| Lycosuchidae Temporal range: Middle Permian, 265–260 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Partial skull of Lycosuchus in the Museum für Naturkunde, with "double canines" visible | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Therocephalia |

| Family: | †Lycosuchidae Nopcsa, 1923 |

| Valid genera | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Lycosuchidae is an extinct family of therocephalian therapsids from the Middle Permian Beaufort Group of South Africa. It currently includes only two monospecific genera, Lycosuchus, represented by L. vanderrieti, which was named by paleontologist Robert Broom in 1903, and Simorhinella, represented by S. baini, which was named by Broom in 1915. Both species are characterized by their large size, reduced tooth counts and short, relatively low and broad snouts.

Two sets of functional enlarged canine teeth, so-called "double canines", were once regarded as a defining feature of lycosuchids. However, recent studies have proposed that they actually represent co-existing functional and replacement canines, and various lycosuchid specimens show the teeth at different stages of growth and replacement. Nonetheless, the pattern of tooth replacement appears to be unusual in lycosuchids, and the alternating canines appear to occur concurrently more than in other predatory therapsid groups. Lycosuchids are among the earliest known therocephalians and are also thought to be the most basal. The Russian genus Gorynychus, containing two species, may also belong to the family, although this result is not typically recovered.

Taxonomy and classification

The concept of a family of "double canined" early therocephalians was first initiated by Broom in 1908, when he proposed that the "double canined" early therocephalians formed a separate unit from other early therocephalians then recognised as the "Pristerognathidae" (now known as Scylacosauridae). Broom would continue to postulate that such a division existed, but for many decades he did not attribute a name to such a group despite Lycosuchidae already being made available. The family Lycosuchidae was first established by Baron Franz Nopcsa in 1923, although the name was often misattributed by later researchers until the end of the 20th century when his precedent was recognised. A Lycosuchidae family was also used by Samuel W. Williston in his 1925 publication The Osteology of the Reptiles, and a similar concept was used by Haughton and Brink in 1954, though neither of them attributed any authorship to Lycosuchidae.

The validity of Lycosuchidae was not always supported by researchers, particularly when simultaneous functional canines were the only proposed criterion. This culminated in a paper by Juri van den Heever in 1980, where he argued that lycosuchids were an unnatural, artificial collection of "pristerognathids" that had died during the process of alternating canine replacement typical of predatory therapsids, and argued it should be invalidated. When not recognised as forming their own family, lycosuchid genera were typically subsumed under the family Scylacosauridae, which was more commonly (though incorrectly) identified as Pristerognathidae by most researchers during the 20th century. Van den Heever would later reconsider his view on lycosuchids and recognise them as a distinct lineage after all, establishing the anatomical criteria for which the family is diagnosed today.

An alternate name for the family, Trochosuchidae, was established by Alfred Romer in 1956, apparently unaware of the pre-existing use of Lycosuchidae by other authors. Romer named the family after Trochosuchus, a now dubious genus of lycosuchid. Curiously, Romer would erect a family for the lycosuchid genera for a second time in 1966, this time as Trochosauridae after the lycosuchid Trochosaurus (also now dubious). Romer likely did this because in 1966 he felt that Trochosuchus was distinct from lycosuchids and so assigned it to another family, the Alopecodontidae (a family otherwise made up of what are now scylacosaurids). This is despite the fact that Romer had previously considered the genera Trochosuchus and Trochosaurus synonymous while under Trochosuchidae. Although Lycosuchidae has priority over either name, some authors perpetuated the use of Trochosuchidae and Trochosauridae, including some who used the former well after Romer proposed replacing it with Trochosauridae (e.g. Camp et al. (1968, 1972)).

Dubious genera

Although now only containing two definitive members, a number of other genera have historically been assigned to Lycosuchidae (or its equivalent grouping by the author). However, all other genera besides Lycosuchus that have been historically included in Lycosuchidae are now regarded as nomen dubia, or dubious names. These include the aforementioned Trochosuchus and Trochosaurus, as well as Hyaenasuchus, Trochorhinus and Zinnosaurus. As such, the majority of specimens attributed to Lycosuchidae are incertae sedis, with only a few being attributable to diagnosable taxa.

The dubiousness of all other historically named lycosuchids is in part due to the often poor quality of their type material, which are often incomplete and badly weathered. Another confounding factor is that several were distinguished based on features such as the proportions of the canines snout, and number of postcanine teeth—features now known to be variable and subject to taphonomic distortion—as is the case for Trochosuchus, Trochosaurus and Trochorhinus. Also, the only other valid lycosuchid genus, Simorhinella, is only distinguished from Lycosuchus by features of its palate. As such, other lycosuchids cannot be identified to a genus if the palate is obscured, as it is in the holotypes of Hyenasuchus and Zinnosaurus.

While the genus was never explicitly assigned to Lycosuchidae, two species of the dubious basal therocephalian Scymnosaurus, S. ferox (the type) and S. major, are also based upon lycosuchid material and so it could also be regarded as an additional dubious lycosuchid.

Phylogeny

An early phylogenetic hypothesis for lycosuchids was proposed by Broom in 1908 before the family had even been established. In it, Broom hypothesised that genera that would later become lycosuchids were one of several lines of descent from a primitive therocephalian common ancestor, namely Alopecodon. From this ancestor, Broom traced a direct line of descent from Hyaenasuchus, to Trochosuchus and finally into Lycosuchus. This line of descent was based upon their dentition, beginning with the aqcquisition of two supposed functional large canines in Hyaenasuchus, followed by a decrease in the number of incisors in Trochosuchus and finally to the loss of most postcanines in Lycosuchus.

Following the taxonomic work of Van den Heever in the 1980s, Lycosuchidae become functionally monotypic and subsequently phylogenetic analyses have only ever included Lycosuchus to represent the group. As such, with only one taxon to include, it is difficult to assess whether Lycosuchidae as recognised (including the various specimens attributed to it) definitively forms a clade. For example, the first cladistic analysis of therocephalians by Hopson and Barghusen (1986) simply subsumed Lycosuchus into Pristerognathidae (=Scylacosauridae) as a single family of early therocephalians. Nonetheless, a revision of Scylacosauridae in 2023 by Christian F. Kammerer has explicitly defined Scylacosauridae to exclude Lycosuchus.

Although Simorhinella has also been regarded as a lycosuchid since 2014, it has yet to be included in a phylogenetic analysis to test the family's potential monophyly. Notably, Abdala et al. (2014) highlight that while Simorhinella possesses the diagnostic characteristics of Lycosuchidae, it also has several traits in its palate found in scylacosaurids but not seen in Lycosuchus. This raises the possibility that Lycosuchidae is paraphyletic relative to scylacosaurian therocephalians (Scylacosauridae + Eutherocephalia), with Simorhinella potentially closer to Scylacosauria.

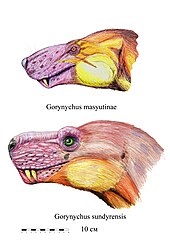

On the other hand, the Russian therocepalian Gorynychus was recovered as the sister taxon of Lycosuchus by Liu and Abdala (2019), effectively in a monophyletic Lycosuchidae (shown below, left). However, this result was only recovered under the majority rule consensus (i.e. it was not recovered in every iteration of the analysis), and it has only been recovered once since then. Indeed, most subsequent analyses of this dataset (such as Liu and Abdala, 2023, below right cladogram) have found Gorynychus to be placed intermediately between Lycosuchus and Scylacosauria (as would be the suggested position of Simorhinella). Gorynychus was also assigned to Lycosuchidae by Suchkova and Golubev (2018), independently of these phylogenetic results, when they named G. sundyrensis. However, this was based entirely on anatomical similarities and was not supported by any phylogenetic analysis.

|

Liu & Abdala (2019):

|

Liu & Abdala (2023):

|

Note that in both cladograms, regardless of the placement of Gorynychus, Lycosuchus occupies a basalmost position in Therocephalia. This result has been consistently recovered in most phylogenetic analyses of therocephalian relationships, while scylacosaurids are closer to Eutherocephalia. Contrary to these results, a recent analysis from 2024 with the aim of analysing the relationships of early cynodonts and therocephalians found a paraphyletic Therocephalia in which Lycosuchus and Alopecognathus (representing scylacosaurids) were instead sister taxa, forming a clade that was itself the sister of Eutherocephalia + Cynodontia.

|

Traditional therocephalians |

References

- ^ Abdala, F.; Kammerer, C. F.; Day, M. O.; Jirah, S.; Rubidge, B. S. (2014). "Adult morphology of the therocephalian Simorhinella bainifrom the middle Permian of South Africa and the taxonomy, paleobiogeography, and temporal distribution of the Lycosuchidae". Journal of Paleontology. 88 (6): 1139. doi:10.1666/13-186.

- ^ Kammerer, C. E. (2023). "Revision of the Scylacosauridae (Therapsida: Therocephalia)". Palaeontologia africana. 56: 51–87. ISSN 2410-4418.

- ^ Broom, R. (1908). "On the inter-relationships of the known Therocephalian genera". Annals of the South African Museum. 4: 369–372.

- ^ Van den Heever, J. A. (1980). "On the validity of the therocephalian family Lycosuchidae (Reptilia, Therapsida)". Annals of the South African Museum. 81: 111–125.

- ^ Van den Heever, J. (1987). The comparative and functional cranial morphology of the early Therocephalia (Amniota: Therapsida) (Ph.D. thesis). University of Stellenbosch.

- Van Den Hever, J. A. (1994). "The cranial anatomy of the early Therocephalia (Amniota: Therapsida)". Annals of the University of Stellenbosch. 1: 1–59.

- Romer, Alfred S. (1956). Osteology of the Reptiles. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-89464-985-1.

- Romer, Alfred S. (1966). Vertebrate Paleontology (Third ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-7167-1822-2.

- Wyllie, Alistair (2003). "A review of Robert Broom's therapsid holotypes: have they survived the test of time" (PDF). Palaeontologia africana. 39: 1–19 – via CORE.

- ^ Liu, Jun; Abdala, Fernando (2019-02-22). "The tetrapod fauna of the upper Permian Naobaogou Formation of China: 3. Jiufengia jiai gen. et sp. nov., a large akidnognathid therocephalian". PeerJ. 7: e6463. doi:10.7717/peerj.6463. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6388668. PMID 30809450.

- ^ Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2023). "Late Permian terrestrial faunal connections invigorated: the first whaitsioid therocephalian from China". Palaeontologia africana. 56: 16–35. hdl:10539/35706.

- Suchkova, J.A.; Golubev, V.K. (2019). "New Permian therocephalian (Therocephalia, Theromorpha) from the Sundyr Assemblage of Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal (4): 87–92. doi:10.1134/S0031031X19040123.

- Pusch, L. C.; Kammerer, C. F.; Fröbisch, J. (2024). "The origin and evolution of Cynodontia (Synapsida, Therapsida): Reassessment of the phylogeny and systematics of the earliest members of this clade using 3D-imaging technologies". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25394. PMID 38444024.

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Lycosuchidae | |