| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "The Nun's Priest's Tale" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

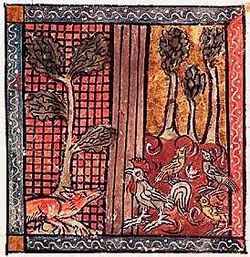

"The Nun's Priest's Tale" (Middle English: The Nonnes Preestes Tale of the Cok and Hen, Chauntecleer and Pertelote) is one of The Canterbury Tales by the Middle English poet Geoffrey Chaucer. Composed in the 1390s, it is a beast fable and mock epic based on an incident in the Reynard cycle. The story of Chanticleer and the Fox became further popularised in Britain through this means.

The tale and framing narrative

The narrative of 695-lines includes a prologue and an epilogue. The prologue links the story with the previous Monk's Tale, a series of short accounts of toppled despots, criminals and fallen heroes, which prompts an interruption from the knight. The host upholds the knight's complaint and orders the monk to change his story. The monk refuses, saying he has no lust to pleye, and so the Host calls on the Nun's Priest to give the next tale. There is no substantial depiction of this character in Chaucer's "General Prologue", but in the tale's epilogue the Host is moved to give a highly approving portrait which highlights his great physical strength and presence.

The fable concerns a world of talking animals who reflect both human perception and fallacy. Its protagonist is Chauntecleer, a proud cock (rooster) who dreams of his approaching doom in the form of a fox. Frightened, he awakens Pertelote, the chief favourite among his seven wives. She assures him that he only suffers from indigestion and chides him for paying heed to a simple dream. Chauntecleer recounts stories of prophets who foresaw their deaths, dreams that came true, and dreams that were more profound (for instance, Cicero's account of the Dream of Scipio). Chauntecleer is comforted and proceeds to greet a new day. Unfortunately for Chauntecleer, his own dream was also correct. A col-fox, ful of sly iniquitee (line 3215), who had previously tricked Chauntecleer's father and mother to their downfall, lies in wait for him in a bed of wortes.

When Chauntecleer spots this daun Russell (line 3334), the fox plays to his prey's inflated ego and overcomes the cock's instinct to escape by insisting he would love to hear Chauntecleer crow just as his amazing father did, standing on tiptoe with neck outstretched and eyes closed. When the cock does so, he is promptly snatched from the yard in the fox's jaws and slung over his back. As the fox flees through the forest, with the entire barnyard giving chase, the captured Chauntecleer suggests that he should pause to tell his pursuers to give up. The predator's own pride is now his undoing: as the fox opens his mouth to taunt his pursuers, Chauntecleer escapes from his jaws and flies into the nearest tree. The fox tries in vain to convince the wary rooster of his repentance; it now prefers the safety of the tree and refuses to fall for the same trick a second time.

The Nun's Priest is characterised by the way that he elaborates his slender tale with epic parallels drawn from ancient history and chivalry, giving a display of learning which, in the context of the story and its cast, can only be comic and ironic. But in contrast, the description of the poor widow and the chicken yard of her country cottage with which the tale opens is true to life and has been quoted as authentic in discussions of the living conditions of the mediaeval peasant. By way of conclusion, the Nun's Priest goes on to reconcile the sophistication of his courtly performance with the simplicity of the tale within the framing narrative by admonishing the audience to be careful of reckless decisions and of truste on flaterye.

Adaptations

Robert Henryson used Chaucer's tale as a source for his Taill of Schir Chanticleir and the Foxe, the third poem in his Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian, composed in or around the 1480s. Later, the poet John Dryden adapted the tale into more comprehensible modern language under the title of The Cock and the Fox (1700). In 2007, the playwright Dougie Blaxland wrote a comic verse play Chauntecleer and Pertelotte, roughly based on the Nun's Priest's Tale.

Barbara Cooney's adaptation for children with her own illustrations, Chanticleer and the Fox, won the Caldecott Medal in 1959. Another illustrated edition of the tale won the 1992 Kerlan Award. This was Chanticleer and the Fox – A Chaucerian Tale (1991), written by Fulton Roberts with Marc Davis' drawings for a Disney cartoon that was never completed.

Among musical settings have been Gordon Jacob's The Nun's Priest's Tale (1951) and the similarly titled choral setting by Ross Lee Finney. Another American adaptation was Seymour Barab's comic opera Chanticleer. In the UK Michael Hurd set the tale as Rooster Rag, a pop cantata for children (1976).

A full-length musical stage adaptation of The Canterbury Tales, composed of the Prologue, Epilogue, The Nun's Priest's Tale, and four other tales, was presented at the Phoenix Theatre, London on 21 March 1968, with music by Richard Hill & John Hawkins, lyrics by Nevill Coghill, and original concept, book, and direction by Martin Starkie. The Nun's Priest's Tale section was excluded from the original 1969 Broadway production, though reinstated in the 1970 US tour.

See also

Notes

- General

- Goodall, Peter; Greentree, Rosemary; Bright, Christopher, eds. (2009). Chaucer's Monk's Tale and Nun's Priest's Tale : An Annotated Bibliography 1900 to 2000. annotated by Geoffrey Cooper... et al. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-80209-320-2.

- Specific

- Charles W. Eliot, ed. (1909–1914). English Poetry I: From Chaucer to Gray. The Harvard Classics. Vol. XL. New York: P.F. Collier & Son. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "The Nun's Priest's Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue -- An Interlinear Translation". sites.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- "Russell" refers to the fox's russet coat; "daun" is an English form of the Spanish Don

- Coulton, G. G. (2012). The Medieval Village. Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486158600.

- Mennell, Stephen (1996). All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252064906.

- The Playwrights Database

- English Writers: A Bibliography, New York 2004, p.185

- Sheet music details

- Details online

- Details online

- "Chaucer's Monk's Tale and Nun's Priest's Tale : An Annotated Bibliography 1900 to 2000 / edited by Peter Goodall; annotations by Geoffrey Cooper... et al., editorial assistants, Rosemary Greentree and Christopher Bright". Trove. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

This annotated bibliography is a record of all editions, translations, and scholarship written on The Monk's Tale and the Nun's Priest's Tale in the twentieth century with a view to revisiting the former and creating a comprehensive scholarly view of the latter

.

External links

- Read "The Nun's Priest's Tale" with interlinear translation, Harvard Univ.

- https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/English/CanterburyTalesXVI.php Modern Translation of the Nun's Priest's Tale at Poetry in Translation

- "The Nun's Priest's Tale" – a prose retelling for non-scholars

- Luminarium resources

| Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales | |

|---|---|

| Order of The Canterbury Tales |

|

| Addenda | |

| Films |

|

| Stage and music |

|

| Television |

|

| Literature | |

| Single tale derivations | |

| Related | |

| The Reynard cycle | |

|---|---|

| Reynard cycle |

|

| Adaptations |

|

| Other | |