| Mexican wolf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captive Mexican wolf running at Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico | |

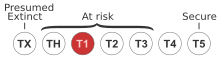

| Conservation status | |

Critically Imperiled (NatureServe) | |

Endangered (ESA) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus |

| Subspecies: | C. l. baileyi |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus baileyi (Nelson & Goldman, 1929) | |

| |

| C. l. baileyi range in 2023 | |

The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), also known as the lobo mexicano (or, simply, lobo) is a subspecies of gray wolf (C. lupus) native to eastern and southeastern Arizona and western and southern New Mexico (in the United States) and fragmented areas of northern Mexico. Historically, the subspecies ranged from eastern Southern California south into Baja California, east through the Sonora and Chihuahua Deserts and into West Texas.

Its ancestors were likely among the first gray wolves to enter North America after the extinction of the Ice Age's Beringian wolf, as indicated by its southern range and basal physical and genetic characteristics. Though once held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico, Canis lupus baileyi became the most endangered gray wolf subspecies in North America, having been extirpated in the wild during the mid-1900s through a combination of hunting, trapping, poisoning and the removal of pups from dens, mainly out of fear, by livestock herders and ranch owners. After being listed officially under the Endangered Species Act in 1976, both the United States and Mexico collaborated to capture all lobos remaining in the wild. This extreme preventative measure would end up forestalling their imminent extinction; five wild Mexican wolves (four males and one pregnant female) were captured, alive, in Mexico between 1977 and 1980. Once settled in captive rescue centers, this group of wolves would prove vital in starting a captive breeding program. Thanks to these preemptive measures, captive-bred Mexican wolves were released into recovery areas in Arizona and New Mexico beginning in 1998 in an effort to recolonize the animals' historical range.

As of 2024, there are at least 257 wild Mexican wolves in the US and 45 in Mexico, and 380 in captive breeding programs, up from the 11 individuals that were released in Arizona in 1998. The year 2021 was the most successful so far for the recovery program, as the highest number of individuals were counted, the most pups were born and survived, and the highest number of wolf packs. Approximately 60% of the lobos that year were found in New Mexico, and 40% in Arizona; historically, both states have had similar numbers of wolves. In 2021, the U.S. population had nearly doubled over a five-year span. These numbers represent a minimum as the survey only counts wolf sightings confirmed by Interagency Field Team staff.

Description

The Mexican wolf is the smallest of North America's gray wolf subspecies, weighing 50–80 lb (23–36 kg) with an average height of 28–32 in (710–810 mm) and an average length of 5.5 ft (1.7 m). It is similar to the Great Plains wolf (C. l. nubilus), albeit distinguishable by a smaller, narrower skull and darker, more variable pelage.

Taxonomy

The Mexican wolf was first described as a distinct subspecies in 1929 by Edward Nelson and Edward Goldman on account of its small size, narrow skull and dark pelt. This wolf is recognized as a subspecies of Canis lupus in the taxonomic authority Mammal Species of the World (2005). In 2019, a literature review of previous studies was undertaken by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The position of the National Academies is that the historic population of Mexican wolf represents a distinct evolutionary lineage of gray wolf, and that modern Mexican wolves are their direct descendants. It is a valid taxonomic subspecies classified as Canis lupus baileyi.

Lineage

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) migrated from Eurasia into North America 70,000–23,000 years ago and gave rise to at least two morphologically and genetically distinct groups. One group is represented by the extinct Beringian wolf and the other by the modern populations. One author proposes that the Mexican wolf's ancestors were likely the first gray wolves to cross the Bering Land Bridge into North America during the Late Pleistocene after the extinction of the Beringian wolf, colonizing most of the continent until pushed southwards by the newly arrived ancestors of the Great Plains wolf (C. l. nubilus).

A haplotype is a group of genes found in an organism that are inherited together from one of their parents. Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years. A 2005 study compared the mitochondrial DNA sequences of modern wolves with those from thirty-four specimens dated between 1856 and 1915. The historic population was found to possess twice the genetic diversity of modern wolves, which suggests that the mDNA diversity of the wolves eradicated from the western US was more than twice that of the modern population. Some haplotypes possessed by the Mexican wolf, the Great Plains wolf, and the extinct Southern Rocky Mountain wolf were found to form a unique "southern clade". All North American wolves group together with those from Eurasia, except for the southern clade which form a group exclusive to North America. The wide distribution area of the southern clade indicates that gene flow was extensive across the recognized limits of its subspecies.

In 2016, a study of mitochondrial DNA sequences of both modern and ancient wolves generated a phylogenetic tree which indicated that the two most basal North American haplotypes included the Mexican wolf and the Vancouver Island wolf.

In 2018, a study looked at the limb morphology of modern and fossil North American wolves. The major limb bones of the dire wolf, Beringian wolf, and most modern North American gray wolves can be clearly distinguished from one another. Late Pleistocene wolves on both sides of the Laurentide Ice Sheet — Cordilleran Ice Sheet possessed shorter legs when compared with most modern wolves. The Late Pleistocene wolves from the Natural Trap Cave, Wyoming and Rancho La Brea, southern California were similar in limb morphology to the Beringian wolves of Alaska. Modern wolves in the Midwestern US and northwestern North America possess longer legs that evolved during the Holocene, possibly driven by the loss of slower prey. However, shorter legs survived well into the Holocene after the extinction of much of the Pleistocene megafauna, including the Beringian wolf. Holocene wolves from Middle Butte Cave (dated less than 7,600 YBP) and Moonshiner Cave (dated over 3,000 YBP) in Bingham County, Idaho were similar to the Beringian wolves. The Mexican wolf and pre-1900 samples of the Great Plains wolf resembled the Late Pleistocene and Holocene fossil gray wolves due to their shorter legs.

Ancestor

In 2021, a mitochondrial DNA analysis of North American wolf-like canines indicates that the extinct Late Pleistocene Beringian wolf was the ancestor of the southern wolf clade, which includes the Mexican wolf and the Great Plains wolf. The Mexican wolf is the most basal of the gray wolves that live in North America today.

Hybridization with coyotes and other wolves

Multiple recent studies using morphological (skull measurements) and genetic datasets have concluded that Mexican wolves hybridized in clinal fashion with other wolf subspecies where both met. The Mexican Wolf Recovery plan (2017, First Revision) currently plans to manage against such occurrence in the event that Northern Rockies and Mexican wolves come into contact to protect against a genetic swamp (i.e. genes of one group become dominant and thus result in loss of genes of another group). While the purity of Mexican wolf DNA composition is important for the time being, a natural, free-ranging wolf population on a continental scale would include hybridization between different subspecies to occur freely. Mexican wolves are under considerable threat from low genetic diversity and inbreeding because all wild Mexican wolves share on average the same amount of genes as full siblings do (all present day wild wolves are descendants of an original seven, called founders).

Unlike eastern wolves and red wolves, the gray wolf species rarely interbreeds with coyotes in the wild. Direct hybridizations between coyotes and gray wolves was never explicitly observed. Nevertheless, in a study that analyzed the molecular genetics of the coyotes as well as samples of historical red wolves and Mexican wolves from Texas, a few coyote genetic markers have been found in the historical samples of some isolated individual Mexican wolves. Likewise, gray wolf Y-chromosomes have also been found in a few individual male Texan coyotes. This study suggested that although the Mexican gray wolf is generally less prone to hybridizations with coyotes compared to the red wolf, there may have been exceptional genetic exchanges with the Texan coyotes among a few individual gray wolves from historical remnants before the population was completely extirpated in Texas. However, the same study also countered that theory with an alternative possibility that it may have been the red wolves, who in turn also once overlapped with both species in the central Texas region, who were involved in circuiting the gene-flows between the coyotes and gray wolves much like how the eastern wolf is suspected to have bridged gene-flows between gray wolves and coyotes in the Great Lakes region since direct hybridizations between coyotes and gray wolves is considered rare.

In tests performed on a sample from a taxidermied carcass of what was initially labelled as a chupacabra, mitochondrial DNA analysis conducted by Texas State University professor Michael Forstner showed that it was a coyote. However, subsequent analysis by a veterinary genetics laboratory team at the University of California, Davis concluded that, based on the sex chromosomes, the male animal was a coyote–wolf hybrid sired by a male Mexican wolf. It has been suggested that the hybrid animal was afflicted with sarcoptic mange, which would explain its hairless and blueish appearance.

A study in 2018 that analyzed wolf populations suspected to have had past interactions with domestic dogs found no evidence of significant dog admixture into the Mexican wolf. Another study in the same year was published in the PLOS Genetics Journal which analyzed the population genomics of gray wolves and coyotes from all over North America. This study detected the presences of coyote admixtures in various western gray wolf populations, all previously thought to be free of coyote-introgression, and found that the Mexican wolves carry 10% coyote admixture. The study's author also suggests that the admixture from coyotes may have also played a role in the basal phylogenetic placement of this subspecies.

Distribution

Early accounts of the distribution of the Mexican wolf included southeastern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and western Texas in the U.S., and the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico. This past distribution is supported by ecological, morphological, and physiographic data. The areas described coincide with the distribution of the Madrean pine-oak woodlands, a habitat which supports Coues’ white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus couesi) that were historically the Mexican wolf's main prey.

Today, following their reintroduction and conservation, Mexican wolves are widely distributed across over 40,000 km (9.88 million acres) of western New Mexico and eastern Arizona, largely coinciding with the Apache-Sitgreaves and Gila National Forests and the surrounding areas. Under the current Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, this area is categorized as predominantly Wolf Management Zone 1 (the former Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area). This plan designates the wolf experimental population area as all of New Mexico and Arizona, south of Interstate Highway 40. Wolves sometimes disperse outside of this area, though they are sometimes caught and returned to the management zones. In 2024, a breeding pair of wolves were released into Arizona's Peloncillo Mountains, which are in Wolf Management Zone 2. A small population of wolves have also been reintroduced to Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico.

History

Indigenous culture

The Mexican wolf was held in high regard in Pre-Columbian Mexico, where it was considered a symbol of war and the Sun. In the city of Teotihuacan, it was common practice to crossbreed Mexican wolves with dogs to produce temperamental, but loyal, animal guardians. Wolves were also sacrificed in religious rituals, which involved quartering the animals and keeping their heads as attire for priests and warriors. The remaining body parts were deposited in underground funerary chambers with a westerly orientation, which symbolized rebirth, the Sun, the underworld and the canid god Xolotl. The earliest written record of the Mexican wolf comes from Francisco Javier Clavijero's Historia de México in 1780, where it is referred to as Cuetzlachcojotl, and is described as being of the same species as the coyote, but with a more wolf-like pelt and a thicker neck.

The Apache call Mexican wolves "ba'cho" or "ma'cho." There is a "wolf song" that is passed down through oral tradition in the tribe, which was historically used to summon the wolf's power before battle. Other prayers and rituals have traditionally invoked the power of the wolf and other beings before deer hunts. Other indigenous names for the Mexican wolf include "shee’e" (Akimel O'odham/Pima) and "Ma’iitsoh" (Diné/Navajo). The Hopi call the wolf kachina (spirit being) "Kweo." The Havasupai have many traditional stories about Mexican wolves.

Decline

There was a rapid reduction of Mexican wolf populations in the Southwestern United States from 1915 to 1920; by the mid-1920s, livestock losses to Mexican wolves became rare in areas where the costs once ranged in the millions of dollars. Vernon Bailey, writing in the early 1930s, noted that the highest Mexican wolf densities occurred in the open grazing areas of the Gila National Forest, and that wolves were completely absent in the lower Sonora. He estimated that there were 103 Mexican wolves in New Mexico in 1917, though the number had been reduced to 45 a year later. By 1927, it had apparently become extinct in New Mexico. Sporadic encounters with wolves entering Texas, New Mexico and Arizona via Mexico continued through to the 1950s, until they too were driven away through traps, poison and guns. The last wild wolves to be killed in Texas were a male shot on December 5, 1970, on Cathedral Mountain Ranch and another caught in a trap on the Joe Neal Brown Ranch on December 28. Wolves were still being reported in small numbers in Arizona in the early 1970s, while accounts of the last wolf to be killed in New Mexico are difficult to evaluate, as all the purported "last wolves" could not be confirmed as genuine wolves rather than other canid species.

The Mexican wolf persisted longer in Mexico, as human settlement, ranching and predator removal came later than in the Southwestern United States. Wolf numbers began to rapidly decline during the 1930s–1940s, when Mexican ranchers began adopting the same wolf-control methods as their American counterparts, relying heavily on the indiscriminate usage of 1080.

Conservation and recovery

The Mexican wolf was listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 1976, with the Mexican Wolf Recovery Team being formed three years later by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The Recovery Team composed the Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, which called for the reestablishment of at least 100 wolves in their historic range through a captive breeding program. Between 1977 and 1980, four males and a pregnant female were captured in Durango and Chihuahua in Mexico to act as founders of a new "certified lineage". Three lineages were brought into the United States: McBride, Ghost Ranch and Aragón. Due to the limited number of founders for each lineage, these wolves can potentially carry the risks of inbreeding. However, cross-lineaged wolves have less inbreeding coefficients and greater reproductive success than purebred lineages. By 1999, with the addition of new lineages, the captive Mexican wolf population throughout the US and Mexico reached 178 individuals. Beginning in 1998, these captive-bred animals were subsequently released into the Apache National Forest in eastern Arizona, and allowed to recolonize east-central Arizona and south-central New Mexico, areas which were collectively termed the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area (BRWRA). The lack of livestock-free zones and tolerance for these captive wolves outside of their restoration area can be challenging for Mexican wolf conservation. The Recovery Plan called for the release of additional wolves in the White Sands Wolf Recovery Area in south-central New Mexico, should the goal of 100 wild wolves in the Blue Range area not be achieved.

On October 11, 2011, 5 wolves (2 males and 3 females) were released into Sonora's Madrean Sky Islands in Mexico. Since then, Mexico's National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP) has facilitated 19 wolf releases into the country.

Since 1998, 92 wolf deaths were recorded, with four occurring in 2012; these four were all due to illegal shootings. Releases have also been conducted in Mexico, and the first birth of a wild wolf litter in Mexico was reported in 2014. In 2015, a court ordered the U.S. Fish and Wildlife revise the management rules. According to a survey done on the population of the Mexican wolf in Alpine, Arizona, the recovery of the species is being negatively impacted due to poaching; poaching accounted for 50% of all Mexican wolf mortalities from 2008 to 2019. In an effort to fight the slowing recovery, GPS monitoring devices are being used to monitor the wolves. In 2016, 14 Mexican wolves were killed, making it the highest death count of any year since they were reintroduced into the wild in 1998. Two of the deaths were caused by officials trying to collar the animals. The rest of the deaths remain under investigation.

In July 2017, approximately 31 wild Mexican gray wolves inhabited Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico, in the northern Sierra Madre Occidental. In February 2018, five more wolves were released in Chihuahua, bringing the total wild population in Mexico (Sonora and Chihuahua) to thirty-seven wolves. In 2018, six Mexican wolf pups from the Endangered Wolf Center were sent to dens in Arizona and New Mexico for their survival. The 2019 census found more than 30 wolves in Mexico.

Eight Mexican wolf cubs were born at the Desert Museum in Saltillo, Coahuila on July 1, 2020. In March 2021, a family of nine Mexican gray wolves (a breeding pair of wolves and their seven pups) were released into the wild of northern Mexico, bringing the total number of wolves in Mexico to around 40 wild individuals.

Captive-born wolves may be released as a well-bonded pack consisting of a breeding pair along with their pups. Captive-born pups, who are less than 14 days old, are also released by being placed with similarly aged pups to be raised as wild wolves. In 2021, 22 pups were placed into wild dens to be raised by surrogate packs under this method known as cross-fostering. This mitigates some of the potential inbreeding depression issues by introducing more distantly related wolves from captivity.

In June 2021, a year-old male Mexican gray wolf named Anubis traveled out of the Mexican Wolf Recovery Area and settled in the Coconino National Forest in central Arizona. He was one of several Mexican gray wolves to have dispersed into the area over several years; the male individual may be the first permanent resident of Mexican gray wolves to settle in the Coconino National Forest. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was ordered by the court to review the rule that caps the U.S. population at 325 wolves. In 2021, a male Mexican gray wolf was stopped from crossing from New Mexico into Mexico by a section of border wall. 2022 had the lowest number of mortalities (12 total) since 2017.

| Year | Total Population | Total Surviving Pups | Arizona Population | New Mexico Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1999 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 6 |

| 2000 | 22 | 5 | 15 | 7 |

| 2001 | 26 | 3 | 21 | 4 |

| 2002 | 41 | 20 | 34 | 7 |

| 2003 | 55 | 21 | 42 | 13 |

| 2004 | 44-48 | 17-19 | 26 | 18 |

| 2005 | 35-49 | 10-17 | 24 | 18 |

| 2006 | 59 | 21 | 25 | 34 |

| 2007 | 52 | 9 | 29 | 23 |

| 2008 | 52 | 11 | 29 | 23 |

| 2009 | 42 | 7 | 27 | 15 |

| 2010 | 50 | 14 | 29 | 21 |

| 2011 | 67 | 27 | 32 | 35 |

| 2012 | 80 | 23 | 37 | 43 |

| 2013 | 88 | 19 | 40 | 48 |

| 2014 | 112 | 40 | 58 | 54 |

| 2015 | 98 | 23 | 50 | 48 |

| 2016 | 114 | 50 | 64 | 50 |

| 2017 | 117 | 29 | 63 | 54 |

| 2018 | 131 | 47 | 64 | 67 |

| 2019 | 163 | 52 | 76 | 87 |

| 2020 | 186 | 64 | 72 | 114 |

| 2021 | 196 | 56 | 84 | 112 |

| 2022 | 241 | 81 | 105 | 136 |

| 2023 | 257 | 86 | 113 | 144 |

Current population

On March 9, 2022, two new breeding pairs of Mexican gray wolves were released into the wild in the state of Chihuahua in northern Mexico, bringing the total number of wild Mexican gray wolves in the country to around 35-45 individuals.

In March 2024, the wild Mexican wolf population of the United States totaled at least 257 individuals: 144 in New Mexico (36 packs and 15 breeding pairs) and 113 in Arizona (20 packs and 11 breeding pairs). At least 86 out of the known 138 pups born in 2023 survived until the year's end (62% survival rate). 44% of the U.S. Mexican wolf population is collared with GPS and radio collars. 2023 represented the 8th consecutive year of population growth, and a 6% increase compared to 2022. At least 31 wolves died in 2023. 2024 marked the 100th wolf pup to be cross-fostered.

The total captive Mexican wolf population is 380 individuals, across over 60 facilities.

Interagency Field Team

The wild Mexican wolf population in the United States is managed by the Interagency Field Team (IFT), whose collaborating participants include the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the US Forest Service, the White Mountain Apache Tribe, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, USDA APHIS Wildlife Services, National Park Service, Species Survival Plan, and Bureau of Land Management.

The IFT has a partnership with Mexico's National Commission for Natural Protected Areas and Directorate General for Wildlife to continue binational collaboration for Mexican wolf recovery.

The IFT employs active conservation. Anti-poaching is strongly enforced, as poaching has been found to increase during periods of relaxed protection. Wolf locations, movements, and populations are monitored via tracking collared individuals and the use of remote cameras. The team uses several methods to mitigate predation on livestock. Some pastures are surrounded by fladry (flagging) hung on electrified fences. Range riders accompany cattle to discourage wolf presence. When wolves are spotted near livestock, the range riders employ non-lethal ammunition such as cracker shells and rubber bullets. Wolf packs that live near livestock areas are sometimes given diversionary food caches. Livestock producers are given financial compensation when their animals are killed by wolves, and are paid to remove cattle carcasses in order to discourage wolf scavenging. Individual wolves that are particularly harmful to livestock can be selectively removed, though these management removals have largely decreased over time.

Revised Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan

In September 2022, the US Fish and Wildlife Service published the court-ordered Second Revision of the Recovery Plan. The plan provides a detailed assessment of the population, ecology, threats, management strategies, and future initiatives. It lists several criteria for downlisting (changing the classification from Endangered to Threatened) and delisting (removal of the species from the Federal Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants).

The criteria for delisting in the United States include: a stable or growing population over 8 years, with an average of at least 320 individuals; the implementation of State and Tribal regulations to ensure that the population remains this size or greater; and all available genetic diversity from the captive population is incorporated into the wild via reintroduction. Similar criteria are in place for Mexico, except for a lower minimum population requirement of 200 individuals.

Ecology and behavior

Life history

Mexican wolves live in packs of approximately 4 to 8 individuals, which hunt collaboratively. Like other wolves, Mexican wolves communicate with scent marking, body postures, and a range of calls that include barks, growls, whines, and howling. Packs are typically composed of a monogamous breeding pair and their offspring of several years. A pack's home range varies based on several factors, including the time of year, pack and litter size, ungulate biomass, tree cover, winter snow depth, and human population density. Home ranges average 446 km; shifting from an average 234 km during denning season, to 373 km post-denning, to 518 km during non-denning season. Mexican wolves most frequently inhabit areas away from developed land and open areas, closer to water bodies and dirt roads, and in forested areas with about 16-30% canopy cover. They are typically most active at dawn and the middle of the night, but also can be active at dusk depending on the season. Previous literature has shown gray wolves are most active at dawn and dusk, however, much of this research comes from national parks and protected areas, so it is theorized Mexican wolves have shifted some of their activity to night to avoid people. Mexican wolves breed in February, and gestate for 63 days. They give birth to litters averaging 4-6 pups in April and early May. When wolves reach the age of 1–2 years old, they disperse in search of a mate to begin their own pack. Mexican wolves in the wild typically live 6–8 years.

Diseases

Mexican wolves have been subject to diseases such as canine parvovirus and canine distemper virus in the wild, and eastern equine encephalitis virus in captivity.

Diet

Mexican wolves, like other wolves worldwide, are opportunistic predators and primarily prey on large ungulates. In the United States population, Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus canadensis nelsoni) make up about 76–80% of their prey. The most common demographic of elk that are predated on are calves, which make up two thirds of all native ungulates that the wolves prey on. Elk appear to attempt to balance their nutritional demands with predation risk from Mexican wolves seasonally and incorporate both proactive and reactive responses to mitigate predation risk from Mexican wolves (and mountain lions). They also spend a greater proportion of time foraging and vigilant, and a lower proportion of time resting, in areas with greater wolf predation risk. Other native prey include mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), Coues white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus couesi), collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu), wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), and small mammals such as rabbits and squirrels. Up to 16% of their diet may include domestic cattle (Bos taurus) in certain parts of their range, especially in locations where the cattle graze and calve year-round as opposed to seasonally. Investigations have suggested that reports of wolf depredation on livestock were sometimes exaggerated or fabricated. As a result, the Recovery Program has adopted more stringent standards of proof to determine which animals were killed by wolves.

The diet of wolves in Mexico differs from that of the United States population due to the absence of elk and most other wild ungulates in the wolves' Mexican range. In Mexico, white-tailed deer make up approximately 36% of their diet, while domestic cattle comprise about 25% and diversionary food caches from wildlife managers provide an additional 22%. The rest of their diet predominantly consists of smaller prey including wild turkeys, rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), skunks (Mephitis spp.), squirrels (Otospermophilus variegatus), and other small mammals and birds, with very occasional collared peccaries and domestic horses (Equus caballus).

Competition

Mexican wolves share their habitat and prey with other carnivores, including mountain lions (Puma concolor), American black bears (Ursus americanus), coyotes (Canis latrans), bobcats (Lynx rufus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). Historically, they also once competed with the locally extinct jaguar (Panthera onca) and the currently extinct Mexican grizzly bear (Ursus arctos). Unlike wolves elsewhere, Mexican wolves do not significantly affect the behavior or populations of competing carnivore species.

Habitat

See also: Apache–Sitgreaves National Forests and Gila National ForestThe Mexican wolf's range is predominantly located in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest and the Gila National Forest, a mountainous ecosystem with many lakes, streams, and other varied terrain. In this region, the most common habitat types are Ponderosa pine forest, pinyon-juniper woodland, and Madrean encinal and pine-oak woodland. Other habitat includes mixed-conifer forest, semi-desert grassland, Great Basin and Colorado Plateau grassland-steppe, subalpine grassland, aspen forest, and spruce-fir forest. Aspen research suggests that Mexican wolves have not yet altered elk behavior and populations so as to trigger a trophic cascade in the manner observed in Yellowstone National Park (e.g. facilitating aspen regeneration), likely due to the fact that the Mexican wolves still have a relatively small, highly dispersed population.

This habitat contains at least 537 plant and animal species. Additional mammals include Abert's squirrels, white-nosed coatis, ringtails, bighorn sheep, and pronghorn. Birds vary from raptors like Mexican spotted owls, Apache northern goshawks, and bald eagles; to waterfowl such as American white pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos), tundra swans (Cygnus columbianus), and pied-bill grebes (Podilymbus podiceps); to songbirds like the pygmy nuthatch (Sitta pygmaea). Streams are inhabited by native fishes including Apache trout (Oncorhynchus apache), Bluehead and desert sucker (Catostomus discobolus and C. clarkii), Loach Minnow (Rhinichthys cobitis), Roundtail Chub (Gila robusta), and many more. Local reptiles and amphibians include bullsnakes, black-tailed rattlesnakes, crevice spiny lizards, and New Mexico spadefoot toads.

In popular culture

A Mexican wolf pack features in Ernest Thompson Seton's 1898 short story "Lobo, the King of Currumpaw." The story, largely based on Seton's real-life experience, features Lobo and his mate, Blanca, the alpha pair of their pack, who predate upon the vast herds of livestock on the Currumpaw ranch in New Mexico. Seton tells about the conflict between the wolves and the many hunters and trappers who they outwit, until Seton himself manages to kill the breeding pair. In a rarity for the time, Seton portrayed the wolves in a sympathetic light, and himself, the hunter, as the antagonist. Seton became an advocate for wolf conservation later in his life as a result of his experience. Lobo's pelt is on display at Philmont Scout Ranch in Cimarron, New Mexico.

Decades later, conservationist Aldo Leopold had a similar life changing encounter when he killed a Mexican wolf in the Gila Wilderness in 1909. In his famous essay, Thinking Like a Mountain, Leopold highlighted the “green fire” in the dying wolf's eyes to provide empathy to the animal, while also explaining the ecological benefits that wolves provide to their habitat. Like Seton, Leopold would go on to become an advocate for predator conservation.

In 2023 the Mexican wolf was featured on a United States Postal Service Forever stamp as part of the Endangered Species set, based on a photograph from Joel Sartore's Photo Ark. The stamp was dedicated at a ceremony at the National Grasslands Visitor Center in Wall, South Dakota.

See also

Notes

- Spanish: Lobo mexicano; Nahuatl languages: Cuetlāchcoyōtl

References

- "Canis lupus baileyi". explorer.natureserve.org.

- "Revision to the Nonessential Experimental Population of the Mexican Wolf; Final Rule" (PDF). Federal Register. 87 (126): 39348–39373. July 1, 2022.

- ^ Chambers SM, Fain SR, Fazio B, Amaral M (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

Note:"The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service."

- ^ Valadez, Raúl; Rodríguez, Bernardo; Manzanilla, Linda; Tejeda, Samuel (2016). "Dog-wolf Hybrid Biotype Reconstruction from the Archaeological City of Teotihuacan in Prehispanic Central Mexico" (PDF). In Snyder, Lynn M; Moore, Elizabeth A. (eds.). Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction. Oxbow Books. pp. 120–130. ISBN 978-1-78570-428-4.

- ^ Nie, M. A. (2003), Beyond Wolves: The Politics of Wolf Recovery and Management, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 118–119, ISBN 0816639787

- ^ "Wild Population of Mexican Wolves Grows for Fifth Consecutive Year". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. March 12, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ "Mexican Wolf Numbers Soar Past 200 in Latest Count". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. February 27, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Mexican Wolf Population Grows for Eighth Consecutive Year". www.fws.gov. March 5, 2024. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 350, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ^ "Conserving the Mexican Wolf". www.fws.gov. December 11, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Bailey, V. (1932), Mammals of New Mexico. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Biological Survey. North American Fauna No. 53. Washington, D.C. Pages 303–308.

- Nelson, E. W.; Goldman, E. A. (May 1929). "A New Wolf from Mexico". Journal of Mammalogy. 10 (2): 165. doi:10.2307/1373839. JSTOR 1373839.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering (2019). Evaluating the Taxonomic Status of the Mexican Gray Wolf and the Red Wolf. doi:10.17226/25351. ISBN 978-0-309-48824-2. PMID 31211533. S2CID 134662152.

- ^ Tomiya, Susumu; Meachen, Julie A. (January 2018). "Postcranial diversity and recent ecomorphic impoverishment of North American gray wolves". Biology Letters. 14 (1): 20170613. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0613. PMC 5803591. PMID 29343558.

- Koblmüller, Stephan; Vilà, Carles; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Dabad, Marc; Ramirez, Oscar; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; Leonard, Jennifer A. (September 2016). "Whole mitochondrial genomes illuminate ancient intercontinental dispersals of grey wolves (Canis lupus)". Journal of Biogeography. 43 (9): 1728–1738. Bibcode:2016JBiog..43.1728K. doi:10.1111/jbi.12765. S2CID 88740690.

- ^ Leonard, Jennifer A.; Vilà, Carles; Fox-Dobbs, Kena; Koch, Paul L.; Wayne, Robert K.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (July 2007). "Megafaunal Extinctions and the Disappearance of a Specialized Wolf Ecomorph". Current Biology. 17 (13): 1146–1150. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.1146L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072. hdl:10261/61282. PMID 17583509. S2CID 14039133.

- Cox, C. B.; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard (2016). Biogeography: An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-118-96858-1.

- Editorial Board (April 2012). Concise Dictionary of Science. V&s Publishers. ISBN 978-93-81588-64-2.

- Arora, Devender; Singh, Ajeet; Sharma, Vikrant; Bhaduria, Harvendra Singh; Patel, Ram Bahadur (June 30, 2015). "HgsDb: Haplogroups Database to understand migration and molecular risk assessment". Bioinformation. 11 (6): 272–275. doi:10.6026/97320630011272. PMC 4512000. PMID 26229286.

- pp. 106–107 in Miklósi, Ádám (2014). "Comparative overview of Canis". Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. pp. 97–123. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199646661.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-964666-1.

- ^ Leonard, Jennifer A.; Vilà, Carles; Wayne, Robert K. (January 2005). "FAST TRACK: Legacy lost: genetic variability and population size of extirpated US grey wolves (Canis lupus)". Molecular Ecology. 14 (1): 9–17. Bibcode:2005MolEc..14....9L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02389.x. PMID 15643947. S2CID 11343074.

- Ersmark, Erik; Klütsch, Cornelya F. C.; Chan, Yvonne L.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Fain, Steven R.; Illarionova, Natalia A.; Oskarsson, Mattias; Uhlén, Mathias; Zhang, Ya-ping; Dalén, Love; Savolainen, Peter (December 2, 2016). "From the Past to the Present: Wolf Phylogeography and Demographic History Based on the Mitochondrial Control Region". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00134.

- Wilson, Paul J.; Rutledge, Linda Y. (July 2021). "Considering Pleistocene North American wolves and coyotes in the eastern Canis origin story". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (13): 9137–9147. Bibcode:2021EcoEv..11.9137W. doi:10.1002/ece3.7757. PMC 8258226. PMID 34257949.

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2022. Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, Second Revision. Region 2, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

- ^ Hailer, Frank; Leonard, Jennifer A. (October 8, 2008). "Hybridization among Three Native North American Canis Species in a Region of Natural Sympatry". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3333. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3333H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003333. PMC 2556088. PMID 18841199.

- ^ "Texas State University Researcher Helps Unravel Mystery of Texas 'Blue Dog' Claimed to be Chupacabra" Archived March 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. bionews-tx.com (2013-09-01)

- Long, Sonny (October 31, 2008) "DNA results show chupacabra animal is mixture of coyote, Mexican wolf". Victoria Advocate.

- Fitak, Robert R; Rinkevich, Sarah E; Culver, Melanie (May 11, 2018). "Genome-Wide Analysis of SNPs Is Consistent with No Domestic Dog Ancestry in the Endangered Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi)". Journal of Heredity. 109 (4): 372–383. doi:10.1093/jhered/esy009. PMC 6281331. PMID 29757430.

- Sinding, MS; Gopalakrishan, S; Vieira, FG; Samaniego Castruita, JA; Raundrup, K; Heide Jørgensen, MP; Meldgaard, M; Petersen, B; Sicheritz-Ponten, T; Mikkelsen, JB; Marquard-Petersen, U; Dietz, R; Sonne, C; Dalén, L; Bachmann, L; Wiig, Ø; Hansen, AJ; Gilbert, MTP (2018). "Population genomics of grey wolves and wolf-like canids in North America". PLOS Genet. 14 (11): e1007745. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007745. PMC 6231604. PMID 30419012.

- Heffelfinger, James R.; Nowak, Ronald M.; Paetkau, David (July 2017). "Clarifying historical range to aid recovery of the Mexican wolf". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 81 (5): 766–777. Bibcode:2017JWMan..81..766H. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21252.

- ^ Vander Lee, B., Smith, R., & Bate, J. (2004). Ecological & Biological Diversity of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests In Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3. The Nature Conservancy.

- ^ Smith, J. B.; Greenleaf, A. R.; Oakleaf, J. K. (2023). "Kill rates on native ungulates by Mexican gray wolves in Arizona and New Mexico". Journal of Wildlife Management. 87 (8): e22491. Bibcode:2023JWMan..87E2491S. doi:10.1002/jwmg.22491. S2CID 261597753.

- 88 FR 10258

- ^ "Mexican wolf experimental pop area map". www.fws.gov. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- "Female Mexican Wolf Captured and Paired with Mate in Captivity". www.fws.gov. December 11, 2023.

- Evans, Hayleigh. "Two Mexican gray wolves are released in southern Arizona's Sky Islands. Why that matters". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Jenkinson, Orlando (March 11, 2022). "Endangered Mexican Wolves Released Into Chihuahua Wilderness". Newsweek.

- Clavijero, Francisco Javier (1817) The history of Mexico, Volume 1, Thomas Dobson, p. 57

- "Ba'cho". Arizona Highways. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Rinkevich, Sarah E (2012). An assessment of abundance, diet, and cultural significance of Mexican gray wolves in Arizona (Thesis). ProQuest 1020132667.

- ^ 1982. Mexican wolf recovery plan, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- "AZGFD: Record number of Mexican wolf pups fostered into the wild". KTAR.com. June 8, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Hedrick, P. W.; Fredrickson, R. J. (January 2008). "Captive breeding and the reintroduction of Mexican and red wolves". Molecular Ecology. 17 (1): 344–350. Bibcode:2008MolEc..17..344H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03400.x. PMID 18173506. S2CID 44303787.

- Povilitis, Anthony; Parsons, David R.; Robinson, Michael J.; Dusti Becker, C. (August 2006). "The Bureaucratically Imperiled Mexican Wolf". Conservation Biology. 20 (4): 942–945. Bibcode:2006ConBi..20..942P. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00489.x. JSTOR 3879161. PMID 16922210. S2CID 43139520.

- "Mexican Grey Wolves released in Sonora". Wild Sonora.

- 2012. Mexican Wolf Recovery Program: Progress Report #15, US Fish and Wildlife Service

- Gannon, Megan (July 21, 2014). "First Litter of Wild Wolf Pups Born in Mexico". Live Science.

- Skabelund, Adrian (July 7, 2021). "Conservation groups oppose removal as wildlife managers monitor Mexican gray wolf near Flagstaff". Arizona Daily Sun. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Breck, Stewart W.; Davis, Amy J.; Oakleaf, John K.; Bergman, David L.; deVos, Jim; Greer, J. Paul; Pepin, Kim (August 4, 2023). "Factors affecting the recovery of Mexican wolves in the Southwest United States". Journal of Applied Ecology. 60 (10): 2199–2209. Bibcode:2023JApEc..60.2199B. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.14483. ISSN 0021-8901.

- "How Mexican gray wolves are tracked in the wild". USA Today (2016-01-28).

- "Confirmed: 14 Endangered Mexican Gray Wolves Killed in 2016". Gohunt. January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- "Feds: 14 endangered Mexican wolves found dead in 2016". AZCentral. January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019). "Is the Mexican Gray Wolf a Valid Subspecies?". Evaluating the Taxonomic Status of the Mexican Gray Wolf and the Red Wolf. pp. 41–50. doi:10.17226/25351. ISBN 978-0-309-48824-2. PMID 31211533. S2CID 134662152.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Liberan 5 ejemplares de lobo mexicano en Chihuahua". El Universal (in Spanish). February 9, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- Clark, Patrick (April 26, 2018). "Endangered Mexican Wolf pups transferred to New Mexico and Arizona". FOX 2. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- Pirehpour, Kevin /Cronkite (February 9, 2021). "Habitat plays crucial role in protecting two wolf groups in U.S., Mexico". Cronkite News – Arizona PBS. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- "Las tiernas imágenes de los ocho cachorros de lobo gris mexicano que nacieron en Saltillo". Infobae (in European Spanish). July 2, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- Montoya Bryan, Susan (March 12, 2021). "Wild population of endangered Mexican wolves keeps growing". Yahoo News. Associated Press. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- "Record number of endangered Mexican gray wolf pups placed into dens to be raised by surrogate packs in Southwest U.S." KTLA. June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- Clement, Matthew J.; Oakleaf, John K.; Heffelfinger, James R.; Gardner, Colby; deVos, Jim; Rubin, Esther S.; Greenleaf, Allison R.; Dilgard, Bailey; Gipson, Philip S. (July 22, 2024). "An evaluation of potential inbreeding depression in wild Mexican wolves". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 88 (7). Bibcode:2024JWMan..88E2640C. doi:10.1002/jwmg.22640. hdl:2346/99462. ISSN 0022-541X.

- Shumaker, Scott (August 26, 2021). "Lone Mexican wolf leaves mark in summer out west". Sedona Red Rock News. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- Shumaker, Scott (June 25, 2021). "Wolf Anubis roams now-closed national forests". Sedona Red Rock News. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- Botts, Lindsey (September 18, 2021). "Wildlife officials drew a line at I-40 for Mexican gray wolves, but has it hurt recovery?". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- "An endangered wolf went in search of a mate. The border wall blocked him". National Geographic Society. January 21, 2022. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022.

- "Wild population of Mexican wolves grows in size for sixth year". FWS.gov. March 30, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Humphrey, Jeff and Lambert, Lynda (February 13, 2015) 2014 Mexican Wolf Population Survey Complete – Population Exceeds 100 Archived September 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Calma, Justine (March 18, 2020). "Mexican gray wolf numbers in the US soared in 2019". The Verge. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Mexican Wolf Population Rises to at Least 163 Animals | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. February 19, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- "2018 Mexican Wolf Count Cause for Optimism | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. February 19, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- "2013 Mexican wolf population survey is complete | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. February 19, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- Protegidas, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales. "La Conanp cierra el 2020 con la decimocuarta y decimoquinta liberación de lobo mexicano en la Reserva de la Biósfera Janos, en Chihuahua". gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- "Mexico releases two pairs of endangered gray wolves – Albuquerque Journal". www.abqjournal.com. March 9, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- "Survey Finds 257 Mexican Gray Wolves Living in U.S. Southwest". Center for Biological Diversity. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- "Arizona Game and Fish celebrates 100th Mexican wolf pup fostered into the wild". azfamily.com. May 8, 2024.

- "Partners Sign Letter of Intent to Forward Collaborative Binational Approach to Mexican Wolf Recovery". FWS.gov. July 13, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- Louchouarn, Naomi X.; Santiago-Ávila, Francisco J.; Parsons, David R.; Treves, Adrian (March 2021). "Evaluating how lethal management affects poaching of Mexican wolves". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (3). Bibcode:2021RSOS....800330L. doi:10.1098/rsos.200330. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 8074884. PMID 33959305.

- Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife (January 30, 2021). "Recovering Mexican Wolves: How Radio Collars Contribute to Conservation". Medium. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- Russo, Brianna M.; Jones, Andrew S.; Clement, Matthew J.; Fyffe, Nathan; Mesler, Jacob I.; Rubin, Esther S. (June 2023). "Camera trapping as a method for estimating abundance of Mexican wolves". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 47 (2). doi:10.1002/wsb.1416. ISSN 2328-5540.

- Wyland, Scott (December 26, 2023). "N.M. ranchers to get $3 million to protect against predators like Mexican wolves". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- "Of Men and Wolves: & Tolerance on the Range". Lobos of the Southwest. July 24, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- "Mexican Gray Wolf". defenders.org. December 12, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- "Carcass removal program aims to reduce Mexican wolf depredation losses". Williams News. February 14, 2023. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- Servín, Jorge (2000). "Duration and frequency of chorus howling of the mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi)". Acta Zoológica Mexicana (80): 223–231. doi:10.21829/azm.2000.80801902. ISSN 0065-1737.

- "Vertebrate Zoology Project: Variation in Howling Between Captive and Wild Wolves (Canis lupus) and the Possible Implications for the Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi)". www.unm.edu. 1996. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Conserving the Mexican Wolf". FWS.gov. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- Lichwa, Evelyn (January 1, 2021). "Ecological and social drivers of Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) home range patterns across spatiotemporal scales". Cal Poly Humboldt Theses and Projects.

- ^ Thompson, Cara J. (2022). "Elk Habitat Selection in Response to Predation Risk from Mexican Gray Wolves". New Mexico State University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. ProQuest 2724219425.

- Guajardo, C. A. (2023). An analysis of canopy cover within the home ranges of Mexican wolves (Canis lupus baileyi) reintroduced into New Mexico and Arizona (Unpublished thesis). Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas.

- "Mexican Gray Wolf". Wildlife Science Center. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- Justice-Allen, Anne; Clement, Matthew J. (2019). "Effect of Canine Parvovirus and Canine Distemper Virus on the Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) Population in the USA". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 55 (3): 682–688. doi:10.7589/2018-07-175. PMID 30802181. S2CID 73480319.

- Thompson, Kimberly A.; Henderson, Eileen; Fitzgerald, Scott D.; Walker, Edward D.; Kiupel, Matti (April 2021). "Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus in Mexican Wolf Pups at Zoo, Michigan, USA". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 27 (4): 1173–1176. doi:10.3201/eid2704.202400. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 8007284. PMID 33754982.

- Hedrick, Philip W.; Lee, Rhonda N.; Buchanan, Colleen (2003). "Canine Parvovirus Enteritis, Canine Distemper, and Major Histocompatibility Complex Genetic Variation in Mexican Wolves". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 39 (4): 909–913. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-39.4.909. PMID 14733289.

- ^ Reed, Janet E.; Ballard, Warren B.; Gipson, Philip S.; Kelly, Brian T.; Krausman, Paul R.; Wallace, Mark C.; Wester, David B. (November 2006). "Diets of Free-Ranging Mexican Gray Wolves in Arizona and New Mexico". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 34 (4): 1127–1133. doi:10.2193/0091-7648(2006)34[1127:DOFMGW]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 55402865.

- ^ Merkle, Jerod A.; Krausman, Paul R.; Stark, Dan W.; Oakleaf, John K.; Ballard, Warren B. (December 2009). "Summer Diet of the Mexican Gray Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi)". The Southwestern Naturalist. 54 (4): 480–485. doi:10.1894/CLG-26.1. JSTOR 40588583. S2CID 51689073.

- Farley, Zachary J. (2022). "Influence of Mexican Gray Wolves on Elk Behavior in Relation to Maternal Constraints, Multitasking, and Predation Risk". New Mexico State University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. ProQuest 2676582923.

- ^ Carrera, Rogelio; Ballard, Warren; Gipson, Philip; Kelly, Brian T.; Krausman, Paul R.; Wallace, Mark C.; Villalobos, Carlos; Wester, David B. (February 2008). "Comparison of Mexican Wolf and Coyote Diets in Arizona and New Mexico". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 72 (2): 376–381. doi:10.2193/2007-012. S2CID 84104944.

- Breck, Stewart W.; Kluever, Bryan M.; Panasci, Michael; Oakleaf, John; Johnson, Terry; Ballard, Warren; Howery, Larry; Bergman, David L. (February 1, 2011). "Domestic calf mortality and producer detection rates in the Mexican wolf recovery area: Implications for livestock management and carnivore compensation schemes". Biological Conservation. 144 (2): 930–936. Bibcode:2011BCons.144..930B. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.12.014. ISSN 0006-3207. S2CID 4610159.

- Roberts, Spencer (May 24, 2022). "Endangered Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery Is Being "Sabotaged" by Ranchers Who Claim the Canines Are Killing Cattle — and the Federal Employees Who Sign Off on Reports". The Intercept. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- TucsonSentinel.com; Shailer, Daniel. "Not so big or bad?: Stricter probes into dead cattle to curtail 'endemic antagonism' vs. gray wolves". TucsonSentinel.com. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- "USDA APHIS Wildlife Services (WS) Evidence Standards for Determining Livestock Depredations by Mexican Wolves in Arizona and New Mexico" (PDF). Western Watersheds Project. August 2023.

- Reyes-Díaz, Jorge L.; Lara-Díaz, Nalleli E.; Camargo-Aguilera, María Gabriela; Saldívar-Burrola, Laura L.; López González, Carlos A. (2024). "The importance of livestock in the diet of Mexican wolf Canis lupus baileyi in northwestern Mexico". Wildlife Biology. 2024 (6): e01272. doi:10.1002/wlb3.01272. ISSN 1903-220X.

- "Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest – National Forest Foundation". www.nationalforests.org. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- Grant, Richard; Hatcher, Bill. "The Return of the Great American Jaguar". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- Hoskinson, Joshua Scott (2018). "Mexican Gray Wolves and the Ecology of Fear: A Comparative Assessment of Community Assemblages in Arizona". The University of Arizona. hdl:10150/628170.

- Beschta, Robert L.; Ripple, William J. (July 2010). "Mexican wolves, elk, and aspen in Arizona: Is there a trophic cascade?". Forest Ecology and Management. 260 (5): 915–922. Bibcode:2010ForEM.260..915B. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.06.012.

- "Birds of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest". White Mountains Online. February 15, 2023.

- Mimbres, Mailing Address: 26 Jim Bradford Trail; Us, NM 88049 Phone: 575-536-9461 Contact. "Reptiles/Amphibians – Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Lobo, the King of Currumpaw by Ernest Seton Thompson". CommonLit. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- Vea, Tanner (October 8, 2010). "The Wolf That Changed America ~ The Photographs and Artwork of Ernest Thompson Seton". Nature. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- "About Ernest Thompson Seton". Ernest Thompson Seton Legacy Project. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- "About the Ernest Thompson Seton Legacy Project and Curator David L. Witt". Ernest Thompson Seton Legacy Project. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- "Lobo, the King of Currumpaw". Philmont Scout Ranch. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. Oxford University Press, New York.

- "Leopold and a New Vision for Predators". Lobos of the Southwest. May 5, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- "Episode 20: A Mexican wolf pup's journey into the wild". Podcasts. May 23, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- Parsons, David R. (1998). ""Green Fire" Returns to the Southwest: Reintroduction of the Mexican Wolf". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 26 (4): 799–807. ISSN 0091-7648. JSTOR 3783553.

- "Postal Service Spotlights Endangered Species". United States Postal Service. April 19, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

Further reading

- Bass, Rick (2007), The New Wolves: The Return of the Mexican Wolf to the American Southwest, Globe Pequot. ISBN 9781599212289 (Originally published 1998)

- Holaday, B. (2003), Return of the Mexican Gray Wolf: Back to the Blue, University of Arizona Press, ISBN 0816522960

- McBride, Roy T. (1980). The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi): a historical review and observations on its status and distribution. hdl:2027/umn.31951d00274892o. OCLC 762059287.

- McCarthy, Cormac (1994), The Crossing, Everyman's Library Knopf, ISBN 0375407936, A poignant fictional account of a young cowboy's capture of a wolf.

- Robinson, M. (2005), Predatory Bureaucracy: The Extermination of Wolves and the Transformation of the West, University Press of Colorado, ISBN 0870818198

- Shaw, H. (2002), The Wolf in the Southwest: The Making of an Endangered Species, High-Lonesome Books, ISBN 0944383599

External links

- The Mexican Wolf Recovery Plan, FWS

- Mexican Gray Wolves in the Southwest USDA APHIS Wildlife Services

- Mexicanwolves.org

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Canis lupus baileyi | |

- NatureServe critically imperiled species

- ESA endangered species

- Subspecies of Canis lupus

- Carnivorans of North America

- Mammals of Mexico

- Mammals of the United States

- Wolves in the United States

- Fauna of Northern Mexico

- Fauna of Northeastern Mexico

- Fauna of the Southwestern United States

- Fauna of the Chihuahuan Desert

- Fauna of the Sonoran Desert

- Natural history of the Mexican Plateau

- Biota of New Mexico

- Natural history of Arizona

- Natural history of Sonora

- Mammals described in 1929

- Taxa named by Edward William Nelson

- Wolves

- Endangered biota of Mexico

- Endangered fauna of the United States

- Endangered fauna of North America

- Fauna of the Sierra Madre Occidental