Tightlacing (also called corset training) is the practice of wearing an increasingly tightly laced corset to achieve cosmetic modifications to the figure and posture or to experience the sensation of bodily restriction. The process originates in mid-19th century Europe and was highly controversial. At the peak of the prevalence of tightlacing, there was much public backlash both from medical doctors and dress reformers, and it was often ridiculed as vain by the general public. Due to a combination of evolving fashion trends, social change regarding the roles of women, and material shortages brought on by World War I and II, tightlacing, and corsets in general, fell out of favor entirely by the early 20th century.

History

See also: History of corsets, Corset, and Corset controversyThe corset was a standard undergarment in Western dress for about 400 years beginning in the late 16th century and ending around the beginning of the 20th century. However, the practice of tightlacing began only in the late 1820s and 1830s, after the advent of the steel eyelet in 1827. The use of steel in both eyelets and boning allowed wearers to lace their corsets significantly tighter without damaging the garment.

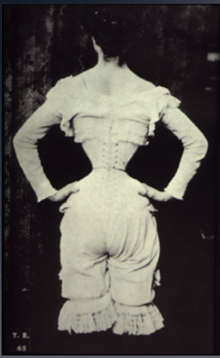

Additionally, corsets were among the first garments to be mass-manufactured via assembly line. This increased the accessibility of high-quality corsets and meant that middle- and lower-class women could purchase corsets where before they may have worn corded "jumps". Dress historian David Kunzle maintains that tightlacing was largely the domain of middle to lower middle class women hoping to increase their station in life; he estimates that the average corseted waist size of the 1880s was approximately 21 inches (53 cm), with an uncorseted waist size of about 27 inches (69 cm). Boarding schools for such young women incorporated corset training into their education, instructing students to sleep in corsets and achieve ever-smaller waistlines.

In the late years of the Victorian era, medical reports and rumors claimed that tightlacing was fatally detrimental to health (see Victorian dress reform). Women who suffered to achieve small waists were also condemned for their vanity and excoriated from the pulpit as slaves to fashion. Dress reformers exhorted women to abandon the tyranny of stays and free their waists for work and healthy exercise, with an emphasis on the negative consequences to one's reproductive system.

Despite the efforts of dress reformers to eliminate the corset, and despite medical and clerical warnings, women persisted in tightlacing, although a number of design changes were made to the standard corset which purported to alleviate its effects on the wearer's health. By the 1910s and 20s, the corset had begun to fall out of fashion entirely, driven by both cultural and practical changes. The need for steel during World War I and World War II made corsets a luxury rather than a necessity. At the same time, first-wave feminism, the Artistic Dress movement, and the flapper subculture popularized less exaggerated silhouettes, and elasticated girdles and brassieres began to rise in popularity to create a less rigidly shaped figure. Although the structured, corseted wasp-waist made a resurgence after World War II in the form of the New Look, there was soon backlash with hippie culture; meanwhile, the rise of popular fitness culture meant that diet, liposuction, and exercise became the preferred methods of achieving a thin waist. Corsets were no longer fashionable, but they entered the underworld of the fetish, along with items such as bondage gear and vinyl catsuits, as well as alternative and runway fashions, as seen in the work of Vivienne Westwood or in the goth subculture. They are often worn as top garments rather than underwear. Historical reenactors often wear corsets, but few tightlace.

Process

Achieving extremely small waist sizes requires a long period of training with ever-smaller corsets, ideally during one's pre-teen or teen years. A number of accounts of the corset training process take place under the regime of a finishing school, as achieving a very small waist was thought to make a woman appear refined and fashionable and thus increase the wearer's ability to attract a suitable husband.

Although there was no standardized system of corset training, some contemporary accounts give us an idea of what this training period was like. Corsets were begun at whatever age one's mother or female guardian felt was appropriate, which could be as young as seven or as old as 18 or 19.

Each of my own daughters – I have four – on her seventh birthday was provided with a snugly-fitting pair of corsets, which she wore from that time out, by night as well as by day, unless in case of decided illness. As the child grew, more bones were added, and the chest and hip measure was increased, but no alteration was made in the waist, and no expansion being allowed during the hours of sleep, its tenuity was retained and there was no necessity of resorting to tight-lacing, which becomes requisite where corsets are not worn until the figure has grown large.

— Letter to the editor, The Boston Globe

Corset makers themselves could also give a woman a regimen of increasingly smaller corsets:

In our business, we constantly find women who want to have the waist made smaller and who are willing to endure anything in the world except hanging to get a little waist. ... We measure the corset, pulling the measurements snug. And we tell the woman to wear it as tightly as she can comfortably do. Then we suggest a series of corsets, each a little smaller than the last, thus making the transition a slow and easy one from a big waist to a little one.

A common practice was to sleep with corsets still on, to prevent the waist from expanding again at night. To prevent girls from loosening or cutting the laces at night, different strategies were employed, such as using corporal punishment, tying an unusual knot that could not be replicated, fastening a padlock chain around the waist, or even, in one case, tying the child's hands behind her back. However, some felt this method cruel and unnecessary, recommending a looser corset for nighttime or foregoing the nighttime corset completely.

In 1895, The West Australian published an account purporting to be from the early 1860s, the diary of a student at an all-girls boarding school which described how their school madams trained girls to achieve waists ranging from 14 inches (36 cm) to 19 inches (48 cm) at a rate of a quarter-inch (.6 cm) per month. The narrator reports a reduction from 23 inches (58 cm) to 14 inches (36 cm), and a subsequent interview with a corsetmaking firm corroborated that such sizes were not unusual during that period.

Another account from a "fashionable school in London" fondly recalls the practice as a source of rivalry and pride among schoolgirls in her youth, reporting a reduction of about one inch per month, ultimately achieving a waist of 13 inches (33 cm) from her original 23 inches (58 cm).

Every morning one of the maids used to come to assist us to dress, and a governess superintended, to see that our corsets were drawn as tight as possible. After the first few minutes every morning I felt no pain, and the only ill effects apparently were occasional headaches and loss of appetite. Generally all the blame is laid by parents on the principal of the school, but it is often a subject of the greatest rivalry among the girls to see which can get the smallest waist, and often while servant was drawing in the waist of my friend to the utmost of her strength, the young lady, though being tightened till she had hardly breath to speak, would urge the maid to pull the stays yet closer, and tell her not to let the lace slip in the least.

Although most of these accounts describe adolescent girls, there are some sources which confirm that this process can take place at older ages, albeit with more difficulty. Many records of older women who tightlaced were induced to do so by their husbands, such as in the case of Ethel Granger, and had an element of sexual fetishism. The majority of people taking part in tightlacing were likely teenagers or young adults; the smallest waist sizes on record should be contextualized as such.

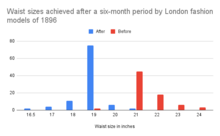

Tightlacing appears to have been a source of great pride and at times pleasure for many practitioners. However, there were also many who protested or were totally unable to achieve significant reductions. In 1896, a fashion house employee reported that, of the shop girls who undertook the training process to achieve the desired waist size of 19 inches (48 cm), "out of every 100 girls she found three could not lace at all, six laced with difficulty, eight eventually gave up, ten endured the bondage, seventy really enjoyed it, and three laced excessively." Dress historian David Kunzle theorized that some enthusiastic fans of tightlacing may have experienced sexual pleasure when tightlacing, or by rubbing against the front of the corset, which contributed to the moral outrage against the practice. Although such issues could not be discussed openly, many testimonials report feeling a pleasant numb or tingling sensation when tightlacing.

Criticism

The practice of tightlacing drew criticism from a wide variety of groups. The practice was widely ridiculed in satirical sources such as newspaper cartoons, which depicted the practice as frivolous, harmful, and unattractive.

American women active in the anti-slavery and temperance movements, with experience in public speaking and political agitation, advocated for and wore sensible clothing that would not restrict their movement, although corsets were a part of their wardrobe. While supporters of fashionable dress contended that corsets maintained an upright, "good figure", and were a necessary physical structure for a moral and well-ordered society, dress reformers maintained that women's fashions were not only physically detrimental, but "the results of male conspiracy to make women subservient by cultivating them in slave psychology". They believed a change in fashions could change the position of women in society, allowing for greater social mobility, independence from men and marriage, and the ability to work for wages, as well as physical movement and comfort.

Along with activists, many doctors spoke out against the practice. One Doctor Lewis writes in an 1882 edition of The North American Review:

A girl who has indulged in tight lacing should not marry. She may be a very devoted wife, yet her husband will secretly regret his marriage. Physicians of experience know what is meant, while thousands of husbands will not only know, but deeply feel the meaning of this hint.

This likely alluded to problems with the reproductive organs experienced by women who wore corsets, and demonstrates the difficulties of explaining this issue due to sexual taboos.

This pushback led to a number of developments in the design of the corset. Because of the public health outcry surrounding corsets and tightlacing, some doctors took it upon themselves to become corsetieres. Many doctors helped to fit their patients with corsets to avoid the dangers of ill-fitting corsets, and some doctors even designed corsets themselves. Roxey Ann Caplin became a widely renowned corset maker, enlisting the help of her husband, a physician, to create corsets which she purported to be more respectful of human anatomy. Health corsets and "rational corsets" became popular alternatives to the boned corset. They included features such as wool lining, watch springs as boning, elastic paneling, and other features purported to be less detrimental to one's health. The practice of training girls to tightlace at an early age seems to have completely fallen out of favor by the early 20th century, seen as a curiosity of a more foolish time.

Notable adherents

- Empress Elisabeth of Austria (Sisi); 16 inches (41 cm)

- Polaire; about 1914; 13–14 inches (33–36 cm)

- Cathie Jung; 2006; 15 inches (38 cm)

- Dita Von Teese; 16.5 inches (42 cm)

- Maud of Wales; queen of Norway; 18 inches (45 cm)

- Ethel Granger; 13 inches (33 cm)

See also

References

- ^ Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09953-3.

- ^ Summers, Leigh (2001). Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset (reprint ed.). Berg Publishers. ISBN 185973510X.

- ^ Kunzle, David (2006). Fashion and Fetishism: Corsets, tight lacing, and other forms of body sculpture. History Press. ISBN 0750938099.

- "The Inaccuracies of History's Most Fetishised Undergarment • T Australia". 14 July 2022.

- ^ Stevenson, NJ (2011). The Chronology of Fashion. London: The Ivy Press.

- ^ "Corsets and Such, A Devotee of the Corset" Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Boston Globe (8 January 1888)

- "Women Must All Tighten Up" Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Daily Tribune (29 December 1907)

- ^ "Wasp Waist Contests" Amador Ledger (21 July 1911)

- ^ "Figure Training at a Fashionable Boarding School". The West Australian. 2 November 1895. p. 10. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Waugh, Norah. Corsets and Crinolines New York: Theater Arts Books, 1954, p. 141

- ^ "Women's Kingdom" Toronto Daily Mail (7 April 1883) p. 5

- ^ "The Ladies Page Western Mail (12 June 1896)

- Kunzle, David (2006). Fashion and Fetishism: Corsets, tight lacing, and other forms of body sculpture. History Press. ISBN 0750938099.

- "The Proof of the Pudding" Toronto Daily Mail (5 May 1883) p. 5

- "Woman's dress, a question of the day". Early Canadiana Online. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986) p. 134

- Riegel, Robert E. (1963). "Women's Clothes and Women's Right". American Quarterly. 15 (3): 390–401. doi:10.2307/2711370. JSTOR 2711370.

- Riegel, Robert E. (1963). "Women's Clothes and Women's Right". American Quarterly. 15 (3): 391. doi:10.2307/2711370. JSTOR 2711370.

- The North American Review. University of Northern Iowa. 1882.

Further reading

- Le corset; étude physiologique et pratique

- Tight Lacing, Peter Farrer. ISBN 0-9512385-8-2

- The Corset and the Crinoline. A Book of Modes and Costumes from remote periods to the present time. Lord William Barry. (1869)

- Valerie Steele, The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-300-09953-3.

- David Kunzle, "Fashion and fetishism: a social history of the corset, tight-lacing, and other forms of body-sculpture in the West", Rowman and Littlefield, 1982, ISBN 0-8476-6276-4

- Bound To Please: A History of the Victorian Corset, Leigh Summers, Berg Publishers, 2001. ISBN 1-85973-510-X

| Corsets and corsetmaking | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of corset |  | |

| Corsetmaking | |||

| History | |||

| Corset fetishism | |||

| Corset manufacturers | |||

| Categories | |||

| Sexual fetishism | |

|---|---|

| Actions, states |

|

| Body parts | |

| Clothing | |

| Objects | |

| Controversial / illegal | |

| Culture / media | |

| Race | |

| Related topics | |