Single parents in the United States have become more common since the second half of the 20th century.

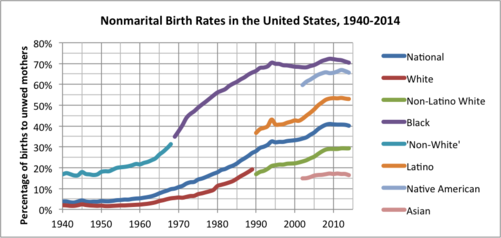

In the United States, since the 1960s, there has been an increase in the number of children living with a single parent. The jump was caused by an increase in births to unmarried women and by the increasing prevalence of divorces among couples. In 2010, 40.7% of births in the US were to unmarried women. In 2000, 11% of children were living with parents who had never been married, 15.6% of children lived with a divorced parent, and 1.2% lived with a parent who was widowed.

The results of the 2010 United States Census showed that 27% of children live with one parent, consistent with the emerging trend noted in 2000. The most recent data of December 2011 shows approximately 13.7 million single parents in the U.S. Mississippi leads the nation with the highest percent of births to unmarried mothers with 54% in 2014, followed by Louisiana, New Mexico, Florida and South Carolina.

In 2006, 12.9 million families in the US were headed by a single parent, 80% of which were headed by a female.

The newest census bureau reports that between 1960 and 2016, the percentage of children living in families with two parents decreased from 88 to 69. Of those 50.7 million children living in families with two parents, 47.7 million live with two married parents and 3.0 million live with two unmarried parents.

The percentage of children living with single parents increased substantially in the United States during the second half of the 20th century. According to a 2013 Child Trends study, only 9% of children lived with single parents in the 1960s—a figure that increased to 28% in 2012. The main cause of single parent families are high rates of divorce and non-marital childbearing.

According to a 2019 study from Pew Research Center, the United States has the world's highest rate of children living in single-parent households.

Single mothers

In the United States, 80% of single parents are mothers. Among this percentage of single mothers: 45% of single mothers are currently divorced or separated, 1.7% are widowed, 34% of single mothers never have been married. This is in contrast to earlier decades, where having a child outside of marriage and/or being a single mother was not prominent. Census information from 1960 tells us that in that year, only nine percent of children lived in single parent families. Today four out of every ten children are born to an unwed mother.

The prevalence of single mothers as primary caregiver is a part of traditional parenting trends between mothers and fathers. Data supports these claims, showing that in comparison to men, women are doing more than two-thirds of all child caring and in some cases one hundred percent. Of approximately 11 million single-parent homes in 2020, more than 80 percent were headed by single mothers. This disproportionate statistic has been well-documented in multiple country contexts all around the world. The United States Census Bureau found that today, one in four children under the age of 18, a total of 17.4 million are being raised without a father at all. Women all around the world have been perpetually socialized to adhere to traditional gender roles that place the majority of responsibility for childcare upon them.

The cultural definition of a mother's role contributes to the preference of mother as primary caregiver. The "motherhood mandate" describes the societal expectations that good mothers should be available to their children as much as possible. In addition to their traditional protective and nurturing role, single mothers may have to play the role of family provider as well; since men are the breadwinners of the traditional family, in the absence of the child support or social benefits the mother must fulfill this role whilst also providing adequate parentage.

Because of this dual role, in the United States, 80% of single mothers are employed, of which 50% are full-time workers and 30% are part-time. Many employed single mothers rely on childcare facilities to care for their children while they are away at work. Linked to the rising prevalence of single parenting is the increasing quality of health care, and there have been findings of positive developmental effects with modern childcare.

It is not uncommon that the mother will become actively involved with the childcare program as to compensate for leaving her children under the care of others. Working single mothers may also rely on the help from fictive kin, who provide for the children while the mother is at her job. All of these factors contribute to a well-documented heightened likelihood for single-parent, female-headed households to experience poverty.

Single mothers are one of the poorest populations, many of them vulnerable to homelessness. In the United States, nearly half (45%) of single mothers and their children live below the poverty line, also referred to as the poverty threshold. They lack the financial resources to support their children when the birth father is unresponsive. Many seek assistance through living with another adult, perhaps a relative, fictive kin, or significant other, and divorced mothers who remarry have fewer financial struggles than unmarried single mothers, who cannot work for longer periods of time without shirking their child-caring responsibilities. Unmarried mothers are thus more likely to cohabit with another adult. Many of the jobs worked by, or are available to women, are not sufficient and do not bring in enough income for the mother and her children; this is common in the United States and other countries all over the world.

Single fathers

In the United States today, there are nearly 13.6 million single parents raising over 21 million children. Single fathers are far less common than single mothers, constituting 16% of single-parent families. According to Single Parent Magazine, the number of single fathers has increased by 60% in the last ten years, and is one of the fastest growing family situations in the United States. 60% of single fathers are divorced, by far the most common cause of this family situation. In addition, there is an increasing trend of men having children through surrogate mothers and raising them alone. While fathers are not normally seen as primary caregivers, statistics show that 90% of single-fathers are employed, and 72% have a full-time job.

Little research has been done to suggest the hardships of the "single father as a caretaker" relationship; however, a great deal has been done on the hardships of a single-parent household. Single-parent households tend to find difficulty with the lack of help they receive. More often than not a single parent finds it difficult to find help because there is a lack of support, whether it be a second parent or other family members. This tends to put a strain on not only the parent but also the relationship between the parent and their child. Furthermore, dependency is a hardship that many parents find difficult to overcome.

As the single parent becomes closer to their child, the child grows more dependent upon that parent. This dependency, while common, may reach far past childhood, damaging the child due to their lack of independence from their parent. "Social isolation of single parents might be a stress factor that they transmit to children. Another explanation may be that the parents do not have the time needed to support and supervise their children. This can have a negative impact on the child."

Just as above, it has been found that little 'specific' research to the positives of the father as a single parent has been done; however, there are various proven pros that accompany single parenting. One proven statistic about single fathers states that a single father tends to use more positive parenting techniques than a married father. As far as non-specific pros, a strong bond tends to be formed between parent and child in single-parenting situations, allowing for an increase in maturity and closeness in the household. Gender roles are also less likely to be enforced in a single parent home because the work and chores are more likely to be shared among all individuals rather than specifically a male or female.

Living arrangements for single parents

The newest census that the majority of America's 73.7 million children under age 18 live in families with two parents (69 percent), according to new statistics released from the U.S. Census Bureau. This is compared to other types of living arrangements, such as living with grandparents or having a single parent. The second most common family arrangement is children living with a single mother, at 23 percent. These statistics come from the Census Bureau's annual America's Families and Living Arrangements table package. Many single parents co-residence with their parents, more commonly single mothers do this. Studies show that in the US, single parents are more likely to live with their own parents, perhaps because of the additional financial burden of young children.

Single parent adoption

Single parent adoption is legal in all 50 states, a relatively recent occurrence as California's State Department of Social Welfare was the first to permit it in the 1960s. Though, the process is arduous, and even next to impossible through some agencies. Adoption agencies have strict rules about what kinds of people they allow, and most are thorough in checking the adopter's background. An estimated 5–10% of all adoptions in the U.S. are by single persons.

References

- *Grove, Robert D.; Hetzel, Alice M. (1968). Vital Statistics Rates in the United States 1940–1960 (PDF) (Report). Public Health Service Publication. Vol. 1677. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, U.S. Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics. p. 185.

- Ventura, Stephanie J.; Bachrach, Christine A. (October 18, 2000). Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States, 1940–99 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. pp. 28–31.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Park, Melissa M. (February 12, 2002). Births: Final Data for 2000 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Park, Melissa M.; Sutton, Paul D. (December 18, 2002). Births: Final Data for 2001 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 51. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 47.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Munson, Martha L. (December 17, 2003). Births: Final Data for 2002 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 52. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Munson, Martha L. (September 8, 2005). Births: Final Data for 2003 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 54. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 52.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon (September 29, 2006). Births: Final Data for 2004 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 55. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Munson, Martha L. (December 5, 2007). Births: Final Data for 2005 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 56. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J. (January 7, 2009). Births: Final Data for 2006 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 54.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (August 9, 2010). Births: Final Data for 2007 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (December 8, 2010). Births: Final Data for 2008 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 59. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J.; Wilson, Elizabeth C. (November 3, 2011). Births: Final Data for 2009 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 60. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Wilson, Elizabeth C.; Mathews, T.J. (August 28, 2012). Births: Final Data for 2010 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 45.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Mathews, T.J. (June 28, 2013). Births: Final Data for 2011 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 43.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C. (December 30, 2013). Births: Final Data for 2012 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 41.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C.; Mathews, T.J. (January 15, 2015). Births: Final Data for 2013 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 40.

- Hamilton, Brady E.; Martin, Joyce A.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C.; Mathews, T.J. (December 23, 2015). Births: Final Data for 2014 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. pp. 7 & 41.

- "FastStats – Births and Natality". August 8, 2018.

- O'Hare, Bill (July 2001). "The Rise – and Fall? – of Single-Parent Families". Population Today. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- "Single Parent Success Foundation". America's Children: Key National Indicators of Well-being. www.childstats.gov. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- "More Young Adults are Living in Their Parents' Home, Census Bureau Reports" (Press release). United States Census Bureau. November 3, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- "The Most Important Statistics About Single Parents". The Spruce. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- "The Number of Births to Unmarried Mothers in Massachusetts is Higher than You Think". Infinity Law Group. March 28, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- Current Population Survey, 2006 Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement (PDF), Washington: United States Bureau of the Census, 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2013

- Navarro, Mireya (September 5, 2008). "The Bachelor Life Includes a Family". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Majority of Children Live With Two Parents, Census Bureau Reports". The United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- Amato, Paul R., Sarah Patterson, and Brett Beattie. "Single-Parent Households And Children'S Educational Achievement: A State-Level Analysis." Social Science Research 53.(2015): 191–202. SocINDEX with Full Text. Web. March 18. 2017.

- "U.S. has world's highest rate of children living in single-parent households". Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "What Do Single Parent Statistics Tell Us?". Single Parent Center. August 3, 2011. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- "Population Survey". The United States Census Bureau. The United States Census Bureau. 2014.

- ^ "America's Families and Living Arrangements: 2020". United States Census Bureau. 2020.

- Steil, Janice (2001). "Family Forms and Member Well- Being: A Research Agenda for the Decade of Behavior". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 25 (4): 344–363. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00034. S2CID 145770529.

- Ruppanner, Leah; Pixley, Joy (2012). "Work to Family and Family to Work Spillover: The Implications of Childcare Policy and Maximum Work Hour Legislation". Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 33 (3): 283–297. doi:10.1007/s10834-012-9303-6. hdl:11343/282530. S2CID 143581687.

- Pierce, Latoya; Herlihy, Barbara (2013). "The Experience of Wellness for Counselor Education Doctoral Students Who are Mothers in the Southeastern Region of the United States". Journal of International Women's Studies. 14 (3): 108–120 – via Proquest.

- Nomaguchi, Kei; Brown, Susan (2011). "Parental Strains and Rewards Among Mothers: The Role of Education". Journal of Marriage and Family. 73 (3): 621–636. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00835.x. PMC 3489180. PMID 23136449.

- ^ Pander, Shanta; Zhan, Min (2007). "Postsecondary Education, Marital Status, and Economic Well Being of Women with Children". Social Development Issues. 29 (1): 1–26.

- Damaske, Sarah (2017). "Single Mother Families and Employment, Race, and Poverty in Changing Economic Times". Social Science Research. 62 (February 2017): 120–133. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.08.008. PMC 5300078. PMID 28126093.

- Neckerman, Kathryn M. (2004). Social Inequality. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-87154-621-0.

- Rosalind, Duncan, Simon; Edwards; Edwards, Rosalind; University, Simon Duncan University of Bradford; Rosalind Edwards South Bank (November 5, 2013). Single Mothers In International Context: Mothers Or Workers?. Routledge. ISBN 9781134227945.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ludden, Jennifer (June 19, 2012). "Single Dads By Choice: More Men Going It Alone". Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Erica (February 6, 2003). "Children in Single Parent Homes and Emotional Problems". The Hilltop. Howard University. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- "Better Health Channel". Online Article. State Government of Victoria. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- Hyunjoon, Park (April 28, 2016). "Living Arrangements of Single Parents and Their Children in South Korea". Marriage & Family Review. 52 (1–2): 89–105. doi:10.1080/01494929.2015.1073653. S2CID 146600799.

- Cake-Hanson-Cormell (2001). "Single Parent Adoptions: Why Not?". Adopting.org. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Ashe, Nancy S. "Singled Out: A Bad Rap for Single Adoptive Parents". Article. Adopting.org. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- "Single Parent Adoption". Adoption Services. Retrieved April 23, 2014.