| Revision as of 09:27, 29 October 2017 editEtrifax (talk | contribs)382 edits →Amesbury Priory: reduced size of image of Henry II← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:29, 27 October 2024 edit undoA bit iffy (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers48,526 edits + short description | ||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 18 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Benedictine abbey in Wiltshire, England}} | |||

| ⚫ | '''Amesbury Abbey''' was a ] ] of women at ] in ], England, founded by ] in about the year 979 on what may have been the site of an earlier ]. |

||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| ⚫ | '''Amesbury Abbey''' was a ] ] of women at ] in ], England, founded by ] in about the year 979 on what may have been the site of an earlier ]. The abbey was dissolved in 1177 by ], who founded in its place a house of the Order of ], known as ]. | ||

| The name Amesbury Abbey is now used by a nearby |

The name Amesbury Abbey is now used by a nearby ] ] built in the 1830s, currently a nursing home. | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| <div style="float:right;clear:right"> | |||

| ] | ]</div> | ||

| Amesbury was already a sacred place in ] times, and there are legends that a ] existed there before the Danish invasions. There may have been an existing cult of ] which led Ælfthryth to choose Amesbury. Melor,<ref> |

Amesbury was already a sacred place in ] times, and there are legends that a ] existed there before the Danish invasions. There may have been an existing cult of ] which led Ælfthryth to choose Amesbury. Melor,<ref>Cf. François Plaine, ''Vita inedita sancti Melori martyris'', in ''Analecta Bollandiana'' 5 (1886) 166-176; ''Acta Sanctorum, Octobris XI'', p. 943; ''Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina antiquae et mediae aetatis'', Brussels, 1901, vol. 2, p. 862</ref> the son of a leader of ] and a boy-martyr, was buried at ] and venerated in ], but a later tradition claims that some of his relics were brought to Amesbury and sold to the abbess. However, the 12th-century life of St Melor says the nunnery at Amesbury was founded before Melor's relics arrived.<ref name=wvch>, in ], Elizabeth Crittall, eds., ], Vol. 3 (University of London, 1956) pp.242–259</ref> The cult of St Melor is commemorated in the dedication of the ]. | ||

| ===Saxon |

===Saxon abbey=== | ||

| ⚫ | The monastery was founded by ] in about the year 979 on what may have been the site of an earlier ]. She founded two religious houses at about the same time, the other being at ] in Hampshire. Ælfthryth's motive was long believed to be contrition for the murder of ], another boy-martyr, making the date of 979 given by the ] appropriate. However, she is now considered not to have been personally responsible for the murder.<ref name="wvch" /> | ||

| ⚫ | At the time of the ] (1086), the abbey held, as it had had in ]'s time, the Wiltshire ] of ], ], ], ], and ], totalling twenty-seven ], together with the manor of Rabson in ]. In ] it held Ceveslane in ], ], and ] and the church at ].<ref name="wvch" /> | ||

| ⚫ | The monastery was founded by ] in about the year 979 on what may have been the site of an earlier ]. She founded two religious houses at about the same time, the other being at ] in ]. | ||

| ⚫ | It seems that for most of its existence Amesbury Abbey was probably not of particular importance and its overall income was not especially high. It was, like all women's houses in particular, liable to harassment, rustling and other incursions by powerful neighbours, as well as abusive tax exactions. At the £54 and 15 shillings that its income reached, it was admittedly just above ] (]) and ] (]), but it was less than other nunneries in its region, such as ] (]), ] (]) or ] (]).<ref>David Knowles, ''The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St. Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council, 940-1216'', Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1963. pp. 702-703.</ref> | ||

| Ælfthryth's motive was long believed to be contrition for the murder of ], making the date of 979 given by the ] appropriate. However, she is now considered not to have been personally responsible for the murder.<ref name=wvch>{{cite web|website=British History Online|title=Victoria County History: Wiltshire: Vol 3 pp242–259 – Houses of Benedictine nuns: Abbey, later priory, of Amesbury|editor-first1=R.B.|editor-last1=Pugh|editor-first2=Elizabeth|editor-last2=Crittall|url=|publisher=University of London|date=1956|accessdate=30 September 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | As to the Abbesses of Amesbury, the references are sparse. For the period before the Conquest there is only a retrospective mention much later of Heahpled (?), in the years 979 and 1013, and at the time of the house's re-foundation, of the then incumbent Abbess, Beatrice (1177).<ref name="wvch" /> | ||

| ⚫ | At the time of the ] (1086), the abbey held, as it had had in ]'s time, the Wiltshire ] of ], ], |

||

| ⚫ | It seems that for most of its existence Amesbury Abbey was probably not of particular importance and its |

||

| ⚫ | As to the Abbesses of Amesbury, the references are |

||

| ===New foundation=== | ===New foundation=== | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main| Amesbury Priory}} | ||

| In 1177 Ælfthryth's foundation was dissolved by ] and reconstituted as a house of the Order of ],<ref name=wvch /> a Benedictine reform. | In 1177 Ælfthryth's foundation was dissolved by ] and reconstituted as a house of the Order of ],<ref name=wvch /> a Benedictine reform. | ||

| ] issued a bull on 15 September 1176 approving the plan but specifying that the ] and the bishops of ], ] and ] were to visit the convent and notify the nuns of the need to cooperate. Any nun who declined to join the new Order was to be transferred to another monastery and treated well. The new regime was then to be introduced and when the commission of bishops decided the moment had come, the abbess and a party of nuns from ] were to come to complete the handover.<ref name=wvch /> | ] issued a bull on 15 September 1176 approving the plan but specifying that the ] and the bishops of ], ] and ] were to visit the convent and notify the nuns of the need to cooperate. Any nun who declined to join the new Order was to be transferred to another monastery and treated well. The new regime was then to be introduced, and when the commission of bishops decided the moment had come, the abbess and a party of nuns from ] were to come to complete the handover.<ref name=wvch /> | ||

| Things did not go quite as smoothly as this formula suggested, though the accounts may display a natural bias against the existing community. In the event, it was said that scandal was discovered when the bishops of Exeter and Worcester made their inspection in the octave of the feast of St Hilary, 1177. The abbess was deposed and dismissed with a pension.<ref> |

Things did not go quite as smoothly as this formula suggested, though the accounts may display a natural bias against the existing community. In the event, it was said that scandal was discovered when the bishops of Exeter and Worcester made their inspection in the octave of the feast of St Hilary, 1177. The abbess was deposed and dismissed with a pension.<ref>Eileen E. Power, ''Medieval English Nunneries c 1275 to 1535'', Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1922, p. 455.</ref> Some of the other nuns were compromised and unrepentant and these were also expelled. Those willing to make amends received the offer to stay on; it seems that there were some 30 nuns and they were all expelled.<ref name=wvch /> | ||

| The party that |

The party that Henry II then summoned from Fontevraud were in the end some 21 or 24 nuns, led not by the Abbess of Fontevraud but by a former subprioress. Some nuns were also brought from ] in Worcestershire, also a Fontevraud house. The new community was solemnly installed on 22 May in the King's presence by the Archbishop of Canterbury, accompanied by several other bishops.<ref name=wvch /> | ||

| ===Order of |

===Order of Fontevraud=== | ||

| ] | <div style="float:right;clear:right">]]]</div> | ||

| The ]s were great benefactors of the mother abbey at ] in its early years, and ]'s widow, ], went to live there. That monastery, founded in 1101,<ref>Jean Dalarun, ''Robert d Arbrissel, fondateur de Fontevraud'' (Paris: Albin Michel, 1986); Gabrielle Esperdy, ''The Royal Abbey of Fontevrault: Religious Women and the Shaping of Gendered Space'', in ''Journal of International Women's Studies'' 6: 2 (2006) 59–80. http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol6/iss2/5 ; Fiona J. Griffiths, ''The Cross and the Cura monialium: Robert of Arbrissel, John the Evangelist, and the Pastoral Care of Women in the Age of Reform'', in ''Speculum'' 83 (2008) 303–330.</ref> became the chosen mausoleum of the Angevin dynasty and the centre of a new monastic order, the Order of Fontevraud. | |||

| The Fontevraud monastic reform |

The Fontevraud monastic reform followed in part the lead of the highly influential and prestigious ] in adopting a ], whereby in a federated structure the superiors of subsidiary houses were in effect deputies of the Abbot of Cluny, the head of the Order, and their houses were hence usually styled ], not ]s, governed therefore not by ]s but by ]s.<ref>Michael Ott, ''Priory'', in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 12'', New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911; George Cyprian Alston, ''Congregation of Cluny'', in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia. vol. 4'', New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. </ref> In the analogous case of the Order of Fontevraud, its head was the Abbess of Fontevraud, who at the death of the Order's founder, ], in about 1117, already had under her rule 35 priories, and by the end of that century about 100, in France, Spain and England.<ref>Jean Favier, ''Les Plantagenêts: Origine et destin d'un empire,'' (Poitiers: Fayard, 2004), p. 152</ref> | ||

| Fontevraud also took up a feature that had appeared sporadically in early centuries, whereby its houses were ], with separately housed convents of both men and women, under a common superior, which in the case of the Order of Fontevraud was a prioress. The men had their own male superior, but he was subject to the prioress. At Amesbury and in some other places this model seems to have broken down, and by the beginning of the 15th century Amesbury seems to have become an exclusively women's house, with a small group of priest-chaplains external to the Order. | |||

| ⚫ | ===Amesbury Priory=== | ||

| With the passing of the Plantagenet dynasty, Fontevrault and her dependencies began to fall upon hard times, and the decline was worsened by the devastation of the 14th century ]. In 1460 a ] of fifty of the priories of the Order revealed most of them to be barely occupied, if not abandoned.<ref> Carlos M. N. Eire, ''Reformations: The Early Modern World, 1450–1650'', Yale University Press, New Haven, 2016, p. 127.</ref> | |||

| <div style="float:right;clear:right"> | |||

| ⚫ | ]</div> | ||

| ⚫ | Though it was above all Henry II who over his long reign (1154–1189) introduced the Order of Fontevraud into England, there seem only ever to have been in the country four houses in all. Apart from Amesbury, these were ] (Worcestershire),<ref>''Houses of Benedictine nuns: Priory of Westwood'', in J.W. Willis-Bund & William Page (eds.), ''A History of the County of Worcester, vol. 2'', London, 1971, pp. 148–151. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/worcs/vol2/pp148-151 .</ref> Eaton or ] (Warwickshire)<ref>''Houses of Benedictine nuns: Priory of Nuneaton'', in William Page (ed.), ''A History of the County of Warwick. vol. 2'', London, 1908, pp. 66–70. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/warks/vol2/pp66-70 .</ref> and ] (Bedfordshire),<ref>''Alien house: Priory of La Grave or Grovebury'', in ''A History of the County of Bedford, vol. 1'', London, 1904, pp. 403–404. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/beds/vol1/pp403-404 .</ref> the latter three founded roughly between 1133 and 1164, so before Henry revamped the foundation at Amesbury about 1177. | ||

| Although the later Amesbury monastery is popularly referred to as an "abbey", it was not one. The first monastery appears to have been truly an abbey, but the Fontevraud daughter house was always a priory. Perhaps the fading memory of historical fact after the ], the end of links with Rome, and later the inroads of ], explain the use of the word. The choice of the name for the later country house may also have been a factor. | |||

| ⚫ | ===Amesbury Priory=== | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | Though it was above all Henry II who over his long reign ( |

||

| ⚫ | ====Some women of Amesbury Priory==== | ||

| Although the later Amesbury monastery is popularly referred to as an "Abbey", this is not strictly exact. Presumably the fading memory of historical fact after the Reformation, aided by the elimination of Catholicism, and later the inroads of Romanticism accounts for the usage. Doubtless also the search for a elegant name for the later nearby mansion counted for something. The first monastery appears to have truly been an abbey, but the Fontevraud daughter house was always technically a priory. | |||

| ⚫ | ] (died 1241), a princess held captive for most of her life for her presumable claim to the English throne, donated her body and was buried here, and in 1268 ] would grant to the abbey a manor of ] in suffrage for her soul and that of her brother ], who was widely believed to have been murdered by Henry III's father ]; Henry III would also order the abbey to have Eleanor and Arthur commemorated as well as the late English kings and queens. | ||

| ⚫ | ], ] of ], died in ] on 24 or 25 June 1291, and was buried in the abbey on 11 September 1291. | ||

| ===Prioresses of Amesbury=== | |||

| The list that follows is incomplete.<ref name=wvch /> | |||

| ⚫ | From about at least 1343 to her death some time before February 1349, ] was Prioress of Amesbury. She was the sister of ], a great-grandson of ]. She was also younger sister of the formidable ]. In 1347, the twice-widowed Maud also entered a nunnery, in her case ], a house of Augustinian canonesses near ] in Suffolk, but in 1364 she transferred to the ] community at ], also in Suffolk, where she died and was buried in 1377. | ||

| *Joan d'Osmont (late Henry II, who died 1189) | |||

| *Emeline (1208, 1221) | |||

| *Felise (1227, 1237) | |||

| *Ida (1256, 1273) | |||

| *Alice (1290) | |||

| *Margaret (1293) | |||

| *Joan de Gennes (1294, mentioned 1309) | |||

| *Isabel de Geinville, Geyville, or Geneville (1309,<ref> Request for royal confirmation of election.</ref> 1337) | |||

| *] (1343, 1347; died before 4 February 1349) | |||

| *Margery of Purbrook (1349; died before 28 October 1379) | |||

| *Eleanor St. Manifee (1379;<ref> Royal assent to election.</ref> died before 20 November 1391) | |||

| *Sibyl Montague (1391;<ref> Royal assent to election.</ref> died 1420) | |||

| *Mary Gore (1420;<ref> Royal assent to election.</ref> 1437) | |||

| *Joan Benfeld (1437, 1466; died before 6 March 1469) | |||

| *Joan Arnold (1469, 1474; died before December 1480) | |||

| *Alice Fisher (1480, 1491; 1486)<ref> Confirmation by the Abbess of Fontevrault.</ref> | |||

| *Katherine Dicker (1502, 1507) | |||

| *Christine Fountleroy (1510, 1519) | |||

| *Florence Bonnewe (1530, 1539) | |||

| *Joan Darrell (1533, 1539) | |||

| Not half a century later, the prioress was Sybil Montague, a woman well-placed as a niece of ] (d.1389) and sister of ].<ref>Douglas Richardson, ''Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, vol. 1'', Everington, Salt Lake City, 2nd edition 2001, p. 157.</ref> Her election as prioress in 1391 was confirmed by the King, ].<ref name="wvch"/> Dame Sybil seems in effect to have abolished the system of male priors, though this caused a great upheaval and involved the intervention of the new King, ], against the background of his seizure of power from Richard II. Dame Sybil seems to have navigated the rapids and remained prioress, dying in 1420.<ref name="wvch"/> | |||

| ===Priors of Amesbury=== | |||

| The list that follows is incomplete.<ref name=wvch /> | |||

| *John (1194) | |||

| *Robert (1198) | |||

| *John (about 1215–1221) | |||

| *John de Vinci (1227) | |||

| *Peter (1293) | |||

| *John of Figheldean (before 1316) | |||

| *Richard of Greenborough (1316, 1318) | |||

| *John of Holt (1356, 1357) | |||

| *William of Amesbury (1361) | |||

| *John Winterbourne (about 1379) | |||

| *Robert Dawbeney (before 1399) | |||

| It is possible that the original system of a parallel community of monks broke down at some point and that secular priests were then appointed as chaplains. | |||

| ⚫ | ===Some women of Amesbury=== | ||

| ⚫ | ] (died 1241), a princess held captive for most of her life, donated her body and was buried here, and |

||

| ⚫ | ], ] of ], died in ] on 24 or 25 June 1291, and was buried in the abbey on 11 September 1291. | ||

| ⚫ | From about at least 1343 to her death some time before February 1349, ] |

||

| Not half a century later, the prioress was Sybil Montague, a woman well-placed as a niece of ], who died in 1389 and sister of ], and of ], who was ] from 1382.<ref> Douglas Richardson, ''Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, vol. 1'', Everington, Salt Lake City, 2nd edition 2001, p. 157. </ref> Sybil’s election as prioress in 1391 was confirmed by the King, ].<ref> ''Houses of Benedictine nuns: Abbey, later priory, of Amesbury'', in R.B. Pugh & Elizabeth Crittall (edd.), ''A History of the County of Wiltshire, vol. 3'', London, 1956, pp. 242-259. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol3/pp242-259 .</ref> In 1398 Dame Sybil had the elderly Prior Robert Daubeneye thrown out of the monastery. The mixed royal and ecclesiastical enquiries into the resulting uproar compromised by saving the reputation of the Prior and ordering the granting of a pension, but not reinstating him in the house. Sybil had sown the seeds of a storm and on 14 March 1400 the monastery was invaded after nightfall by ruffians who imprisoned Sybil and some of the nuns for at least two days. It took the involvement of ] and his orders to officers of the crown to free them and restore order. They were troubled times, but Dame Sybil seems to have navigated the rapids and was to die only in 1420.<ref> ''Houses of Benedictine nuns: Abbey, later priory, of Amesbury'', in R.B. Pugh & Elizabeth Crittall (edd.), ''A History of the County of Wiltshire, vol. 3'', London, 1956, pp. 242-259. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol3/pp242-259 . For some of the broader social background to the incident, cf. Caroline Dunn, ''Stolen Women in Medieval England: Rape, Abduction, and Adultery, 1100–1500'', Cambridge University Press, 2015 (= ''Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought, Fourth Series'' 87).</ref> | |||

| ===Dissolution=== | ===Dissolution=== | ||

| ⚫ | It is possible that Amesbury ], the ], is the former priory church, and this may explain why it was spared at the time of the ], though the priory and its other buildings were destroyed. The church is a ] building.<ref>{{NHLE|num=1182066|desc=Church of St Mary and St Melor|accessdate=27 October 2014|fewer-links=yes}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | The Amesbury estate was subsequently obtained from ] by ],<ref>John Chandler & Peter Goodhugh, ''Amesbury: history and description of a south Wiltshire town'' (1989), p. 24</ref> a nephew to ], ] of ], and the eldest son of her brother, ], ] during the minority of King ], the Earl's cousin, with whom he had been educated in infancy.<ref name = "alb">Albert Frederick Pollard, "Seymour, Edward (1539?–1621)", ''Dictionary of National Biography'', 1885–1900, Volume 51(1897).</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | It |

||

| ==19th-century house== | |||

| ⚫ | The Amesbury estate was subsequently obtained from ] by ],<ref>John Chandler & Peter Goodhugh, ''Amesbury: history and description of a south Wiltshire town'' (1989), p. 24</ref> a nephew to ], ] of ], and the eldest son of her brother, ], ] during the minority of King ], the Earl's cousin, with whom he had been educated in infancy.<ref name = "alb">Albert Frederick Pollard, "Seymour, Edward (1539?–1621)", ''Dictionary of National Biography'', 1885–1900, Volume 51(1897).</ref> | ||

| <div style="float:right;clear:right">]</div> | |||

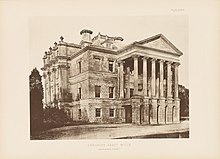

| The nearby ], also called ], was not part of the nunnery: it was built in 1834–1840 by architect ] for ]. It has three storeys and attics, and replaced a previous house built in 1660–1661 by John Webb for ]. The main south front has nine bays, of which five sit behind a portico of six composite columns.<ref name="listing">{{National Heritage List for England|num=1131079|desc=Amesbury Abbey|access-date=16 May 2021}}</ref> | |||

| The house was designated as Grade I listed in 1953,<ref name="listing" /> and is now used as a care home. It stands in pleasure grounds and parkland, in all about {{Convert|56|ha|acre|abbr=|order=flip}}, which are listed Grade II* on the ].<ref>{{National Heritage List for England |num=1000469 |desc=Amesbury Abbey (park and garden) |access-date=7 March 2023 |fewer-links=yes}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| The nearby ], also called Amesbury Abbey, stands in 35 acres of parkland<ref>{{coord|51.1745|-1.7854|format=dms|type:landmark_region:GB|display=inline}}</ref> and was not part of the nunnery. It was built in 1834–1840 by architect ] for ]. | |||

| It was constructed in a cubic form of Chilmark limestone ashlar with slate roofs with three storeys and attics, and replaced a previous house built in 1660–1661 by John Webb for the second Duke of Somerset. The main south front has nine bays, of which five sit behind a portico of six composite columns. The main entrance was originally on a ] behind the colonnade.<ref name= EH/> The house is now used as a nursing home. The name Amesbury Abbey is also used by the company which runs it and several other similar facilities. | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| {{coord|51.1719|-1.7843|type:landmark_region:GB|display=title}} | {{coord|51.1719|-1.7843|type:landmark_region:GB|display=title}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:29, 27 October 2024

Benedictine abbey in Wiltshire, EnglandAmesbury Abbey was a Benedictine abbey of women at Amesbury in Wiltshire, England, founded by Queen Ælfthryth in about the year 979 on what may have been the site of an earlier monastery. The abbey was dissolved in 1177 by Henry II, who founded in its place a house of the Order of Fontevraud, known as Amesbury Priory.

The name Amesbury Abbey is now used by a nearby Grade I listed country house built in the 1830s, currently a nursing home.

History

Amesbury was already a sacred place in pagan times, and there are legends that a monastery existed there before the Danish invasions. There may have been an existing cult of St Melor which led Ælfthryth to choose Amesbury. Melor, the son of a leader of Cornouaille and a boy-martyr, was buried at Lanmeur and venerated in Brittany, but a later tradition claims that some of his relics were brought to Amesbury and sold to the abbess. However, the 12th-century life of St Melor says the nunnery at Amesbury was founded before Melor's relics arrived. The cult of St Melor is commemorated in the dedication of the current Amesbury parish church.

Saxon abbey

The monastery was founded by Queen Ælfthryth in about the year 979 on what may have been the site of an earlier monastery. She founded two religious houses at about the same time, the other being at Wherwell in Hampshire. Ælfthryth's motive was long believed to be contrition for the murder of Edward, another boy-martyr, making the date of 979 given by the Melrose chronicle appropriate. However, she is now considered not to have been personally responsible for the murder.

At the time of the Domesday Book (1086), the abbey held, as it had had in King Edward's time, the Wiltshire manors of Bulford, Boscombe, Allington, Coulston, and Maddington, totalling twenty-seven hides, together with the manor of Rabson in Winterbourne Bassett. In Berkshire it held Ceveslane in Challow, Fawley, and Kintbury and the church at Letcombe Regis.

It seems that for most of its existence Amesbury Abbey was probably not of particular importance and its overall income was not especially high. It was, like all women's houses in particular, liable to harassment, rustling and other incursions by powerful neighbours, as well as abusive tax exactions. At the £54 and 15 shillings that its income reached, it was admittedly just above Wherwell Abbey (Hampshire) and Chatteris Abbey (Cambridgeshire), but it was less than other nunneries in its region, such as Wilton Abbey (Wiltshire), Shaftesbury Abbey (Dorset) or Romsey Abbey (Hampshire).

As to the Abbesses of Amesbury, the references are sparse. For the period before the Conquest there is only a retrospective mention much later of Heahpled (?), in the years 979 and 1013, and at the time of the house's re-foundation, of the then incumbent Abbess, Beatrice (1177).

New foundation

Main article: Amesbury PrioryIn 1177 Ælfthryth's foundation was dissolved by Henry II and reconstituted as a house of the Order of Fontevraud, a Benedictine reform.

Pope Alexander III issued a bull on 15 September 1176 approving the plan but specifying that the Archbishop of Canterbury and the bishops of London, Exeter and Worcester were to visit the convent and notify the nuns of the need to cooperate. Any nun who declined to join the new Order was to be transferred to another monastery and treated well. The new regime was then to be introduced, and when the commission of bishops decided the moment had come, the abbess and a party of nuns from Fontevraud Abbey were to come to complete the handover.

Things did not go quite as smoothly as this formula suggested, though the accounts may display a natural bias against the existing community. In the event, it was said that scandal was discovered when the bishops of Exeter and Worcester made their inspection in the octave of the feast of St Hilary, 1177. The abbess was deposed and dismissed with a pension. Some of the other nuns were compromised and unrepentant and these were also expelled. Those willing to make amends received the offer to stay on; it seems that there were some 30 nuns and they were all expelled.

The party that Henry II then summoned from Fontevraud were in the end some 21 or 24 nuns, led not by the Abbess of Fontevraud but by a former subprioress. Some nuns were also brought from Westwood Priory in Worcestershire, also a Fontevraud house. The new community was solemnly installed on 22 May in the King's presence by the Archbishop of Canterbury, accompanied by several other bishops.

Order of Fontevraud

effigy (now lost) at Fontevraud

The Plantagenets were great benefactors of the mother abbey at Fontevraud in its early years, and Henry II's widow, Eleanor of Aquitaine, went to live there. That monastery, founded in 1101, became the chosen mausoleum of the Angevin dynasty and the centre of a new monastic order, the Order of Fontevraud.

The Fontevraud monastic reform followed in part the lead of the highly influential and prestigious Cluny Abbey in adopting a centralized form of government, whereby in a federated structure the superiors of subsidiary houses were in effect deputies of the Abbot of Cluny, the head of the Order, and their houses were hence usually styled priories, not abbeys, governed therefore not by abbots but by priors. In the analogous case of the Order of Fontevraud, its head was the Abbess of Fontevraud, who at the death of the Order's founder, Robert of Arbrissel, in about 1117, already had under her rule 35 priories, and by the end of that century about 100, in France, Spain and England.

Fontevraud also took up a feature that had appeared sporadically in early centuries, whereby its houses were double monasteries, with separately housed convents of both men and women, under a common superior, which in the case of the Order of Fontevraud was a prioress. The men had their own male superior, but he was subject to the prioress. At Amesbury and in some other places this model seems to have broken down, and by the beginning of the 15th century Amesbury seems to have become an exclusively women's house, with a small group of priest-chaplains external to the Order.

Amesbury Priory

Though it was above all Henry II who over his long reign (1154–1189) introduced the Order of Fontevraud into England, there seem only ever to have been in the country four houses in all. Apart from Amesbury, these were Westwood Priory (Worcestershire), Eaton or Nuneaton Priory (Warwickshire) and Grovebury Priory (Bedfordshire), the latter three founded roughly between 1133 and 1164, so before Henry revamped the foundation at Amesbury about 1177.

Although the later Amesbury monastery is popularly referred to as an "abbey", it was not one. The first monastery appears to have been truly an abbey, but the Fontevraud daughter house was always a priory. Perhaps the fading memory of historical fact after the English Reformation, the end of links with Rome, and later the inroads of Romanticism, explain the use of the word. The choice of the name for the later country house may also have been a factor.

Some women of Amesbury Priory

Eleanor of Brittany (died 1241), a princess held captive for most of her life for her presumable claim to the English throne, donated her body and was buried here, and in 1268 King Henry III would grant to the abbey a manor of Melksham in suffrage for her soul and that of her brother Arthur, who was widely believed to have been murdered by Henry III's father King John; Henry III would also order the abbey to have Eleanor and Arthur commemorated as well as the late English kings and queens.

Eleanor of Provence, Queen consort of Henry III of England, died in Amesbury on 24 or 25 June 1291, and was buried in the abbey on 11 September 1291.

From about at least 1343 to her death some time before February 1349, Isabel of Lancaster was Prioress of Amesbury. She was the sister of Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, a great-grandson of Henry III. She was also younger sister of the formidable Maud of Lancaster, Countess of Ulster. In 1347, the twice-widowed Maud also entered a nunnery, in her case Campsey Priory, a house of Augustinian canonesses near Wickham Market in Suffolk, but in 1364 she transferred to the Poor Clares community at Bruisyard Abbey, also in Suffolk, where she died and was buried in 1377.

Not half a century later, the prioress was Sybil Montague, a woman well-placed as a niece of William Montague, 2nd Earl of Salisbury (d.1389) and sister of John Montague, 3rd Earl of Salisbury. Her election as prioress in 1391 was confirmed by the King, Richard II. Dame Sybil seems in effect to have abolished the system of male priors, though this caused a great upheaval and involved the intervention of the new King, Henry IV, against the background of his seizure of power from Richard II. Dame Sybil seems to have navigated the rapids and remained prioress, dying in 1420.

Dissolution

It is possible that Amesbury parish church, the Church of St Mary and St Melor, is the former priory church, and this may explain why it was spared at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, though the priory and its other buildings were destroyed. The church is a Grade I listed building.

The Amesbury estate was subsequently obtained from the Crown by Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, a nephew to Jane Seymour, Queen consort of Henry VIII, and the eldest son of her brother, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of England during the minority of King Edward VI, the Earl's cousin, with whom he had been educated in infancy.

19th-century house

The nearby country house, also called Amesbury Abbey, was not part of the nunnery: it was built in 1834–1840 by architect Thomas Hopper for Sir Edmund Antrobus. It has three storeys and attics, and replaced a previous house built in 1660–1661 by John Webb for William Seymour, 2nd Duke of Somerset. The main south front has nine bays, of which five sit behind a portico of six composite columns.

The house was designated as Grade I listed in 1953, and is now used as a care home. It stands in pleasure grounds and parkland, in all about 140 acres (56 ha), which are listed Grade II* on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest.

References

- Cf. François Plaine, Vita inedita sancti Melori martyris, in Analecta Bollandiana 5 (1886) 166-176; Acta Sanctorum, Octobris XI, p. 943; Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina antiquae et mediae aetatis, Brussels, 1901, vol. 2, p. 862

- ^ "Houses of Benedictine nuns: Abbey, later priory, of Amesbury", in Ralph Pugh, Elizabeth Crittall, eds., Wiltshire Victoria County History, Vol. 3 (University of London, 1956) pp.242–259

- David Knowles, The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St. Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council, 940-1216, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1963. pp. 702-703.

- Eileen E. Power, Medieval English Nunneries c 1275 to 1535, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1922, p. 455.

- Jean Dalarun, Robert d Arbrissel, fondateur de Fontevraud (Paris: Albin Michel, 1986); Gabrielle Esperdy, The Royal Abbey of Fontevrault: Religious Women and the Shaping of Gendered Space, in Journal of International Women's Studies 6: 2 (2006) 59–80. http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol6/iss2/5 ; Fiona J. Griffiths, The Cross and the Cura monialium: Robert of Arbrissel, John the Evangelist, and the Pastoral Care of Women in the Age of Reform, in Speculum 83 (2008) 303–330.

- Michael Ott, Priory, in The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 12, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911; George Cyprian Alston, Congregation of Cluny, in The Catholic Encyclopedia. vol. 4, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908.

- Jean Favier, Les Plantagenêts: Origine et destin d'un empire, (Poitiers: Fayard, 2004), p. 152

- Houses of Benedictine nuns: Priory of Westwood, in J.W. Willis-Bund & William Page (eds.), A History of the County of Worcester, vol. 2, London, 1971, pp. 148–151. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/worcs/vol2/pp148-151 .

- Houses of Benedictine nuns: Priory of Nuneaton, in William Page (ed.), A History of the County of Warwick. vol. 2, London, 1908, pp. 66–70. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/warks/vol2/pp66-70 .

- Alien house: Priory of La Grave or Grovebury, in A History of the County of Bedford, vol. 1, London, 1904, pp. 403–404. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/beds/vol1/pp403-404 .

- Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, vol. 1, Everington, Salt Lake City, 2nd edition 2001, p. 157.

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary and St Melor (1182066)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- John Chandler & Peter Goodhugh, Amesbury: history and description of a south Wiltshire town (1989), p. 24

- Albert Frederick Pollard, "Seymour, Edward (1539?–1621)", Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, Volume 51(1897).

- ^ Historic England. "Amesbury Abbey (1131079)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- Historic England. "Amesbury Abbey (park and garden) (1000469)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

51°10′19″N 1°47′03″W / 51.1719°N 1.7843°W / 51.1719; -1.7843

Categories:- Amesbury Abbey

- 979 establishments

- Monasteries in Wiltshire

- Order of Fontevraud

- Anglo-Saxon monastic houses

- Benedictine monasteries in England

- Benedictine nunneries in England

- Christian monasteries established in the 10th century

- Christian monasteries disestablished in the 12th century

- 10th-century establishments in England

- 1177 disestablishments in England