| Revision as of 15:38, 7 September 2015 editOrenburg1 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users166,239 editsm sp← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:37, 28 October 2024 edit undoAbsolutiva (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,603 edits WP:BOLDITISTag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| (531 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| ]; sex offender-free districts appeared as a result of ].]] | |||

| {{Sex offender registries in the United States}} | |||

| '''Sex offender registries in the United States''' consists of federal and state level ] designed to collect information of persons convicted of sexual offenses for law enforcement and public notification purposes. All 50 states and District of Columbia maintain sex offender registries that are open to public via sex offender registration websites, although some registered ]s are visible to law enforcement only. According to ], as of 2015 there were 843,260 registered sex offenders in United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.missingkids.com/en_US/documents/Sex_Offenders_Map.pdf|title=Map of Registered Sex Offenders in the United States|publisher=National Center for Missing and Exploited Children|accessdate=2015-08-21}}</ref> | |||

| In the United States, ] existed at both the federal and state levels. The federal registry is known as the National Sex Offender Public Website (NSOPW) and integrates data in all state, territorial, and tribal registries provided by offenders required to register.<ref name=nsopw>{{cite web|url=https://www.nsopw.gov/about-nsopw|title=Dru Sjodin National Sex Offender Public Website|publisher=]|access-date=2024-03-03|date=2023-08-16}}</ref> Registries contain information about persons convicted of sexual offenses for law enforcement and public notification purposes. All 50 ] and the ] maintain sex offender registries that are open to the public via websites; most information on offenders is visible to the public. Public disclosure of offender information varies between the states depending on offenders' designated tier, which may also vary from state to state, or risk assessment result. According to ], as of 2016 there were 859,500 registered ]s in United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.missingkids.com/en_US/documents/Sex_Offenders_Map.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170717203105/http://www.missingkids.com/en_US/documents/Sex_Offenders_Map.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=2017-07-17|title=Map of Registered Sex Offenders in the United States|publisher=National Center for Missing and Exploited Children|access-date=2016-01-07}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit}} | |||

| The majority of states and the federal government apply systems based on conviction offenses only, where registration requirement is triggered as a consequence of finding of guilt, or pleading guilty, to a sex offense regardless of the actual gravity of the crime. The trial judge typically can not exercise ] concerning registration.<ref name=Widening>{{cite journal|last1=Harris|first1=A. J.|last2=Lobanov-Rostovsky|first2=C.|last3=Levenson|first3=J. S.|title=Widening the Net: The Effects of Transitioning to the Adam Walsh Act's Federally Mandated Sex Offender Classification System|journal=Criminal Justice and Behavior|date=2 April 2010|volume=37|issue=5|pages=503–519|doi=10.1177/0093854810363889|s2cid=55988358|url=http://ww.ilvoices.com/media/ea99d28960ec776bffff84baffffe415.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150930182129/http://ww.ilvoices.com/media/ea99d28960ec776bffff84baffffe415.pdf|archive-date=30 September 2015}}</ref>{{POV statement||date=November 2015}} Depending on jurisdiction, offenses requiring registration range in their severity from public urination or adolescent sexual experimentation with peers, to violent sex offenses. In some states offenses such as unlawful imprisonment may require sex offender registration.<ref>{{cite news|title=Court keeps man on sex offender list but says 'troubling'|url=http://www.toledonewsnow.com/story/28639772/court-keeps-man-on-sex-offender-list-but-says-troubling|work=Toledo News|date=28 March 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402110328/http://www.toledonewsnow.com/story/28639772/court-keeps-man-on-sex-offender-list-but-says-troubling|archive-date=2 April 2015}}</ref> According to ], children as young as 9 have been placed on the registry;<ref name=HRW2> (2012) ] {{ISBN|978-1-62313-0084}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/when-kids-are-sex-offenders/|title=When Kids Are Sex Offenders|publisher=Boston Review|date=20 September 2013|access-date=1 September 2023}}</ref> ]s account for 25 percent of registrants.<ref name="senseless">{{cite news |last1=Lehrer |first1=Eli |date=7 September 2015 |title=A Senseless Policy - Take kids off the sex-offender registries. |url=http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/senseless-policy_1020694.html?page=2 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150902000211/http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/senseless-policy_1020694.html?page=2 |archive-date=2 September 2015 |access-date=1 September 2015 |work=The Weekly Standard}}</ref> In some states, the length of the registration period is determined by the offense or ]; in others all registration is for life.<ref name=Klaas>{{cite web|url=http://klaaskids.org/megans-law/|title=Megan's Law by State|publisher=Klaas Kids Foundation|access-date=2015-08-21|date=2014-04-14}}</ref> Some states allow removal from the registry under certain specific, limited circumstances.<ref name=Klaas/> Information of juvenile offenders is withheld for law enforcement but may be made public after their 18th birthday.<ref name="Center for Sex Offender Management">{{cite web|title=How do Registration Laws Apply to Juvenile Offenders in Different States?|url=http://www.csom.org/train/juvenile/7/7_4.htm|publisher=Center for Sex Offender Management}}</ref> | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| Registered sex offenders are required to periodically appear in person to their local law enforcement for purposes of collecting their personal information. Information collected usually includes, but is not limited to, ], ]s, ] including all ], ], ], ], ] and any identifying features of the registrant such as ]s and ]s. Information pertaining to physical description, vehicles, workplace and address are posted to public websites by responsible officials. In addition, registrants are often subject to presence and residency restrictions that bar sex offenders from working or living within exclusion zones that sometimes cover entire cities and force registrants to live on ] or under ]s.<ref>{{cite news|title=State Supreme Court overturns sex offender housing rules in San Diego; law could affect Orange County, beyond|url=http://www.ocregister.com/articles/offenders-652781-law-restrictions.html|work=The Orange County Register|date=2 March 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Miami Sex Offenders Live on Train Tracks Thanks to Draconian Restrictions|url=http://www.browardpalmbeach.com/news/miami-sex-offenders-live-on-train-tracks-thanks-to-draconian-restrictions-6353588|work=Broward Palm Beach New Times|date=13 March 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Miami sex offenders limited to life under a bridge|url=http://www.tampabay.com/features/humaninterest/miami-sex-offenders-limited-to-life-under-a-bridge/1027668|work=Tampa Bay Times|date=14 August 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Sex Offender Registration and Notification (SORN) has been studied for its impact on the rates of sexual offense recidivism, with the majority of studies demonstrating no impact.<ref>{{cite web|title=Adult Sex Offender Management|url=http://www.smart.gov/pdfs/AdultSexOffenderManagement.pdf|publisher=U.S. Department of Justice|ref=ASAM|page=3}}</ref> The ] has upheld sex offender registration laws both times such laws have been examined by them. Several challenges on parts of state level legislation have been honored by the courts. Legal scholars have challenged the rationale behind the Supreme Court rulings. Perceived problems in legislation has prompted organizations such as ], ], and ], among others, to promote reform. | |||

| ] professor ] has called the child safety zones ''“tantamount to practices of banishment”'' that he deems disproportionately harsh, noting that registries include not just the “worst of the worst” such as child rapists and violent repeat offenders but also ''“adults who supplied pornography to teenage minors; young schoolteachers who foolishly fell in love with one of their students; men who urinated in public, or were caught having sex in remote areas of public parks after dark.”''<ref name=tp>{{cite news|last1=Flatov|first1=Nicole|title=Inside Miami’s Hidden Tent City For ‘Sex Offenders’|url=http://thinkprogress.org/justice/2014/10/23/3583307/in-miami-dade-sex-offenders-are-relegated-to-outdoor-encampments/|work=Think Progress|date=23 October 2014}}</ref> In many instances, individuals have pleaded guilty to an offense like urinating in public decades ago, not realizing the result would be their placement on a sex offender registry, and all of the restrictions that come with it.<ref name=tp/> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Depending on jurisdiction, offenses requiring registration range in their severity from public urination or children and teens experimenting with their peers, to violent rape and predatory sexual murders involving children. In some states non-sexual offenses such as unlawful imprisonment may require sex offender registration.<ref>{{cite news|title=Court keeps man on sex offender list but says 'troubling'|url=http://www.toledonewsnow.com/story/28639772/court-keeps-man-on-sex-offender-list-but-says-troubling|work=Toledo News|date=28 March 2015|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20150402110328/http://www.toledonewsnow.com/story/28639772/court-keeps-man-on-sex-offender-list-but-says-troubling|archivedate=2 April 2015}}</ref> According to ], children as young as 9 have been placed on the registry for sexually experimenting with their peers.<ref name=HRW2> (2012) ] ISBN 978-1-62313-0084</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://bostonreview.net/blog/youth-sex-offender-registry-hrw|title=When Kids Are Sex Offenders|publisher=Boston Review|date=20 September 2013}}</ref> Juvenile convicts account for as much as 25 percent of the registrants.<ref name=senseless>{{cite news|last1=Lehrer|first1=Eli|title=A Senseless Policy - Take kids off the sex-offender registries.|url=http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/senseless-policy_1020694.html?page=2|accessdate=1 September 2015|work=The Weekly Standard|date=7 September 2015}}</ref> Federal ] encourages states to register juveniles by tying federal funding to state and local enforcement to the degree to which state registries comply with the law’s classification system for sex offenders.<ref name=senseless/> | |||

| In 1947, ] became the first state in the United States to have a sex offender registration program.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.meganslaw.ca.gov/sexreg.aspx?lang=ENGLISH|title=California Megan's Law – California Department of Justice – Office of the Attorney General<!-- Bot generated title -->|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151104223242/http://www.meganslaw.ca.gov/sexreg.aspx?lang=ENGLISH|archive-date=2015-11-04}}</ref> ] was prompted by the ] murder case to introduce a bill calling for the formation of a sex offender registry; California became the first U.S. state to | |||

| make this mandatory.<ref>{{cite book|last=Katz|first=Hélèna| year= 2010 | title=Cold Cases: Famous Unsolved Mysteries, Crimes, and Disappearances in America|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn= 978-0-313-37692-4 |page=190}}</ref> In 1990, ] state began community notification of its most dangerous sex offenders, making it the first state to ever make any sex offender information publicly available. Prior to 1994, only a few states required convicted sex offenders to register their addresses with local law enforcement. The 1990s saw the emergence of several cases of brutal violent sexual offenses against children. Crimes like those of ], ] and ] were highly publicized. As a result, public policies began to focus on protecting public from ].<ref name=wright>{{cite book|last1=Wright|first1=Ph.D Richard G.|title=Sex offender laws : failed policies, new directions|date=2014|publisher=Springer Publishing Co Inc|isbn=9780826196712|pages=50–65|edition=Second|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ms75AwAAQBAJ}}</ref> Since the early 1990s, several state and federal laws, often named after victims, have been enacted as a response to public outrage generated by highly publicized, but statistically very rare,<ref name=NYtimes>{{cite news|last1=Lancaster|first1=Roger|title=Panic Leads to Bad Policy on Sex Offenders|url=https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/02/20/too-many-restrictions-on-sex-offenders-or-too-few/panic-leads-to-bad-policy-on-sex-offenders|access-date=26 November 2014|work=The New York Times|date=20 February 2013}}</ref> violent predatory sex crimes against children by strangers.<ref name=wright/> | |||

| ===Jacob Wetterling Act of 1994=== | |||

| States apply differing sets of criteria dictating which offenders are required to be listed on public databases. Some states use scientific risk assessment tools to determine the future risk of the offender and exclude low-risk offenders from public database. In some states, offenders are categorized according to the tier level related to the listed offense. Duration of registration vary usually from 10 years to life depending on the state legislation and tier/risk- category. Some states exclude low tier offenders from public registries while in others, all offenders are publicly listed.<ref name=Klaas>{{cite web|url=http://klaaskids.org/megans-law/|title=Megan’s Law by State|publisher=Klaas Kids Foundation|access-date=2015-08-21}}</ref> Some states offer possibility to petition to be removed from the registry under certain circumstances.<ref name=Klaas/> | |||

| {{main|Jacob Wetterling Act}} | |||

| In 1989, an 11-year-old boy, ], was abducted from a street in ]. His whereabouts remained unknown for nearly 27 years until remains were discovered just outside ], in 2016. Jacob's mother, ], current chair of ], led a community effort to implement a sex offender registration requirement in Minnesota and, subsequently, nationally. In 1994, Congress passed the ]. If states failed to comply, the states would forfeit 10% of federal funds from the ].{{POV statement||date=November 2015}} The act required each state to create a registry of offenders convicted of qualifying sex offenses and certain other offenses against children and to track offenders by confirming their place of residence annually for ten years after their release into the community or quarterly for the rest of their lives if the sex offender was convicted of a violent sex crime. States had a certain time period to enact the legislation, along with guidelines established by the ].<ref name=wright/>{{explain|date=November 2015}} The registration information collected was treated as private data viewable by law enforcement personnel only, although law enforcement agencies were allowed to release relevant information that was deemed necessary to protect the public concerning a specific person required to register.<ref>{{cite web|title=Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994|url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-103hr3355enr/pdf/BILLS-103hr3355enr.pdf|publisher=One Hundred Third Congress of the United States of America|pages=246–247|date=1995}}</ref> Another high-profile case, abuse and ] led to modification of Jacob Wetterling Act.<ref name=wright/> The subsequent laws forcing changes to the sex offenders registries in all 50 states have since troubled Patty Wetterling and she has been vocal about her opposition to including children on the registry as well as allowing full access to the public. In an interview with reporter Madeleine Baran, Wetterling stated, "No more victims, that's the goal. But we let our emotions run away from achieving that goal." In lamenting how we treat sex offenders she stated, "You're screwed. You will not get a job, you will not find housing. This is on your record forever, good luck." She believes that by not allowing sex offenders who have served their time to reintegrate to society we do more harm than good, "I've turned 180 from where I was." <ref>{{cite podcast |url=https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/id1148175292 |title=In the dark|publisher= American Public Media |host= Madeleine Baran |date= October 3, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Majority of states apply systems based on conviction offenses only, where sex offender registration is mandatory if person pleads or is found guilty of violating any of the listed offenses, regardless the nature of the offense or offender. Under these systems, sentencing judge does not sentence convict into sex offender registry. Instead, registration is mandatory ] arising from conviction under one of the qualifying offenses. Therefore, sentencing judge ''can not'' usually use ] and forgo registration requirement, even if he thinks the registration would be unreasonable taking account possible mitigating factors pertaining to individual cases.<ref name=Widening>{{cite journal|last1=Harris|first1=A. J.|last2=Lobanov-Rostovsky|first2=C.|last3=Levenson|first3=J. S.|title=Widening the Net: The Effects of Transitioning to the Adam Walsh Act's Federally Mandated Sex Offender Classification System|journal=Criminal Justice and Behavior|date=2 April 2010|volume=37|issue=5|pages=503–519|doi=10.1177/0093854810363889}}</ref> Due to this feature, laws target wide range of behaviors and tend to treat all offenders the same. Civil right groups,<ref name=HRW2/><ref>{{cite web|last1=Jacobs|first1=Deborah|title=Why Sex Offender Laws Do More Harm Than Good|url=https://www.aclu-nj.org/theissues/criminaljustice/whysexoffenderlawsdomoreha/|accessdate=14 November 2014|agency=American Civil Liberties Union|ref=aclu}}</ref> law reform activist,<ref>{{cite news|last1=Lovett|first1=Ian|title=Restricted Group Speaks Up, Saying Sex Crime Measures Go Too Far|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/02/us/restricted-group-speaks-up-saying-sex-crime-measures-go-too-far.html|publisher=The New York Times|date=October 1, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Ulmer|first1=Nick|title=Taking a Stand: Women Against Registry responds to our 14 News investigation|url=http://www.14news.com/story/24789519/taking-a-stand-women-against-registry-respond-to-our-14-news-investigation|work=14News|agency=NBC|date=21 February 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Rowan|first1=Shana|title=My Word: Forget broad brush for sex offenders|url=http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/2013-07-14/news/os-ed-myword-sex-offenders-20130713_1_registry-laws-jessica-lunsford-john-evander-couey|accessdate=17 November 2014|work=Orlando Sentinel|date=14 July 2013}}</ref> academics,<ref name=Levenson1>{{cite news|last1=Levenson|first1=Jill|title=Does youthful mistake merit sex-offender status?|url=http://edition.cnn.com/2015/08/06/opinions/levenson-sex-offender-registry-reform/|work=cnn.com|date=6 August 2015}}</ref><ref name=atsa1>{{cite web|title=RE: Pending Sex Offender Registry Legislation (HR 4472)|url=http://www.atsa.com/pdfs/Policy/responseHR4472.pdf|ref=Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150902205155/http://www.atsa.com/pdfs/Policy/responseHR4472.pdf|archivedate=2 September 2015|date=8 August 2005}}</ref> some child safety advocates,<ref name=wetterling>{{cite news|title=Patty Wetterling questions sex offender laws|url=http://www.citypages.com/2013-03-20/news/patty-wetterling-questions-sex-offender-laws/full/|accessdate=13 November 2014}}</ref><ref name=SacBee_2007_09_14>{{cite web|url=http://www.sacbee.com/110/story/377462.html | title=Patty Wetterling: The harm in sex-offender laws | author=Patty Wetterling | publisher='']'' | archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20071014073510/http://sacbee.com/110/story/377462.html | archivedate=14 October 2007}}</ref><ref name=wetterling2>{{cite news|last1=Gunderson|first1=Dan|title=Sex offender laws have unintended consequences|url=http://www.mprnews.org/story/2007/06/11/sexoffender1|accessdate=16 November 2014|work=MPR news|date=18 June 2007}}</ref><ref name=slate>{{cite news|last1=Mellema|first1=Matt|title=Sex Offender Laws Have Gone Too Far|url= http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2014/08/sex_offender_registry_laws_have_our_policies_gone_too_far.html|accessdate=16 November 2014|work=Slate|date=11 August 2014}}</ref><ref name=slate2>{{cite news|last1=Sethi|first1=Chanakya|title=Reforming the Registry|url=http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2014/08/sex_offender_registries_the_best_ideas_for_reforming_the_law.html|accessdate=16 November 2014|work=Slate|date=15 August 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Wright|first1=Richard|title=Sex Offender Laws: Failed Policies, New Directions|date=16 March 2009|publisher=Springer Publishing Company|location=New York|isbn=978--0-8261-1109-8|pages=101–116|url=http://sexoffenderissues.blogspot.fi/2009/04/interview-with-patty-wetterling-june-27.html|accessdate=16 November 2014|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150710221615/http://sexoffenderissues.blogspot.fi/2009/04/interview-with-patty-wetterling-june-27.html|archivedate=10 July 2015}}</ref> politicians<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Meloy|first1=Michelle|last2=Curtis|first2=Kristin|last3=Boatwright|first3=Jessica|title=Policy-makers’ perceptions on their sex offender laws: the good, the bad, and the ugly|journal=Criminal Justice Studies: A CriticalJournal of Crime, Law and Society|date=23 Nov 2012|volume=26|issue=1|doi=10.1080/1478601.2012.744307|quote="Therefore, state-level policy-makers from across the country, who sponsored and passed at least one sex offender law in their state, (n = 61) were interviewed about sex offenders and sex crimes. Policy-makers believe sex offender laws are too broad. The laws extend to nonviolent offenses, low-risk offenders, and thus dilute the law enforcement potency of sex offender registries."}}</ref> and law enforcement officials<ref name=SFGate>{{cite news|title=Board wants to remove low-risk sex offenders from registry|url=http://www.sfgate.com/crime/article/Board-wants-to-remove-low-risk-sex-offenders-from-5503219.php|work=SFGate|date=25 May 2014}}</ref> think that current laws have become too broad and often target wrong people swaying attention of the public and law enforcement away from potentially dangerous high-risk sex offenders, while severely impacting lives of offenders,<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Levenson|first1=J. S.|title=The Effect of Megan's Law on Sex Offender Reintegration|journal=Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice|date=1 February 2005|volume=21|issue=1|pages=49–66|doi=10.1177/1043986204271676}}</ref><ref name=impact3>{{cite journal|last1=Tewksbury|first1=R.|title=Collateral Consequences of Sex Offender Registration|journal=Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice|date=1 February 2005|volume=21|issue=1|pages=67–81|doi=10.1177/1043986204271704}}</ref><ref name=impact2>{{cite journal|last1=Mercado|first1=C. C.|last2=Alvarez|first2=S.|last3=Levenson|first3=J.|title=The Impact of Specialized Sex Offender Legislation on Community Reentry|journal=Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment|date=1 June 2008|volume=20|issue=2|pages=188–205|doi=10.1177/1079063208317540}}</ref><ref name=impact1>{{cite journal|last1=Levenson|first1=Jill S.|last2=D'Amora|first2=David A.|last3=Hern|first3=Andrea L.|title=Megan's law and its impact on community re-entry for sex offenders|journal=Behavioral Sciences & the Law|date=July 2007|volume=25|issue=4|pages=587–602|doi=10.1002/bsl.770}}</ref> and their families,<ref name=collateral>{{cite news|last1=Balko|first1=Radley|title=The collateral damage of sex offender laws|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2015/08/28/the-collateral-damage-of-sex-offender-laws/|work=The Washington Post|date=28 August 2015}}</ref><ref name=collateral2>{{cite news|last1=Yoder|first1=Steven|title=Collateral damage: Harsh sex offender laws may put whole families at risk|url=http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/8/27/harsh-sex-offender-laws-may-put-whole-families-at-risk.html|work=Al Jazeera America|date=27 August 2015}}</ref> attempting to re-integrate to society. | |||

| ===Megan's Law of 1996=== | |||

| The ] has upheld sex offender registration laws twice, in two respects. Several challenges to some parts of state level sex offender laws have succeeded, however. | |||

| {{main|Megan's Law}} {{see also|International Megan's Law}} | |||

| ]; sex offender-free districts appeared as a result of ].]] | |||

| ==Brief history of major laws== | |||

| In 1947, California became the first state in the United States to have a sex offender registration program.<ref></ref> In 1990, ] began community notification of its most dangerous sex offenders, making it the first state to ever make any sex offender information publicly available. Prior 1994 only few states required convicted sex offenders to register addresses with local law enforcement. The 1990s saw the emergence of several cases of brutal violent sexual offenses against children. Heinous crimes like those of ], ] and ] were highly publicized. As a result, public policies began to focus on protecting public from ].<ref name=wright>{{cite book|last1=Wright|first1=Ph.D Richard G.|title=Sex offender laws : failed policies, new directions|date=2014|publisher=Springer Publishing Co Inc|isbn=9780826196712|pages=50-65|edition=Second edition.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ms75AwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> Since early 1990s, several state and federal laws, often named after victims, have been enacted as a response to public outrage generated by highly publicized, but statistically very rare,<ref name=NYtimes>{{cite news|last1=Lancaster|first1=Roger|title=Panic Leads to Bad Policy on Sex Offenders|url=http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/02/20/too-many-restrictions-on-sex-offenders-or-too-few/panic-leads-to-bad-policy-on-sex-offenders|accessdate=26 November 2014|work=The New York Times|date=20 February 2013}}</ref> violent predatory sex crimes against children by strangers.<ref name=wright/> | |||

| Several scholars have referred the public outrage and fear following rare but high-profile predatory sex crimes as ] or public ]. Responding to this moral panic has been seen as reason why politicians have crafted one-size-fits-all solutions that contradict with policy recommendations of scientific research and has lead to current state of broad registration and community notification, and residency and presence restriction schemes.<ref name=wright/><ref name=NYtimes/><ref>{{cite book|last1=Lancaster|first1=Roger N.|title=Sex panic and the punitive state|date=2011|publisher=University of California Press|location=CA|isbn=9780520262065|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VRLpP1V8_2YC&printsec=frontcover&dq}}</ref><ref name=Fox>{{cite journal|last1=Fox|first1=Kathryn J.|title=Incurable Sex Offenders, Lousy Judges & The Media: Moral Panic Sustenance in the Age of New Media|journal=American Journal of Criminal Justice|date=28 February 2012|volume=38|issue=1|pages=160–181|doi=10.1007/s12103-012-9154-6|url=http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12103-012-9154-6|issn=1936-1351}}</ref><ref name=Extein>{{cite news|last1=Extein|first1=Andrew|title=Fear the Bogeyman: Sex Offender Panic on Halloween|url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/andrew-extein-msw/fear-the-bogeyman-sex-off_b_4161136.html|accessdate=26 November 2014|work=Huffington Post|date=25 October 2013}}</ref><ref name=UniNebraska>{{cite web|last1=Spohn|first1=Ryan|title=Nebraska Sex Offender Registry Study Final Report|url=http://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/750534/ne-sex-offender-recidivism-report2.pdf|pages=51|publisher=University of Nebraska - Omaha|accessdate=21 November 2014|page=51|date=31 July 2013|archiveurl=http://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/750534/ne-sex-offender-recidivism-report2.pdf|archivedate=5 September 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hier|first1=S. P.|title=Thinking beyond moral panic: Risk, responsibility, and the politics of moralization|journal=Theoretical Criminology|date=1 May 2008|volume=12|issue=2|pages=173–190|doi=10.1177/1362480608089239|url=http://tcr.sagepub.com/content/12/2/173.short}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Maguire|first1=Mary|last2=Singer|first2=Jennie Kaufman|title=A False Sense of Security: Moral Panic Driven Sex Offender Legislation|journal=Critical Criminology|date=4 December 2010|volume=19|issue=4|pages=301–312|doi=10.1007/s10612-010-9127-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Zgoba|first1=Kristen M.|title=Spin doctors and moral crusaders: the moral panic behind child safety legislation|journal=Criminal Justice Studies|date=December 2004|volume=17|issue=4|pages=385–404|doi=10.1080/1478601042000314892|url=http://nj.gov/corrections/pdf/REU/Moral_Panic.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Meloy|first1=Michelle L.|last2=Miller|first2=Susan L.|last3=Curtis|first3=Kristin M.|title=Making Sense out of Nonsense: The Deconstruction of State-Level Sex Offender Residence Restrictions|journal=American Journal of Criminal Justice|date=10 June 2008|volume=33|issue=2|pages=209–222|doi=10.1007/s12103-008-9042-2}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Douard|first1=John|title=Sex Offender as Scapegoat: The Monstrous Other Within|journal=New York Law School Law Review|date=2009|volume=53|url=http://www.nylslawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2013/11/53-1.Douard.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Spencer|first1=D.|title=Sex offender as homo sacer|journal=Punishment & Society|date=1 April 2009|volume=11|issue=2|pages=219–240|doi=10.1177/1462474508101493}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Meloy|first1=Michelle L.|last2=Saleh|first2=Yustina|last3=Wolff|first3=Nancy|title=Sex Offender Laws in America: Can Panic‐Driven Legislation ever Create Safer Societies?|journal=Criminal Justice Studies|date=December 2007|volume=20|issue=4|pages=423–443|doi=10.1080/14786010701758211}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Sample|first1=Lisa. L.|last2=Evans|first2=Mary. K.|last3=Anderson|first3=Amy. L.|title=Sex Offender Community Notification Laws: Are Their Effects Symbolic or Instrumental in Nature?|journal=Criminal Justice Policy Review|date=18 June 2010|volume=22|issue=1|pages=27–49|doi=10.1177/0887403410373698}}</ref> | |||

| ===Jacob Wetterling Act of 1994=== | |||

| {{main|Jacob Wetterling Act}} | |||

| In 1989, a 11-year-old boy, ], was abducted from street in ]. Even tough it is not known who abducted Jacob, many assumed the perpetrator to be one of the sex offenders living in a halfway house in St. Joseph. Jacob's mother, ], current chair of ] lead the community effort to implement sex offender registration requirement in Minnesota and, subsequently, nationally. In 1994, Congress passed the ]. If states failed to comply, the states would forfeit 10% of federal funds from the ]. The act required each state to create registry of offenders convicted of qualifying sexual offenses and certain other offenses against children, to track known offenders by confirming their place of residence annually for ten years after their release into the community or quarterly for the rest of their lives if the sex offender was convicted of a violent sex crime. States had certain time period to enact the legislation, along with guidelines established by the ].<ref name=wright/> The registration information collected by was treated as private data for law enforcement purposes only, although law enforcement agencies were allowed to release relevant information that is necessary to protect the public concerning a specific person required to register.<ref>{{cite web|title=Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994|url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-103hr3355enr/pdf/BILLS-103hr3355enr.pdf|publisher=One Hundred Third Congress of the United States of America|pages=246-247|date=1995}}</ref> Another high-profile case, abuse and murder of ] led to modification of Jacob Wetterling Act. <ref name=wright/> | |||

| In 1994, 7-year-old ] from ] was raped and killed by a recidivist ]. Jesse Timmendequas, who had been convicted of two previous sex crimes against children, lured Megan in his house and raped and killed her. Megan's mother, Maureen Kanka, started to lobby to change the laws, arguing that registration established by the Wetterling Act was insufficient for community protection. Maureen Kanka's goal was to mandate community notification, which under the Wetterling Act had been at the discretion of law enforcement. She said that if she had known that a sex offender lived across the street, Megan would still be alive. In 1994, ] enacted ]. In 1996, President ] enacted a federal version of Megan's Law, as an amendment to the Jacob Wetterling Act. The amendment required all states to implement Registration and Community Notification Laws by the end of 1997. Prior to Megan's death, only 5 states had laws requiring sex offenders to register their personal information with law enforcement. On August 5, 1996 ] was the last state to enact its version of Megan's Law.<ref name=wright/> | |||

| ], has since removed her support for current laws and has openly criticized the evolution of sex offender registration and management laws in the United States since the Jacob Wetterling Act was passed, saying that the ''"registries have been hi-jacked"''. She says, laws are often applied to too many offenses and that the severity of the laws often makes it difficult to rehabilitate offenders.<ref name=SacBee_2007_09_14/><ref name=wetterling/><ref name=<ref name=wetterling2/><ref name=slate/><ref name=slate2/> | |||

| === |

===Amber Hagerman Child Protection Act Law of 1996=== | ||

| President ] signed the Amber Hagerman Child Protection Act Law into law in October 1996, creating the ] system and the national sex offender registry.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.salem-news.com/articles/january052010/amber_bus.php|title=14 Years After Her Daughter's Death, Donna Norris is Still Protecting Children|publisher=Salem-News|date=January 5, 2010|accessdate=March 17, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://definitions.uslegal.com/a/amber-hangerman-child-protection-act/|title=Amber Hangerman Child Protection Act Law and Legal Definition|publisher=uslegal.com|access-date=17 March 2023|date=17 March 2023}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Megan's Law}} | |||

| In 1994, 7-year-old ] from ] was raped and killed by recidivist ]. Jesse Timmenquas, who had been convicted of two previous sex crimes against children, lured Megan in his house and raped and killed her. Megan's mother, Maureen Kanka, started to lobby to change the laws, arguing that registration established by the Wetterling Act, was not a sufficient form of community protection. Her goal was to mandate community notification, which under the Wetterling Act had been at the discretion of law enforcement. She said that if she had known that sex offender lived across the street, Megan would still be alive. In 1996, ] enacted ]. In 1996, President ] enacted federal version of Megan's Law. The federal Megan's Law was a subsection of Jacob Wetterling Act. The two acts required all states to implement Registration and Community Notification Laws by the end of 1997. Prior to Megan's death, only 5 states had laws requiring sex offenders to register their personal information with law enforcement. On August 5, 1996 ] was the last state to enact its version of Megan's Law.<ref name=wright/> | |||

| ===Adam Walsh Act of 2006=== | ===Adam Walsh Act of 2006=== | ||

| {{main|Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act}} | {{main|Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act}} | ||

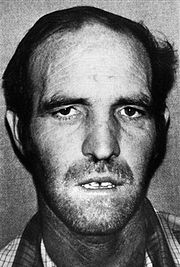

| ]; evidence indicated he killed Adam Walsh, and he confessed but then recanted.]] | |||

| The most comprehensive legislation related to the supervision and management of sex offenders is the ], named after ], who was kidnapped from a ] shopping mall and killed in 1981, when he was 6 |

The most comprehensive legislation related to the supervision and management of sex offenders is the ] (AWA), named after ], who was kidnapped from a ] shopping mall and killed in 1981, when he was 6 years old. The AWA was signed on the 25th anniversary of his abduction; efforts to establish a national registry was led by ], Adam's father. | ||

| One of the significant component of the AWA is the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA). SORNA provides uniform minimum guidelines for registration of sex offenders, regardless of the state they live in. SORNA requires states to widen the number of covered offenses and to include certain classes of juvenile offenders. Prior to SORNA, states were granted latitude in the methods to differentiate offender management levels. Whereas many states had adopted to use structured ] classification to distinguish "high risk" from "low risk" individuals, SORNA mandates such distinctions to be made solely on the basis of the governing offense.<ref name=AWA_state_survey>{{cite journal|last1=Harris|first1=A. J.|last2=Lobanov-Rostovsky|first2=C.|title=Implementing the Adam Walsh Act's Sex Offender Registration and Notification Provisions: A Survey of the States|journal=Criminal Justice Policy Review|date=22 September 2009|volume=21|issue=2|pages=202–222|doi=10.1177/0887403409346118|s2cid=144231914}}</ref> States are allowed, and often do, exceed the minimum requirements. Scholars have warned that classification system required under Adam Walsh Act is less sophisticated than risk-based approach previously adopted in certain states.<ref name=Widening/><ref name=wright/><ref name=perpetual_panic>{{cite journal|last1=O'Hear|first1=Michael M.|title=Perpetual Panic|journal=Federal Sentencing Reporter|date=2008|volume=21|issue=1|pages=69–77|doi=10.1525/fsr.2008.21.2.69|url=http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1114&context=facpub}}</ref> | |||

| As of April 2014, the ] reports that only 17 states, three territories and 63 tribes had substantially implemented requirements of the Adam Walsh Act.<ref>{{cite web|title=Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act Compliance News|url=http://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/adam-walsh-child-protection-and-safety-act.aspx|publisher=National Conference of State Legislatures}}</ref> | |||

| Extension in number of covered offenses and making the amendments apply ] under SORNA requirements expanded the registries by as much as 500% in some states.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Grinberg|first1=Emanuella|title=5 years later, states struggle to comply with federal sex offender law|url=http://edition.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/07/28/sex.offender.adam.walsh.act/|work=CNN|date=28 July 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ==Exclusion zones== | |||

| All states were required to comply with SORNA minimum guidelines by July 2009 or risk losing 10% of their funding through the ].<ref name=wright/>{{POV statement||date=November 2015}} {{As of|2014|April}}, the ] reports that only 17 states, three territories and 63 tribes had substantially implemented requirements of the Adam Walsh Act.<ref>{{cite web|title=Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act Compliance News|url=http://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/adam-walsh-child-protection-and-safety-act.aspx|publisher=National Conference of State Legislatures}}</ref> | |||

| {{Expand section|date=September 2015}} | |||

| In 2006, California voters passed Proposition 83, which will enforce "lifetime monitoring of convicted sexual predators and the creation of predator free zones".<ref></ref><ref> Sex Offenders. Sexually violent predators. Punishment, residence restrictions and monitoring. Initiative Statute.</ref> This proposition was challenged the next day in federal court on grounds relating to ''ex post facto''. The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, ], found that Proposition 83 did not apply retroactively. | |||

| ==Registration== | |||

| ==Constitutionality== | |||

| Registration and Community Notification Laws have been challenged on a number of constitutional and other bases, generating substantial amount of case law. Those challenging the statutes have claimed violations of ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name=wright/> | |||

| ===U.S. Supreme Court rulings=== | |||

| In two cases docketed for argument on 13 November 2003, the sex offender registries of two states, Alaska and Connecticut, would face legal challenge. This was the first instance that the Supreme Court had to examine the implementation of sex offender registries in throughout the U.S. The ruling would let the states know how far they could go in informing citizens of perpetrators of sex crimes. In '']'' (2002) the ] affirmed this public disclosure of sex offender information.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.abanet.org/publiced/preview/school/sexoffenders0203.html|title=Supreme Court Cases of Interest 2002–2003: Sex Offender Registries (ABA Division for Public Education) | |||

| |publisher=www.abanet.org|accessdate=2008-03-16}}</ref><ref name=findlaw> | |||

| {{cite web|url=http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=CASE&court=US&vol=538&page=1 | |||

| |title=Connecticut Department of Public Safety, et al., Petitioners v. John Doe, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated|publisher=caselaw.lp.findlaw.com|accessdate=2008-03-15}}</ref> | |||

| Sex offenders must periodically report in person to their local law enforcement agency and furnish their address, and list of other information such as place of employment and email addresses. The offenders are photographed and fingerprinted by law enforcement, and in some cases ] information is also collected. Registration period depends on the classification level and the law of the governing jurisdiction. | |||

| ====''Ex post facto'' challenge==== | |||

| In '']'', 538 U.S. 84 (2003), the Supreme Court upheld ]'s sex-offender registration ]. Reasoning that sex offender registration deals with ], not punishment, the Court ruled 6–3 that it is not an ] ]. Justices ], ], and ] dissented. | |||

| ==Classification of offenders== | |||

| in '']'', Supreme Court No. S-12944, Court of Appeals No. A-09623, Superior Court No. 1KE-05-00765 C | |||

| O P I N I O N | |||

| can be found in its entirety here:<ref>http://www.courtrecords.alaska.gov/webdocs/opinions/ops/sp-6897.pdf</ref> | |||

| No. 6897 - April 25, 2014 | |||

| States apply varied methods of classifying registrants. Identical offenses committed in different states may produce different outcomes in terms of public disclosure and registration period. An offender classified as level/tier I offender in one state, with no public notification requirement, might be classified as tier II or tier III offender in another. Sources of variation are diverse, but may be viewed over three dimensions — how classes of registrants are distinguished from one another, the criteria used in the classification process, and the processes applied in classification decisions.<ref name=Widening/> | |||

| 29 April 2014, The Alaska Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a 62-year-old Ketchikan man who had been found guilty in 2006 of failure to register as a sex offender. | |||

| The first point of divergence is how states distinguish their registrants. At one end are the states operating single-tier systems that treat registrants equally with respect to reporting, registration duration, notification, and related factors. Alternatively, some states use multi-tier systems, usually with two or three categories that are supposed to reflect presumed public safety risk and, in turn, required levels of attention from law enforcement and the public. Depending on state, registration and notification systems may have special provisions for juveniles, habitual offenders or those deemed "]" by virtue of certain standards.<ref name=Widening/> | |||

| In its 25 April opinion, the court writes that the original offense for which Byron Charles was convicted occurred in the 1980s, before the State of Alaska passed the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act. That 1994 law required convicted sex offenders to register with the state, even if the offense took place before 1994. | |||

| The second dimension is the criteria employed in the classification decision. States running offense-based systems use the conviction offense or the number of prior offenses as the criteria for tier assignment. Other jurisdictions utilize various ] that consider factors that scientific research has linked to sexual ] risk, such as age, number of prior sex offenses, victim gender, relationship to the victim, and indicators of ] and ]. Finally, some states use a hybrid of offense-based and risk-assessment-based systems for classification. For example, ] law requires minimum terms of registration based on the conviction offense for which the registrant was convicted or adjudicated but also uses a risk assessment for identifying ]s — a limited population deemed to be dangerous and subject to more extensive requirements.<ref name=Widening/> | |||

| In 2008, the Alaska Supreme Court ruled in Doe v. State that the sex offender registration act cannot be applied retroactively. Charles had previously appealed his conviction on the failure to register charge, but had not argued against the retroactive clause in state law. After the court’s 2008 decision, though, Charles added that argument to his appeal. | |||

| Third, states distinguishing among registrants use differing systems and processes in establishing tier designations. In general, offense-based classification systems are used for their simplicity and uniformity. They allow classification decisions to be made via administrative or judicial processes. Risk-assessment-based systems, which employ actuarial risk assessment instruments and in some cases clinical assessments, require more of personnel involvement in the process. Some states, like Massachusetts and Colorado, utilize multidisciplinary review boards or ] to establish registrant tiers or sexual predator status.<ref name=Widening/> | |||

| Lower courts ruled that Charles had essentially waived his right to use that argument by not bringing it up earlier. But in its 25 April decision, the Supreme Court decided otherwise. | |||

| In some states, such as Kentucky, Florida, and Illinois, all sex offenders who move into the state and are required to register in their previous home states are required to register for life, regardless of their registration period in previous residence.<ref name=Kentucky>{{cite web|url=http://www.kentuckystatepolice.org/sor.htm#faq |title=Frequently}}</ref> Illinois reclassifies all registrants moving in as a "Sexual Predator". | |||

| The court writes that "permitting Charles to be convicted of violating a criminal statute that cannot constitutionally be applied to him would result in manifest injustice." | |||

| ==Public notification== | |||

| With that in mind, the Alaska Supreme Court reversed Charles’ 2006 conviction of failure to register as a sex offender. | |||

| <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.krbd.org/2014/04/29/high-court-overturns-2006-conviction/|title=Alaska Supreme Court overturns 2006 conviction|publisher=}}</ref> | |||

| States apply differing sets of criteria to determine which registration information is available to the public. In a few states, a judge determines the risk level of the offender, or scientific risk assessment tools are used; information on low-risk offenders may be available to law enforcement only. In other states, all sex offenders are treated equally, and all registration information is available to the public on a state Internet site. Information of juvenile offenders are withheld for law enforcement but may be made public after their 18th birthday.<ref name="Center for Sex Offender Management"/> | |||

| ====Due process challenge==== | |||

| In '']'', 538 U.S. 1 (2003),<ref>.</ref> the Court ruled that ]'s sex-offender registration statute did not violate the ] of those to whom it applied, although the Court "expresses no opinion as to whether the State's law violates ] principles." | |||

| Under federal ], only ''tier I'' registrants may be excluded from public disclosure, with exemption of those convicted of "specified offense against a minor."<ref>{{cite web|title=Registry Requirement FAQs|url=http://www.smart.gov/faqs/faq_requirement.htm|publisher=Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending|access-date=4 December 2015}}</ref> Since SORNA merely sets the minimum set of rules the states must follow, many SORNA compliant states have opted to disclose information of all tiers.<ref name=Klaas/> | |||

| Update: Reynolds V. United States Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit No. 10–6549. '''Argued 3 October 2011 – Decided 23 January 2012''' "The Act does not require pre-Act offenders to register before the Attorney General validly specifies that the Act’s registration provisions apply to them." | |||

| Disparities in state legislation have caused some registrants moving across state lines becoming subject to public disclosure and longer registration periods under the destination state's laws.<ref name=picayune>{{cite news|last1=Daley|first1=Ken|title=Alabama sex offender files suit challenging Louisiana registry laws in federal court|url=http://www.nola.com/crime/index.ssf/2015/04/alabama_sex_offender_files_sui.html|work=The Times-Picayune|date=21 April 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150706112041/http://www.nola.com/crime/index.ssf/2015/04/alabama_sex_offender_files_sui.html|archive-date=6 July 2015}}</ref> These disparities have also prompted some registrants to move from one state to another in order to avoid stricter rules of their original state.<ref>{{cite news|title=Portland: Sex offender magnet?|url=http://portlandtribune.com/pt/9-news/128257-portland-sex-offender-magnet|work=Portland Tribune|date=14 February 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ===State Court rulings=== | |||

| == |

==Exclusion zones== | ||

| {{external media | |||

| After losing the constitutional challenge in the US Supreme Court in 2002 one of the two Doe's in the case committed suicide. The other Doe began a new challenge in the state courts. Per the ''ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY'' website: On 25 July 2008, Doe number two prevailed and the Alaska Supreme Court ruled that the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act’s registration violated the ex post facto clause of the state's constitution and ruled that the requirement does not apply to persons who committed their crimes before the act became effective on 10 August 1994.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dps.state.ak.us/sorweb/sorweb.aspx|title=Department of Public Safety Home|publisher=}}</ref> | |||

| | float = right | |||

| | width = 258px | |||

| | image1 = in ] prior to September 23, 2017. Red and orange highlights denoted the areas where certain registered sex offenders could not reside within the city<ref>{{cite web|title=Sex Offender Ordinance|url=http://city.milwaukee.gov/cityclerk/News-Slider/Sex-Offender-Ordinance.htm#.WgJFp2i0NPY|website=city.milwaukee.gov|language=en|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171108095949/http://city.milwaukee.gov/cityclerk/News-Slider/Sex-Offender-Ordinance.htm#.WgJFp2i0NPY|archive-date=2017-11-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Milwaukee Common Council votes to lift sex offender residency restrictions|url=http://www.jsonline.com/story/news/local/milwaukee/2017/09/06/milwaukee-common-council-votes-lift-sex-offender-residency-restrictions/638400001/|work=Milwaukee Journal Sentinel|date=6 September 2017|language=en}}</ref>] | |||

| }} | |||

| Laws restricting where registered sex offenders may live or work have become increasingly common since 2005.<ref name=proximity>{{cite journal|last1=Zandbergen|first1=P. A.|last2=Levenson|first2=J. S.|last3=Hart|first3=T. C.|title=Residential Proximity to Schools and Daycares: An Empirical Analysis of Sex Offense Recidivism|journal=Criminal Justice and Behavior|date=2 April 2010|volume=37|issue=5|pages=482–502|doi=10.1177/0093854810363549|s2cid=56267056}}</ref><ref name=fedprobation>{{cite journal|last1=Levenson|first1=Jill|last2=Zgoba|first2=Kristen|last3=Tewksbury|first3=Richard|title=Sex Offender Residence Restrictions: Sensible Policy or Flawed Logic?|journal=Federal Probation|volume=71|issue=3|pages=2|url=http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/fedpro71&div=4&id=&page=|year=2007}}</ref> At least 30 states have enacted statewide residency restrictions prohibiting registrants from living within certain distances of ]s, ]s, ]s, school ], or other places where children may congregate.<ref name=impact_residence_restrictions>{{cite journal|last1=Levenson|first1=J. S.|title=The Impact of Sex Offender Residence Restrictions: 1,000 Feet From Danger or One Step From Absurd?|journal=International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology|date=1 April 2005|volume=49|issue=2|pages=168–178|doi=10.1177/0306624X04271304|pmid=15746268|url=http://www.innovations.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/105331.pdf|citeseerx=10.1.1.489.5943|s2cid=42407834}}</ref> Distance requirements range from {{convert|500|to|2500|ft}}, but most start at least {{convert|1000|ft|abbr=on}} from designated boundaries. In addition, hundreds of counties and municipalities have passed local ordinances exceeding the state requirements,<ref name=impact_residence_restrictions/><ref name=HRW>{{cite web|title=No Easy Answers: Sex Offender Laws in the US|url=https://www.hrw.org/report/2007/09/11/no-easy-answers/sex-offender-laws-us|publisher=Human Right Watch|date=11 September 2007}}</ref> and some local communities have created exclusion zones around ], ]s, ]s, ], ]s, ]s or other "recreational facilities" such as ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s and gymnasiums, regardless of whether publicly or privately owned.<ref name=HRW/><ref name=banishment>{{cite journal|last1=Yung|first1=Corey R.|title=Banishment By a Thousand Laws: Residency Restrictions on Sex Offenders|journal=Washington University Law Review|date=January 2007|volume=85|page=101|url=http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=law_lawreview}}</ref> Although restrictions are tied to distances from areas where children may congregate, most states apply exclusion zones to offenders even though their crimes did not involve | |||

| children.<ref name=banishment/><ref name=malden>{{cite web|title=SECTION 7.24 RESTRICTIONS ON REGISTERED SEX OFFENDERS|url=http://www.cityofmalden.org/ordinances/section-724-restrictions-registered-sex-offenders/section-724-restrictions-registered-sex|publisher=City of Malden|access-date=6 October 2015}}</ref> In a 2007 report, ] identified only four states limiting restrictions to those convicted of sex crimes involving minors. The report also found that laws preclude registrants from ]s within restriction areas.<ref name=HRW/> In 2005, some localities in Florida banned sex offenders from public hurricane shelters during the ].<ref name=banishment/> In 2007, ]'s city council considered banning registrants from moving in the city.<ref>{{cite news|title=Tampa wants to keep sex offenders outside city limits|url=http://www.sptimes.com/2007/01/19/Hillsborough/Tampa_wants_to_keep_s.shtml|work=Tampa Bay Times|date=19 January 2007}}</ref> | |||

| Restrictions may effectively cover entire cities, leaving small "pockets" of allowed places of residency. Residency restrictions in ] in 2006 covered more than 97% of rental housing area in ].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Keegan|first1=Kyle|last2=Saavedra|first2=Tony|title=State Supreme Court overturns sex offender housing rules in San Diego; law could affect Orange County, beyond|url=http://www.ocregister.com/articles/offenders-652781-law-restrictions.html|work=The Orange County Register|date=2 March 2015}}</ref> In an attempt to ] registrants from living in communities, localities have built small "pocket parks" to drive registrants out of the area.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Suter|first1=Leanne|title='Pocket parks' leave sex offenders questioning where to live|url=http://abc7.com/archive/9029894/|work=ABC7|date=15 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Lovett|first1=Ian|title=Neighborhoods Seek to Banish Sex Offenders by Building Parks|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/10/us/building-tiny-parks-to-drive-sex-offenders-away.html?_r=0|work=The New York Times|date=9 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Jennings|first1=Angel|title=L.A. sees parks as a weapon against sex offenders|url=https://www.latimes.com/local/la-xpm-2013-feb-28-la-me-parks-sex-offenders-20130301-story.html|work=Los Angeles Times|date=28 February 2013}}</ref> In 2007, journalists reported that registered sex offenders were living under the ] in ] because the state laws and ] ordinances banned them from living elsewhere.<ref>{{cite news|title=Florida housing sex offenders under bridge|url=http://www.cnn.com/2007/LAW/04/05/bridge.sex.offenders/index.html|work=CNN|date=6 April 2007}}</ref><ref name=wp_colony>{{cite news|title=Laws to Track Sex Offenders Encouraging Homelessness|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/12/26/AR2008122601722.html|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=27 December 2008}}</ref> Encampment of 140 registrants is known as ].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Samuels|first1=Robert|title=Sex offenders seek housing after closing of camp under the Julia Tuttle Causeway|url=http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/2010-07-27/news/fl-tuttle-sex-offenders-20100727_1_residency-restrictions-offenders-housing|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100730114446/http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/2010-07-27/news/fl-tuttle-sex-offenders-20100727_1_residency-restrictions-offenders-housing|url-status=dead|archive-date=July 30, 2010|work=The Sun-Sentinel|date=27 July 2010}}</ref><ref name=colony>{{cite news|title=From Julia Tuttle bridge to Shorecrest street corner: Miami sex offenders again living on street|url=http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/news/crime-law/from-julia-tuttle-bridge-to-shorecrest-street-corn/nLhZz/|work=Palm Beach Post|date=12 March 2012}}</ref> The colony generated international coverage and criticism around the country.<ref name=colony/><ref>{{cite news|last1=Häntzschel|first1=Jörg|title=USA: Umgang mit Sexualstraftätern - Verdammt in alle Ewigkeit|url=http://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/usa-umgang-mit-sexualstraftaetern-verdammt-in-alle-ewigkeit-1.32920|work=Süddeutsche Zeitung|date=17 May 2010}}</ref> The colony was disbanded in 2010 when the city found acceptable housing in the area for the registrants, but reports five years later indicated that some registrants were still living on streets or alongside railroad tracks.<ref name=colony/><ref name=tracks>{{cite news|title=Miami Sex Offenders Live on Train Tracks Thanks to Draconian Restrictions|url=http://www.browardpalmbeach.com/news/miami-sex-offenders-live-on-train-tracks-thanks-to-draconian-restrictions-6353588|work=Broward Palm Beach New Times|date=13 March 2014}}</ref> As of 2013 ], was faced with a situation where 40 sex offenders were living in two cramped trailers, which were regularly moved between isolated locations around the county by the officials, due to local living restrictions.<ref name=NYT02413>{{cite news|title=In 2 Trailers, the Neighbors Nobody Wants|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/05/nyregion/suffolk-county-still-struggling-to-house-sex-offenders.html|access-date=5 February 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|date=4 February 2013|author=Michael Schwirtz}}</ref><ref name=NYT021707>{{cite news|title=Suffolk County to Keep Sex Offenders on the Move|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/17/nyregion/17sex.html|access-date=5 February 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|date=17 February 2007|author=Corey Kilgannon|quote=Now officials of this county on Long Island say they have a solution: putting sex offenders in trailers to be moved regularly around the county, parked for several weeks at a time on public land away from residential areas and enforcing stiff curfews.}}</ref> | |||

| ====California==== | |||

| The California Supreme Court ruled on 2 March 2015 that a state law barring sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of a school or park is unconstitutional.<ref>http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/02/sex-offenders-unconstitutional-california_n_6788268.html</ref> The ruling immediately affects only San Diego County, where the case originated. The court found that in San Diego County, the 2,000-feet rule meant that less than 3 percent of multi-unit housing was available to offenders. Additionally, federal law banned anyone in a state database of sex offenders from receiving federal housing subsidies after June 2001. | |||

| == |

==Effectiveness== | ||

| {{main|Effectiveness of sex offender registration policies in the United States}} | |||

| In the ruling of , and in 2000, The Supreme Court denied Florida's request for rehearing on the constitutionality of the 1995 sentencing guidelines due to the unconstitutionality being a violation of the "]," leaving the decision by the 2nd DCA to set precedence. It has opened a Pandora's box for Florida Legislature as many laws that were enacted violating Article III, section 6, Single subject rule are open to constitutional arguments. In the decision of Heggs, many laws which were enacted now face a constitutional argument as it is clear there is an unconstitutional, illegal and unlawful enactment of §943.0435, which was enacted in : Senate Bill 958. The Bill was related to the release of Public Records Information. | |||

| Evidence to support the effectiveness of public sex offender registries is limited and mixed.<ref name=somapi_sec1_ch8>{{cite web|author1=Office of Justice Programs|author-link1=Office of Justice Programs|title=Chapter 8: Sex Offender Management Strategies|url=http://www.smart.gov/SOMAPI/sec1/ch8_strategies.html|publisher=Office of Justice Programs - Sex Offender Management and Planning Initiative (SOMAPI)|date=2012}}</ref> Majority of research results do not find ] shift in sexual offense ] following the implementation of sex offender registration and notification (SORN) regimes.<ref name=collateral_family>{{cite journal|last1=Levenson|first1=Jill|last2=Tewksbury|first2=Richard|title=Collateral Damage: Family Members of Registered Sex Offenders|journal=American Journal of Criminal Justice|date=15 January 2009|volume=34|issue=1–2|pages=54–68|doi=10.1007/s12103-008-9055-x|url=http://www.csor-home.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Collateral-Damage-Family-Members-of-Registered-Sex-Offenders.pdf|citeseerx=10.1.1.615.3651|s2cid=146412299}}</ref><ref name=influence>{{cite journal|last1=Vasquez|first1=B. E.|last2=Maddan|first2=S.|last3=Walker|first3=J. T.|title=The Influence of Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws in the United States: A Time-Series Analysis|journal=Crime & Delinquency|date=26 October 2007|volume=54|issue=2|pages=175–192|doi=10.1177/0011128707311641|s2cid=53318656}}</ref><ref name=recidivism&reintegration>{{cite journal|last1=Zevitz|first1=Richard G.|title=Sex Offender Community Notification: Its Role in Recidivism and Offender Reintegration|journal=Criminal Justice Studies|date=June 2006|volume=19|issue=2|pages=193–208|doi=10.1080/14786010600764567|s2cid=144828566}}</ref><ref name=Prescott&Rockoff>{{cite journal|last1=Prescott|first1=J.J.|last2=Rockoff|first2=Jonah E.|title=Do Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws Affect Criminal Behavior?|journal=Journal of Law and Economics|date=February 2011|volume=54|issue=1|pages=161–206|doi=10.1086/658485|url=http://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1079&context=articles|citeseerx=10.1.1.363.1170|s2cid=1672265}}</ref> A few studies indicate that ] may have been lowered by SORN policies,<ref name=minnesota>{{cite journal|last1=DUWE|first1=GRANT|last2=DONNAY|first2=WILLIAM|title=The Impact of Megan's Law on Sex Offender Recidivism: The Minnesota Experience|journal=Criminology|date=May 2008|volume=46|issue=2|pages=411–446|doi=10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00114.x}}</ref><ref name=washington>{{cite web|title=Sex offender sentencing in Washington State: Has community notification reduced recidivism?|url=http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/919|publisher=Washington State Institute for Public Policy|date=December 2005}}</ref> while a few have found statistically significant increase in sex crimes following SORN implementation.<ref name=somapi_sec1_ch8/><ref name=SD>{{cite news|title=Studies question effectiveness of sex offender laws|url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/08/110830165016.htm|work=Science Daily|date=30 August 2011}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ]' SMART Office, sex offender registration and notification requirements arguably have been implemented in the absence of empirical evidence regarding their effectiveness.<ref name=somapi_sec1_ch8/> | |||

| According to SMART Office, there is no empirical support for the effectiveness of residence restrictions. In fact, a number of negative unintended consequences have been empirically identified that may aggravate rather than mitigate offender risk.<ref name=somapi_sec1_ch8/> | |||

| Florida legislature outlined Sex Offender Registration in the creation of , further in the Bill the single subject rule was violated when 1998 Credit Upon Resentence of an Offender Serving a Split Sentence, which has nothing in regards to the release of public records information as Legislature attempted to mask a cross reference correction. In the correction there was statutory language added in effort to bring it in compliance with the Florida Constitution and 3 subsections appeared in §921.0017, that were in regards to appropriation of funds. | |||

| ==Debate== | |||

| In the 1998 supplement where the new amendments and created laws would have been published. §921.0017 as well as were no where to be found. In great research the cross reference error in §921.0017 was the focus, and the added statutory language appears in an illegally and unlawfully enacted statute §921.243 that cites 97 – 299; Senate Bill 958; Florida chapter law 97-299 never creates §921.243, nor ever cites it for amendment and the 3 subsections dealing with appropriation of funds are being searched for within the 1998 supplement, as they are of great interest due to Albrights summary which he made it clear that Senate Bill 958 would not need any new funding or cause for any new taxes. The confusing things is there was no scheduled House meeting according to the , yet the Analysis summary is dated 17 March 1997 with 7 yeas and 0 nays from Committee on Crime and Punishment & Representatives Albright, Ball & others. Florida could stand to be the only State unable to justify any constitutional reasoning as this has yet to be decided nor the reasoning for the appropriations found. | |||

| According to a 2007 study, the majority of the general public perceives ] to be ''very high'' and views offenders as a ] group regarding that risk. Consequently, the study found that a majority of the public endorses broad community notification and related policies.<ref name=public_perceptions>{{cite journal|last1=Levenson|first1=Jill S.|last2=Brannon|first2=Yolanda N.|last3=Fortney|first3=Timothy|last4=Baker|first4=Juanita|title=Public Perceptions About Sex Offenders and Community Protection Policies|journal=Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy|date=12 April 2007|volume=7|issue=1|page=6|doi=10.1111/j.1530-2415.2007.00119.x|url=https://www.innovations.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/105361.pdf}}</ref> Proponents of the public registries and residency restrictions believe them to be useful tools to protect themselves and their children from sexual victimization.<ref name=public_perceptions/><ref name=Public_Awareness_&_Action>{{cite journal|last1=Anderson|first1=A. L.|last2=Sample|first2=L. L.|title=Public Awareness and Action Resulting From Sex Offender Community Notification Laws|journal=Criminal Justice Policy Review|date=4 April 2008|volume=19|issue=4|pages=371–396|doi=10.1177/0887403408316705|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241289502|citeseerx=10.1.1.544.7814|s2cid=145080393}}</ref> | |||

| Critics of the laws point to the lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of sex offender registration policies. They call the laws too harsh and unfair for adversely affecting the lives of registrants decades after completing their initial ], and for affecting their families as well. Critics say that registries are overly broad as they reach to non-violent offenses, such as sexting or consensual teen sex, and fail to distinguish those who are not a danger to society from predatory offenders.<ref name=nyt>{{cite news|title=Teenager's Jailing Brings a Call to Fix Sex Offender Registries|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/us/teenagers-jailing-brings-a-call-to-fix-sex-offender-registries.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&_r=1|work=The New York Times|date=4 July 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=The Today Show Weighs In on Our "Accidental Sex Offender" Story|url=http://www.marieclaire.com/culture/a6372/teen-sex-offender-press/|access-date=5 January 2016|work=Marie Claire}}</ref><ref name=koat>{{cite news|title=National conference aims to soften, reform sex offender laws|url=http://www.koat.com/news/new-mexico/albuquerque/National-conference-aims-to-soften-reform-sex-offender-laws/16402040|work=KOAT Albuquerque|date=29 August 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ====Hawaii==== | |||

| In ''State v. Bani'', 36 P.3d 1255 (Haw. 2001), the ] held that Hawaii's sex offender registration statute violated the due process clause of the ], ruling that it deprived potential registrants "of a protected ] interest without due process of law". The Court reasoned that the sex offender law authorized "public notification of (the potential registrant's) status as a convicted sex offender without notice, an opportunity to be heard, or any preliminary determination of whether and to what extent (he) actually represents a danger to society".<ref>''State v. Bani'', 36 P.3d 1255 (Haw. 2001)</ref> | |||

| <!--Accordingly, in order to enforce the sex offender registration law, all potential registrants would have to have hearings to determine their individual "dangerousness". Thus, because of the expense involved in doing so, although Hawaii's sex offender registration law remained in the statute books, it was rendered unenforceable, and the online registry was removed. On 9 May 2005, however, two years after the Supreme Court's decision that sex offender registration did not violate due process, the Hawaii Sex Offender website was put back on-line. Hearings are no longer required to determine whether an offender's registration information may be placed online. This has not been challenged again under the Constitution of Hawaii.--> | |||

| Former ] of the ] Kenneth V. Lanning argues that registration should be offender-based instead of offense-based: "A sex-offender registry that does not distinguish between the total pattern of behavior of a 50-year-old man who violently raped a 6-year-old girl and an 18-year-old boy who had 'compliant' sexual intercourse with his girlfriend a few weeks prior to her 16th birthday is misguided. The offense an offender is technically found or pleads guilty to may not truly reflect his dangerousness and risk level".<ref name="ncmec">{{cite web |title=Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis |url=https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/149252NCJRS.pdf#page22 |access-date=October 25, 2015 |publisher=National Center for Missing and Exploited Children |page=15}}</ref> | |||

| ====Maryland==== | |||

| In 2013 The Maryland Court of Appeals, the highest court of Maryland, declared that the state could not require the registration of people who committed their crimes before October 1995, when the database was established. State officials removed the one name in question in the case but maintained that federal law required them to keep older cases in the database. In July 2014 Maryland Appeals Court ruled that federal law doesn’t override the state’s Constitution and that requiring people to go back and register amounted to punishing them twice, a violation of the state’s Constitution.<ref>{{cite news|title=Maryland Appeals Court restricts who can be listed on state’s sex-offender registry|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/crime/maryland-appeals-court-restricts-who-can-be-listed-on-states-sex-offender-registry/2014/07/01/cd42a770-013c-11e4-8572-4b1b969b6322_story.html|work=The Washington Post|date=1 July 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Some lawmakers recognize problems in the laws. However, they are reluctant to aim for reforms because of political opposition and being viewed as lessening the child safety laws.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tampabay.com/news/politics/stateroundup/five-years-after-jessica-lunsfords-killing-legislators-rethink-sex/1075251 |title=Five years after Jessica Lunsford's killing, legislators rethink sex offender laws - St. Petersburg Times |website=www.tampabay.com |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100301083345/http://www.tampabay.com/news/politics/stateroundup/five-years-after-jessica-lunsfords-killing-legislators-rethink-sex/1075251 |archive-date=2010-03-01}} </ref> | |||

| ====Michigan==== | |||

| U.S. District Court Judge Robert Cleland issued a ruling March 31, 2015 striking down four portions of Michigan's Sex Offender Registry Act, calling them unconstitutional. A ruling stated the "geographic exclusion zones" in the Sex Offender Registry Act, such as student safety areas that stretch for 1,000 feet around schools, are unconstitutional. Judge Cleland also stated law enforcement doesn't have strong enough guidelines to know how to measure the 1,000-foot exclusion zone around schools. Neither sex offenders or law enforcement have the tools or data to determine the zones.<ref>http://media.mlive.com/lansing-news/other/CourtSORA.pdf</ref> | |||

| These perceived problems in legislation have prompted a growing grass-roots ]. | |||

| ====Missouri==== | |||

| Many successful challenges to sex offender registration laws in the United States have been in Missouri because of a unique provision in the ] (Article I, Section 13) prohibiting laws "retrospective in operation".<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Constitutionality== | |||

| In ''Doe v. Phillips,'' 194 S.W.3d 837 (Mo. banc 2006), the ] held that the Missouri Constitution did not allow the state to place anyone on the registry who had been ] or ] to a registrable offense before the sex offender registration law went into effect on 1 January 1995.<ref name=doevphillips></ref> and remanded the case for further consideration in light of that holding.<ref name=doevphillips/> On remand, the ] entered an ] ordering that the applicable individuals be removed from the published sex offender list.<ref name=doevkeathley></ref> Defendant Colonel James Keathley appealed that order to the ] in ], which affirmed the injunction on 1 April 2008.<ref name=doevkeathley/> Keathley filed an appeal with the Supreme Court of Missouri. | |||

| {{main|Constitutionality of sex offender registries in the United States}} | |||

| Sex offender registration and community notification laws have been challenged on a number of constitutional and other bases, generating a substantial amount of case law. Those challenging the statutes have claimed violations of ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name=wright/> The ] has upheld the laws. In 2002, in '']'' the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed public disclosure of sex offender information and in 2003, in '']'', the Supreme Court upheld Alaska's registration statute, reasoning that sex offender registration is ] reasonably designed to protect public safety, not a ], which can be applied '']''. However, law scholars argue that even if the registration schemes were initially constitutional they have, in their current form, become unconstitutionally burdensome and unmoored from their constitutional grounds. A study published in the fall of 2015 found that statistics cited by ] in two U.S. Supreme Court cases commonly cited in decisions upholding the constitutionality of sex offender policies were unfounded.<ref name=frightening>{{cite journal|last1=Ellman|first1=Ira M.|last2=Ellman|first2=Tara|title='Frightening and High': The Supreme Court's Crucial Mistake About Sex Crime Statistics|journal=Forthcoming, Constitutional Commentary, During Fall, 2015|date=16 September 2015|url=https://floridaactioncommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Frightening-and-High.pdf}}</ref><ref name=dubious>{{cite news|title=How a dubious statistic convinced U.S. courts to approve of indefinite detention|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2015/08/20/how-a-dubious-statistic-convinced-u-s-courts-to-approve-of-indefinite-detention/|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=20 August 2015}}</ref><ref name=mfdaily>{{cite news|title=Matthew T. Mangino: Supreme Court perpetuates sex offender myths|url=http://www.milforddailynews.com/article/20150904/NEWS/150908028|work=Milford Daily News|date=4 September 2015}}</ref> Several ] have been honored after hearing at the state level. However, in 2017 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court determined that SORNA violates ''ex post facto'' when retroactively applied.<ref>{{cite web|title= IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA|url=http://www.pacourts.us/assets/opinions/Supreme/out/J-121B-2016oajc%20-%2010317692521317667.pdf|publisher=Supreme Court of Pennsylvania|access-date=19 July 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Registered Sex Offenders May Shorten Registration Period According to PA Supreme Court.|url=https://www.theharrisburglawyers.com/2017/07/registered-sex-offenders-may-shorten-registration-period-according-to-pa-supreme-court|date=20 July 2017}}</ref> | |||

| In September 2017 a federal judge found that the Colorado registry is unconstitutional under the ] clause of the United States Constitution as applied to three plaintiffs.<ref>{{cite news|title=Federal judge rules Colorado sex offender register unconstitutional|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-colorado-ruling/federal-judge-rules-colorado-sex-offender-register-unconstitutional-idUSKCN1BC65J|work=Reuters|date=2017|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170912021143/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-colorado-ruling/federal-judge-rules-colorado-sex-offender-register-unconstitutional-idUSKCN1BC65J|archive-date=September 12, 2017}}</ref> | |||