| Do not resuscitate | |

|---|---|

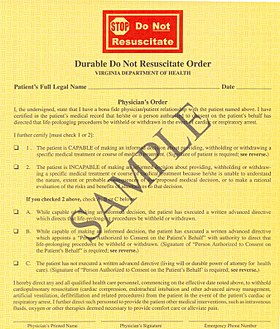

DNR form used in Virginia DNR form used in Virginia | |

| Other names | Do not attempt resuscitation, allow natural death, no code, do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation, do not attempt resuscitation, no CPR, not for resuscitation, not to be resuscitated |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

A do-not-resuscitate order (DNR), also known as Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR), Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR), no code or allow natural death, is a medical order, written or oral depending on the jurisdiction, indicating that a person should not receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if that person's heart stops beating. Sometimes these decisions and the relevant documents also encompass decisions around other critical or life-prolonging medical interventions. The legal status and processes surrounding DNR orders vary in different polities. Most commonly, the order is placed by a physician based on a combination of medical judgement and patient involvement.

Basis for choice

Interviews with 26 DNR patients and 16 full code patients in Toronto, Canada in 2006–2009 suggest that the decision to choose do-not-resuscitate status was based on personal factors including health and lifestyle; relational factors (to family or to society as a whole); and philosophical factors. Audio recordings of 19 discussions about DNR status between doctors and patients in two US hospitals (San Francisco, California and Durham, North Carolina) in 2008–2009 found that patients "mentioned risks, benefits, and outcomes of CPR," and doctors "explored preferences for short- versus long-term use of life-sustaining therapy." A Canadian article suggests that it is inappropriate to offer CPR when the clinician knows the patient has a terminal illness and that CPR will be futile.

Outcomes of CPR

Main article: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation § Survival differences, based on prior illness, age or location

When medical institutions explain DNR, they describe survival from CPR, in order to address patients' concerns about outcomes. After CPR in hospitals in 2017, 7,000 patients survived to leave the hospital alive, out of 26,000 CPR attempts, or 26%. After CPR outside hospitals in 2018, 8,000 patients survived to leave the hospital alive, out of 80,000 CPR attempts, or 10%. Success was 21% in a public setting, where someone was more likely to see the person collapse and give help than in a home. Success was 35% when bystanders used an Automated external defibrillator (AED), outside health facilities and nursing homes.

In information on DNR, medical institutions compare survival for patients with multiple chronic illnesses; patients with heart, lung or kidney disease; liver disease; widespread cancer or infection; and residents of nursing homes. Research shows that CPR survival is the same as the average CPR survival rate, or nearly so, for patients with multiple chronic illnesses, or diabetes, heart or lung diseases. Survival is about half as good as the average rate, for patients with kidney or liver disease, or widespread cancer or infection.

For people who live in nursing homes, survival after CPR is about half to three quarters of the average rate. In health facilities and nursing homes where AEDs are available and used, survival rates are twice as high as the average survival found in nursing homes overall. Few nursing homes have AEDs.

Research on 26,000 patients found similarities in the health situations of patients with and without DNRs. For each of 10 levels of illness, from healthiest to sickest, 7% to 36% of patients had DNR orders; the rest had full code.

Risks

Main article: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation § ConsequencesAs noted above, patients considering DNR mention the risks of CPR. Physical injuries, such as broken bones, affect 13% of CPR patients, and an unknown additional number have broken cartilage which can sound like breaking bones.

Mental problems affect some patients, both before and after CPR. After CPR, up to 1 more person, among each 100 survivors, is in a coma than before CPR (and most people come out of comas). Five to 10 more people, of each 100 survivors, need more help with daily life than they did before CPR. Five to 21 more people, of each 100 survivors, decline mentally, but stay independent.

Organ donation

Organ donation is possible after CPR, but not usually after a death with a DNR. If CPR does not revive the patient, and continues until an operating room is available, then kidneys and liver can be considered for donation. US Guidelines endorse organ donation, "Patients who do not have ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation) after resuscitation efforts and who would otherwise have termination of efforts may be considered candidates for kidney or liver donation in settings where programs exist." European guidelines encourage donation, "After stopping CPR, the possibility of ongoing support of the circulation and transport to a dedicated centre in perspective of organ donation should be considered." CPR revives 64% of patients in hospitals and 43% outside (ROSC), which gives families a chance to say goodbye, and all organs can be considered for donation, "We recommend that all patients who are resuscitated from cardiac arrest but who subsequently progress to death or brain death be evaluated for organ donation."

1,000 organs per year in the US are transplanted from patients who had CPR. Donations can be taken from 40% of patients who have ROSC and later become brain dead, and an average of 3 organs are taken from each patient who donates organs. DNR does not usually allow organ donation.

Less care for DNR patients

Reductions in other care are not supposed to result from a DNAPR decision being in place. Some patients choose DNR because they prefer less care: Half of Oregon patients with DNR orders who filled out a POLST (known as a Physician Orders and Scope of Treatment, or POST, in Tennessee) wanted only comfort care, and 7% wanted full care. The rest wanted various limits on care, so blanket assumptions are not reliable. There are many doctors "misinterpreting DNR preferences and thus not providing other appropriate therapeutic interventions."

Patients with DNR are less likely to get medically appropriate care for a wide range of issues such as blood transfusions, cardiac catheterizations, cardiac bypass, operations for surgical complication, blood cultures, central line placement, antibiotics and diagnostic tests. "Providers intentionally apply DNR orders broadly because they either assume that patients with DNR orders would also prefer to abstain from other life-sustaining treatments or believe that other treatments would not be medically beneficial." 60% of surgeons do not offer operations with over 1% mortality to patients with DNRs. The failure to offer appropriate care to patients with DNR led to the development of emergency care and treatment plans (ECTPs), such as the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT), which aim to record recommendations concerning DNR alongside recommendations for other treatments in an emergency situation. ECTPs have prompted doctors to contextualize CPR within a broader consideration of treatment options, however ECTPs are most frequently completed for patients at risk of sudden deterioration and the focus tends to be on DNR.

Patients with DNR therefore die sooner, even from causes unrelated to CPR. A study grouped 26,300 very sick hospital patients in 2006–2010 from the sickest to the healthiest, using a detailed scale from 0 to 44. They compared survival for patients at the same level, with and without DNR orders. In the healthiest group, 69% of those without DNR survived to leave the hospital, while only 7% of equally healthy patients with DNR survived. In the next-healthiest group, 53% of those without DNR survived, and 6% of those with DNR. Among the sickest patients, 6% of those without DNR survived, and none with DNR.

Two Dartmouth College doctors note that "In the 1990s ... 'resuscitation' increasingly began to appear in the medical literature to describe strategies to treat people with reversible conditions, such as IV fluids for shock from bleeding or infection... the meaning of DNR became ever more confusing to health-care providers." Other researchers confirm this pattern, using "resuscitative efforts" to cover a range of care, from treatment of allergic reaction to surgery for a broken hip. Hospital doctors do not agree which treatments to withhold from DNR patients, and document decisions in the chart only half the time. A survey with several scenarios found doctors "agreed or strongly agreed to initiate fewer interventions when a DNR order was present.

After successful CPR, hospitals often discuss putting the patient on DNR, to avoid another resuscitation. Guidelines generally call for a 72-hour wait to see what the prognosis is, but within 12 hours, US hospitals put up to 58% of survivors on DNR, and at the median hospital, 23% received DNR orders at this early stage, much earlier than the guideline. The hospitals putting fewest patients on DNR had more successful survival rates, which the researchers suggest shows their better care in general. When CPR happened outside the hospital, hospitals put up to 80% of survivors on DNR within 24 hours, with an average of 32.5%. The patients who received DNR orders had less treatment, and almost all died in the hospital. The researchers say families need to expect death if they agree to DNR in the hospital.

Controlled organ donation after circulatory death

In 2017, Critical Care Medicine (Ethics) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Committees on Transplant Anesthesia issued a statement regarding organ donation after circulatory death (DCD). The purpose of the statement is to provide an educational tool for institutions choosing to use DCD. In 2015, nearly 9% of organ transplantations in the United States resulted from DCD, indicating it is a widely-held practice. According to the President's Commission on Death Determination, there are two sets of criteria used to define circulatory death: irreversible absence of circulation and respiration, and irreversible absence of whole brain function. Only one criterion needs to be met for the determination of death before organ donation and both have legal standing, according to the 1980 Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA); a determination of death must be according to accepted medical standards. All states within the United States adhere to the original or modified UDDA. The dead donor role states that a patient should not be killed for or by the donation of their organs and that organs can only be procured from dead people (lungs, kidneys, and lobes of a liver may be donated by living donors in certain highly regulated situations).

The definition of irreversibility centers around an obligatory period of observation to determine that respiration and circulation have ceased and will not resume spontaneously. Clinical examination alone may be sufficient to determine irreversibility, but the urgent time constraints of CDC may require more definitive proof of cessation with confirmatory tests, such as intra-arterial monitoring or Doppler studies. In accordance with the Institute of Medicine, the obligatory period for DCD is longer than 2 minutes but no more than 5 minutes of absent circulatory function before pronouncing the patient dead, which is supported by a lack of literature indicating that spontaneous resuscitation occurs after two minutes of arrest and that ischemic damage to perfusable organs occurs within 5 minutes.

Most patients considered for DCD will have been in the intensive care unit (ICU) and are dependent on ventilatory and circulatory support. Potential DCD donors are still completing the dying process but have not yet been declared dead, so quality end-of-life care should remain the absolute top priority and must not be compromised by the DCD process. The decision to allow death to occur by withdrawing life-sustaining therapies needs to have been made in accordance to the wishes of the patient and/or their legal agent; this must happen prior to any discussions about DCD, which should ideally occur between the patient's primary care giver and the patient's agent after rapport has been established.

Patient values

The philosophical factors and preferences mentioned by patients and doctors are treated in the medical literature as strong guidelines for care, including DNR or CPR. "Complex medical aspects of a patient with a critical illness must be integrated with considerations of the patient's values and preferences" and "the preeminent place of patient values in determining the benefit or burden imposed by medical interventions." Patients' most common goals include talking, touch, prayer, helping others, addressing fears, and laughing. Being mentally aware was as important to patients as avoiding pain, and doctors underestimated its importance and overestimated the importance of pain. Dying at home was less important to most patients. Three quarters of patients prefer longer survival over better health.

Advance directive, living will, POLST, medical jewellery, tattoos

Advance directives and living wills are documents written by individuals themselves, so as to state their wishes for care, if they are no longer able to speak for themselves. In contrast, it is a physician or hospital staff member who writes a DNR "physician's order," based upon the wishes previously expressed by the individual in their advance directive or living will. Similarly, at a time when the individual is unable to express their wishes, but has previously used an advance directive to appoint an agent, then a physician can write such a DNR "physician's order" at the request of that individual's agent. These various situations are clearly enumerated in the "sample" DNR order presented on this page.

It should be stressed that, in the United States, an advance directive or living will is not sufficient to ensure a patient is treated under the DNR protocol, even if it is their wish, as neither an advance directive nor a living will legally binds doctors. They can be legally binding in appointing a medical representative, but not in treatment decisions.

Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) documents are the usual place where a DNR is recorded outside hospitals. A disability rights group criticizes the process, saying doctors are trained to offer very limited scenarios with no alternative treatments, and steer patients toward DNR. They also criticize that DNR orders are absolute, without variations for context. The Mayo Clinic found in 2013 that "Most patients with DNR/DNI (do not intubate) orders want CPR and/or intubation in hypothetical clinical scenarios," so the patients had not had enough explanation of the DNR/DNI or did not understand the explanation.

In the UK, emergency care and treatment plans (e.g. ReSPECT) are clinical recommendations written by healthcare professionals after discussion with patients or their relatives about their priorities of care. Research has found that the involvement of patients or their family in forming ECTP recommendations is variable. In some situations (where there are limited treatment options available, or where the patient is likely to deteriorate quickly) healthcare professionals will not explore the patient's preferences, but will instead ensure that patients or their relatives understand what treatment will or will not be offered.

Medical jewellery

Medical bracelets, medallions, and wallet cards from approved providers allow for identification of DNR patients in home or non-hospital settings. In the US each state has its own DNR policies, procedures, and accompanying paperwork for emergency medical service personnel to comply with such forms of DNR.

DNR tattoos

There is a growing trend of using DNR tattoos, commonly placed on the chest, to replace other forms of DNR, but these often cause confusion and ethical dilemmas among healthcare providers. Laws vary from place to place regarding what constitutes a valid DNR and currently do not include tattoos. End of life (EOL) care preferences are dynamic and depend on factors such as health status, age, prognosis, healthcare access, and medical advancements. DNR orders can be rescinded while tattoos are far more difficult to remove. At least one person decided to get a DNR tattoo based on a dare while under the influence of alcohol.

Ethics and violations

DNR orders in certain situations have been subject to ethical debate. In many institutions it is customary for a patient going to surgery to have their DNR automatically rescinded. Though the rationale for this may be valid, as outcomes from CPR in the operating room are substantially better than general survival outcomes after CPR, the impact on patient autonomy has been debated. It is suggested that facilities engage patients or their decision makers in a 'reconsideration of DNR orders' instead of automatically making a forced decision.

When a patient or family and doctors do not agree on a DNR status, it is common to ask the hospital ethics committee for help, but authors have pointed out that many members have little or no ethics training, some have little medical training, and they do have conflicts of interest by having the same employer and budget as the doctors.

In the United States there is accumulating evidence of racial differences in rates of DNR adoption. A 2014 study of end stage cancer patients found that non-Latino white patients were significantly more likely to have a DNR order (45%) than black (25%) and Latino (20%) patients. The correlation between preferences against life-prolonging care and the increased likelihood of advance care planning is consistent across ethnic groups.

There are also ethical concerns around how patients reach the decision to agree to a DNR order. One study found that patients wanted intubation in several scenarios, even when they had a Do Not Intubate (DNI) order, which raises a question whether patients with DNR orders may want CPR in some scenarios too. It is possible that providers are having a "leading conversation" with patients or mistakenly leaving crucial information out when discussing DNR.

One study reported that while 88% of young doctor trainees at two hospitals in California in 2013 believed they themselves would ask for a DNR order if they were terminally ill, they are flexible enough to give high intensity care to patients who have not chosen DNR.

There is also the ethical issue of discontinuation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in DNR patients in cases of medical futility. A large survey of Electrophysiology practitioners, the heart specialists who implant pacemakers and ICDs, noted that the practitioners felt that deactivating an ICD was not ethically distinct from withholding CPR thus consistent with DNR. Most felt that deactivating a pacemaker was a separate issue and could not be broadly ethically endorsed. Pacemakers were felt to be unique devices, or ethically taking a role of "keeping a patient alive" like dialysis.

A self-report study from 1999 conducted in Germany and Sweden found that the frequency of resuscitations performed against patients' wishes (per DNR status) was as high as 32.5% among German doctors polled.

Violations and suspensions

Medical professionals can be subjected to ramifications if they knowingly violate a DNR. Each state has established laws and rules that medical providers must follow. For example, in some states within the US, DNRs only apply within a hospital, and can be disregarded in other settings. In these states, EMTs (emergency medical technicians) can therefore administer CPR until reaching the hospital where such laws exist.

If a medical professional knows of a DNR and continues with resuscitation efforts, then they can be sued by the family of the patient. This happens often, with a recent jury awarding $400,000 to the family of a patient for "Wrongful Prolongation of Life" in June 2021. Physicians and their attorneys have argued in some cases that when in doubt, they often err on the side of life-saving measures because they can be potentially reversed later by disconnecting the ventilator. This was the case in 2013 when Beatrice Weisman was wrongfully resuscitated, leading to the family filing a lawsuit.

In the US, bystanders who are not healthcare professionals working in a professional setting are protected under the Good Samaritan Law in most cases. Bystanders are also protected if they begin CPR and use a AED even if there is a DNR tattoo or other evident indicator.

Instead of violating a DNR, anesthesiologists often require suspension of a DNR during palliative care surgeries, such as when a large tumor needs to be removed or a chronic pain issue is being solved. Anesthesiologists argue that the patient is in an unnatural state during surgery with medications, and anesthesiologists should be allowed to reverse this state. This suspension can occur during the pre-op, peri-op, and post-operative period. These suspensions used to be automatic and routine, but this is now viewed as unethical. The Patient Self-Determination Act also prohibits this, as automatic suspension would be a violation of this federal order. However, it is still a common practice for patients to opt for a suspension of their DNR depending on the circumstances of the surgery.

Ethical dilemmas on suspending a DNR occur when a patient with a DNR attempts suicide and the necessary treatment involves ventilation or CPR. In these cases, it has been argued that the principle of beneficence takes precedence over patient autonomy and the DNR can be revoked by the physician. Another dilemma occurs when a medical error happens to a patient with a DNR. If the error is reversible only with CPR or ventilation, there is no consensus if resuscitation should take place or not.

Terminology

DNR and Do Not Resuscitate are common terms in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand. This may be expanded in some regions with the addition of DNI (Do Not Intubate). DNI is specific for not allowing the placement of breathing tubes. In some hospitals DNR alone will imply no intubation, though 98% of intubations are unrelated to cardiac arrest; most intubations are for pneumonia or surgery. Clinically, the vast majority of people requiring resuscitation will require intubation, making a DNI alone problematic. Hospitals sometimes use the expression no code, which refers to the jargon term code, short for Code Blue, an alert to a hospital's resuscitation team. If a patient does want to be resuscitated, their code status may be listed as full code (the opposite of DNR). If the patient only wants to be resuscitated under certain conditions, this is termed partial code.

Some areas of the United States and the United Kingdom include the letter A, as in DNAR, to clarify "Do Not Attempt Resuscitation". This alteration is so that it is not presumed by the patient or family that an attempt at resuscitation will be successful.

As noted above in Less care for DNR patients, the word "resuscitation" has grown to include many treatments other than CPR, so DNR has become ambiguous, and authors recommend "No CPR" instead. In the United Kingdom the preferred term is now DNACPR, reflecting that resuscitation is a general term which includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation as well as, for example, the administration of intravenous fluid.

Since the term DNR implies the omission of action, and therefore "giving up", a few authors have advocated for these orders to be retermed Allow Natural Death. Others say AND is ambiguous whether it would allow morphine, antibiotics, hydration or other treatments as part of a natural death. New Zealand and Australia, and some hospitals in the UK, use the term NFR or Not For Resuscitation. Typically these abbreviations are not punctuated, e.g., DNR rather than D.N.R.

Resuscitation orders, or lack thereof, can also be referred to in the United States as a part of Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST), Physician's Orders on Scope of Treatment (POST) or Transportable Physician Orders for Patient Preferences (TPOPP) orders, typically created with input from next of kin when the patient or client is not able to communicate their wishes.

Another synonymous term is "not to be resuscitated" (NTBR).

In 2004 the internal telephone number for cardiac arrests in all UK hospitals was standardised to 2222; in 2017 the European Board of Anaesthesiology (EBA, European Resuscitation Council (ERC), and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESAIC) issued a joint statement recommending this practice across all European hospitals. Current UK practice is for resuscitation recommendations to be standalone orders (such as DNACPR) or embedded within broader emergency care and treatment plans (ECTPs), such as the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT).

Usage by country

DNR documents are widespread in some countries and unavailable in others. In countries where a DNR is unavailable, the decision to end resuscitation is made solely by physicians.

A 2016 paper reports a survey of small numbers of doctors in numerous countries, asking "how often do you discuss decisions about resuscitation with patients and/or their family?" and "How do you communicate these decisions to other doctors in your institution?" Some countries had multiple respondents, who did not always act the same, as shown below. There was also a question "Does national guidance exist for making resuscitation decisions in your country?" but the concept of "guidance" had no consistent definition. For example, in the US, four respondents said yes, and two said no.

| Country/Location | Discuss with patient or family | Tell other doctors the decision |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Most | Written |

| Australia | Most, half | Oral+notes+pre-printed,(2) notes |

| Austria | Half | Notes |

| Barbados | Half | Oral+notes |

| Belgium | Half, rarely | Notes+electronic |

| Brazil | Most | Oral+notes |

| Brunei | Rarely | Oral+notes |

| Canada | Always, most | Oral+notes, oral+notes+electronic, notes+pre-printed |

| Colombia | Half | Oral |

| Cuba | Always | Oral |

| Denmark | Most | Electronic |

| France | Most | Pre-printed |

| Germany | Always | Oral+notes+electronic |

| Hong Kong | Always, half | Notes+pre-printed, oral+notes+pre-printed |

| Hungary | Rarely | Oral |

| Iceland | Rarely | Notes+electronic |

| India | Always | Notes, oral, oral+notes |

| Ireland | Most, rarely | Notes (2) |

| Israel | Most, half | Oral+notes,(2) notes |

| Japan | Most, half | Oral, notes |

| Lebanon | Most | Oral+notes+electronic |

| Malaysia | Rarely | Notes |

| Malta | Most | Notes |

| New Zealand | Always | Pre-printed |

| Netherlands | Half | Electronic (3) |

| Norway | Always, rarely | Oral, notes+electronic |

| Pakistan | Always | Notes+electronic |

| Poland | Always, most | Oral+notes, notes+pre-printed |

| Puerto Rico | Always | Pre-printed |

| Saudi Arabia | Always, most | Pre-printed, notes+electronic, oral |

| Singapore | Always, most, half | Pre-printed (2), oral+notes+pre-printed, oral+notes+electronic, oral+pre-printed |

| South Africa | Rarely | Oral+notes |

| South Korea | Always | Pre-printed |

| Spain | Always, most | Pre-printed, oral+notes+electronic, oral+notes+pre-printed |

| Sri Lanka | Most | Notes |

| Sweden | Most | Oral+notes+pre-printed+electronic |

| Switzerland | Most, half | Oral+notes+pre-printed, oral+notes+other |

| Taiwan | Half, rarely | Notes+pre-printed+other, oral |

| UAE | Half | Oral+notes |

| Uganda | Always | Notes |

| USA | Always, most | Notes, electronic, oral+electronic, oral+notes+electronic, oral+notes+pre-printed+electronic |

Australia

In Australia, Do Not Resuscitate orders are covered by legislation on a state-by-state basis.

In Victoria, a Refusal of Medical Treatment certificate is a legal means to refuse medical treatments of current medical conditions. It does not apply to palliative care (reasonable pain relief; food and drink). An Advanced Care Directive legally defines the medical treatments that a person may choose to receive (or not to receive) in various defined circumstances. It can be used to refuse resuscitation, so as to avoid needless suffering.

In NSW, a Resuscitation Plan is a medically authorised order to use or withhold resuscitation measures, and which documents other aspects of treatment relevant at end of life. Such plans are only valid for patients of a doctor who is a NSW Health staff member. The plan allows for the refusal of any and all life-sustaining treatments, the advance refusal for a time of future incapacity, and the decision to move to purely palliative care.

Brazil

There is no formally recognized protocol for creating and respecting DNR orders in Brazil's healthcare delivery system. The legality of not administering resuscitation procedures for terminally ill patients has not been clearly defined, leading many providers to practice caution around withholding CPR.

Although DNR orders have not been institutionalized in Brazil there has been a significant amount of dialogue around the ethical question of whether or not to withhold resuscitation interventions. In the past two decades the Federal Medical Board of Brazil published two resolutions, CFM 1.805/2006 and CFM 1.995/2012, which address therapeutic limitations in terminally ill patients as well as advanced directives. A recent study also showed that in Brazil's healthcare system CPR is being withheld in scenarios of terminal illness or multiple comorbidities at rates similar to those in North America.

Canada

Do not resuscitate orders are similar to those used in the United States. In 1995, the Canadian Medical Association, Canadian Hospital Association, Canadian Nursing Association, and Catholic Health Association of Canada worked with the Canadian Bar Association to clarify and create a Joint Statement on Resuscitative Interventions guideline for use to determine when and how DNR orders are assigned. DNR orders must be discussed by doctors with the patient or patient agents or patient's significant others. Unilateral DNR by medical professionals can only be used if the patient is in a vegetative state.

France

In 2005, France implemented its "Patients' Rights and End of Life Care" act. This act allows the withholding/withdrawal of life support treatment and as well as the intensified usage of certain medications that can quicken the action of death. This act also specifies the requirements of the act.

The "Patients' Rights and End of Life Care" Act includes three main measures. First, it prohibits the continuation of futile medical treatments. Secondly, it empowers the right to palliative care that may also include the intensification of the doses of certain medications that can result in the shortening the patient's life span. Lastly, it strengthens the principle of patient autonomy. If the patient is unable to make a decision, the discussion, thus, goes to a trusted third party.

Hong Kong

Starting in 2000, the Medical Council of Hong Kong has taken the position that advance directives should be recognized. A Law Reform Commission consultation from 2004 to 2006 resulted in a recommendation that legislation be passed in support of advance directives. However, as of 2019 no consensus had been reached on legislation.

The Hong Kong Hospital Authority has adopted a set of forms which its doctors will recognize if properly completed. However, their recognition at private hospitals is less clear.

Israel

In Israel, it is possible to sign a DNR form as long as the patient is at least 17 years of age, dying, and aware of their actions.

Italy

In Italy DNR is included in the Italian law no. 219 of December 22, 2017, "Disposizioni Anticipate di Trattamento" or DAT, also called "biotestamento". The law no.219 "Rules on informed consent and advance treatment provisions", reaffirm the freedom of choice of the individual and make concrete the right to health protection, respecting the dignity of the person and the quality of life. The DAT are the provisions that every person of age and capable of understanding and wanting can express regarding the acceptance or rejection of certain diagnostic tests or therapeutic choices and individual health treatments, in anticipation of a possible future inability to self-determine. To be valid, the DATs must have been drawn up only after the person has acquired adequate medical information on the consequences of the choices he intends to make through the DAT. With the entry into force of law 219/2017, every person of age and capable of understanding and willing can draw up his DAT. Furthermore, the DATs must be drawn up with: public act authenticated private writing simple private deed delivered personally to the registry office of the municipality of residence or to the health structures of the regions that have regulated the DAT Due to particular physical conditions of disability, the DAT can be expressed through video recording or with devices that allow the person with disabilities to communicate. The DATs do not expire. They can be renewed, modified or revoked at any time, with the same forms in which they can be drawn up. With the DAT it is also possible to appoint a trustee, as long as he is of age and capable of understanding and willing, who is called to represent the signatory of the DAT who has become incapable in relations with the doctor and health facilities. With the Decree of 22 March 2018, the Ministry of Health established a national database for the registration of advance treatment provisions. Without the expression of any preference by the patient, Physicians must attempt to resuscitate all patients regardless of familial wishes.

Japan

In Japan, DNR orders are known as Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR). Currently, there are no laws or guidelines in place regarding DNAR orders but they are still routinely used. A request to withdraw from life support can be completed by the patient or a surrogate. In addition, it is common for Japanese doctors and nurses to be involved in the decision-making process for the DNAR form.

Jordan

DNRs are not recognized by Jordan. Physicians attempt to resuscitate all patients regardless of individual or familial wishes.

Nigeria

There is no formally accepted protocol for DNRs in Nigeria's healthcare delivery system. Written wills may act as a good guide in many end of life scenarios, but often physicians and/or patients' families will act as the decision makers. As quoted in a 2016 article on Advanced Directives in Nigeria, "everything derives from communal values, the common good, the social goals, traditional practices, cooperative virtues and social relationship. Individuals do not exist in a vacuum but within a web of social and cultural relationships." It is important to note that there are vast cultural differences and perspectives on end of life within Nigeria itself between regions and communities of different ancestry.

Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia patients cannot legally sign a DNR, but a DNR can be accepted by order of the primary physician in case of terminally ill patients.

Taiwan

In Taiwan, patients sign their own DNR orders, and are required to do so to receive hospice care. However, one study looking at insights into Chinese perspectives on DNR showed that the majority of DNR orders in Taiwan were signed by surrogates. Typically doctors discuss the issue of DNR with the patients family rather than the patient themselves. In Taiwan, there are two separate types of DNR forms: DNR-P which the patient themselves sign and DNR-S in which a designated surrogate can sign. Typically, the time period between signing the DNR and death is very short, showing that signing a DNR in Taiwan is typically delayed. Two witnesses must also be present in order for a DNR to be signed.

DNR orders have been legal in Taiwan since June 2000 and were enacted by the Hospice and Palliative Regulation. Also included in the Hospice and Palliative Regulation is the requirement to inform a patient of their terminal condition, however, the requirement is not explicitly defined leading to interpretation of exact truth telling.

United Arab Emirates

The UAE have laws forcing healthcare staff to resuscitate a patient even if the patient has a DNR or does not wish to live. There are penalties for breaching the laws.

United Kingdom

England

In England, CPR is presumed in the event of a cardiac arrest unless a do not resuscitate order is in place. If they have capacity as defined under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 the patient may decline resuscitation. Patients may also specify their wishes and/or devolve their decision-making to a proxy using an advance directive, which are commonly referred to as 'Living Wills', or an emergency care and treatment plan (ECTP), such as ReSPECT. Discussion between patient and doctor is integral to decisions made in advance directives and ECTPs, where resuscitation recommendations should be made within a more holistic consideration of all treatment options. Patients and relatives cannot demand treatment (including CPR) which the doctor believes is futile and in this situation, it is their doctor's duty to act in their 'best interest', whether that means continuing or discontinuing treatment, using their clinical judgment. If the patient lacks capacity, relatives will often be asked for their opinion in order to form a 'best interest' view of what the individual's views would have been (prior to losing capacity). Evaluation of ReSPECT (an ECTP) found that resuscitation status remained a central component of conversations, and that there was variability in the discussion of other emergency treatments.

In 2020 the Care Quality Commission found that residents of care homes had been given inappropriate orders of Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) without notice to residents or their families, causing avoidable deaths. In 2021, the Mencap charity found that people with learning disabilities also had inappropriate DNACPR orders. Medical providers have said that any discussion with patients and families is not in reference to consent to resuscitation and instead should be an explanation. The UK's regulatory body for doctors, the General Medical Council, provides clear guidance on the implementation and discussion of DNACPR decisions, and the obligation to communicate these decisions effectively was established by legal precedent in 2015.

Scotland

In Scotland, the terminology used is "Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation" or "DNACPR". There is a single policy used across all of NHS Scotland. The legal standing is similar to that in England and Wales, in that CPR is viewed as a treatment and, although there is a general presumption that CPR will be performed in the case of cardiac arrest, this is not the case if it is viewed by the treating clinician to be futile. Patients and families cannot demand CPR to be performed if it is felt to be futile (as with any medical treatment) and a DNACPR can be issued despite disagreement, although it is good practice to involve all parties in the discussion.

As in England and Wales, inappropriate orders have been given to individuals who had no medical reason for them, such as a deaf man who received a DNACPR order in 2021 due to "communication difficulties."

Wales

Wales has its own national DNACPR policy, 'Sharing and Involving'. They use the term 'Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation' or 'DNACPR'. They also have an active public information campaigns, which includes the website 'TalkCPR'

United States

In the United States the documentation is especially complicated in that each state accepts different forms, and advance directives also known as living wills may not be accepted by EMS as legally valid forms. If a patient has a living will that specifies the patient requests DNR but does not have a properly filled out state-sponsored form that is co-signed by a physician, EMS may attempt resuscitation.

The DNR decision by patients was first litigated in 1976 in In re Quinlan. The New Jersey Supreme Court upheld the right of Karen Ann Quinlan's parents to order her removal from artificial ventilation. In 1991 Congress passed into law the Patient Self-Determination Act that mandated hospitals honor an person's decision in their healthcare. Forty-nine states currently permit the next of kin to make medical decisions of incapacitated relatives, the exception being Missouri. Missouri has a Living Will Statute that requires two witnesses to any signed advance directive that results in a DNR/DNI code status in the hospital.

In the United States, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) will not be performed if a valid written DNR order is present. Many states do not recognize living wills or health care proxies in the prehospital setting and prehospital personnel in those areas may be required to initiate resuscitation measures unless a specific state-sponsored form is properly filled out and cosigned by a physician.

Legal precedent for the right to refuse medical interventions

There are three notable cases which set the baseline for patient's rights to refuse medical intervention:

- Karen Quinlan, a 21-year-old woman, was in a persistent vegetative state after experiencing two 15-minute apneic periods secondary to drug use. After a year without improvement her father requested that life support be withdrawn. The hospital refused and this culminated in a court case. The trial court sided with the hospital, however the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed the decision. This was the first of multiple state level decisions pre-empting the Cruzan case which established the non-religious (there were other prior rulings regarding Jehovah's Witnesses) right to refuse care and extended that right to incapacitated patients via their guardians. It also established that court cases are not needed to terminate care when there is concordance between the stakeholders in the decision (Guardian, Clinician, Ethics Committees). It also shifted the focus from the right to seek care to the right to die. Mrs. Quinlan survived for 9 years after mechanical ventilation was discontinued.

- Nancy Cruzan was a 31-year-old woman who was in a persistent vegetative state after a motor vehicle accident that caused brain damage. Her family asked that life support be stopped after 4 years without any improvement. The hospital refused without a court order, and the family sued to obtain one. The trial court sided with the family concluding that the state could not override her wishes. This ruling was appealed to and reversed by the Mississippi Supreme Court. This case was ultimately heard by the United States Supreme Court, which affirmed the right of competent individuals to refuse medical treatment and established standards for refusal of treatment for an incompetent person.

- Theresa "Terri" Schiavo was a 27-year-old woman who experienced cardiac arrest and was resuscitated successfully. She was in a persistent vegetative state thereafter. After 8 years in this state without recovery, her husband decided to have her feeding tube removed. Schiavo's parents disagreed and the case that ensued ultimately was heard by the Florida Supreme Court which ruled that remaining alive would not respect her wishes. The United States Supreme Court affirmed that decision and refused to hear the case. This case affirmed the right of a patient to refuse care that is not in their best interests even when incapacitated.

See also

References

- 4

- 5

- ^ "Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) decisions". nhs.uk. 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- ^ "Medical Definition of NO CODE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- ^ "Do-not-resuscitate order: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ Richardson DK, Zive D, Daya M, Newgard CD (April 2013). "The impact of early do not resuscitate (DNR) orders on patient care and outcomes following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest". Resuscitation. 84 (4): 483–7. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.327. PMID 22940596.

- Santonocito C, Ristagno G, Gullo A, Weil MH (February 2013). "Do-not-resuscitate order: a view throughout the world". Journal of Critical Care. 28 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.07.005. PMID 22981534.

- Downar J, Luk T, Sibbald RW, Santini T, Mikhael J, Berman H, Hawryluck L (June 2011). "Why do patients agree to a "Do not resuscitate" or "Full code" order? Perspectives of medical inpatients". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 26 (6): 582–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1616-2. PMC 3101966. PMID 21222172.

- Anderson WG, Chase R, Pantilat SZ, Tulsky JA, Auerbach AD (April 2011). "Code status discussions between attending hospitalist physicians and medical patients at hospital admission". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 26 (4): 359–66. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1568-6. PMC 3055965. PMID 21104036.

- Ginn, D.; Zitner, D. (1995). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Not for all terminally ill patients". Canadian Family Physician. 41: 649–657. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 2146529. PMID 7787495.

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. (March 2019). "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 139 (10): e56 – e528. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000659. PMID 30700139.

- ^ "National Reports by Year". MyCares.net. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ COALITION for COMPASSIONATE CARE of CALIFORNIA (2010). "CPR/DNR" (PDF). UCLA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-03. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ WV Center for End of Life Care; WV Department of Health and Human Services (2016). "DNR Card (Do Not Resuscitate)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ "Understanding Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) Orders - Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital". www.brighamandwomensfaulkner.org. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ^ Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, Kreuter W, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA, Stapleton RD (July 2009). "Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810245. PMC 2917337. PMID 19571280.

- Carew HT, Zhang W, Rea TD (June 2007). "Chronic health conditions and survival after out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest". Heart. 93 (6): 728–31. doi:10.1136/hrt.2006.103895. PMC 1955210. PMID 17309904.

- ^ Merchant RM, Berg RA, Yang L, Becker LB, Groeneveld PW, Chan PS (January 2014). "Hospital variation in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest". Journal of the American Heart Association. 3 (1): e000400. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000400. PMC 3959682. PMID 24487717.

- Bruckel JT, Wong SL, Chan PS, Bradley SM, Nallamothu BK (October 2017). "Patterns of Resuscitation Care and Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in Patients With Advanced Cancer". Journal of Oncology Practice. 13 (10): e821 – e830. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.020404. PMC 5640412. PMID 28763260.

- Abbo ED, Yuen TC, Buhrmester L, Geocadin R, Volandes AE, Siddique J, Edelson DP (January 2013). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcomes in hospitalized community-dwelling individuals and nursing home residents based on activities of daily living". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 61 (1): 34–9. doi:10.1111/jgs.12068. PMID 23311551. S2CID 36483449.

- Søholm H, Bro-Jeppesen J, Lippert FK, Køber L, Wanscher M, Kjaergaard J, Hassager C (March 2014). "Resuscitation of patients suffering from sudden cardiac arrests in nursing homes is not futile". Resuscitation. 85 (3): 369–75. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.033. PMID 24269866.

- Ullman, Edward A.; Sylvia, Brett; McGhee, Jonathan; Anzalone, Brendan; Fisher, Jonathan (2007-07-01). "Lack of Early Defibrillation Capability and Automated External Defibrillators in Nursing Homes". Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 8 (6). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag: 413–415. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2007.04.001. ISSN 1525-8610. PMID 17619041.

- ^ Fendler TJ, Spertus JA, Kennedy KF, Chen LM, Perman SM, Chan PS (2015-09-22). "Alignment of Do-Not-Resuscitate Status With Patients' Likelihood of Favorable Neurological Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". JAMA. 314 (12): 1264–71. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.11069. PMC 4701196. PMID 26393849.

- Boland LL, Satterlee PA, Hokanson JS, Strauss CE, Yost D (January–March 2015). "Chest Compression Injuries Detected via Routine Post-arrest Care in Patients Who Survive to Admission after Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest". Prehospital Emergency Care. 19 (1): 23–30. doi:10.3109/10903127.2014.936636. PMID 25076024. S2CID 9438700.

- "CPR Review - Keeping It Real". HEARTSAVER (BLS Training Site) CPR/AED & First Aid (Bellevue, NE). Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- "CPR Breaking Bones". EMTLIFE. 25 May 2011. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Katz, Douglas I.; Polyak, Meg; Coughlan, Daniel; Nichols, Meliné; Roche, Alexis (2009-01-01). Laureys, Steven; Schiff, Nicholas D.; Owen, Adrian M. (eds.). "Natural history of recovery from brain injury after prolonged disorders of consciousness: outcome of patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation with 1–4 year follow-up". Coma Science: Clinical and Ethical Implications. 177. Elsevier: 73–88.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Giacino, Joseph T.; Katz, Douglas I.; Schiff, Nicholas D.; Whyte, John; Ashman, Eric J.; Ashwal, Stephen; Barbano, Richard; Hammond, Flora M.; Laureys, Steven (2018-08-08). "Practice guideline update recommendations summary: Disorders of consciousness". Neurology. 91 (10): 450–460. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005926. ISSN 0028-3878. PMC 6139814. PMID 30089618.

- The ranges given in the text above represent outcomes inside and outside of hospitals:

- In US hospitals a study of 12,500 survivors after CPR, 2000–2009, found: 1% more survivors of CPR were in comas than before CPR (3% before, 4% after), 5% more survivors were dependent on other people, and 5% more had moderate mental problems but were still independent.

- Outside hospitals, half a percent more survivors were in comas after CPR (0.5% before, 1% after), 10% more survivors were dependent on other people because of mental problems, and 21% more had moderate mental problems which still let them stay independent. This study covered 419 survivors of CPR in Copenhagen in 2007-2011. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.033 and works cited.

- ^ "Part 8: Post-Cardiac Arrest Care – ECC Guidelines, section 11". Resuscitation Science, Section 11. 2015.

- Bossaert; et al. (2015). "European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 11. The ethics of resuscitation and end-of-life decisions". Resuscitation. 95: 302–11. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.033. hdl:10067/1303020151162165141. PMID 26477419. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- Joseph L, Chan PS, Bradley SM, Zhou Y, Graham G, Jones PG, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Girotra S (September 2017). "Temporal Changes in the Racial Gap in Survival After In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". JAMA Cardiology. 2 (9): 976–984. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2403. PMC 5710174. PMID 28793138.

- Breu AC (October 2018). "Clinician-Patient Discussions of Successful CPR-The Vegetable Clause". JAMA Internal Medicine. 178 (10): 1299–1300. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4066. PMID 30128558. S2CID 52047054.

- ^ Orioles A, Morrison WE, Rossano JW, Shore PM, Hasz RD, Martiner AC, Berg RA, Nadkarni VM (December 2013). "An under-recognized benefit of cardiopulmonary resuscitation: organ transplantation". Critical Care Medicine. 41 (12): 2794–9. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829a7202. PMID 23949474. S2CID 30112782.

- Sandroni C, D'Arrigo S, Callaway CW, Cariou A, Dragancea I, Taccone FS, Antonelli M (November 2016). "The rate of brain death and organ donation in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (11): 1661–1671. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4549-3. PMC 5069310. PMID 27699457.

- Tolle, Susan W.; Olszewski, Elizabeth; Schmidt, Terri A.; Zive, Dana; Fromme, Erik K. (2012-01-04). "POLST Registry Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Other Patient Treatment Preferences". JAMA. 307 (1): 34–35. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1956. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 22215159.

- Horwitz LI (January 2016). "Implications of Including Do-Not-Resuscitate Status in Hospital Mortality Measures". JAMA Internal Medicine. 176 (1): 105–6. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6845. PMID 26662729.

- ^ Smith CB, Bunch O'Neill L (October 2008). "Do not resuscitate does not mean do not treat: how palliative care and other modalities can help facilitate communication about goals of care in advanced illness". The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York. 75 (5): 460–5. doi:10.1002/msj.20076. PMID 18828169.

- ^ Yuen JK, Reid MC, Fetters MD (July 2011). "Hospital do-not-resuscitate orders: why they have failed and how to fix them". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 26 (7): 791–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1632-x. PMC 3138592. PMID 21286839.

- Schwarze ML, Redmann AJ, Alexander GC, Brasel KJ (January 2013). "Surgeons expect patients to buy-in to postoperative life support preoperatively: results of a national survey". Critical Care Medicine. 41 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826a4650. PMC 3624612. PMID 23222269.

- Hawkes, C (2020). "Development of the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT)" (PDF). Resuscitation. 148: 98–107. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.01.003. PMID 31945422. S2CID 210703171.

- ^ Eli, K (2020). "Secondary care consultant clinicians' experiences of conducting emergency care and treatment planning conversations in England: an interview-based analysis". BMJ Open. 20 (1): e031633. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031633. PMC 7044868. PMID 31964663.

- ^ Malhi S (2019-05-05). "The term 'do not resuscitate' should be laid to rest". Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- Marco CA, Mozeleski E, Mann D, Holbrook MB, Serpico MR, Holyoke A, Ginting K, Ahmed A (March 2018). "Advance directives in emergency medicine: Patient perspectives and application to clinical scenarios". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 36 (3): 516–518. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.08.002. PMID 28784259.

- "Resuscitation, Item 7.1, Prognostication". CPR & ECC Guidelines. The American Heart Association.

Part 3: Ethical Issues – ECC Guidelines, Timing of Prognostication in Post–Cardiac Arrest Adults

- ^ "Statement on Controlled Organ Donation After Circulatory Death". www.asahq.org. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- "Determination of Death Act - Uniform Law Commission". www.uniformlaws.org. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Non-Heart-Beating Transplantation II: The Scientific and Ethical Basis for Practice and Protocols (2000). Non-Heart-Beating Organ Transplantation: Practice and Protocols. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-06641-9. PMID 25077239.

- ^ Burns JP, Truog RD (December 2007). "Futility: a concept in evolution". Chest. 132 (6): 1987–93. doi:10.1378/chest.07-1441. PMID 18079232.

- Armstrong (2014). "Medical Futility and Nonbeneficial Interventions". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 89 (12): 1599–607. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.08.017. PMID 25441398.

- ^ Steinhauser (2000). "Factors Considered Important at the End of Life by Patients, Family, Physicians, and Other Care Providers" (PDF). JAMA. 284 (19): 2476–82. doi:10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. PMID 11074777.

- Reinke LF, Uman J, Udris EM, Moss BR, Au DH (December 2013). "Preferences for death and dying among veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 30 (8): 768–72. doi:10.1177/1049909112471579. PMID 23298873. S2CID 24353297.

- Brunner-La Rocca HP, Rickenbacher P, Muzzarelli S, Schindler R, Maeder MT, Jeker U, et al. (March 2012). "End-of-life preferences of elderly patients with chronic heart failure". European Heart Journal. 33 (6): 752–9. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr404. PMID 22067089.

- Sabatino, Charlie (1 October 2015). "Myths and Facts About Health Care Advance Directives". American Bar Association. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Coleman D (2013-07-23). "Full Written Public Comment: Disability Related Concerns About POLST". Not Dead Yet. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ^ Jesus JE, Allen MB, Michael GE, Donnino MW, Grossman SA, Hale CP, Breu AC, Bracey A, O'Connor JL, Fisher J (July 2013). "Preferences for resuscitation and intubation among patients with do-not-resuscitate/do-not-intubate orders". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (7): 658–65. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.04.010. PMID 23809316.

- ^ Resuscitation Council UK. "ReSPECT for Patients and Carers". Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Perkins, GD (2021). "Evaluation of the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment". Health Services and Delivery Research.

- ^ "DNR Guidelines for Medical ID Wearers". www.americanmedical-id.com. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Holt, Gregory E.; Sarmento, Bianca; Kett, Daniel; Goodman, Kenneth W. (2017-11-30). "An Unconscious Patient with a DNR Tattoo". New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (22): 2192–2193. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1713344. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 29171810.

- Cooper, Lori; Aronowitz, Paul (October 2012). "DNR Tattoos: A Cautionary Tale". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 27 (10): 1383. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2059-8. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 3445694. PMID 22549297.

- Dugan D, Riseman J (July 2015). "Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders in an Operating Room Setting #292". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 18 (7): 638–9. doi:10.1089/jpm.2015.0163. PMID 26091418.

- Rubin E, Courtwright A (November 2013). "Medical futility procedures: what more do we need to know?". Chest. 144 (5): 1707–1711. doi:10.1378/chest.13-1240. PMID 24189864.

- Swetz KM, Burkle CM, Berge KH, Lanier WL (July 2014). "Ten common questions (and their answers) on medical futility". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 89 (7): 943–59. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.02.005. PMID 24726213.

- Garrido MM, Harrington ST, Prigerson HG (December 2014). "End-of-life treatment preferences: a key to reducing ethnic/racial disparities in advance care planning?". Cancer. 120 (24): 3981–6. doi:10.1002/cncr.28970. PMC 4257859. PMID 25145489.

- ^ Capone's paper, and the original by Jesus et al. say the patients were asked about CPR, but the questionnaire shows they were only asked whether they wanted intubation in various scenarios. This is an example of doctors using the term resuscitation to cover other treatments than CPR.

- Capone RA (March 2014). "Problems with DNR and DNI orders". Ethics & Medics. 39 (3): 1–3.

- Jesus (2013). "Supplemental Appendix of Preferences for Resuscitation and Intubation..." (PDF). Ars.els-CDN.

- Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Fong A, Kraemer H (2014-05-28). "Do unto others: doctors' personal end-of-life resuscitation preferences and their attitudes toward advance directives". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e98246. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...998246P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098246. PMC 4037207. PMID 24869673.

- Pfeifer M, Quill TE, Periyakoil VJ (2014). "Physicians provide high-intensity end-of-life care for patients, but "no code" for themselves". Medical Ethics Advisor. 30 (10).

- Daeschler M, Verdino RJ, Caplan AL, Kirkpatrick JN (August 2015). "Defibrillator Deactivation against a Patient's Wishes: Perspectives of Electrophysiology Practitioners". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 38 (8): 917–24. doi:10.1111/pace.12614. PMID 25683098. S2CID 45445345.

- Richter, Jörg; Eisemann, Martin R (1999-11-01). "The compliance of doctors and nurses with do-not-resuscitate orders in Germany and Sweden". Resuscitation. 42 (3): 203–209. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(99)00092-1. ISSN 0300-9572. PMID 10625161.

- ^ "'Do Not Resuscitate' orders and bystander CPR: Can you get in trouble?". www.cprseattle.com. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- "Jury Awards $400,000 in "Wrongful Prolongation of Life" Lawsuit | Physician's Weekly". www.physiciansweekly.com. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- Span, Paula (2017-04-10). "The Patients Were Saved. That's Why the Families Are Suing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- Jackson, Stephen (2015-03-01). "Perioperative Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders". AMA Journal of Ethics. 17 (3): 229–235. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.3.nlit1-1503. ISSN 2376-6980. PMID 25813589.

- Humble MB (November 2014). "Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Suicide Attempts: What Is the Moral Duty of the Physician?". The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly. 14 (4): 661–71. doi:10.5840/ncbq201414469.

- Hébert PC, Selby D (April 2014). "Should a reversible, but lethal, incident not be treated when a patient has a do-not-resuscitate order?". CMAJ. 186 (7): 528–30. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111772. PMC 3986316. PMID 23630240.

- "DNR/DNI/AND | CureSearch". curesearch.org. 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Breu, Anthony C.; Herzig, Shoshana J. (October 2014). "Differentiating DNI from DNR: Combating code status conflation: Differentiating DNI From DNR". Journal of Hospital Medicine. 9 (10): 669–670. doi:10.1002/jhm.2234. PMC 5240781. PMID 24978058.

- Esteban (2002). "Characteristics and Outcomes in Adult Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation<SUBTITLE>A 28-Day International Study</SUBTITLE>" (PDF). JAMA. 287 (3): 345–55. doi:10.1001/jama.287.3.345. PMID 11790214.

- Downar, James; Luk, Tracy; Sibbald, Robert W.; Santini, Tatiana; Mikhael, Joseph; Berman, Hershl; Hawryluck, Laura (June 2011). "Why Do Patients Agree to a "Do Not Resuscitate" or "Full Code" Order? Perspectives of Medical Inpatients". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 26 (6): 582–587. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1616-2. PMC 3101966. PMID 21222172.

- Resuscitation Fluids | NEJM

- Mockford C, Fritz Z, George R, Court R, Grove A, Clarke B, Field R, Perkins GD (March 2015). "Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) orders: a systematic review of the barriers and facilitators of decision-making and implementation". Resuscitation. 88: 99–113. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.016. PMID 25433293.

- Meyer C (20 October 2020). "Allow Natural Death — An Alternative To DNR?". Rockford, Michigan: Hospice Patients Alliance. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- Sinclair, Christian (2009-03-05). "Do Not (Attempt) Resuscitation vs. Allow Natural Death". Pallimed.org.

- Youngner, S. J.; Chen, Y.-Y. (2008-12-01). ""Allow natural death" is not equivalent to "do not resuscitate": a response". Journal of Medical Ethics. 34 (12): 887–888. doi:10.1136/jme.2008.024570. ISSN 0306-6800. PMID 19065754. S2CID 26867470.

- Pollak AN, Edgerly D, McKenna K, Vitberg DA, et al. (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons) (2017). Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 540. ISBN 978-1-284-10690-9.

- Vincent JL, Van Vooren JP (December 2002). "". Revue Médicale de Bruxelles. 23 (6): 497–9. PMID 12584945.

- ""Establishing a standard crash call telephone number in hospitals"". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- Uniweb, Tibo C. "ERC | Bringing resuscitation to the world". www.erc.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Gibbs AJ, malyon AC, Fritz ZB (June 2016). "Themes and variations: An exploratory international investigation into resuscitation decision-making". Resuscitation. 103: 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.01.020. PMC 4879149. PMID 26976676.

- "Respect for the right to choose - Resources". Dying with dignity, Victoria. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-02-18. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- "Using resuscitation plans in end of life decisions" (PDF). Government of New South Wales Health Department. 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ^ Putzel, Elzio Luiz; Hilleshein, Klisman Drescher; Bonamigo, Elcio Luiz (December 2016). "Ordem de não reanimar pacientes em fase terminal sob a perspectiva de médicos". Revista Bioética. 24 (3): 596–602. doi:10.1590/1983-80422016243159. ISSN 1983-8042.

- ^ "Do Not Resuscitate Orders". Princess Margaret Hospital d. Archived from the original on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ^ Pennec, Sophie; Monnier, Alain; Pontone, Silvia; Aubry, Régis (2012-12-03). "End-of-life medical decisions in France: a death certificate follow-up survey 5 years after the 2005 act of parliament on patients' rights and end of life". BMC Palliative Care. 11: 25. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-11-25. ISSN 1472-684X. PMC 3543844. PMID 23206428.

- "Substitute Decision-making and Advance Directives in Relation to Medical Treatment - Executive Summary" (PDF). Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong. 16 August 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- "LCQ15: Advance directives in relation to medical treatment". www.info.gov.hk. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- "Guidance for HA Clinicians on Advance Directives in Adults" (PDF). Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. 2 July 2020.

- "Senior Community Legal Information Centre - Health & care - Advance Directives - What is an "Advance Directive"?". Senior CLIC. 13 May 2022. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- "Advance Medical Directives and Power of Attorney". State of Israel Ministry of Health. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- it:law no.219 https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/1/16/18G00006/sg

- Nakagawa, Yoshihide; Inokuchi, Sadaki; Kobayashi, Nobuo; Ohkubo, Yoshinobu (April 2017). "Do not attempt resuscitation order in Japan". Acute Medicine & Surgery. 4 (3): 286–292. doi:10.1002/ams2.271. PMC 5674456. PMID 29123876.

- Rubulotta, F.; Rubulotta, G.; Santonocito, C.; Ferla, L.; Celestre, C.; Occhipinti, G.; Ramsay, G. (March 2010). "End-of-life care is still a challenge for Italy". Minerva Anestesiologica. 76 (3): 203–208. ISSN 1827-1596. PMID 20203548.

- Cherniack, E P (2002-10-01). "Increasing use of DNR orders in the elderly worldwide: whose choice is it?". Journal of Medical Ethics. 28 (5): 303–307. doi:10.1136/jme.28.5.303. PMC 1733661. PMID 12356958.

- "Mideast med-school camp: divided by conflict, united by profession". The Globe and Mail. August 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-08-21. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

In hospitals in Jordan and Palestine, neither families nor social workers are allowed in the operating room to observe resuscitation, says Mohamad Yousef, a sixth-year medical student from Jordan. There are also no DNRs. "If it was within the law, I would always work to save a patient, even if they didn't want me to," he says.

- Jegede, Ayodele Samuel; Adegoke, Olufunke Olufunsho (November 2016). "Advance Directive in End of Life Decision-Making among the Yoruba of South-Western Nigeria". BEOnline. 3 (4): 41–67. doi:10.20541/beonline.2016.0008. ISSN 2315-6422. PMC 5363404. PMID 28344984.

- Fan SY, Wang YW, Lin IM (October 2018). "Allow natural death versus do-not-resuscitate: titles, information contents, outcomes, and the considerations related to do-not-resuscitate decision". BMC Palliative Care. 17 (1): 114. doi:10.1186/s12904-018-0367-4. PMC 6180419. PMID 30305068.

- Blank, Robert H. (May 2011). "End-of-Life Decision Making across Cultures". The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 39 (2): 201–214. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00589.x. ISSN 1073-1105. PMID 21561515. S2CID 857118.

- ^ Wen, Kuei-Yen; Lin, Ya-Chin; Cheng, Ju-Feng; Chou, Pei-Chun; Wei, Chih-Hsin; Chen, Yun-Fang; Sun, Jia-Ling (September 2013). "Insights into Chinese perspectives on do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders from an examination of DNR order form completeness for cancer patients". Supportive Care in Cancer. 21 (9): 2593–2598. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1827-2. ISSN 0941-4355. PMC 3728434. PMID 23653012.

- Al Amir S (25 September 2011). "Nurses deny knowledge of 'do not resuscitate' order in patient's death". The National. United Arab Emirates. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Booth, Robert (2020-12-03). "'Do not resuscitate' orders caused potentially avoidable deaths, regulator finds". Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- Tapper, James (2021-02-13). "Fury at 'do not resuscitate' notices given to Covid patients with learning disabilities". The Guardian. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- "Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A joint statement from the British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing" (PDF). Resus.org.uk. Resuscitation Council (UK). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)". www.gmc-uk.org. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- "DNACPR orders – advice and obligations". mdujournal.themdu.com. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- Scottish Government (May 2010). "Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR): Integrated Adult Policy" (PDF). NHS Scotland.

- "Deaf man given DNR order without his consent". 4 June 2021.

- "Wales Sharing and Involving DNACPR Policy".

- "Talk CPR Videos and Resources". Archived from the original on 2016-01-20.

- Eckberg E (April 1998). "The continuing ethical dilemma of the do-not-resuscitate order". AORN Journal. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

The right to refuse or terminate medical treatment began evolving in 1976 with the case of Karen Ann Quinlan v New Jersey (70NJ10, 355 A2d, 647 ). This spawned subsequent cases leading to the use of the DNR order.(4) In 1991, the Patient Self-Determination Act mandated hospitals ensure that a patient's right to make personal health care decisions is upheld. According to the act, a patient has the right to refuse treatment, as well as the right to refuse resuscitative measures.(5) This right usually is accomplished by the use of the DNR order.

- "DO NOT RESUSCITATE – ADVANCE DIRECTIVES FOR EMS Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". State of California Emergency Medical Services Authority. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-08-23. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

# What if the EMT cannot find the DNR form or evidence of a MedicAlert medallion? Will they withhold resuscitative measures if my family asks them to? No. EMS personnel are taught to proceed with CPR when needed, unless they are absolutely certain that a qualified DNR advance directive exists for that patient. If, after spending a reasonable (very short) amount of time looking for the form or medallion, they do not see it, they will proceed with lifesaving measures.

- "Frequently Asked Questions re: DNR's". New York State Department of Health. 1999-12-30. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

May EMS providers accept living wills or health care proxies? A living will or health care proxy is NOT valid in the prehospital setting

- Tiegreen, Tim. "Case Study - Matter of Quinlan". Center for Practical Bioethics. Retrieved 2021-09-12.

- "Case Study - The Case of Nancy Cruzan". Center for Practical Bioethics. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- Hook, C. Christopher; Mueller, Paul S. (2005-11-01). "The Terri Schiavo Saga: The Making of a Tragedy and Lessons Learned". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 80 (11): 1449–1460. doi:10.4065/80.11.1449. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 16295025.

External links

- "Do Not Resuscitate Orders". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Decisions Relating to Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation". Resuscitation Council (UK). Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Resuscitation Council UK ReSPECT process