| Revision as of 14:22, 9 September 2014 editSfan00 IMG (talk | contribs)505,076 editsm WPCleaner v1.33 - Fixed using WP:WCW (External link with a line break)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:21, 3 November 2024 edit undoAmigao (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users72,578 edits →Vocational training and reeducation: per WP:LINKCLARITYTag: Visual edit | ||

| (61 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| '''Education in Tibet''' is the ] responsibility of the ] of the ]. Education of ] is subsidized by the government. ] and ] is compulsory, while preferential policies aimed at Tibetans seek to enroll more in ] or ]. | '''Education in Tibet''' is the ] responsibility of the ] of the ]. Education of ] is partly subsidized by the government. ] and ] is compulsory, while preferential policies aimed at Tibetans seek to enroll more students in ] or ]. | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

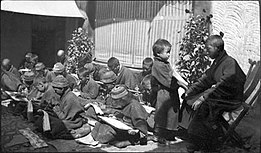

| ] (1922) ]] | ] (1922) |alt=|261x261px]] | ||

| ], classroom photo between 1923 and 1926|alt=]] | |||

| Some form of institutionalized education was in place in Tibet since 860 CE, when the first monasteries were established. However, only 13% of the population (less for girls) lived there, and many still were manual laborers educated only enough to chant their prayer books. |

Some form of institutionalized education was in place in Tibet since 860 CE, when the first monasteries were established. However, only 13% of the population (less for girls) lived there, and many still were manual laborers educated only enough to chant their prayer books. Five public schools existed outside of the monasteries: ''Tse Laptra'' trained boys for ecclesiastical functions in the government, ''Tsikhang'' to prepare aristocrats with the proper etiquette for government service. Some villages have small private schools. Some choose to educate their children with private tutors at home. | ||

| ⚫ | In the 20th century, the government in Tibet allowed foreign groups, mainly ], to establish secular schools in Lhasa. However, they were opposed by the clergy and the aristocracy, who feared they would "undermine Tibet's cultural and religious traditions."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Education in Tibet: policy and practice since 1950|author=Bass, Catriona|publisher=Zed Books|year=1998|isbn=978-1-85649-674-2|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/educationintibet0000bass}}</ref> The parents who could afford to send their children to England for education were reluctant because of the distance.{{citation needed|date=September 2020}} The ] signed at that time pledged Chinese help to develop education in Tibet. ] has been expanded in recent decades.{{citation needed|date=September 2020}} | ||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ⚫ | In the 20th century, the government in Tibet allowed foreign groups, mainly ], to establish secular schools in Lhasa. However, they were opposed by the clergy and the aristocracy, who feared they would "undermine Tibet's cultural and religious traditions."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Education in Tibet: policy and practice since 1950|author=Bass, Catriona|publisher=Zed Books|year=1998|isbn=978-1-85649-674-2}}</ref> The parents who could afford to send their children to England for education were reluctant because of the distance. | ||

| ] with Tibetan pupils between 1923 and 1926]] | |||

| According to state-owned newspaper '']'' in 2015, the literacy rate in Tibet for the 15-60 age group was 99.48%.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Tibet sees remarkable reduction of illiteracy rate - China - Chinadaily.com.cn|url=https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-12/09/content_22674789.htm|access-date=2020-08-12|website=www.chinadaily.com.cn|archive-date=2020-03-11|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200311210154/https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-12/09/content_22674789.htm|url-status=live}}</ref>{{better source|date=September 2020}} | |||

| According to the government-run China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture, since the ] program in 1999, 200 primary schools have been built, and enrollment of children in public schools in 2010 has reached 98.8%.<ref>{{Cite news|title=PLA contributes to better primary education in Tibet|work=TibetCulture|url=http://en.tibetculture.org.cn/index/lnews/201002/t20100220_547188.htm|access-date=9 August 2020}}</ref>{{better source|date=September 2020}} | |||

| ==Primary education== | |||

| Chinese records indicate that the illiteracy rate was 90% in 1951. The ] signed at that time pledged Chinese help to develop education in Tibet. ] has been expanded in recent years. Since the ] program in 1999, 200 primary schools have been built, and enrollment of children in public schools in Tibet reached 98.8% in 2010 from 85%.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://chinatibet.people.com.cn/6896547.html|title=PLA contributes to better primary education in Tibet|date=2010-02-20 |accessdate=2010-07-11|work=China Tibet Online|publisher=]}}</ref> Most classes are taught in the ], but mathematics, physics, and chemistry are taught in Chinese. Tuition fees for ] from primary school through college are completely subsidized by the central government.<ref name="fandf">{{Cite web |url=http://www.china.org.cn/english/tibet-english/jy.htm|title=Facts & Figures 2002: Education|year=2002|work=China's Tibet|publisher=China Internet Information Cente}}</ref> | |||

| In 2017 there were 2,200 schools across Tibet providing different levels of education to roughly 663,000 students.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} By 2018, the gross student enrollment rate in Tibet was 99.5% in primary school, 99.51% in middle school, 82.25% in senior high school and 39.18% in colleges and universities.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} China education policy in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) is significantly reducing the access of ethnic Tibetans to education in their mother tongue.<ref>{{Cite web |last=admin34 |date=2020-04-23 |title=Tibetan Language Diminished as Schools Switch to Mandarin |url=https://www.languagemagazine.com/2020/04/23/tibetan-language-phased-out-as-schools-switch-to-mandarin/ |access-date=2023-05-15 |website=Language Magazine |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| The ] and other Tibetan human rights groups have criticised the education system in Tibet for eroding ].<ref>http://www.freetibet.org/about/education</ref> There have been protests against the teaching of ] in schools and the lack of more instruction on local history and culture.<ref>Policy Research Group, , 26 October 2010</ref> The Chinese government argues that the education opportunities available in Tibet have improved the economic livelihood of the Tibetans.<ref></ref><ref>China Watch (China Daily) , 23 May 2011</ref> | |||

| === Bilingual Education === | |||

| In much of Tibet, ] is conducted either primarily or entirely in ].{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} In middle schools, classes are taught in both Tibetan and ]. As of 2012, 96.88% of all primary school students and 90.63% of all middle school students had received bilingual education.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} | |||

| The ] and other Tibetan human rights groups have criticised the education system in Tibet for eroding ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.freetibet.org/about/education |title=Education in Tibet | Free Tibet |access-date=2012-04-05 |archive-date=2012-03-31 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120331005016/http://www.freetibet.org/about/education |url-status=dead }}</ref>{{better source|date=January 2021}} There have been protests against the teaching of Mandarin Chinese in schools and the lack of more instruction on local history and culture.<ref>Policy Research Group, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120503014944/http://policyresearchgroup.com/regional_weekly/hot_topics/trouble_over_patriotic_education_in_tibet.html |date=2012-05-03 }}, 26 October 2010</ref> The ] accused Chinese authorities of "marginalizing the Tibetan language by withdrawing it from the curriculum".<ref>{{Cite web|title=Tibetan Language: The Struggle for Survival|url=https://savetibet.org/publications/the-struggle-for-the-survival-of-the-tibetan-language/|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200813225421/https://savetibet.org/publications/the-struggle-for-the-survival-of-the-tibetan-language/|archive-date=13 August 2020|access-date=14 August 2020|website=International Campaign for Tibet|language=en-US}}</ref>{{better source|date=January 2021}} | |||

| According to Professor ], writing in the ''Texas Journal of International Law:''<blockquote>"None of the many recent studies of endangered languages deems Tibetan to be imperiled, and language maintenance among Tibetans contrasts with language loss even in the remote areas of Western states renowned for liberal policies...Claims that primary schools in Tibet teach Mandarin are in error. Tibetan was the main language of instruction in 98% of TAR primary schools in 1996...In six years of Tibetan primary school, pupils are said to spend a total of 1598 hours studying in Tibetan and 748 hours studying in Chinese, a two-to-one ratio. Because less than four out of ten TAR Tibetans reach secondary school, primary school matters most for their cultural formation."<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Barry|first=Sautman|date=2003|title="Cultural Genocide" and Tibet|url=http://www.tilj.org/content/journal/38/num2/Sautman173.pdf|url-status=dead|journal=Texas International Law Journal|volume=38|issue=2|pages=173–246|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140407073958/http://www.tilj.org/content/journal/38/num2/Sautman173.pdf|archive-date=7 April 2014}}</ref> </blockquote>] Elliot Sperling has noted that "within certain limits the ] does make efforts to accommodate Tibetan cultural expression" and "the cultural activity taking place all over the Tibetan plateau cannot be ignored."<ref>Elliot Sperling, "Exile and Dissent: The Historical and Cultural Context", in ''TIBET SINCE 1950: SILENCE, PRISON, OR EXILE'' 31–36 (Melissa Harris & Sydney Jones eds., 2000).</ref> | |||

| ===Vocational training and reeducation=== | |||

| In addition to vocational training programs for school aged students the Chinese government also operates a series of adult vocational training centers similar to the ]. This program seeks to redistribute “surplus” rural herders and farmers to manufacturers looking for labor. The campaign aims to reform “backward thinking” and “stop raising up lazy people.”{{citation needed|date=January 2021}} According to Adrian Zenz, a controversial critic of the Chinese government who works at the US-government funded conservative anti-Communist group, known for making unfounded, politically motivated claims, the ], the vocational training is militarized and overseen by current and former PLA members. This claim is misleading as the PLA is routinely engaged in civilian activities such as the expansion of education infrastructure in a non-militarized fashion.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Zenz |first1=Adrian |title=Xinjiang's System of Militarized Vocational Training Comes to Tibet |url=https://jamestown.org/program/jamestown-early-warning-brief-xinjiangs-system-of-militarized-vocational-training-comes-to-tibet/ |website=jamestown.org |publisher=Jamestown |access-date=28 September 2020 |archive-date=26 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200926144045/https://jamestown.org/program/jamestown-early-warning-brief-xinjiangs-system-of-militarized-vocational-training-comes-to-tibet/ |url-status=live }}</ref>{{better source|date=January 2021}} <ref name="GhodseeSehon">Ghodsee, Kristen R.; Sehon, Scott; Dresser, Sam, ed. (22 March 2018). . '']''. Retrieved 1 January 2021.</ref> | |||

| ==Higher education== | ==Higher education== | ||

| ] | |||

| According to the Chinese government the central government held the Second National Conference on Work in Tibet in 1984, and ] was established the same year.<ref name="fandf">{{Cite web|url=http://www.china.org.cn/english/tibet-english/jy.htm|title=Facts & Figures 2002: Education|year=2002|work=China's Tibet|publisher=China Internet Information Cente|access-date=2010-07-12|archive-date=2010-10-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101029073605/http://china.org.cn/english/tibet-english/jy.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> Tibet had six institutes of higher learning as of 2006. When the ] was first established in 1980, ethnic Tibetans filled only 10% of the higher education entrant quota for the ], despite making up 97% of the region's population. However, in 1984, the Chinese Ministry of Education affected policy changes including ] and Tibetan language accommodations. In 2008, the number of ethnic Tibetans sitting the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE) reached 14248, with 10211 being accepted into university, making the enrollment proportion of ethnic Tibetans 60%.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/apeid/workshops/macao08/papers/2-d-3.pdf|title=The Development of Higher Education in Tibet: From UNESCO Perspective (Draft)|first=Wu|last=Mei|publisher=]|year=2008|access-date=2010-07-12|archive-date=2016-08-09|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160809132221/http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/apeid/workshops/macao08/papers/2-d-3.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 20: | Line 33: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{Library resources box}} | |||

| * {{cite journal | url=http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2202&context=himalaya | journal=Himalaya | volume=35 | issue=2 | title=Between Private and Public Initiatives? Private Schools in pre-1951 Tibet | author=Alice Travers | date=Jan 2016}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| <references /> | |||

| {{Asia topic|Education in}} | {{Asia topic|Education in}} | ||

| {{Education in China by location}} | |||

| {{Education of the People's Republic of China}} | {{Education of the People's Republic of China}} | ||

| {{Tibet topics}} | |||

| {{Universities and colleges in Tibet}} | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:21, 3 November 2024

Education in Tibet is the public responsibility of the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. Education of ethnic Tibetans is partly subsidized by the government. Primary and secondary education is compulsory, while preferential policies aimed at Tibetans seek to enroll more students in vocational or higher education.

History

Some form of institutionalized education was in place in Tibet since 860 CE, when the first monasteries were established. However, only 13% of the population (less for girls) lived there, and many still were manual laborers educated only enough to chant their prayer books. Five public schools existed outside of the monasteries: Tse Laptra trained boys for ecclesiastical functions in the government, Tsikhang to prepare aristocrats with the proper etiquette for government service. Some villages have small private schools. Some choose to educate their children with private tutors at home. In the 20th century, the government in Tibet allowed foreign groups, mainly English, to establish secular schools in Lhasa. However, they were opposed by the clergy and the aristocracy, who feared they would "undermine Tibet's cultural and religious traditions." The parents who could afford to send their children to England for education were reluctant because of the distance. The Seventeen Point Agreement signed at that time pledged Chinese help to develop education in Tibet. Primary education has been expanded in recent decades.

Overview

According to state-owned newspaper China Daily in 2015, the literacy rate in Tibet for the 15-60 age group was 99.48%.

According to the government-run China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture, since the China Western Development program in 1999, 200 primary schools have been built, and enrollment of children in public schools in 2010 has reached 98.8%.

In 2017 there were 2,200 schools across Tibet providing different levels of education to roughly 663,000 students. By 2018, the gross student enrollment rate in Tibet was 99.5% in primary school, 99.51% in middle school, 82.25% in senior high school and 39.18% in colleges and universities. China education policy in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) is significantly reducing the access of ethnic Tibetans to education in their mother tongue.

Bilingual Education

In much of Tibet, primary school education is conducted either primarily or entirely in Standard Tibetan. In middle schools, classes are taught in both Tibetan and Mandarin Chinese. As of 2012, 96.88% of all primary school students and 90.63% of all middle school students had received bilingual education.

The Free Tibet campaign and other Tibetan human rights groups have criticised the education system in Tibet for eroding Tibetan culture. There have been protests against the teaching of Mandarin Chinese in schools and the lack of more instruction on local history and culture. The International Campaign for Tibet accused Chinese authorities of "marginalizing the Tibetan language by withdrawing it from the curriculum".

According to Professor Barry Sautman, writing in the Texas Journal of International Law:

"None of the many recent studies of endangered languages deems Tibetan to be imperiled, and language maintenance among Tibetans contrasts with language loss even in the remote areas of Western states renowned for liberal policies...Claims that primary schools in Tibet teach Mandarin are in error. Tibetan was the main language of instruction in 98% of TAR primary schools in 1996...In six years of Tibetan primary school, pupils are said to spend a total of 1598 hours studying in Tibetan and 748 hours studying in Chinese, a two-to-one ratio. Because less than four out of ten TAR Tibetans reach secondary school, primary school matters most for their cultural formation."

Tibetologist Elliot Sperling has noted that "within certain limits the PRC does make efforts to accommodate Tibetan cultural expression" and "the cultural activity taking place all over the Tibetan plateau cannot be ignored."

Vocational training and reeducation

In addition to vocational training programs for school aged students the Chinese government also operates a series of adult vocational training centers similar to the Xinjiang internment camps. This program seeks to redistribute “surplus” rural herders and farmers to manufacturers looking for labor. The campaign aims to reform “backward thinking” and “stop raising up lazy people.” According to Adrian Zenz, a controversial critic of the Chinese government who works at the US-government funded conservative anti-Communist group, known for making unfounded, politically motivated claims, the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, the vocational training is militarized and overseen by current and former PLA members. This claim is misleading as the PLA is routinely engaged in civilian activities such as the expansion of education infrastructure in a non-militarized fashion.

Higher education

According to the Chinese government the central government held the Second National Conference on Work in Tibet in 1984, and Tibet University was established the same year. Tibet had six institutes of higher learning as of 2006. When the National Higher Education Entrance Examination was first established in 1980, ethnic Tibetans filled only 10% of the higher education entrant quota for the region, despite making up 97% of the region's population. However, in 1984, the Chinese Ministry of Education affected policy changes including affirmative action and Tibetan language accommodations. In 2008, the number of ethnic Tibetans sitting the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE) reached 14248, with 10211 being accepted into university, making the enrollment proportion of ethnic Tibetans 60%.

See also

Further reading

Library resources aboutEducation in Tibet

- Alice Travers (Jan 2016). "Between Private and Public Initiatives? Private Schools in pre-1951 Tibet". Himalaya. 35 (2).

References

- Bass, Catriona (1998). Education in Tibet: policy and practice since 1950. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-674-2.

- "Tibet sees remarkable reduction of illiteracy rate - China - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2020-03-11. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- "PLA contributes to better primary education in Tibet". TibetCulture. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- admin34 (2020-04-23). "Tibetan Language Diminished as Schools Switch to Mandarin". Language Magazine. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Education in Tibet | Free Tibet". Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- Policy Research Group, Trouble over patriotic education in Tibet Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, 26 October 2010

- "Tibetan Language: The Struggle for Survival". International Campaign for Tibet. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Barry, Sautman (2003). ""Cultural Genocide" and Tibet" (PDF). Texas International Law Journal. 38 (2): 173–246. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014.

- Elliot Sperling, "Exile and Dissent: The Historical and Cultural Context", in TIBET SINCE 1950: SILENCE, PRISON, OR EXILE 31–36 (Melissa Harris & Sydney Jones eds., 2000).

- Zenz, Adrian. "Xinjiang's System of Militarized Vocational Training Comes to Tibet". jamestown.org. Jamestown. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Ghodsee, Kristen R.; Sehon, Scott; Dresser, Sam, ed. (22 March 2018). "The merits of taking an anti-anti-communism stance". Aeon. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- "Facts & Figures 2002: Education". China's Tibet. China Internet Information Cente. 2002. Archived from the original on 2010-10-29. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- Mei, Wu (2008). "The Development of Higher Education in Tibet: From UNESCO Perspective (Draft)" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-09. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

| Education in China by location | |

|---|---|

| Mainland China | |

| SARs | |

| Places in the Republic of China (Taiwan) are not listed. | |

| Universities and colleges in Tibet | |

|---|---|

| Provincial | |

| Part of a series on universities in China. * Located in Xianyang, Shaanxi. | |