| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Lune" geometry – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

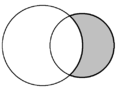

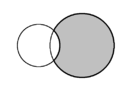

| In plane geometry, the crescent shape formed by two intersecting circles is called a lune. In each diagram, two lunes are present, and one is shaded in grey. | ||

In plane geometry, a lune (from Latin luna 'moon') is the concave-convex region bounded by two circular arcs. It has one boundary portion for which the connecting segment of any two nearby points moves outside the region and another boundary portion for which the connecting segment of any two nearby points lies entirely inside the region. A convex-convex region is termed a lens.

Formally, a lune is the relative complement of one disk in another (where they intersect but neither is a subset of the other). Alternatively, if and are disks, then is a lune.

Squaring the lune

In the 5th century BC, Hippocrates of Chios showed that the Lune of Hippocrates and two other lunes could be exactly squared (converted into a square having the same area) by straightedge and compass. Around 1000, Alhazen attempted to square a circle using a pair of lunes now bearing his name. In 1766 the Finnish mathematician Daniel Wijnquist, quoting Daniel Bernoulli, listed all five geometrical squareable lunes, adding to those known by Hippocrates. In 1771 Leonhard Euler gave a general approach and obtained a certain equation to the problem. In 1933 and 1947 it was proven by Nikolai Chebotaryov and his student Anatoly Dorodnov that these five are the only squarable lunes.

Area

The area of a lune formed by circles of radii a and b (b>a) with distance c between their centers is

where is the inverse function of the secant function, and where

is the area of a triangle with sides a, b and c.

See also

References

- ^ A history of analysis. H. N. Jahnke. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. 2003. p. 17. ISBN 0-8218-2623-9. OCLC 51607350.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Google Groups". Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Lune". MathWorld.

External links

- The Five Squarable Lunes at MathPages

and

and  are disks, then

are disks, then  is a lune.

is a lune.

is the

is the