| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Kaitai Shinsho" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

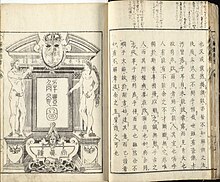

Kaitai Shinsho (解体新書, Kyūjitai: 解體新書, roughly meaning "New Text on Anatomy") is a medical text translated into Japanese during the Edo period. It was written by Sugita Genpaku, and was published by Suharaya Ichibee (須原屋市兵衛) in 1774, the third year of An'ei. The body comprises four volumes, the illustrations, one. The contents are written kanbun-style. It is based on the Dutch-language translation Ontleedkundige Tafelen, often known in Japan as Tafel Anatomie (ターヘル・アナトミア, Tāheru Anatomia), of Johann Adam Kulmus’ Latin Tabulae Anatomicae, published before 1722 (exact year is unknown) in Gdańsk, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. As a full-blown translation from a Western language, it was the first of its kind in Japan.

Background

On 4 March 1771, the eighth year of Meiwa, the students of Rangaku medicine Sugita Genpaku, Maeno Ryōtaku, Nakagawa Jun'an, et al., by studying performing autopsies on criminals executed at the Kozukappara execution grounds (now, there is a possibility that Katsuragawa Hoshū was at this facility as well, but from the description in Rangaku Koto Hajime (蘭学事始), it seems more likely that he was not). Both Sugita and Maeno had the book Ontleedkundige Tafelen, imported from Holland. Sugita, marveling at the accuracy of the work while comparing it by eye with his autopsies, proposed to Maeno that it be translated. For some time, Sugita had a desire to translate something from Dutch; now he would get approval for this. He met with Maeno the very next day (5 March) and began translation. The one who recommended Kaitai Shinsho to the shōgun was Katsuragawa Hosan.

At first, Sugita and Nakagawa could not actually read Dutch; even with Maeno who could, their Dutch vocabulary was inadequate. It would have been difficult for them to consult with the Dutch translations and translators (Tsūji) in Nagasaki, and naturally there were no dictionaries at the time. A translation from any other Western language would have been out of the question, as the government of the time did not allow contact with any other Western nation. Therefore, in a process comparable to cryptanalysis, they progressed with translation work. In his later years, Sugita would detail the process in Rangaku Koto Hajime.

In the second year of An'ei (1773), as they arrived at a translation goal, in order to ascertain society's and above all the authorities' response, they released the "Anatomical Diagrams" (解体約図, Kaitai Yakuzu), a five-page flyer.

In 1774, Kaitai Shinsho was published.

Influences

Maeno Ryōtaku was at the center of the translation work, but his name is only mentioned in the dedication written by the famous interpreter Yoshio Kōsaku. By one account, Maeno was on the way to study at Nagasaki; when he prayed at a Tenman-gū for the fulfillment of his studies, he vowed not to study in order to raise his own name, so he abstained from submitting it. By another account, since he knew that the completed works were not completely perfect, the academic Maeno could not submit his name in good conscience. Sugita Genpaku said, "I am sickly and numbered in years as well. I do not know when I will die." While he knew the translation was imperfect in places, he rushed to publish. The publication of "Anatomic Illustrations" was also Sugita's design; in regard to this, Maeno is said to have had shown dislike for it. However, the man would actually go on to live an extremely long life for the time (he lived to the age of eighty-five). Unsure of when he would die and unsure of whether the government would approve the distribution of the Western ideas, it could be said this was a risky but important move.

Nakagawa Jun'an, after Kaitai Shinsho’s publication, also continued his study of Dutch, along with Katsuragawa Hoshū, and took on the natural history of Sweden according to Thunberg. Katsuragawa Hosan was a same-generation friend of Sugita's. With his status as a hōgen, he served as a court physician to the shōgun. He was not a direct influence on the translation work itself, though his son Hoshū did participate. Also, he provided for the supplementary materials that amounted to three volumes of Dutch medical texts. Upon the publishing of Kaitai Shinsho, since there was a possibility that it encroached on the Bakufu's taboos, Katsuragawa was the one who ran it by the Ōoku. Katsuragawa Hoshū was the son of the hōgen Katsuragawa Hosan, and would become a hōgen himself later on. He is said to have been involved with the translation work from early on. Afterwards, he would serve to develop rangaku along with Ōtsuki Gentaku.

There are others that had to do with the translation work, like Ishikawa Genjō, whose name appears in the opening pages, Toriyama Shōen, Kiriyama Shōtetsu, and Mine Shuntai (among others) whose names appear in Rangaku Koto Hajime. Yoshio Kōgyū (posthumously Yoshio Nagaaki) was a Dutch tsūji. He wrote the preface to Kaitai Shinsho, and admired what he felt to be Sugita and Maeno's masterpiece. Hiraga Gennai, on Shōgatsu of the third year of An'ei, visited the home of Sugita Genpaku. The translation of Kaitai Shinsho’s text was nearly complete, and he was informed that they were looking for an artist for the dissection figures. Odano Naotake was a bushi from Kakunodate in the Akita Domain, and the artist. By Hiraga Gennai's referral, he got to drawing Kaitai Shinsho's figures off the original pictures. Until Kaitai Shinsho's first edition, it took the short time of half a year. It was his first time working in Edo, and yet it was historical record-setting work for Japanese science.

Content

Kaitai Shinsho is generally said to be a translation of Ontleedkundige Tafelen. However, other than the work itself, Bartholini's, Blankaart's, Schamberger’s, Koyter’s, Veslingius', Palfijn's, and others' works were also consulted; the cover is based on Valuerda's. Of course, Asian sources and opinions also had an influence.

The book is not a mere translation; the translation was done mostly by Maeno Ryōtaku and then transponed into classical Chinese by Sugita. There are notes in various places left by Sugita, as leftovers from the work. All those lengthy footnotes that cover more than 50% of Kulmus' book were left out.

The contents are split into four volumes:

- Volume I

- General remarks; forms and names; parts of the body; skeletal structure: general remarks about joints; skeletal structure: detailed exposition about joints.

- Volume II

- The head; the mouth; the brain and nerves; the eyes; the ears; the nose; the tongue.

- Volume III

- The chest and the diaphragm; the lungs; the heart; arteries; veins; the portal vein; the abdomen; the bowels and stomach; the mesentery and lacteals; the pancreas.

- Volume IV

- The spleen; the liver and gall bladder; the kidneys and the bladder; the genitalia; pregnancy; the muscles.

The illustrations only comprise one volume.

Effect afterwards

After the publication of the Kaitai Shinsho, there was besides the development in medical science, the progress of the comprehension of the Dutch language. Also, it is important to note that Japan, even under its extreme isolationist policies, still had some foundation to understand the products of Western culture. It also helped to give a chance for promotion for such talents as those of Ōtsuki Gentaku.

In translation, some words had to be coined (that is, there were no Japanese words that existed for them prior to the work). Some of them, such as the terms for "nerve" (神経, shinkei), "cartilage" (軟骨, nankotsu), and "artery" (動脈, dōmyaku) are still used to this day as a result. A great number of anatomical terms were transliterated using Chinese characters. They disappeared quickly during the following decades.

The fact that this was a first translation means that misunderstandings were practically unavoidable. There are many mistranslations in the Kaitai Shinsho; later on, Ōtsuki Gentaku retranslated it and released the Authoritative and Revised New Text on Anatomy (重訂解体新書, Chōtei Kaitai Shinsho) in the ninth year of Bunsei (1826).

In his last years, Sugita Genpaku would write about the work on Kaitai Shinsho in The Beginnings of Rangaku (蘭学事始, Rangaku Koto Hajime). This text had a great influence on writings about the modernization of Japanese medicine.

See also

- Sugita Genpaku

- Nakagawa Jun'an

- Satake Shozan

- Hiraga Gennai

- Kaitai-Shin Show (an educational program on NHK)

References

| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (November 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Ontleedkundige tafelen, benevens de daar toe behoorende afbeeldingen en aanmerkingen, waarin het zaamenstel des menschelyken lichaams, en het gebruik van alle des zelfs deelen, afgebeeld en geleerd word, door Johan Adam Kulmus, ... In het Neederduitsch gebragt door Gerardus Dicten, chirurgyn te Leyden. Te Amsterdam, by de Janssoons van Waesberge, 1734.

- Szarszewski, Adam (2009). "Johann Adam Kulmus, "Tabulae Anatomicae", Gdańsk 1722 – Sugita Genpaku, "Kaitai Shinsho", Edo 1774". Annales Academiae Medicae Gedanensis (39): 133–144. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Screech, Timon and Carl Peter Thunberg. Japan Extolled and Decried: Carl Peter Thunberg and the Shogun's Realm, 2005. ISBN 0-7007-1719-6.

- Takashina Shūji, Yōrō Takeshi, Haga Tōru, et al. Present Day in the middle of Edo – Akita Dutch Pictures and "Kaitai Shinsho", 1996. ISBN 4-480-85729-X.

External links

- Johann Adam Kulmus. Kaitai shinsho. Illustrations from the original text. Historical Anatomies on the Web, National Library of Medicine.

- (in Japanese) Kaitai Shinsho