds to the community discussion and content. Interacts with other users. Regularly posts videos. Makes a concerted effort to comment and rate other users' videos.

- Boundary (Leader) – Recognized as a veteran participant, their opinions are granted greater consideration by the community. Connects with regulars to make higher-concept ideas. The user has become recognized as a contributor to watch. Their videos may be podcasts commenting on the state of YouTube and its community. The user would not consider watching another user's videos without commenting on them. Will often correct a user in behavior the community considers inappropriate. Will reference other users' videos in their comments as a way to cross link content.

- Outbound (Elders) – Leave the community. Their interests may have changed, the community may have moved in a direction that they disagree with, or they may no longer have time to maintain a constant presence in the community.

Newcomers

Newcomers are important for online communities. Online communities rely on volunteers' contribution, and most online communities face high turnover rate as one of their main challenges. For example, only a minority of Misplaced Pages users contribute regularly, and only a minority of those contributors participate in community discussions. In one study conducted by Carnegie Mellon University, they found that "more than two-thirds (68%) of newcomers to Usenet groups were never seen again after their first post". Above facts reflect a point that recruiting and remaining new members have become a very crucial problem for online communities: the communities will eventually wither away without replacing members who leave.

Newcomers are new members of the online communities and thus often face many barriers when contributing to a project, and those barriers they face might lead them to give up the project or even leave the community. By conducting a systematic literature review over 20 primary studies regarding to the barriers faced by newcomers when contributing to the open source software projects, Steinmacher et al. identified 15 different barriers and they classified those barriers into five categories as described below:

- Social Interaction: this category describes the barriers when newcomers interact with existing members of the community. The three barriers that they found have main influence on newcomers are: "lack of social interaction with project members",'"not receiving a timely response", and "receiving an improper response".

- Newcomers' Previous Knowledge: this category describes the barriers which is regarding to the newcomers' previous experience related to this project. The three barriers they found classified into this part are: "lack of domain expertise", "lack of technical expertise", and "lack of knowledge of project practices".

- Finding a Way to Start: this category describes the issues when newcomers try to start contributing. The two barriers they found are: "Difficulty to find an appropriate task to start with", and "Difficulty to find a mentor".

- Documentation: documentation of the project also shown to be barriers for newcomers especially in the Open Source Software projects. The three barriers they found are: "Outdated documentation", "Too much documentation", and "Unclear code comments".

- Technical Hurdles: technical barriers are also one of the major issue when newcomers start contributing. This category includes barriers: "Issues setting up a local workspace", "Code complexity" and "Software architecture complexity".

Because of the barriers described above, it is very necessary that online communities engage newcomers and help them to adjust to the new environment. From online communities' side, newcomers can be both beneficial and harmful to online communities. On the one side, newcomers can bring online communities innovative ideas and resources. On the other side, they can also harm communities with misbehavior caused by their unfamiliarity with community norms. Kraut et al. defined five basic issues faced by online communities when dealing with newcomers, and proposed several design claims for each problem in their book Building Successful Online Communities.

- Recruitment. Online communities need to keep recruiting new members in the face of high turnover rate of their existing members. Three suggestions are made in the book:

- Interpersonal recruitment: recruit new members by old members' personal relationship

- Word of mouth recruitment: new members will join in the community because of the word-of-mouth influence from existing member

- Impersonal advertisement: although the direct effect is weaker than previous two strategies, impersonal advertising can effectively increase number of people joining among potential members with little prior knowledge of the community.

- Selection. Another challenge for online communities is to select the members who are a good fit. Unlike the offline organizations, the problem of selecting right candidates is more problematic for online communities since the anonymity of the users and the ease of creating new identities online. Two approaches are suggested in the book:

- Self-selection: make sure that only good fit members will choose to join.

- Screen: make sure that only good fit members will allow to join.

- Keeping Newcomers Around. Before new members start feel the commitment and do major contribution, they must be around long enough in online communities to learn the norms and form the community attachment. However, the majority of them tend to leave the communities at this period of time. At this period of time, new members are usually very sensitive to either positive or negative evidence they received from group, which may largely impact the users' decision on whether they quit or stay. Authors suggested two approaches:

- Entry Barriers: Higher entry barriers will be more likely to drive away new members, but those members who survived from this severe initiation process should have stronger commitment than those members with lower entry barriers.

- Interactions with existing members: communicating with existing members and receiving friendly responses from them will encourage the new members' commitment. The existing members are encouraged to treat the newcomers gently. One study by Halfaker et al. suggested that reverting new members' work in Misplaced Pages will likely to make them leave the communities. Thus, new members are more likely to stay and develop commitment if the interaction between existing member and new members are friendly and gentle. The book suggested different ways, including "introduction threads" in the communities, "assign the responsibilities of having friendly interactions with newcomers to designated older-timers", and "discouraging hostility towards newcomers who make mistakes".

- Socialization. Different online communities have their own norms and regulations, and new members need to learn to participate in an appropriate way. Thus, socialization is a process through which new members acquire the behaviors and attitude essential to playing their roles in a group or organization. Previous research in organizational socialization demonstrated that newcomers' active information seeking and organizational socialization tactics are associated with better performance, higher job satisfaction, more committed to the organization, more likely to stay and thus lower turnover rate. However, this institutionalized socialization tactics are not popular used in online setting, and most online communities are still using the individualized socialization tactics where newcomers being socialized individually and in a more informal way in their training process. Thus, in order to keep new members, the design suggestions given by this book are: "using formal, sequential and collective socialization tactics" and "old-timers can provide formal mentorship to newcomers."

- Protection. Newcomers are different from the existing members, and thus the influx of newcomers might change the environment or the culture developed by existing members. New members might also behave inappropriately, and thus be potentially harmful to online communities, as a result of their lack of experience. Different communities might also have different level of damage tolerance, some might be more fragile to newcomers' inappropriate behavior (such as open source group collaboration software project) while others are not (such as some discussion forums). So the speed of integrating new members with existing communities really depends on community types and its goals, and groups need to have protection mechanisms that serve to multiple purposes.

Motivations and barriers to participation

Main article: Motivations for online participationSuccessful online communities motivate online participation. Methods of motivating participation in these communities have been investigated in several studies.

There are many persuasive factors that draw users into online communities. Peer-to-peer systems and social networking sites rely heavily on member contribution. Users' underlying motivations to involve themselves in these communities have been linked to some persuasion theories of sociology.

- According to the reciprocation theory, a successful online community must provide its users with benefits that compensate for the costs of time, effort and materials members provide. People often join these communities expecting some sort of reward.

- The consistency theory says that once people make a public commitment to a virtual society, they will often feel obligated to stay consistent with their commitment by continuing contributions.

- The social validation theory explains how people are more likely to join and participate in an online community if it is socially acceptable and popular.

One of the greatest attractions towards online communities is the sense of connection users build among members. Participation and contribution are influenced when members of an online community are aware of their global audience.

The majority of people learn by example and often follow others, especially when it comes to participation. Individuals are reserved about contributing to an online community for many reasons including but not limited to a fear of criticism or inaccuracy. Users may withhold information that they do not believe is particularly interesting, relevant, or truthful. In order to challenge these contribution barriers, producers of these sites are responsible for developing knowledge-based and foundation-based trust among the community.

Users' perception of audience is another reason that makes users participate in online communities. Results showed that users usually underestimate their amount of audiences in online communities. Social media users guess that their audience is 27% of its real size. Regardless of this underestimation, it is shown that amount of audience affects users' self-presentation and also content production which means a higher level of participation.

There are two types of virtual online communities (VOC): dependent and self-sustained VOCs. The dependent VOCs are those who use the virtual community as extensions of themselves, they interact with people they know. Self-sustained VOCs are communities where relationships between participating members is formed and maintained through encounters in the online community. For all VOCs, there is the issue of creating identity and reputation in the community. People can create whatever identity they would like to through their interactions with other members. The username is what members identify each other by but it says very little about the person behind it. The main features in online communities that attract people are a shared communication environment, relationships formed and nurtured, a sense of belonging to a group, the internal structure of the group, common space shared by people with similar ideas and interests. The three most critical issues are belonging, identity, and interest. For an online community to flourish there needs to be consistent participation, interest, and motivation.

Research conducted by Helen Wang applied the Technology Acceptance Model to online community participation. Internet self-efficacy positively predicted perceived ease of use. Research found that participants' beliefs in their abilities to use the internet and web-based tools determined how much effort was expected. Community environment positively predicted perceived ease of use and usefulness. Intrinsic motivation positively predicted perceived ease of use, usefulness, and actual use. The technology acceptance model positively predicts how likely it is that an individual will participate in an online community.

Consumer-vendor interaction

Establishing a relationship between the consumer and a seller has become a new science with the emergence of online communities. It is a new market to be tapped by companies and to do so, requires an understanding of the relationships built on online communities. Online communities gather people around common interests and these common interests can include brands, products, and services. Companies not only have a chance to reach a new group of consumers in online communities, but to also tap into information about the consumers. Companies have a chance to learn about the consumers in an environment that they feel a certain amount of anonymity and are thus, more open to allowing a company to see what they really want or are looking for.

In order to establish a relationship with the consumer a company must seek a way to identify with how individuals interact with the community. This is done by understanding the relationships an individual has with an online community. There are six identifiable relationship statuses: considered status, committed status, inactive status, faded status, recognized status, and unrecognized status. Unrecognized status means the consumer is unaware of the online community or has not decided the community to be useful. The recognized status is where a person is aware of the community, but is not entirely involved. A considered status is when a person begins their involvement with the site. The usage at this stage is still very sporadic. The committed status is when a relationship between a person and an online community is established and the person gets fully involved with the community. The inactive status is when an online community has not relevance to a person. The faded status is when a person has begun to fade away from a site. It is important to be able to recognize which group or status the consumer holds, because it might help determine which approach to use.

Companies not only need to understand how a consumer functions within an online community, but also a company "should understand the communality of an online community" This means a company must understand the dynamic and structure of the online community to be able to establish a relationship with the consumer. Online communities have cultures of their own, and to be able to establish a commercial relationship or even engage at all, one must understand the community values and proprieties. It has even been proved beneficial to treat online commercial relationships more as friendships rather than business transactions.

Through online engagement, because of the smoke screen of anonymity, it allows a person to be able to socially interact with strangers in a much more personal way. This personal connection the consumer feels translates to how they want to establish relationships online. They separate what is commercial or spam and what is relational. Relational becomes what they associate with human interaction while commercial is what they associate with digital or non-human interaction. Thus the online community should not be viewed as "merely a sales channel". Instead it should be viewed as a network for establishing interpersonal communications with the consumer.

Growth cycle

See also: Metcalfe's law and Bass diffusion modelMost online communities grow slowly at first, due in part to the fact that the strength of motivation for contributing is usually proportional to the size of the community. As the size of the potential audience increases, so does the attraction of writing and contributing. This, coupled with the fact that organizational culture does not change overnight, means creators can expect slow progress at first with a new virtual community. As more people begin to participate, however, the aforementioned motivations will increase, creating a virtuous cycle in which more participation begets more participation.

Community adoption can be forecast with the Bass diffusion model, originally conceived by Frank Bass to describe the process by which new products get adopted as an interaction between innovative early adopters and those who follow them.

Online learning community

Online learning is a form of online community. The sites are designed to educate. Colleges and universities may offer many of their classes online to their students; this allows each student to take the class at his or her own pace.

According to an article published in volume 21, issue 5 of the European Management Journal titled "Learning in Online Forums", researchers conducted a series of studies about online learning. They found that while good online learning is difficult to plan, it is quite conducive to educational learning. Online learning can bring together a diverse group of people, and although it is asynchronous learning, if the forum is set up using all the best tools and strategies, it can be very effective.

Another study was published in volume 55, issue 1 of Computers and Education and found results supporting the findings of the article mentioned above. The researchers found that motivation, enjoyment, and team contributions on learning outcomes enhanced students learning and that the students felt they learned well with it. A study published in the same journal looks at how social networking can foster individual well-being and develop skills which can improve the learning experience.

These articles look at a variety of different types of online learning. They suggest that online learning can be quite productive and educational if created and maintained properly.

One feature of online communities is that they are not constrained by time thereby giving members the ability to move through periods of high to low activity over a period of time. This dynamic nature maintains a freshness and variety that traditional methods of learning might not have been able to provide.

It appears that online communities such as Misplaced Pages have become a source of professional learning. They are an active learning environment in which learners converse and inquire.

In a study exclusive to teachers in online communities, results showed that membership in online communities provided teachers with a rich source of professional learning that satisfied each member of the community.

Saurabh Tyagi describes benefits of online community learning which include:

- No physical boundaries: Online communities do not limit their membership nor exclude based on where one lives.

- Supports in-class learning: Due to time constraints, discussion boards are more efficient for question & answer sessions than allowing time after lectures to ask questions.

- Build a social and collaborative learning experience: People are best able to learn when they engage, communicate, and collaborate with each other. Online communities create an environment where users can collaborate through social interaction and shared experiences.

- Self-governance: Anyone who can access the internet is self-empowered. The immediate access to information allows users to educate themselves.

These terms are taken from Edudemic, a site about teaching and learning. The article "How to Build Effective Online Learning Communities" provides background information about online communities as well as how to incorporate learning within an online community.

Video "gaming" and online interactions

One of the greatest attractions towards online communities and the role assigned to an online community, is the sense of connection in which users are able to build among other members and associates. Thus, it is typical to reference online communities when regarding the 'gaming' universe. The online video game industry has embraced the concepts of cooperative and diverse gaming in order to provide players with a sense of community or togetherness. Video games have long been seen as a solo endeavor – as a way to escape reality and leave social interaction at the door. Yet, online community networks or talk pages have now allowed forms of connection with other users. These connections offer forms of aid in the games themselves, as well as an overall collaboration and interaction in the network space. For example, a study conducted by Pontus Strimling and Seth Frey found that players would generate their own models of fair "loot" distribution through community interaction if they felt that the model provided by the game itself was insufficient.

The popularity of competitive the online multiplayer games has now even promoted informal social interaction through the use of the recognized communities.

Problems with online gaming communities

As with other online communities, problems do arise when approaching the usages of online communities in the gaming culture, as well as those who are utilizing the spaces for their own agendas. "Gaming culture" offers individuals personal experiences, development of creativity, as well an assemblance of togetherness that potentially resembles formalized social communication techniques. On the other hand, these communities could also include toxicity, online disinhibition, and cyberbullying.

- Toxicity: Toxicity in games usually takes the form of abusive or negative language or behavior.

- Online disinhibition: The utilization in gaming communities to say things that normally would not have been said in an in-person scenario. Offers the individual the access to less restraint ion culturally appropriated interactions, and is typically through the form of aggressiveness. This action is also typically offered through the form of anonymity.

- Dissociative anonymity

- Invisibility

- Power of status and authority

- Cyberbullying: Cyberbullying stems from various levels of degree, but inevitably is cast as abuse and harassment in nature.

Online health community

Online health communities is one example of online communities which is heavily used by internet users. A key benefit of online health communities is providing user access to other users with similar problems or experiences which has a significant impact on the lives of their members. Through people participation, online health communities will be able to offer patients opportunities for emotional support and also will provide them access to experience-based information about particular problem or possible treatment strategies. Even in some studies, it is shown that users find experienced-based information more relevant than information which was prescribed by professionals. Moreover, allowing patients to collaborate anonymously in some of online health communities suggests users a non-judgmental environment to share their problems, knowledge, and experiences. However, recent research has indicated that socioeconomic differences between patients may result in feelings of alienation or exclusion within these communities, even despite attempts to make the environments inclusive.

Problems

Online communities are relatively new and unexplored areas. They promote a whole new community that prior to the Internet was not available. Although they can promote a vast array of positive qualities, such as relationships without regard to race, religion, gender, or geography, they can also lead to multiple problems.

The theory of risk perception, an uncertainty in participating in an online community, is quite common, particularly when in the following online circumstances:

- performances,

- financial,

- opportunity/time,

- safety,

- social,

- psychological loss.

Clay Shirky explains one of these problems like two hoola-hoops. With the emersion of online communities there is a "real life" hoola-hoop and the other and "online life". These two hoops used to be completely separate but now they have swung together and overlap. The problem with this overlap is that there is no distinction anymore between face-to-face interactions and virtual ones; they are one and the same. Shirky illustrates this by explaining a meeting. A group of people will sit in a meeting but they will all be connected into a virtual world also, using online communities such as wiki.

A further problem is identity formation with the ambiguous real-virtual life mix. Identity formation in the real world consisted of "one body, one identity", but the online communities allow you to create "as many electronic personae" as you please. This can lead to identity deception. Claiming to be someone you are not can be problematic with other online community users and for yourself. Creating a false identity can cause confusion and ambivalence about which identity is true.

A lack of trust regarding personal or professional information is problematic with questions of identity or information reciprocity. Often, if information is given to another user of an online community, one expects equal information shared back. However, this may not be the case or the other user may use the information given in harmful ways. The construction of an individual's identity within an online community requires self-presentation. Self-presentation is the act of "writing the self into being", in which a person's identity is formed by what that person says, does, or shows. This also poses a potential problem as such self-representation is open for interpretation as well as misinterpretation. While an individual's online identity can be entirely constructed with a few of his/her own sentences, perceptions of this identity can be entirely misguided and incorrect.

Online communities present the problems of preoccupation, distraction, detachment, and desensitization to an individual, although online support groups exist now. Online communities do present potential risks, and users must remember to be careful and remember that just because an online community feels safe does not mean it necessarily is.

Trolling and harassment

Main article: CyberbullyingCyber bullying, the "use of long-term aggressive, intentional, repetitive acts by one or more individuals, using electronic means, against an almost powerless victim" which has increased in frequency alongside the continued growth of web communities with an Open University study finding 38% of young people had experienced or witnessed cyber bullying. It has received significant media attention due to high-profile incidents such as the death of Amanda Todd who before her death detailed her ordeal on YouTube.

A key feature of such bullying is that it allows victims to be harassed at all times, something not possible typically with physical bullying. This has forced Governments and other organisations to change their typical approach to bullying with the UK Department for Education now issuing advice to schools on how to deal with cyber bullying cases.

The most common problem with online communities tend to be online harassment, meaning threatening or offensive content aimed at known friends or strangers through ways of online technology. Where such posting is done "for the lulz" (that is, for the fun of it), then it is known as trolling. Sometimes trolling is done in order to harm others for the gratification of the person posting. The primary motivation for such posters, known in character theory as "snerts", is the sense of power and exposure it gives them. Online harassment tends to affect adolescents the most due to their risk-taking behavior and decision-making processes. One notable example is that of Natasha MacBryde who was tormented by Sean Duffy, who was later prosecuted. In 2010, Alexis Pilkington, a 17-year-old New Yorker committed suicide. Trolls pounced on her tribute page posting insensitive and hurtful images of nooses and other suicidal symbolism. Four years prior to that an 18-year-old died in a car crash in California. Trolls took images of her disfigured body they found on the internet and used them to torture the girl's grieving parents. Psychological research has shown that anonymity increases unethical behavior through what is called the online disinhibition effect. Many website and online communities have attempted to combat trolling. There has not been a single effective method to discourage anonymity, and arguments exist claiming that removing Internet users' anonymity is an intrusion of their privacy and violates their right to free speech. Julie Zhou, writing for the New York Times, comments that "There's no way to truly rid the Internet of anonymity. After all, names and email addresses can be faked. And in any case many commenters write things that are rude or inflammatory under their real names". Thus, some trolls do not even bother to hide their actions and take pride in their behavior. The rate of reported online harassment has been increasing as there has been a 50% increase in accounts of youth online harassment from the years 2000–2005.

Another form of harassment prevalent online is called flaming. According to a study conducted by Peter J. Moor, flaming is defined as displaying hostility by insulting, swearing or using otherwise offensive language. Flaming can be done in either a group style format (the comments section on YouTube) or in a one-on-one format (private messaging on Facebook). Several studies have shown that flaming is more apparent in computer mediated conversation than in face to face interaction. For example, a study conducted by Kiesler et al. found that people who met online judged each other more harshly than those who met face to face. The study goes on to say that the people who communicated by computer "felt and acted as though the setting was more impersonal, and their behavior was more uninhibited. These findings suggest that computer-mediated communication ... elicits asocial or unregulated behavior".

Unregulated communities are established when online users communicate on a site although there are no mutual terms of usage. There is no regulator. Online interest groups or anonymous blogs are examples of unregulated communities.

Cyberbullying is also prominent online. Cyberbullying is defined as willful and repeated harm inflicted towards another through information technology mediums. Cyberbullying victimization has ascended to the forefront of the public agenda after a number of news stories came out on the topic. For example, Rutgers freshman Tyler Clementi committed suicide in 2010 after his roommate secretly filmed him in an intimate encounter and then streamed the video over the Internet. Numerous states, such as New Jersey, have created and passed laws that do not allow any sort of harassment on, near, or off school grounds that disrupts or interferes with the operation of the school or the rights of other students. In general, sexual and gender-based harassment online has been deemed a significant problem.

Trolling and cyber bullying in online communities are very difficult to stop for several reasons:

- Community members do not wish to violate libertarian ideologies that state everyone has the right to speak.

- The distributed nature of online communities make it difficult for members to come to an agreement.

- Deciding who should moderate and how create difficulty of community management.

An online community is a group of people with common interests who use the Internet (web sites, email, instant messaging, etc.) to communicate, work together and pursue their interests over time.

Hazing

A lesser known problem is hazing within online communities. Members of an elite online community use hazing to display their power, produce inequality, and instill loyalty into newcomers. While online hazing does not inflict physical duress, "the status values of domination and subordination are just as effectively transmitted". Elite members of the in-group may haze by employing derogatory terms to refer to newcomers, using deception or playing mind games, or participating in intimidation, among other activities.

"hrough hazing, established members tell newcomers that they must be able to tolerate a certain level of aggressiveness, grossness, and obnoxiousness in order to fit in and be accepted by the BlueSky community".

Privacy

Online communities like social networking websites have a very unclear distinction between private and public information. For most social networks, users have to give personal information to add to their profiles. Usually, users can control what type of information other people in the online community can access based on the users familiarity with the people or the users level of comfort. These limitations are known as "privacy settings". Privacy settings bring up the question of how privacy settings and terms of service affect the expectation of privacy in social media. After all, the purpose of an online community is to share a common space with one another. Furthermore, it is hard to take legal action when a user feels that his or her privacy has been invaded because he or she technically knew what the online community entailed. Creator of the social networking site Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, noticed a change in users' behavior from when he first initiated Facebook. It seemed that "society's willingness to share has created an environment where privacy concerns are less important to users of social networks today than they were when social networking began". However even though a user might keep his or her personal information private, his or her activity is open to the whole web to access. When a user posts information to a site or comments or responds to information posted by others, social networking sites create a tracking record of the user's activity. Platforms such as Google and Facebook collect massive amounts of this user data through their surveillance infrastructures.

Internet privacy relates to the transmission and storage of a person's data and their right to anonymity whilst online with the UN in 2013 adopting online privacy as a human right by a unanimous vote. Many websites allow users to sign up with a username which need not be their actual name which allows a level of anonymity, in some cases such as the infamous imageboard 4chan users of the site do not need an account to engage with discussions. However, in these cases depending on the detail of information about a person posted it can still be possible to work out a users identity.

Even when a person takes measures to protect their anonymity and privacy revelations by Edward Snowden a former contractor at the Central Intelligence Agency about mass surveillance programs conducted by the US intelligence services involving the mass collection of data on both domestic and international users of popular websites including Facebook and YouTube as well as the collection of information straight from fiber cables without consent appear to show individuals privacy is not always respected. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg publicly stated that the company had not been informed of any such programs and only handed over individual users data when required by law implying that if the allegations are true that the data harvested had been done so without the company's consent.

The growing popularity of social networks where a user using their real name is the norm also brings a new challenge with one survey of 2,303 managers finding 37% investigated candidates social media activity during the hiring process with a study showing 1 in 10 job application rejections for those aged 16 to 34 could be due to social media checks.

Reliability of information

Web communities can be an easy and useful tool to access information. However, the information contained as well as the users' credentials cannot always be trusted, with the internet giving a relatively anonymous medium for some to fraudulently claim anything from their qualifications or where they live to, in rare cases, pretending to be a specific person. Malicious fake accounts created with the aim of defrauding victims out of money has become more high-profile with four men sentenced to between 8 years and 46 weeks for defrauding 12 women out of £250,000 using fake accounts on a dating website. In relation to accuracy one survey based on Misplaced Pages that evaluated 50 articles found that 24% contained inaccuracies, while in most cases the consequence might just be the spread of misinformation in areas such as health the consequences can be far more damaging leading to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration providing help on evaluating health information on the web.

Imbalance

The 1% rule states that within an online community as a rule of thumb only 1% of users actively contribute to creating content. Other variations also exist such as the 1-9-90 rule (1% post and create; 9% share, like, comment; 90% view-only) when taking editing into account. This raises problems for online communities with most users only interested in the information such a community might contain rather than having an interest in actively contributing which can lead to staleness in information and community decline. This has led such communities which rely on user editing of content to promote users into becoming active contributors as well as retention of such existing members through projects such as the Wikimedia Account Creation Improvement Project.

Legal issues

| The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the US, two of the most important laws dealing with legal issues of online communities, especially social networking sites are Section 512c of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

Section 512c removes liability for copyright infringement from sites that let users post content, so long as there is a way by which the copyright owner can request the removal of infringing content. The website may not receive any financial benefit from the infringing activities.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act gives protection from any liability as a result from the publication provided by another party. Common issues include defamation, but many courts have expanded it to include other claims as well.

Online communities of various kinds (social networking sites, blogs, media sharing sites, etc.) are posing new challenges for all levels of law enforcement in combating many kinds of crimes including harassment, identity theft, copyright infringement, etc.

Copyright law is being challenged and debated with the shift in how individuals now disseminate their intellectual property. Individuals come together via online communities in collaborative efforts to create. Many describe current copyright law as being ill-equipped to manage the interests of individuals or groups involved in these collaborative efforts. Some say that these laws may even discourage this kind of production.

Laws governing online behavior pose another challenge to lawmakers in that they must work to enact laws that protect the public without infringing upon their rights to free speech. Perhaps the most talked about issue of this sort is that of cyberbullying. Some scholars call for collaborative efforts between parents, schools, lawmakers, and law enforcement to curtail cyberbullying.

Laws must continually adapt to the ever-changing landscape of social media in all its forms; some legal scholars contend that lawmakers need to take an interdisciplinary approach to creating effective policy whether it is regulatory, for public safety, or otherwise. Experts in the social sciences can shed light on new trends that emerge in the usage of social media by different segments of society (including youths). Armed with this data, lawmakers can write and pass legislation that protect and empower various online community members.

Online Communities during ongoing SARS CoV 2 (COVID 19) Pandemic

When the ongoing Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV 2) otherwise known as COVID 19, pandemic began, online communities and digital space became increasingly important. Since the World Health Organization, other public health agencies, and governments mandated contagion efforts like social distancing and isolation, people needed information and ways to connect with each other. The waves of COVID 19 and the associated dangers and containment measures of the airborne disease led to increased feelings of anxiety, fear, stress, and loneliness. With stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures in place, those with access to social media and digital space were able to find community online. Access to technology is crucial for social interaction and relationship-building.

Online communities during the ongoing COVID 19 pandemic use digital space for three main reasons:

- Education: with schools and universities closed across the globe, most curriculum shifted online.

- Health: with healthcare facilities tending to the global health crisis, many practices use online appointments and meetings.

- Connection: social distancing and isolation containment measures led to people finding community and support online.

Education

Access to digital technology at the beginning of the pandemic became important when students, teachers, and scholars, many of whom had in-person meetings previously, were required to start social distancing or isolate. In order to continue with the education curricula and research plans, those with access to digital devices, used technology to connect to the internet. By using Zoom and other virtual platforms educators, students, and scholars alike were able to maintain social distancing while creating connections to learn about themselves and the world around them. Cairns et al. found in their virtual ethnography that students rely on online technologies to stay connected for school and social engagement activities. Students use a wide variety of technologies including ones for education, entertainment, daily tasks, and social networks and were either synchronous or asynchronous. Online communities are essential for maintaining social connection and educational endeavors.

Health

The ongoing COVID 19 pandemic has led to an increased need for online communities and digital space for those who have preexisting medical conditions or those with post-acute sequelae or long-term health conditions after a SARS CoV 2 infection (Long COVID). Those people who are immunocompromised, disabled, elderly, or have health conditions like cancer, rely on online communities for information, solidarity, and support. Many of them depend on telehealth and social media in order to access healthcare and have connection in a socially-distant reality.

People with these illnesses that place them at risk, have feelings of frustration with the medical and political systems, despair, and grief that are shared within the online health communities. For example, in their article, “Experiences of people affected by cancer during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory qualitative analysis of public online forums,” Colomer-Lahiguera et al. found that cancer survivors and people with cancer had specific concerns with healthcare, infection, logistical and safety measures, and economic impacts that come with job loss and financial burdens. Those with cancer faced challenges in adapting to the “New normal,” social behavioral change, and experiencing cancer. People with cancer also had different needs for advice that were either COVID-related in terms of risk, COVID-19 information, others’ experiences, and measures to take if infected, or Cancer-related such as treatment, managing symptoms and side effects, and suspecting cancer. Online health communities allow for those with heightened fears of infection or reinfection to have the ability to discuss adaptation challenges and strategies to avoid COVID 19. People with cancer and Long COVID are faced with similar challenges in how they access healthcare, how healthcare providers treat them, and how they manage their illness or disease. Online communities offer people with health conditions ways to support each other, learn preventative measures to avoid COVID 19 infections and reinfections, and find shared interests and symptoms.

Connection

Whether they use online communities to connect for educational and research purposes or join to find solidarity or worship, people use the internet to create and foster relationships with others during the ongoing COVID 19 pandemic. In the U.K., Bryson et al. found that virtual faith communities which had online services often created an intrasacred spaces where together physical sacred spaces and rituals with secular become linked together. Congregation members became more active in the faith rituals and preparations than before the pandemic began and the use of social media became an important facilitator of connection. As social creatures, humans crave interaction with one another and people who are social distancing in an effort to avoid COVID 19 infections and reinfections use online communities to find ways of connection.

See also

|

References

- Porter, Constance Elise. (2004). "A Typology of Virtual Communities: A Multi-Disciplinary Foundation for Future Research".

- "Maslow's Hierarchy: Why People Engage in Online Communities". Social Media Today. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Buzzing Communities – How To Build Bigger, Better, And More Active..." FeverBee. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Emma Tracey (July 2013). "What is it like to be blind in Gaza and Israel?". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Diane Coyle; Patrick Meier (2009). "New Technologies in Emergencies and Conflicts: The Role of Information and Social Networks". UN Foundation-Vodafone Foundation Partnership. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Sawyer, Rebecca, "The Impact of New Social Media on Intercultural Adaptation" (2011). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 242. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/242

- "Alexa Top 500 Global Sites". Alexa. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Preece, Jenny; Maloney-Krichmar, Diane (July 2005). "Online Communities: Design, Theory, and Practice". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 10 (4): 00. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00264.x.

- ^ Baym, Nancy. "The new shape of online community: The example of Swedish independent music fandom."

- Jennifer Kyrnin. "Why Create an Online Community". About.com Tech. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011.

- ^ hci.uma.ptPreece03-OnlineCommunities-HandbookChapt.pdf

- Dover, Yaniv; Kelman, Guy (2018). "Emergence of online communities: Empirical evidence and theory". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0205167. arXiv:1711.03574. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305167D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205167. PMC 6333374. PMID 30427835.

- Lawson, M. (January 2014). "Sherlock and Doctor Who: beware of fans influencing the TV they love". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017.

- Kligler-Vilenchik, Neta; McVeigh-Schultz, Joshua; Weitbrecht, Christine; Tokuhama, Chris (2 April 2011). "Experiencing fan activism: Understanding the power of fan activist organizations through members' narratives". Transformative Works and Cultures. 10. doi:10.3983/twc.2012.0322. ISSN 1941-2258.

- Cothrel, Joseph, Williams, L. Ruth "Four Smart Ways to Run Online Communities"

- Johnson, Christopher M (2001). "A survey of current research on online communities of practice". The Internet and Higher Education. 4: 45–60. doi:10.1016/S1096-7516(01)00047-1. S2CID 383368.

- ^ Plant, Robert (January 2004). "Online communities". Technology in Society. 26: 51–65. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2003.10.005.

- "Usage of content management systems for websites". W3Techs. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- "TheBiggestBoards". TheBiggestBoards. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Ami Sedghi (February 2014). "Facebook: 10 years of social networking, in numbers". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "Most used social media 2020". Statista. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- cycles, This text provides general information Statista assumes no liability for the information given being complete or correct Due to varying update; Text, Statistics Can Display More up-to-Date Data Than Referenced in the. "Topic: Social media". Statista. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Number of smartphone social network users in the United States from 2011 to 2017 (in millions)". Statista. 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Brown, Nicole R. (2002). ""Community" Metaphors Online: A Critical and Rhetorical Study Concerning Online Groups". Business Communication Quarterly. 65 (2): 92–100. doi:10.1177/108056990206500210. S2CID 167747541.

- Kim, A.J. (2000). Community Building on the Web : Secret Strategies for Successful Online Communities. Peachpit Press. ISBN 0-201-87484-9

- Shirky, Clay (2008). Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations

- "Worldchanging - Evaluation + Tools + Best Practices: The Worldchanging Interview: Clay Shirky". worldchanging.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- Campbell, J., Fletcher, G. & Greenhil, A. (2002). Tribalism, Conflict and Shape-shifting Identities in Online Communities. In the Proceedings of the 13th Australasia Conference on Information Systems, Melbourne Australia, 7–9 December 2002

- Campbell, John; Fletcher, Gordon; Greenhill, Anita (11 August 2009). "Conflict and identity shape shifting in an online financial community". Information Systems Journal. 19 (5): 461–478. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2008.00301.x. ISSN 1350-1917 – via John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Gruzd, Anatoliy, Barry Wellman, and Yuri Takhteyev. "Imagining Twitter as an Imagined Community." American Behavioral Scientist (2011). Print.

- ^ Andrews, Dorine C. (April 2001). "Audience specific online-community design". Communications of the ACM. 45 (4): 64–68. doi:10.1145/505248.505275. S2CID 14359484.

- Nonnecke, Blair; Dorine Andrews; Jenny Preece (2006). "Non-public and public online community participation: Needs, attitudes and behavior". Electronic Commerce Research. 6 (1): 7–20. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.457.5320. doi:10.1007/s10660-006-5985-x. S2CID 21006597.

- Zhou, Tao (28 January 2011). "Understanding online community user participation: a social influence perspective". Internet Research. 21 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1108/10662241111104884. S2CID 15351993.

- Ridings, Catherine M.; David Gefen (2006). "Virtual Community Attraction: Why People Hang Out Online". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 10 (1): 00. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00229.x. S2CID 21854835.

- ^ Horrigan, John Bernard (31 October 2001). "The vibrant social universe online" (PDF). Online Communities: Networks that nurture long-distance relationships and local ties. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. pp. 2–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- "What Is An Online Community?". Social Media Today. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012.

- Armstrong, A.; Hagel, J. (1996). "The real value of on-line communities". Harvard Business Review. 74 (3): 134–141.

- Choudhury, Anubhav (2012). incrediblogger

- "Lave and Wenger". What is an online community?>Virtual Community online community or e-community>Membership life cycle>. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Arguello, Jaime; Butler, Brian S.; Joyce, Lisa; Kraut, Robert; Ling, Kimberly S.; Wang, Xiaoqing (2006). "Talk to me". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in computing systems - CHI '06. p. 959. doi:10.1145/1124772.1124916. ISBN 1595933727. S2CID 6638329.

- Steinmacher, Igor; Silva, Marco Aurelio Graciotto; Gerosa, Marco Aurelio (2015). "A systematic literature review on the barriers faced by newcomers to open source software projects". Information and Software Technology. 59: 67–85. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2014.11.001. S2CID 15284278.

- Kraut, Robert (2016). Building Successful Online Communities: Evidence-Based Social Design. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262528917.

- Halfaker, Aaron; Kittur, Aniket; Riedl, John (2011). "Don't bite the newbies". Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Wikis and Open Collaboration - Wiki Sym '11. p. 163. doi:10.1145/2038558.2038585. ISBN 9781450309097. S2CID 2818300.

- Bauer, Talya N.; Bodner, Todd; Erdogan, Berrin; Truxillo, Donald M.; Tucker, Jennifer S. (2007). "Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods". Journal of Applied Psychology. 92 (3): 707–721. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1015.5132. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.707. PMID 17484552. S2CID 9724228.

- Zube, Paul; Velasquez, Alcides; Ozkaya, Elif; Lampe, Cliff; Obar, Jonathan (2012). Classroom Misplaced Pages participation effects on future intentions to contribute. Proceedings of the ACM 2012 conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work - CSCW '12. p. 403. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145267. ISBN 9781450310864.

- Cosley, D., Frankowski, D., Ludford, P.J., & Terveen, L. (2004). Think different: increasing online community participation using uniqueness and group dissimilarity. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the sigchi conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 631–638). New York, NY: ACM.

- Ardichvili, Alexander; Page, Vaughn; Wentling, Tim (March 2003). "Motivation and barriers to participation in virtual knowledge-sharing communities of practice" (PDF). Journal of Knowledge Management. 7 (1): 64–77. doi:10.1108/13673270310463626. S2CID 14849211. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2017.

- Bernstein, M. S.; Bakshy, E.; Burke, M.; Karrer, B. (April 2013). "Quantifying the invisible audience in social networks" (PDF). Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM. pp. 21–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Budiman, Adrian M. (2008). Virtual Online Communities: A Study of Internet Based Community Interactions (PhD dissertation). Ohio University. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022.

- Stefano Tardini (January 2005). "A semiotic approach to online communities: belonging, interest and identity in websites' and videogames' communities". Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- Wang, H., et al. (2012). "Understanding Online Community Participation: A Technology Acceptance Perspective." Communication Research 39(6): 781–801.

- ^ Heinonen, Kristina (2011). "Conceptualizing consumers' dynamic relationship engagement: the development of online community relationships". Journal of Customer Behaviour. 10 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1362/147539211X570519.

- Goodwin, C. (1996). "Communality as a dimension of service relationships". Journal of Consumer Psychology. 5 (4): 387–415. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp0504_04.

- Heinonen, K.; Strandvik, T.; Mickelsson, K-J.; Edvardsson, B.; Sundström, E. & Andersson, P. (2010). "A Customer Dominant Logic of Service". Journal of Service Management. 21 (4): 531–548. doi:10.1108/09564231011066088.

- Gerardine Desanctis; Anne Laure Fayard; Michael Roach; Lu Jiang (2003). "Learning in Online Forums" (PDF). European Management Journal. 21 (5): 565–577. doi:10.1016/S0263-2373(03)00106-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2011.

- Elizabeth Avery Gomeza; Dezhi Wub; Katia Passerinic (August 2010). "Computer-supported team-based learning". Computers & Education. 55 (1): 378–390. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.003.

- Yu, Angela Yan; Tian, Stella Wen; Vogel, Douglas; Chi-Wai Kwok, Ron (December 2010). "Can learning be virtually boosted? An investigation of online social networking impacts". Computers & Education. 55 (4): 1494–1503. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2010.06.015.

- ^ Saurabh Tyagi (6 October 2013). "How to Build Effective Online Learning Communities". Archived from the original on 7 October 2013.

- Strimling, Pontus; Frey, Seth (2020). "Emergent Cultural Differences in Online Communities' Norms of Fairness". Games and Culture. 15 (4): 394–410. doi:10.1177/1555412018800650. S2CID 149482590.

- Kishonna L. Gray (2012) INTERSECTING OPPRESSIONS AND ONLINE COMMUNITIES, Information, Communication & Society, 15:3, 411-428, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.642401

- Seay, A. F., Jerome, W. J., Lee, K. S. & Kraut, R. E. (2004) 'Project massive: a study of online gaming communities', inProceedings of CHI 2004, ACM, New York, pp. 1421–1424.

- Suler, J. (2004) 'The online disinhibition effect', Cyber Psychology and Behavior, vol.7, no. 3, pp. 321–326.

- Joinson, A. (2001) 'Self-disclosure in computer mediated communication: The roleof self-awareness and visual anonymity', European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 31, pp. 177–192.

- ^ Neal, Lisa; et al. (2007). Online health communities. CHI'07 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM.

- Chou, Wen-ying Sylvia; et al. (2009). "Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 11 (4): e48. doi:10.2196/jmir.1249. PMC 2802563. PMID 19945947.

- Chou, Wen-ying Sylvia; et al. (2011). "Health-related Internet use among cancer survivors: data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003–2008". Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 5 (3): 263–70. doi:10.1007/s11764-011-0179-5. PMID 21505861. S2CID 38009353.

- ^ Russell, David; Spence, Naomi J.; Chase, Jo-Ana D.; Schwartz, Tatum; Tumminello, Christa M.; Bouldin, Erin (December 2022). "Support amid uncertainty: Long COVID illness experiences and the role of online communities". Qualitative Research in Health. 2. doi:10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100177. PMC 9531408. PMID 36212783.