| Revision as of 02:47, 9 October 2022 editRenamed user 0e40c0e52322c484364940c7954c93d8 (talk | contribs)6,278 edits →Reactions in the US: Adding Lindsey Graham and Joe Manchin support, Frida Ghitis warningTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:02, 9 October 2022 edit undoRenamed user 0e40c0e52322c484364940c7954c93d8 (talk | contribs)6,278 edits Correct and update lead, fix problem from Talk:Indictment_and_arrest_of_Julian_Assange#Neutrality_disputeTag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In 2012, while fighting extradition to Sweden for questioning over sex assault claims,<ref name=":6" /> ] applied for and was granted ] by Ecuador<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":6" /> and he remained in the ] in London from 2012 until 2019. On 11 April 2019, his asylum was revoked and he was carried out of the Embassy and arrested by the ] for failing to appear in court.<ref name=":0" /> Following his arrest, a US indictment from 2018 was made public accusing Assange of ] to commit computer intrusion.<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Megerian |first1=Chris |last2=Boyle |first2=Christina |last3=Wilber |first3=Del Quentin |date=11 April 2019 |title=WikiLeaks' Julian Assange faces U.S. hacking charge after dramatic arrest in London |language=en-US |newspaper=] |url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/la-fg-britain-julian-assange-arrested-20190411-story.html |access-date=11 April 2019}}</ref> The charge carries a maximum sentence of five years with a possibility of parole.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/11/world/europe/julian-assange-wikileaks-ecuador-embassy.html |title=Julian Assange Charged by U.S. With Conspiracy to Hack a Government Computer |last1=Sullivan |first1=Eileen |date=11 April 2019 |newspaper=] |access-date=11 April 2019 |last2=Pérez-Peña |first2=Richard |language=en-US |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> | |||

| On 23 May 2019, a US grand jury added 17 ] charges related to his involvement with Chelsea Manning, making a total of 18 federal charges against Assange in the US. The 18 charges could result in a sentence of up to 175 years in prison.<ref name="cbsindicts" /><ref name="aussieassange" /> On 25 June 2020 a new indictment was filed, alleging that Assange attempted to recruit hackers and system administrators at conferences around the world as far back as 2009, and conspired with hackers including members of LulzSec and Anonymous. The indictment also described Assange's alleged efforts to recruit system administrators, Assange and WikiLeaks' role in helping Snowden flee the US, and their use of Snowden as a recruitment tool.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":12" /> | |||

| Assange was arrested on 11 April 2019 by the ] for failing to appear in court, and faces possible extradition to the US.<ref name=":0" /> His arrest caught media attention, and news of it went viral on social media, especially on Twitter and Facebook. Assange himself did not consent to extradition to the US.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-48134901|title=Assange 'doesn't consent' to US extradition|work=BBC|date=2 May 2019|access-date=6 May 2019|language=en-GB}}</ref> | |||

| In response to the indictment, the ]' Editorial Board warned that "The administration has begun well by charging Mr. Assange with an indisputable crime. But there is always a risk with this administration — one that labels the free press as “the enemy of the people” — that the prosecution of Mr. Assange could become an assault on the First Amendment and whistle-blowers."<ref name=":1" /> |

In response to the indictment, the ]' Editorial Board warned that "The administration has begun well by charging Mr. Assange with an indisputable crime. But there is always a risk with this administration — one that labels the free press as “the enemy of the people” — that the prosecution of Mr. Assange could become an assault on the First Amendment and whistle-blowers."<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| On 23 May 2019, a US grand jury added 17 ] charges related to his involvement with Chelsea Manning, making a total of 18 federal charges against Assange in the US. The 18 charges could result in a sentence of up to 175 years in prison.<ref name="cbsindicts" /><ref name="aussieassange" /> | |||

| In December 2021, the ] ruled that Assange may be extradited to the US.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/dec/10/julian-assange-can-be-extradited-to-us-to-face-espionage-charges-court-rules|title = Julian Assange can be extradited to US to face espionage charges, court rules|website = ]|date = 10 December 2021}}</ref> | In December 2021, the ] ruled that Assange may be extradited to the US.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/dec/10/julian-assange-can-be-extradited-to-us-to-face-espionage-charges-court-rules|title = Julian Assange can be extradited to US to face espionage charges, court rules|website = ]|date = 10 December 2021}}</ref> | ||

| Line 30: | Line 28: | ||

| Following the 2010 and 2011 Manning leaks, authorities in the US began investigating Assange and WikiLeaks, specifically, a grand jury in Alexandria, Virginia, beginning in 2011.{{Citation needed|date=October 2022}} Assange broke ] to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he was wanted for questioning in connection with an arrest warrant for one charge of unlawful coercion, two charges of sexual molestation, and one charge of rape, and became a fugitive.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Stuart |first=Tessa |last2=Stuart |first2=Tessa |date=2019-04-11 |title=Everything Julian Assange Is Accused of, Explained |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/julian-assange-explainer-819208/ |access-date=2022-10-05 |website=Rolling Stone |language=en-US}}</ref> The ] distanced itself from Assange.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Dorling |first1=Philip |title=Assange felt 'abandoned' by Australian government after letter from Roxon |url=https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/assange-felt-abandoned-by-australian-government-after-letter-from-roxon-20120620-20npj.html|newspaper=] |date=20 June 2012|access-date=13 April 2019|quote=Mr Assange failed last week to persuade the British Supreme Court to reopen his appeal against extradition to Sweden to be questioned about sexual assault allegations}}</ref> | Following the 2010 and 2011 Manning leaks, authorities in the US began investigating Assange and WikiLeaks, specifically, a grand jury in Alexandria, Virginia, beginning in 2011.{{Citation needed|date=October 2022}} Assange broke ] to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he was wanted for questioning in connection with an arrest warrant for one charge of unlawful coercion, two charges of sexual molestation, and one charge of rape, and became a fugitive.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Stuart |first=Tessa |last2=Stuart |first2=Tessa |date=2019-04-11 |title=Everything Julian Assange Is Accused of, Explained |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/julian-assange-explainer-819208/ |access-date=2022-10-05 |website=Rolling Stone |language=en-US}}</ref> The ] distanced itself from Assange.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Dorling |first1=Philip |title=Assange felt 'abandoned' by Australian government after letter from Roxon |url=https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/assange-felt-abandoned-by-australian-government-after-letter-from-roxon-20120620-20npj.html|newspaper=] |date=20 June 2012|access-date=13 April 2019|quote=Mr Assange failed last week to persuade the British Supreme Court to reopen his appeal against extradition to Sweden to be questioned about sexual assault allegations}}</ref> | ||

| He then sought and gained ] from Ecuador, granted by Rafael Correa, after visiting the ].<ref> '']'' (London). 23 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2014.</ref><ref>, ] News, 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.</ref><ref>, ] News, 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.</ref> | He then sought and gained ] from Ecuador, granted by Rafael Correa, after visiting the ].<ref name=":7"> '']'' (London). 23 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2014.</ref><ref name=":6">, ] News, 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.</ref><ref>, ] News, 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.</ref> | ||

| At the same time, an investigation by the ] was going on regarding Assange's release of the Manning documents,<ref name="CarrSomaiya">David Carr and Ravi Somaiya, , '']'', 24 June 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.</ref> and according to court documents dated May 2014, he was still under active and ongoing investigation.<ref>Philip Dorling, '']'', 20 May 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.</ref> A warrant issued to Google by the district court cited several crimes, including espionage, conspiracy to commit espionage, theft or conversion of property belonging to the United States government, violation of the ] and general conspiracy. An indictment continued to remain sealed as of January 2019, although investigations seemed to have intensified as the case neared its statute of limitations.<ref name="tribune2019">{{cite web|url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/ct-chelsea-manning-subpoenaed-julian-assange-investigation-20190301-story.html|title=Chelsea Manning subpoenaed to testify before grand jury in Julian Assange investigation|first1=Rachel|last1=Weiner|first2=Ellen|last2=Nakashima|newspaper=]|date=1 March 2019|access-date=8 March 2019}}</ref> | At the same time, an investigation by the ] was going on regarding Assange's release of the Manning documents,<ref name="CarrSomaiya">David Carr and Ravi Somaiya, , '']'', 24 June 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.</ref> and according to court documents dated May 2014, he was still under active and ongoing investigation.<ref>Philip Dorling, '']'', 20 May 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.</ref> A warrant issued to Google by the district court cited several crimes, including espionage, conspiracy to commit espionage, theft or conversion of property belonging to the United States government, violation of the ] and general conspiracy. An indictment continued to remain sealed as of January 2019, although investigations seemed to have intensified as the case neared its statute of limitations.<ref name="tribune2019">{{cite web|url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/ct-chelsea-manning-subpoenaed-julian-assange-investigation-20190301-story.html|title=Chelsea Manning subpoenaed to testify before grand jury in Julian Assange investigation|first1=Rachel|last1=Weiner|first2=Ellen|last2=Nakashima|newspaper=]|date=1 March 2019|access-date=8 March 2019}}</ref> | ||

| Line 94: | Line 92: | ||

| On 25 March 2020, a London court denied Assange bail, after Judge Vanessa Baraitser rejected his lawyers' argument that his stay in prison would put him at high risk of contracting ] due to his previous respiratory tract infections and a heart problem.<ref name=baildenied>{{cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-britain-assange/wikileaks-founder-julian-assange-denied-bail-by-london-court-idUSKBN21C266|title=Wikileaks founder Julian Assange denied bail by London court|publisher=Reuters|date=25 March 2020|access-date=25 March 2020}}</ref> Judge Baraitser said that Assange's past conduct showed how far he was willing to go to avoid extradition to the United States.<ref name=baildenied /> | On 25 March 2020, a London court denied Assange bail, after Judge Vanessa Baraitser rejected his lawyers' argument that his stay in prison would put him at high risk of contracting ] due to his previous respiratory tract infections and a heart problem.<ref name=baildenied>{{cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-britain-assange/wikileaks-founder-julian-assange-denied-bail-by-london-court-idUSKBN21C266|title=Wikileaks founder Julian Assange denied bail by London court|publisher=Reuters|date=25 March 2020|access-date=25 March 2020}}</ref> Judge Baraitser said that Assange's past conduct showed how far he was willing to go to avoid extradition to the United States.<ref name=baildenied /> | ||

| In late June 2020, the United States Justice Department expanded the indictment against Assange. The new indictment alleged Assange attempted to |

In late June 2020, the United States Justice Department expanded the indictment against Assange. The new indictment alleged Assange attempted to recruit hackers at conferences around the world as far back as 2009, and conspired with hackers including members of LulzSec and Anonymous. The charging document also accused Assange of "gaining unauthorised access to a government computer system of a NATO country in 2010." The indictment also described Assange's alleged efforts to recruit system administrators, Assange and WikiLeaks' role in helping Snowden flee the US, and their use of Snowden as a recruitment tool.<ref name=":8">Milligan, Ellen (29 June 2020). . '']'' via ]. Archived from the on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.</ref><ref name=":9">{{Cite web |title=Julian Assange ‘conspired with Anonymous-affiliated hackers’ |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/6/25/julian-assange-conspired-with-anonymous-affiliated-hackers |access-date=2022-10-05 |website=www.aljazeera.com |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":10">{{Cite web |date=25 June 2020 |title=SECOND SUPERSEDING INDICTMENT |url=https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1289641/download}}</ref><ref name=":11">{{Cite web |last=Tucker |first=Eric |date=2020-06-25 |title='Hacker not journalist': Assange faces fresh allegations in US |url=https://www.smh.com.au/world/north-america/assange-faces-fresh-allegations-in-us-indictment-20200625-p555zs.html |access-date=2022-10-05 |website=The Sydney Morning Herald |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":12">{{Cite web |last=emptywheel |date=2020-06-28 |title=The Government Argues that Edward Snowden Is a Recruiting Tool |url=https://www.emptywheel.net/2020/06/28/the-governments-argument-about-edward-snowden-as-a-recruiting-tool/ |access-date=2022-10-05 |website=] |language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| ===Extradition hearings=== | ===Extradition hearings=== | ||

Revision as of 04:02, 9 October 2022

Arrest of WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange on 11 April 2019This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In 2012, while fighting extradition to Sweden for questioning over sex assault claims, Julian Assange applied for and was granted political asylum by Ecuador and he remained in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London from 2012 until 2019. On 11 April 2019, his asylum was revoked and he was carried out of the Embassy and arrested by the London Metropolitan Police for failing to appear in court. Following his arrest, a US indictment from 2018 was made public accusing Assange of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion. The charge carries a maximum sentence of five years with a possibility of parole.

On 23 May 2019, a US grand jury added 17 espionage charges related to his involvement with Chelsea Manning, making a total of 18 federal charges against Assange in the US. The 18 charges could result in a sentence of up to 175 years in prison. On 25 June 2020 a new indictment was filed, alleging that Assange attempted to recruit hackers and system administrators at conferences around the world as far back as 2009, and conspired with hackers including members of LulzSec and Anonymous. The indictment also described Assange's alleged efforts to recruit system administrators, Assange and WikiLeaks' role in helping Snowden flee the US, and their use of Snowden as a recruitment tool.

In response to the indictment, the New York Times' Editorial Board warned that "The administration has begun well by charging Mr. Assange with an indisputable crime. But there is always a risk with this administration — one that labels the free press as “the enemy of the people” — that the prosecution of Mr. Assange could become an assault on the First Amendment and whistle-blowers."

In December 2021, the High Court of Justice ruled that Assange may be extradited to the US.

Background

Publication of material from Manning

Assange and some of his friends founded WikiLeaks in 2006 and started visiting Europe, Asia, Africa and North America to look for, and publish, secret information concerning companies and governments that they felt should be made public. However, these leaks attracted little interest from law enforcement.

In 2010, Assange was contacted by Chelsea Manning, who gave him classified information containing various military operations conducted by the US government abroad. The material included the Baghdad airstrike of 2007, Granai Airstrike of 2009, the Iraq War Logs, Afghan War Diaries, and the Afghan War Logs, among others. Some of these documents were published by WikiLeaks and leaked to other major media houses including The Guardian between 2010 and 2011.

Critics of the release included Julia Gillard, then Australian Prime Minister, who said the act was illegal, and the vice-president of the United States, Joe Biden, who called him a terrorist. Others, including Brazilian president Luiz da Silva and Ecuadorean president Rafael Correa, supported his actions, while Russian president Dmitry Medvedev said he deserved a Nobel prize for his actions. The Manning leaks also led WikiLeaks and Julian Assange to receive various accolades and awards, but at the same time attracted police investigations.

Criminal investigation and indictment

Following the 2010 and 2011 Manning leaks, authorities in the US began investigating Assange and WikiLeaks, specifically, a grand jury in Alexandria, Virginia, beginning in 2011. Assange broke bail to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he was wanted for questioning in connection with an arrest warrant for one charge of unlawful coercion, two charges of sexual molestation, and one charge of rape, and became a fugitive. The Australian government distanced itself from Assange.

He then sought and gained political asylum from Ecuador, granted by Rafael Correa, after visiting the country's embassy in London.

At the same time, an investigation by the FBI was going on regarding Assange's release of the Manning documents, and according to court documents dated May 2014, he was still under active and ongoing investigation. A warrant issued to Google by the district court cited several crimes, including espionage, conspiracy to commit espionage, theft or conversion of property belonging to the United States government, violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and general conspiracy. An indictment continued to remain sealed as of January 2019, although investigations seemed to have intensified as the case neared its statute of limitations.

Arrest by the Metropolitan Police

After Assange's asylum was revoked, the Ambassador of Ecuador to the UK invited the Metropolitan Police into the embassy on 11 April 2019. Assange was arrested and taken to a central London police station. Assange was carrying Gore Vidal's History of the National Security State during his forcible removal from the embassy and shouted "the UK has no sovereignty" and "the UK must resist this attempt by the Trump administration ... " as five police officers put him into a van. The news of the arrest went viral within minutes and several media outlets reported it as breaking news. President Moreno called Assange a "spoiled brat" in the wake of the arrest.

CNN reported that "British police entered the Ecuadorian Embassy in London... forcibly removing the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange on a US extradition warrant and bringing his seven-year stint there to a dramatic close." At a hearing at Westminster Magistrates' Court a few hours after his arrest, the presiding judge found Assange was guilty of breaching the terms of his bail. On 1 May 2019, Assange was sentenced to 50 weeks in prison.

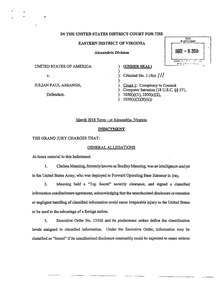

Sealed indictment

In 2012 and 2013, US officials indicated that Assange was not named in a sealed indictment. On 6 March 2018, a federal grand jury for the Eastern District of Virginia issued a sealed indictment against Assange. In November 2018, US prosecutors accidentally revealed that Assange had been indicted under seal in US federal court; the revelation came as a result of an error in a different court filing, unrelated to Assange.

Charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion

On 11 April 2019, the day of Assange's arrest in London, the indictment against him was unsealed. He was charged with conspiracy to commit computer intrusion (i.e. hacking into a government computer), a crime that carries a maximum 5-year sentence . The charges stem from the allegation that Assange conspired and failed to crack a password hash so that Chelsea Manning could use a different username to download classified documents and avoid detection. This allegation had been known since 2011 and was a factor in Manning's trial; the indictment did not reveal any new information about Assange.

Charges under the Espionage Act

On 23 May 2019, Assange was indicted on 17 new charges relating to the Espionage Act of 1917 in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The Espionage Act charges carry a maximum sentence of 170 years in prison. The Obama administration had debated charging Assange under the Espionage Act but decided against it out of fear that it would have a negative effect on investigative journalism and could be unconstitutional. The new charges relate to obtaining and publishing the secret documents. Most of these charges relate to obtaining the secret documents. The three charges related to publication concern documents which revealed the names of sources in dangerous places putting them "at a grave and imminent risk" of harm or detention. The New York Times commented that it and other news organisations obtained the same documents as WikiLeaks, also without government authorisation. It also said it is not clear how WikiLeaks' publications are legally different from other publications of classified information.

Most cases brought under the Espionage Act have been against government employees who accessed sensitive information and leaked it to journalists and others. Prosecuting people for acts related to receiving and publishing information has not previously been tested in court. In 1975, the Justice Department decided after consideration not to charge journalist Seymour Hersh for reporting on US surveillance of the Soviet Union. Two lobbyists for a pro-Israel group were charged in 2005 with receiving and sharing classified information about American policy toward Iran. The charges however did not relate to the publication of the documents and the case was dropped by the Justice Department in 2009 prior to judgement.

Assistant Attorney General John Demers said "Julian Assange is no journalist". The US allegation that Assange's publication of these secrets was illegal was deemed controversial by Australia's Seven News as well as CNN. The Cato Institute also questioned the US government's position which attempts to position Assange as not a journalist. The Associated Press said Assange's indictment presented media freedom issues, as Assange's solicitation and publication of classified information is something journalists routinely do.

Stephen Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, stated that what Assange is accused of doing is factually different from, but legally similar to what professional journalists do. Vladeck also said the Espionage Act charges could provide Assange with an argument against extradition under the US-UK treaty, as there is an exemption in the treaty for political offences. Forbes magazine stated that the US government created an outcry among journalists in its indictment of Assange as the US sought to debate whether Assange was a journalist or not. Suzanne Nossel of PEN America said it was immaterial whether Assange was a journalist or publisher and pointed instead to First Amendment concerns.

Aftermath of his arrest

Indictments and possible extradition to the US

Immediately following the arrest of Assange, the Eastern District of Virginia grand jury unsealed the indictment it had brought against him. According to the indictment, Assange was accused of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion in order to assist Chelsea Manning gain access to privileged information, which he intended to publish on WikiLeaks. This is a less serious charge than those levelled against Manning, and carries a maximum sentence of five years.

Assange was arrested in April, after being carried out of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where he had been living since 2012, avoiding an international arrest warrant, was sentenced to 50 weeks in prison by a British judge on 1 May 2019.

Judge Deborah Taylor said Assange's time in the embassy had cost British taxpayers the equivalent of nearly $21 million, and that he had sought asylum in a "deliberate attempt to delay justice."

Assange offered a written apology in court, claiming that his actions were a response to terrifying circumstances. He said he had been effectively imprisoned in the embassy; two doctors also provided medical evidence of the mental and physical effects of being confined. To which the judge Deborah Taylor said "You were not living under prison conditions, and you could have left at any time to face due process with the rights and protections which the legal system in this country provides".

On 23 May 2019, Assange was indicted, in a superseding indictment, under the Espionage Act of 1917, in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia for offences relating to the publication of diplomatic cables and other sensitive information. The indictment added 17 federal charges to the earlier federal indictment, thus bringing a total of 18 federal criminal charges against Assange from the US federal government with a sentence of up to 175 years in prison. The charges are related to his involvement with Chelsea Manning, a former US Army intelligence analyst who gave Assange classified information concerning matters surrounding the US Defense Department.

On 25 March 2020, a London court denied Assange bail, after Judge Vanessa Baraitser rejected his lawyers' argument that his stay in prison would put him at high risk of contracting COVID-19 due to his previous respiratory tract infections and a heart problem. Judge Baraitser said that Assange's past conduct showed how far he was willing to go to avoid extradition to the United States.

In late June 2020, the United States Justice Department expanded the indictment against Assange. The new indictment alleged Assange attempted to recruit hackers at conferences around the world as far back as 2009, and conspired with hackers including members of LulzSec and Anonymous. The charging document also accused Assange of "gaining unauthorised access to a government computer system of a NATO country in 2010." The indictment also described Assange's alleged efforts to recruit system administrators, Assange and WikiLeaks' role in helping Snowden flee the US, and their use of Snowden as a recruitment tool.

Extradition hearings

On 25 February 2020, one of the barristers representing Assange, Edward Fitzgerald revealed to District Judge Vanessa Baraitser that Dana Rohrabacher, as an emissary of President Donald Trump, had offered Assange a pardon from President Trump, if Assange could offer material identifying the source of email leaks from the Democratic National Committee during 2016.

On 20 April 2022, a British judge formally issued Assange's extradition order. The decision was sent to the UK government, where the Home Secretary Priti Patel was to finalize his transfer to the US. Assange can appeal the decision by judicial review, if it is approved by Patel. On 18 June 2022, Patel approved the decision to extradite Assange in the United States; Assange announced that he would appeal the decision.

Revelations about use of Ecuadorian Embassy

On 15 July 2019, CNN obtained documents from a private Spanish security company, UC Global, which had been performing surveillance on Assange in the Ecuadorian Embassy. CNN said the documents showed that Assange used the embassy as the command centre for WikiLeaks.

Reactions to the indictment

While some US politicians supported the arrest and indictment of Julian Assange, several jurists, politicians, associations, academics and campaigners viewed the arrest of Assange as an attack on freedom of the press and international law. Reporters Without Borders said Assange's arrest could "set a dangerous precedent for journalists, whistle-blowers, and other journalistic sources that the US may wish to pursue in the future." Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, wrote that Assange's prosecution for publishing leaked documents is "a major threat to global media freedom". United Nations rights expert Agnes Callamard said the arrest of Assange exposed him to the risk of serious human rights violations, if extradited to the United States. The yellow vests movement called for Assange's release.

Reactions in the UK and the EU

Dutch senator Tiny Kox (Socialist Party) asked the Council of Europe's commissioner for human rights, Dunja Mijatović, whether the arrest of Assange and his possible extradition to the US were in line with the criteria of the European Convention on Human Rights. In January 2020, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe voted to oppose Assange's extradition to the US.

In 2019, British Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn said that Assange had revealed "evidence of atrocities in Iraq and Afghanistan" and his extradition to the United States "should be opposed by the British government". In February 2020, Corbyn again praised Assange, demanding a halt to the extradition. Prime Minister Boris Johnson responded vaguely with "it’s obvious that the rights of journalists and whistleblowers should be upheld and this government will continue to do that.”

Eva Joly, magistrate and MEP for Europe Ecology–The Greens, said that "the arrest of Julian Assange is an attack on freedom of expression, international law and right to asylum". Sevim Dagdelen, a German Bundestag MP for The Left who specialises in international law and press law, describes Assange's arrest as "an attack on independent journalism" and says that he "is today seriously endangered". Dick Marty, a former state prosecutor of Ticino and rapporteur on the CIA's secret prisons for the Council of Europe, considers the arrest of whistleblowers "very shocking". Several well-known Swiss jurists have asked the Federal Council to grant asylum to the founder of WikiLeaks because he is threatened with extradition to the United States, which in the past "silenced whistleblowers".

In a letter, the two French Unions of Journalists (Syndicat national des journalistes (CGT) [fr]) and (Syndicat national des journalistes (CFDT) [fr]) asked Emmanuel Macron to enforce Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. According them, "Faced with threats to Julian Assange's health and at the risk of seeing him sentenced to life imprisonment, we are saying loud and clear, with the IFJ (Fédération internationale des journalistes) that 'journalism is not a crime'". They add:

Julian Assange denounced in his publications war crimes condemned by the Geneva Convention. Today, he is the one we would like to imprison, we would like to silence. ... We consider this case one of the most serious attacks on the freedom of the press, against public freedoms within the EU. The IFJ, the French unions and their Australian counterparts have launched a motion to seize this serious case the UN Human Rights Council and the European Parliament and the Council of Europe.

WikiLeaks was recognised as a "media organisation" in 2017 by a UK tribunal, contradicting public assertions to the contrary by some US officials, and possibly supporting Assange's efforts to oppose his extradition to the United States.

According to Amnesty International's Massimo Moratti, if extradited to the United States, Assange may face the "risk of serious human rights violations, namely detention conditions, which could violate the prohibition of torture".

Reactions in the US

While some American journalism institutions and bi-partisan support from politicians supported Assange's arrest and indictment, several non-government organisations for press freedom condemned it. Mark Warner, vice chairman of the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, said that Assange was "a dedicated accomplice in efforts to undermine American security". Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham and Senator Joe Manchin also spoke in support of the arrest and indictment.

After Assange's arrest and first indictment, the New York Times' Editorial Board wrote that "The case of Mr. Assange, who got his start as a computer hacker, illuminates the conflict of freedom and harm in the new technologies, and could help draw a sharp line between legitimate journalism and dangerous cybercrime." The Editorial Board also warned that "The administration has begun well by charging Mr. Assange with an indisputable crime. But there is always a risk with this administration — one that labels the free press as “the enemy of the people” — that the prosecution of Mr. Assange could become an assault on the First Amendment and whistle-blowers." The Washington Post's Editorial Board wrote that Assange was "not a free-press hero" or a journalist, and that he was "long overdue for personal accountability."

Frida Ghitis warned that "while Assange is not a journalist, his arrest does present a potential threat to other journalists. One can easily foresee someone like President Donald Trump using the precedent against others reporting information he doesn't like. If a man who claims he is a journalist can be arrested and prosecuted for his work, others could also be charged."

The Associated Press reported that the indictment raised concerns about media freedom, as Assange's solicitation and publication of classified information is a routine job journalists perform. Steve Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, stated that what Assange is accused of doing is factually different from but legally similar to what professional journalists do. Suzanne Nossel of PEN America said it was immaterial if Assange was a journalist or publisher and pointed instead to First Amendment concerns. In a call with reporters, U.S. Attorney Terwilliger said that "Assange is charged for his alleged complicity in illegal acts to obtain or receive voluminous databases of classified information and for agreeing and attempting to obtain classified information through computer hacking. The United States has not charged Assange for passively obtaining or receiving classified information."

The deputy director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, Robert Mahoney, said "With this prosecution of Julian Assange, the US government could set out broad legal arguments about journalists soliciting information or interacting with sources that could have chilling consequences for investigative reporting and the publication of information of public interest." According to Yochai Benkler, a Harvard law professor, the charge sheet contained some "very dangerous elements that pose significant risk to national security reporting. Sections of the indictment are vastly overbroad and could have a significant chilling effect – they ought to be rejected." Carrie DeCell, staff attorney with the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said the charges "risk having a chill on journalism". She added, "Many of the allegations fall absolutely within the first amendment's protections of journalistic activity. That's very troubling to us."

Ben Wizner from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) speculated that if authorities were to prosecute Assange "for violating US secrecy laws would set an especially dangerous precedent for US journalists, who routinely violate foreign secrecy laws to deliver information vital to the public's interest."

NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden and the Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg condemned the indictment. Snowden tweeted that "Assange's critics may cheer, but this is a dark moment for press freedom." Daniel Ellsberg said:

Forty-eight years ago, I was the first journalistic source to be indicted. There have been perhaps a dozen since then, nine under President Obama. But Julian Assange is the first journalist to be indicted. If he is extradited to the U.S. and convicted, he will not be the last. The First Amendment is a pillar of our democracy and this is an assault on it. If freedom of speech is violated to this extent, our republic is in danger. Unauthorized disclosures are the lifeblood of the republic.

According to Ron Paul, Assange should receive the same kind of protections as the mainstream media when it comes to releasing information. He said "In a free society we're supposed to know the truth ... In a society where truth becomes treason, then we're in big trouble. And now, people who are revealing the truth are getting into trouble for it." He added "This is media, isn't it? I mean, why don't we prosecute The New York Times or anybody that releases this?"

Ecuadorian president Lenín Moreno, the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, the British Foreign Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, U.S. Senators Mark Warner, Lindsey Graham and Senator Joe Manchin, Hillary Clinton campaign advisor Neera Tanden, and British Prime Minister Theresa May, who commented that "no one is above the law," supported the arrest. Alternatively, it has been asserted that such a move would be a threat to freedom of speech as protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. This view is held by Edward Snowden, Rafael Correa, Chelsea Manning, Jeremy Corbyn, Kenneth Roth of Human Rights Watch, and Glenn Greenwald, who said "it's the criminalization of journalism".

The president of the Center for American Progress and former Obama aide Neera Tanden also welcomed the arrest and condemned Assange's leftist supporters, tweeting that "the Assange cultists are the worst. Assange was the agent of a proto-fascist state, Russia, to undermine democracy. That is fascist behaviour. Anyone on the left should abhor what he did."

According to the editorial in The Times "the prosecution of Mr Assange could become an assault on the First Amendment and whistle-blowers".

The Reporters Without Borders said Assange's arrest could "set a dangerous precedent for journalists, whistle-blowers, and other journalistic sources that the US may wish to pursue in the future." Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, wrote that Assange's prosecution for publishing leaked documents is "a major threat to global media freedom". Freedom of the Press Foundation said: "Whether or not you like Assange, the charge against him is a serious press freedom threat and should be vigorously protested by all those who care about the first amendment."

The yellow vests movement called for Assange's release.

Reactions in Australia

In October 2019, former deputy prime minister Barnaby Joyce (National Party of Australia) called for the federal government to take action to stop Assange being extradited from the United Kingdom to the US. Later in October, the cross-party Bring Assange Home Parliamentary Working Group was established. Its co-chairs are independent Andrew Wilkie and Liberal National MP George Christensen. Its members include Greens Richard Di Natale, Adam Bandt and Peter Whish-Wilson, Centre Alliance MPs Rebekha Sharkie and Rex Patrick and independent Zali Steggall.

In the lead up to an extradition hearing on 1 June 2020, more than 100 politicians, journalists, lawyers and human rights activists from Australia wrote to Foreign Minister Marise Payne, asking her to make urgent representations to the UK government to have Assange released on bail due to his ill-health.

Other reactions

Former Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa condemned Assange's arrest. Former Bolivian President Evo Morales also condemned it. Maria Zakharova, spokesperson for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, condemned the indictment. The ex-President of Brazil Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said that "Humanity should demand its freedom. Instead of being imprisoned he should be treated like a hero", during his visit in Genebra.

Ecuadorean president Lenín Moreno said in a video posted on Twitter that he "requested Great Britain to guarantee that Mr Assange would not be extradited to a country where he could face torture or the death penalty. The British government has confirmed it in writing, in accordance with its own rules." On 14 April 2019 Moreno stated in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian that no other nation influenced his government's decision to revoke Assange's asylum in the embassy and that Assange did in fact use facilities in the embassy "to interfere in processes of other states." Moreno also stated "we can not allow our house, the house that opened its doors, to become a centre for spying" and noted that Assange also had poor hygiene. Moreno further stated "We never tried to expel Assange, as some political actors want everyone to believe. Given the constant violations of protocols and threats, political asylum became untenable." On 11 April 2019, Moreno described Assange as a "bad mannered" guest who physically assaulted embassy security guards.

Independent United Nations rights experts such as Agnes Callamard said "the arrest of WikiLeaks co-founder Julian Assange by police in the United Kingdom, after the Ecuadorian Government decided to stop granting him asylum in their London embassy, exposed him to the risk of serious human rights violations, if extradited to the United States".

On Assange's birthday in July 2020, 40 organizations, including the International Federation of Journalists, the National Union of Journalists, the National Lawyers Guild, the International Association of Democratic Lawyers, the Centre for Investigative Journalism and the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters, wrote an open letter demanding that Assange be released.

Widespread criticism from the news media and other public advocates ensued following Assange's arrest on Espionage charges. Multiple organisations and journalists criticised Assange's arrest as a journalist citing first amendment claims.

- The New York Times stated: "Julian Assange, the WikiLeaks leader, was indicted on 17 counts of violating the Espionage Act for his role in obtaining and publishing secret military and diplomatic documents in 2010, the Justice Department announced on Thursday — a novel case that raises profound First Amendment issues."

- The Guardian said: "By bringing new charges against the WikiLeaks founder, the Trump administration has challenged the first amendment"

- HuffPost said: "The charges against the WikiLeaks founder bring up huge First Amendment issues."

- The Nation said: "The Indictment of Julian Assange Is a Threat to Press Freedom."

- The American Civil Liberties Union said: "For the first time in the history of our country, the government has brought criminal charges under the Espionage Act against a publisher for the publication of truthful information. This is a direct assault on the First Amendment."

- Jonathan Turley described the Assange indictment under the Espionage Act of 1917 as "the most important press freedom case in the US in 300 years".

See also

References

- ^ "Julian Assange: Ecuador grants WikiLeaks founder asylum", BBC News, 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Julian Assange asylum bid: ambassador flies into Ecuador for talks with President Correa". The Daily Telegraph (London). 23 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Julian Assange can be extradited to US to face espionage charges, court rules". TheGuardian.com. 10 December 2021.

- Megerian, Chris; Boyle, Christina; Wilber, Del Quentin (11 April 2019). "WikiLeaks' Julian Assange faces U.S. hacking charge after dramatic arrest in London". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Sullivan, Eileen; Pérez-Peña, Richard (11 April 2019). "Julian Assange Charged by U.S. With Conspiracy to Hack a Government Computer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Becket, Stefan (23 May 2019). "Julian Assange indictment: Julian Assange hit with 18 federal charges today, related to WikiLeaks' release of Chelsea Manning docs". CBS News.

- ^ "Julian Assange: US hits WikiLeaks founder with 18 new charges, receiving and publishing classified information". News.com.au. 24 May 2019.

- ^ Milligan, Ellen (29 June 2020). Julian Assange Lawyers Say New U.S. Indictment Could Derail Extradition. MSN News via Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Julian Assange 'conspired with Anonymous-affiliated hackers'". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "SECOND SUPERSEDING INDICTMENT". 25 June 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Eric (25 June 2020). "'Hacker not journalist': Assange faces fresh allegations in US". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ emptywheel (28 June 2020). "The Government Argues that Edward Snowden Is a Recruiting Tool". Emptywheel. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Board, The Editorial (11 April 2019). "Opinion | 'Curious Eyes Never Run Dry'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "Wikileaks defends Iraq war leaks". BBC. 23 October 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Davies, Nick; Leigh, David (25 July 2010). "Afghanistan war logs: Massive leak of secret files exposes truth of occupation". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "WikiLeaks acting illegally, says Gillard," Sydney Morning Herald, 2 December 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- Ewen MacAskill, "Julian Assange like a hi-tech terrorist, says Joe Biden," The Guardian, 20 December 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- "When Wikileaks founder Julian Assange met Ecuadorean president Rafael Correa". The Daily Telegraph. 20 June 2012.

- 'Russia: Julian Assange deserves a Nobel Prize' ," The Jerusalem Post, 12 November 2010.

- Joel Gunter, "Julian Assange wins Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism," Journalism.co.uk, 2 June 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- Stuart, Tessa; Stuart, Tessa (11 April 2019). "Everything Julian Assange Is Accused of, Explained". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- Dorling, Philip (20 June 2012). "Assange felt 'abandoned' by Australian government after letter from Roxon". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

Mr Assange failed last week to persuade the British Supreme Court to reopen his appeal against extradition to Sweden to be questioned about sexual assault allegations

- "U.K.: WikiLeaks' Assange won't be allowed to leave", CBS News, 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- David Carr and Ravi Somaiya, "Assange, back in news, never left U.S. radar", The New York Times, 24 June 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Philip Dorling, "Assange targeted by FBI probe, US court documents reveal," The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 May 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Weiner, Rachel; Nakashima, Ellen (1 March 2019). "Chelsea Manning subpoenaed to testify before grand jury in Julian Assange investigation". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Wikileaks co-founder Julian Assange arrested". BBC. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Tobitt, Charlotte (11 April 2019). "RT's video agency Ruptly beats UK media to Julian Assange footage". Press Gazette. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Julian Assange, WikiLeaks founder, was holding Gore Vidal book during arrest". USA Today. 11 April 2019.

- "Why Ecuador evicted 'spoiled brat' Assange from embassy". NBC News. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Julian Assange arrested in London: Live updates - CNN". 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Murphy, Simon (11 April 2019). "Assange branded a 'narcissist' by judge who found him guilty". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Quinn, Ben (1 May 2019). "Julian Assange jailed for 50 weeks for breaching bail in 2012". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Mark Hosenball, "Despite Assange claims, U.S. has no current case against him", Reuters, 22 August 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Sari Horwitz, "Assange not under sealed indictment, U.S. officials say", The Washington Post, 18 November 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Charlie Savage, Adam Goldman & Eileen Sullivan,Julian Assange Arrested in London as U.S. Unseals Hacking Conspiracy Indictment, The New York Times (11 April 2019).

-

Charlie Savage; Adam Goldman; Michael S. Schmidt (16 November 2018). "Assange Is Secretly Charged in U.S., Prosecutors Mistakenly Reveal". The New York Times. Washington DC. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

Mr. Hughes, the terrorism expert, who is the deputy director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, posted a screenshot of the court filing on Twitter shortly after The Wall Street Journal reported on Thursday that the Justice Department was preparing to prosecute Mr. Assange.

-

Jack Stripling (16 November 2018). "How a George Washington U. Researcher Stumbled Across a Huge Government Secret". the Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

But the Journal's report made clear that Hughes had stumbled upon something quite remarkable: a major government secret that was hidden in plain sight.

- "Julian Assange charged in US: WikiLeaks". Agence-France Presse. 16 November 2018.

- Hosenball, Mark (16 November 2018). "U.S. prosecutors get indictment against Wikileaks' Assange: court..." Reuters.

- Kevin Poulsen; Spencer Ackerman (16 November 2018). "Julian Assange 'Has Been Charged,' According to Justice Department Filing". Daily Beast.

- Megerian, Chris; Boyle, Christina; Wilber, Del Quentin (11 April 2019). "WikiLeaks' Julian Assange faces U.S. hacking charge after dramatic arrest in London". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Sullivan, Eileen; Pérez-Peña, Richard (11 April 2019). "Julian Assange Charged by U.S. With Conspiracy to Hack a Government Computer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "WikiLeaks Founder Charged in Computer Hacking Conspiracy". U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Virginia. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn; Lee, Micah (12 April 2019). "The U.S. Government's Indictment of Julian Assange Poses Grave Threats to Press Freedoms". The Intercept. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Gerstein, Josh. "Defense: Manning was 'overcharged'". POLITICO. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Gurman, Sadie; Viswanatha, Aruna; Volz, Dustin (23 May 2019). "WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange Charged With 17 New Counts". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "US charges WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange with violating Espionage Act, threatening him with up to 170 years in jail". South China Morning Post. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (23 May 2019). "Assange Indicted Under Espionage Act, Raising First Amendment Issues". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ "WikiLeaks founder indicted on criminal charges". CNN Newsource. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Tillman, Zoe (23 May 2019). "The New Charges Against Julian Assange Are Unprecedented. Press Freedom Groups Say They're A Threat To All Journalists". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ZHAO, CHRISTINA (23 May 2019). "'JULIAN ASSANGE IS NO JOURNALIST': WIKILEAKS FOUNDER INDICTED ON 17 NEW CHARGES UNDER ESPIONAGE ACT BY U.S." Spiegel. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Jarrett, Laura (23 May 2019). "Julian Assange is facing new charges under the Espionage Act". 7news. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Carpenter, Ted Galen (5 July 2019). "Julian Assange and the Real War on the Free Press". Cato. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "New charges were filed Thursday against the WikiLeaks founder". Associated Press. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Barrett, Devlin (23 May 2019). "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange charged with violating Espionage Act". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Sandler, Rachel (23 May 2019). "Free Speech Outcry Grows After Assange Indictment". Forbes. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- KENEALLY, MEGHAN (24 May 2019). "New charges against Julian Assange raise concerns about ripple effects on press freedom". ABC News. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Sullivan, Eileen; Pérez-Peña, Richard (11 April 2019). "Julian Assange Charged by U.S. With Conspiracy to Hack a Government Computer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Ingber, Sasha (May 2019). "British Judge Sentences Julian Assange To 50 Weeks In Prison". Npr.org. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Savage, Charlie; Goldman, Adam (23 May 2019). "Assange Indicted Under Espionage Act, Raising First Amendment Issues". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "U.S. Officials File New Charges Against WikiLeaks' Julian Assange". NPR. 24 May 2019.

- "Julian Assange charged with violating Espionage Act in 18-count indictment for WikiLeaks disclosures". ABC News.

- "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange charged with espionage". Sydney Morning Herald. AP, The Washington Post. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Wikileaks founder Julian Assange denied bail by London court". Reuters. 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Trump offered to pardon Assange if he denied Russia helped leak Democrats' emails: lawyer". Reuters. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Isikoff, Michael (20 February 2020). "Rohrabacher confirms he offered Trump pardon to Assange for proof Russia didn't hack DNC email". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Julian Assange extradition order issued by London court, moving WikiLeaks founder closer to US transfer". CNN. 20 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- "UK judge sends extradition case of Wikileaks' Assange to interior minister Patel". Reuters. 20 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- Maguire, Amy; Cullen, Holly (18 June 2022). "UK government orders the extradition of Julian Assange to the US, but that is not the end of the matter". The Conversation.

- "Exclusive: Security reports reveal how Assange turned an embassy into a command post for election meddling". CNN. 15 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Les inculpations contre Julian Assange sont sans précédent, effrayantes, et un coup porté à la liberté de la presse". Le Monde.fr. 24 May 2019 – via Le Monde.

- Opsahl, David Greene and Kurt (24 May 2019). "The Government's Indictment of Julian Assange Poses a Clear and Present Danger to Journalism, the Freedom of the Press, and Freedom of Speech". Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (12 April 2019). "Julian Assange's charges are a direct assault on press freedom, experts warn". The Guardian.

- ^ "Wikileaks co-founder Julian Assange arrested". BBC News. BBC. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "The Assange prosecution threatens modern journalism". The Guardian. 12 April 2019.

- "UN experts warn Assange arrest exposes him to risk of serious human rights violations". UN News. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "Quelque 23.600 gilets jaunes en France, Paris "capitale de l'émeute" le 1er mai?". 7sur7.be. 27 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "VIDÉO – A Paris, les Gilets jaunes ont fait la tournée des médias". LCI (in French). 27 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Liabot, Thomas (2 May 2019). "A Londres, Maxime Nicolle et des Gilets jaunes réclament la libération de Julian Assange". Le Journal du Dimanche. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "La Convention européenne des droits de l'homme peut-elle empêcher l'extradition de Julian Assange vers les États-Unis ?". L'Humanité (in French). 12 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Quinn, Ben (28 January 2020). "Human rights report to oppose extradition of Julian Assange to US". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Merrick, Rob (12 February 2020). "Jeremy Corbyn praises Julian Assange and calls for extradition to US to be halted". Independent.

- Colson, Thomas (12 February 2020). "Boris Johnson threatens to rip up 'unbalanced' extradition treaty with the US after Trump refuses to extradite a diplomat's wife accused of killing a British teenager". Business Insider.

- "VIDEO. Eva Joly : "l'arrestation de Julian Assange est une attaque à la liberté de la presse"". Franceinfo (in French). 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Lutter contre l'extradition d'Assange, c'est lutter pour la liberté de la presse". L'Humanité (in French). 12 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- "Des parlementaires soutiennent Assange à Londres". 24 Heures (Fr) (in French). 15 April 2019. ISSN 1424-4039. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ""Je suis choqué. Assange n'a fait que dire la vérité", clame Dick Marty". rts.ch (in French). 11 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- "Dick Marty: "Assange ha solo detto la verità". In Ecuador un nuovo arresto" (in Italian). 12 April 2019.

- "Des juristes suisses de renom veulent que la Suisse accordent l'asile à Julian Assange, fondateur de Wikileaks". lenouvelliste.ch (in French). Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Des juristes appellent à donner asile à Assange". Le Matin. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "Le cas de Julian Assange constitue une inquiétante violation de la liberté de la presse (communiqué intersyndical)". Acrimed. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Assange hacking charge limits free speech defense: legal experts". Reuters. 11 April 2019 – via reuters.com.

- MacAskill, Ewen (14 December 2017). "WikiLeaks recognised as a 'media organisation' by UK tribunal". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "WikiLeaks called 'media organization' by U.K. tribunal, potentially complicating extradition efforts". The Washington Times.

- Maurizi, Stefania (14 December 2017). "London Tribunal dismisses la Repubblica's appeal to access the full file of Julian Assange". La Repubblica. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "UK's Labour Party calls for PM to prevent Assange's extradition". Al-Jazeera. 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Opinion | Julian Assange is not a free-press hero. And he is long overdue for personal accountability". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Morgan Chalfant, Olivia Beavers and Jacqueline Thomsen (12 April 2019). "Julian Assange: Five things to know about the legal case against him". The Hill. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- "Julian Assange: Truth teller or criminal?". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "World reacts to arrest of WikiLeaks founder of Julian Assange". The CEO Magazine. 12 April 2019.

- ^ Raju, Manu; Stracqualursi, Veronica (11 April 2019). "What US senators are saying about Assange's arrest". CNN. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- Ghitis, Frida (11 April 2019). "Julian Assange is an activist, not a journalist". CNN. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- "New charges were filed Thursday against the WikiLeaks founder". Associated Press. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Barrett, Devlin (23 May 2019). "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange charged with violating Espionage Act". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Keneally, Meghan (24 May 2019). "New charges against Julian Assange raise concerns about ripple effects on press freedom". ABC News. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Julian Assange hit with 18 federal charges in new indictment". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Oprysko, Caitlin; Cheney, Kyle (11 April 2019). "WikiLeaks' Assange arrested on U.S. charges he helped hack Pentagon computers". Politico.

- "Julian Assange arrested after U.S. extradition request, charged with hacking government computer". CBC News. 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Edward Snowden, Rafael Correa Condemn Julian Assange Arrest: 'This Is a Dark Moment for Press Freedom'". Newsweek. 11 April 2019.

- "Daniel Ellsberg on Assange Arrest: The Beginning of the End For Press Freedom". The Real News. 11 April 2019.

- "Factbox: Reaction to arrest of Julian Assange in London". Reuters. 11 April 2019.

- Bernstein, Dennis J. (23 April 2019). "Daniel Ellsberg Speaks Out on the Arrest of Julian Assange". Progressive.org.

- "Daniel Ellsberg On Assange Arrest: The Beginning of the End For Press Freedom" – via YouTube.

- "Ron Paul Defends WikiLeaks Founder's Rights". CBS News. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Julian Assange's arrest draws fierce international reaction". Fox News Channel. 11 April 2019.

- ^ "World reacts to arrest of WikiLeaks founder of Julian Assange". The CEO Magazine. 12 April 2019.

- "The Assange prosecution threatens modern journalism". The Guardian. 12 April 2019.

- Cassidy, John (12 April 2019). "The indictment of Julian Assange is a threat to journalism". The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "VIDÉO - A Paris, les Gilets jaunes ont fait la tournée des médias". LCI (in French). 27 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Davis, Samuel; Stephen, Adam (29 October 2019). "Julian Assange in 'a crazy situation', set to receive request for a visit from George Christensen". ABC News. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Foreign minister urged to intervene in Assange's US extradition proceedings". ABC Radio National. ABC News. 1 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Times, The Moscow (11 April 2019). "Russian Officials Condemn Julian Assange's Arrest in London". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "Lula se reúne com o pai de Julian Assange, o fundador do WikiLeaks" [Lula meets with Julian Assange's father, the founder of WikiLeaks] (in Brazilian Portuguese). 6 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Qualquer um que se importa com a democracia deveria estar se reunindo para apoiar Julian Assange" [Anyone who cares about democracy should be gathering to support Julian Assange]. Agência Pública (in Brazilian Portuguese). 7 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "UK pledges it won't send Assange to country with death penalty: Ecuador". Reuters. 11 April 2019.

- ^ editor, Patrick Wintour Diplomatic (14 April 2019). "Assange tried to use embassy as 'centre for spying', says Ecuador's Moreno". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Ecuador says Assange used embassy to spy". Bbc.com. 15 April 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "'Spoiled Brat' Julian Assange Hit Embassy Guards, Ecuador Says". Bloomberg.com. 4 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "'Spoiled Brat' Julian Assange Hit Embassy Guards, Ecuador Says". Msn.com. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "UN experts warn Assange arrest exposes him to risk of serious human rights violations". UN News. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Forty rights groups call on the UK to release Julian Assange". Reporters Without Borders. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Jones, Alan (3 July 2020). "40 rights groups call for Assange's immediate release". Belfasttelegraph. Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Government faces fresh calls to release Assange as he spends his 49th birthday behind bars". Morning Star. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Assange Indicted Under Espionage Act, Raising First Amendment Issues". NYT. 23 May 2019.

- "Indicting a journalist? What the new charges against Julian Assange mean for free speech". The Guardian. 23 May 2019.

- "What Julian Assange's Arrest Means For Freedom Of The Press". Huffington Post. 23 May 2019.

- "The Indictment of Julian Assange Is a Threat to Press Freedom". The Nation. 23 May 2019.

- "First time in history". The ACLU. 23 May 2019.

- Turley, Jonathan (24 May 2019). "Viewpoint: What Assange charges could mean for press freedom". BBC. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

External links

Quotations related to Julian Assange at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Julian Assange at Wikiquote Media related to Julian Assange at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Julian Assange at Wikimedia Commons