| Revision as of 02:39, 29 March 2021 editErminwin (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,523 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:38, 11 April 2021 edit undoOsamaorf (talk | contribs)10 edits Corrected the phrasing of Kashgari and what he meant. In his book languages of Turkic people, the word language meant dialect. As he refers to Uyghur Turkic as "Uyghur language". And removed a resource based on hunches not evidence and does not fit in the context of the evidence being discussed as it has not credible value whatsoever.Tags: Reverted references removed Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

| Persian historian ] listed Tatars as one of seven founding tribes of the Turkic ].<ref>Martinez A.P. 1982 "Gardīzī’s two chapters on the Turks". ''Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi'', vol. II: 120-121 cited in Tishin V.V. (2018). p. 107-108</ref> The Shine Usu inscription mentioned that the Toquz Tatars, in alliance with the Sekiz-Oghuz,{{efn|"Eight Oghuzes", an ethnonym which denotes the eight tribes who'd revolted against the leading Uyghur tribe, according to Czeglédy<ref>Czeglédy, Karoly (1972) "On the Numerical Composition of the Ancient Turkish Trial Confederations" in ''Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae'' Akadémiai Kiadó</ref>}} unsuccessfully revolted against Uyghur Khagan ], who was consolidating power between 744-750 CE.<ref>"Moghon Shine Usu Inscription" at ''Türik Bitig''</ref><ref>Kamalov, A. (2003) "The Moghon Shine Usu Insription as the Earliest Uighur Historical Annals", ''Central Asiatic Journal''. '''47''' (1). p. 77-90</ref> After being defeated three times, half of the Oghuz-Tatar rebels rejoined the Uyghurs, while the other half fled to an unknown people, who were identified as ]<ref>Ramstedt, G.I. (1913) "Zwei Uighurischen Runeinschriften", p. 52. cited in Kamalov (2003), p. 86</ref> or ].<ref>Czegledy, K. (1973) "Gardizi on the History of Central Asia", p. 265. cited in Kamalov (2003), p. 86</ref> According to Senga and Klyashtorny, part of the Toquz-Tatar rebels fled westwards from the Uyghurs to the ] river basin, where they later organized the ] and other tribal groupings (either already there or also newly arrived) into the Kimek tribal union.<ref>Senga cited in Golden (2002) “Notes on the Qïpchaq Tribes: Kimeks and Yemeks”, in ''The Turks'', '''I''', p. 662</ref><ref>Klyashtorny, S.G. (1997) in ''International Journal of Eurasian Studies'' '''2'''</ref> | Persian historian ] listed Tatars as one of seven founding tribes of the Turkic ].<ref>Martinez A.P. 1982 "Gardīzī’s two chapters on the Turks". ''Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi'', vol. II: 120-121 cited in Tishin V.V. (2018). p. 107-108</ref> The Shine Usu inscription mentioned that the Toquz Tatars, in alliance with the Sekiz-Oghuz,{{efn|"Eight Oghuzes", an ethnonym which denotes the eight tribes who'd revolted against the leading Uyghur tribe, according to Czeglédy<ref>Czeglédy, Karoly (1972) "On the Numerical Composition of the Ancient Turkish Trial Confederations" in ''Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae'' Akadémiai Kiadó</ref>}} unsuccessfully revolted against Uyghur Khagan ], who was consolidating power between 744-750 CE.<ref>"Moghon Shine Usu Inscription" at ''Türik Bitig''</ref><ref>Kamalov, A. (2003) "The Moghon Shine Usu Insription as the Earliest Uighur Historical Annals", ''Central Asiatic Journal''. '''47''' (1). p. 77-90</ref> After being defeated three times, half of the Oghuz-Tatar rebels rejoined the Uyghurs, while the other half fled to an unknown people, who were identified as ]<ref>Ramstedt, G.I. (1913) "Zwei Uighurischen Runeinschriften", p. 52. cited in Kamalov (2003), p. 86</ref> or ].<ref>Czegledy, K. (1973) "Gardizi on the History of Central Asia", p. 265. cited in Kamalov (2003), p. 86</ref> According to Senga and Klyashtorny, part of the Toquz-Tatar rebels fled westwards from the Uyghurs to the ] river basin, where they later organized the ] and other tribal groupings (either already there or also newly arrived) into the Kimek tribal union.<ref>Senga cited in Golden (2002) “Notes on the Qïpchaq Tribes: Kimeks and Yemeks”, in ''The Turks'', '''I''', p. 662</ref><ref>Klyashtorny, S.G. (1997) in ''International Journal of Eurasian Studies'' '''2'''</ref> | ||

| Writing in the 11th century, ] scholar ] included contemporary Tatars among the Turkic peoples,{{efn|When listing the 20 Turkic tribes, Kashgari also included non-Turks such as ], ], and ] (the last one rendered as {{lang-ar|Tawġāj}} < ] *'']'')<ref>Golden (1992) p. 229</ref><ref>Biran, Michal (2005), ''The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World'', Cambridge University Press. p. 98</ref> }} located the Tatars west of the |

Writing in the 11th century, ] scholar ] included contemporary Tatars among the Turkic peoples,{{efn|When listing the 20 Turkic tribes, Kashgari also included non-Turks such as ], ], and ] (the last one rendered as {{lang-ar|Tawġāj}} < ] *'']'')<ref>Golden (1992) p. 229</ref><ref>Biran, Michal (2005), ''The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World'', Cambridge University Press. p. 98</ref> }} located the Tatars west of the Ili river.<ref>Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In ''Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature''. Part I. (1982). p. 82-83</ref> Kashgari addionally noted that Tatars were speaking ] alongside their own language (and here he most likely meant dialect, as he refers to some Uyghur words later in the book as the Uyghur language). the same for the Qay, and Yabaqus.<ref>al-Kašğari. p. 82-83</ref> | ||

| As for the division of Tatars who remained east, by the 10th century, they became subjects of the ]-led ]. After the fall of the Liao, the Tatars experienced pressure from the ]-led ] and were urged to fight against the other Mongol tribes. The Tatars lived on the fertile pastures around ] and ] and occupied a trade route to ] in the 12th century. ] ambassador Zhao Hong wrote in 1221 that in ]'s ], there were three divisions based on their distance from the ]-ruled China: the White Tatars (白韃靼 ''Bai Dada''), the Black Tatars (黑韃靼 ''Hei Dada''), and the Wild Tatars (生韃靼 ''Sheng Dada''),<ref>Theobald, Ulrich (2012) in ''ChinaKnowledge.de''</ref> who were identified, by Kyzlasov, with the Turkic-speakers - including the ]s (of Turkic ] origin),<ref>]'', "阿剌兀思剔吉忽里,汪古部人,係出沙陀雁門之後。" Ala Qus Tigin-qori, a man of the Ongud tribe, descending from the ]'s Shatuo</ref><ref>Paulillo, Maurizio. "White Tatars: The Problem of the Öngũt conversion to Jingjiao and the Uighur Connection" in ''From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia'' (orientalia - patristica - oecumenica) Ed. Tang, Winkler. (2013) pp. 237-252</ref> Mongolic speakers -to whom belonged Genghis Khan and his companions-, and the ] speakers,{{efn|Xin Wudaishi also mentioned the Tungusic background of some Tatars<ref>], txt: "達靼,靺鞨之遺種,本在奚、契丹之東北,後為契丹所攻,而部族分散,或屬契丹,或屬渤海,別部散居陰山者,自號達靼。" tr: "Tatars, remnant stock of ]. Originally they dwelt the ], northeast of the Khitans. Later they were attacked by Khitans, and the tribe was scattered. either submitted to Khitans, or submitted to ]. As for tribes separated and living scattered at ], called themselves Tatars"</ref>}} respectively.<ref name="sadur" /> | As for the division of Tatars who remained east, by the 10th century, they became subjects of the ]-led ]. After the fall of the Liao, the Tatars experienced pressure from the ]-led ] and were urged to fight against the other Mongol tribes. The Tatars lived on the fertile pastures around ] and ] and occupied a trade route to ] in the 12th century. ] ambassador Zhao Hong wrote in 1221 that in ]'s ], there were three divisions based on their distance from the ]-ruled China: the White Tatars (白韃靼 ''Bai Dada''), the Black Tatars (黑韃靼 ''Hei Dada''), and the Wild Tatars (生韃靼 ''Sheng Dada''),<ref>Theobald, Ulrich (2012) in ''ChinaKnowledge.de''</ref> who were identified, by Kyzlasov, with the Turkic-speakers - including the ]s (of Turkic ] origin),<ref>]'', "阿剌兀思剔吉忽里,汪古部人,係出沙陀雁門之後。" Ala Qus Tigin-qori, a man of the Ongud tribe, descending from the ]'s Shatuo</ref><ref>Paulillo, Maurizio. "White Tatars: The Problem of the Öngũt conversion to Jingjiao and the Uighur Connection" in ''From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia'' (orientalia - patristica - oecumenica) Ed. Tang, Winkler. (2013) pp. 237-252</ref> Mongolic speakers -to whom belonged Genghis Khan and his companions-, and the ] speakers,{{efn|Xin Wudaishi also mentioned the Tungusic background of some Tatars<ref>], txt: "達靼,靺鞨之遺種,本在奚、契丹之東北,後為契丹所攻,而部族分散,或屬契丹,或屬渤海,別部散居陰山者,自號達靼。" tr: "Tatars, remnant stock of ]. Originally they dwelt the ], northeast of the Khitans. Later they were attacked by Khitans, and the tribe was scattered. either submitted to Khitans, or submitted to ]. As for tribes separated and living scattered at ], called themselves Tatars"</ref>}} respectively.<ref name="sadur" /> | ||

Revision as of 20:38, 11 April 2021

Further information: Tatars and Tartary| Tatar Nine Tatars | |

|---|---|

| 8th century–1202 | |

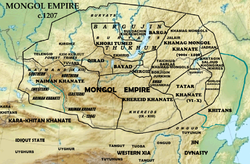

Tatar and their neighbours in the 13th century. Tatar and their neighbours in the 13th century. | |

| Status | nomadic confederation |

| Common languages | Common Mongolic, Turkic |

| Religion | Tengrism |

| Government | Elective monarchy |

| chief | |

| Legislature | Kurultai |

| Historical era | High Middle Ages |

| • Established | 8th century |

| • Disestablished | 1202 |

| Today part of | Mongolia China |

Tatar (Template:Lang-otk; Chinese: 塔塔兒) was one of the five major tribal confederations (khanlig) in the Mongolian Plateau in the 12th century.

The name "Tatar" was first transliterated in Book of Song as 大檀 Dàtán (MC: *da-dan) and 檀檀 Tántán (MC: *dan-dan) as other names of the Rourans, who were of Proto-Mongolic Donghu ancestry. The Book of Song and Book of Liang connected Rourans to the earlier Xiongnu while the Book of Wei traced the Rouran's origins back to the Donghu. Xu proposed that "the main body of the Rouran were of Xiongnu origin" and Rourans' descendants, namely Da Shiwei (aka Tatars), contained Turkic elements to a great extent. Even so, the Xiongnu's language is still unknown, and Chinese historians routinely ascribed Xiongnu origins to various nomadic groups, yet such ascriptions do not necessarily indicate the subjects' exact origins: for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele as well as Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitans.

The Tatars' Rouran ancestors roamed modern-day Mongolia in summer and crossed the Gobi desert southwards in winter in search of pastures. Rourans founded their Khaganate in the 5th century, around 402 CE. Among the Rourans' subjects were the Ashina tribe, who overthrew their Rouran overlords in 552 and annihilated the Rourans in 555. One branch of the dispersed Rourans migrated to Greater Khingan mountain range where they renamed themselves after Tantan, a historical Khagan, and gradually incorporated themselves into the Shiwei tribal complex and emerged as 大室韋 Da (Great) Shiwei.

The first precise transcription of the Tatar ethnonym was written in Turkic on the Orkhon inscriptions, specifically, the Kul Tigin (CE 732) and Bilge Khagan (CE 735) monuments as Template:Lang-otk and Template:Lang-otk referring to the Tatar confederation.

The Toquz-Tatars and Otuz-Tatars were often proposed to be Mongolic speakers. In contrast, Soviet and Russian orientalist Leonid Kyzlasov, the Toquz Tatars and Otuz Tatars were instead Turkic-speaking, as the Persian-authored 10th century geographical treatise Hudud al-Alam stated that Tatars were part of the Toghuzghuz, whom Minorsky identified with the Qocho kingdom in eastern Tianshan, founded by Uyghur refugees following the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate, whose founders belonged to the Toquz Oghuz confederation.

Persian historian Gardizi listed Tatars as one of seven founding tribes of the Turkic Kimek confederation. The Shine Usu inscription mentioned that the Toquz Tatars, in alliance with the Sekiz-Oghuz, unsuccessfully revolted against Uyghur Khagan Bayanchur, who was consolidating power between 744-750 CE. After being defeated three times, half of the Oghuz-Tatar rebels rejoined the Uyghurs, while the other half fled to an unknown people, who were identified as Khitans or Karluks. According to Senga and Klyashtorny, part of the Toquz-Tatar rebels fled westwards from the Uyghurs to the Irtysh river basin, where they later organized the Kipchaks and other tribal groupings (either already there or also newly arrived) into the Kimek tribal union.

Writing in the 11th century, Kara-khanid scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari included contemporary Tatars among the Turkic peoples, located the Tatars west of the Ili river. Kashgari addionally noted that Tatars were speaking Turkic alongside their own language (and here he most likely meant dialect, as he refers to some Uyghur words later in the book as the Uyghur language). the same for the Qay, and Yabaqus.

As for the division of Tatars who remained east, by the 10th century, they became subjects of the Khitan-led Liao dynasty. After the fall of the Liao, the Tatars experienced pressure from the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty and were urged to fight against the other Mongol tribes. The Tatars lived on the fertile pastures around Hulun Nuur and Buir Nuur and occupied a trade route to China proper in the 12th century. Southern Song ambassador Zhao Hong wrote in 1221 that in Genghis Khan's Mongol empire, there were three divisions based on their distance from the Jurchen Jin-ruled China: the White Tatars (白韃靼 Bai Dada), the Black Tatars (黑韃靼 Hei Dada), and the Wild Tatars (生韃靼 Sheng Dada), who were identified, by Kyzlasov, with the Turkic-speakers - including the Öngüds (of Turkic Shatuo origin), Mongolic speakers -to whom belonged Genghis Khan and his companions-, and the Tungusic speakers, respectively.

Notes

- in Sadur (2012:250), the Toquz Oghuz/Qocho Uyghurs were misidentified with the Oghuz Turks who founded, in the late 8th cenrtury, a nomadic state spanning from the Syr Darya's lower reaches to the Caspian Sea; even though the Toghuzghuz country's locations, given by the Hudud, are identifiable with Qocho kingdom's locations: e.g. Chīnānjikath with Gaochang, Ṭafqān with Eastern Tianshan, Panjīkath with Besh Balïq, etc.

- "Eight Oghuzes", an ethnonym which denotes the eight tribes who'd revolted against the leading Uyghur tribe, according to Czeglédy

- When listing the 20 Turkic tribes, Kashgari also included non-Turks such as Khitans, Tanguts, and Chinese (the last one rendered as Template:Lang-ar < Karakhanid *Tawğač)

- Xin Wudaishi also mentioned the Tungusic background of some Tatars

References

- ^ Rybatzki, Volker (2011). "Classification of Old Turkic loanwords in Mongolic". In Ölmez, Mehmet; Aydın, Erhan; Zieme, Peter; Kaçalin, Mustafa (eds.). From Ötüken to Istanbul: 1290 Years of Turkish (720 - 2010). p. 186.

The Common Mongolic of this time might be connected with two ethnic groups called Otuz Tatar or Toquz Tatar in the Old Turkic inscriptions

- ^ Sadur Valiahmet: Тюрки, татары, мусульмане, 2012, page 250

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54-56.

- Songshu vol. 95. "芮芮一號大檀,又號檀檀" tr. "Ruìruì, one appellation is Dàtán, also called Tántán"

- Weishu vol. 103 "蠕蠕,東胡之苗裔也,姓郁久閭氏。" tr. "Rúrú, offsprings of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ""

- *Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity", Early China. p. 20

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 54-55.

- ^ Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 179-180

- Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. 59 (1–2): 116.

It is not known which language the Xiongnu spoke.

- Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal. 59 (1–2): 105.

- Weishu, vol. 103 "冬則徙度漠南,夏則還居漠北。"In winter moved southwards across the desert; in summer returned northwards to dwell in the desert."

- Kradin, N.N. "From Tribal Confederation to Enpire: The Evolution of Rouran Society" in Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 58 (2), (2005). p. 149-151, 158, 160 of 149–169

- "Kül Tiğin (Gültekin) Yazıtı Tam Metni (Full text of Kul Tigin monument with Turkish transcription)". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "Bilge Kağan Yazıtı Tam Metni (Full text of Bilge Khagan monument with Turkish transcription)". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "The Kultegin's Memorial Complex". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Ross, E. Denison; Vilhelm Thomsen (1930). "The Orkhon Inscriptions: Being a Translation of Professor Vilhelm Thomsen's Final Danish Rendering". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 5 (4, 1930): 861–876. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00090558. JSTOR 607024.

- Thomsen, Vilhelm Ludvig Peter (1896). Inscriptions de l'Orkhon déchiffrées. Helsingfors, Impr. de la Société de littérature finnoise. p. 140.

- Köprülü, Mehmet Fuad (2006) Early Mystic in Turkish literature translated by Leiser and Dankoff. p. 146-148

- Golden P.B. (1992) An Introduction to the History of the Turkic peoples. Series: Turcologica, IX. Wiesbaden: Otto-Harrassowitz. p. 145

- Theoblad, U. (2012) "Dada 韃靼, Tatars" for ChinaKnowledge.de

- Ḥudūd al'Ālam "Section 12" Translated and Explained by V. F. Minorsky (1937) p. 94. quote: "The Tātār too are a race (jinsī) of the Toghuzghuz"

- Minorsky, V.F. (1937) "Commentary" on Ḥudūd al'Ālam, "Section 18". p. 263-265

- Golden P.B. (1992) p. 155-157

- Minorsky (1937). p. 271-272

- Martinez A.P. 1982 "Gardīzī’s two chapters on the Turks". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi, vol. II: 120-121 cited in Tishin V.V. (2018). "Kimäk and Chù-mù-kūn (处木昆): Notes on an Identification" p. 107-108

- Czeglédy, Karoly (1972) "On the Numerical Composition of the Ancient Turkish Trial Confederations" in Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Akadémiai Kiadó

- "Moghon Shine Usu Inscription" text at Türik Bitig

- Kamalov, A. (2003) "The Moghon Shine Usu Insription as the Earliest Uighur Historical Annals", Central Asiatic Journal. 47 (1). p. 77-90

- Ramstedt, G.I. (1913) "Zwei Uighurischen Runeinschriften", p. 52. cited in Kamalov (2003), p. 86

- Czegledy, K. (1973) "Gardizi on the History of Central Asia", p. 265. cited in Kamalov (2003), p. 86

- Senga cited in Golden (2002) “Notes on the Qïpchaq Tribes: Kimeks and Yemeks”, in The Turks, I, p. 662

- Klyashtorny, S.G. (1997) "The Oguzs of the Central Asia and The Guzs of the Aral Region" in International Journal of Eurasian Studies 2

- Golden (1992) p. 229

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press. p. 98

- Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. Part I. (1982). p. 82-83

- al-Kašğari. p. 82-83

- Theobald, Ulrich (2012) "Dada 韃靼, Tatars" in ChinaKnowledge.de

- History of Yuan, "Vol. 118" "阿剌兀思剔吉忽里,汪古部人,係出沙陀雁門之後。" Ala Qus Tigin-qori, a man of the Ongud tribe, descending from the Wild Goose Pass's Shatuo

- Paulillo, Maurizio. "White Tatars: The Problem of the Öngũt conversion to Jingjiao and the Uighur Connection" in From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia (orientalia - patristica - oecumenica) Ed. Tang, Winkler. (2013) pp. 237-252

- Xin Wudaishi, vol. 74 txt: "達靼,靺鞨之遺種,本在奚、契丹之東北,後為契丹所攻,而部族分散,或屬契丹,或屬渤海,別部散居陰山者,自號達靼。" tr: "Tatars, remnant stock of Mohe. Originally they dwelt the Xi, northeast of the Khitans. Later they were attacked by Khitans, and the tribe was scattered. either submitted to Khitans, or submitted to Balhae. As for tribes separated and living scattered at Yin Mountains, called themselves Tatars"

| Mongolic peoples | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||||||

| Proto-Mongols | |||||||||||

| Medieval tribes | |||||||||||

| Ethnic groups |

| ||||||||||

| See also: Donghu and Xianbei · Turco-Mongol · Modern ethnic groups Mongolized ethnic groups.Ethnic groups of Mongolian origin or with a large Mongolian ethnic component. | |||||||||||

| Turco-Mongol | |

|---|---|

| States | |

| Related ethnic groups and clans | |

| Culture | |

| Origin is controversial. | |