Breed of cat

| Persian cat | |

|---|---|

Modern-type Persian cat Modern-type Persian cat | |

Traditional-type Persian Traditional-type Persian | |

| Other names | Persian Longhair, Shirazi |

| Origin | |

| Breed standards | |

| CFA | standard |

| FIFe | standard |

| TICA | standard |

| WCF | standard |

| FFE | standard |

| ACF | standard |

| ACFA/CAA | standard |

| CCA-AFC | standard |

| GCCF | standard |

| LOOF | standard |

| Notes | |

| The Exotic Shorthair and Himalayan cats are often classified as coat variants of this breed. | |

| Domestic cat (Felis catus) | |

The Persian cat, also known as the Persian Longhair, is a long-haired breed of cat characterised by a round face and short muzzle. The first documented ancestors of Persian cats might have been imported into Italy from Khorasan as early as around 1620, but this has not been proven. Instead, there is stronger evidence for a longhaired cat breed being exported from Afghanistan and Iran/Persia from the 19th century onwards. Persian cats have been widely recognised by the North-West European cat fancy since the 19th century, and after World War II by breeders from North America, Australia and New Zealand. Some cat fancier organisations' breed standards subsume the Himalayan and Exotic Shorthair as variants of this breed, while others generally treat them as separate breeds.

The selective breeding carried out by breeders has allowed the development of a wide variety of coat colours, but has also led to the creation of increasingly flat-faced Persian cats. Favoured by fanciers, this head structure can bring with it several health problems. As is the case with the Siamese breed, there have been efforts by some breeders to preserve the older type of cat, the Traditional Persian, which has a more pronounced muzzle. Hereditary polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is prevalent in the breed, affecting almost half of the population in some countries.

In 2021, Persian cats were ranked as the fourth-most popular cat breed in the world according to the Cat Fanciers' Association, an American international cat registry.

History

Origin

The exact time of the appearance of long-haired cats is unclear, as no long-haired specimens of the African wildcat, the ancestor of the domestic species, are known.

The first documented ancestors of the Persian cat might have been imported from Khorasan, either Eastern Iran or Western Afghanistan, into the Italian Peninsula in 1620 by Pietro Della Valle; and from Damascus, Syria, into France by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc at around the same time. While the de Peiresc import from Syria is corroborated by later correspondences, Della Valle is only known to have voiced his intention in a letter from 1620 but returned to Italy much later in 1626 after travelling several other countries with the remains of his wife in tow and no further mention of the cats.

In his letter from 1620, Della Valle distinguishes the Khorasan cat from similar long-haired cats imported to Europe from the Near East by their grey coat:

At this point I have found in this country a very beautiful species of cats which are native to the province of Khorasan, but of another appearance and quality than those of Tyre . We estimate them to be of high value; however, they mean nothing to the people of Khorasan. I am inclined to bring them to Rome and to populate Italy with this breed. Their size and their form are like those of ordinary cats. All their beauty is in their coat which is gray without any speckles and without any spots, of one color throughout all the body, being a little lighter on the chest and the stomach which goes somewhat whitish, with an agreeable shade of light brown, as in paintings when one color is mixed with the other to give a marvelous effect.

Albeit of unclear geographic faithfulness, the name Persian cat was eventually given to cats imported from Afghanistan, Iran, and likely some adjacent regions for marketing purposes in Europe. Persian-speakers themselves are not documented to refer to any breed of cat as "Persian cat", or gorba-ye pârsi. Instead, variations of gorbe-ye borāq, gorbe-ye barrāq, and gorbe-ye barāq appear in Persian dictionaries of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 1815, Lord Elphinstone described the cats in Kabul thus:

The cats must also be noticed, at least the longhaired species called Boorauk, as they are exported in great numbers, and everywhere called Persian cats, though they are not numerous in the country from which they are named, and are seldom or never exported thence.

In 1839 Lieutenant Irwin notes that “a variety of cat is bred in Cabul, and some parts of Toorkistan. By us it is very improperly called "Persian", for very few are found in Persia, and none exported. The Cabulees call this cat bubuk or boorrak, and they encourage the growth of his long hair by washing it with soap and combing it.”

Seeing as the British seemed to assume the majority of Persian cats stemmed from Afghanistan, there is reason to infer that no small portion of the original Persian cat breed stock was, among other places, imported from Afghanistan to Britain and other European countries.

However, the Persian cat was not only exported to Europe by this time but also to India. In 1885 Edward Balfour describes the Afghan trade of long-haired cats to India: “The long silky-furred Angora cats are annually brought to India for sale from Afghanistan, with caravans of camels, even so far as Calcutta.”

Similarly in 1882, Jane Dieulafoy, travelling in Iran from Isfahan to Shiraz in a caravan heading for Bušehr, observes “an inhabitant of Yezd in Kirmania, who transported from Tauris to Bombay about twenty beautiful angoras. For several years he constantly travelled between Persia and India and apparently profited from his strange commerce”.

Genetic origin

Recent genetic research indicates that present-day Persian cats are related not to cat breeds from the Near East, but to those from Western Europe, with researchers stating that "Even though the early Persian cat may have in fact originated from Persia, the modern Persian cat has lost its phylogeographical signature".

This can be seen in the phylogenetic tree of cat breeds and populations. The Persian cat is depicted in red, which indicates it falls genetically in the European cat population. The modern-day Persian cat breed is genetically closest related to the British Shorthair, Chartreux, and American Shorthair. The Exotic Shorthair is a breed developed in the late 1950s by outcrossing Persian cats with American Shorthairs.

Development

Persians and Angoras

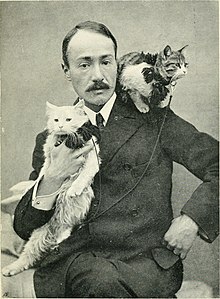

Historical Persian cat show winners

Top: Blue Persian, prize-winner at Westminster (1899)

Top: Blue Persian, prize-winner at Westminster (1899)Middle: Silver Persian, winner of multiple leading cat shows in the UK (1902)

Bottom: French blue Persian with a more ultra-type face, winner of a cat show in the Netherlands (1964)

A Persian cat was presented at the first organised cat show, in 1871 in The Crystal Palace in London, England, organized by Harrison Weir. As specimens closer to the later established Persian conformation became the more popular types, attempts were made to differentiate it from the Angora. The first breed standard (then called the points of excellence list) was issued in 1889 by cat show promoter Weir. Weir stated that the Persian differed from the Angora in the tail being longer, hair more full and coarse at the end, and head larger, with less pointed ears. Not all cat fanciers agreed with the idea of making (or creating) a distinction between the two types, and in The Book of the Cat of 1903, Francis Simpson states that "the distinctions, apparently with hardly any difference, between Angoras and Persians are of so fine a nature that I must be pardoned if I ignore the class of cat commonly called Angora".

Dorothy Bevill Champion lays out the difference between the two types in the 1909 Everybody's Cat Book:

Our pedigree imported long-hairs of to-day are undoubtedly a cross of the Angora and Persian; the latter possesses a rounder head than the former, also the coat is of quite a different quality.

Bell goes on to detail the differences. Persian coats consist of a woolly undercoat and a long, hairy outer coat. The coat loses all the thick underwool in the summer, and only the long hair remains. Hair on the shoulders and upper part of the hind legs is somewhat shorter. Conversely, the Angora has a very different coat which consists of long, soft hair, hanging in locks, "inclining to a slight curl or wave on the under parts of the body." The Angora's hair is much longer on the shoulders and hind legs than the Persian, which Bell considered a great improvement. However, Bell says the Angora "fails to the Persian in head", Angoras having a more wedge-shaped head and Persians having a rounder head.

Bell notes that Angoras and Persians have been crossbred, resulting in a decided improvement to each breed, but claimed the long-haired cat of 1909 had significantly more Persian influence than Angora.

Champion lamented the lack of distinction among various long-haired types by English fanciers, who in 1887, decided to group them under the umbrella term "Long-haired Cats".

Traditional Persian

The traditional Persian, doll-face Persian, or moon-face Persian are somewhat recent names for a variety of the Persian breed, which is essentially the original phenotype of the Persian cat, without the development of extreme features.

As many breeders in the United States, Germany, Italy, and other parts of the world started to interpret the Persian standard differently, they developed the flat-nosed "peke-face" or "ultra-type" over time, as the result of two genetic mutations, without changing the name of the breed from "Persian". Some organisations, including the Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA), consider the peke-face type as their modern standard for the Persian breed. Thus the retronym Traditional Persian was created to refer to the original type, which is still bred, mirroring the renaming of the original-style Siamese cat as the Traditional Siamese or Thai, to distinguish it from the long-faced modern development which has taken over as simply "the Siamese".

Not all cat fancier groups recognise the Traditional Persian (at all, or as distinct), or give it that specific name. TICA has a very general standard that does not specify a flattened face.

Modern Persian (peke-face and ultra-typing)

A Persian with a visible muzzle in contrast with a Persian with its forehead, nose and chin in vertical alignment, as called for by CFA's 2007 breed standard. The shorter the muzzle, the higher the nose tends to be. UK standards penalise Persians whose nose leather extends above the bottom edge of the eye.

A Persian with a visible muzzle in contrast with a Persian with its forehead, nose and chin in vertical alignment, as called for by CFA's 2007 breed standard. The shorter the muzzle, the higher the nose tends to be. UK standards penalise Persians whose nose leather extends above the bottom edge of the eye.

In the late 1950s, a spontaneous mutation in red tabby Persians gave rise to the "peke-faced" Persian, named after the flat-faced Pekingese dog. It was registered as a distinct breed in the CFA, but fell out of favour by the mid-1990s due to serious health issues; only 98 were registered between 1958 and 1995. Despite this, breeders took a liking to the look and started breeding towards the peke-face look. The over-accentuation of the breed's characteristics by selective breeding (called extreme- or ultra-typing) produced results similar to the peke-faced Persians. The term peke-face has been used to refer to the ultra-typed Persian but it is properly used only to refer to red tabby Persians bearing the mutation. Many fanciers and CFA judges considered the shift in look "a contribution to the breed."

In 1958, breeder and author P. M. Soderberg wrote in Pedigree Cats, Their Varieties, breeding and Exhibition:

Perhaps in recent times there has been a tendency to over-accentuate this type of short face, with the result that a few of the cats seen at shows have faces which present a peke-like appearance. This is a type of face which is definitely recognized in the United States, and helps to form a special group within the show classification for the breed. There are certainly disadvantages when the face has become too short, for this exaggeration of type is inclined to produce a deformity of the tear ducts, and running eyes may be the result. A cat with running eyes will never look at its best because in time the fur on each side of the nose becomes stained, and thus detracts from the general appearance .... The nose should be short, but perhaps a plea may be made here that the nose is better if it is not too short and at the same time uptilted. A nose of this type creates an impression of grotesqueness which is not really attractive, and there is always a danger of running eyes.

While the looks of the Persians changed, the Persian Breed Council's standard for the Persians remained the same. The Persian breed standard is, by its nature, somewhat open-ended and focused on a rounded head, large, wide-spaced round eyes with the top of the nose in alignment with the bottom of the eyes. The standard calls for a short, cobby body with short, well-boned legs, a broad chest, and a round appearance, everything about the ideal Persian cat being "round". It was not until the late 1980s that standards were changed to limit the development of the extreme appearance. In 2004, the statement that muzzles should not be overly pronounced was added to the breed standard. The standards were altered yet again in 2007, this time to reflect the flat face, and it now states that the forehead, nose, and chin should be in vertical alignment.

In the UK, the standard was changed by the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) in the 1990s to disqualify Persians with the "upper edge of the nose leather above the lower edge of the eye" from Certificates or First Prizes in Kitten Open Classes.

While ultra-typed cats do better in the show ring, the public seems to prefer the less extreme, older "doll-face" types.

Variants

Himalayan

Main article: Himalayan cat

In 1950, the Siamese was crossed with the Persian to create a breed with the body type of the Persian but the colorpoint pattern of the Siamese. It was named Himalayan, after other colorpoint animals such as the Himalayan rabbit. In the UK, the breed was recognized as the Colorpoint Longhair. The Himalayan stood as a separate breed in the US until 1984, when the CFA merged it with the Persian, to the objection of the breed councils of both breeds. Some Persian breeders were unhappy with the introduction of this crossbreed into their "pure" Persian lines.

The CFA set up the registration for Himalayans in a way that breeders would be able to discern a Persian with Himalayan ancestry just by looking at the pedigree registration number. This was to make it easy for breeders who do not want Himalayan blood in their breeding lines to avoid individuals who, while not necessarily exhibiting the colourpoint pattern, may be carrying the point colouration gene recessively. Persians with Himalayan ancestry have registration numbers starting with 3 and are commonly referred to by breeders as colourpoint carriers (CPC) or 3000-series cats, although not all will carry the recessive gene. The Siamese is also the source of the chocolate and lilac colour in solid Persians.

Exotic Shorthair

Main article: Exotic Shorthair

The Persian was used as an outcross secretly by some American Shorthair (ASH) breeders in the late 1950s to "improve" their breed. The crossbreed look gained recognition in the show ring, but other breeders unhappy with the changes successfully pushed for new breed standards that would disqualify ASH that showed signs of crossbreeding.

One ASH breeder who saw the potential of the Persian/ASH cross proposed, and eventually managed, to get the CFA to recognize them as a new breed in 1966, under the name Exotic Shorthair. Regular outcrossing to the Persian has made present-day Exotic Shorthair similar to the Persian in every way, including temperament and conformation, except for the short dense coat. It has even inherited much of the Persian's health problems. The easier-to-manage coat has made some label the Exotic Shorthair "the lazy man's Persian".

Because of the regular use of Persians as outcrosses, some Exotics may carry a copy of the recessive longhair gene. When two such cats mate, there is a one in four chance of each offspring being longhaired. Longhaired Exotics are not considered Persians by CFA, although The International Cat Association accepts them as Persians. Other associations register them as a separate Exotic Longhair breed.

Chinchilla Longhair

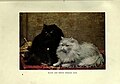

Two black silver chinchilla Persians Traditional

Traditional Modern

Modern

Originating in England in 1882 by accident, a silver tabby and smoke-coloured Persian offspring produced Silver Lambkin, a cat regarded as the father of the chinchilla Persian line. Silver Lambkin was bred, and even members of the British royal family had his descendants.

In the US, there was an attempt to establish the silver Persian as a separate breed called the Sterling, but it was not accepted. Silver and golden Persians are recognized, as such, by CFA. In South Africa, the attempt to separate the breed was more successful; the Southern Africa Cat Council (SACC) registers cats with five generations of purebred Chinchilla as a Chinchilla Longhair. The Chinchilla Longhair has a slightly longer nose than the Persian, resulting in healthy breathing and less eye tearing. Its hair is translucent with only the tips carrying black pigment, a feature that gets lost when out-crossed to other coloured Persians. Out-crossing also may result in losing nose and lip liner, which is a fault in the Chinchilla Longhair breed standard. One of the distinctions of this breed is the blue-green or green eye colour only with kittens having blue or blue-purple eye colour.

Registration

Classification by registries

The breed standards of various cat fancier organisations may treat the Himalayan and Exotic Shorthair (or simply Exotic) as variants of the Persian or as separate breeds. The Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA) treats the Himalayan as a colour-pattern class of both the Persian and the Exotic, which have separate but nearly identical standards (differing in coat length). The Fédération Internationale Féline (FIFe) entirely subsumes what other registries call the Himalayan as simply among the allowed colouration patterns for the Persian and the Exotic, treated as separate breeds. The International Cat Association (TICA) treats them both as variants of the Persian. The World Cat Federation (WCF) treats the Persian and Exotic Shorthair as separate breeds and subsumes the Himalayan colouration as colourpoint varieties under each.

Among regional and national organizations, Feline Federation Europe treats all three as separate breeds. The American Cat Fanciers Association (ACFA) has the three as separate breeds (also with a Non-pointed Himalayan that is similar to the Persian). The Australian Cat Federation (AFC) follows the FIFe practice. The Canadian Cat Association (CCA-AFC) treats the three separately and even has an Exotic Longhair sub-breed of the Exotic and a Non-pointed Himalayan sub-breed of the Himalayan, which differ from the Persian only in having some mixed ancestry. The (UK) Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) does likewise.

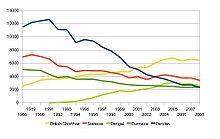

Popularity

In 2008, the Persian was the most popular breed of pedigree cats in the United States. In the UK (GCCF), registration numbers have decreased since the early 1990s and the Persian lost its top spot to the British Shorthair in 2001. As of 2012, it was the 6th most popular breed, behind the British Shorthair, Ragdoll, Siamese, Maine Coon and Burmese. In France, the Persian is the only breed whose registration declined between 2003 and 2007, dropping by more than a quarter.

The most colour popular varieties, according to CFA registration data, are seal point, blue point, flame point and tortie point Himalayan, followed by black-white, shaded silvers and calico.

Characteristics

Appearance

A show-style Persian cat has an extremely long and thick coat, short legs, a wide head with ears set far apart, large eyes, and an extremely shortened muzzle. The breed was originally established with a short muzzle, but over time, this characteristic has become extremely exaggerated, particularly in North America. Persian cats can have virtually any colour or markings.

Colouration

The permissible colours in the breed, in most organisations' breed standards, encompass the entire range of cat coat-pattern variations.

The International Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA) groups the breed into four coat-pattern divisions, but differently: solid, silver and golden (including chinchilla and shaded variants, and blued subvariants), shaded and smoke (with several variations of each, and a third sub-categorisation called shell), tabby (only classic, mackerel, and patched , in various colours), party-colour (in four classes, tortoiseshell, blue-cream, chocolate tortie, and lilac-cream, mixed with other colours), calico and bi-colour (in around 40 variations, broadly classified as calico, dilute calico, and bi-colour), and Himalayan (white-to-fawn body with point colouration on the head, tail and limbs, in various tints).

CFA base colours are white, black, blue, red, cream, chocolate, and lilac. There are around 140 named CFA coat patterns for which the Himalayan qualifies, and 20 for the Himalayan sub-breed. These coat patterns encompass virtually all of those recognised by CFA for cats generally. Any Persian permissible in TICA's more detailed system would probably be accepted in CFA's, simply with a more general name, though the organisations do not mix breed registries.

The International Cat Association (TICA) groups the breed into three coat-pattern divisions for judging at cat shows traditional (with stable, rich colours), sepia ("paler and warmer than the traditional equivalents", and darkening a bit with age), and mink (much lighter than sepia, and developing noticeably with age on the face and extremities). If classified as the Himalayan sub-breed, full point colouration is required, the fourth TICA colour division, with a "pale and creamy coloured" body even lighter than mink, with intense colouration on the face and extremities. The four TICA categories are essentially a graduated scale of colour distribution from evenly coloured to mostly coloured only at the points. Within each, the colouration may be further classified as solid, tortoiseshell (or "tortie"), tabby, silver or smoke, solid-and-white, tortoiseshell-and-white, tabby-and-white, or silver/smoke-and-white, with various specific colours and modifiers (e.g. chocolate tortoiseshell point, or fawn shaded mink marbled tabby-torbie).

TICA-recognised tabby patterns include classic, mackerel, marbled, spotted, and ticked (in two genetic forms), while other patterns include shaded, chinchilla, and two tabby-tortie variations, golden, and grizzled. Basic colours include white, black, brown, ruddy, bronze, blue ("grey"), chocolate, cinnamon, lilac, fawn, red, and cream, with a silver or shaded variant of most. Not counting bi-colour (piebald) or party-colour coats, nor genetically impossible combinations, there are nearly 1,000 named coat pattern variations in the TICA system for which the Persian/Himalayan qualifies. The Exotic Shorthair sub-breed qualifies for every cat coat variation that TICA recognises.

Eye colours range widely and may include blue, copper, odd-eyed blue and copper, green, blue-green, and hazel. Various TICA and CFA coat categorisations come with specific eye-colour requirements.

Behaviour

The Persian is generally described as a quiet cat. Typically placid, it adapts quite well to apartment life. Himalayans tend to be more active due to the influence of Siamese traits. In a study comparing cat owners' perceptions of their cats, Persians rated higher than non-pedigree cats on closeness and affection to owners, friendliness towards strangers, cleanliness, predictability, vocalization, and fussiness over food.

Health

Ultra-type consequences

The modern-type brachycephalic Persian has a large rounded skull and shortened face and nose. This facial conformation makes the breed prone to breathing difficulties, skin and eye problems, and birthing difficulties. Anatomical abnormalities associated with brachycephalic breeds can cause shortness of breath. Persians are susceptible to malocclusion (incorrect bite), which can affect their ability to grasp, hold and chew food. Even without the condition, the flat face of the Persian can make picking up food difficult, so much so that specially shaped kibble has been created by pet food companies to cater to the Persian.

Malformed tear ducts cause epiphora, an overflow of tears onto the face, which is common but primarily cosmetic. Entropion, the inward folding of the eyelids, causes the eyelashes to rub against the cornea and can lead to tearing, pain, infection and cornea damage. This condition is not uncommon in Persians and usually involves the medial aspect of the lower eyelid. Similarly, in upper-eyelid trichiasis or nasal-fold trichiasis, eyelashes/hair from the eyelid and hair from the nose fold near the eye grow in a way that rubs against the cornea.

The anatomical changes in the upper respiratory track caused by brachycephaly such as stenotic nares, elongated soft palate, and nasopharyngeal turbinates contribute to obstruction of the airways and breathing difficulties. Due to the reduction of the maxillary alveolar space the Persian's teeth are positioned at abnormal angles and overlap, causing dental and gingival problems. Brachcephaly causes the Persian to have shallow orbits and protuding eyes, this can lead to keratitis, sequestrum developments in the cornea, and non-healing corneal ulcers. The reduction of the length of the maxilla can cause excessive skin folds on the face, which may lead to the development of idiopathic facial dermatitis. The brachcephalic skull of the Persian has led to changes in the morphology of the cranial cavity, causing intracranial overcrowding, herniation of the brain, and hydrocephaly.

Dystocia, an abnormal or difficult labour, is relatively common in Persians. Consequently, the stillbirth rate is higher than normal, ranging from 16.1% to 22.1%, and one 1973 study puts the kitten mortality rate (including stillborns) at 29.2%. A veterinary study in 2010 documented the serious health problems caused by the brachycephalic head.

Life span

Pet insurance data from Sweden puts the median lifespan of cats from the Persian group (Persians, Chinchilla, Himalayan and Exotic) at just above 12.5 years, while most cats live until they are about 15 years old. 76% of this group lived for 10 years or more and 52% lived for 12.5 years or more. A 2015 study looking at veterinary clinic data from England shows an average lifespan of 14.1. A 2024 UK study found a life expectancy of 10.93 years for the Persian compared to an overall of 11.74 years.

Internal medical conditions

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) which causes kidney failure in affected adult cats has an incidence rate of 36–49% in the Persian breed. A study in Japan of cats suspected to have kidney problems found that 46% of tested Persian cats had the PKD1 mutation, which is responsible for feline polycystic kidney disease (PKD). Previous ultrasonographic studies (involving procedures likely to be performed on cats suspected of kidney problems) found a PKD rate in Persian and related breeds of 49.2% in the UK, 43% in Australia, and 41.8% in France. The cause of PKD in the Persian is an autosomal dominant mutation to the PKD1 gene.

Cysts develop and grow in the kidney over time, replacing kidney tissues and enlarging the kidney. Kidney failure develops later in life, at an average age of 7 years old (ranging from 3 to 10 years old). Symptoms include excessive drinking and urination, reduced appetite, weight loss, and depression. The disease is autosomal dominant and DNA screening is the preferred method of eliminating the gene in the breed. Because of DNA testing, most responsible Persian breeders now have cats that no longer carry the PKD gene, hence their offspring also do not have the gene. Before DNA screening was available, an ultrasound was done. However, an ultrasound is only as good as the day that it is done, and many cats that were thought to be clear, were in fact, a carrier of the PKD gene. Only DNA screening and breeding cats that are negative for the PKD gene will produce kittens that are also negative for the gene, effectively removing this gene from the breeding pool.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common heart disease in all cats. It is likely hereditary in the Persians. The disease causes thickening of the left heart chamber, which can, in some instances, lead to sudden death. It tends to affect males and mid- to old-aged individuals. The reported incidence rate in Persians is 6.5%. Unlike PKD, which can be detected even in very young cats, heart tests for HCM have to be done regularly to effectively track and/or remove affected individuals and their offspring from the breeding pool.

Early onset progressive retinal atrophy is a degenerative eye disease, with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance in the Persian. Despite a belief among some breeders that the disease is limited to chocolate and Himalayan lines, there is no apparent link between coat colour in Persians and the development of PRA. Basal-cell carcinoma is a skin cancer which shows most commonly as a growth on the head, back or upper chest. While often benign, rare cases of malignancy tend to occur in Persians. Blue smoke Persians are predisposed to Chédiak–Higashi syndrome. White cats, including white Persians, are prone to deafness, especially those with blue eyes.

Skeletal conditions

A study of cats presented to the University of Missouri-Columbia Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital that underwent radiography found 3 Persians out of a population of 19 to have hip dysplasia, higher than the 6.6% average for all cats.

Other

Other conditions which the Persian is predisposed to are listed below:

- Dermatological – primary seborrhoea, idiopathic periocular crusting, dermatophytosis (ringworm), facial fold pyoderma, idiopathic facial dermatitis, multiple epitrichial cysts (eyelids)

- Ocular – coloboma, lacrimal punctal aplasia, corneal sequestrum, congenital cataract, excessive tearing, eye condition such as cherry eye

- Urinary – calcium oxalate urolithiasis (feline lower urinary tract disease)

- Reproductive – cryptorchidism

- Gastrointestinal – congenital portosystemic shunt, congenital polycystic liver disease (associated with PKD)

- Cardiovascular – peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia

- Immunological – systemic lupus erythematosus

- Neurological – alpha-mannosidosis

- Neoplastic – basal-cell carcinoma, sebaceous gland tumours

- Drug sensitivity — Persians are more prone to side effects of ringworm drug Griseofulvin.

- Heat sensitivity

Idiopathic facial dermatitis

Idiopathic facial dermatitis, also known as facial dermatitis of the Persian and Himalayan cat is a type of dermatitis only observed in the Persian and Himalayan cat. It's characterised by greasy skin, debris adhering to the folds of the face and nose, ceruminous otitis externa, secondary bacterial folliculitis and Malassezia dermatitis, and pruritus. Onset is at 10 months to 6 years.

Breeding ethics

Persian cats, known for their facial structure, raise concerns about the ethics of breeding for certain deformities.

Brachycephaly is a highly sought-after characteristic producing big owl-like eyes and an overall petite-looking face. Though these features may be "cuter", they result in many health issues including ill-functioning nasolacrimal systems where tears build and flow down the face, a soft and long palate that obstructs the upper airway making breathing more difficult, and dental and jaw defects (brachygnathia) where the teeth grow outwardly in unnatural positions, making it difficult to eat and increasing the chance of plaque formation gingivitis.

Such health issues affect the quality of life of many Persian cats, especially those that fall into the severe category, and raise questions about the ethics and legality of these deformity breeding programmes.As a consequence of the BBC programme Pedigree Dogs Exposed, cat breeders have also come under pressure from veterinary and animal welfare associations, with the Persian singled out as one of the breeds most affected by health problems. Animal welfare proponents have suggested changes to breed standards to prevent diseases caused by over- or ultra-typing, and prohibiting the breeding of animals outside the set limits. Apart from the GCCF standard that limits high noses, TICA, and FIFe standards require nostrils to be open, with FIFe stating that nostrils should allow "free and easy passage of air." Germany's Animal Welfare Act also prohibits the breeding of brachycephalic cats in which the tip of the nose is higher than the lower eyelids.

Grooming

Since Persian cats have long, dense fur that they cannot effectively keep clean, they need regular grooming to prevent matting. To keep their fur in its best condition, they must be brushed frequently. An alternative is to shave the coat. Their eyes may require regular cleaning to prevent crust buildup and tear staining.

Persian cats in art

The art world and its patrons have long embraced their love for the Persian cat by immortalizing them in art. A 1.8 m × 2.6 m (6 ft × 8.5 ft) artwork that is purported to be the "world's largest cat painting" sold at auction for more than US$820,000. The late 19th-century oil portrait is called My Wife's Lovers, and it once belonged to a wealthy philanthropist who commissioned an artist to paint her vast assortment of Turkish Angoras and Persians. Other popular Persian paintings include White Persian Cat by famous folk artist Warren Kimble and Two White Persian Cats Looking into a Goldfish Bowl by late feline portraitist Arthur Heyer. The Persian cat has made its way onto the artwork of stamps around the world.

-

My Wife's Lovers (1891), Carl Kahler. Painting featuring Persian and Angora cats sold for more than US$820,000 at Sotheby's.

My Wife's Lovers (1891), Carl Kahler. Painting featuring Persian and Angora cats sold for more than US$820,000 at Sotheby's.

-

The book of the cat (Plate 2) featuring a solid black and a solid white Persian cat

The book of the cat (Plate 2) featuring a solid black and a solid white Persian cat

-

The book of the cat (Plate 5) featuring a smoke and a red Persian

The book of the cat (Plate 5) featuring a smoke and a red Persian

-

Stamps of Azerbaijan featuring a Persian Tabby kitten

Stamps of Azerbaijan featuring a Persian Tabby kitten

-

The book of the cat (Plate 6) featuring a tortoiseshell and a calico Persian cat

The book of the cat (Plate 6) featuring a tortoiseshell and a calico Persian cat

References

- Ibrahim, Alaa; Nomeir, Ahmed; Emara, Doaa; El Sharaby, Ashraf (September 1, 2021). "Comparative pilot study of radiography and computed tomography for the thorax of Shirazi cat". Damanhour Journal of Veterinary Sciences. 6 (2): 1–6. doi:10.21608/djvs.2021.79115.1037. ISSN 2636-3011.

- ^ Digard, Jean-Pierre. "CAT II. Persian Cat". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- Floor, Willem (2023). "A Note on Persian Cats". Iranian Studies. 36. Carfax Publishinh: 27–42. doi:10.1080/021086032000062866A. S2CID 161381713. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- "Persian Cat Information | Persian Cat Corner". Persian Cat Resource. February 13, 2017.

- ^ Baggaley, Ann; Goddard, Jolyon; John, Katie (2014). The cat encyclopedia - the definitive visual guide (First American ed.). London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 9781465419590. OCLC 859882932.

- "Polycystic kidney disease". International Cat Care. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Polycystic Kidney Disease". www.vet.cornell.edu. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "The Cat Fanciers' Association Announces Most Popular Breeds for 2020". cfa.org. February 25, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- Grey, Edward. "The Travels of Pietro Della Valle in India, Volume I". Famine and Dearth in India and Britain 1550-1800. Hakluyt Society. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- Freund and Yonan (April 4, 2019). "Cats: The Soft Underbelly of the Enlightenment," Journal18 Issue 7 Animals (Spring 2019)". Journal18. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- Naficy, 1967, p. 68; Haïm, 1969, I, p. 244.

- Steingass, 1892: 1078.

- Elphinstone, Mountstuart (1842). An account of the kingdom of Caubul, and its dependencies, in Persia, Tartary, and India (1842) - Volume I. University of Nebraska Omaha. p. 191.

- Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (1903). Across coveted lands : or, A journey from Flushing (Holland) to Calcutta, overland. University of California Libraries. New York : C. Scribner's sons.

- Irwin, Lieut. (1839). "Memoir on the Climate, Soil, Produce and Husbandry of Afghanistan and the Neighbouring Countries, Part III, Section III: Of Animals". Journal of TheAsiatic Society of Bengal. 8: 1007. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Lipinski, Monika J.; Froenicke, Lutz; Baysac, Kathleen C.; Billings, Nicholas C.; Leutenegger, Christian M.; Levy, Alon M.; Longeri, Maria; Niini, Tirri; Ozpinar, Haydar; Slater, Margaret R.; Pedersen, Niels C.; Lyons, Leslie A. (January 2008). "The Ascent of Cat Breeds: Genetic Evaluations of Breeds and Worldwide Random Bred Populations". Genomics. 91 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.10.009. PMC 2267438. PMID 18060738.

- Helgren, J. Anne. (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Persian Cats". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Weir, Harrison (1889). Our Cats and All About Them. Tunbridge Wells, UK: R. Clements & Co. LCCN 2002554760. OL 3664970M. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Simpson, Frances. (1903). The Book of the Cat. London/New York: Cassell and Company. p. 98. LCCN 03024964. OL 7205700M. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Champion, Dorothy Bevill (1909). Everybody's Cat Book. New York: Lent & Graff. p. 17. LCCN 10002159. OCLC 8291178. OL 7015748M. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Helgren, J. Anne (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Turkish Angora". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "Cats and Kittens: Maine coon Kittens". Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ "Persian Breed Group" (PDF). TICA.org. Harlingen, Texas: The International Cat Association. May 1, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Hartwell, Sarah (2013). "Longhaired Cats". Messybeast Cats. Sarah Hartwell. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Saunders, Lorraine (November 2002). "Solid Color Persians Are...Solid As a Rock?". Cat Fanciers' Almanac. Cat Fanciers' Association. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Brocato, Judy; Brocato, Greg (March 1995). "Stargazing: A Historical View of Solid Color Persians". Cat Fanciers' Almanac. Cat Fanciers' Association. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Hartwell, Sarah (2010). "Novelty Breeds and Ultra-Cats – A Breed Too Far?". Messybeast Cats. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Shaun (July 17, 2018). "Why Do Persian Cats Look Angry?". Persian Cat Corner. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "2003 Breed Council Ballot Proposals and Results". CFA Persian Breed Council. 2004. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- "2006 Breed Council Ballot Proposals and Results". CFA Persian Breed Council. 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- Bi-Color and Calico Persians: Past, Present and Future Archived August 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Cat Fanciers' Almanac. May 1998

- ^ "Persian Section" (PDF). GCCFCats.org. Governing Council of the Cat Fancy. 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Helgren, J. Anne. (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Himalayan". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Breed Article: Himalayan-Persian "CFA Breed Article: Himalayan - Persian". Archived from the original on September 13, 2009. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Cat Fanciers' Almanac May 1999 - Breed Profile: Persian – Solid Color Division Archived September 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Cat Fanciers' Association

- "CFA ANNUAL AND EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETINGS JUNE 23–27, 2004" (PDF). cfainc.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2010.

- Helgren, J. Anne. (2006). "Cat Breed Detail: Exotic Shorthair". Iams.com. Telemark Productions / Procter & Gamble. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "Chinchilla Persian Cat: Breed Profile, Characteristics, and Care Guide – BuzzPetz". December 16, 2022.

- Difference Between Chinchilla Rodent and Chinchilla Cat Archived July 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Chinchillafactssite.com

- ^ "Persian Show Standard" (PDF). CFAInc.com. Alliance, Ohio: Cat Fanciers' Association. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "Category I: Exotic/Persian" (PDF). FIFeweb.org. Jevišovkou, Czech Republic: Fédération Internationale Féline. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "Breed Standards: Persian–Colourpoint" (PDF). WCF-Online.de. Essen, Germany: World Cat Federation. January 1, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "British Shorthair and Highlander". Bavarian-CFA.de. Feline Federation Europe. September 25, 2004. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015. Note: Due to poor coding at this site, this link goes directly to the standard's content.

- "Persian" (PDF). ACFACat.com. Nixa, Missouri: American Cat Fanciers' Association. May 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "ACF Standards: Persian [PER]" (PDF). Canning Vale, Western Au.: Australian Cat Federation. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "Persian" (PDF). CCA-AFC.com. Mississauga, Ontario: Canadian Cat Federation. August 6, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2015. Also referred to corresponding Exotic Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine and Himalayan Archived October 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine standards.

- ^ 2008 Top Pedigreed Breeds Archived April 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine CFA. March 2009.

- "Analysis of Breeds Registered" (PDF). Governing Council of the Cat Fancy. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- Javerzac, Anne-marie (2008). "Palmarès du chat de race en France: Les données 2008 du LOOF" (in French). ANIWA. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008.

- "Uniform Color Descriptions and Glossary of Terms" (PDF). The International Cat Association. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- Turner, D. C. (2000). "Human-cat interactions: relationships with, and breed differences between, non-pedigree, Persian and Siamese cats". In Podberscek, A. L.; Paul, E. S.; Serpell, J. A. (eds.). Companion Animals & Us: Exploring the Relationships Between People & Pets. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 257–271. ISBN 978-0-521-63113-6.

- Künzel, W.; Breit, S.; Oppel, M. (2003). "Morphometric Investigations of Breed-Specific Features in Feline Skulls and Considerations on their Functional Implications". Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 32 (4): 218–223. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0264.2003.00448.x. PMID 12919072. S2CID 2721559.

- ^ Cat Owner's Home Veterinary Handbook

- Persian 30 Royal Canin

- ^ Gelatt, Kirk N.; Ben-Shlomo, Gil; Gilger, Brian C.; Hendrix, Diane V. H.; Kern, Thomas J.; Plummer, Caryn E., eds. (2021). Veterinary Ophthalmology (6th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-44181-6. OCLC 1143827380.

- Stades, Frans Cornelis; Wyman, Milton; Boevé, Michael H.; Neumann, Willy; Spiess, Bernhard (2007). Ophthalmology for the Veterinary Practitioner (2nd ed.). Hannover: Schlütersche. ISBN 978-3-89993-011-5.

- Farnworth, Mark J; Chen, Ruoning; Packer, Rowena M. A.; Caney, Sarah M. A.; Gunn-Moore, Danièlle A. (August 30, 2016). "Flat Feline Faces: Is Brachycephaly Associated with Respiratory Abnormalities in the Domestic Cat (Felis catus)?". PLOS ONE. 11 (8). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e0161777. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1161777F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161777. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5004878. PMID 27574987.

- ^ Schmidt, M.J.; Kampschulte, M.; Enderlein, S.; Gorgas, D.; Lang, J.; Ludewig, E.; Fischer, A.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Schaubmar, A.R.; Failing, K.; Ondreka, N. (August 20, 2017). "The Relationship between Brachycephalic Head Features in Modern Persian Cats and Dysmorphologies of the Skull and Internal Hydrocephalus". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 31 (5). Wiley: 1487–1501. doi:10.1111/jvim.14805. ISSN 0891-6640. PMC 5598898. PMID 28833532.

- Croix, Noelle C. La; Woerdt, Alexandra van der; Olivero, Dennis K. (March 1, 2001). "Nonhealing corneal ulcers in cats: 29 cases (1991–1999)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 218 (5). American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA): 733–735. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.218.733. ISSN 0003-1488. PMID 11280407.

- Blocker, Tiffany; Van Der Woerdt, Alexandra (2001). "A comparison of corneal sensitivity between brachycephalic and Domestic Short-haired cats". Veterinary Ophthalmology. 4 (2). Wiley: 127–130. doi:10.1046/j.1463-5224.2001.00189.x. ISSN 1463-5216. PMID 11422994.

- Featherstone, Heidi J.; Sansom, Jane (June 16, 2004). "Feline corneal sequestra: a review of 64 cases (80 eyes) from 1993 to 2000". Veterinary Ophthalmology. 7 (4). Wiley: 213–227. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2004.04028.x. ISSN 1463-5216. PMID 15200618.

- Malik, Richard; Sparkes, Andy; Bessant, Claire (2009). "Brachycephalia - a Bastardisation of what Makes Cats Special". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 11 (11). SAGE Publications: 889–890. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2009.09.009. ISSN 1098-612X. PMC 11383017. PMID 19857851. S2CID 1789486.

- Sieslack, Jana; Farke, Daniela; Failing, Klaus; Kramer, Martin; Schmidt, Martin J. (July 21, 2021). "Correlation of brachycephaly grade with level of exophthalmos, reduced airway passages and degree of dental malalignment' in Persian cats". PLOS ONE. 16 (7): e0254420. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1654420S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254420. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8294563. PMID 34288937.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- Gunn-Moore, D. A.; Thrusfield, M. V. (1995). "Feline dystocia: prevalence, and association with cranial conformation and breed". Vet Rec. 136 (14): 350–353. doi:10.1136/vr.136.14.350 (inactive November 1, 2024). PMID 7610538. S2CID 46646058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Prescott, C. (1973). “Reproduction patterns in the domestic cat.” Aust Vet J 49: 126-129.

- ^ Schlueter, C.; Budras, K. D.; Ludewig, E.; Mayrhofer, E.; Koenig, H. E.; Walter, A.; Oechtering, G. U. (2009). "Brachycephalic feline noses: CT and anatomical study of the relationship between head conformation and the nasolacrimal drainage system" (PDF). Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery. 11 (11): 891–900. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2009.09.010. PMC 11383020. PMID 19857852. S2CID 7762312.

- ^ Egenvall, A.; Nødtvedt, A.; Häggström, J.; Ström Holst, B.; Möller, L.; Bonnett, B. N. (2009). "Mortality of Life-Insured Swedish Cats during 1999—2006: Age, Breed, Sex, and Diagnosis". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 23 (6): 1175–1183. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0396.x. PMC 7167180. PMID 19780926.

- O'Neill, D. G. (2014). "Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England" (PDF). Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 17 (2): 125–33. doi:10.1177/1098612X14536176. PMC 10816413. PMID 24925771. S2CID 7098747. "n=70, median=14.1, IQR 12.0-17.0, range 0.0-21.2"

- Teng, Kendy Tzu-yun; Brodbelt, Dave C; Church, David B; O’Neill, Dan G (2024). "Life tables of annual life expectancy and risk factors for mortality in cats in the UK". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 26 (5): 1098612X241234556. doi:10.1177/1098612X241234556. ISSN 1098-612X. PMC 11156239. PMID 38714312.

- "Polycystic Kidney Disease". Genetic welfare problems of companion animals. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- Sato, R.; Uchida, N.; Kawana, Y.; Tozuka, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Hanyu, N.; Konno, Y.; Iguchi, Aiko; Yamasaki, Yayoi; Kuramochi, Konomi; Yamasaki, Masahiro (2019). "Epidemiological evaluation of cats associated with feline polycystic kidney disease caused by the feline PKD1 genetic mutation in Japan". The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 81 (7): 1006–1011. doi:10.1292/jvms.18-0309. PMC 6656814. PMID 31155548.

- Sato et al. (2019). Citing:

- Cannon, M. J.; MacKay, A. D.; Barr, F. J.; Rudorf, H.; Bradley, K. J.; Gruffydd-Jones, T. J. (October 2001). "Prevalence of polycystic kidney disease in Persian cats in the United Kingdom". Veterinary Record. 149 (14): 409–411. doi:10.1136/vr.149.14.409. PMID 11678212. S2CID 45594692.

- Barrs, V. R.; Gunew, M.; Foster, S. F.; Beatty, J. A.; Malik, R. (April 2001). "Prevalence of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Persian cats and related-breeds in Sydney and Brisbane". Australian Veterinary Journal. 79 (5): 257–259. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2001.tb11977.x. PMID 11349412.

- Barthez, P. Y.; Rivier, P.; Begon, D. (2003). "Prevalence of polycystic kidney disease in Persian and Persian related cats in France". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 5 (6): 345–347. doi:10.1016/S1098-612X(03)00052-4. PMC 10822557. PMID 14623204. S2CID 26271964.

- Oliver, James A.C.; Mellersh, Cathryn S. (2020). "Genetics". In Cooper, Barbara; Mullineaux, Elizabeth; Turner, Lynn (eds.). BSAVA Textbook of Veterinary Nursing (Sixth ed.). British Small Animal Veterinary Association. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-910-44339-2.

- Hosseininejad, M.; Vajhi, A.; Marjanmehr, H.; Hosseini, F. (2008). "Polycystic kidney in an adult Persian cat: Clinical, diagnostic imaging, pathologic, and clinical pathologic evaluations". Comparative Clinical Pathology. 18: 95–97. doi:10.1007/s00580-008-0744-0. S2CID 32052553.

- Lyons, Leslie. Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) Archived November 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Feline Genome Project

- Norsworthy, Gary D.; Crystal, Mitchell A.; Fooshee Grace, Sharon; Tilley, Larry P. (2007). The Feline Patient. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7817-6268-7.

- Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Advice for Breeders Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine The Winn Feline Foundation

- Rah, H; Maggs, D. J.; Blankenship, T. N.; Narfstrom, K; Lyons, L. A. (2005). "Early-onset, autosomal recessive, progressive retinal atrophy in Persian cats". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 46 (5): 1742–7. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-1019. PMID 15851577.

- Rah, H.; Maggs, D.; Lyons, L. (2006). "Lack of genetic association among coat colors, progressive retinal atrophy and polycystic kidney disease in Persian cats". J Feline Med Surg. 8 (5): 357–60. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2006.04.002. PMC 10822235. PMID 16777456. S2CID 32147182.

- Strain, George M. Cat Breeds With Congenital Deafness

- Keller, G.G.; Reed, A.L.; Lattimer, J.C.; Corley, E.A. (1999). "Hip Dysplasia: A Feline Population Study". Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 40 (5). Wiley: 460–464. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.1999.tb00375.x. ISSN 1058-8183. PMID 10528838.

- Gould, Alex; Thomas, Alison (2004). Breed Predispositions to Diseases in Dogs and Cats. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0748-8.

- "Dermatophytosis". Genetic welfare problems of companion animals. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- "Portosystemic Shunt". Genetic welfare problems of companion animals. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- Griseofulvin (Fulvicin) VeterinaryPartner.com

- Rhodes, Karen Helton; Werner, Alexander H. (January 25, 2011). Blackwell's Five-Minute Veterinary Consult Clinical Companion. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-8138-1596-1.

- Copping, Jasper (March 14, 2009). "Inbred pedigree cats suffering from life-threatening diseases and deformities". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- Steiger, Andreas (2005). "Chapter 10: Breeding and Welfare". In Rochlitz, Irene (ed.). The Welfare of Cats. 3. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-6143-1.

- "What You Need to Know Before Bringing Home a Persian Cat". m.petmd.com. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Fawcett, Kirstin (October 26, 2015). "Sotheby's Is Auctioning Off What Might Be the World's Largest Cat Painting". Mental Floss. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- "Carl Kahler My Wife's Lovers Auction". Architectural Digest. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Saul, Emily (November 3, 2015). "World's largest cat painting sells for $826K". New York Post. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- "thepawmag". Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- "10 Fancy Facts About Persian Cats". November 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- "U.S. Postal Stamps Will Feature Cats In 2016". IHeartCats.com. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- "The Top 10 Smartest Cat Breeds In The World". Pets or Animals. January 4, 2020. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2020.