A switched-mode power supply (SMPS), also called switching-mode power supply, switch-mode power supply, switched power supply, or simply switcher, is an electronic power supply that incorporates a switching regulator to convert electrical power efficiently.

Like other power supplies, a SMPS transfers power from a DC or AC source (often mains power, see AC adapter) to DC loads, such as a personal computer, while converting voltage and current characteristics. Unlike a linear power supply, the pass transistor of a switching-mode supply continually switches between low-dissipation, full-on and full-off states, and spends very little time in the high-dissipation transitions, which minimizes wasted energy. Voltage regulation is achieved by varying the ratio of on-to-off time (also known as duty cycle). In contrast, a linear power supply regulates the output voltage by continually dissipating power in the pass transistor. The switched-mode power supply's higher electrical efficiency is an important advantage.

Switched-mode power supplies can also be substantially smaller and lighter than a linear supply because the transformer can be much smaller. This is because it operates at a high switching frequency which ranges from several hundred kHz to several MHz in contrast to the 50 or 60 Hz mains frequency used by the transformer in a linear power supply. Despite the reduced transformer size, the power supply topology and electromagnetic compatibility requirements in commercial designs result in a usually much greater component count and corresponding circuit complexity.

Switching regulators are used as replacements for linear regulators when higher efficiency, smaller size or lighter weight is required. They are, however, more complicated; switching currents can cause electrical noise problems if not carefully suppressed, and simple designs may have a poor power factor.

History

- 1836

- Induction coils use switches to generate high voltages.

- 1910

- An inductive discharge ignition system invented by Charles F. Kettering and his company Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company (Delco) goes into production for Cadillac. The Kettering ignition system is a mechanically switched version of a flyback boost converter; the transformer is the ignition coil. Variations of this ignition system were used in all non-diesel internal combustion engines until the 1960s when it began to be replaced first by solid-state electronically switched versions, then capacitive discharge ignition systems.

- 1926

- On 23 June, British inventor Philip Ray Coursey applies for a patent in his country and United States, for his "Electrical Condenser". The patent mentions high frequency welding and furnaces, among other uses.

- c. 1932

- Electromechanical relays are used to stabilize the voltage output of generators. See Voltage regulator § Electromechanical regulators.

- c. 1936

- Car radios used electromechanical vibrators to transform the 6 V battery supply to a suitable plate voltage for the vacuum tubes.

- 1959

- Transistor oscillation and rectifying converter power supply system U.S. patent 3,040,271 is filed by Joseph E. Murphy and Francis J. Starzec, from General Motors Company

- 1960s

- The Apollo Guidance Computer, developed in the early 1960s by the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory for NASA's ambitious Moon missions (1966–1972), incorporated early switched-mode power supplies.

- c. 1967

- Bob Widlar of Fairchild Semiconductor designs the μA723 IC voltage regulator. One of its applications is as a switched-mode regulator.

- 1970

- Tektronix starts using high-efficiency power supplies in its 7000-series oscilloscopes produced from about 1970 to 1995.

- 1970

- Robert Boschert develops simpler, low-cost switched-mode power supply circuits. By 1977, Boschert Inc. grew to a 650-person company. After a series of mergers, acquisitions, and spin offs (Computer Products, Zytec, Artesyn, Emerson Electric) the company is now part of Advanced Energy.

- 1972

- HP-35, Hewlett-Packard's first pocket calculator, is introduced with transistor switching power supply for light-emitting diodes, clocks, timing, ROM, and registers.

- 1973

- Xerox uses switching power supplies in the Alto minicomputer

- 1976

- Robert Mammano, a co-founder of Silicon General Semiconductors, develops the first integrated circuit for SMPS control, model SG1524. After a series of mergers and acquisitions (Linfinity, Symetricom, Microsemi), the company is now part of Microchip Technology.

- 1977

- The Apple II is designed with a switched-mode power supply.

- 1980

- The HP8662A 10 kHz–1.28 GHz synthesized signal generator was designed with a switched-mode power supply.

Explanation

A linear power supply (non-SMPS) uses a linear regulator to provide the desired output voltage by dissipating power in ohmic losses (e.g., in a resistor or in the collector–emitter region of a pass transistor in its active mode). A linear regulator regulates either output voltage or current by dissipating the electric power in the form of heat, and hence its maximum power efficiency is voltage-out/voltage-in since the volt difference is wasted.

In contrast, a SMPS changes output voltage and current by switching ideally lossless storage elements, such as inductors and capacitors, between different electrical configurations. Ideal switching elements (approximated by transistors operated outside of their active mode) have no resistance when "on" and carry no current when "off", and so converters with ideal components would operate with 100% efficiency (i.e., all input power is delivered to the load; no power is wasted as dissipated heat). In reality, these ideal components do not exist, so a switching power supply cannot be 100% efficient, but it is still a significant improvement in efficiency over a linear regulator.

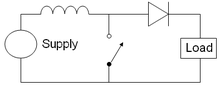

For example, if a DC source, an inductor, a switch, and the corresponding electrical ground are placed in series and the switch is driven by a square wave, the peak-to-peak voltage of the waveform measured across the switch can exceed the input voltage from the DC source. This is because the inductor responds to changes in current by inducing its own voltage to counter the change in current, and this voltage adds to the source voltage while the switch is open. If a diode-and-capacitor combination is placed in parallel to the switch, the peak voltage can be stored in the capacitor, and the capacitor can be used as a DC source with an output voltage greater than the DC voltage driving the circuit. This boost converter acts like a step-up transformer for DC signals. A buck–boost converter works in a similar manner, but yields an output voltage which is opposite in polarity to the input voltage. Other buck circuits exist to boost the average output current with a reduction of voltage.

In a SMPS, the output current flow depends on the input power signal, the storage elements and circuit topologies used, and also on the pattern used (e.g., pulse-width modulation with an adjustable duty cycle) to drive the switching elements. The spectral density of these switching waveforms has energy concentrated at relatively high frequencies. As such, switching transients and ripple introduced onto the output waveforms can be filtered with a small LC filter.

Advantages and disadvantages

The main advantage of the switching power supply is greater efficiency (up to c. 98–99%) and lower heat generation than linear regulators because the switching transistor dissipates little power when acting as a switch.

Other advantages include smaller size, and lighter weight from the elimination of heavy and expensive line-frequency transformers. Standby power loss is often much less than transformers.

Disadvantages include greater complexity, the generation of high-amplitude, high-frequency energy that the low-pass filter must block to avoid electromagnetic interference (EMI), a ripple voltage at the switching frequency and its harmonic frequencies.

Very low-cost SMPSs may couple electrical switching noise back onto the mains power line, causing interference with devices connected to the same phase, such as A/V equipment. Non-power-factor-corrected SMPSs also cause harmonic distortion.

SMPS and linear power supply comparison

There are two main types of regulated power supplies available: SMPS and linear. The following table compares linear with switching power supplies in general:

| Linear power supply | Switching power supply | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size and weight | 0.12 W/cm, 88 W/kg | Smaller than linear power supply. Compared to linear, a SMPS that is 20 kHz is 1/4, 100–200 kHz is 1/8, and 200 kHz–1 MHz types can be even smaller. | A transformer's power handling capacity of given size and weight increases with frequency provided that hysteresis losses can be kept down. Therefore, a higher operating frequency means either a higher capacity or smaller transformer. |

| Output voltage | With transformer used, any voltages available; if transformerless, limited to what can be achieved with a voltage doubler. In case of transformer input voltage range limited by acceptable dissipation of regulator on high input and turns ratio on low input, limiting input range. | Any voltages available, limited only by transistor breakdown voltages in many circuits. Voltage varies little with load. | An SMPS can usually cope with wider variation of input before the output voltage changes. Universal or "wide input" power supplies, which work with mains voltages from 90 to 250 V, are common. More specialized designs could accept even wider input voltage range. |

| Efficiency, heat, and power dissipation | Efficiency largely depends on voltage difference between input and output; output voltage is regulated by dissipating excess power as heat resulting in a typical efficiency of 30–40%. | 70-85% efficiency, but can reach 90%. | They can be used together to form a compound regulator with a linear regulator placed after the SMPS to achieve an efficiency of 60-65%. |

| Complexity | Linear voltage-regulating circuit and usually noise-filtering capacitors; usually a simpler circuit (and simpler feedback loop stability criteria) than switched-mode circuits. | Consists of a controller IC, one or several power transistors and diodes as well as a power transformer, inductors, and filter capacitors. Some design complexities present (reducing noise/interference; extra limitations on maximum ratings of transistors at high switching speeds) not found in linear regulator circuits. | In switched-mode mains (AC-to-DC) supplies, multiple voltages can be generated by one transformer core, but that can introduce design/use complications: for example, it may place minimum output current restrictions on one output. For this SMPSs have to use duty cycle control. One of the outputs has to be chosen to feed the voltage regulation feedback loop (usually 3.3 V or 5 V loads are more fussy about their supply voltages than the 12 V loads, so this drives the decision as to which feeds the feedback loop. The other outputs usually track the regulated one pretty well). Both need a careful selection of their transformers. Due to the high operating frequencies in SMPSs, the stray inductance and capacitance of the printed circuit board traces become important. |

| Radio frequency interference | Mild high-frequency interference may be generated by AC rectifier diodes under heavy current loading, while most other supply types produce no high-frequency interference. Some mains hum induction into unshielded cables, problematic for low-level audio signals. | EMI/RFI produced due to the current being switched on and off sharply. Therefore, EMI filters and RF shielding are needed to reduce the disruptive interference. | Long wires between the components may reduce the high-frequency filter efficiency provided by the capacitors at the inlet and outlet. Stable switching frequency may be important. |

| Electronic noise at the output terminals | Linear regulators generally have excellent rejection of AC line ripple and are generally lower noise than switched-mode converters. | Noisier due to the switching frequency of the SMPS. An unfiltered output may cause glitches in digital circuits or noise in audio circuits. | This can be suppressed with capacitors and other filtering circuitry in the output stage. With a switched-mode PSU the switching frequency can be chosen to keep the noise out of the circuits working frequency band (e.g., for audio systems above the range of human hearing) |

| Electronic noise at the input terminals | Causes harmonic distortion to the input AC, but relatively little or no high-frequency noise. | Very low-cost SMPS may couple electrical switching noise back onto the mains power line, causing interference with A/V equipment connected to the same phase. Non-power-factor-corrected SMPSs also cause harmonic distortion. | This can be prevented if a (properly earthed) EMI/RFI filter is connected between the input terminals and the bridge rectifier. |

| Acoustic noise | Faint, usually inaudible mains hum, usually due to vibration of windings in the transformer or magnetostriction. | Usually inaudible to most humans, unless they have a fan or are unloaded/malfunctioning, or use a switching frequency within the audio range, or the laminations of the coil vibrate at a subharmonic of the operating frequency. | The operating frequency of an unloaded SMPS is sometimes in the audible human range and may sound subjectively quite loud for people whose hearing is very sensitive to the relevant frequency range. |

| Power factor | Low because current is drawn from the mains at the peaks of the voltage sinusoid, unless a choke-input or resistor-input circuit follows the rectifier (now rare). | Around 0.5–0.6 without correction. 0.7–0.75 with passive correction and can exceed 0.99 with active correction. | Active/passive power factor correction in the SMPS can offset this problem and are even required by some electric regulation authorities, particularly in the EU. The internal resistance of low-power transformers in linear power supplies usually limits the peak current each cycle and thus gives a better power factor than many switched-mode power supplies that directly rectify the mains with little series resistance. |

| Inrush current | Large current when mains-powered linear power supply equipment is switched on until magnetic flux of transformer stabilizes and capacitors charge completely, unless a slow-start circuit is used. | Extremely large peak "in-rush" surge current limited only by the impedance of the input supply and any series resistance to the filter capacitors. | Empty filter capacitors initially draw large amounts of current as they charge up, with larger capacitors drawing larger amounts of peak current. Being many times above the normal operating current, this greatly stresses components subject to the surge, complicates fuse selection to avoid nuisance blowing and may cause problems with equipment employing overcurrent protection such as uninterruptible power supplies. Mitigated by use of a suitable soft-start circuit or series resistor. |

| Risk of electric shock | Supplies with transformers isolate the incoming power supply from the powered device and so allow metalwork of the enclosure to be grounded safely. Dangerous if primary/secondary insulation breaks down, unlikely with reasonable design. Transformerless mains-operated supply are not isolated and therefore dangerous when exposed. In both linear and switch-mode the mains, and possibly the output voltages, are hazardous and must be well-isolated. | Common rail of equipment (including casing) is energized to half the mains voltage, but at high impedance, unless equipment is earthed/grounded or doesn't contain EMI/RFI filtering at the input terminals. | Due to regulations concerning EMI/RFI radiation, many SMPS contain EMI/RFI filtering at the input stage consisting of capacitors and inductors before the bridge rectifier. Two capacitors are connected in series with the Live and Neutral rails with the Earth connection in between the two capacitors. This forms a capacitive divider that energizes the common rail at half mains voltage. Its high impedance current source can provide a tingling or a 'bite' to the operator or can be exploited to light an Earth Fault LED. However, this current may cause nuisance tripping on the most sensitive residual-current devices. In power supplies without a ground pin (like USB charger) there is EMI/RFI capacitor placed between primary and secondary side. It can also provide some very mild tingling sensation but it's safe to the user. |

| Risk of equipment damage | Very low, unless a short occurs between the primary and secondary windings or the regulator fails by shorting internally. | Can fail so as to make output voltage very high. Stress on capacitors may cause them to explode. Can in some cases destroy input stages in amplifiers if floating voltage exceeds transistor base-emitter breakdown voltage, causing the transistor's gain to drop and noise levels to increase. Mitigated by good failsafe design. Failure of a component in the SMPS itself can cause further damage to other PSU components; can be difficult to troubleshoot. | The floating voltage is caused by capacitors bridging the primary and secondary sides of the power supply. Connection to earthed equipment will cause a momentary (and potentially destructive) spike in current at the connector as the voltage at the secondary side of the capacitor equalizes to earth potential. |

Theory of operation

A: Bridge rectifier;

B: input filter capacitors;

Between B and C: heat sink for switching active devices of primary voltage;

C: transformer:

Between C and D: heat sink for switching active devices of at least five secondary voltages, per the ATX specification;

D: output filter coil for the secondary with the largest power rating. In close proximity, filter coils for the other secondaries;

E: output filter capacitors.

The coil and large rectangular yellow capacitor below the bridge rectifier form an EMI filter and are not part of the main circuit board.

Input rectifier stage

If the SMPS has an AC input, then the first stage is to convert the input to DC. This is called 'rectification'. An SMPS with a DC input does not require this stage. In some power supplies (mostly computer ATX power supplies), the rectifier circuit can be configured as a voltage doubler by the addition of a switch operated either manually or automatically. This feature permits operation from power sources that are normally at 115 VAC or at 230 VAC. The rectifier produces an unregulated DC voltage which is then sent to a large filter capacitor. The current drawn from the mains supply by this rectifier circuit occurs in short pulses around the AC voltage peaks. These pulses have significant high frequency energy which reduces the power factor. To correct for this, many newer SMPS will use a special power factor correction (PFC) circuit to make the input current follow the sinusoidal shape of the AC input voltage, correcting the power factor. Power supplies that use active PFC usually are auto-ranging, supporting input voltages from ~100 VAC – 250 VAC, with no input voltage selector switch.

An SMPS designed for AC input can usually be run from a DC supply, because the DC would pass through the rectifier unchanged. If the power supply is designed for 115 VAC and has no voltage selector switch, the required DC voltage would be 163 VDC (115 × √2). This type of use may be harmful to the rectifier stage, however, as it will only use half of diodes in the rectifier for the full load. This could possibly result in overheating of these components, causing them to fail prematurely. On the other hand, if the power supply has a voltage selector switch, based on the Delon circuit, for 115/230 V (computer ATX power supplies typically are in this category), the selector switch would have to be put in the 230 V position, and the required voltage would be 325 VDC (230 × √2). The diodes in this type of power supply will handle the DC current just fine because they are rated to handle double the nominal input current when operated in the 115 V mode, due to the operation of the voltage doubler. This is because the doubler, when in operation, uses only half of the bridge rectifier and runs twice as much current through it.

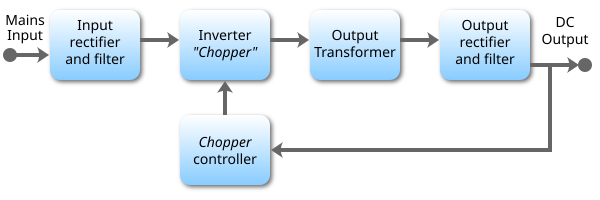

Inverter stage

- This section refers to the block marked chopper in the diagram.

The inverter stage converts DC, whether directly from the input or from the rectifier stage described above, to AC by running it through a power oscillator, whose output transformer is very small with few windings, at a frequency of tens or hundreds of kilohertz. The frequency is usually chosen to be above 20 kHz, to make it inaudible to humans. The switching is implemented as a multistage (to achieve high gain) MOSFET amplifier. MOSFETs are a type of transistor with a low on-resistance and a high current-handling capacity.

Voltage converter and output rectifier

If the output is required to be isolated from the input, as is usually the case in mains power supplies, the inverted AC is used to drive the primary winding of a high-frequency transformer. This converts the voltage up or down to the required output level on its secondary winding. The output transformer in the block diagram serves this purpose.

If a DC output is required, the AC output from the transformer is rectified. For output voltages above ten volts or so, ordinary silicon diodes are commonly used. For lower voltages, Schottky diodes are commonly used as the rectifier elements; they have the advantages of faster recovery times than silicon diodes (allowing low-loss operation at higher frequencies) and a lower voltage drop when conducting. For even lower output voltages, MOSFETs may be used as synchronous rectifiers; compared to Schottky diodes, these have even lower conducting state voltage drops.

The rectified output is then smoothed by a filter consisting of inductors and capacitors. For higher switching frequencies, components with lower capacitance and inductance are needed.

Simpler, non-isolated power supplies contain an inductor instead of a transformer. This type includes boost converters, buck converters, and buck–boost converters. These belong to the simplest class of single input, single output converters which use one inductor and one active switch. The buck converter reduces the input voltage in direct proportion to the ratio of conductive time to the total switching period, called the duty cycle. For example, an ideal buck converter with a 10 V input operating at a 50% duty cycle will produce an average output voltage of 5 V. A feedback control loop is employed to regulate the output voltage by varying the duty cycle to compensate for variations in input voltage. The output voltage of a boost converter is always greater than the input voltage and the buck–boost output voltage is inverted but can be greater than, equal to, or less than the magnitude of its input voltage. There are many variations and extensions to this class of converters but these three form the basis of almost all isolated and non-isolated DC-to-DC converters. By adding a second inductor the Ćuk and SEPIC converters can be implemented, or, by adding additional active switches, various bridge converters can be realized.

Other types of SMPSs use a capacitor–diode voltage multiplier instead of inductors and transformers. These are mostly used for generating high voltages at low currents (Cockcroft-Walton generator). The low voltage variant is called charge pump.

Regulation

A feedback circuit monitors the output voltage and compares it with a reference voltage. Depending on design and safety requirements, the controller may contain an isolation mechanism (such as an opto-coupler) to isolate it from the DC output. Switching supplies in computers, TVs and VCRs have these opto-couplers to tightly control the output voltage.

Open-loop regulators do not have a feedback circuit. Instead, they rely on feeding a constant voltage to the input of the transformer or inductor, and assume that the output will be correct. Regulated designs compensate for the impedance of the transformer or coil. Monopolar designs also compensate for the magnetic hysteresis of the core.

The feedback circuit needs power to run before it can generate power, so an additional non-switching power supply for stand-by is added.

Transformer design

Any switched-mode power supply that gets its power from an AC power line (called an "off-line" converter) requires a transformer for galvanic isolation. Some DC-to-DC converters may also include a transformer, although isolation may not be critical in these cases. SMPS transformers run at high frequencies. Most of the cost savings (and space savings) in off-line power supplies result from the smaller size of the high-frequency transformer compared to the 50/60 Hz transformers formerly used. There are additional design tradeoffs.

The terminal voltage of a transformer is proportional to the product of the core area, magnetic flux, and frequency. By using a much higher frequency, the core area (and so the mass of the core) can be greatly reduced. However, core losses increase at higher frequencies. Cores generally use ferrite material which has a low loss at the high frequencies and high flux densities used. The laminated iron cores of lower-frequency (<400 Hz) transformers would be unacceptably lossy at switching frequencies of a few kilohertz. Also, more energy is lost during transitions of the switching semiconductor at higher frequencies. Furthermore, more attention to the physical layout of the circuit board is required as parasitics become more significant, and the amount of electromagnetic interference will be more pronounced.

Copper loss

Main article: Copper lossAt low frequencies (such as the line frequency of 50 or 60 Hz), designers can usually ignore the skin effect. For these frequencies, the skin effect is only significant when the conductors are large, more than 0.3 inches (7.6 mm) in diameter.

Switching power supplies must pay more attention to the skin effect because it is a source of power loss. At 500 kHz, the skin depth in copper is about 0.003 inches (0.076 mm) – a dimension smaller than the typical wires used in a power supply. The effective resistance of conductors increases, because current concentrates near the surface of the conductor and the inner portion carries less current than at low frequencies.

The skin effect is exacerbated by the harmonics present in the high-speed pulse-width modulation (PWM) switching waveforms. The appropriate skin depth is not just the depth at the fundamental, but also the skin depths at the harmonics.

In addition to the skin effect, there is also a proximity effect, which is another source of power loss.

Power factor

See also: Power factorSimple off-line switched-mode power supplies incorporate a simple full-wave rectifier connected to a large energy-storing capacitor. Such SMPSs draw current from the AC line in short pulses when the mains instantaneous voltage exceeds the voltage across this capacitor. During the remaining portion of the AC cycle the capacitor provides energy to the power supply.

As a result, the input current of such basic switched-mode power supplies has high harmonic content and relatively low power factor. This creates extra load on utility lines, increases heating of building wiring, the utility transformers, and standard AC electric motors, and may cause stability problems in some applications such as in emergency generator systems or aircraft generators. Harmonics can be removed by filtering, but the filters are expensive. Unlike displacement power factor created by linear inductive or capacitive loads, this distortion cannot be corrected by addition of a single linear component. Additional circuits are required to counteract the effect of the brief current pulses. Putting a current regulated boost chopper stage after the off-line rectifier (to charge the storage capacitor) can correct the power factor, but increases the complexity and cost.

In 2001, the European Union put into effect the standard IEC 61000-3-2 to set limits on the harmonics of the AC input current up to the 40th harmonic for equipment above 75 W. The standard defines four classes of equipment depending on its type and current waveform. The most rigorous limits (class D) are established for personal computers, computer monitors, and TV receivers. To comply with these requirements, modern switched-mode power supplies normally include an additional power factor correction (PFC) stage.

Types

Switched-mode power supplies can be classified according to the circuit topology. The most important distinction is between isolated converters and non-isolated ones.

Non-isolated topologies

Non-isolated converters are simplest, with the three basic types using a single inductor for energy storage. In the voltage relation column, D is the duty cycle of the converter, and can vary from 0 to 1. The input voltage (V1) is assumed to be greater than zero; if it is negative, for consistency, negate the output voltage (V2).

| Type | Typical Power [W] | Relative cost | Energy storage | Voltage relation | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buck | 0–1,000 | 1.0 | Single inductor | 0 ≤ Out ≤ In, | Current is continuous at output. |

| Boost | 0–5,000 | 1.0 | Single inductor | Out ≥ In, | Current is continuous at input. |

| Buck–boost | 0–150 | 1.0 | Single inductor | Out ≤ 0, | Current is discontinuous at both input and output. |

| Split-pi (or, boost–buck) | 0–4,500 | >2.0 | Two inductors and three capacitors | Up or down | Bidirectional power control; in or out. |

| Ćuk | Capacitor and two inductors | Any inverted, | Current is continuous at input and output. | ||

| SEPIC | Capacitor and two inductors | Any, | Current is continuous at input. | ||

| Zeta | Capacitor and two inductors | Any, | Current is continuous at output. | ||

| Charge pump / switched capacitor | Capacitors only | No magnetic energy storage is needed to achieve conversion, however high efficiency power processing is normally limited to a discrete set of conversion ratios. |

When equipment is human-accessible, voltage limits of ≤ 30 V (r.m.s.) AC or ≤ 42.4 V peak or ≤ 60 V DC and power limits of 250 VA apply for safety certification (UL, CSA, VDE approval).

The buck, boost, and buck–boost topologies are all strongly related. Input, output and ground come together at one point. One of the three passes through an inductor on the way, while the other two pass through switches. One of the two switches must be active (e.g., a transistor), while the other can be a diode. Sometimes, the topology can be changed simply by re-labeling the connections. A 12 V input, 5 V output buck converter can be converted to a 7 V input, −5 V output buck–boost by grounding the output and taking the output from the ground pin.

Likewise, SEPIC and Zeta converters are both minor rearrangements of the Ćuk converter.

The neutral point clamped (NPC) topology is used in power supplies and active filters and is mentioned here for completeness.

Switchers become less efficient as duty cycles become extremely short. For large voltage changes, a transformer (isolated) topology may be better.

Isolated topologies

All isolated topologies include a transformer, and thus can produce an output of higher or lower voltage than the input by adjusting the turns ratio. For some topologies, multiple windings can be placed on the transformer to produce multiple output voltages. Some converters use the transformer for energy storage, while others use a separate inductor.

| Type | Power [W] |

Relative cost | Input range [V] |

Energy storage | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flyback | 0–250 | 1.0 | 5–600 | Mutual inductors | Isolated form of the buck–boost converter |

| Ringing choke converter (RCC) | 0–150 | 1.0 | 5–600 | Transformer | Low-cost self-oscillating flyback variant |

| Half-forward | 0–250 | 1.2 | 5–500 | Inductor | |

| Forward | 100–200 | 60–200 | Inductor | Isolated form of buck converter | |

| Resonant forward | 0–60 | 1.0 | 60–400 | Inductor and capacitor | Single rail input, unregulated output, high efficiency, low EMI. |

| Push-pull | 100–1,000 | 1.75 | 50–1,000 | Inductor | |

| Half-bridge | 0–2,000 | 1.9 | 50–1,000 | Inductor | |

| Full-bridge | 400–5,000 | >2.0 | 50–1,000 | Inductor | Very efficient use of transformer, used for highest powers |

| Resonant, zero voltage switched | >1,000 | >2.0 | Inductor and capacitor | ||

| Isolated Ćuk | Two capacitors and two inductors |

- ^1 Flyback converter logarithmic control loop behavior might be harder to control than other types.

- ^2 The forward converter has several variants, varying in how the transformer is "reset" to zero magnetic flux every cycle.

Chopper controller: The output voltage is coupled to the input thus very tightly controlled

Quasi-resonant zero-current/zero-voltage switch

In a quasi-resonant zero-current/zero-voltage switch (ZCS/ZVS) "each switch cycle delivers a quantized 'packet' of energy to the converter output, and switch turn-on and turn-off occurs at zero current and voltage, resulting in an essentially lossless switch." Quasi-resonant switching, also known as valley switching, reduces EMI in the power supply by two methods:

- By switching the bipolar switch when the voltage is at a minimum (in the valley) to minimize the hard switching effect that causes EMI.

- By switching when a valley is detected, rather than at a fixed frequency, introduces a natural frequency jitter that spreads the RF emissions spectrum and reduces overall EMI.

Efficiency and EMI

Higher input voltage and synchronous rectification mode makes the conversion process more efficient. The power consumption of the controller also has to be taken into account. Higher switching frequency allows component sizes to be shrunk, but can produce more RFI. A resonant forward converter produces the lowest EMI of any SMPS approach because it uses a soft-switching resonant waveform compared with conventional hard switching.

Failure modes

For failure in switching components, circuit board, etc, see Failure of electronic components.SMPSs tend to be temperature sensitive. For every 10-15 °C beyond 25 °C, failure rate doubles. Most failures can be attributed to improper design and poor component selections.

Power supplies with capacitors that have reached the end of their life or suffer from manufacturing defects such as the capacitor plague will fail eventually. When either the capacitance decreases or the ESR increases, the regulator compensates by increasing the switching frequency, thereby subjecting the switching semiconductors to ever greater thermal stress. Eventually the switching semiconductors fail, usually in a conductive manner. For power supplies without fail-safe protection, this may subject connected loads to the full input voltage and current, and wild oscillations can occur in the output.

Failure of the switching transistor is common. Due to the large switching voltages this transistor must handle (around 325 V for a 230 VAC non-power-factor-corrected mains supply, otherwise usually around 390 V), these transistors often short out, in turn immediately blowing the main internal power fuse.

Power supplies in consumer products are frequently damaged by lightning strikes on power lines as well as internal short circuits caused by insects attracted to the heat and electrostatic fields. Those events may damage any part of the power supply.

Precautions

The main filter capacitor will often store up to 325 volts long after the input power has been disconnected. Not all power supplies contain a small "bleeder" resistor which slowly discharges the capacitor. Contact with this capacitor can result in a severe electrical shock.

The primary and secondary sides may be connected with a capacitor to reduce EMI and compensate for various capacitive couplings in the converter circuit, where the transformer is one. This may result in electric shock in some cases. The current flowing from line or neutral through a 2 kΩ resistor to any accessible part must, according to IEC 60950, be less than 250 μA for IT equipment.

Applications

Switched-mode power supply units (PSUs) in domestic products such as personal computers often have universal inputs, meaning that they can accept power from mains supplies throughout the world, although a manual voltage range switch may be required. Switch-mode power supplies can tolerate a wide range of power frequencies and voltages.

Due to their high volumes mobile phone chargers have always been particularly cost sensitive. The first chargers were linear power supplies, but they quickly moved to the cost-effective ringing choke converter (RCC) SMPS topology, when new levels of efficiency were required. Recently, the demand for even lower no-load power requirements in the application has meant that flyback topology is being used more widely; primary side sensing flyback controllers are also helping to cut the bill of materials (BOM) by removing secondary-side sensing components such as optocouplers.

Switched-mode power supplies are used for DC-to-DC conversion as well. In heavy vehicles that use a nominal 24 VDC cranking supply, 12 V for accessories may be furnished through a DC/DC switch-mode supply. This has the advantage over tapping the battery at the 12 V position (using half the cells) that the entire 12 V load is evenly divided between all cells of the 24 V battery. In industrial settings such as telecommunications racks, bulk power may be distributed at a low DC voltage (e.g. from a battery backup system) and individual equipment items will have DC/DC switched-mode converters to supply required voltages.

A common use for switched-mode power supplies is an extra-low-voltage source for lighting. For this application, they are often called "electronic transformers".

Terminology

The term switch mode was widely used until Motorola claimed ownership of the trademark SWITCHMODE for products aimed at the switching-mode power supply market and started to enforce its trademark. Switching-mode power supply, switching power supply, and switching regulator refer to this type of power supply.

See also

- Auto transformer

- Boost converter

- Buck converter

- Conducted electromagnetic interference

- DC to DC converter

- Inrush current

- Joule thief

- Leakage inductance

- Resonant converter

- Switching amplifier

- Transformer

- Vibrator (electronic)

- 80 Plus

Explanatory notes

- The pass transistor is the avtive device power passes through in route from input to output in the power supply.

Notes

- US 1037492, Kettering, Charles F., "Ignition system", published 2 November 1910, issued 3 September 1912

- US 1754265, Coursey, Philip Ray, "Electrical Condenser", published 23 June 1926, issued 15 April 1930

- ^ "When was the SMPS power supply invented?". electronicspoint.com.

- "Electrical condensers (Open Library)". openlibrary.org.

- "First-Hand:The Story of the Automobile Voltage Regulator - Engineering and Technology History Wiki". ethw.org. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- US 2014869, Teare Jr., Benjamin R. & Whiting, Max A., "Electroresponsive Device", published 15 November 1932, issued 17 September 1935

- "Cadillac model 5-X, a 5-tube supherheterodyne radio, used a synchronous vibrator to generate its B+ supply". Radiomuseum.

- US patent 3040271, "Transistor converter power supply system"

- Ken Shirriff (January 2019). "Inside the Apollo Guidance Computer's core memory". righto.com. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "μA723 Precision Voltage Regulators" (PDF). ti.com. July 1999 .

- DiGiacomo, David (2002-08-02). "Test Equipment and Electronics Information". slack.com. Archived from the original on 2002-08-02.

- "7000 Plugin list". www.kahrs.us. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "7000 SERIES OSCILLOSCOPES FAQ". tek.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- TEKSCOPE 7704 High-Efficiency Power Supply (PDF). March 1971. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- ^ Shirriff, Ken (August 2019). "The Quiet Remaking of Computer Power Supplies: A Half Century Ago Better Transistors And Switching Regulators Revolutionized The Design Of Computer Power Supplies". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- Kilbane, Doris (2009-12-07). "Robert Boschert: A Man Of Many Hats Changes The World Of Power Supplies". Electronic Design. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- "Power Electronics Corporate Genealogy" (PDF). Power Supply Manufacturers' Association.

- "COMPUTER PRODUCTS HAS NEW NAME: ARTESYN". Sun Sentinel. 1998-05-07.

- "COMPUTER PRODUCTS BUYS RIVAL MANUFACTURER". Sun Sentinel. 1986-01-03.

- "jacques-laporte.org - The HP-35's Power unit and other vintage HP calculators". citycable.ch. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Y Combinator's Xerox Alto: restoring the legendary 1970s GUI computer". arstechnica.com. 26 June 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "North American Company Profiles" (PDF). smithsonianchips.si.edu. 2004-03-15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-07. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- Yarow, Jay (2011-05-24). "EXCLUSIVE: Interview With Apple's First CEO Michael Scott". Business Insider.

Rod Holt ... created the switching power supply that allowed us to do a very lightweight computer

- "HP 3048A". hpmemoryproject.org.

- ISL9120 with up to 98% efficiency https://web.archive.org/web/20240330200510/https://www.mouser.de/datasheet/2/698/Renesas_Electronics_03152019_ISL9120IIAZ-TR5696-1823356.pdf

- ADP5302 with up to 98% efficiency https://web.archive.org/web/20240330200705/https://www.mouser.de/datasheet/2/609/ADP5302-3121859.pdf

- LTC 3777 with up to 99% efficiency https://web.archive.org/web/20240330201744/https://www.mouser.de/datasheet/2/609/LTC3777-3125324.pdf

- ^ Sha, Zhanyou; Wang, Xiaojun; Wang, Yanpeng; Ma, Hongtao (2015). Optimal design of switching power supply. Singapore: Wiley, China Electric Power Press. ISBN 978-1-118-79094-6.

- "Energy Savings Opportunity by Increasing Power Supply Efficiency". Archived from the original on 2010-10-25. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- Sha, Zhanyou; Wang, Xiaojun; Wang, Yanpeng; Ma, Hongtao (2015-06-15). Optimal Design of Switching Power Supply. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-79094-6.

- Tabatabaei, Naser Mahdavi; Aghbolaghi, Ali Jafari; Bizon, Nicu; Blaabjerg, Frede (2017-04-05). Reactive Power Control in AC Power Systems: Fundamentals and Current Issues. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-51118-4.

- "How does a usb charger work". Flashlight information.

- "Information about the mild tingling sensation - US". pcsupport.lenovo.com.

- "Ban Looms for External Transformers". Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- "DC Power Production, Delivery and Utilization, An EPRI White Paper" (PDF). Page 9 080317 mydocs.epri.com

- "Notes on the Troubleshooting and Repair of Small Switchmode Power Supplies". Switching between 115 VAC and 230 VAC input. Search the page for "doubler" for more info.

- ^ Foutz, Jerrold. "Switching-Mode Power Supply Design Tutorial Introduction". Archived from the original on 2004-04-06. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Unruh, Roland; Schafmeister, Frank; Böcker, Joachim (November 2020). 11kW, 70kHz LLC Converter Design with Adaptive Input Voltage for 98% Efficiency in an MMC. 2020 IEEE 21st Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL). Aalborg, Denmark: IEEE. doi:10.1109/COMPEL49091.2020.9265771. S2CID 227278364.

- Pressman 1998, p. 306

- ^ ON Semiconductor (July 11, 2002). "SWITCHMODE Power Supplies—Reference Manual and Design Guide" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- "An active power filter implemented with multilevel single-phase NPC converters". 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-11-26. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- "DC-DC Converter Basics". Archived from the original on 2005-12-17. 090112 powerdesigners.com

- "DC-DC CONVERTERS: A PRIMER" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-18. 090112 jaycar.com.au Page 4

- "Heinz Schmidt-Walter". h-da.de.

- Irving, Brian T.; Jovanović, Milan M. (March 2002), Analysis and Design of Self-Oscillating Flyback Converter (PDF), Proc. IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conf. (APEC), pp. 897–903, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-09, retrieved 2009-09-30

- "RDFC topology for linear replacement". Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. 090725 camsemi.com Further information on resonant forward topology for consumer applications

- "Gain Equalization Improves Flyback Performance Page of". 100517 powerelectronics.com

- Marchetti, Robert (2012-08-13). "Comparing dc/dc converters' noise-related performance". EDN. Archived from the original on 2012-09-02. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- Encyclopedia Of Thermal Packaging, Set 2: Thermal Packaging Tools (A 4-volume Set). World Scientific. 2014-10-23. ISBN 978-981-4520-24-9.

- Sha, Zhanyou; Wang, Xiaojun; Wang, Yanpeng; Ma, Hongtao (2015-06-15). Optimal Design of Switching Power Supply. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-79094-6.

- "Bad Capacitors: Information and symptoms". 100211 lowyat.net

- "Estimation of Optimum Value of Y-Capacitor for Reducing Emi in Switch Mode Power Supplies" (PDF). 15 March 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-15.

References

- Pressman, Abraham I. (1998), Switching Power Supply Design (2nd ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-052236-7

Further reading

- Basso, Christophe (2008), Switch-Mode Power Supplies: SPICE Simulations and Practical Designs, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-150858-2

- Basso, Christophe (2012), Designing Control Loops for Linear and Switching Power Supplies: A Tutorial Guide, Artech House, ISBN 978-1608075577

- Brown, Marty (2001), Power Supply Cookbook (2nd ed.), Newnes, ISBN 0-7506-7329-X

- Erickson, Robert W.; Maksimović, Dragan (2001), Fundamentals of Power Electronics (Second ed.), Springer, ISBN 0-7923-7270-0

- Liu, Mingliang (2006), Demystifying Switched-Capacitor Circuits, Elsevier, ISBN 0-7506-7907-7

- Luo, Fang Lin; Ye, Hong (2004), Advanced DC/DC Converters, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-1956-0

- Luo, Fang Lin; Ye, Hong; Rashid, Muhammad H. (2005), Power Digital Power Electronics and Applications, Elsevier, ISBN 0-12-088757-6

- Maniktala, Sanjaya (2004), Switching Power Supply Design and Optimization, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-143483-6

- Maniktala, Sanjaya (2006), Switching Power Supplies A to Z, Newnes/Elsevier, ISBN 0-7506-7970-0

- Maniktala, Sanjaya (2007), Troubleshooting Switching Power Converters: A Hands-on Guide, Newnes/Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-7506-8421-7

- Mohan, Ned; Undeland, Tore M.; Robbins, William P. (2002), Power Electronics : Converters, Applications, and Design, Wiley, ISBN 0-471-22693-9

- Nelson, Carl (1986), LT1070 design Manual, vol. AN19, Linear Technology Application Note giving an extensive introduction in Buck, Boost, CUK, Inverter applications. (download as PDF from http://www.linear.com/designtools/app_notes.php)

- Pressman, Abraham I.; Billings, Keith; Morey, Taylor (2009), Switching Power Supply Design (Third ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-148272-1

- Rashid, Muhammad H. (2003), Power Electronics: Circuits, Devices, and Applications, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-122815-3

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Switched-mode power supplies at Wikimedia Commons

- Switching Power Supply Topologies Poster - Texas Instruments

- Load Power Sources for Peak Efficiency, by James Colotti, published in EDN 1979 October 5

- Notes on the Troubleshooting and Repair of Small Switchmode Power Supplies, by Samuel M. Goldwasser as part of Sci.Electronics.Repair FAQ