In physics, Planck's law (also Planck radiation law) describes the spectral density of electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body in thermal equilibrium at a given temperature T, when there is no net flow of matter or energy between the body and its environment.

At the end of the 19th century, physicists were unable to explain why the observed spectrum of black-body radiation, which by then had been accurately measured, diverged significantly at higher frequencies from that predicted by existing theories. In 1900, German physicist Max Planck heuristically derived a formula for the observed spectrum by assuming that a hypothetical electrically charged oscillator in a cavity that contained black-body radiation could only change its energy in a minimal increment, E, that was proportional to the frequency of its associated electromagnetic wave. While Planck originally regarded the hypothesis of dividing energy into increments as a mathematical artifice, introduced merely to get the correct answer, other physicists including Albert Einstein built on his work, and Planck's insight is now recognized to be of fundamental importance to quantum theory.

The law

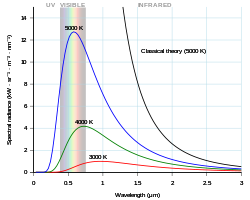

Every physical body spontaneously and continuously emits electromagnetic radiation and the spectral radiance of a body, Bν, describes the spectral emissive power per unit area, per unit solid angle and per unit frequency for particular radiation frequencies. The relationship given by Planck's radiation law, given below, shows that with increasing temperature, the total radiated energy of a body increases and the peak of the emitted spectrum shifts to shorter wavelengths. According to Planck's distribution law, the spectral energy density (energy per unit volume per unit frequency) at given temperature is given by:alternatively, the law can be expressed for the spectral radiance of a body for frequency ν at absolute temperature T given as:where kB is the Boltzmann constant, h is the Planck constant, and c is the speed of light in the medium, whether material or vacuum. The cgs units of spectral radiance Bν are erg·s·sr·cm·Hz. The terms B and u are related to each other by a factor of 4π/c since B is independent of direction and radiation travels at speed c. The spectral radiance can also be expressed per unit wavelength λ instead of per unit frequency. In addition, the law may be expressed in other terms, such as the number of photons emitted at a certain wavelength, or the energy density in a volume of radiation.

In the limit of low frequencies (i.e. long wavelengths), Planck's law tends to the Rayleigh–Jeans law, while in the limit of high frequencies (i.e. small wavelengths) it tends to the Wien approximation.

Max Planck developed the law in 1900 with only empirically determined constants, and later showed that, expressed as an energy distribution, it is the unique stable distribution for radiation in thermodynamic equilibrium. As an energy distribution, it is one of a family of thermal equilibrium distributions which include the Bose–Einstein distribution, the Fermi–Dirac distribution and the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

Black-body radiation

Main article: Black-body radiation

A black-body is an idealised object which absorbs and emits all radiation frequencies. Near thermodynamic equilibrium, the emitted radiation is closely described by Planck's law and because of its dependence on temperature, Planck radiation is said to be thermal radiation, such that the higher the temperature of a body the more radiation it emits at every wavelength.

Planck radiation has a maximum intensity at a wavelength that depends on the temperature of the body. For example, at room temperature (~300 K), a body emits thermal radiation that is mostly infrared and invisible. At higher temperatures the amount of infrared radiation increases and can be felt as heat, and more visible radiation is emitted so the body glows visibly red. At higher temperatures, the body is bright yellow or blue-white and emits significant amounts of short wavelength radiation, including ultraviolet and even x-rays. The surface of the Sun (~6000 K) emits large amounts of both infrared and ultraviolet radiation; its emission is peaked in the visible spectrum. This shift due to temperature is called Wien's displacement law.

Planck radiation is the greatest amount of radiation that any body at thermal equilibrium can emit from its surface, whatever its chemical composition or surface structure. The passage of radiation across an interface between media can be characterized by the emissivity of the interface (the ratio of the actual radiance to the theoretical Planck radiance), usually denoted by the symbol ε. It is in general dependent on chemical composition and physical structure, on temperature, on the wavelength, on the angle of passage, and on the polarization. The emissivity of a natural interface is always between ε = 0 and 1.

A body that interfaces with another medium which both has ε = 1 and absorbs all the radiation incident upon it is said to be a black body. The surface of a black body can be modelled by a small hole in the wall of a large enclosure which is maintained at a uniform temperature with opaque walls that, at every wavelength, are not perfectly reflective. At equilibrium, the radiation inside this enclosure is described by Planck's law, as is the radiation leaving the small hole.

Just as the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution is the unique maximum entropy energy distribution for a gas of material particles at thermal equilibrium, so is Planck's distribution for a gas of photons. By contrast to a material gas where the masses and number of particles play a role, the spectral radiance, pressure and energy density of a photon gas at thermal equilibrium are entirely determined by the temperature.

If the photon gas is not Planckian, the second law of thermodynamics guarantees that interactions (between photons and other particles or even, at sufficiently high temperatures, between the photons themselves) will cause the photon energy distribution to change and approach the Planck distribution. In such an approach to thermodynamic equilibrium, photons are created or annihilated in the right numbers and with the right energies to fill the cavity with a Planck distribution until they reach the equilibrium temperature. It is as if the gas is a mixture of sub-gases, one for every band of wavelengths, and each sub-gas eventually attains the common temperature.

The quantity Bν(ν, T) is the spectral radiance as a function of temperature and frequency. It has units of W·m·sr·Hz in the SI system. An infinitesimal amount of power Bν(ν, T) cos θ dA dΩ dν is radiated in the direction described by the angle θ from the surface normal from infinitesimal surface area dA into infinitesimal solid angle dΩ in an infinitesimal frequency band of width dν centered on frequency ν. The total power radiated into any solid angle is the integral of Bν(ν, T) over those three quantities, and is given by the Stefan–Boltzmann law. The spectral radiance of Planckian radiation from a black body has the same value for every direction and angle of polarization, and so the black body is said to be a Lambertian radiator.

Different forms

Planck's law can be encountered in several forms depending on the conventions and preferences of different scientific fields. The various forms of the law for spectral radiance are summarized in the table below. Forms on the left are most often encountered in experimental fields, while those on the right are most often encountered in theoretical fields.

| with h | with ħ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| variable | distribution | variable | distribution |

| Frequency ν |

Angular frequency ω |

||

| Wavelength λ |

Angular wavelength y |

||

| Wavenumber ν̃ |

Angular wavenumber k |

||

| Fractional bandwidth ln x |

|||

In the fractional bandwidth formulation, , and the integration is with respect to .

Planck's law can also be written in terms of the spectral energy density (u) by multiplying B by 4π/c:

| with h | with ħ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| variable | distribution | variable | distribution |

| Frequency ν |

Angular frequency ω |

||

| Wavelength λ |

Angular wavelength y |

||

| Wavenumber ν̃ |

Angular wavenumber k |

||

| Fractional bandwidth ln x |

|||

These distributions represent the spectral radiance of blackbodies—the power emitted from the emitting surface, per unit projected area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle, per spectral unit (frequency, wavelength, wavenumber or their angular equivalents, or fractional frequency or wavelength). Since the radiance is isotropic (i.e. independent of direction), the power emitted at an angle to the normal is proportional to the projected area, and therefore to the cosine of that angle as per Lambert's cosine law, and is unpolarized.

Correspondence between spectral variable forms

Different spectral variables require different corresponding forms of expression of the law. In general, one may not convert between the various forms of Planck's law simply by substituting one variable for another, because this would not take into account that the different forms have different units. Wavelength and frequency units are reciprocal.

Corresponding forms of expression are related because they express one and the same physical fact: for a particular physical spectral increment, a corresponding particular physical energy increment is radiated.

This is so whether it is expressed in terms of an increment of frequency, dν, or, correspondingly, of wavelength, dλ, or of fractional bandwidth, dν/ν or dλ/λ. Introduction of a minus sign can indicate that an increment of frequency corresponds with decrement of wavelength.

In order to convert the corresponding forms so that they express the same quantity in the same units we multiply by the spectral increment. Then, for a particular spectral increment, the particular physical energy increment may be written which leads to

Also, ν(λ) = c/λ, so that dν/dλ = − c/λ. Substitution gives the correspondence between the frequency and wavelength forms, with their different dimensions and units. Consequently,

Evidently, the location of the peak of the spectral distribution for Planck's law depends on the choice of spectral variable. Nevertheless, in a manner of speaking, this formula means that the shape of the spectral distribution is independent of temperature, according to Wien's displacement law, as detailed below in § Properties §§ Percentiles.

The fractional bandwidth form is related to the other forms by

- .

First and second radiation constants

In the above variants of Planck's law, the wavelength and wavenumber variants use the terms 2hc and hc/kB which comprise physical constants only. Consequently, these terms can be considered as physical constants themselves, and are therefore referred to as the first radiation constant c1L and the second radiation constant c2 with

c1L = 2hcand

c2 = hc/kB.Using the radiation constants, the wavelength variant of Planck's law can be simplified to and the wavenumber variant can be simplified correspondingly.

L is used here instead of B because it is the SI symbol for spectral radiance. The L in c1L refers to that. This reference is necessary because Planck's law can be reformulated to give spectral radiant exitance M(λ, T) rather than spectral radiance L(λ, T), in which case c1 replaces c1L, with

c1 = 2πhc,so that Planck's law for spectral radiant exitance can be written as

As measuring techniques have improved, the General Conference on Weights and Measures has revised its estimate of c2; see Planckian locus § International Temperature Scale for details.

Physics

Planck's law describes the unique and characteristic spectral distribution for electromagnetic radiation in thermodynamic equilibrium, when there is no net flow of matter or energy. Its physics is most easily understood by considering the radiation in a cavity with rigid opaque walls. Motion of the walls can affect the radiation. If the walls are not opaque, then the thermodynamic equilibrium is not isolated. It is of interest to explain how the thermodynamic equilibrium is attained. There are two main cases: (a) when the approach to thermodynamic equilibrium is in the presence of matter, when the walls of the cavity are imperfectly reflective for every wavelength or when the walls are perfectly reflective while the cavity contains a small black body (this was the main case considered by Planck); or (b) when the approach to equilibrium is in the absence of matter, when the walls are perfectly reflective for all wavelengths and the cavity contains no matter. For matter not enclosed in such a cavity, thermal radiation can be approximately explained by appropriate use of Planck's law.

Classical physics led, via the equipartition theorem, to the ultraviolet catastrophe, a prediction that the total blackbody radiation intensity was infinite. If supplemented by the classically unjustifiable assumption that for some reason the radiation is finite, classical thermodynamics provides an account of some aspects of the Planck distribution, such as the Stefan–Boltzmann law, and the Wien displacement law. For the case of the presence of matter, quantum mechanics provides a good account, as found below in the section headed Einstein coefficients. This was the case considered by Einstein, and is nowadays used for quantum optics. For the case of the absence of matter, quantum field theory is necessary, because non-relativistic quantum mechanics with fixed particle numbers does not provide a sufficient account.

Photons

Quantum theoretical explanation of Planck's law views the radiation as a gas of massless, uncharged, bosonic particles, namely photons, in thermodynamic equilibrium. Photons are viewed as the carriers of the electromagnetic interaction between electrically charged elementary particles. Photon numbers are not conserved. Photons are created or annihilated in the right numbers and with the right energies to fill the cavity with the Planck distribution. For a photon gas in thermodynamic equilibrium, the internal energy density is entirely determined by the temperature; moreover, the pressure is entirely determined by the internal energy density. This is unlike the case of thermodynamic equilibrium for material gases, for which the internal energy is determined not only by the temperature, but also, independently, by the respective numbers of the different molecules, and independently again, by the specific characteristics of the different molecules. For different material gases at given temperature, the pressure and internal energy density can vary independently, because different molecules can carry independently different excitation energies.

Planck's law arises as a limit of the Bose–Einstein distribution, the energy distribution describing non-interactive bosons in thermodynamic equilibrium. In the case of massless bosons such as photons and gluons, the chemical potential is zero and the Bose–Einstein distribution reduces to the Planck distribution. There is another fundamental equilibrium energy distribution: the Fermi–Dirac distribution, which describes fermions, such as electrons, in thermal equilibrium. The two distributions differ because multiple bosons can occupy the same quantum state, while multiple fermions cannot. At low densities, the number of available quantum states per particle is large, and this difference becomes irrelevant. In the low density limit, the Bose–Einstein and the Fermi–Dirac distribution each reduce to the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation

Main article: Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiationKirchhoff's law of thermal radiation is a succinct and brief account of a complicated physical situation. The following is an introductory sketch of that situation, and is very far from being a rigorous physical argument. The purpose here is only to summarize the main physical factors in the situation, and the main conclusions.

Spectral dependence of thermal radiation

There is a difference between conductive heat transfer and radiative heat transfer. Radiative heat transfer can be filtered to pass only a definite band of radiative frequencies.

It is generally known that the hotter a body becomes, the more heat it radiates at every frequency.

In a cavity in an opaque body with rigid walls that are not perfectly reflective at any frequency, in thermodynamic equilibrium, there is only one temperature, and it must be shared in common by the radiation of every frequency.

One may imagine two such cavities, each in its own isolated radiative and thermodynamic equilibrium. One may imagine an optical device that allows radiative heat transfer between the two cavities, filtered to pass only a definite band of radiative frequencies. If the values of the spectral radiances of the radiations in the cavities differ in that frequency band, heat may be expected to pass from the hotter to the colder. One might propose to use such a filtered transfer of heat in such a band to drive a heat engine. If the two bodies are at the same temperature, the second law of thermodynamics does not allow the heat engine to work. It may be inferred that for a temperature common to the two bodies, the values of the spectral radiances in the pass-band must also be common. This must hold for every frequency band. This became clear to Balfour Stewart and later to Kirchhoff. Balfour Stewart found experimentally that of all surfaces, one of lamp-black emitted the greatest amount of thermal radiation for every quality of radiation, judged by various filters.

Thinking theoretically, Kirchhoff went a little further and pointed out that this implied that the spectral radiance, as a function of radiative frequency, of any such cavity in thermodynamic equilibrium must be a unique universal function of temperature. He postulated an ideal black body that interfaced with its surrounds in just such a way as to absorb all the radiation that falls on it. By the Helmholtz reciprocity principle, radiation from the interior of such a body would pass unimpeded directly to its surroundings without reflection at the interface. In thermodynamic equilibrium, the thermal radiation emitted from such a body would have that unique universal spectral radiance as a function of temperature. This insight is the root of Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation.

Relation between absorptivity and emissivity

One may imagine a small homogeneous spherical material body labeled X at a temperature TX, lying in a radiation field within a large cavity with walls of material labeled Y at a temperature TY. The body X emits its own thermal radiation. At a particular frequency ν, the radiation emitted from a particular cross-section through the centre of X in one sense in a direction normal to that cross-section may be denoted Iν,X(TX), characteristically for the material of X. At that frequency ν, the radiative power from the walls into that cross-section in the opposite sense in that direction may be denoted Iν,Y(TY), for the wall temperature TY. For the material of X, defining the absorptivity αν,X,Y(TX, TY) as the fraction of that incident radiation absorbed by X, that incident energy is absorbed at a rate αν,X,Y(TX, TY) Iν,Y(TY).

The rate q(ν,TX,TY) of accumulation of energy in one sense into the cross-section of the body can then be expressed

Kirchhoff's seminal insight, mentioned just above, was that, at thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T, there exists a unique universal radiative distribution, nowadays denoted Bν(T), that is independent of the chemical characteristics of the materials X and Y, that leads to a very valuable understanding of the radiative exchange equilibrium of any body at all, as follows.

When there is thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T, the cavity radiation from the walls has that unique universal value, so that Iν,Y(TY) = Bν(T). Further, one may define the emissivity εν,X(TX) of the material of the body X just so that at thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature TX = T, one has Iν,X(TX) = Iν,X(T) = εν,X(T) Bν(T).

When thermal equilibrium prevails at temperature T = TX = TY, the rate of accumulation of energy vanishes so that q(ν,TX,TY) = 0. It follows that in thermodynamic equilibrium, when T = TX = TY,

Kirchhoff pointed out that it follows that in thermodynamic equilibrium, when T = TX = TY,

Introducing the special notation αν,X(T) for the absorptivity of material X at thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T (justified by a discovery of Einstein, as indicated below), one further has the equality at thermodynamic equilibrium.

The equality of absorptivity and emissivity here demonstrated is specific for thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T and is in general not to be expected to hold when conditions of thermodynamic equilibrium do not hold. The emissivity and absorptivity are each separately properties of the molecules of the material but they depend differently upon the distributions of states of molecular excitation on the occasion, because of a phenomenon known as "stimulated emission", that was discovered by Einstein. On occasions when the material is in thermodynamic equilibrium or in a state known as local thermodynamic equilibrium, the emissivity and absorptivity become equal. Very strong incident radiation or other factors can disrupt thermodynamic equilibrium or local thermodynamic equilibrium. Local thermodynamic equilibrium in a gas means that molecular collisions far outweigh light emission and absorption in determining the distributions of states of molecular excitation.

Kirchhoff pointed out that he did not know the precise character of Bν(T), but he thought it important that it should be found out. Four decades after Kirchhoff's insight of the general principles of its existence and character, Planck's contribution was to determine the precise mathematical expression of that equilibrium distribution Bν(T).

Black body

Main article: Black bodyIn physics, one considers an ideal black body, here labeled B, defined as one that completely absorbs all of the electromagnetic radiation falling upon it at every frequency ν (hence the term "black"). According to Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation, this entails that, for every frequency ν, at thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T, one has αν,B(T) = εν,B(T) = 1, so that the thermal radiation from a black body is always equal to the full amount specified by Planck's law. No physical body can emit thermal radiation that exceeds that of a black body, since if it were in equilibrium with a radiation field, it would be emitting more energy than was incident upon it.

Though perfectly black materials do not exist, in practice a black surface can be accurately approximated. As to its material interior, a body of condensed matter, liquid, solid, or plasma, with a definite interface with its surroundings, is completely black to radiation if it is completely opaque. That means that it absorbs all of the radiation that penetrates the interface of the body with its surroundings, and enters the body. This is not too difficult to achieve in practice. On the other hand, a perfectly black interface is not found in nature. A perfectly black interface reflects no radiation, but transmits all that falls on it, from either side. The best practical way to make an effectively black interface is to simulate an 'interface' by a small hole in the wall of a large cavity in a completely opaque rigid body of material that does not reflect perfectly at any frequency, with its walls at a controlled temperature. Beyond these requirements, the component material of the walls is unrestricted. Radiation entering the hole has almost no possibility of escaping the cavity without being absorbed by multiple impacts with its walls.

Lambert's cosine law

Main article: Lambert's cosine lawAs explained by Planck, a radiating body has an interior consisting of matter, and an interface with its contiguous neighbouring material medium, which is usually the medium from within which the radiation from the surface of the body is observed. The interface is not composed of physical matter but is a theoretical conception, a mathematical two-dimensional surface, a joint property of the two contiguous media, strictly speaking belonging to neither separately. Such an interface can neither absorb nor emit, because it is not composed of physical matter; but it is the site of reflection and transmission of radiation, because it is a surface of discontinuity of optical properties. The reflection and transmission of radiation at the interface obey the Stokes–Helmholtz reciprocity principle.

At any point in the interior of a black body located inside a cavity in thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T the radiation is homogeneous, isotropic and unpolarized. A black body absorbs all and reflects none of the electromagnetic radiation incident upon it. According to the Helmholtz reciprocity principle, radiation from the interior of a black body is not reflected at its surface, but is fully transmitted to its exterior. Because of the isotropy of the radiation in the body's interior, the spectral radiance of radiation transmitted from its interior to its exterior through its surface is independent of direction.

This is expressed by saying that radiation from the surface of a black body in thermodynamic equilibrium obeys Lambert's cosine law. This means that the spectral flux dΦ(dA, θ, dΩ, dν) from a given infinitesimal element of area dA of the actual emitting surface of the black body, detected from a given direction that makes an angle θ with the normal to the actual emitting surface at dA, into an element of solid angle of detection dΩ centred on the direction indicated by θ, in an element of frequency bandwidth dν, can be represented as where L(dA, dν) denotes the flux, per unit area per unit frequency per unit solid angle, that area dA would show if it were measured in its normal direction θ = 0.

The factor cos θ is present because the area to which the spectral radiance refers directly is the projection, of the actual emitting surface area, onto a plane perpendicular to the direction indicated by θ . This is the reason for the name cosine law.

Taking into account the independence of direction of the spectral radiance of radiation from the surface of a black body in thermodynamic equilibrium, one has L(dA, dν) = Bν(T) and so

Thus Lambert's cosine law expresses the independence of direction of the spectral radiance Bν (T) of the surface of a black body in thermodynamic equilibrium.

Stefan–Boltzmann law

Main article: Stefan–Boltzmann lawThe total power emitted per unit area at the surface of a black body (P) may be found by integrating the black body spectral flux found from Lambert's law over all frequencies, and over the solid angles corresponding to a hemisphere (h) above the surface.

The infinitesimal solid angle can be expressed in spherical polar coordinates: So that: where is known as the Stefan–Boltzmann constant.

Radiative transfer

Main article: Radiative transferThe equation of radiative transfer describes the way in which radiation is affected as it travels through a material medium. For the special case in which the material medium is in thermodynamic equilibrium in the neighborhood of a point in the medium, Planck's law is of special importance.

For simplicity, we can consider the linear steady state, without scattering. The equation of radiative transfer states that for a beam of light going through a small distance ds, energy is conserved: The change in the (spectral) radiance of that beam (Iν) is equal to the amount removed by the material medium plus the amount gained from the material medium. If the radiation field is in equilibrium with the material medium, these two contributions will be equal. The material medium will have a certain emission coefficient and absorption coefficient.

The absorption coefficient α is the fractional change in the intensity of the light beam as it travels the distance ds, and has units of length. It is composed of two parts, the decrease due to absorption and the increase due to stimulated emission. Stimulated emission is emission by the material body which is caused by and is proportional to the incoming radiation. It is included in the absorption term because, like absorption, it is proportional to the intensity of the incoming radiation. Since the amount of absorption will generally vary linearly as the density ρ of the material, we may define a "mass absorption coefficient" κν = α/ρ which is a property of the material itself. The change in intensity of a light beam due to absorption as it traverses a small distance ds will then be

The "mass emission coefficient" jν is equal to the radiance per unit volume of a small volume element divided by its mass (since, as for the mass absorption coefficient, the emission is proportional to the emitting mass) and has units of power⋅solid angle⋅frequency⋅density. Like the mass absorption coefficient, it too is a property of the material itself. The change in a light beam as it traverses a small distance ds will then be

The equation of radiative transfer will then be the sum of these two contributions:

If the radiation field is in equilibrium with the material medium, then the radiation will be homogeneous (independent of position) so that dIν = 0 and: which is another statement of Kirchhoff's law, relating two material properties of the medium, and which yields the radiative transfer equation at a point around which the medium is in thermodynamic equilibrium:

Einstein coefficients

Main article: Atomic spectral lineThe principle of detailed balance states that, at thermodynamic equilibrium, each elementary process is equilibrated by its reverse process.

In 1916, Albert Einstein applied this principle on an atomic level to the case of an atom radiating and absorbing radiation due to transitions between two particular energy levels, giving a deeper insight into the equation of radiative transfer and Kirchhoff's law for this type of radiation. If level 1 is the lower energy level with energy E1, and level 2 is the upper energy level with energy E2, then the frequency ν of the radiation radiated or absorbed will be determined by Bohr's frequency condition:

If n1 and n2 are the number densities of the atom in states 1 and 2 respectively, then the rate of change of these densities in time will be due to three processes:

- Spontaneous emission

- Stimulated emission

- Photo-absorption

where uν is the spectral energy density of the radiation field. The three parameters A21, B21 and B12, known as the Einstein coefficients, are associated with the photon frequency ν produced by the transition between two energy levels (states). As a result, each line in a spectrum has its own set of associated coefficients. When the atoms and the radiation field are in equilibrium, the radiance will be given by Planck's law and, by the principle of detailed balance, the sum of these rates must be zero:

Since the atoms are also in equilibrium, the populations of the two levels are related by the Boltzmann factor: where g1 and g2 are the multiplicities of the respective energy levels. Combining the above two equations with the requirement that they be valid at any temperature yields two relationships between the Einstein coefficients: so that knowledge of one coefficient will yield the other two.

For the case of isotropic absorption and emission, the emission coefficient (jν) and absorption coefficient (κν) defined in the radiative transfer section above, can be expressed in terms of the Einstein coefficients. The relationships between the Einstein coefficients will yield the expression of Kirchhoff's law expressed in the Radiative transfer section above, namely that

These coefficients apply to both atoms and molecules.

Properties

Peaks

Main article: Wien's displacement lawThe distributions Bν, Bω, Bν̃ and Bk peak at a photon energy ofwhere W is the Lambert W function and e is Euler's number.

However, the distribution Bλ peaks at a different energyThe reason for this is that, as mentioned above, one cannot go from (for example) Bν to Bλ simply by substituting ν by λ. In addition, one must also multiply by , which shifts the peak of the distribution to higher energies. These peaks are the mode energy of a photon, when binned using equal-size bins of frequency or wavelength, respectively. Dividing hc (14387.770 μm·K) by these energy expression gives the wavelength of the peak.

The spectral radiance at these peaks is given by:

with andwith

Meanwhile, the average energy of a photon from a blackbody iswhere is the Riemann zeta function.

Approximations

In the limit of low frequencies (i.e. long wavelengths), Planck's law becomes the Rayleigh–Jeans law or

The radiance increases as the square of the frequency, illustrating the ultraviolet catastrophe. In the limit of high frequencies (i.e. small wavelengths) Planck's law tends to the Wien approximation: or

Percentiles

| Percentile | λT (μm·K) | λkBT/hc |

|---|---|---|

| 0.01% | 910 | 0.0632 |

| 0.1% | 1110 | 0.0771 |

| 1% | 1448 | 0.1006 |

| 10% | 2195 | 0.1526 |

| 20% | 2676 | 0.1860 |

| 25.0% | 2898 | 0.2014 |

| 30% | 3119 | 0.2168 |

| 40% | 3582 | 0.2490 |

| 41.8% | 3670 | 0.2551 |

| 50% | 4107 | 0.2855 |

| 60% | 4745 | 0.3298 |

| 64.6% | 5099 | 0.3544 |

| 70% | 5590 | 0.3885 |

| 80% | 6864 | 0.4771 |

| 90% | 9376 | 0.6517 |

| 99% | 22884 | 1.5905 |

| 99.9% | 51613 | 3.5873 |

| 99.99% | 113374 | 7.8799 |

Wien's displacement law in its stronger form states that the shape of Planck's law is independent of temperature. It is therefore possible to list the percentile points of the total radiation as well as the peaks for wavelength and frequency, in a form which gives the wavelength λ when divided by temperature T. The second column of the following table lists the corresponding values of λT, that is, those values of x for which the wavelength λ is x/T micrometers at the radiance percentile point given by the corresponding entry in the first column.

That is, 0.01% of the radiation is at a wavelength below 910/T μm, 20% below 2676/T μm, etc. The wavelength and frequency peaks are in bold and occur at 25.0% and 64.6% respectively. The 41.8% point is the wavelength-frequency-neutral peak (i.e. the peak in power per unit change in logarithm of wavelength or frequency). These are the points at which the respective Planck-law functions 1/λ, ν and ν/λ, respectively, divided by exp(hν/kBT) − 1 attain their maxima. The much smaller gap in ratio of wavelengths between 0.1% and 0.01% (1110 is 22% more than 910) than between 99.9% and 99.99% (113374 is 120% more than 51613) reflects the exponential decay of energy at short wavelengths (left end) and polynomial decay at long.

Which peak to use depends on the application. The conventional choice is the wavelength peak at 25.0% given by Wien's displacement law in its weak form. For some purposes the median or 50% point dividing the total radiation into two-halves may be more suitable. The latter is closer to the frequency peak than to the wavelength peak because the radiance drops exponentially at short wavelengths and only polynomially at long. The neutral peak occurs at a shorter wavelength than the median for the same reason.

| Percentile | Sun λ (μm) | Black body at 5778K | 288 K planet λ (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01% | 0.203 | 0.157 | 3.16 |

| 0.1% | 0.235 | 0.192 | 3.85 |

| 1% | 0.296 | 0.251 | 5.03 |

| 10% | 0.415 | 0.380 | 7.62 |

| 20% | 0.484 | 0.463 | 9.29 |

| 25.0% | 0.520 | 0.502 | 10.1 |

| 30% | 0.556 | .540 | 10.8 |

| 41.8% | 0.650 | 0.635 | 12.7 |

| 50% | 0.727 | 0.711 | 14.3 |

| 60% | 0.844 | 0.821 | 16.5 |

| 64.6% | 0.911 | 0.882 | 17.7 |

| 70% | 1.003 | 0.967 | 19.4 |

| 80% | 1.242 | 1.188 | 23.8 |

| 90% | 1.666 | 1.623 | 32.6 |

| 99% | 3.728 | 3.961 | 79.5 |

| 99.9% | 8.208 | 8.933 | 179 |

| 99.99% | 17.548 | 19.620 | 394 |

Comparison to solar spectrum

Solar radiation can be compared to black-body radiation at about 5778 K (but see graph). The table on the right shows how the radiation of a black body at this temperature is partitioned, and also how sunlight is partitioned for comparison. Also for comparison a planet modeled as a black body is shown, radiating at a nominal 288 K (15 °C) as a representative value of the Earth's highly variable temperature. Its wavelengths are more than twenty times that of the Sun, tabulated in the third column in micrometers (thousands of nanometers).

That is, only 1% of the Sun's radiation is at wavelengths shorter than 296 nm, and only 1% at longer than 3728 nm. Expressed in micrometers this puts 98% of the Sun's radiation in the range from 0.296 to 3.728 μm. The corresponding 98% of energy radiated from a 288 K planet is from 5.03 to 79.5 μm, well above the range of solar radiation (or below if expressed in terms of frequencies ν = c/λ instead of wavelengths λ).

A consequence of this more-than-order-of-magnitude difference in wavelength between solar and planetary radiation is that filters designed to pass one and block the other are easy to construct. For example, windows fabricated of ordinary glass or transparent plastic pass at least 80% of the incoming 5778 K solar radiation, which is below 1.2 μm in wavelength, while blocking over 99% of the outgoing 288 K thermal radiation from 5 μm upwards, wavelengths at which most kinds of glass and plastic of construction-grade thickness are effectively opaque.

The Sun's radiation is that arriving at the top of the atmosphere (TOA). As can be read from the table, radiation below 400 nm, or ultraviolet, is about 8%, while that above 700 nm, or infrared, starts at about the 48% point and so accounts for 52% of the total. Hence only 40% of the TOA insolation is visible to the human eye. The atmosphere shifts these percentages substantially in favor of visible light as it absorbs most of the ultraviolet and significant amounts of infrared.

Derivations

Photon gas

See also: Gas in a box and Photon gasConsider a cube of side L with conducting walls filled with electromagnetic radiation in thermal equilibrium at temperature T. If there is a small hole in one of the walls, the radiation emitted from the hole will be characteristic of a perfect black body. We will first calculate the spectral energy density within the cavity and then determine the spectral radiance of the emitted radiation.

At the walls of the cube, the parallel component of the electric field and the orthogonal component of the magnetic field must vanish. Analogous to the wave function of a particle in a box, one finds that the fields are superpositions of periodic functions. The three wavelengths λ1, λ2, and λ3, in the three directions orthogonal to the walls can be:where the ni are positive integers. For each set of integers ni there are two linearly independent solutions (known as modes). The two modes for each set of these ni correspond to the two polarization states of the photon which has a spin of 1. According to quantum theory, the total energy of a mode is given by:

| 1 |

The number r can be interpreted as the number of photons in the mode. For r = 0 the energy of the mode is not zero. This vacuum energy of the electromagnetic field is responsible for the Casimir effect. In the following we will calculate the internal energy of the box at absolute temperature T.

According to statistical mechanics, the equilibrium probability distribution over the energy levels of a particular mode is given by:where we use the reciprocal temperatureThe denominator Z(β), is the partition function of a single mode. It makes Pr properly normalized, and can be evaluated aswith

| 2 |

being the energy of a single photon. The average energy in a mode can be obtained from the partition function:This formula, apart from the first vacuum energy term, is a special case of the general formula for particles obeying Bose–Einstein statistics. Since there is no restriction on the total number of photons, the chemical potential is zero.

If we measure the energy relative to the ground state, the total energy in the box follows by summing ⟨E⟩ − ε/2 over all allowed single photon states. This can be done exactly in the thermodynamic limit as L approaches infinity. In this limit, ε becomes continuous and we can then integrate ⟨E⟩ − ε/2 over this parameter. To calculate the energy in the box in this way, we need to evaluate how many photon states there are in a given energy range. If we write the total number of single photon states with energies between ε and ε + dε as g(ε) dε, where g(ε) is the density of states (which is evaluated below), then the total energy is given by

| 3 |

To calculate the density of states we rewrite equation (2) as follows:where n is the norm of the vector n = (n1, n2, n3).

For every vector n with integer components larger than or equal to zero, there are two photon states. This means that the number of photon states in a certain region of n-space is twice the volume of that region. An energy range of dε corresponds to shell of thickness dn = 2L/hc dε in n-space. Because the components of n have to be positive, this shell spans an octant of a sphere. The number of photon states g(ε) dε, in an energy range dε, is thus given by:Inserting this in Eq. (3) and dividing by volume V = L gives the total energy densitywhere the frequency-dependent spectral energy density uν(T) is given bySince the radiation is the same in all directions, and propagates at the speed of light, the spectral radiance of radiation exiting the small hole iswhich yields the Planck's lawOther forms of the law can be obtained by change of variables in the total energy integral. The above derivation is based on Brehm & Mullin 1989.

Dipole approximation and Einstein Coefficients

See also: Einstein coefficients § Dipole ApproximationFor the non-degenerate case, A and B coefficients can be calculated using dipole approximation in time dependent perturbation theory in quantum mechanics. Calculation of A also requires second quantization since semi-classical theory cannot explain spontaneous emission which does not go to zero as perturbing field goes to zero. The transition rates hence calculated are (in SI units):

Note that the rate of transition formula depends on dipole moment operator. For higher order approximations, it involves quadrupole moment and other similar terms. The A and B coefficients (which correspond to angular frequency energy distribution) are hence:

where and A and B coefficients satisfy the given ratios for non degenerate case:

- and .

Another useful ratio is that from maxwell distribution which says that the number of particles in an energy level is proportional to the exponent of . Mathematically:

where and are number of occupied energy levels of and respectively, where . Then, using:

Solving for for equilibrium condition , and using the derived ratios, we get Planck's Law:

- .

History

Balfour Stewart

In 1858, Balfour Stewart described his experiments on the thermal radiative emissive and absorptive powers of polished plates of various substances, compared with the powers of lamp-black surfaces, at the same temperature. Stewart chose lamp-black surfaces as his reference because of various previous experimental findings, especially those of Pierre Prevost and of John Leslie. He wrote "Lamp-black, which absorbs all the rays that fall upon it, and therefore possesses the greatest possible absorbing power, will possess also the greatest possible radiating power."

Stewart measured radiated power with a thermo-pile and sensitive galvanometer read with a microscope. He was concerned with selective thermal radiation, which he investigated with plates of substances that radiated and absorbed selectively for different qualities of radiation rather than maximally for all qualities of radiation. He discussed the experiments in terms of rays which could be reflected and refracted, and which obeyed the Helmholtz reciprocity principle (though he did not use an eponym for it). He did not in this paper mention that the qualities of the rays might be described by their wavelengths, nor did he use spectrally resolving apparatus such as prisms or diffraction gratings. His work was quantitative within these constraints. He made his measurements in a room temperature environment, and quickly so as to catch his bodies in a condition near the thermal equilibrium in which they had been prepared by heating to equilibrium with boiling water. His measurements confirmed that substances that emit and absorb selectively respect the principle of selective equality of emission and absorption at thermal equilibrium.

Stewart offered a theoretical proof that this should be the case separately for every selected quality of thermal radiation, but his mathematics was not rigorously valid. According to historian D. M. Siegel: "He was not a practitioner of the more sophisticated techniques of nineteenth-century mathematical physics; he did not even make use of the functional notation in dealing with spectral distributions." He made no mention of thermodynamics in this paper, though he did refer to conservation of vis viva. He proposed that his measurements implied that radiation was both absorbed and emitted by particles of matter throughout depths of the media in which it propagated. He applied the Helmholtz reciprocity principle to account for the material interface processes as distinct from the processes in the interior material. He concluded that his experiments showed that, in the interior of an enclosure in thermal equilibrium, the radiant heat, reflected and emitted combined, leaving any part of the surface, regardless of its substance, was the same as would have left that same portion of the surface if it had been composed of lamp-black. He did not mention the possibility of ideally perfectly reflective walls; in particular he noted that highly polished real physical metals absorb very slightly.

Gustav Kirchhoff

In 1859, not knowing of Stewart's work, Gustav Robert Kirchhoff reported the coincidence of the wavelengths of spectrally resolved lines of absorption and of emission of visible light. Importantly for thermal physics, he also observed that bright lines or dark lines were apparent depending on the temperature difference between emitter and absorber.

Kirchhoff then went on to consider bodies that emit and absorb heat radiation, in an opaque enclosure or cavity, in equilibrium at temperature T.

Here is used a notation different from Kirchhoff's. Here, the emitting power E(T, i) denotes a dimensioned quantity, the total radiation emitted by a body labeled by index i at temperature T. The total absorption ratio a(T, i) of that body is dimensionless, the ratio of absorbed to incident radiation in the cavity at temperature T . (In contrast with Balfour Stewart's, Kirchhoff's definition of his absorption ratio did not refer in particular to a lamp-black surface as the source of the incident radiation.) Thus the ratio E(T, i)/a(T, i) of emitting power to absorption ratio is a dimensioned quantity, with the dimensions of emitting power, because a(T, i) is dimensionless. Also here the wavelength-specific emitting power of the body at temperature T is denoted by E(λ, T, i) and the wavelength-specific absorption ratio by a(λ, T, i) . Again, the ratio E(λ, T, i)/a(λ, T, i) of emitting power to absorption ratio is a dimensioned quantity, with the dimensions of emitting power.

In a second report made in 1859, Kirchhoff announced a new general principle or law for which he offered a theoretical and mathematical proof, though he did not offer quantitative measurements of radiation powers. His theoretical proof was and still is considered by some writers to be invalid. His principle, however, has endured: it was that for heat rays of the same wavelength, in equilibrium at a given temperature, the wavelength-specific ratio of emitting power to absorption ratio has one and the same common value for all bodies that emit and absorb at that wavelength. In symbols, the law stated that the wavelength-specific ratio E(λ, T, i)/a(λ, T, i) has one and the same value for all bodies, that is for all values of index i. In this report there was no mention of black bodies.

In 1860, still not knowing of Stewart's measurements for selected qualities of radiation, Kirchhoff pointed out that it was long established experimentally that for total heat radiation, of unselected quality, emitted and absorbed by a body in equilibrium, the dimensioned total radiation ratio E(T, i)/a(T, i), has one and the same value common to all bodies, that is, for every value of the material index i. Again without measurements of radiative powers or other new experimental data, Kirchhoff then offered a fresh theoretical proof of his new principle of the universality of the value of the wavelength-specific ratio E(λ, T, i)/a(λ, T, i) at thermal equilibrium. His fresh theoretical proof was and still is considered by some writers to be invalid.

But more importantly, it relied on a new theoretical postulate of "perfectly black bodies", which is the reason why one speaks of Kirchhoff's law. Such black bodies showed complete absorption in their infinitely thin most superficial surface. They correspond to Balfour Stewart's reference bodies, with internal radiation, coated with lamp-black. They were not the more realistic perfectly black bodies later considered by Planck. Planck's black bodies radiated and absorbed only by the material in their interiors; their interfaces with contiguous media were only mathematical surfaces, capable neither of absorption nor emission, but only of reflecting and transmitting with refraction.

Kirchhoff's proof considered an arbitrary non-ideal body labeled i as well as various perfect black bodies labeled BB. It required that the bodies be kept in a cavity in thermal equilibrium at temperature T . His proof intended to show that the ratio E(λ, T, i)/a(λ, T, i) was independent of the nature i of the non-ideal body, however partly transparent or partly reflective it was.

His proof first argued that for wavelength λ and at temperature T, at thermal equilibrium, all perfectly black bodies of the same size and shape have the one and the same common value of emissive power E(λ, T, BB), with the dimensions of power. His proof noted that the dimensionless wavelength-specific absorption ratio a(λ, T, BB) of a perfectly black body is by definition exactly 1. Then for a perfectly black body, the wavelength-specific ratio of emissive power to absorption ratio E(λ, T, BB)/a(λ, T, BB) is again just E(λ, T, BB), with the dimensions of power. Kirchhoff considered, successively, thermal equilibrium with the arbitrary non-ideal body, and with a perfectly black body of the same size and shape, in place in his cavity in equilibrium at temperature T . He argued that the flows of heat radiation must be the same in each case. Thus he argued that at thermal equilibrium the ratio E(λ, T, i)/a(λ, T, i) was equal to E(λ, T, BB), which may now be denoted Bλ (λ, T), a continuous function, dependent only on λ at fixed temperature T, and an increasing function of T at fixed wavelength λ, at low temperatures vanishing for visible but not for longer wavelengths, with positive values for visible wavelengths at higher temperatures, which does not depend on the nature i of the arbitrary non-ideal body. (Geometrical factors, taken into detailed account by Kirchhoff, have been ignored in the foregoing.)

Thus Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation can be stated: For any material at all, radiating and absorbing in thermodynamic equilibrium at any given temperature T, for every wavelength λ, the ratio of emissive power to absorptive ratio has one universal value, which is characteristic of a perfect black body, and is an emissive power which we here represent by Bλ (λ, T). (For our notation Bλ (λ, T), Kirchhoff's original notation was simply e.)

Kirchhoff announced that the determination of the function Bλ (λ, T) was a problem of the highest importance, though he recognized that there would be experimental difficulties to be overcome. He supposed that like other functions that do not depend on the properties of individual bodies, it would be a simple function. That function Bλ (λ, T) has occasionally been called 'Kirchhoff's (emission, universal) function', though its precise mathematical form would not be known for another forty years, till it was discovered by Planck in 1900. The theoretical proof for Kirchhoff's universality principle was worked on and debated by various physicists over the same time, and later. Kirchhoff stated later in 1860 that his theoretical proof was better than Balfour Stewart's, and in some respects it was so. Kirchhoff's 1860 paper did not mention the second law of thermodynamics, and of course did not mention the concept of entropy which had not at that time been established. In a more considered account in a book in 1862, Kirchhoff mentioned the connection of his law with "Carnot's principle", which is a form of the second law.

According to Helge Kragh, "Quantum theory owes its origin to the study of thermal radiation, in particular to the "blackbody" radiation that Robert Kirchhoff had first defined in 1859–1860."

Empirical and theoretical ingredients for the scientific induction of Planck's law

In 1860, Kirchhoff predicted experimental difficulties for the empirical determination of the function that described the dependence of the black-body spectrum as a function only of temperature and wavelength. And so it turned out. It took some forty years of development of improved methods of measurement of electromagnetic radiation to get a reliable result.

In 1865, John Tyndall described radiation from electrically heated filaments and from carbon arcs as visible and invisible. Tyndall spectrally decomposed the radiation by use of a rock salt prism, which passed heat as well as visible rays, and measured the radiation intensity by means of a thermopile.

In 1880, André-Prosper-Paul Crova published a diagram of the three-dimensional appearance of the graph of the strength of thermal radiation as a function of wavelength and temperature. He determined the spectral variable by use of prisms. He analyzed the surface through what he called "isothermal" curves, sections for a single temperature, with a spectral variable on the abscissa and a power variable on the ordinate. He put smooth curves through his experimental data points. They had one peak at a spectral value characteristic for the temperature, and fell either side of it towards the horizontal axis. Such spectral sections are widely shown even today.

In a series of papers from 1881 to 1886, Langley reported measurements of the spectrum of heat radiation, using diffraction gratings and prisms, and the most sensitive detectors that he could make. He reported that there was a peak intensity that increased with temperature, that the shape of the spectrum was not symmetrical about the peak, that there was a strong fall-off of intensity when the wavelength was shorter than an approximate cut-off value for each temperature, that the approximate cut-off wavelength decreased with increasing temperature, and that the wavelength of the peak intensity decreased with temperature, so that the intensity increased strongly with temperature for short wavelengths that were longer than the approximate cut-off for the temperature.

Having read Langley, in 1888, Russian physicist V.A. Michelson published a consideration of the idea that the unknown Kirchhoff radiation function could be explained physically and stated mathematically in terms of "complete irregularity of the vibrations of ... atoms". At this time, Planck was not studying radiation closely, and believed in neither atoms nor statistical physics. Michelson produced a formula for the spectrum for temperature: where Iλ denotes specific radiative intensity at wavelength λ and temperature θ, and where B1 and c are empirical constants.

In 1898, Otto Lummer and Ferdinand Kurlbaum published an account of their cavity radiation source. Their design has been used largely unchanged for radiation measurements to the present day. It was a platinum box, divided by diaphragms, with its interior blackened with iron oxide. It was an important ingredient for the progressively improved measurements that led to the discovery of Planck's law. A version described in 1901 had its interior blackened with a mixture of chromium, nickel, and cobalt oxides.

The importance of the Lummer and Kurlbaum cavity radiation source was that it was an experimentally accessible source of black-body radiation, as distinct from radiation from a simply exposed incandescent solid body, which had been the nearest available experimental approximation to black-body radiation over a suitable range of temperatures. The simply exposed incandescent solid bodies, that had been used before, emitted radiation with departures from the black-body spectrum that made it impossible to find the true black-body spectrum from experiments.

Planck's views before the empirical facts led him to find his eventual law

Planck first turned his attention to the problem of black-body radiation in 1897. Theoretical and empirical progress enabled Lummer and Pringsheim to write in 1899 that available experimental evidence was approximately consistent with the specific intensity law Cλe where C and c denote empirically measurable constants, and where λ and T denote wavelength and temperature respectively. For theoretical reasons, Planck at that time accepted this formulation, which has an effective cut-off of short wavelengths.

Gustav Kirchhoff was Max Planck's teacher and surmised that there was a universal law for blackbody radiation and this was called "Kirchhoff's challenge". Planck, a theorist, believed that Wilhelm Wien had discovered this law and Planck expanded on Wien's work presenting it in 1899 to the meeting of the German Physical Society. Experimentalists Otto Lummer, Ferdinand Kurlbaum, Ernst Pringsheim Sr., and Heinrich Rubens did experiments that appeared to support Wien's law especially at higher frequency short wavelengths which Planck so wholly endorsed at the German Physical Society that it began to be called the Wien-Planck Law. However, by September 1900, the experimentalists had proven beyond a doubt that the Wien-Planck law failed at the longer wavelengths. They would present their data on October 19. Planck was informed by his friend Rubens and quickly created a formula within a few days. In June of that same year, Lord Rayleigh had created a formula that would work for short lower frequency wavelengths based on the widely accepted theory of equipartition. So Planck submitted a formula combining both Rayleigh's Law (or a similar equipartition theory) and Wien's law which would be weighted to one or the other law depending on wavelength to match the experimental data. However, although this equation worked, Planck himself said unless he could explain the formula derived from a "lucky intuition" into one of "true meaning" in physics, it did not have true significance. Planck explained that thereafter followed the hardest work of his life. Planck did not believe in atoms, nor did he think the second law of thermodynamics should be statistical because probability does not provide an absolute answer, and Boltzmann's entropy law rested on the hypothesis of atoms and was statistical. But Planck was unable to find a way to reconcile his Blackbody equation with continuous laws such as Maxwell's wave equations. So in what Planck called "an act of desperation", he turned to Boltzmann's atomic law of entropy as it was the only one that made his equation work. Therefore, he used the Boltzmann constant k and his new constant h to explain the blackbody radiation law which became widely known through his published paper.

Finding the empirical law

Max Planck produced his law on 19 October 1900 as an improvement upon the Wien approximation, published in 1896 by Wilhelm Wien, which fit the experimental data at short wavelengths (high frequencies) but deviated from it at long wavelengths (low frequencies). In June 1900, based on heuristic theoretical considerations, Rayleigh had suggested a formula that he proposed might be checked experimentally. The suggestion was that the Stewart–Kirchhoff universal function might be of the form c1Tλexp(–c2/λT) . This was not the celebrated Rayleigh–Jeans formula 8πkBTλ, which did not emerge until 1905, though it did reduce to the latter for long wavelengths, which are the relevant ones here. According to Klein, one may speculate that it is likely that Planck had seen this suggestion though he did not mention it in his papers of 1900 and 1901. Planck would have been aware of various other proposed formulas which had been offered. On 7 October 1900, Rubens told Planck that in the complementary domain (long wavelength, low frequency), and only there, Rayleigh's 1900 formula fitted the observed data well.

For long wavelengths, Rayleigh's 1900 heuristic formula approximately meant that energy was proportional to temperature, Uλ = const. T. It is known that dS/dUλ = 1/T and this leads to dS/dUλ = const./Uλ and thence to dS/dUλ = −const./Uλ for long wavelengths. But for short wavelengths, the Wien formula leads to 1/T = − const. ln Uλ + const. and thence to dS/dUλ = − const./Uλ for short wavelengths. Planck perhaps patched together these two heuristic formulas, for long and for short wavelengths, to produce a formula

This led Planck to the formula where Planck used the symbols C and c to denote empirical fitting constants.

Planck sent this result to Rubens, who compared it with his and Kurlbaum's observational data and found that it fitted for all wavelengths remarkably well. On 19 October 1900, Rubens and Kurlbaum briefly reported the fit to the data, and Planck added a short presentation to give a theoretical sketch to account for his formula. Within a week, Rubens and Kurlbaum gave a fuller report of their measurements confirming Planck's law. Their technique for spectral resolution of the longer wavelength radiation was called the residual ray method. The rays were repeatedly reflected from polished crystal surfaces, and the rays that made it all the way through the process were 'residual', and were of wavelengths preferentially reflected by crystals of suitably specific materials.

Trying to find a physical explanation of the law

See also: Planck relationOnce Planck had discovered the empirically fitting function, he constructed a physical derivation of this law. His thinking revolved around entropy rather than being directly about temperature. Planck considered a cavity with perfectly reflective walls; inside the cavity, there are finitely many distinct but identically constituted resonant oscillatory bodies of definite magnitude, with several such oscillators at each of finitely many characteristic frequencies. These hypothetical oscillators were for Planck purely imaginary theoretical investigative probes, and he said of them that such oscillators do not need to "really exist somewhere in nature, provided their existence and their properties are consistent with the laws of thermodynamics and electrodynamics.". Planck did not attribute any definite physical significance to his hypothesis of resonant oscillators but rather proposed it as a mathematical device that enabled him to derive a single expression for the black body spectrum that matched the empirical data at all wavelengths. He tentatively mentioned the possible connection of such oscillators with atoms. In a sense, the oscillators corresponded to Planck's speck of carbon; the size of the speck could be small regardless of the size of the cavity, provided the speck effectively transduced energy between radiative wavelength modes.

Partly following a heuristic method of calculation pioneered by Boltzmann for gas molecules, Planck considered the possible ways of distributing electromagnetic energy over the different modes of his hypothetical charged material oscillators. This acceptance of the probabilistic approach, following Boltzmann, for Planck was a radical change from his former position, which till then had deliberately opposed such thinking proposed by Boltzmann. In Planck's words, "I considered the a purely formal assumption, and I did not give it much thought except for this: that I had obtained a positive result under any circumstances and at whatever cost." Heuristically, Boltzmann had distributed the energy in arbitrary merely mathematical quanta ϵ, which he had proceeded to make tend to zero in magnitude, because the finite magnitude ϵ had served only to allow definite counting for the sake of mathematical calculation of probabilities, and had no physical significance. Referring to a new universal constant of nature, h, Planck supposed that, in the several oscillators of each of the finitely many characteristic frequencies, the total energy was distributed to each in an integer multiple of a definite physical unit of energy, ϵ, characteristic of the respective characteristic frequency. His new universal constant of nature, h, is now known as the Planck constant.

Planck explained further that the respective definite unit, ϵ, of energy should be proportional to the respective characteristic oscillation frequency ν of the hypothetical oscillator, and in 1901 he expressed this with the constant of proportionality h:

Planck did not propose that light propagating in free space is quantized. The idea of quantization of the free electromagnetic field was developed later, and eventually incorporated into what we now know as quantum field theory.

In 1906, Planck acknowledged that his imaginary resonators, having linear dynamics, did not provide a physical explanation for energy transduction between frequencies. Present-day physics explains the transduction between frequencies in the presence of atoms by their quantum excitability, following Einstein. Planck believed that in a cavity with perfectly reflecting walls and with no matter present, the electromagnetic field cannot exchange energy between frequency components. This is because of the linearity of Maxwell's equations. Present-day quantum field theory predicts that, in the absence of matter, the electromagnetic field obeys nonlinear equations and in that sense does self-interact. Such interaction in the absence of matter has not yet been directly measured because it would require very high intensities and very sensitive and low-noise detectors, which are still in the process of being constructed. Planck believed that a field with no interactions neither obeys nor violates the classical principle of equipartition of energy, and instead remains exactly as it was when introduced, rather than evolving into a black body field. Thus, the linearity of his mechanical assumptions precluded Planck from having a mechanical explanation of the maximization of the entropy of the thermodynamic equilibrium thermal radiation field. This is why he had to resort to Boltzmann's probabilistic arguments.

Planck's law may be regarded as fulfilling the prediction of Gustav Kirchhoff that his law of thermal radiation was of the highest importance. In his mature presentation of his own law, Planck offered a thorough and detailed theoretical proof for Kirchhoff's law, theoretical proof of which until then had been sometimes debated, partly because it was said to rely on unphysical theoretical objects, such as Kirchhoff's perfectly absorbing infinitely thin black surface.

Subsequent events

It was not until five years after Planck made his heuristic assumption of abstract elements of energy or of action that Albert Einstein conceived of really existing quanta of light in 1905 as a revolutionary explanation of black-body radiation, of photoluminescence, of the photoelectric effect, and of the ionization of gases by ultraviolet light. In 1905, "Einstein believed that Planck's theory could not be made to agree with the idea of light quanta, a mistake he corrected in 1906." Contrary to Planck's beliefs of the time, Einstein proposed a model and formula whereby light was emitted, absorbed, and propagated in free space in energy quanta localized in points of space. As an introduction to his reasoning, Einstein recapitulated Planck's model of hypothetical resonant material electric oscillators as sources and sinks of radiation, but then he offered a new argument, disconnected from that model, but partly based on a thermodynamic argument of Wien, in which Planck's formula ϵ = hν played no role. Einstein gave the energy content of such quanta in the form Rβν/N. Thus Einstein was contradicting the undulatory theory of light held by Planck. In 1910, criticizing a manuscript sent to him by Planck, knowing that Planck was a steady supporter of Einstein's theory of special relativity, Einstein wrote to Planck: "To me it seems absurd to have energy continuously distributed in space without assuming an aether."

According to Thomas Kuhn, it was not till 1908 that Planck more or less accepted part of Einstein's arguments for physical as distinct from abstract mathematical discreteness in thermal radiation physics. Still in 1908, considering Einstein's proposal of quantal propagation, Planck opined that such a revolutionary step was perhaps unnecessary. Until then, Planck had been consistent in thinking that discreteness of action quanta was to be found neither in his resonant oscillators nor in the propagation of thermal radiation. Kuhn wrote that, in Planck's earlier papers and in his 1906 monograph, there is no "mention of discontinuity, of talk of a restriction on oscillator energy, any formula like U = nhν." Kuhn pointed out that his study of Planck's papers of 1900 and 1901, and of his monograph of 1906, had led him to "heretical" conclusions, contrary to the widespread assumptions of others who saw Planck's writing only from the perspective of later, anachronistic, viewpoints. Kuhn's conclusions, finding a period till 1908, when Planck consistently held his 'first theory', have been accepted by other historians.

In the second edition of his monograph, in 1912, Planck sustained his dissent from Einstein's proposal of light quanta. He proposed in some detail that absorption of light by his virtual material resonators might be continuous, occurring at a constant rate in equilibrium, as distinct from quantal absorption. Only emission was quantal. This has at times been called Planck's "second theory".

It was not till 1919 that Planck in the third edition of his monograph more or less accepted his 'third theory', that both emission and absorption of light were quantal.

The colourful term "ultraviolet catastrophe" was given by Paul Ehrenfest in 1911 to the paradoxical result that the total energy in the cavity tends to infinity when the equipartition theorem of classical statistical mechanics is (mistakenly) applied to black-body radiation. But this had not been part of Planck's thinking, because he had not tried to apply the doctrine of equipartition: when he made his discovery in 1900, he had not noticed any sort of "catastrophe". It was first noted by Lord Rayleigh in 1900, and then in 1901 by Sir James Jeans; and later, in 1905, by Einstein when he wanted to support the idea that light propagates as discrete packets, later called 'photons', and by Rayleigh and by Jeans.

In 1913, Bohr gave another formula with a further different physical meaning to the quantity hν. In contrast to Planck's and Einstein's formulas, Bohr's formula referred explicitly and categorically to energy levels of atoms. Bohr's formula was Wτ2 − Wτ1 = hν where Wτ2 and Wτ1 denote the energy levels of quantum states of an atom, with quantum numbers τ2 and τ1. The symbol ν denotes the frequency of a quantum of radiation that can be emitted or absorbed as the atom passes between those two quantum states. In contrast to Planck's model, the frequency has no immediate relation to frequencies that might describe those quantum states themselves.

Later, in 1924, Satyendra Nath Bose developed the theory of the statistical mechanics of photons, which allowed a theoretical derivation of Planck's law. The actual word 'photon' was invented still later, by G.N. Lewis in 1926, who mistakenly believed that photons were conserved, contrary to Bose–Einstein statistics; nevertheless the word 'photon' was adopted to express the Einstein postulate of the packet nature of light propagation. In an electromagnetic field isolated in a vacuum in a vessel with perfectly reflective walls, such as was considered by Planck, indeed the photons would be conserved according to Einstein's 1905 model, but Lewis was referring to a field of photons considered as a system closed with respect to ponderable matter but open to exchange of electromagnetic energy with a surrounding system of ponderable matter, and he mistakenly imagined that still the photons were conserved, being stored inside atoms.

Ultimately, Planck's law of black-body radiation contributed to Einstein's concept of quanta of light carrying linear momentum, which became the fundamental basis for the development of quantum mechanics.

The above-mentioned linearity of Planck's mechanical assumptions, not allowing for energetic interactions between frequency components, was superseded in 1925 by Heisenberg's original quantum mechanics. In his paper submitted on 29 July 1925, Heisenberg's theory accounted for Bohr's above-mentioned formula of 1913. It admitted non-linear oscillators as models of atomic quantum states, allowing energetic interaction between their own multiple internal discrete Fourier frequency components, on the occasions of emission or absorption of quanta of radiation. The frequency of a quantum of radiation was that of a definite coupling between internal atomic meta-stable oscillatory quantum states. At that time, Heisenberg knew nothing of matrix algebra, but Max Born read the manuscript of Heisenberg's paper and recognized the matrix character of Heisenberg's theory. Then Born and Jordan published an explicitly matrix theory of quantum mechanics, based on, but in form distinctly different from, Heisenberg's original quantum mechanics; it is the Born and Jordan matrix theory that is today called matrix mechanics. Heisenberg's explanation of the Planck oscillators, as non-linear effects apparent as Fourier modes of transient processes of emission or absorption of radiation, showed why Planck's oscillators, viewed as enduring physical objects such as might be envisaged by classical physics, did not give an adequate explanation of the phenomena.

Nowadays, as a statement of the energy of a light quantum, often one finds the formula E = ħω, where ħ = h/2π, and ω = 2πν denotes angular frequency, and less often the equivalent formula E = hν. This statement about a really existing and propagating light quantum, based on Einstein's, has a physical meaning different from that of Planck's above statement ϵ = hν about the abstract energy units to be distributed amongst his hypothetical resonant material oscillators.

An article by Helge Kragh published in Physics World gives an account of this history.

See also

References

- Young, Hugh D.; Freedman, Roger A.; Ford, A. Lewis (2016). University Physics (14th ed.). Perason. pp. 1256–1257. ISBN 9780321973610.

- ^ Planck 1914, p. 42

- Gaofeng Shao, et al. 2019, p. 6.

- Zangwill, Andrew (2013). Modern electrodynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. p. 698. ISBN 978-0-521-89697-9.

- ^ Andrews, David G. (2010). An introduction to atmospheric physics (2nd éd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge university press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-521-87220-1.

- Planck 1914, pp. 6, 168

- ^ Chandrasekhar 1960, p. 8

- Rybicki & Lightman 1979, p. 22

- ^ Stewart 1858

- Hapke 1993, pp. 362–373

- Planck 1914

- Loudon 2000, pp. 3–45

- Caniou 1999, p. 117

- Kramm & Mölders 2009, p. 10

- ^ Sharkov 2003, p. 210

- ^ Marr, Jonathan M.; Wilkin, Francis P. (2012). "A Better Presentation of Planck's Radiation Law". Am. J. Phys. 80 (5): 399. arXiv:1109.3822. Bibcode:2012AmJPh..80..399M. doi:10.1119/1.3696974. S2CID 10556556.

- Fischer 2011

- Goody & Yung 1989, p. 16.

- Mohr, Taylor & Newell 2012, p. 1591

- Loudon 2000

- Mandel & Wolf 1995

- Wilson 1957, p. 182

- Adkins 1983, pp. 147–148

- Landsberg 1978, p. 208

- Siegel & Howell 2002, p. 25

- Planck 1914, pp. 9–11

- Planck 1914, p. 35

- Landsberg 1961, pp. 273–274

- Born & Wolf 1999, pp. 194–199

- Born & Wolf 1999, p. 195

- Rybicki & Lightman 1979, p. 19

- Chandrasekhar 1960, p. 7

- Chandrasekhar 1960, p. 9

- ^ Einstein 1916

- ^ Bohr 1913

- ^ Jammer 1989, pp. 113, 115

- ^ Kittel & Kroemer 1980, p. 98

- ^ Jeans 1905a, p. 98

- ^ Rayleigh 1905

- ^ Rybicki & Lightman 1979, p. 23

- ^ Wien 1896, p. 667

- Planck 1906, p. 158

- Lowen & Blanch 1940

- Integrated from Christian Gueymard (April 2004). "The sun's total and spectral irradiance for solar energy applications and solar radiation models". Solar Energy. 76 (4): 423–453. Bibcode:2004SoEn...76..423G. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2003.08.039.

- Zettili, Nouredine (2009). Quantum mechanics: concepts and applications (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley. pp. 594–596. ISBN 978-0-470-02679-3.

- Segre, Carlo. "The Einstein coefficients - Fundamentals of Quantum Theory II (PHYS 406)" (PDF). p. 32.

- Zwiebach, Barton. "Quantum Physics III Chapter 4: Time Dependent Perturbation Theory | Quantum Physics III | Physics". MIT OpenCourseWare. pp. 108–110. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Siegel 1976

- Kirchhoff 1860a

- Kirchhoff 1860b

- ^ Schirrmacher 2001

- ^ Kirchhoff 1860c

- Planck 1914, p. 11

- Milne 1930, p. 80

- Rybicki & Lightman 1979, pp. 16–17

- Mihalas & Weibel-Mihalas 1984, p. 328

- Goody & Yung 1989, pp. 27–28

- Paschen, F. (1896), personal letter cited by Hermann 1971, p. 6

- Hermann 1971, p. 7

- Kuhn 1978, pp. 8, 29

- Mehra & Rechenberg 1982, pp. 26, 28, 31, 39

- Kirchhoff 1862, p. 573