| Revision as of 15:05, 16 February 2016 editPhil wink (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users9,223 editsm tweak pic position← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:02, 4 October 2024 edit undoGhostOfNoMan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,490 edits typo fixTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} | |||

| {{Sonnet|72| | |||

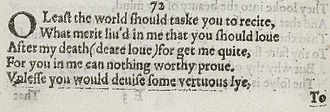

| {{Sonnet|72|Sonnet 72 1609.jpg|The first five lines of Sonnet 72 in the 1609 Quarto| | |||

| O, lest the world should task you to recite | |||

| <poem> | |||

| What merit liv’d in me, that you should love | |||

| After my death (dear love) forget me quite, | |||

| What merit lived in me, that you should love | |||

| For you in me can nothing worthy prove; | |||

| After my death,--dear love, forget me quite, | |||

| For you in me can nothing worthy prove. | |||

| Unless you would devise some virtuous lie, | Unless you would devise some virtuous lie, | ||

| To do more for me than mine own desert, | To do more for me than mine own desert, | ||

| And hang more praise upon deceased I | And hang more praise upon deceased I | ||

| Than niggard truth would willingly impart |

Than niggard truth would willingly impart; | ||

| O |

O, lest your true love may seem false in this, | ||

| That you for love speak well of me untrue, | That you for love speak well of me untrue, | ||

| My name be buried where my body is, | My name be buried where my body is, | ||

| And live no more to shame nor me nor you |

And live no more to shame nor me nor you: | ||

| :For I am shamed by that which I bring forth, | :For I am shamed by that which I bring forth, | ||

| :And so should you, to love things nothing worth. | :And so should you, to love things nothing worth. | ||

| |source=<ref>Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. ''Shakespeare’s Sonnets''. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 255 {{ISBN|9781408017975}}.</ref> | |||

| </poem>}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Sonnet 72''' is one of ] |

'''Sonnet 72''' is one of ] published by the English playwright and poet ] in 1609. It is one of the ] Sequence, which includes ] through ]. | ||

| ==Synopsis== | ==Synopsis== | ||

| Sonnet 72 continues after ], with a plea by the poet to be forgotten. The poem avoids drowning in self-pity and exaggerated modesty by mixing in touches of irony. The first quatrain presents an image of the poet as dead and not worth remembering, and suggests an ironic reversal of roles with the idea of the young man reciting words to express his love for the poet. Line five imagines that the young man, in this role, would have to lie. And line seven suggests that the young man as poet would have to “hang more praise” on the poet than the truth would allow. The couplet ends with shame and worthlessness, and the ironic suggestion of contempt for the process of writing fawning poetry to an unworthy subject.<ref>Hammond. ''The Reader and the Young Man Sonnets''. Barnes & Noble. 1981. p. 80. {{ISBN|978-1-349-05443-5}}</ref> | |||

| Sonnet 72 is an extension of ]. In it The Poet wrestles with feelings of inadequacy and mortality, specifically how his works will live on after his own death. The Poet addresses a young male lover. Throughout, The Poet urges him to forget their love and his works upon The Poet's death. | |||

| ==Structure== | |||

| ] at 21. Shakespeare's patron, and one candidate for the Fair Youth of the sonnets.]] | |||

| Sonnet 72 is an English or Shakespearean ]. The English sonnet has three ]s, followed by a final rhyming ]. It follows the typical ] of the form, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in ], a type of poetic ] based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The fifth line (accepting a 2-syllable pronunciation of "virtuous"<ref>Booth 2000, p. 258.</ref>) exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter: | |||

| <pre style="border:none;background-color:transparent;margin-left:1em"> | |||

| ==Context== | |||

| × / × / × / × / × / | |||

| ] through ] are often grouped together as a linear sequence due to their dark, brooding tone, and The Poet's obsession with his own mortality and legacy.<ref name=vendler>Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997. Print. pg. 327</ref> The sequence begins in Sonnet 71 with "No longer mourn for me when I am dead" and ends with "And that is this, and this with thee remains" in Sonnet 74.<ref name=duncan72>Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. 1997. London, New York. (2013) Print. 255-257, 52</ref> Sonnet 72 is one of 126 Sonnets coined "The Fair Youth Sequence". The identity of said "Fair Youth" remains a mystery. Several scholars point, in particular to ] and ].<ref name=duncan72/> | |||

| Unless you would devise some virtuous lie, (72.5) | |||

| </pre> | |||

| :/ = ''ictus'', a metrically strong syllabic position. × = ''nonictus''. | |||

| In line nine, the lexical stress of "true" would normally be subordinated to that of "love", fitting most naturally into <code>× /</code> which would create a variation in the meter of the line. Placing contrastive accent upon "true" preserves the regular iambic meter... | |||

| ==Poetic Structure== | |||

| <pre style="border:none;background-color:transparent;margin-left:1em"> | |||

| Sonnet 72 follows the typical ] rhyme scheme of ''abab cdcd efef gg''. There are 14 lines in the poem, 12 stanzas, or 3 quatrains, followed by 2 rhyming lines in the couplet. Unlike the common ] structure, Line 7 contains nine syllables compared to the standard ten syllables. | |||

| × / × / × / × / × / | |||

| O! lest your true love may seem false in this (72.9) | |||

| </pre> | |||

| ... which, as it is revealed later in the line, is appropriate to the sense, as "''true'' love" is contrasted with seeming "''false''" — an example of Shakespeare using metrical expectations to highlight shades of meaning. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |+Iambic Pentameter of a line of Sonnet 72<ref>Simpson, Paul. Stylistics. New York: Routledge, 2004. pg. 27. ISBN 0-415-28105-9</ref> | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| ! Stress | |||

| | x | |||

| | / | |||

| | x | |||

| | / | |||

| | x | |||

| | / | |||

| | x | |||

| | / | |||

| | x | |||

| | / | |||

| |- | |||

| !Syllable | |||

| | O | |||

| | lest | |||

| | the | |||

| | world | |||

| | should | |||

| | task | |||

| | you | |||

| | to | |||

| | re- | |||

| | -cite | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Context== | |||

| Sonnet 72 is not without its opponents debating the inconsistencies of textual layout and problematic structure. There are many inconsistencies; grammar, capitalization, and punctuation that could easily change the tone and structure of the sonnet. In the 1640 text of Sonnet 72, the L is capitalized in the first line of the Quarto, to read O Least the world. The second letter of each first line is subsequently capitalized, casting doubt on the Sonnet’s tone. It’s possible this may be due to an error of the printer, but nonetheless it slightly changes the original intent of the Sonnet.<ref name=alden>Alden, Raymond MacDonald. Modern Philology: Critical and Historical Studies in Literature, Medieval through Contemporary. University of Chicago Press Vol 14, Num 1 (1916) 17-21</ref> | |||

| ] at 21. Shakespeare's patron, and one candidate for the Fair Youth of the sonnets.]] | |||

| ] through ] group together as a sequence due to their dark, brooding tone, and the poet's obsession with his own mortality and legacy.<ref name=vendler>Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997. Print. pg. 327</ref> The sequence begins in Sonnet 71 with "No longer mourn for me when I am dead" and ends with "And that is this, and this with thee remains" in Sonnet 74.<ref name=duncan72>Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets. 1997. London, New York. (2013) Print. 255-257, 52</ref> Sonnet 72 is one of 126 Sonnets coined "The Fair Youth Sequence". The identity of said "Fair Youth" remains a mystery. Several scholars point, in particular to ] and ].<ref name=duncan72/> | |||

| ==Analysis== | ==Analysis== | ||

| Sonnet 72 is a continuation from Sonnet 71. Both sonnets are an anticipatory plea regarding death and the afterlife from the writer to the reader.<ref name=duncan72/> |

Sonnet 72 is a continuation from Sonnet 71. Both sonnets are an anticipatory plea regarding death and the afterlife from the writer to the reader.<ref name=duncan72/> The overarching subject of Sonnet 72 is The Poet's fixation with how he will be remembered after death. Subsequently the tone remains bleak and self-deprecating.<ref name=duncan72/> | ||

| John Cumming Walters states: "In the sonnets we may read the poet's intents, hopes, and fears regarding his fate, and we learn of his all consuming desire for immortality...Bodily death he does not fear: oblivion he dreads."<ref>Walters, John Cuming. The Mystery of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Attempted Elucidation. New York: Haskell House, 1972. Print.</ref> | |||

| {{cquote| | |||

| <center><small> | |||

| O! lest the world should task you to recite <br /> | |||

| What merit lived in me, that you should love <br /> | |||

| After my death,--dear love, forget me quite, <br /> | |||

| For you in me can nothing worthy prove. | |||

| In Line 2, "What merit lived in me that you should love", the poet considers his own mortality and worth. Line 7, "And hang more praise upon deceased I", derives from the practice of hanging epitaphs and trophies on the gravestone or marker of the deceased.<ref name=duncan72/> | |||

| O! lest your true love may seem false in this<br /> | |||

| That you for love speak well of me untrue,<br /> | |||

| My name be buried where my body is,<br /> | |||

| And live no more to shame nor me nor you.<br /> | |||

| </small></center>|}} | |||

| Line 13 of the couplet,"For I am shamed by that which I bring forth," may refer to, or resonate with the ] verses in ]: 7.20-23: | |||

| A modern translation reads: | |||

| :"That which cometh out of the man, that defileth the man. For from within, out of the heart of men, proceed evil thoughts, adulteries, fornications, murders, thefts, covetousness, wickedness, deceit, lasciviousness, an evil eye, blasphemy, foolishness: all these evil things come from within and defile the man."<ref name=duncan72/> | |||

| {{cquote| | |||

| <center><small> | |||

| O, in case they demand to know why you loved me, just forget me <br /> | |||

| when I die. You can’t find virtue in me unless you overpraise. | |||

| O, in case your love should lead you into untruth, forget me rather than <br /> | |||

| live on to shame us, me for what I produce, you for loving rubbish.<ref>Shakespeare, William, and David West. Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: Duckworth Overlook, 2007. Print</ref><br /> | |||

| </small></center>|}} | |||

| The overarching subject of Sonnet 72 is The Poet's fixation with how he will be remembered after death. Subsequently the tone remains bleak and self-depreciating.<ref name=duncan72/> | |||

| ===Theme=== | |||

| {{cquote| | |||

| <center><small>In the sonnets we may read the poet's intents, hopes, and fears regarding his fate, and we learn of his all consuming desire for immortality...Bodily death he does not fear: oblivion he dreads.”- John Cumming Walters, ''Mystery of Shakespeare's Sonnets''<ref>Walters, John Cuming. The Mystery of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Attempted Elucidation. New York: Haskell House, 1972. Print.</ref> | |||

| </small></center>|}} | |||

| In Line 2 The Poet discusses his own mortality and worth by asking, "What merit lived in me that you should love". Keeping with his theme of death, The Poet employs the use of morbid imagery in Line 7: "And hang more praise upon deceased I". A reference to the practice of the time of hanging Epitaphs/Trophies on the gravestone or marker of the deceased.<ref name=duncan72/> Line 10 states "that you for love speak well of me untrue". Here The Poet is stating if his young lover were to speak well of him after death, he would be lying. | |||

| The last couplet of the sonnet alludes that a dead poet is worthless, or has no value. "For I am shamed by that which I bring forth/And so should you, to love things nothing worth." | |||

| ==Exegesis== | |||

| The text of Shakespeare’s sonnets has been open to debate for quite some time. In 1640, a volume of poems was issued by John Benson of St. Dunstan’s Chuchyard, which contained several pieces that had been collected in 1609. The collection is often thought of as the second edition of Sonnets, and may not be the version that Shakespeare publicly acknowledged or intended for the public to see.<ref name=alden/> | |||

| Line 13 of the couplet states: "For I am shamed by that which I bring forth." This refers to the ] verses in ]: 7.20-23 “That which cometh...and defile the man.” Line 14 of the couplet states: "And so should you, to love things nothing worth." This alludes to the Biblical verse in ] 24.25 “Who will make me a liar, and make my speech nothing worth?” Here, The Poet is utilizing Biblical texts to reaffirm the baseless nature of both himself and his poetry.<ref name=duncan72/> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{Shakespeare}} | |||

| {{Shakespeare sonnets bibliography}} | |||

| {{Shakespeare}} | |||

| {{Shakespeare's sonnets}} | {{Shakespeare's sonnets}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Sonnet 072}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:02, 4 October 2024

Poem by William Shakespeare

| «» Sonnet 72 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The first five lines of Sonnet 72 in the 1609 Quarto The first five lines of Sonnet 72 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 72 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is one of the Fair Youth Sequence, which includes Sonnet 1 through Sonnet 126.

Synopsis

Sonnet 72 continues after Sonnet 71, with a plea by the poet to be forgotten. The poem avoids drowning in self-pity and exaggerated modesty by mixing in touches of irony. The first quatrain presents an image of the poet as dead and not worth remembering, and suggests an ironic reversal of roles with the idea of the young man reciting words to express his love for the poet. Line five imagines that the young man, in this role, would have to lie. And line seven suggests that the young man as poet would have to “hang more praise” on the poet than the truth would allow. The couplet ends with shame and worthlessness, and the ironic suggestion of contempt for the process of writing fawning poetry to an unworthy subject.

Structure

Sonnet 72 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The fifth line (accepting a 2-syllable pronunciation of "virtuous") exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Unless you would devise some virtuous lie, (72.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

In line nine, the lexical stress of "true" would normally be subordinated to that of "love", fitting most naturally into × / which would create a variation in the meter of the line. Placing contrastive accent upon "true" preserves the regular iambic meter...

× / × / × / × / × / O! lest your true love may seem false in this (72.9)

... which, as it is revealed later in the line, is appropriate to the sense, as "true love" is contrasted with seeming "false" — an example of Shakespeare using metrical expectations to highlight shades of meaning.

Context

Sonnet 71 through Sonnet 74 group together as a sequence due to their dark, brooding tone, and the poet's obsession with his own mortality and legacy. The sequence begins in Sonnet 71 with "No longer mourn for me when I am dead" and ends with "And that is this, and this with thee remains" in Sonnet 74. Sonnet 72 is one of 126 Sonnets coined "The Fair Youth Sequence". The identity of said "Fair Youth" remains a mystery. Several scholars point, in particular to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton and William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke.

Analysis

Sonnet 72 is a continuation from Sonnet 71. Both sonnets are an anticipatory plea regarding death and the afterlife from the writer to the reader. The overarching subject of Sonnet 72 is The Poet's fixation with how he will be remembered after death. Subsequently the tone remains bleak and self-deprecating.

John Cumming Walters states: "In the sonnets we may read the poet's intents, hopes, and fears regarding his fate, and we learn of his all consuming desire for immortality...Bodily death he does not fear: oblivion he dreads."

In Line 2, "What merit lived in me that you should love", the poet considers his own mortality and worth. Line 7, "And hang more praise upon deceased I", derives from the practice of hanging epitaphs and trophies on the gravestone or marker of the deceased.

Line 13 of the couplet,"For I am shamed by that which I bring forth," may refer to, or resonate with the Biblical verses in Mark: 7.20-23:

- "That which cometh out of the man, that defileth the man. For from within, out of the heart of men, proceed evil thoughts, adulteries, fornications, murders, thefts, covetousness, wickedness, deceit, lasciviousness, an evil eye, blasphemy, foolishness: all these evil things come from within and defile the man."

References

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 255 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Hammond. The Reader and the Young Man Sonnets. Barnes & Noble. 1981. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-349-05443-5

- Booth 2000, p. 258.

- Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997. Print. pg. 327

- ^ Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets. 1997. London, New York. (2013) Print. 255-257, 52

- Walters, John Cuming. The Mystery of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Attempted Elucidation. New York: Haskell House, 1972. Print.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets . Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) . Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) . Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) . The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

| Shakespeare's sonnets | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Fair Youth" sonnets |

|  | ||||||

| "Dark Lady" sonnets |

| |||||||