| Pink-headed duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted specimen at National Museum of Scotland | |

| Conservation status | |

Critically Endangered (IUCN 3.1) | |

| CITES Appendix I (CITES) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Rhodonessa Reichenbach, 1853 |

| Species: | R. caryophyllacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham, 1790) | |

| |

| Distribution of records of this species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anas caryophyllacea | |

The pink-headed duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea) is a large diving duck that was once found in parts of the Gangetic plains of India, Nepal, parts of Maharashtra, Bangladesh and in the riverine swamps of Myanmar but has been feared extinct since the 1950s. Numerous searches have failed to provide any proof of continued existence. It has been suggested that it may exist in the inaccessible swamp regions of northern Myanmar and some sight reports from that region have led to its status being declared as "Critically Endangered" rather than extinct. The genus placement has been disputed and while some have suggested that it is close to the red-crested pochard (Netta rufina), others have placed it in a separate genus of its own. It is unique in the pink colouration of the head combined with a dark body. A prominent wing patch and the long slender neck are features shared with the common Indian spot-billed duck. The eggs have also been held as particularly peculiar in being nearly spherical.

Description

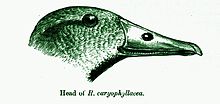

The male pink-headed duck is unmistakable when a good view is had. Both sexes are 41–43 cm and long-billed with long necks and peaked heads. The male has a pink bill, head and neck while the female has a pale pinkish head and neck with a paler bill. The black of the body extends as a narrow strip on the front of the neck. Wings have a leading white edge. In flight it would not contrast as much as the syntopic white-winged duck. Wing does not have the dark trailing edge of the red-crested pochard. Confusion with male red-crested pochards stems mainly from observations of swimming birds, as the latter species also has a conspicuous red head (although the color is actually very different from the pink-headed duck). Indian spot-billed ducks, on the other hand, can look similar to female pink-headed ducks when in flight and seen from a distance, and if seen from behind, they could be mistaken for males too. The upper side of the wing is distinguishing, with dark green secondaries (speculum) and prominent white tertiaries in the spot-billed duck and a pinkish-beige speculum, much lighter than its surroundings, in the pink-headed duck. If the upper part of the wings cannot be reliably seen, they are all but indistinguishable except to expert observers in good visibility conditions. Young birds had a nearly whitish head without a trace of pink and a mellow two note call wugh-ah has been attributed to the species.

Its breeding habitat is lowland marshes and pools in tall-grass jungle. The nest is built amongst grass. The eggs, six or seven in a clutch, are very spherical and creamy white. The eggs measure 1.71 to 1.82 inches long and 1.61 to 1.7 inches wide. They were believed to have been non-migratory and found singly or in pairs and very rarely in small groups. Pink-headed ducks are believed to have eaten water plants and molluscs. Like Netta species, they typically up-ended or dabbled for food and did not dive like a pochard.

Distribution

Allan Octavian Hume and Stuart Baker noted that the stronghold of the species was north of the Ganges and west of the Brahmaputra, mainly in Maldah, Purnea, Madhubani and Purulia districts of present-day Bihar. It was said to be commoner in Singhbum. Hume collected a specimen in Manipur which he noted was very rare, hiding among dense reeds in Loktak Lake. Edward Blyth claimed that it was found in the Rakhine state of Burma. Brian Houghton Hodgson obtained specimens from Nepal. A few records were also noted from Delhi, Sindh and Punjab. The populations (possibly) undertook local seasonal movements, resulting in scattered historic records as far as Punjab, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Thus, resulting in rare sightings of the species in Maharashtra. Birds were also reported from the Oudh region some from very close to Lucknow. Specimens were shot at Najafgarh lake in the Delhi district. Jerdon obtained specimens of the bird from further south although he did not personally observe any in the wild until he visited Bengal.

Taxonomy and systematics

The pink-headed duck was described by John Latham in 1790 under the genus Anas. In describing the species, it is possible that he made of use of a painting in the collection of Lady Impey, wife of Sir Elijah Impey who was Chief Justice of court in Calcutta from 1774 to 1783. Mary Impey maintained a menagerie in Calcutta and commissioned Indian artists such as Bhawani Das from Patna to illustrate animals in the collection. The Impeys moved to England, and after the death of her husband, she sold these paintings at auction in 1810. Some of them were acquired by the 13th Earl of Derby.

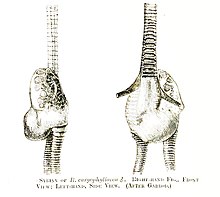

The genus Rhodonessa was originally created for this species alone. Jean Delacour and Ernst Mayr, in their 1945 revision of the family Anatidae considered it a somewhat abnormal member of the Anatini (or river-ducks) group because the hind toe is slightly lobed, display behaviour and the tendency to feed at the surface. The birds were observed in European aviaries and although they never bred, the males displayed often and this involved puffing the neck feathers, lowering the neck to rest on the back and then stretching up the neck while producing a wheezy whistle like a mallard. A study of its tracheal anatomy by Alfred Henry Garrod in 1875 suggested that it had a "slight fusiform dilatation" in the anterior syringeal region. The "bulba ossea" at the lower part of the male syrinx is peculiar in being swollen. The colour pattern has also been considered unique, lacking any of the metallic colours on the secondaries that are characteristic of the Anatini. The other unique feature being the somewhat large and nearly spherical shape of the eggs. All of these features supporting the retention of the species in a separate genus. Such mid-tracheal swellings were found only in Mergini and Aythyini and is extremely rare in the genus Anas. This tracheal bulla is rounded in Anas but angular with fenestrae in Netta and Aythya. Johnsgard considered Marmaronetta and Rhodonessa as intermediate in form. Based on the available morphological and behavioural evidence, especially the structure of the humerus and the structure of tracheal rings, Sidney Dillon Ripley suggested that it was undoubtedly in the Aythyini.

A study found that Rhodonessa was closely allied to the red-crested pochard (Netta rufina) suggesting that the two species be placed in the same genus. Rhodonessa was described prior to Netta which would then make Rhodonessa rufina the name of choice, however these changes have not been widely accepted. The pink colour is derived from a carotenoid pigment which is unusual among ducks and known only from a few other species such as the pink-eared duck which are not closely related.

Status

This duck formerly occurred in eastern India, Nepal, Bangladesh and northern Myanmar, but is now probably extinct. It was always rare, and the last confirmed sighting, by C. M. Inglis, was from Bhagownie, Darbhangha District, in June 1935, with reports from India persisting until the early 1960s. These include reports from Monghyr and from near Shimla. Sidney Dillon Ripley considered it likely extinct in 1950.

In 1988, Rory Nugent, an American birder, and Shankar Barua of Delhi, reported spotting the elusive bird on the banks of the Brahmaputra. The pair started their quest for the bird at Saikhoa ghat on the north-eastern end of the river on the Indian side of the border. After 29 days of sailing, Nugent said that he saw the pink-headed duck amidst a flock of other waterbirds. However, Nugent and Barua's claimed sighting has not been widely accepted. Reports of pink-headed ducks after the 1960s have been received from the largely unexplored Mali Hka and Chindwin Myit drainages in Northern Myanmar. While the area is not very well surveyed by scientists, searches have been inconclusive and confusion with the red-crested pochard and the Indian spot-billed duck has been a common source of supposed pink-headed duck sightings. A report on a survey in the Hu Kaung valley in November 2003 concluded that there is sufficient reason to believe that pink-headed ducks may still exist in Northern Myanmar's Kachin State, but a thorough survey of the Nat Kaung river between Kamaing and Shadusup in October 2005 failed to find this species; a number of interesting ducks were observed, but they turned out to be Indian spot-billed ducks or white-winged ducks. Suggestions have been made that it may be nocturnal.

In 2017, an expedition to find the species by Global Wildlife Conservation also failed, with evidence indicating that the biodiversity in the general area around Indawgyi Lake and its surrounding areas was heavily declining due to habitat degradation. Anecdotes from residents in the area, however, indicate that the bird may have lived in the area far more recently than the last confirmed report from 1910, possibly as recently as 2010. One resident stated that a pink-headed duck was sighted in 1998, associating with a flock of gadwall and pintail. Another, more dubious report stated that shortly after a failed expedition in the area by Birdlife International ended, a local hunter caught a live male and a female or juvenile pink-headed duck, and contacted Myanmar's Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association to sell it to them for a fee. The offer was declined, and the hunter killed both ducks. Another hunter recalled that when the habitat was in good condition, pink-headed ducks were regulars in the area, possibly up to 2014. They were apparently most common during February, and he also could mimic their possible calls, though it is unknown whether these calls were truly by pink-headed ducks. The hunter also said that there were large, impassable ponds in the wetland's center that may still hold pink-headed ducks, but these could only be accessed with a drone, which are banned in the region.

The reason for its disappearance was probably habitat destruction. It is not known why it was always considered rare, but the rarity is believed to be genuine (and not an artefact of insufficient fieldwork) as its erstwhile habitat was frequently scoured by hunters in Colonial times. The pink-headed duck was much sought after by hunters and later as an ornamental bird, mainly because of its unusual plumage. Like most diving ducks, it was not considered good eating, which should facilitate the survival of any remnant birds. The last specimen was obtained in 1935 in Darbhanga by C. M. Inglis. Some birds were also kept in the aviaries of Jean Théodore Delacour in Clères (France) and Alfred Ezra at Foxwarren Park (England) where the last known birds lived in captivity. The only known photographs of the species were taken here and include one of a pair taken around 1925 by David Seth-Smith.

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Rhodonessa caryophyllacea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22680344A125558688. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22680344A125558688.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.{{cite iucn}}: |volume= / |doi= mismatch, |date= / |doi= mismatch (help)

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Latham, John (1790). Index ornithologicus, sive Systema Ornithologiae; complectens avium divisionem in classes, ordines, genera, species, ipsarumque varietates: adjectis synonymis, locis, descriptionibus, &c. London: Leigh & Sotheby.

- King, F. Wayne (1988). "Extant Unless Proven Extinct: The International Legal Precedent". Conservation Biology. 2 (4): 395–397. Bibcode:1988ConBi...2..395K. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.1988.tb00205.x.

- Rasmussen, P. C.; Anderton, J. C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Vol. 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Editions. p. 78.

- Phillips, John C. (1922). A natural history of the ducks. Vol. 1. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 90–93.

- Ali, S.; Ripley, S. D. (1978). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 175–177. ISBN 0-19-562063-1.

- Barnes, H. E. (1891). "Nesting in western India". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 6 (3): 285–317.

- Oates, Eugene W. (1902). Catalogue of the collections of birds' eggs in the British Museum (Natural History). Vol. II. London: British Museum. p. 143.

- ^ Baker, E. C. S. (1897). "Indian ducks and their allies. Part II". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 11 (2): 171–198.

- ^ Humphrey, P. S.; Ripley, S. D. (1962). "The affinities of the Pink-headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea)". Postilla. 61: 1–21.

- Inglis, C. M. (1904). "The birds of the Madhubani subdivision of the Darbhanga district, Tirhut, with notes on species noted elsewhere in the district. Part VIII". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 16 (1): 70–75.

- Hume, Allan (1888). "The Birds of Manipur, Assam, Sylhet and Cachar". Stray Feathers. 11: 1–353.

- Marshall, A. H. (1918). "Occurrence of the Pinkheaded Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea in the Punjab". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 25 (3): 502–503.

- Ara, Jamal (1960). "In search of the Pinkheaded Duck [Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham)]". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 57 (2): 415–417.

- Irby, L. H. (1861). "Notes on birds observed in Oudh and Kumaon". Ibis. 3 (2): 217–251. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1861.tb07456.x.

- Reid, Geo (1879). Hume, Allan (ed.). "[Letter to on specimen of Pink-headed Duck in Lucknow Museum]". Stray Feathers. 8: 418.

- Hume, A. O.; Marshall, C. H. T. (1881). Game birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. Vol. 3. Self-published. pp. 173–180.

- Simson, F. B. (1884). "Notes on the Pink-headed Duck (Anas caryophyllacea)". Ibis. 5 (2): 271–275. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.1884.tb01165.x.

- Jerdon, T. C. (1864). The game birds and wild fowl of India. Calcutta: Military Orphan Press. pp. 176–177.

- Stephens, J. F. (1824). General Zoology. Volume 12 part 2. Aves. pp. 207–208.

- ^ Ezra, Alfred (1926). "The Pink-headed Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea". The Avicultural Magazine. 4 (12): 24.

- Fisher, C. T., ed. (2002). A Passion for Natural History: The Life and Legacy of the 13th Earl of Derby. National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside. ISBN 1-902700-14-7.

- Fisher, C.; Kear, J. (2002). "The taxonomic importance of two early paintings of the pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham 1790)". Bull. Brit. Orn. Club. 122 (4): 244–248.

- Delacour, Jean; Mayr, Ernst (1945). "The Family Anatidae". Wilson Bull. 57: 3–55.

- Garrod, Alfred Henry (1875). "On the form of the lower larynx in certain species of ducks". Proc. Zool. Soc. London: 151–156.

- Blanford WT (1898). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume 4. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 425–426.

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (161). "The Taxonomy of the Anatidae: A behavioural analysis". Ibis. 103: 71–85. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1961.tb02421.x. S2CID 35642972.

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (1965). "Tribe Aythyini (Pochards)". Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0207-7.

- Woolfenden, G. E. (1959). "Postcranial osteology of the waterfowl". Bull. Fla. State Mus. 6 (1): 183–187.

- Livezey, B. C. (1998). "A phylogenetic analysis of modern pochards (Anatidae: Aythini)" (PDF). The Auk. 113 (1): 74–93. doi:10.2307/4088937. JSTOR 4088937.

- Collar, N. J.; Andreev, A. V.; Chan, S.; Crosby, M. J.; Subramanya, S.; Tobias, J. A., eds. (2001). "Pink-headed Duck". Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book (PDF). BirdLife International. pp. 489–501. ISBN 0-946888-44-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- Thomas, Daniel B.; James, Helen F. (2016). "Nondestructive Raman spectroscopy confirms carotenoid-pigmented plumage in the Pink-headed Duck" (PDF). The Auk. 133 (2): 147–154. doi:10.1642/AUK-15-152.1. ISSN 0004-8038. S2CID 54210463.

- Jardine, E. R. (1909). "Occurrence of the Pink-headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea) in Burma". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 19 (1): 264.

- Whistler, H. (1916). "The Pink-headed Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea, Lath. in the Punjab". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 24 (3): 599.

- Hume, A. O. (1879). "Gleanings from the Calcutta market". Stray Feathers. 7 (6): 479–498.

- Singh, Laliteshwar Prasad (1966). "The Pinkheaded Duck [Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham)] again". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 63 (2): 440.

- Mehta, K. L. (1960). "A Pinkheaded Duck at last?". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 57 (2): 417.

- Ripley, S. Dillon (1950). "Two birds about which more information is needed". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 49 (1): 119–120.

- Nugent, Rory (1991). The search for the Pink-headed Duck. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. ISBN 0-395-50552-6.

- ^ Nguyen, Thi Ngoc Ha, ed. (2003). "Pink-headed Duck survey in the Hukaung Valley, Myanmar" (PDF). Babbler. 8: 6–7.

- Hanh, Dang Nguyen Hong, ed. (2005). "Latest search fails to locate Pink-headed Duck" (PDF). Babbler. 16: 21–22.

- Tordoff, Andrew W.; Appleton, T.; Eames, J. C.; Eberhardt, K.; Hla, Htin; Khin Ma Ma Thwin; Sawo Myow Zaw; Moses, Saw; Sein Myo Aung (2008). "The historical and current status of Pink-headed Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea in Myanmar". Bird Conservation International. 18: 38–52. doi:10.1017/S0959270908000063.

- Species, Lost (2017-12-08). "Pink-headed Duck Expedition Report: Myanmar 2017". Lost Species. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Species, Lost (2017-12-08). "Search for the Pink-headed Duck: The Interviews". Lost Species. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- Inglis, C.M. (1940). "Records of some rare, or uncommon, geese and ducks and other water birds and waders in North Bihar". Journal of the Bengal Natural History Society. 15 (2): 56–60.

- Hoage, R. J.; Deiss, William A. (1996). New Worlds, New Animals. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-8018-5373-7.

- Swainson, W. (1838). The cabinet cyclopaedia. Animals in menageries. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green & Longmans, and John Taylor. pp. 277–278.

- Anonymous (1875). Revised list of the vertebrated animals now or lately living in the gardens of the Zoological Society. Zoological Society of London. p. 29.

Other sources

- Ali, S. (1960). "The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham)". Wildfowl Trust 1lth Annual Report. pp. 54–58.

- Bucknill, JA (1924). "The disappearance of the Pink-headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea Lath.)". Ibis. 66 (1): 146–151. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1924.tb08120.x.

- van der Ven, Joost (2007). Roze is een kleur – Zoektochten naar een eend in Myanmar 1999–2006. Utrecht: IJzer.

External links

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Rhodonessa caryophyllacea |

|