Roman infantry tactics are the theoretical and historical deployment, formation, and manoeuvres of the Roman infantry from the start of the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The original Roman army was made up of hoplites, whose main strategy was forming into a phalanx. By the early third century BCE, the Roman army would switch to the maniple system, which would divide the Roman army into three units, hastati, principes, and triarii. Later, in 107 BCE, Marius would institute the so-called Marian reforms, creating the Roman legions. This system would evolve into the Late Roman Army, which utilized the comitatenses and limitanei units to defend the Empire.

Roman legionaries had armour, a gladius, a shield, two pila, and food rations. They carried around tools such as a dolabra, a wooden stave, and a shallow wicker basket. These tools would be used for building castra (camps). Sometimes Roman soldiers would have mules that carried equipment. Legionaries carried onagers, ballistae, and scorpios.

Roman soldiers would train for four months. They learned marching skills first, followed by learning how to use their weapons. Then they began to spar with other soldiers. During the training exercise, the soldiers would also be taught to obey their commanders and either the Republic or the Emperor.

Legions were divided into units called cohorts. Each cohort was divided into three maniples. Each maniple was divided into centuries. Several legions made up field armies. During the Republic consuls, proconsuls, praetors, propraetors, and dictators were the only officials that could command an army. A legatus assisted the magistrate in commanding the legion.

While marching, the legion would deploy in several columns with a vanguard before them. This formation would be surrounded by soldiers on the flanks. Afterwards, the soldiers would construct a fortified camp. After staying in the camp for some time, the army would destroy the camp to prevent its use by the enemy, and then continue moving. The commanders of the Roman army might try to gather intelligence on the enemy. During the march, the commander would try to boost the morale of his soldiers.

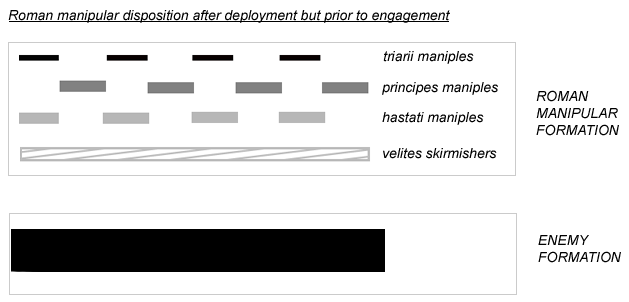

Before a battle, the commander would try to manoeuvre his army in a way that granted him the advantage. If the battle was fought when the maniple system was in place, the army would have the hastati in the front, the principes in the middle, and the triarii in the back. Skirmishers called velites would be placed in front of the army in order to throw javelins at the enemy. Once the so-called Marian reforms were enacted, the same formations and strategies continued to be used. However, instead of hastati, principes, and triarii they used cohorts.

When conducting a siege the army would begin by building a military camp. Then they would use siege weapons and the soldiers to assault the city and take it. When defending a city they built palisades, assault roads, moles, breakwaters, and double walls. The legions also would build a camp.

Evolution

Roman military tactics evolved from the type of a small tribal host-seeking local hegemony to massive operations encompassing a world empire. This advance was affected by changing trends in Roman political, social, and economic life, and that of the larger Mediterranean world, but it was also under-girded by a distinctive "Roman way" of war. This approach included a tendency towards standardization and systematization, practical borrowing, copying and adapting from outsiders, flexibility in tactics and methods, a strong sense of discipline, a ruthless persistence which sought comprehensive victory, and a cohesion brought about by the idea of Roman citizenship under arms – embodied in the legion. These elements waxed and waned over time, but they form a distinct basis underlying Rome's rise.

Some key phases of this evolution throughout Rome's military history include:

- The military was not a tactic of force, but rather a patience game.

- Military forces based primarily on citizen heavy infantry with tribal beginnings and early use of phalanx-type elements (see Military establishment of the Roman kingdom).

- Growing sophistication as Roman hegemony expanded outside of Italy and into North Africa, Western Europe, Greece, Anatolia, and South-west Asia (see Military establishment of the Roman Republic).

- Continued refinement, standardization, and streamlining in the period associated with Gaius Marius including broader-based incorporation of plebeian citizenry into the army, and more professionalism and permanence in army service.

- Continued expansion, flexibility, and sophistication from the end of the Republic into the time of the Caesars (see Military establishment of the Roman Empire).

- Growing barbarization, turmoil, and weakening of the heavy infantry units in favour of cavalry and lighter troops (see Foederati).

- Demise of the Western Empire and fragmentation into smaller, weaker local forces. This included the reversal of status of cavalry and infantry in the Eastern Empire. Cataphract forces formed an elite and became the Empire's primary shock troops, with infantry being reduced to auxiliaries fulfilling supporting functions.

Roman infantry of the Kingdom and Early Republic

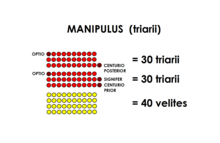

The earliest soldiers of the Roman army were hoplites. Census data from the Roman Kingdom shows the soldiers were hoplites who fought in a phalanx formation similar to how the Greek soldiers of this period fought. Cavalrymen went into battle with their torsos bare. The legion of the Early Roman Republic was divided into thirty sets of 120–160 men strong maniples organized into three lines of ten maniples. Generally positioned in front of the main infantrymen were skirmishers called velites. The velites would fight in a swarm of uncoordinated soldiers. Under standard practice, they had no direct commander as the other maniples had. The velites purpose on the battlefield was using javelins to disrupt the enemy formation and to inflict some preliminary casualties. The first structured unit line was made up of hastati, the second principes, and the third triarii. Each maniple was directly commanded by two centurions and the whole legion was commanded by six tribunes. Each maniple had a aeneator, who used acoustical signaling to convey orders between maniples.

The soldiers in the manipular legions would be heavily spaced apart, allowing greater flexibility on the battlefield. The maniple units were spaced twenty yards apart and a hundred yards from the next line of manipular soldiers. Aside from improving the flexibility of the legion, the space between each maniple unit meant that if a line was routed, they could retreat through the gaps. The next line could then attack the enemy. This manoeuvre could be repeated indefinitely so the enemy would always be facing fresh units of Romans. The maniples in the army could act totally independent of one another, giving commanders more situational discretion and allowing them to use the element of surprise to its maximum effect. Livy states that soldiers would "open" the maniple in order to let the soldiers fight well. It is unknown how the soldiers opened the maniple, but it was probably by ordering one soldier in every second line to take a step forward. This manoeuvre would result in soldiers having a checkerboard formation. Cassius Dio and other historians claimed that the maniples would expand laterally, as this movement would fill in the gaps in the formation and expand the space between each soldier. Such a manoeuvre may be feasible during a lull in the fighting during a battle, however, during the heat of battle, the manoeuvre would be difficult to manage and time-consuming.

Polybius described the swordsmanship of the Roman army as:

In their manner of fighting, however, each man undertakes movement on his own, protecting his body with his long shield, parrying a blow, and fighting hand to hand with the cut and thrust of his sword. They therefore clearly require space and flexibility between each other, so that each soldier must have three feet from the men to his flank and rear, if they are to be effective.

It is unclear whether Polybius meant the "three feet" counts the space occupied by the Roman soldier and his equipment. If Polybius meant this, then each Roman soldier would have nine feet between him and the other soldiers. It is also possible Polybius included the area the soldier occupied, which meant the soldier had six feet of space between them and the other soldiers. Vegetius talked about Roman soldiers having three feet between them. Depictions of Roman soldiers in art suggest that the gap between soldiers is 65–75 centimetres (25-30 inches). Modern scholars such as Michael J Taylor state that the gaps between the maniples were 10–20 meters (33 to 66 feet).

Roman infantry of the Late Republic and Early Empire

The legions after the so-called Marian reforms were able to form into a close-defensive formation to resist a barrage of arrow fire or an enemy charge. This formation was called testudo. The Roman legionary cohorts continued to use the testudo formation throughout the remainder of their history until the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. When in battle, the legions would be separated into their respective cohorts. Four of the cohorts would line up on the battle line and lead. The other six would follow behind the first four as reserves should many men fall in battle. If Roman cavalry were involved, they were placed on the sides of the main cohorts. Like the Early Republican armies, the legion cohorts were still organized into the same checkerboard formation. The soldiers marched forward until they met the enemy and proceeded to attack. The initial formation of soldiers was dictated by the enemy's formation, the terrain of the battlefield, and the types of troops which the legion in question was composed of. In order to soften up the enemy before the main infantry, the soldiers threw pila; additionally, they shot arrows if they had archers among them. On occasion, a legion would use ballistae, or pieces of field artillery which threw large arrow-like projectiles which served to inflict casualties, frighten enemies, and disrupt their formations. To instil fear into their enemy, the soldiers of a legion would march onto an enemy completely silent until they were close enough to attack. At that point, the entire army would utter a battle cry to frighten their enemy. When their tactics did not initially work, commanders would often mould their tactics to what was necessary.

Roman infantry of the Late Empire

The army of the Late Roman Empire consisted of the limitanei and comitatenses armies. The Germanic tribes contributed paramilitary units called foederati to the Roman army. The limitanei defended the borders of the Empire from small attacks and raids by the Germanic peoples. They would also hold the frontier against a larger invasion long enough for the comitatenses legions to arrive. The limitanei would be stationed in their own forts throughout the Empire. Usually, these forts were in or near cities and villages. This meant that the soldiers were in constant interaction with civilians. Often, the soldiers' families would live in the cities or villages near the fort. Occasionally, villages and towns would grow around these forts in order to suit the needs of the limitanei.

This strategy has been described as defence in depth. The comitatenses were grouped into field armies. The Emperor would have his own personal comitatenses army to help fight rebellions. Roman generals of the late Empire would try to avoid pitched battles in order to conserve manpower. During a battle, the comitatenses legions would wait in a defensive formation while performing a shield wall. The Romans would then try to use their superior coordination to repulse the enemy attack. Skirmishers would be placed in front of the Roman line in order to inflict casualties on the enemy and reduce the amount of comitatenses killed in battle. After Attila's invasion of the Roman Empire, the Romans started to use mounted archers.

Manpower

Numerous scholarly histories of the Roman military machine note the huge numbers of men that could be mobilized, more than any other Mediterranean power during the period. This bounty of military resources enabled Rome to apply crushing pressure to its enemies and stay in the field and replace losses, even after suffering setbacks. One historian of the Second Punic War states:

According to Polybius (2.24), the total number of Roman and allied men capable of bearing arms in 225 BC exceeded 700,000 infantry and 70,000 cavalries. Brunt adjusted Polybius’ figures and estimated that the population of Italy, not including Greeks and Bruttians, exceeded 875,000 free adult males, from whom the Romans could levy troops. Rome not only had the potential to levy vast numbers of troops but did in fact field large armies in the opening stages of a war. Brunt estimates Rome mobilized 108,000 men for service in the legions between 218 BC and 215 BC, while at the height of the war effort (214 BC to 212 BC) Rome was able to mobilize approximately 230,000 men. Against these mighty resources, Hannibal led from Spain an army of approximately 50,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry ... Rome's manpower reserves allowed it to absorb staggering losses, yet still continue to field large armies. For example, according to Brunt, as many as 50,000 men were lost between 218 BC and 215 BC, but Rome continued to place between 14 and 25 legions in the field for the duration of the war. Moreover, as will be discussed below, Roman manpower allowed for the adoption of the so-called "Fabian strategy", which proved to be an effective response to Hannibal's apparent battlefield superiority. Put simply, the relative disparity in the number of available troops at the outset of the conflict meant that Hannibal had a much narrower margin for error than the Romans.

Equipment and training

Further information: Roman military personal equipment and Roman legionEquipment

Individual weapons, personal equipment and haulage

A legionary typically carried around 27 kilograms (60 pounds) of armour, weapons, and equipment. This load consisted of armour, a sword called gladius, a shield, two pila (one heavy, one light), and five days' food rations. There were also tools for digging and constructing a castrum, the legions' fortified base camp. One writer recreates the following as to Caesar's army in Gaul: Each soldier arranged his heavy pack on a T- or Y-shaped rod (furca), borne on his left shoulder. Shields were protected on the march with a hide cover. Each legionary carried about five days' worth of wheat, pulses or chickpeas, a flask of oil, and a mess kit with a dish, cup, and utensil. Personal items might include a dyed horsehair crest for the helmet, a semi-water-resistant oiled woollen cloak, socks and breeches for cold weather and a blanket. Entrenchment equipment included a shallow wicker basket for moving earth, a spade and/or pick-axe like dolabra or turf cutter, and two wooden staves to construct the next camp palisade. All these were arranged in the marching pack toted by each infantryman.

Fighters travelled in groups of eight, and each octet was sometimes assigned a mule. The mule carried a variety of equipment and supplies, e.g. a mill for grinding grain, a small clay oven for baking bread, cooking pots, spare weapons, waterskins, and tents. A Roman centuria had a complement of ten mules, each attended by two non-combatants who handled foraging and water supply. It might be supported by wagons in the rear, each drawn by six mules and carrying tools, nails, water barrels, extra food and the tent and possessions of the centurion (commanding officer of the unit).

Artillery package

The legion also carried an artillery detachment with thirty pieces of artillery. This consisted of ten stone-throwing onagers and twenty bolt-shooting ballistas; in addition, each of the legion's centuries had its own scorpio bolt thrower (sixty total), together with supporting wagons to carry ammunition and spare parts. Bolts were used for targeted fire on human opponents, while stones were used against fortifications or as an area saturation weapon. The catapults were powered by rope and sinew, tightened by a ratchet and released, powered by the stored torsion energy. Caesar was to mount these in boats on some operations in Britain, striking fear in the heart of the native opponents according to his writings. His placement of siege engines and bolt throwers in the towers and along the wall of his enclosing fortifications at Alesia was critical to turning back the enormous tide of Gauls. These defensive measures, used in concert with the cavalry charge led by Caesar himself, broke the Gauls and won the battle – and therefore the war – for good. Bolt-throwers like the scorpio were mobile and could be deployed in defence of camps, field entrenchments and even in the open field by no more than two or three men.

Training

According to Vegetius, during the four-month initial training of a Roman legionary, marching skills were taught before recruits ever handled a weapon, since any formation would be split up by stragglers at the back or soldiers trundling along at differing speeds. Standards varied over time, but normally recruits were first required to complete 20 Roman miles (29.62 km or 18.405 modern miles) with 20.5 kg in five summer hours (the Roman day was divided into 12 hours regardless of season, as was the night), which was known as "the regular step" or "military pace". They then progressed to the "faster step" or "full pace" and were required to complete 24 Roman miles (35.544 km or 22.086 modern miles) in five summer hours loaded with 20.5 kilograms (45 lb). The typical conditioning regime also included gymnastics and swimming to build physical strength and fitness.

After conditioning, the recruits underwent weapons training; this was deemed of such importance that weapons instructors generally received double rations. Legionaries were trained to thrust with their gladii because they could defend themselves behind their large shields (scuta) while stabbing the enemy. These training exercises began with thrusting a wooden gladius and throwing wooden pila into a quintain (wooden dummy or stake) while wearing full armour. Their wooden swords and pila were designed to be twice as heavy as their metal counterparts so that the soldiers could wield a true gladius with ease. Next, soldiers progressed to armatura, a term for sparring that was also used to describe the similar one-on-one training of gladiators. Unlike earlier training, the wooden weapons used for armatura were the same weight as the weapons they emulated. Vegetius notes that roofed halls were built to allow for these drills to continue throughout the winter.

Other training exercises taught the legionary to obey commands and assume battle formations. At the end of training the legionary had to swear an oath of loyalty to the SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus, the Senate and the Roman people) or later to the emperor. The soldier was then given a military diploma and sent off to fight for his living and the glory and honour of Rome.

Organization, leadership and logistics

Command, control and structure

Once the soldier had finished his training, he was typically assigned to a legion, the basic mass fighting force. The legion was split into ten sub-units called cohorts, roughly comparable to a modern infantry battalion. The cohorts were further sub-divided into three maniples, which in turn were split into two centuriae of about eighty men each. The first cohort in a legion was usually the strongest, with the fullest personnel complement and with the most skilled, experienced men. Several legions grouped together made up a distinctive field force or "army". Fighting strength could vary, but generally a legion was made up of 4,800 soldiers, 60 centurions, 300 artillerymen, 100 engineers and artificers, and 1,200 non-combatants. Each legion was supported by a unit of 300 cavalries, the equites.

Supreme command of either legion or army was by consul or proconsul or a praetor, or in cases of emergency in the republican era, a dictator. A praetor or a propraetor could only command a single legion and not a consular army, which normally consisted of two legions plus the allies. In the early republican period, it was customary for an army to have dual commands, with different consuls holding the office on alternate days. In later centuries, this was phased out in favour of one overall army commander. The legati were officers of senatorial rank who assisted the supreme commander. Tribunes were young men of aristocratic rank who often supervised administrative tasks such as camp construction. Centurions (roughly equivalent in rank to today's non-commissioned or junior officers, but functioning as modern captains in field operations) commanded cohorts, maniples and centuries. Specialist groups like engineers and artificers were also used.

Military structure and ranks

For an in-depth analysis of ranks, types, and historical units, see Structural history of the Roman military and Roman legion for a detailed breakdown. Below is a very basic summary of the legion's structure and ranks.

Force structure

- Contubernium: "tent unit" of eight men.

- Centuria: 80 men commanded by a centurion.

- Cohort: six centuries or a total of 480 fighting men. Added to these were officers. The first cohort was double strength in terms of manpower and generally held the best fighting men.

- Legion: made up of ten cohorts.

- Field army: a grouping of several legions and auxiliary cohorts.

- Equites: Each legion was supported by 300 cavalry (equites), sub-divided into ten turmae.

- Auxilia and velites: allied contingents, often providing light infantry and specialist fighting services, like archers, slingers or javelin-men. They were usually formed into the light infantry or velites. Auxilia in the republican period also formed allied heavy legions to complement Roman citizen formations.

- Non-combatant support: generally the men who tended the mules, forage, watering and sundries of the baggage train.

- 4,500–5,200 men in a legion.

Rank summary

- Consul – an elected official with military and civic duties; like a co-president (there were two), but also a major military commander.

- Praetor – appointed military commander of a legion or grouping of legions, also a government official.

- Legatus – the legate or overall legion commander, usually filled by a senator.

- Tribune – young officer, second in command of the legion. Other lesser tribunes served as junior officers.

- Praefectus – third in command of the legion. There were various types. The prefectus equitarius commanded a unit of cavalry.

- Primus pilus – commanding centurion for the first cohort – the senior centurion of the entire legion.

- Centurion – basic commander of the century. Prestige varied based on the cohort they supervised.

- Decurion – commander of a turma (cavalry unit).

- Optio – equivalent to a sergeant, second in command for the centurion.

- Decanus – equivalent to a corporal, commanded about eight.

- Munifex – basic (but well trained) soldier.

- Tirones – new recruit, a novice.

Logistics

Roman logistics were among some of the best in the ancient world over the centuries, from the deployment of purchasing agents to systematically buy provisions during a campaign, to the construction of roads and supply caches, to the rental of shipping if the troops had to move by water. Heavy equipment and material (tents, artillery, extra weapons and equipment, millstones, etc.) were moved by pack animal and cart, while troops carried weighty individual packs with them, including staves and shovels for constructing the fortified camps. Typical of all armies, local opportunities were also exploited by troops on the spot, and the fields of peasant farmers who were near the zone of conflict might be stripped to meet army needs. As with most armed forces, a variety of traders, hucksters, prostitutes, and other miscellaneous service providers trailed in the wake of the Roman fighting men.

Battle

Initial preparations and movement for battle

The approach march. Once the legion was deployed on an operation, the marching began. The approach to the battlefield was made in several columns, enhancing manoeuvrability. Typically, a strong vanguard preceded the main body and included scouts, cavalry, and light troops. A tribune or other officer often accompanied the vanguard to survey the terrain for possible camp locations. Flank and reconnaissance elements were also deployed to provide the usual covering security. Behind the vanguard came the main body of heavy infantry. Each legion marched as a distinct formation and was accompanied by its own individual baggage train. The last legion usually provided the rear force, although several recently raised units might occupy this final echelon.

Construction of fortified camps. Legions on a campaign typically established a strong field camp, complete with palisade and a deep ditch, providing a basis for supply storage, troop marshalling, and defense. Camps were recreated each time the army moved and were constructed with a view to both military necessity and religious symbolism. There were always four gateways, connected by two main crisscrossing streets, with the intersection at a concentration of command tents in the centre. Space was also made for an altar and religious gathering area. Everything was standardized, from the positioning of baggage, equipment and specific army units, to the duties of officers who were to set up sentries, pickets, and orders for the next day's march. Construction could take between two and five hours with part of the army labouring, while the rest stood guard, depending on the tactical situation and operating environment. The shape of the camp was generally rectangular but could vary based on the terrain or tactical situation. A distance of about 60 meters (197 feet) was left clear between the entrenchments and the first row of troop tents. This gap provided space for marshalling the legionaries for battle and kept the troop area out of enemy missile range. No other ancient army persisted over such a long period in systematic camp construction like the Romans, even if the army rested for only a single day.

Breaking camp and marching. After a regimented breakfast at the allocated time, trumpets were sounded and the camp's tents and huts were dismantled and preparations made for departure. The trumpet then sounded again with the signal for "stand by to march". Mules and wagons of the baggage train were loaded and units formed up. The camp was then burned to the ground to prevent its later occupation and use by the enemy. The trumpets would then be sounded for a final time after which the troops were asked three times whether they were ready, to which they were expected to shout together "Ready!" before marching off.

Intelligence. Good Roman commanders did not hesitate to exploit useful intelligence, particularly where a siege situation or an impending clash in the field was developing. Information was gathered from spies, collaborators, diplomats and envoys, and allies. Intercepted messages during the Second Punic War for example were an intelligence coup for the Romans, and enabled them to dispatch two armies to find and destroy Hasdrubal's Carthaginian force, preventing his reinforcement of Hannibal. Commanders also kept an eye on the situation in Rome since political enemies and rivals could use an unsuccessful campaign to inflict painful career and personal damage. During this initial phase, the usual field reconnaissance was also conducted – patrols might be sent out, raids mounted to probe for weaknesses, prisoners snatched, and local inhabitants intimidated.

Morale. If the field of potential battle was near, the movement became more careful and more tentative. Several days might be spent in a location studying the terrain and opposition, while the troops were prepared mentally and physically for battle. Pep talks, sacrifices to the gods, and the announcements of good omens might be carried out. A number of practical demonstrations might also be undertaken to test enemy reaction as well as to build troop morale. Part of the army might be led out of the camp and drawn up in battle array towards the enemy. If the enemy refused to come out and at least make a demonstration, the commander could claim a morale advantage for his men, contrasting the timidity of the opposition with the resolution of his fighting forces.

Historian Adrian Goldsworthy notes that such tentative pre-battle manoeuvring was typical of ancient armies as each side sought to gain the maximum advantage before the encounter. During this period, some ancient writers paint a picture of meetings between opposing commanders for negotiation or general discussion, as with the famous pre-clash conversation between Hannibal and Scipio at Zama. It is unknown if the recorded flowery speeches are non-fiction or embellishments by ancient historians, but these encounters do not show a record of resolving the conflict by means other than the anticipated battle.

Deployment for combat

Pre-battle manoeuvre gave the competing commanders a feel for the impending clash, but final outcomes could be unpredictable, even after the start of hostilities. Skirmishing could get out of hand, launching both main forces towards one another. Political considerations, exhaustion of supplies, or even rivalry between commanders for glory could also spark a forward launch, as at the Battle of the Trebia. The Roman army after the so-called Marian reforms was also unique in the ancient world because when lined up opposite an enemy readying for battle it was completely silent except for the orders of officers and the sound of trumpets signalling orders. The reason for this was because the soldiers needed to be able to hear such instruction. The optios of the legions would patrol behind the century and anyone who was talking or failing to obey orders immediately was struck with the stick of the optio. This silence also had the unintended consequence of being very intimidating to its enemies because they recognized this took immense discipline to achieve before a battle.

Layout of the triple line

Once the machinery was in motion, however, the Roman infantry typically was deployed as the main body, facing the enemy. During deployment in the republican era, the maniples were commonly arranged in triplex acies (triple battle order), that is, in three ranks, with the hastati in the first rank (that nearest the enemy), the principes in the second rank, and the veteran triarii in the third and final rank as barrier troops, or sometimes even further back as a strategic reserve. When in danger of imminent defeat, the first and second lines, the hastati and principes, ordinarily fell back on the triarii to reform the line to allow for either a counter-attack or an orderly withdrawal. Because falling back on the triarii was an act of desperation, to mention "returning to the triarii" (ad triarios redisse) became a common Roman phrase indicating one to be in a desperate situation.

Within this triplex acies system, contemporary Roman writers talk of the maniples adopting a checkered formation called quincunx when deployed for battle but not yet engaged. In the first line, the hastati left modest gaps between each maniple. The second line consisting of principes followed in a similar manner, lining up behind the gaps left by the first line. This was also done by the third line, standing behind the gaps in the second line. The velites were deployed in front of this line in a continuous, loose-formation line.

The manoeuvre of the Roman army was a complex one, filled with the dust of thousands of soldiers wheeling into place, and the shouting of officers moving to and from as they endeavoured to maintain order. Several thousand men had to be positioned from column into line, with each unit taking its designated place, along with light troops and cavalry. The fortified camps were laid out and organized to facilitate deployment. It often took some time for the final array of the host, but when accomplished the army's grouping of legions represented a formidable fighting force, typically arranged in three lines with a frontage as long as one mile (about 1.5 km).

A general three-line deployment was to remain over the centuries, although the so-called Marian reforms phased out most divisions based on age and class, standardized weapons, and reorganized the legions into larger manoeuvre units like cohorts. The overall size of the legion and length of the soldier's service also increased on a more permanent basis.

Maneuvering

As the army approached its enemy, the velites in front threw their javelins at the enemy and then retreat through the gaps in the lines. This was an important innovation since in other armies of the period skirmishers would have to either retreat through their own army's ranks, causing confusion or else to flee around either flank of their own army. After the velites had retreated through the hastati, the 'posterior' century marched to the left and then forward, creating a solid line of soldiers. The same procedure would be employed as they passed through the second and third ranks or turned to the side to channel down the gap between the first and second rows on route to help guard the legion's flanks.

At this point, the legion then presented a solid line to the enemy and the legion was in the correct formation for engagement. When the enemy closed, the hastati would charge. If they were losing the fight, the 'posterior' century returned to its position creating gaps again. Then the maniples fell back through the gaps in the principes, who followed the same procedure to form a battle line and charge. If the principes could not break the enemy, they would retreat behind the triarii and the whole army would leave the battlefield in good order. According to some writers, the triarii formed a continuous line when they deployed, and their forward movement allowed scattered or discomfited units to rest and reform, to later rejoin the struggle.

The manipular system allowed engaging every kind of enemy, even in rough terrain, because the legion had both flexibility and toughness according to the deployment of its lines. Lack of a strong cavalry corps, however, was a major tactical vulnerability of the Roman forces.

In the later Imperial Roman army, the general deployment was very similar, with the cohorts deploying in quincunx pattern. In a reflection of the earlier placement of the veteran triarii in the rear, the less experienced cohorts (usually the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 8th) were in the front; the more experienced cohorts (1st, 5th, 7th, 9th, and 10th) were placed behind.

Formations

The above is only standard procedure and was often modified as necessitated by varying circumstances; for example, at Zama, Scipio deployed his entire legion in a single line to envelop Hannibal's army just as Hannibal had done at the Battle of Cannae. A brief summary of alternative formations known to have been used is shown below:

Combat

Once the deployment and initial skirmishing described above took place, the main body of heavy infantry closed the gap and attacked the double. The front ranks usually cast their pila, and the following ranks hurled theirs over the heads of the front-line fighters. After the pila were cast, the soldiers then drew their swords and engaged the enemy. Emphasis was on using the shield to provide maximum body coverage, and for pushing enemies, while attacking with their gladius in thrusts and short cuts in clinch, minimizing exposure to the enemy. In the combat that ensued, Roman discipline, heavy shield, armour, and training were to give them important advantages in combat.

Some scholars of the Roman infantry maintain that the intense physical trauma and stress of hand-to-hand combat meant that the contenders did not simply hack at one another continuously until one dropped. Instead, there were short periods of intense, vicious fighting. If indecisive, the contenders might fall back a short distance to recuperate, and then surge forward to renew the struggle. Others behind them would be stepping up into the fray meanwhile, engaging new foes or covering their colleagues. The individual warrior could thus count on temporary relief, rather than endless fighting until death or crippling injury. As the battle progressed, the massive physical and mental stress intensified. The stamina and willpower demanded to make yet one more charge, to make yet one more surge, grew even greater. Eventually one side began to break down and it is then that the greatest slaughter began.

Many Roman battles, especially during the late Empire, were fought with the preparatory fire from catapults, ballistas and onagers. These war machines, a form of ancient artillery, fired arrows and large stones towards the enemy (although many historians question the battlefield effectiveness of such weapons). Following this barrage, the Roman infantry advanced in four lines, until they came within 30 meters (98 feet) of the enemy, then they halted, hurled their pila and charged. If the first line was repelled by the enemy, another line would rapidly resume the attack. Oftentimes, this rapid sequence of deadly attacks proved to be the key to victory. Another common tactic was to taunt the enemy with feigned charges and rapid arrow fire by the auxiliares equites (auxiliary cavalry), forcing the enemy into pursuing them, and then leading the enemy into an ambush where they would be counter-attacked by Roman heavy infantry and cavalry.

Three-line system advantages

Flexibility

Some ancient sources such as Polybius seem to imply that the legions could fight with gaps in their lines. Yet, most sources seem to admit that more usually a line would form into a solid front. Various approaches have been taken to reconcile these possibilities with the ancient writings. The advantages of gaps are obvious when a formation is on the move – it can more easily flow around obstacles and manoeuvre and control are enhanced and, as the Romans did in the pre-Marius Republic, place baggage between the lines meaning that the cargo cannot be easily captured and that the army can quickly get ready for a battle by using it as cover. After the approach marching was complete, it was extremely difficult to deploy an unbroken army of men for combat across any but the flattest ground without some sort of intervals. Many ancient armies used gaps of some sort, even the Carthaginians, who typically withdrew their initial skirmishing troops between the spaces before the main event. Even more loosely organized enemies such as the Germanic hosts typically charged in distinct groups with small gaps between them, rather than marching up in a neat line.

Fighting with gaps is thus tactically feasible, lending credibility to writers like Polybius, who assert they were used. According to those who support the quincunx formation view, what made the Roman approach stand out is that their intervals were generally larger and more systematically organized than those of other ancient armies. Each gap was covered by maniples or cohorts from lines farther back. Penetration of any significance could not just slip in unmolested. It would not only be mauled as it fought past the gauntlet of the first line, but would also clash with aggressive units moving up to plug the space. From a larger standpoint, as the battle waxed and waned, fresh units might be deployed through the intervals to relieve the men of the first line, allowing continual pressure to be brought forward.

Mixing of a continuous front with interval fighting

One scenario for not using gaps is deployment in a limited space, such as the top of a hill or in a ravine, where extensive spreading out would not be feasible. Another is a particular attack formation, such as the wedge discussed above, or an encirclement as at the Battle of Ilipa. Yet another is a closing phase manoeuvre when a solid line is constructed to make a last, final push as in the Battle of Zama. During the maelstrom of battle, it is also possible that as the units merged into line, the general checkerboard spacing became more compressed or even disappeared, and the fighting would see a more or less solid line engaged with the enemy. Thus, gaps at the beginning of the struggle might tend to vanish in the closing phases.

Some historians view the intervals as primarily useful in manoeuvre. Before the legionaries closed with the enemy, each echelon would form a solid line to engage. If things went badly for the first line, it would retreat through the gaps and the second echelon moved up, again forming a continuous front. Should they be discomfited, there still remained the veterans of the triarii, who let the survivors retreat through the preset gaps. The veterans then formed a continuous front to engage the enemy or provided cover for the retreat of the army as a whole. The same procedure was followed when the triarii was phased out – intervals for manoeuvre, reforming and recovery – solid line to engage. Some writers maintain that in Caesar's armies the use of the quincunx and its gaps seems to have declined, and his legions generally deployed in three unbroken lines as shown above, with four cohorts in front, and three apiece in the echeloned order. The relief was provided by the second and third lines 'filtering' forward to relieve their comrades in small groups, while the exhausted and wounded eased back from the front. The Romans still remained flexible however, using gaps and deploying four or sometimes two lines based on the tactical situation.

Line spacing and combat stamina

Another unique feature of the Roman infantry was the depth of its spacing. Most ancient armies deployed in shallower formations which might deepen their ranks heavily to add both stamina and shock power, but their general approach still favoured one massive line, as opposed to the deep Roman arrangement. The advantage of the Roman system is that it allowed the continual funnelling or metering of combat power forward over a longer period – massive, steadily renewed pressure to the front – until the enemy broke. Deployment of the second and third lines required careful consideration by the Roman commander. Deployed too early, they might get entangled in the frontal fighting and become exhausted. Deployed too late, they might be swept away in a rout if the first line began to break. Tight control had to be maintained, hence the third line triarii were sometimes made to squat or kneel, effectively discouraging premature movement to the front. The Roman commander was thus generally mobile, constantly moving from spot to spot, and often riding back in person to fetch reserves if there was no time for standard messenger service. A large number of officers in the typical Roman army, and the flexible breakdown into sub-units like cohorts or maniples, greatly aided in providing coordination for such moves.

Whatever structure the actual formation took, however, the ominous funnelling or surge of combat power up to the front remained constant:

- When the first line as a whole had done its best and become weakened and exhausted by losses, it gave way to the relief of freshmen from the second line who, passing through it gradually, pressed forward one by one, or in single file, and worked their way into the fight in the same way. Meanwhile, the tired men of the original first line, when sufficiently rested, reformed and re-entered the fight. This continued until all men of the first and second lines had been engaged. This does not presuppose an actual withdrawal of the first line, but rather a merging, a blending or a coalescing of both lines. Thus, the enemy was given no rest and was continually opposed by fresh troops until, exhausted and demoralized, yielded to repeated attacks.

Post-deployment commands

Whatever the deployment, the Roman army was marked by flexibility, strong discipline, and cohesion. Different formations were assumed according to different tactical situations.

- Repellere equites ("repel horsemen/knights") was the formation used to resist cavalry. The legionaries would assume a square formation, holding their pila as spears in the space between their shields and strung together shoulder to shoulder.

- At the command iacite pila, the legionaries hurled their pila at the enemy.

- At the command cuneum formate, the infantry formed a wedge to charge and break enemy lines. This formation was used as a shock tactic.

- At the command contendite vestra sponte, the legionaries assumed an aggressive stance and attacked every opponent they faced.

- At the command orbem formate, the legionaries assumed a circle-like formation with the archers placed in the midst of and behind the legionaries providing missile fire support. This tactic was used mainly when a small number of legionaries had to hold a position and were surrounded by enemies.

- At the command ciringite frontem, the legionaries held their position.

- At the command frontem allargate, a scattered formation was adopted.

- At the command testudinem formate, the legionaries assumed the testudo formation. This was slow-moving, but almost impenetrable to enemy fire, and thus very effective during sieges and/or when facing off against enemy archers. However, the testudo formation did not allow for effective close combat – therefore it was used only when the enemy were far enough away.

- At the command tecombre, the legionaries would break the testudo formation and revert to their previous formation.

- At the command Agmen formate, the legionaries assumed a square formation, which was also the typical shape of a century in battle.

Siegecraft and fortifications

Main article: Siege (Roman history)Besieging cities

Oppidum expugnare was the Roman term for besieging cities. It was divided into three phases:

- In the first phase, engineers (the cohors fabrorum) built a line of fortifications with walls of circumvallation and at the command turres extruere built watch towers to prevent the enemy from bringing in reinforcements. Siege towers were built, trenches were dug and traps set all around the city. A second, exterior line (contravallation) was built facing the enemy, as Caesar did at the Battle of Alesia. Sometimes the Romans would mine the enemy's walls.

- The second phase began with onager and ballista fire to cover the approach of the siege towers, which were full of legionaries ready to assault the wall's defenders. Meanwhile, other cohorts approached the city's wall in testudo formation, bringing up battering rams and ladders to breach the gates and scale the walls.

- The third phase included the opening of the city's main gate by the cohorts which had managed to break through or scale the walls, provided the rams had not knocked the gate open. Once the main gate was opened or the walls breached, the cavalry and other cohorts entered the city to finish off the remaining defenders.

Field fortifications

While strong cities/forts and elaborate sieges to capture them were common throughout the ancient world, the Romans were unique among ancient armies in their extensive use of field fortifications. In campaign after campaign, enormous effort was expended to dig – a job done by the ordinary legionary. His field pack included a shovel, a dolabra or pickaxe, and a wicker basket for hauling dirt. Some soldiers also carried a type of turf cutter. With these, they dug trenches, built walls and palisades and constructed assault roads. The operations of Julius Caesar at Alesia are well known. The Gallic city was surrounded by massive double walls penning in defenders, and keeping out relieving attackers. A network of camps and forts was included in these works. The inner trench alone was 20 feet (6.1 m) deep, and Caesar diverted a river to fill it with water. The ground was also sown with caltrops of iron barbs at various places to discourage assault. Surprisingly for such an infantry centred battle, Caesar relied heavily on cavalry forces to counter Gallic sorties. Ironically, many of these were from Germanic tribes who had come to terms earlier.

The power of Roman field camps has been noted earlier, but in other actions, the Romans sometimes used trenches to secure their flanks against envelopment when they were outnumbered, as Caesar did during operations in Belgaic Gaul. In the Brittany region of France, moles and breakwaters were constructed at enormous effort to assault the estuarine strongholds of the Gauls. Internal Roman fighting between Caesar and Pompey also saw the frequent employment of trenches, counter-trenches, dug-in strong points, and other works as the contenders manoeuvred against each other in field combat. In the latter stages of the empire, the extensive use of such field fortifications declined as the heavy infantry itself was phased down. Nevertheless, they were an integral part of the relentless Roman rise to dominance over large parts of the ancient world.

Infantry effectiveness

Roman infantry versus the Macedonian phalanx

Prior to the rise of Rome, the Macedonian phalanx was the premier infantry force in the Western World. It had proven itself on the battlefields of Mediterranean Europe, from Sparta to Macedonia, and had met and overcome several strong non-European armies from Persia to Northwest India. Packed into a dense armoured mass, and equipped with massive pikes 12 to 21 feet (6.4 m) in length, the phalanx was a formidable force. While defensive configurations were sometimes used, the phalanx was most effective when it was moving forward in attack, either in a frontal charge or in "oblique" or echeloned order against an opposing flank, as the victories of Alexander the Great and Theban innovator Epaminondas attest. When working with other formations (light infantry and cavalry) it was, at its height under Alexander, without peer.

Nevertheless, the Macedonian phalanx had key weaknesses. It had some manoeuvrability, but once a clash was joined this decreased, particularly on rough ground. Its "dense pack" approach also made it rigid. Compressed in the heat of battle, its troops could only primarily fight facing forward. The diversity of troops gave the phalanx great flexibility, but this diversity was a double-edged sword, relying on a mix of units that was complicated to control and position. These included not only the usual heavy infantrymen, cavalry and light infantry but also various elite units, medium armed groups, foreign contingents with their own styles and shock units of war-elephants. Such "mixed" forces presented additional command and control problems. If properly organized and fighting together a long time under capable leaders, they could be very proficient. The campaigns of Alexander and Pyrrhus (a Hellenic-style formation of mixed contingents) show this. Without such long-term cohesion and leadership, however, their performance was uneven. By the time the Romans were engaging against Hellenistic armies, the Greeks had ceased to use strong flank guards and cavalry contingents, and their system had degenerated into a mere clash of phalanxes. This was the formation overcome by the Romans at the Battle of Cynoscephalae.

The Romans themselves had retained some aspects of the classical phalanx (not to be confused with the Macedonian phalanx) in their early legions, most notably the final line of fighters in the classic "triple line", the spearmen of the triarii. The long pikes of the triarii were to eventually disappear, and all hands were uniformly equipped with short sword, shield and pilum, and deployed in the distinctive Roman tactical system, which provided more standardization and cohesion in the long run over the Hellenic type formations.

Phalanxes facing the legion were vulnerable to the more flexible Roman "checkerboard" deployment, which provided each fighting man a good chunk of personal space to engage in close order fighting. The manipular system also allowed entire Roman sub-units to manoeuvre more widely, freed from the need to always remain tightly packed in rigid formation. The deep three-line deployment of the Romans allowed combat pressure to be steadily applied forward. Most phalanxes favoured one huge line several ranks deep. This might do well in the initial stages, but as the battle entangled more and more men, the stacked Roman formation allowed fresh pressure to be imposed over a more extended time. As combat lengthened and the battlefield compressed, the phalanx might thus become exhausted or rendered immobile, while the Romans still had enough left to not only manoeuvre but to make the final surges forward. Hannibal's deployment at Zama appears to recognize this – hence the Carthaginian also used a deep three-layer approach, sacrificing his first two lower quality lines and holding back his combat-hardened veterans of Italy for the final encounter. Hannibal's arrangement had much to recommend it given his weakness in cavalry and infantry, but he made no provision for one line relieving the other as the Romans did. Each line fought its own lonely battle and the last ultimately perished when the Romans reorganized for a final surge.

The legions also drilled and trained together over a more extended time, and were more uniform and streamlined, (unlike Hannibal's final force and others) enabling even less than brilliant army commanders to manoeuvre and position their forces proficiently. These qualities, among others, made them more than a match for the phalanx, when they met in combat.

According to Polybius, in his comparison of the phalanx versus the Roman system:

- ... Whereas the phalanx requires one time and one type of ground. Its use requires flat and level ground which is unencumbered by any obstacles ... If the enemy refuses to come down to ... what purpose can the phalanx serve? ... the phalanx soldier cannot operate in either smaller units or singly, whereas the Roman formation is highly flexible. Every Roman soldier ... can adapt himself equally well to any place of time and meet an attack from any quarter ... Accordingly, since the effective use of parts of the Roman army is so much superior, their plans are much more likely to achieve success.

Versus Pyrrhus

See also: Pyrrhus of EpirusThe Greek king Pyrrhus' phalangical system was to prove a tough trial for the Romans. Despite several defeats, the Romans inflicted such losses on the Epirote army that the phrase "Pyrrhic victory" has become a byword for a victory won at a terrible cost. A skilful and experienced commander, Pyrrhus deployed a typically mixed phalanx system, including shock units of war-elephants, and formations of light infantry (peltasts), elite units, and cavalry to support his infantry. Using these he was able to defeat the Romans twice, with a third battle deemed inconclusive or a limited Roman tactical success by many scholars. The battles below (see individual articles for detailed accounts) illustrate the difficulties of fighting against phalanx forces. If well-led and deployed (compare Pyrrhus to the fleeing Perseus at Pydna below), they presented a credible infantry alternative to the heavy legion. The Romans, however, were to learn from their mistakes. In subsequent battles after the Pyrrhic wars, they showed themselves masters of the Hellenic phalanx.

Notable triumphs

Battle of Cynoscephalae

Main article: Battle of CynoscephalaeIn this battle the Macedonian phalanx originally held the high ground but all of its units had not been properly positioned due to earlier skirmishing. Nevertheless, an advance by its left wing drove back the Romans, who counterattacked on the right flank and made some progress against a somewhat disorganized Macedonian left. However, the issue was still in doubt until an unknown tribune (officer) detached twenty maniples from the Roman line and made an encircling attack against the Macedonian rear. This caused the enemy phalanx to collapse, securing a route for the Romans. The more flexible, streamlined organization had exploited the weaknesses of the densely packed phalanx. Such triumphs secured Roman hegemony in Greece and adjoining lands.

Battle of Pydna

Main article: Battle of PydnaAt Pydna the contenders deployed on a relatively flat plain, and the Macedonians had augmented the infantry with a sizeable cavalry contingent. At the hour of decision, the enemy phalanx advanced in formidable array against the Roman line and made some initial progress. However, the ground it had to advance over was rough, and the powerful phalangial formation lost its tight cohesion. The Romans absorbed the initial shock and came on into the fray, where their more spacious formation and continuously applied pressure proved decisive in hand-to-hand combat on the rough ground. Shield and sword at close quarters on such terrain neutralized the sarissa, and supplementary Macedonian weapons (lighter armour and a dagger-like short sword) made an indifferent showing against the skilful and aggressive assault of the heavy Roman infantrymen. The opposition also failed to deploy supporting forces effectively to help the phalanx at its time of dire need. Indeed, the Macedonian commander, Perseus, seeing the situation deteriorating, seems to have fled without even bringing his cavalry into the engagement. The affair was decided in less than two hours, with a comprehensive defeat for the Macedonians.

Other anti-phalanx tactics

Breaking phalanxes illustrates more of the Roman army's flexibility. When the Romans faced phalangite armies, the legions often deployed the velites in front of the enemy with the command to contendite vestra sponte (attack), presumably with their javelins, to cause confusion and panic in the solid blocks of phalanxes. Meanwhile, auxilia archers were deployed on the wings of the legion in front of the cavalry, in order to defend their withdrawal. These archers were ordered to eiaculare flammas, fire incendiary arrows into the enemy. The cohorts then advanced in a wedge formation, supported by the velites and auxiliaries' fire, and charged into the phalanx at a single point, breaking it, then flanking it with the cavalry to seal the victory. See the Battle of Beneventum for evidence of fire-arrows being used.

Versus Hannibal's Carthage

Tactical superiority of Hannibal's forces. While not a classic phalanx force, Hannibal's army was composed of "mixed" contingents and elements common to Hellenic formations, and it is told that towards the end of his life, Hannibal reportedly named Pyrrhus as the commander of the past that he most admired Rome however had blunted Pyrrhus' hosts prior to the rise of Hannibal, and given their advantages in organization, discipline, and resource mobilization, why did they not make a better showing in the field against the Carthaginian, who throughout most of his campaign in Italy suffered from numerical inferiority and lack of support from his homeland?

Hannibal's individual genius, the steadiness of his core troops (forged over several years of fighting together in Spain, and later in Italy) and his cavalry arm seem to be the decisive factors. Time after time Hannibal exploited the tendencies of the Romans, particularly their eagerness to close and achieve a decisive victory. The cold, tired, wet legionaries that slogged out of the Trebia River to form up on the river bank are but one example of how Hannibal forced or manipulated the Romans into fighting on his terms, and on the ground of his own choosing. The later debacles at Lake Trasimene and Cannae, forced the proud Romans to avoid battle, shadowing the Carthaginians from the high ground of the Apennines, unwilling to risk a significant engagement on the plains where the enemy cavalry held sway.

Growing Roman tactical sophistication and ability to adapt overcome earlier disasters. But while the case of Hannibal underscored that the Romans were far from invincible, it also demonstrated their long-term strengths. Rome had a vast manpower surplus far outnumbering Hannibal that gave them more options and flexibility. They isolated and eventually bottled up the Carthaginians and hastened their withdrawal from Italy with the constant manoeuvre. More importantly, they used their manpower resources to launch an offensive into Spain and Africa. They were willing to absorb the humiliation in Italy and remain on the strategic defensive, but with typical relentless persistence they struck elsewhere, to finally crush their foes.

They also learned from those enemies. The operations of Scipio were an improvement on some of those who had previously faced Hannibal, showing a higher level of advance thinking, preparation and organization. (Compare with Sempronius at the Battle of the Trebia River for example). Scipio's contribution was in part to implement more flexible manoeuvre of tactical units, instead of the straight-ahead, three-line grind favoured by some contemporaries. He also made better use of cavalry, traditionally an arm in which the Romans were lacking. His operations also included pincer movements, a consolidated battle line, and "reverse Cannae" formations and cavalry movements. His victories in Spain and the African campaign demonstrated a new sophistication in Roman warfare and reaffirmed the Roman capacity to adapt, persist and overcome. See detailed battles:

Roman infantry versus Gallic and the Germanic tribes

Barbarian armies

Views of the Gallic enemies of Rome have varied widely. Some older histories consider them to be backward savages, ruthlessly destroying the civilization and "grandeur that was Rome". Some modernist views see them in a proto-nationalist light, ancient freedom fighters resisting the iron boot of empire. Often their bravery is celebrated as worthy adversaries of Rome. See the Dying Gaul for an example. The Gallic opposition was also composed of a large number of different peoples and tribes, geographically ranging from the mountains of Switzerland to the lowlands of France and thus are not easy to categorize. The term Gaul has also been used interchangeably to describe Celtic peoples farther afield in Britain adding even more to the diversity of peoples lumped together under this name. From a military standpoint, however, they seem to have shared certain general characteristics: tribal polities with a relatively small and lesser elaborated state structure, light weaponry, fairly unsophisticated tactics and organization, a high degree of mobility, and inability to sustain combat power in their field forces over a lengthy period. Roman sources reflect on the prejudices of their times, but nevertheless testify to the Gauls' fierceness and bravery.

- Their chief weapons were long, two-edged swords of soft iron. For defence, they carried small wicker shields. Their armies were undisciplined mobs, greedy for plunder ... Brave to the point of recklessness, they were formidable warriors, and the ferocity of their first assault inspired terror even in the ranks of veteran armies.

Early Gallic victories

Though popular accounts celebrate the legions and an assortment of charismatic commanders quickly vanquishing massive hosts of "wild barbarians", Rome suffered a number of early defeats against such tribal armies. As early as the Republican period (circa 390–387 BC), they had sacked Rome under Brennus, and had won several other victories such as the Battle of Noreia and the Battle of Arausio. The foremost Gallic triumph in this early period was "The Day of Allia" (July 18) when Roman troops were routed and driven into the Allia River. Henceforth, July 18 was considered an unlucky date on the Roman calendar.

Some writers suggest that as a result of such debacles, the expanding Roman power began to adjust to this vigorous, fast-moving new enemy. The Romans began to phase out the monolithic phalanx they formerly fought in and adopted the more flexible manipular formation. The circular hoplite shield was also enlarged and eventually replaced with the rectangular scutum for better protection. The heavy phalanx spear was replaced by the pila, suitable for throwing. Only the veterans of the triarii retained the long spear – vestige of the former phalanx. Such early reforms also aided the Romans in their conquest of the rest of Italy over such foes as the Samnites, Latins, and Greeks. As time went on Roman arms saw increasing triumph over the Gauls, particularly in the campaigns of Caesar. In the early imperial period, however, Germanic warbands inflicted one of Rome's greatest military defeats (the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest), which saw the destruction of three imperial legions and was to place a limit on Roman expansion in the West. And it was these Germanic tribes in part (most having some familiarity with Rome and its culture, and becoming more Romanized themselves) that were to eventually bring about the Roman military's final demise in the West. Ironically, in the final days, the bulk of the fighting was between forces composed mostly of barbarians on either side.

Tactical performance versus Gallic and Germanic opponents

Gallic and Germanic strengths

Whatever their particular culture, the Gallic and Germanic tribes generally proved themselves to be tough opponents, racking up several victories over their enemies. Some historians show that they sometimes used massed fighting in tightly packed phalanx-type formations with overlapping shields, and employed shield coverage during sieges. In open battle, they sometimes used a triangular "wedge" style formation in attack. Their greatest hope of success lay in four factors: (a) numerical superiority, (b) surprising the Romans (via an ambush for example), (c) advancing quickly to the fight, or (d) engaging the Romans over heavily covered or difficult terrain where units of the fighting horde could shelter within striking distance until the hour of decision, or if possible, withdraw and regroup between successive charges.

Most significant Gallic and Germanic victories show two or more of these characteristics. The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest contains all four: numerical superiority, surprise, quick charges to close rapidly, and favorable terrain and environmental conditions (thick forest and pounding rainstorms) that hindered Roman movement and gave the warriors enough cover to conceal their movements and mount successive attacks against the Roman line. Another factor in the Romans' defeat was a treacherous defection by Arminius and his contingent.

Gallic and Germanic weaknesses

Weaknesses in organization and equipment. Against the fighting men from the legion however, the Gauls, Iberians and Germanic forces faced a daunting task. The barbarians' rudimentary organization and tactics fared poorly against the well-oiled machinery that was the Roman legion. The fierceness of the Gallic and Germanic charges is often commented upon by some writers, and in certain circumstances, they could overwhelm Roman lines. Nevertheless, the in-depth Roman formation allowed adjustments to be made, and the continual application of forwarding pressure made long-term combat a hazardous proposition for the Gauls.

Flank attacks were always possible, but the legion was flexible enough to pivot to meet this, either through sub-unit manoeuvre or through the deployment of lines farther back. The cavalry screen on the flanks also added another layer of security, as did nightly regrouping in fortified camps. The Gauls and Germans also fought with little or no armour and with weaker shields, putting them at a disadvantage against the legion. Other items of Roman equipment from studded sandals, to body armour, to metal helmets added to Roman advantages. Generally speaking, the Gauls and Germans needed to get into good initial position against the Romans and to overwhelm them in the early phases of the battle. An extended set-piece slogging match between the lightly armed tribesmen and the well-organized heavy legionaries usually spelt doom for the tribal fighters. Caesar's slaughter of the Helvetii near the Saône River is just one example of tribal disadvantage against the well-organized Romans, as is the victory of Germanicus at the Weser River and Agricola against the Celtic tribesmen of Caledonia (Scotland) circa 84 AD.

Weaknesses in logistics. Roman logistics also provided a trump card against Germanic foes as it had against so many previous foes. Tacitus in his Annals reports that the Roman commander Germanicus recognized that continued operations in Gaul would require long trains of men and material to come overland, where they would be subject to attack as they traversed the forests and swamps. He, therefore, opened sea and river routes, moving large quantities of supplies and reinforcements relatively close to the zone of battle, bypassing the dangerous land routes. In addition, the Roman fortified camps provided secure staging areas for offensive, defensive and logistical operations, once their troops were deployed. Assault roads and causeways were constructed on the marshy ground to facilitate manoeuvre, sometimes under direct Gallic attack. These Roman techniques repeatedly defeated their Germanic adversaries. While Germanic leaders and fighters influenced by Roman methods sometimes adapted them, most tribes did not have the strong organization of the Romans. As German scholar Hans Delbruck notes in his "History of the Art of War":

- ... The superiority of the Roman art of warfare was based on the army organization ... a system that permitted very large masses of men to be concentrated at a given point, to move in an orderly fashion, to be fed, to be kept together. The Gauls could do none of these things.

Gallic and Germanic chariots

The Gauls also demonstrated a high level of tactical prowess in some areas. Gallic chariot warfare, for example, showed a high degree of integration and coordination with infantry, and Gallic horse and chariot assaults sometimes threatened Roman forces in the field with annihilation. At the Battle of Sentinum for example, c. 295 BC, the Roman and Campanian cavalry encountered Gallic war-chariots and were routed in confusion – driven back from the Roman infantry by the unexpected appearance of the fast-moving Gallic assault. The discipline of the Roman infantry restored the line, however, and a counter-attack eventually defeated the Gallic forces and their allies.

The accounts of Polybius leading up to the Battle of Telamon (c. 225 BC) mention chariot warfare, but it was ultimately unsuccessful. The Gauls met comprehensive defeat by the Roman legions under Papus and Regulus. Chariot forces also attacked the legions as they were disembarking from ships during Caesar's invasion of Britain, but the Roman commander drove off the fast-moving assailants using covering fire (slings, arrows and engines of war) from his ships and reinforcing his shore party of infantry to charge and drive off the attack. In the open field against Caesar, the Gallic/Celtics apparently deployed chariots with a driver and an infantry fighter armed with javelins. During the clash, the chariots would drop off their warriors to attack the enemy and retire a short distance away, massed in reserve. From this position, they could retrieve the assault troops if the engagement was going badly, or apparently, pick them up and deploy elsewhere. Caesar's troops were discomfited by one such attack, and he met it by withdrawing into his fortified redoubt. A later Gallic attack against the Roman camp was routed.

Superb as the Gallic fighters were, chariots were already declining as an effective weapon of war in the ancient world with the rise of mounted cavalry. At the Battle of Mons Graupius in Caledonia (circa 84 AD), Celtic chariots made an appearance. However, they were no longer used in an offensive role but primarily for the pre-battle show – riding back and forth and hurling insults. The main encounter was decided by infantry and mounted cavalry.

Superior tactical organization: victory of Caesar at the Sambre River

Superior Gallic mobility and numbers often troubled Roman arms, whether deployed in decades-long mobile or guerrilla warfare or in decisive field engagement. The near-defeat of Caesar in his Gallic campaign confirms this latter pattern but also shows the strengths of Roman tactical organization and discipline. At the Battle of the Sabis river, contingents of the Nervii, Atrebates, Veromandui and Aduatuci tribes massed secretly in the surrounding forests as the main Roman force was busy making camp on the opposite side of the river. Some distance away behind them slogged two slow-moving legions with the baggage train. Engaged in foraging and camp construction the Roman forces were somewhat scattered. As camp building commenced, the barbarian forces launched a ferocious attack, streaming across the shallow water and quickly assaulting the distracted Romans. This incident is discussed in Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico.

So far the situation looked promising for the warrior host. The four conditions above were in their favour: (a) numerical superiority, (b) the element of surprise, (c) a quick advance/assault, and (d) favourable terrain that masked their movements until the last minute. Early progress was spectacular as the initial Roman dispositions were driven back. A rout looked possible. Caesar himself rallied sections of his endangered army, impressing resolve upon the troops. With their customary discipline and cohesion, the Romans then began to drive back the barbarian assault. A charge by the Nervi tribe through a gap between the legions, however, almost turned the tide again, as the onrushing warriors seized the Roman camp and tried to outflank the other army units engaged with the rest of the tribal host. The initial phase of the clash had passed and a slogging match ensued. The arrival of the two rear legions that had been guarding the baggage reinforced the Roman lines. Led by the 10th Legion, a counter-attack was mounted with these reinforcements that broke the back of the barbarian effort and sent the tribesmen reeling in retreat. It was a close-run thing, illustrating both the fighting prowess of the tribal forces and the steady, disciplined cohesion of the Romans. Ultimately, the latter was to prove decisive in Rome's long fought conquest of Gaul.

Persisting logistics strategy: Gallic victory at Gergovia

As noted above, the fierce charge of the Gauls and their individual prowess is frequently acknowledged by several ancient Roman writers. The Battle of Gergovia demonstrates that the Gallic were capable of a level of strategic insight and operation beyond merely mustering warriors for an open field clash. Under their war leader Vercingetorix, the Gauls pursued what some modern historians have termed a "persisting" or "logistics strategy" – a mobile approach relying not on direct open field clashes, but avoidance of major battle, "scorched earth" denial of resources, and the isolation and piecemeal destruction of Roman detachments and smaller unit groupings. When implemented consistently, this strategy saw some success against Roman operations. According to Caesar himself, during the siege of the town of Bourges, the lurking warbands of Gauls were:

- ... on the watch for our foraging and grain-gatherer parties, when necessarily scattered far afield he attacked them and inflicted serious losses ... This imposed such scarcity upon the army that for several days they were without grain and staved off starvation only by driving cattle from remote villages.

Caesar countered with a strategy of enticing the Gallic forces out into open battle, or of blockading them into submission.

At the town of Gergovia, resource denial was combined with a concentration of superior force and multiple threats from more than one direction. This caused the opposing Roman forces to divide and ultimately fail. Gergovia was situated on the high ground of a tall hill and Vercingetorix carefully drew up the bulk of his force on the slope, positioning allied tribes in designated places. He drilled his men and skirmished daily with the Romans, who had overrun a hilltop position and had created a small camp some distance from Caesar's larger main camp. A rallying of about 10,000 disenchanted Aeudan tribesmen (engineered by Vercingetorix's agents) created a threat in Caesar's rear, including a threat to a supply convoy promised by the allied Aeudans, and he diverted four legions to meet this danger. This, however, gave Vercingetorix's forces the chance to concentrate in superior strength against the smaller two-legion force left behind at Gergovia, and desperate fighting ensued. Caesar dealt with the real threat, turned around and by ruthlessly forced marching once again consolidated his forces at the town. A feint using bogus cavalry by the Romans drew off part of the Gallic assault, and the Romans advanced to capture three more enemy outposts on the slope, and proceeded towards the walls of the stronghold. The diverted Gallic forces returned however and in frantic fighting outside the town walls, the Romans lost 700 men, including 46 centurions.

Caesar commenced a retreat from the town with the victorious Gallic warriors in pursuit. The Roman commander, however, mobilized his 10th Legion as a blocking force to cover his withdrawal and after some fighting, the tribesmen themselves withdrew back to Gergovia, taking several captured legion standards. The vicious fighting around Gergovia was the first time Caesar had suffered a military reverse, demonstrating the Gallic martial valor noted by the ancient chroniclers. The hard battle is referenced by the Roman historian Plutarch, who writes of the Averni people showing visitors a sword in one of their temples, a weapon that reputedly belonged to Caesar himself. According to Plutarch, the Roman general was shown the sword in the temple at Gergovia some years after the battle, but he refused to reclaim it, saying that it was consecrated, and to leave it where it was.