| Revision as of 16:07, 30 September 2020 editNardog (talk | contribs)Edit filter helpers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors82,065 editsm →top: fixing Italian IPA per consensusTag: AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:03, 24 August 2024 edit undoMichael Bednarek (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users85,088 editsm corrected wl for Natalia Macfarren. | ||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 23 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description| |

{{Short description|Tenor aria from Verdi's opera Rigoletto}} | ||

| {{For|the 1942 Italian film|The Lady Is Fickle}} | {{For|the 1942 Italian film|The Lady Is Fickle}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2020}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2020}} | ||

| "'''{{Lang|it|La donna è mobile|italic=no}}'''" ({{IPA |

"'''{{Lang|it|La donna è mobile|italic=no}}'''" ({{IPA|it|la ˈdɔnna ˌɛ mˈmɔːbile|pron}}; "Woman is fickle") is the Duke of Mantua's ] from the beginning of ] of ]'s ] '']'' (1851). The canzone is famous as a showcase for ]s. ]'s performance of the ] ] at the opera's 1851 premiere was hailed as the highlight of the evening. Before the opera's first public performance (in Venice), the aria was rehearsed under tight secrecy,<ref name=Downes /> a necessary precaution, as "{{Lang|it|La donna è mobile|italic=no}}" proved to be incredibly catchy and soon after the aria's first public performance, it became popular to sing among Venetian ]. | ||

| As the opera progresses, the ] of the tune in the following scenes contributes to Rigoletto's confusion as he realizes from the sound of the Duke's lively voice coming from the tavern (offstage) that the body in the sack over which he had grimly triumphed was not that of the Duke after all |

As the opera progresses, the ] of the tune in the following scenes contributes to Rigoletto's confusion as he realizes from the sound of the Duke's lively voice coming from the tavern (offstage) that the body in the sack over which he had grimly triumphed was not that of the Duke after all; Rigoletto had paid Sparafucile, an assassin, to kill the Duke, but Sparafucile had deceived Rigoletto by indiscriminately killing Gilda, Rigoletto's beloved daughter, instead.<ref>, OperaGlass, ]</ref> | ||

| ==Music== | ==Music== | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| The aria is in the ] of ] with a ] of 3/8 and a ] mark of ''allegretto''. The ] extends from ] to A{{music|#}}{{sub|4}} with a ] from F{{music|#}}{{sub|3}} to F{{music|#}}{{sub|4}}. Eight ] form the orchestral introduction, followed by a one-bar general rest. Each verse and the refrain covers eight bars; the whole aria is 87 bars long. | The aria is in the ] of ] with a ] of 3/8 and a ] mark of ''allegretto''. The ] extends from ] to A{{music|#}}{{sub|4}} with a ] from F{{music|#}}{{sub|3}} to F{{music|#}}{{sub|4}}. Eight ] form the orchestral introduction, followed by a one-bar general rest. Each verse and the refrain covers eight bars; the whole aria is 87 bars long. | ||

| The almost comical-sounding ] of "{{Lang|it|La donna è mobile|italic=no}}" is introduced immediately. The theme is repeated several times in the approximately two to three minutes it takes to perform the aria, but with the important—and obvious—omission of the last bar. This has the effect of driving the music forward as it creates the impression of being incomplete and unresolved, which it is, ending not on the ] (B) or ] (F{{music|#}}) but on the ] (G{{music|#}}). Once the Duke has finished singing, however, the theme is once again repeated; |

The almost comical-sounding ] of "{{Lang|it|La donna è mobile|italic=no}}" is introduced immediately. The theme is repeated several times in the approximately two to three minutes it takes to perform the aria, but with the important—and obvious—omission of the last bar. This has the effect of driving the music forward as it creates the impression of being incomplete and unresolved, which it is, ending not on the ] (B) or ] (F{{music|#}}) but on the ] (G{{music|#}}). Once the Duke has finished singing, however, the theme is once again repeated; this time, it includes the last—and conclusive—bar and finally resolves to the tonic of ]. The song is in ] with an orchestral ]. | ||

| ==Libretto== | ==Libretto== | ||

| The lyrics are based on a phrase by King ], {{lang|fr|]}} , that he, deceived by one of his numerous mistresses, reputedly engraved on a window pane. ] used this phrase verbatim in his play, '']'', on which ''Rigoletto'' is based.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.lalanguefrancaise.com/proverbes/souvent-femme-varie-bien-fol-qui-s-y-fie|title=« Souvent femme varie, bien fol qui s'y fie » : signification et origine du proverbe|language=fr|author=Sylvie Brunet|date=8 September 2021|access-date=14 July 2023}}</ref> ] depicted in an 1804 oil painting Francis engraving the lines.<ref>] ]: '']'', (1804)</ref> | |||

| <poem lang="it" style="float:left;"> | <poem lang="it" style="float:left;"> | ||

| La donna è mobile | La donna è mobile | ||

| Line 49: | Line 50: | ||

| Qual piuma al vento, | Qual piuma al vento, | ||

| muta d'accento | muta d'accento | ||

| e di pensier'!<ref name=vs>{{Cite book|url=http://www.dlib.indiana.edu/variations/scores/bhr8278/large/sco30173.html|title=Rigoletto|others=piano vocal score, Italian/English|pages=173ff|first1=Francesco Maria|last1=Piave| |

e di pensier'!<ref name=vs>{{Cite book|url=http://www.dlib.indiana.edu/variations/scores/bhr8278/large/sco30173.html|title=Rigoletto|others=piano vocal score, Italian/English|pages=173ff|first1=Francesco Maria|last1=Piave|author-link1=Francesco Maria Piave|first2=Giuseppe|last2=Verdi|author-link2=Giuseppe Verdi|publisher=]|location=New York|year=c. 1930|translator=]}}</ref></poem> | ||

| <poem style="margin-left:2em; float:left;"> | <poem style="margin-left:2em; float:left;"> | ||

| Woman is flighty. | Woman is flighty. | ||

| Line 118: | Line 119: | ||

| ==Popular culture== | ==Popular culture== | ||

| The tune has been used in popular culture for a long time and for many occasions and purposes. Verdi knew that he had written a |

The tune has been used in popular culture for a long time and for many occasions and purposes. Verdi knew that he had written a catchy tune, so he provided the score to the singer at the premiere, ], only shortly before the premiere and had him swear not to sing or whistle the song outside rehearsals.<ref name=Downes>{{cite book|last=Downes|first=Olin|author-link=Olin Downes|date=September 1918|title=The Lure of Music|url=https://archive.org/stream/lureofmusicdepic00down#page/38/mode/2up|location=New York|publisher=Harper & Brothers|page=38|via=]}}</ref> And indeed, people sang the tune the next day in the streets. Early on, it became a ] staple and was later used extensively in television advertisements.<ref> by Carrie Seidman, '']'', 18 October 2012</ref> Football fans chanted new words to the tune of the melody.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/tales-from-the-terraces-the-chants-of-a-lifetime-5336050.html|title=Tales from the terraces: The chants of a lifetime|author=Stan Hey|newspaper=]|date=21 April 2006|access-date=27 December 2016}}</ref> When all of Italy was under lockdown due to the ], a video of opera singer Maurizio Marchini performing "La donna è mobile" and other arias and songs from his balcony in Florence went viral.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.lanazione.it/firenze/cronaca/tenore-canta-terrazzo-1.5112923|title=Dal balcone di Gavinana al mondo: così il tenore conquista la città|author=Rossella Conte|language=it|date=18 April 2020|work=]|access-date=19 April 2022}}</ref> | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 125: | Line 126: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|La donna è mobile}} | {{Commons category|La donna è mobile}} | ||

| *{{YouTube|8A3zetSuYRg|"La donna è mobile"}}; ] in ]'s 1982 film ''Rigoletto'' |

*{{YouTube|8A3zetSuYRg|"La donna è mobile"}}; ] in ]'s 1982 film ''Rigoletto'' | ||

| *{{YouTube|Q2mMPz_a4vY|Combined performance|link=no}}, Pavarotti, ], ], ], ], 9 April 1994 ] benefit concert | |||

| *, translated by Randy Garrou, Aria Database | *, translated by Randy Garrou, Aria Database | ||

| *], ] | *], ] | ||

| *{{YouTube|_kmr5IlUAhI|"La donna è mobile" – Explained}} | *{{YouTube|_kmr5IlUAhI|"La donna è mobile" – Explained (7 mins)|link=no}} | ||

| {{Rigoletto}} | {{Rigoletto|state=expanded}} | ||

| {{Giuseppe Verdi}} | {{Giuseppe Verdi}} | ||

| {{Portal bar|Opera}} | {{Portal bar|Opera}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Donna e mobile, La}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Donna e mobile, La}} | ||

| Line 140: | Line 143: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:03, 24 August 2024

Tenor aria from Verdi's opera Rigoletto For the 1942 Italian film, see The Lady Is Fickle.

"La donna è mobile" (pronounced [la ˈdɔnna ˌɛ mˈmɔːbile]; "Woman is fickle") is the Duke of Mantua's canzone from the beginning of act 3 of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Rigoletto (1851). The canzone is famous as a showcase for tenors. Raffaele Mirate's performance of the bravura aria at the opera's 1851 premiere was hailed as the highlight of the evening. Before the opera's first public performance (in Venice), the aria was rehearsed under tight secrecy, a necessary precaution, as "La donna è mobile" proved to be incredibly catchy and soon after the aria's first public performance, it became popular to sing among Venetian gondoliers.

As the opera progresses, the reprise of the tune in the following scenes contributes to Rigoletto's confusion as he realizes from the sound of the Duke's lively voice coming from the tavern (offstage) that the body in the sack over which he had grimly triumphed was not that of the Duke after all; Rigoletto had paid Sparafucile, an assassin, to kill the Duke, but Sparafucile had deceived Rigoletto by indiscriminately killing Gilda, Rigoletto's beloved daughter, instead.

Music

|

Problems playing this file? See media help.

"La donna è mobile" (2:42)

Javier Camarena, Gran Teatre del Liceu (2017)

"La donna è mobile" (2:42)

Javier Camarena, Gran Teatre del Liceu (2017)

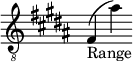

The aria is in the key of B major with a time signature of 3/8 and a tempo mark of allegretto. The vocal range extends from F♯3 to A♯4 with a tessitura from F♯3 to F♯4. Eight bars form the orchestral introduction, followed by a one-bar general rest. Each verse and the refrain covers eight bars; the whole aria is 87 bars long.

The almost comical-sounding theme of "La donna è mobile" is introduced immediately. The theme is repeated several times in the approximately two to three minutes it takes to perform the aria, but with the important—and obvious—omission of the last bar. This has the effect of driving the music forward as it creates the impression of being incomplete and unresolved, which it is, ending not on the tonic (B) or dominant (F♯) but on the submediant (G♯). Once the Duke has finished singing, however, the theme is once again repeated; this time, it includes the last—and conclusive—bar and finally resolves to the tonic of B major. The song is in strophic form with an orchestral ritornello.

Libretto

The lyrics are based on a phrase by King Francis I of France, Souvent femme varie, bien fol qui s'y fie. , that he, deceived by one of his numerous mistresses, reputedly engraved on a window pane. Victor Hugo used this phrase verbatim in his play, Le roi s'amuse, on which Rigoletto is based. Fleury François Richard depicted in an 1804 oil painting Francis engraving the lines.

La donna è mobile

Qual piuma al vento,

muta d'accento

e di pensiero.

Sempre un amabile,

leggiadro viso,

in pianto o in riso,

è menzognero.

Refrain

La donna è mobil'.

Qual piuma al vento,

muta d'accento

e di pensier'!

È sempre misero

chi a lei s'affida,

chi le confida

mal cauto il cuore!

Pur mai non sentesi

felice appieno

chi su quel seno

non liba amore!

Refrain

La donna è mobil'

Qual piuma al vento,

muta d'accento

e di pensier'!

Woman is flighty.

Like a feather in the wind,

she changes in voice

and in thought.

Always a lovely,

pretty face,

in tears or in laughter,

it is untrue.

Refrain

Woman is fickle.

Like a feather in the wind,

she changes her words

and her thoughts!

Always miserable

is he who trusts her,

he who confides in her

his unwary heart!

Yet one never feels

fully happy

who from that bosom

does not drink love!

Refrain

Woman is fickle.

Like a feather in the wind,

she changes her words,

and her thoughts!

Poetic adaptation

Plume in the summerwind

Waywardly playing

Ne'er one way swaying

Each whim obeying;

Thus heart of womankind

Ev'ry way bendeth,

Woe who dependeth

On joy she spendeth!

Refrain

Yes, heart of woman

Ev'ry way bendeth

Woe who dependeth

On joy she spends.

Sorrow and misery

Follow her smiling,

Fond hearts beguiling,

falsehood assoiling!

Yet all felicity

Is her bestowing,

No joy worth knowing

Is there but wooing.

Refrain

Yes, heart of woman

Ev'ry way bendeth

Woe who dependeth

On joy she spends.

Popular culture

The tune has been used in popular culture for a long time and for many occasions and purposes. Verdi knew that he had written a catchy tune, so he provided the score to the singer at the premiere, Raffaele Mirate, only shortly before the premiere and had him swear not to sing or whistle the song outside rehearsals. And indeed, people sang the tune the next day in the streets. Early on, it became a barrel organ staple and was later used extensively in television advertisements. Football fans chanted new words to the tune of the melody. When all of Italy was under lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a video of opera singer Maurizio Marchini performing "La donna è mobile" and other arias and songs from his balcony in Florence went viral.

References

- ^ Downes, Olin (September 1918). The Lure of Music. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 38 – via Internet Archive.

- Rigoletto synopsis, OperaGlass, Stanford University

- Sylvie Brunet (8 September 2021). "« Souvent femme varie, bien fol qui s'y fie » : signification et origine du proverbe" (in French). Retrieved 14 July 2023.

-

Fleury François Richard: François I montre à Marguerite de Navarre, sa sœur, les vers qu'il vient d'écrire sur une vitre avec son diamant, (1804)

Fleury François Richard: François I montre à Marguerite de Navarre, sa sœur, les vers qu'il vient d'écrire sur une vitre avec son diamant, (1804)

- ^ Piave, Francesco Maria; Verdi, Giuseppe (c. 1930). Rigoletto. Translated by Natalia Macfarren. piano vocal score, Italian/English. New York: G. Schirmer, Inc. pp. 173ff.

- "From tomato paste to Doritos: Rigoletto aria a popular refrain" by Carrie Seidman, Sarasota Herald-Tribune, 18 October 2012

- Stan Hey (21 April 2006). "Tales from the terraces: The chants of a lifetime". The Independent. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Rossella Conte (18 April 2020). "Dal balcone di Gavinana al mondo: così il tenore conquista la città". La Nazione (in Italian). Retrieved 19 April 2022.

External links

- "La donna è mobile" on YouTube; Luciano Pavarotti in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's 1982 film Rigoletto

- Combined performance on YouTube, Pavarotti, Sting, Whitney Houston, Elton John, Carnegie Hall, 9 April 1994 Rainforest Foundation Fund benefit concert

- "La donna è mobile", translated by Randy Garrou, Aria Database

- Piano-vocal score, IMSLP

- "La donna è mobile" – Explained (7 mins) on YouTube

| Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto | |

|---|---|

| Source | |

| Films |

|

| Music | |

| Related | |