A vacuum pump is a type of pump device that draws gas particles from a sealed volume in order to leave behind a partial vacuum. The first vacuum pump was invented in 1650 by Otto von Guericke, and was preceded by the suction pump, which dates to antiquity.

History

Early pumps

The predecessor to the vacuum pump was the suction pump. Dual-action suction pumps were found in the city of Pompeii. Arabic engineer Al-Jazari later described dual-action suction pumps as part of water-raising machines in the 13th century. He also said that a suction pump was used in siphons to discharge Greek fire. The suction pump later appeared in medieval Europe from the 15th century.

By the 17th century, water pump designs had improved to the point that they produced measurable vacuums, but this was not immediately understood. What was known was that suction pumps could not pull water beyond a certain height: 18 Florentine yards according to a measurement taken around 1635, or about 34 feet (10 m). This limit was a concern in irrigation projects, mine drainage, and decorative water fountains planned by the Duke of Tuscany, so the duke commissioned Galileo Galilei to investigate the problem. Galileo suggested, incorrectly, in his Two New Sciences (1638) that the column of a water pump will break of its own weight when the water has been lifted to 34 feet. Other scientists took up the challenge, including Gasparo Berti, who replicated it by building the first water barometer in Rome in 1639. Berti's barometer produced a vacuum above the water column, but he could not explain it. A breakthrough was made by Galileo's student Evangelista Torricelli in 1643. Building upon Galileo's notes, he built the first mercury barometer and wrote a convincing argument that the space at the top was a vacuum. The height of the column was then limited to the maximum weight that atmospheric pressure could support; this is the limiting height of a suction pump.

In 1650, Otto von Guericke invented the first vacuum pump. Four years later, he conducted his famous Magdeburg hemispheres experiment, showing that teams of horses could not separate two hemispheres from which the air had been evacuated. Robert Boyle improved Guericke's design and conducted experiments on the properties of vacuum. Robert Hooke also helped Boyle produce an air pump that helped to produce the vacuum.

By 1709, Francis Hauksbee improved on the design further with his two-cylinder pump, where two pistons worked via a rack-and-pinion design that reportedly "gave a vacuum within about one inch of mercury of perfect." This design remained popular and only slightly changed until well into the nineteenth century.

19th century

Heinrich Geissler invented the mercury displacement pump in 1855 and achieved a record vacuum of about 10 Pa (0.1 Torr). A number of electrical properties become observable at this vacuum level, and this renewed interest in vacuum. This, in turn, led to the development of the vacuum tube. The Sprengel pump was a widely used vacuum producer of this time.

20th century

The early 20th century saw the invention of many types of vacuum pump, including the molecular drag pump, the diffusion pump, and the turbomolecular pump.

Types

Pumps can be broadly categorized according to three techniques: positive displacement, momentum transfer, and entrapment. Positive displacement pumps use a mechanism to repeatedly expand a cavity, allow gases to flow in from the chamber, seal off the cavity, and exhaust it to the atmosphere. Momentum transfer pumps, also called molecular pumps, use high-speed jets of dense fluid or high-speed rotating blades to knock gas molecules out of the chamber. Entrapment pumps capture gases in a solid or adsorbed state; this includes cryopumps, getters, and ion pumps.

Positive displacement pumps are the most effective for low vacuums. Momentum transfer pumps, in conjunction with one or two positive displacement pumps, are the most common configuration used to achieve high vacuums. In this configuration the positive displacement pump serves two purposes. First it obtains a rough vacuum in the vessel being evacuated before the momentum transfer pump can be used to obtain the high vacuum, as momentum transfer pumps cannot start pumping at atmospheric pressures. Second the positive displacement pump backs up the momentum transfer pump by evacuating to low vacuum the accumulation of displaced molecules in the high vacuum pump. Entrapment pumps can be added to reach ultrahigh vacuums, but they require periodic regeneration of the surfaces that trap air molecules or ions. Due to this requirement their available operational time can be unacceptably short in low and high vacuums, thus limiting their use to ultrahigh vacuums. Pumps also differ in details like manufacturing tolerances, sealing material, pressure, flow, admission or no admission of oil vapor, service intervals, reliability, tolerance to dust, tolerance to chemicals, tolerance to liquids and vibration.

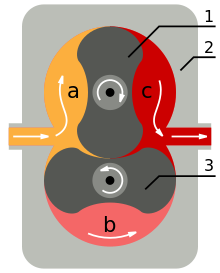

Positive displacement pump

A partial vacuum may be generated by increasing the volume of a container. To continue evacuating a chamber indefinitely without requiring infinite growth, a compartment of the vacuum can be repeatedly closed off, exhausted, and expanded again. This is the principle behind a positive displacement pump, for example the manual water pump. Inside the pump, a mechanism expands a small sealed cavity to reduce its pressure below that of the atmosphere. Because of the pressure differential, some fluid from the chamber (or the well, in our example) is pushed into the pump's small cavity. The pump's cavity is then sealed from the chamber, opened to the atmosphere, and squeezed back to a minute size.

More sophisticated systems are used for most industrial applications, but the basic principle of cyclic volume removal is the same:

- Rotary vane pump, the most common

- Diaphragm pump, zero oil contamination

- Liquid ring high resistance to dust

- Piston pump, fluctuating vacuum

- Scroll pump, highest speed dry pump

- Screw pump (10 Pa)

- Wankel pump

- External vane pump

- Roots blower, also called a booster pump, has highest pumping speeds but low compression ratio

- Multistage Roots pump that combine several stages providing high pumping speed with better compression ratio

- Toepler pump

- Lobe pump

The base pressure of a rubber- and plastic-sealed piston pump system is typically 1 to 50 kPa, while a scroll pump might reach 10 Pa (when new) and a rotary vane oil pump with a clean and empty metallic chamber can easily achieve 0.1 Pa.

A positive displacement vacuum pump moves the same volume of gas with each cycle, so its pumping speed is constant unless it is overcome by backstreaming.

Momentum transfer pump

In a momentum transfer pump (or kinetic pump), gas molecules are accelerated from the vacuum side to the exhaust side (which is usually maintained at a reduced pressure by a positive displacement pump). Momentum transfer pumping is only possible below pressures of about 0.1 kPa. Matter flows differently at different pressures based on the laws of fluid dynamics. At atmospheric pressure and mild vacuums, molecules interact with each other and push on their neighboring molecules in what is known as viscous flow. When the distance between the molecules increases, the molecules interact with the walls of the chamber more often than with the other molecules, and molecular pumping becomes more effective than positive displacement pumping. This regime is generally called high vacuum.

Molecular pumps sweep out a larger area than mechanical pumps, and do so more frequently, making them capable of much higher pumping speeds. They do this at the expense of the seal between the vacuum and their exhaust. Since there is no seal, a small pressure at the exhaust can easily cause backstreaming through the pump; this is called stall. In high vacuum, however, pressure gradients have little effect on fluid flows, and molecular pumps can attain their full potential.

The two main types of molecular pumps are the diffusion pump and the turbomolecular pump. Both types of pumps blow out gas molecules that diffuse into the pump by imparting momentum to the gas molecules. Diffusion pumps blow out gas molecules with jets of an oil or mercury vapor, while turbomolecular pumps use high speed fans to push the gas. Both of these pumps will stall and fail to pump if exhausted directly to atmospheric pressure, so they must be exhausted to a lower grade vacuum created by a mechanical pump, in this case called a backing pump.

As with positive displacement pumps, the base pressure will be reached when leakage, outgassing, and backstreaming equal the pump speed, but now minimizing leakage and outgassing to a level comparable to backstreaming becomes much more difficult.

Entrapment pump

An entrapment pump may be a cryopump, which uses cold temperatures to condense gases to a solid or adsorbed state, a chemical pump, which reacts with gases to produce a solid residue, or an ion pump, which uses strong electrical fields to ionize gases and propel the ions into a solid substrate. A cryomodule uses cryopumping. Other types are the sorption pump, non-evaporative getter pump, and titanium sublimation pump (a type of evaporative getter that can be used repeatedly).

Other types

Regenerative pump

Main article: Pump § Regenerative turbine pumpsRegenerative pumps utilize vortex behavior of the fluid (air). The construction is based on hybrid concept of centrifugal pump and turbopump. Usually it consists of several sets of perpendicular teeth on the rotor circulating air molecules inside stationary hollow grooves like multistage centrifugal pump. They can reach to 1×10 mbar (0.001 Pa)(when combining with Holweck pump) and directly exhaust to atmospheric pressure. Examples of such pumps are Edwards EPX (technical paper ) and Pfeiffer OnTool™ Booster 150. It is sometimes referred as side channel pump. Due to high pumping rate from atmosphere to high vacuum and less contamination since bearing can be installed at exhaust side, this type of pumps are used in load lock in semiconductor manufacturing processes.

This type of pump suffers from high power consumption(~1 kW) compared to turbomolecular pump (<100W) at low pressure since most power is consumed to back atmospheric pressure. This can be reduced by nearly 10 times by backing with a small pump.

More examples

Additional types of pump include the:

- Venturi vacuum pump (aspirator) (10 to 30 kPa)

- Steam ejector (vacuum depends on the number of stages, but can be very low)

Performance measures

Pumping speed refers to the volume flow rate of a pump at its inlet, often measured in volume per unit of time. Momentum transfer and entrapment pumps are more effective on some gases than others, so the pumping rate can be different for each of the gases being pumped, and the average volume flow rate of the pump will vary depending on the chemical composition of the gases remaining in the chamber.

Throughput refers to the pumping speed multiplied by the gas pressure at the inlet, and is measured in units of pressure·volume/unit time. At a constant temperature, throughput is proportional to the number of molecules being pumped per unit time, and therefore to the mass flow rate of the pump. When discussing a leak in the system or backstreaming through the pump, throughput refers to the volume leak rate multiplied by the pressure at the vacuum side of the leak, so the leak throughput can be compared to the pump throughput.

Positive displacement and momentum transfer pumps have a constant volume flow rate (pumping speed), but as the chamber's pressure drops, this volume contains less and less mass. So although the pumping speed remains constant, the throughput and mass flow rate drop exponentially. Meanwhile, the leakage, evaporation, sublimation and backstreaming rates continue to produce a constant throughput into the system.

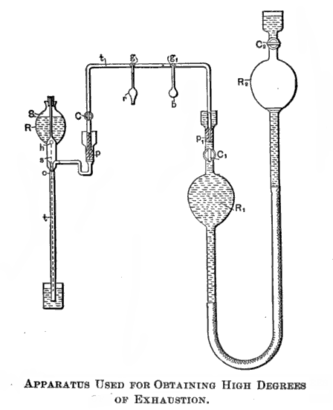

Techniques

Vacuum pumps are combined with chambers and operational procedures into a wide variety of vacuum systems. Sometimes more than one pump will be used (in series or in parallel) in a single application. A partial vacuum, or rough vacuum, can be created using a positive displacement pump that transports a gas load from an inlet port to an outlet (exhaust) port. Because of their mechanical limitations, such pumps can only achieve a low vacuum. To achieve a higher vacuum, other techniques must then be used, typically in series (usually following an initial fast pump down with a positive displacement pump). Some examples might be use of an oil sealed rotary vane pump (the most common positive displacement pump) backing a diffusion pump, or a dry scroll pump backing a turbomolecular pump. There are other combinations depending on the level of vacuum being sought.

Achieving high vacuum is difficult because all of the materials exposed to the vacuum must be carefully evaluated for their outgassing and vapor pressure properties. For example, oils, greases, and rubber or plastic gaskets used as seals for the vacuum chamber must not boil off when exposed to the vacuum, or the gases they produce would prevent the creation of the desired degree of vacuum. Often, all of the surfaces exposed to the vacuum must be baked at high temperature to drive off adsorbed gases.

Outgassing can also be reduced simply by desiccation prior to vacuum pumping. High-vacuum systems generally require metal chambers with metal gasket seals such as Klein flanges or ISO flanges, rather than the rubber gaskets more common in low vacuum chamber seals. The system must be clean and free of organic matter to minimize outgassing. All materials, solid or liquid, have a small vapour pressure, and their outgassing becomes important when the vacuum pressure falls below this vapour pressure. As a result, many materials that work well in low vacuums, such as epoxy, will become a source of outgassing at higher vacuums. With these standard precautions, vacuums of 1 mPa are easily achieved with an assortment of molecular pumps. With careful design and operation, 1 μPa is possible.

Several types of pumps may be used in sequence or in parallel. In a typical pumpdown sequence, a positive displacement pump would be used to remove most of the gas from a chamber, starting from atmosphere (760 Torr, 101 kPa) to 25 Torr (3 kPa). Then a sorption pump would be used to bring the pressure down to 10 Torr (10 mPa). A cryopump or turbomolecular pump would be used to bring the pressure further down to 10 Torr (1 μPa). An additional ion pump can be started below 10 Torr to remove gases which are not adequately handled by a cryopump or turbo pump, such as helium or hydrogen.

Ultra-high vacuum generally requires custom-built equipment, strict operational procedures, and a fair amount of trial-and-error. Ultra-high vacuum systems are usually made of stainless steel with metal-gasketed vacuum flanges. The system is usually baked, preferably under vacuum, to temporarily raise the vapour pressure of all outgassing materials in the system and boil them off. If necessary, this outgassing of the system can also be performed at room temperature, but this takes much more time. Once the bulk of the outgassing materials are boiled off and evacuated, the system may be cooled to lower vapour pressures to minimize residual outgassing during actual operation. Some systems are cooled well below room temperature by liquid nitrogen to shut down residual outgassing and simultaneously cryopump the system.

In ultra-high vacuum systems, some very odd leakage paths and outgassing sources must be considered. The water absorption of aluminium and palladium becomes an unacceptable source of outgassing, and even the absorptivity of hard metals such as stainless steel or titanium must be considered. Some oils and greases will boil off in extreme vacuums. The porosity of the metallic vacuum chamber walls may have to be considered, and the grain direction of the metallic flanges should be parallel to the flange face.

The impact of molecular size must be considered. Smaller molecules can leak in more easily and are more easily absorbed by certain materials, and molecular pumps are less effective at pumping gases with lower molecular weights. A system may be able to evacuate nitrogen (the main component of air) to the desired vacuum, but the chamber could still be full of residual atmospheric hydrogen and helium. Vessels lined with a highly gas-permeable material such as palladium (which is a high-capacity hydrogen sponge) create special outgassing problems.

Applications

Vacuum pumps are used in many industrial and scientific processes, including:

- Vacuum deaerator

- Composite plastic moulding processes;

- Production of most types of electric lamps, vacuum tubes, and CRTs where the device is either left evacuated or re-filled with a specific gas or gas mixture;

- Semiconductor processing, notably ion implantation, dry etch and PVD, ALD, PECVD and CVD deposition and so on in photolithography;

- Electron microscopy;

- Medical processes that require suction;

- Uranium enrichment;

- Medical applications such as radiotherapy, radiosurgery and radiopharmacy;

- Analytical instrumentation to analyse gas, liquid, solid, surface and bio materials;

- Mass spectrometers to create a high vacuum between the ion source and the detector;

- vacuum coating on glass, metal and plastics for decoration, for durability and for energy saving, such as low-emissivity glass, hard coating for engine components (as in Formula One), ophthalmic coating, milking machines and other equipment in dairy sheds;

- Vacuum impregnation of porous products such as wood or electric motor windings;

- Air conditioning service (removing all contaminants from the system before charging with refrigerant);

- Trash compactor;

- Vacuum engineering;

- Sewage systems (see EN1091:1997 standards);

- Freeze drying; and

- Fusion research.

In the field of oil regeneration and re-refining, vacuum pumps create a low vacuum for oil dehydration and a high vacuum for oil purification.

A vacuum may be used to power, or provide assistance to mechanical devices. In hybrid and diesel engine motor vehicles, a pump fitted on the engine (usually on the camshaft) is used to produce a vacuum. In petrol engines, instead, the vacuum is typically obtained as a side-effect of the operation of the engine and the flow restriction created by the throttle plate but may be also supplemented by an electrically operated vacuum pump to boost braking assistance or improve fuel consumption. This vacuum may then be used to power the following motor vehicle components: vacuum servo booster for the hydraulic brakes, motors that move dampers in the ventilation system, throttle driver in the cruise control servomechanism, door locks or trunk releases.

In an aircraft, the vacuum source is often used to power gyroscopes in the various flight instruments. To prevent the complete loss of instrumentation in the event of an electrical failure, the instrument panel is deliberately designed with certain instruments powered by electricity and other instruments powered by the vacuum source.

Depending on the application, some vacuum pumps may either be electrically driven (using electric current) or pneumatically-driven (using air pressure), or powered and actuated by other means.

Hazards

Old vacuum-pump oils that were produced before circa 1980 often contain a mixture of several different dangerous polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are highly toxic, carcinogenic, persistent organic pollutants.

See also

References

- Krafft, Fritz (2013). Otto Von Guerickes Neue (Sogenannte) Magdeburger Versuche über den Leeren Raum (in German). Springer-Verlag. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-662-00949-9.

- "Pompeii: Technology: Working models: IMSS".

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times, Routledge, pp. 143 & 150-2

- Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, May 1991, pp. 64-69 (cf. Donald Routledge Hill, Mechanical Engineering)

- Ahmad Y Hassan. "The Origin of the Suction Pump: Al-Jazari 1206 A.D". Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- "The World's Largest Barometer". Archived from the original on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- Calvert 2000, "Maximum height to which water can be raised by a suction pump".

- Harsch, Viktor (November 2007). "Otto von Gericke (1602–1686) and his pioneering vacuum experiments". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 78 (11): 1075–1077. doi:10.3357/asem.2159.2007. ISSN 0095-6562. PMID 18018443.

- ^ da C. Andrade, E.N. (1953). "The history of the vacuum pump". Vacuum. 9 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1016/0042-207X(59)90555-X.

- Okamura, S., ed. (1994). History of electron tubes. Tokyo: Ohmsha. pp. 7–11. ISBN 90-5199-145-2. OCLC 30995577.

- Dayton, B.B. (1994). "History of the Development of Fusion Pumps". In Redhead, P.A. (ed.). Vacuum science and technology : pioneers of the 20th century : history of vacuum science and technology volume 2. New York, NY: AIP Press for the American Vacuum Society. pp. 107–13. ISBN 1-56396-248-9. OCLC 28587335.

- Redhead, P.A., ed. (1994). Vacuum science and technology : pioneers of the 20th century : history of vacuum science and technology volume 2. New York, NY: AIP Press for the American Vacuum Society. p. 96. ISBN 1-56396-248-9. OCLC 28587335.

- ^ Van Atta, C. M.; M. Hablanian (1991). "Vacuum and Vacuum Technology". In Rita G. Lerner; George L. Trigg (eds.). Encyclopedia of Physics (Second ed.). VCH Publishers Inc. pp. 1330–1333. ISBN 978-3-527-26954-9.

- ^ Van der Heide, Paul (2014). Secondary ion mass spectrometry : an introduction to principles and practices. Hoboken, New Jersey. pp. 253–7. ISBN 978-1-118-91677-3. OCLC 879329842.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Halliday, B.S. (1998). "Chapter 3: Pumps". In Chambers, A. (ed.). Basic vacuum technology. R. K. Fitch, B. S. Halliday (2nd ed.). Bristol: Institute of Physics Pub. ISBN 0-585-25491-5. OCLC 45727687.

- Ekenes, Rolf N. (2009). Southern marine engineering desk reference. United States: Xlibris Corp. pp. 139–40. ISBN 978-1-4415-2022-7. OCLC 757731951.

- Coker, A. Kayode (2007). Ludwig's applied process design for chemical and petrochemical plants. Volume 1. Ernest E. Ludwig (4th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Gulf Professional. p. 562. ISBN 978-0-08-046970-6. OCLC 86068934.

- "EPX on-tool High Vacuum Pumps". Archived from the original on 2013-02-20. Retrieved 2013-01-16.

- "Edwards - Edwards Vacuum" (PDF). 15 September 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2013.

- Pfeiffer Vacuum. "Side Channel Pump, Vacuum pump for High-vacuum - Pfeiffer Vacuum". Pfeiffer Vacuum. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Shirinov, A.; Oberbeck, S. (2011). "High vacuum side channel pump working against atmosphere". Vacuum. 85 (12): 1174–1177. Bibcode:2011Vacuu..85.1174S. doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2010.12.018.

- ^ Hablanian, M. H. (1997). "Chapter 3: Fluid Flow and Pumping Concepts". High-vacuum technology : a practical guide (2nd ed., rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 41–66. ISBN 0-585-13875-3. OCLC 44959885.

- ^ Hablanian, M. H. (1997). "Chapter 4: Vacuum Systems". High-vacuum technology : a practical guide (2nd ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 77–136. ISBN 0-585-13875-3. OCLC 44959885.

- RAO, V V. (2012). "Chapter 5: Vacuum Materials and Components". VACUUM SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. : ALLIED PUBLISHERS PVT LTD. pp. 110–48. ISBN 978-81-7023-763-1. OCLC 1175913128.

- ^ Weston, G. F. (1985). Ultrahigh vacuum practice. London: Butterworths. ISBN 978-1-4831-0332-7. OCLC 567406093.

- Rosato, Dominick V. (2000). Injection Molding Handbook. Donald V. Rosato, Marlene G. Rosato (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Springer US. p. 874. ISBN 978-1-4615-4597-2. OCLC 840285544.

- Lessard, Philip A. (2000). "Dry vacuum pumps for semiconductor processes: Guidelines for primary pump selection". Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A: Vacuum, Surfaces, and Films. 18 (4): 1777–1781. Bibcode:2000JVSTA..18.1777L. doi:10.1116/1.582423. ISSN 0734-2101.

- Yoshimura, Nagamitsu (2020). A review : ultrahigh-vacuum technology for electron microscopes. London. ISBN 978-0-12-819703-5. OCLC 1141514098.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Müller, D. (19 June 2020). "Vacuum Technology in Medical Applications". Vacuum Science World. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Snyder, Ryan (2016-05-03). "A Proliferation Assessment of Third Generation Laser Uranium Enrichment Technology". Science & Global Security. 24 (2): 68–91. Bibcode:2016S&GS...24...68S. doi:10.1080/08929882.2016.1184528. ISSN 0892-9882. S2CID 37413408.

- Ginzton, Edward L.; Nunan, Craig S. (1985). "History of microwave electron linear accelerators for radiotherapy". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 11 (2): 205–216. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(85)90141-5. PMID 3918962.

- Klemm, Denis; Hoffmann, Volker; Edelmann, Christian (2009). "Controlling of material analysers of the GD-OES type with help of pump-down curves". Vacuum. 84 (2): 299–303. Bibcode:2009Vacuu..84..299K. doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2009.06.058.

- Goodwin, D.; Cameron, A.; Ramsden, J. (2005). "Considerations for Primary Vacuum Pumping in Mass Spectrometry Systems". Spectroscopy. 20 (1). et al.

- Mattox, D. M. (2003). The foundations of vacuum coating technology : [a concise look at the discoveries, inventions, and people behind vacuum coating, past and present]. Norwich, N.Y.: Noyes Publications/William Andrew Pub. ISBN 978-0-8155-1925-6. OCLC 310215197.

- Rozanov, L.N. (2002-04-04). Vacuum Technique (0 ed.). CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9781482288155. ISBN 978-1-4822-8815-5.

- Nomura, Takahiro; Okinaka, Noriyuki; Akiyama, Tomohiro (2009). "Impregnation of porous material with phase change material for thermal energy storage". Materials Chemistry and Physics. 115 (2–3): 846–850. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2009.02.045.

- Lattieff, Farkad A.; Atiya, Mohammed A.; Al-Hemiri, Adel A. (2019). "Test of solar adsorption air-conditioning powered by evacuated tube collectors under the climatic conditions of Iraq". Renewable Energy. 142: 20–29. Bibcode:2019REne..142...20L. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.03.014. S2CID 116823643.

- Johnson, Jeff; Marten, Adam; Tellez, Guillerno (2012-07-15). "Design of a High Efficiency, High Output Plastic Melt Waste Compactor". 42nd International Conference on Environmental Systems. International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES). San Diego, California: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2012-3544. ISBN 978-1-60086-934-1.

- Berman, A. (1992). Vacuum Engineering Calculations, Formulas, and Solved Exercises. Oxford: Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-323-14041-6. OCLC 829460307.

- Butler, David (2018). "Chapter 14: Pumped Systems". Urban drainage. Chris Digman, Christos Makropoulos, John W. Davies (4th ed.). Boca Raton, FL. pp. 293–314. ISBN 978-1-4987-5059-2. OCLC 1004770084.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Haseley, Peter (2018). Freeze-drying. Georg-Wilhelm Oetjen (3rd ed.). Weinheim, Germany. ISBN 978-3-527-80894-6. OCLC 1015682292.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nicholas, Nathan; Shaffer, Bryce (February 24, 2020). "All-Metal Scroll Vacuum Pump for Tritium Processing Systems". Fusion Science and Technology. 76 (3): 366–372. Bibcode:2020FuST...76..366N. doi:10.1080/15361055.2020.1712988. S2CID 214329842. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Speight, James; Exall, Douglas (2014). Refining Used Lubricating Oils. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 9781466551503.

- "UP28 Universal Electric Vacuum Pump". Hella. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 14 Jun 2013.

- "Chapter 5. Flight Instruments". Instrument Flying Handbook (PDF) (FAA-H-8083-15B ed.). Federal Aviation Administration Flight Standards Service. 2012. p. 17.

- "Vacuum Pumps". Vacuum Knowledge. J. Schmalz GmbH. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- "Vacuum Generators". Vacuum Knowledge. J. Schmalz GmbH. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- "How a Vacuum Pump Works". Arizona Pneumatic. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Bott, D. "The Ins and Outs of Vacuum Generators". Dr. Vacuum. Dan Bott Consulting LLC. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Martin G Broadhurst (October 1972). "Use and replaceability of polychlorinated biphenyls". Environmental Health Perspectives. 2: 81–102. doi:10.2307/3428101. JSTOR 3428101. PMC 1474898. PMID 4628855.

- C J McDonald & R E Tourangeau (1986). PCBs: Question and Answer Guide Concerning Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Government of Canada: Environment Canada Department. ISBN 978-0-662-14595-0. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

Bibliography

- Calvert, J. B. (11 May 2000). "Hydrostatics". Pressure. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018.