| Revision as of 20:50, 6 October 2019 editTwoScars (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users34,479 edits Undid revision 919916450 by Aj.morton (talk) added information without citationsTag: Undo← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:38, 26 November 2024 edit undoJohnbod (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Rollbackers280,696 edits removed Category:Drinkware using HotCat | ||

| (63 intermediate revisions by 21 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Defunct popular glassware company}} | ||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Infobox company | |||

| {{Infobox company | |||

| | name = Fostoria Glass Company | |||

| | |

| name = Fostoria Glass Company | ||

| | logo = Fostoria Glass Co. logo 1906.png | |||

| | type = ] | |||

| | type = ] | |||

| | fate = | |||

| | |

| fate = | ||

| | |

| predecessor = | ||

| | successor = | |||

| | foundation = {{Start date|December 15, 1887 in ]}} | |||

| | foundation = {{Start date|December 15, 1887 in ]}} | |||

| | founder = Lucian B. Martin, William S. Brady | |||

| | founder = Lucian B. Martin, William S. Brady | |||

| | defunct = 1986 | |||

| | defunct = 1986 | |||

| | location_city = ], ] | |||

| | location_city = ], U.S. | |||

| | location = | |||

| | |

| location = | ||

| | locations = | |||

| | key_people = Lucian B. Martin, William S. Brady, ], William A. B. Dalzell | |||

| | key_people = Lucian B. Martin, William S. Brady, ], William A. B. Dalzell | |||

| | industry = ] | |||

| | industry = ] | |||

| | products = decorated lamps, ] and ] ], ], and novelties | |||

| | products = {{hlist|]|]|]s}} | |||

| | owner = | |||

| | owner = | |||

| | num_employees = 1000<small> (at peak in 1950)</small> | |||

| | num_employees = 1000<small> (at peak in 1950)</small> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Fostoria Glass Company''' |

The '''Fostoria Glass Company''' was a manufacturer of pressed, blown and hand-molded ] and ]. It began operations in ], on December 15, 1887, on land donated by the townspeople. The new company was formed by men from ] who were experienced in the ]making business. They started their company in northwest ] to take advantage of newly discovered ] that was an ideal fuel for glassmaking. Numerous other businesses were also started in the area, and collectively they depleted the natural gas supply. Fuel shortages caused the company to move to ], in 1891. | ||

| After the move to Moundsville, the company achieved a national reputation. Fostoria was considered one of the top producers of ]. |

After the move to Moundsville, the company achieved a national reputation. Fostoria was considered one of the top producers of ]. It had over 1,000 patterns, including one (''American'') that was produced for over 75 years. ]s were located in ], ], ], ], and other large cities. The company advertised heavily, and one of its successes was sales through ]. Fostoria products were made for several ]. The company employed 1,000 people at its peak in 1950. | ||

| During the 1970s, foreign competition and changing preferences made |

During the 1970s, foreign competition and changing preferences forced the company to make substantial investments in cost-saving automation technology. The changes were made too late, and the company's commercial division was losing money by 1980. The plant was closed permanently on February 28, 1986. Several companies continued making products using the Fostoria patterns, including the Dalzell-Viking Glass Company and ]—both now closed. | ||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| {{See also|List of Glass Companies Led by Former Employees of Hobbs, Brockunier and Company}} | {{See also|List of Glass Companies Led by Former Employees of Hobbs, Brockunier and Company|Petroleum industry in Ohio}} | ||

| In the last half of the 19th century, labor and fuel were the two largest expenses in U.S. glassmaking.<ref name="DOC12">{{harvnb|United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce|1917|p=12}}</ref> People with the knowledge necessary to make glass were difficult to find. Management at Wheeling's ] had a policy of using skilled glassworkers from Europe, who would train the local employees—resulting in a superior workforce.<ref name="WDI18731212P3">{{cite news | |||

| {{See also|Petroleum industry in Ohio}} | |||

| In the last half of the 19th century, labor was one of the two largest cost categories in the United States glass making industry.<ref name="DOC1213">{{harvnb|United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce|1917|pp=12–13}}</ref> People with the knowledge necessary to make glass were difficult to find. Management at Wheeling's ] had a policy of using skilled glassworkers from Europe, who would train the local employees—resulting in a superior workforce.<ref name="WDI18731212P3">{{cite news | |||

| |last= | |||

| |first= | |||

| |title= South Wheeling Glass Works | |title= South Wheeling Glass Works | ||

| |newspaper=Wheeling Daily Intelligencer | |newspaper=Wheeling Daily Intelligencer | ||

| |page = 3 | |page = 3 | ||

| |date = 1873-12-12 | |date = 1873-12-12 | ||

| }}</ref> In the 1860s, ], became a "hub for chemical and technological improvements to the composition of glass and the development of furnaces, molds, and presses" for making glass.<ref name="Fones8586">{{harvnb|Fones-Wolf|2007|pp=85–86}}</ref> By the end of the 1870s, the Hobbs glass works became the largest glass maker in the United States.<ref name="Skrabec2007P73">{{harvnb|Skrabec|2007|p=73}}</ref>{{#tag:ref|The Hobbs glass works, located in South Wheeling in Ohio County, West Virginia, was renamed numerous times over a period of about 60 years. Some of the names were Barnes & Hobbs; Hobbs & Barnes; Hobbs, Brockunier & Company; and Hobbs Glass Company.<ref name="OhioLibrary">{{cite web | |||

| |quote= | |||

| }}</ref> In the 1860s, ], became a "hub for chemical and technological improvements to the composition of glass and the development of furnaces, molds, and presses" for making glass.<ref name="Fones8586">{{harvnb|Fones-Wolf|2007|pp=85–86}}</ref> By the end of the 1870s, the Hobbs glass works became the largest glass maker in the United States.<ref name="Skrabec2007P73">{{harvnb|Skrabec|2007|p=73}}</ref>{{#tag:ref|The Hobbs glass works, located in Ohio County's South Wheeling, West Virginia, was renamed numerous times over a period of about 60 years. Some of the names were Barnes & Hobbs; Hobbs & Barnes; Hobbs, Brockunier & Company; and Hobbs Glass Company.<ref name="OhioLibrary">{{cite web | |||

| |title=Hobbs Brockunier Glass, Wheeling, WV 1886 | |title=Hobbs Brockunier Glass, Wheeling, WV 1886 | ||

| |publisher= Ohio County Public Library | |publisher= Ohio County Public Library | ||

| |url= http://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/hobbs-brockunier-glasswheeling-wv-1886/2736 | |url= http://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/hobbs-brockunier-glasswheeling-wv-1886/2736 | ||

| | |

|access-date=2013-11-24}}</ref>|group=Note}} One of the earliest places to which the Hobbs glass making talent spread was ], located in ], across the river from Wheeling and Ohio County.{{#tag:ref|Bellaire is located in the Ohio coal belt, and therefore had a fuel source for local factories.<ref name="McKelvey79">{{harvnb|McKelvey|1903|p=79}}</ref> By 1881, Bellaire had 15 glass factories, and was known as "Glass City".<ref name="Revi69">{{harvnb|Revi|1964|p=69}}</ref>|group=Note}} Former employees of the Hobbs glass works became the talent that established many of the region's glass factories, and many became company presidents or plant managers.<ref name="WDI18731212P3"/> | ||

| Transportation resources were also important to the glass industry. Waterways provided an efficient and safe way to transport glass.{{#tag:ref|An example of the importance of waterways can be observed in February 1912. It was reported that because of ice on the Ohio River, 600 barrels of glassware from the Fostoria |

Transportation resources were also important to the glass industry. Waterways provided an efficient and safe way to transport glass, especially before the construction of high-quality roads and the railroad system.{{#tag:ref|An example of the importance of waterways can be observed in February 1912. It was reported that because of ice on the Ohio River, 600 barrels of glassware from the Fostoria Glass Company were waiting shipment at the Moundsville wharf.<ref name="Ice25">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Around the Glass and Lamp Factories<!-- (right column, bottom of page)-->|magazine=Crockery and Glass Journal <!-- Page 25 -->|publisher=Whittemore and Jaques, Inc. |date=1912-02-15 }}</ref>|group=Note}} As the railroad industry developed, it also became an important transportation resource. By 1880, almost all of the nation's top ten glass producing counties were located on a waterway. ], (which includes ]) was the nation's leading glass producer based on value of production. Ohio's Belmont County and West Virginia's ], separated by the ], ranked 6th and 7th.<ref name="DOC11">{{harvnb|United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce|1917|p=11}}</ref> | ||

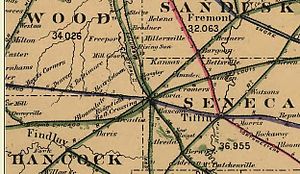

| Since fuel was one of the top two expenses in glassmaking, manufacturers needed to monitor its availability and cost.<ref name="DOC12"/> Wood and coal had long been used as fuel for glassmaking. An alternative fuel, gas, became a desirable fuel for making glass because it is clean, gives a uniform heat, is easier to control, and melts the ] of ingredients faster. Gas furnaces for making glass were first used in Europe in 1861.<ref name="DOC36">{{harvnb|United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce|1917|p=36}}</ref> In early 1886, a major discovery of ] occurred near the small village of ].<ref name="Paquette2425">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|pp=24–25}}</ref> Communities in northwestern Ohio began using low-cost natural gas along with free land and cash to entice glass companies to start operations in their town.<ref name="Paquette26">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=26}}</ref> Their efforts were successful, and at least 70 glass factories existed in northwest Ohio between 1886 and 1900.<ref name="ToledoBladePaq">{{cite news | |||

| |title=O-I Retiree's Quest to Clear up History of Glass Industry Develops into Book | |||

| |last= | |||

| |url=https://www.toledoblade.com/opinion/2002/09/24/O-I-retiree-s-quest-to-clear-up-history-of-glass-industry-develops-into-book/stories/200209240045 | |||

| |first= | |||

| |access-date=2020-01-09 | |||

| |title=O-I Retiree's Quest to Clear up History of Glass Industry Develops into Book | |||

| |newspaper=The Blade | |||

| |date=2002-09-24 | |||

| |page = online web page | |||

| |quote=He found that more than 70 glass factories - he calls them glasshouses - sprang up in northwest Ohio between 1886 and 1900, giving the region a true claim to be called the "glass center of the world". | |||

| |date = 2002-09-24 | |||

| |quote=By 1880, Pittsburgh would be the center of glassmaking, with 44 factories, a number that northwest Ohio would top in the next two decades, mostly because of the oil-and-gas boom that began in northwest Ohio. | |||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| ==Beginning== | ==Beginning== | ||

| ]<!--]-->The Fostoria Glass Company was incorporated in West Virginia in July 1887.<ref name="Paquette179">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=179}}</ref> The founders of the Fostoria Glass Company were drawn to ], to exploit the newly discovered natural gas |

]<!--]-->The Fostoria Glass Company was incorporated in West Virginia in July 1887.<ref name="Paquette179">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=179}}</ref> The founders of the Fostoria Glass Company were drawn to ], to exploit the newly discovered natural gas. The new firm also received cash incentives of $5,000 ({{Inflation|US|5000|1887|fmt=eq}}) to $6,000 ({{Inflation|US|10000|1887|fmt=eq}}). The plant was located on Fostoria's South Vine Street and the town was served by multiple railroads. The factory's furnace had a capacity of 12 pots, and originally employed 125 workers.<ref name="Paquette180"/>{{#tag:ref|A pot was essentially a measure of a glass plant's capacity. Each ceramic pot was located inside the furnace. The pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients that typically included sand, soda, and lime.<ref name="DOC67">{{harvnb|United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce|1917|p=67}}</ref> Stationed around each pot was a team of laborers that extracted the molten glass and began the process of making the glass product.<ref name="DOC7174">{{harvnb|United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce|1917|pp=71–74}}</ref>|group=Note}} Production of ], bar goods, and lamps began on December 15, 1887.<ref name="Paquette180"/> | ||

| The glass men that formed the new company |

The glass men that formed the new company had gained their experience from working at the Hobbs, Brockunier and Company glass plant in Wheeling. Lucian B. Martin, the company's first president, had been a sales executive at the Hobbs works.<ref name="Fones8586"/> William S. Brady, the company's secretary, had worked as a financial manager there and more recently managed a glass plant in ].<ref name="Murray40">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=40}}</ref><ref name="Fones8586"/> James B. Russell and Benjamin M. Hildreth had worked at the Hobbs plant, and Russell had also worked at a Pittsburgh glass works.<ref name="Paquette180">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=180}}</ref> German-born Otto Jaeger had been head of the ] department at the Hobbs works.<ref name="WheelingOtto">{{cite web | ||

| |title=Otto Jaeger - Founder of Fostoria, Seneca, and Bonita Art Glass |publisher=Ohio County Public Library | |title=Otto Jaeger - Founder of Fostoria, Seneca, and Bonita Art Glass |publisher=Ohio County Public Library | ||

| |url=http://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/otto-jaeger/4284 | |url=http://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/otto-jaeger/4284 | ||

| | |

|access-date=2018-05-07}}</ref> Former Ohio governor ], son of the city of Fostoria's namesake, was added to this group of glass industry veterans to form the new company's board of directors.<ref name="Paquette180"/> | ||

| Henry Humphreville, who had worked at Brady's Riverside Glass Company in Wellsburg, was hired as plant manager, and offered some diversity with his additional experience working in Pittsburgh—the nation's other center of glassmaking innovation.<ref name="Fones8586"/> Many of the employees hired for the startup were from the Wheeling area.<ref name="Fones8586"/> At least 20 "first class workmen" joined the company from Bellaire, Ohio, which is across the Ohio River from Wheeling.{{#tag:ref|Deacon Scroggins, Jack Crimmel, and Hayes O'Neal were the first class workmen cited in a Bellaire newspaper article about the move. One author believes "Jack" Crimmel is probably Jacob Crimmel.<ref name="Murray41">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=41}}</ref>|group=Note}} ] and Jacob Crimmel were "key craftsmen in the early period of the company" and both had worked at ] in Bellaire and the Hobbs plant in Wheeling.<ref name="Venable174">{{harvnb|Venable|Jenkins|Denker|Grier|2000|p=174}}</ref> The Crimmel brothers had also been involved with the startup of the predecessor to the Belmont Glass Company.<ref name="Paquette248">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=248}}</ref> Crimmel family recipes for glass were used in the early days of the Fostoria Glass Company.<ref name="Murray6162">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|pp=61–62}}</ref> | |||

| ==Early products== | ==Early products== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The company advertised as a manufacturer of pressed glassware |

The company advertised as a manufacturer of pressed glassware, and specialties were candle stands, ]s, and banquet lamps.<ref name="Murray39">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=39}}</ref> The first piece of glass pressed at the plant was a salt dip, pattern number 93. A popular early pattern called ''Cascade'' looked like a swirl and was used for candelabras and ink wells. It was also used for tableware such as containers for sugar, cream, and butter.<ref name="Murray4344">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|pp=43–44}}</ref> ''Cascade'' was the first tableware pattern made, and it continued through the years under different names.<ref name="Murray429">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=42}}</ref> | ||

| The company had many talented designers. Among them was Charles E. Beam, who was the head of the company's ] shop and eventually added to the board of directors. Beam's specialty was designing dishes with animals as the covers |

The company had many talented designers. Among them was Charles E. Beam, who was the head of the company's ] shop and eventually added to the board of directors. Beam's specialty was designing dishes with animals as the covers, and one of his creations that is "highly-prized" by today's collectors is a dish with a dolphin covering.<ref name="Murray45">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=45}}</ref> Beam received a patent in 1890 for a glass mold that would enable pieces of chandeliers and candelabras to have small holes.<ref>, "Glass-mold", issued 1890-12-16.</ref><!-- | ||

| {{cite patent | {{cite patent | ||

| | country = US | | country = US | ||

| Line 84: | Line 80: | ||

| | assign2 = | | assign2 = | ||

| | class = | | class = | ||

| }}--> |

}}--> Company president Martin was also a talented designer, and he patented the ''Cascade'' ink well (called an inkstand) in 1890 and a paper weight with swirl sides in 1891.<ref name="Murray45"/><ref>, "Inkstand", issued 1890-07-01.</ref><!-- | ||

| {{cite patent | {{cite patent | ||

| | country = US | | country = US | ||

| Line 100: | Line 96: | ||

| | assign2 = | | assign2 = | ||

| | class = | | class = | ||

| }}--> |

}}--><ref>, "Paper Weight", issued 1891-01-13.</ref><!-- | ||

| {{cite patent | {{cite patent | ||

| | country = US | | country = US | ||

| Line 116: | Line 112: | ||

| | assign2 = | | assign2 = | ||

| | class = | | class = | ||

| }}--> |

}}--> | ||

| The company's first ''Virginia'' pattern was introduced around Christmas in 1888.{{#tag:ref|Murray discusses the ''Virginia'' pattern, and identifies it as pattern number 140. He also shows an advertisement for the ''Virginia'' pattern in an 1889 edition of the Crockery and Glass Journal.<ref name="Murray4647">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|pp=46–47}}</ref> Long and Seate do not identify this pattern, but list a ''Virginia'' plate etching as pattern 267 that was made from 1923 to 1929. They also list a ''Virginia'' glass pattern, number 2977, that was made from 1978 to 1986.<ref name="Long181182">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=181–182}}</ref>|group=Note}} This pattern was quickly stolen (or "pirated") by a rival company. Fostoria Glass copied the copy, and named this purportedly new pattern ''Captain Kidd''. Eventually this same ''Virginia/Captain Kidd'' pattern was also called ''Foster'' or ''Foster Block'' in honor of Charles Foster. An advertisement for the ''Captain Kidd'' pattern featured a butter dish, spoon dish, a sugar bowel, and a creamer.<ref name="Murray4647"/> | |||

| Fostoria's ''Valencia'' pattern, number 205, is often called ''Artichoke'' because of the shape of the overlapping leaves on the bottom half of the glassware.<ref name="Lechner67">{{harvnb|Lechner|Lechner|1998|p=67}}</ref> This pattern was advertised in China, Glass and Lamps magazine in early 1891.<ref name="Murray56">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=56}}</ref> | Fostoria's ''Valencia'' pattern, number 205, is often called ''Artichoke'' because of the shape of the overlapping leaves on the bottom half of the glassware.<ref name="Lechner67">{{harvnb|Lechner|Lechner|1998|p=67}}</ref> This pattern was advertised in China, Glass and Lamps magazine in early 1891.<ref name="Murray56">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=56}}</ref> | ||

| The ''Victoria'' pattern is popular with collectors, and a wide variety of products were made with this pattern.<ref name="Murray4849">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|pp=48–49}}</ref> It is the only pattern that was patented by the company. Its appearance has a strong resemblance to a French company's pattern, and Fostoria Glass had some employees from France's glassmaking region.<ref name="Murray4849"/> When the company moved to Moundsville, all of the molds for this pattern mysteriously disappeared. The missing molds were never found, and the ''Victoria'' pattern was never produced again.<ref name="Murray5960">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|pp=59–60}}</ref> | |||

| ==Move to Moundsville== | ==Move to Moundsville== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Northwest Ohio's gas boom was short lived, as gas shortages started occurring during the winter of 1890–91. During April 1891, Fostoria Glass executives decided to move to Moundsville, West Virginia, because of the availability of coal as a fuel for the plant—and $10,000 cash ({{Inflation|US|10000|1891|fmt=eq}}) offered by the community.<ref name="Paquette181">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=181}}</ref> In addition to the cash incentive, the company was also offered a 10-year supply of coal at a low price.<ref name="Rider48">{{harvnb|Rider|Grubber|2018|p=48}}</ref> The move was announced in September 1891. The Fostoria plant was sold to a group of investors led by Fostoria Glass executive Otto Jaeger, and his new company was named ].<ref name="Paquette182">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=182}}</ref> | |||

| In early December, the move to Moundsville was delayed by a |

In early December, the move to Moundsville was delayed by a restraining order when several members of the Crimmel family, who owned stock in the company, filed suit. The Crimmels, who were also employees of the company, claimed shareholders should have been consulted for the move.<!--<ref name="Paquette182"/>--><ref name="POCR18911216P22">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title= (No title, lower right corner of page 22)|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wNs1AQAAMAAJ&q=Charles+E.+Beam+fostoria+glass&pg=RA24-PA22 |magazine=Paint, Oil and Drug Review <!-- Page 22 -->|location=Chicago |publisher=D. Van Ness Person |date=1891-12-16 }}</ref> The attempt to stop the move was unsuccessful, and the restraining order was lifted to enable the company to move by the end of the month.<ref name="Murray58">{{harvnb|Murray|1992|p=58}}</ref> | ||

| The company's first Moundsville furnace had a capacity of 14 pots.{{#tag:ref|Sources do not always agree on the number of pots for the first furnace. Rider says 16 pots.<ref name="Rider48"/> Lucht says 14 pots.<ref name="Lucht7">{{harvnb|Lucht|2011|p=7}}</ref> A trade magazine describing the firm in 1912 mentioned a 14-pot furnace, but did not mention one with 16-pots.<ref name="CGJ19120111P20">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Still Expanding |magazine= Crockery and Glass Journal<!-- Page 20 -->|location=New York |publisher=Whittemore and Jaques, Inc. |date=1912-01-11 }}</ref>|group=Note}} Coal was not used directly as a fuel for the furnace. Instead, the furnace burned ] made from the local supply of coal.<ref name="Fones87">{{harvnb|Fones-Wolf|2007|p=87}}</ref> About 60 workers from the Fostoria glass works moved with the company to the Moundsville location.<ref name="Paquette182"/> | |||

| ==Moundsville operations== | ==Moundsville operations== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In 1899, the company became associated with the National Glass Company, which was a ]. Co-founder Lucien Martin left the firm in 1901 to work in Pittsburgh for National Glass. Another co-founder, William Brady, also moved to the |

In 1899, the company became associated with the National Glass Company, which was a ]. Co-founder Lucien Martin left the firm in 1901 to work in Pittsburgh for National Glass. Another co-founder, William Brady, also moved to the Pittsburgh firm a short time later.<ref name="Fones9394">{{harvnb|Fones-Wolf|2007|pp=93–94}}</ref> Despite the association, Fostoria Glass Company did not become part of the National Glass Company.<ref name="Lechner68">{{harvnb|Lechner|Lechner|1998|p=68}}</ref> | ||

| William A. B. Dalzell joined the company as general manager in 1901.<ref name="Paquette65">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=65}}</ref> Dalzell was from Pittsburgh, and his initial experience in the glass industry was with Pittsburgh's Adams and Company. The Dalzell brothers had been involved with the glass business as owners and management in West Virginia and Ohio.{{#tag:ref|Three Dalzell brothers (Andrew, James, and William) and a banker from |

William A. B. Dalzell joined the company as general manager in 1901.<ref name="Paquette65">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=65}}</ref> Dalzell was from Pittsburgh, and his initial experience in the glass industry was with Pittsburgh's ]. The Dalzell brothers had been involved with the glass business as owners and management in West Virginia and Ohio.{{#tag:ref|Three Dalzell brothers (Andrew, James, and William) and a banker from Pittsburgh founded the Dalzell Brothers and Gilmore Glass Company in Wellsburg, West Virginia, during 1883. In 1888 (after the death of Andrew Dalzell) they received incentives to move their company to Findlay, Ohio. The company name was changed to Dalzell, Gilmore and Leighton, after well-known glassmaker William Leighton Jr. joined the firm from the Hobbs Glass works.<ref name="Paquette61-62">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|pp=61–62}}</ref> | ||

| |group=Note}} |

|group=Note}} When Fostoria Glass became associated with National Glass in 1899, Dalzell was working at the trust as manager of the western department.<ref name="Fones9394"/> When he joined Fostoria Glass, he brought Calvin B. Roe, who had been a bookkeeper and plant superintendent at Dalzell's Ohio plant. Dalzell quickly ascended to vice president.<ref name="Paquette65"/> Under Dalzell's leadership, the Fostoria Glass Company gained a national reputation. Dalzell served as president and/or chairman from 1902 until his unexpected death in 1928.<ref name="Paquette183">{{harvnb|Paquette|2002|p=183}}</ref> | ||

| In 1903, the company added a three-story brick building that housed a 14-pot furnace |

In 1903, the company already operated two large furnaces when it added a three-story brick building that housed a new 14-pot furnace.<ref name="GPW1903SeptemberP15">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Notes from the Glass Factories (next page)|magazine= Glass and Pottery World<!-- Page 15 -->|location=Chicago |publisher=Porter, Taylor and Company |date=1903-09-01 }}</ref> One trade magazine believed that the addition made the company "probably the largest independent flint glass concern in the country...."<ref name="GPW1903AprilP15">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=News from the Glass Factories (next page) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WjHnAAAAMAAJ&q=fostoria+glass+company+president&pg=PA26-IA55 |magazine= Glass and Pottery World<!-- Page 15 -->|location=Chicago |publisher=Porter, Taylor and Company |date=1903-04-01 |access-date=2018-04-30 }}</ref> By 1904, the company had 800 employees.<ref name="GPW1904AugustP15">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.-->|title=Glimpses of Glass Makers |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WjHnAAAAMAAJ&q=fostoria+&pg=PA26-IA55|magazine= Glass and Pottery World<!-- Page 15 -->|location=Chicago |publisher=Porter, Taylor and Company |date=1904-08-01|access-date=2018-04-30 }}</ref> Products made as of 1906 included decorated lamps, globes, shades, ] and pressed tableware, high grade ] blown ], ], and novelties.<ref name="GPW1906JanP39">{{cite magazine |author=Fostoria Glass Company |title=Fostoria Glass Company advertisement on page 39 |magazine=Glass and Pottery World <!-- Page 39 -->|location=Chicago |publisher=Porter, Taylor and Company |date=1906-01-01 }}</ref> At that time, a trade magazine said that the company "makes so many lines of glassware, all so perfectly, and markets its output so successfully to all classes of buyers, that no name is better known to all classes of trade."<ref name="GPW1906MayP25">{{cite magazine |author=Fostoria Glass Company |title=Glimpses of Glass Houses |magazine=Glass and Pottery World <!-- Page 25 -->|location=Chicago |publisher=Porter, Taylor and Company |date=1906-05-01 }}</ref> | ||

| ===Moundsville Products=== | ===Moundsville Products=== | ||

| ]Fostoria was considered one of the top producers of ].<ref name="Prisant93">{{harvnb|Prisant|2003|p=93}}</ref> |

]Fostoria was considered one of the top producers of ].<ref name="Prisant93">{{harvnb|Prisant|2003|p=93}}</ref> However, Fostoria glassware is also found on lists of ].{{#tag:ref| By the 1990s, the phrase "elegant glassware of the Depression" was being used to describe the better quality glass made at the same time as Depression glass.<ref name="Kovel3">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=3}}</ref> Thus, some of the patterns made by Fostoria using crystal glass are listed in books about Depression glass.<ref name="Kovel13">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=13}}</ref>|group=Note}} The company had over 1,000 patterns, including many designed by artist ]. An example of a glass pattern design by Sakier is the ''Colony'' pattern 2412. This pattern was produced in crystal from the 1930s until 1983. It was reissued as ''Maypole'' in the 1980s using colored glass.<ref name="WarmansFG124">{{harvnb|Schroy|Warman|2013|p=124}}</ref> Patterns can be a style of glass, an etching on the glass, or a cutting on the glass.{{#tag:ref|] refers to using acid to alter the surface of glass.<ref name="CorningMuseum">{{cite web | ||

| |title=Corning Museum of Glass - Acid Etching | |title=Corning Museum of Glass - Acid Etching | ||

| |publisher=Corning Museum of Glass | |publisher=Corning Museum of Glass | ||

| |url=https://www.cmog.org/glass-dictionary/acid-etching | |url=https://www.cmog.org/glass-dictionary/acid-etching | ||

| | |

|access-date=2018-05-28}}</ref> ] or cutting glass refers to using a tool to carve into the glass.<ref name="FitzwilliamMuseum">{{cite web | ||

| |title=The Fitzwilliam Museum: Techniques of Glass Engraving | |title=The Fitzwilliam Museum: Techniques of Glass Engraving | ||

| |publisher=University of Cambridge | |publisher=University of Cambridge | ||

| |url=http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/glassengravers/techniques.html | |url=http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/glassengravers/techniques.html | ||

| |access-date=2018-05-28|date=2010-06-14 | |||

| |accessdate=2018-05-28}}</ref>|group=Note}} Some of the most successful Fostoria patterns were ''American'', ''Kashmir'', ''June'', ''Trojan'', and ''Versailles''.<ref name="Prisant93"/> One pattern that should be easy for historians to remember is pattern 1861. The pattern was named ''Lincoln'', and 1861 is the year ] became ].<ref name="CGJ12030716">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=The New York Crockery and Glass District(2nd page, right column)|url= |magazine=Crockery and Glass Journal <!-- Page 16 -->|location= |publisher=Whittemore and Jaques, Inc. |date=1912-03-07 |access-date= }}</ref> The pattern was used for pressed tableware. It was pictured on the front page of the Crockery and Glass Journal on January 4, 1912.<ref name="CGJ12010401">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Crockery and Glass Journal (front page), Fostoria Quality Excels|url= |magazine=Crockery and Glass Journal <!-- Page 16 -->|location= |publisher=Whittemore and Jaques, Inc. |date=1912-01-04 |access-date= }}</ref> | |||

| }}</ref>|group=Note}} Some of the most successful Fostoria patterns were ''American'', ''Kashmir'', ''June'', ''Trojan'', and ''Versailles''.<ref name="Prisant93"/> Pattern 1861 was named ''Lincoln'', and 1861 is the year ] became ].<ref name="CGJ12030716">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=The New York Crockery and Glass District (2nd page, right column)|magazine=Crockery and Glass Journal <!-- Page 16 -->|publisher=Whittemore and Jaques, Inc. |date=1912-03-07 }}</ref><ref name="LOCLincolnInaug">{{cite web | |||

| |title=Abraham Lincoln's Inauguration March 4, 1861 | |||

| |website= America's Story from America's Library | |||

| |publisher=Library of Congress | |||

| |url=http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/civil/jb_civil_lincoln2_1.html | |||

| |access-date=2020-01-07}}</ref> The pattern was used for pressed tableware. It was pictured on the front page of the Crockery and Glass Journal on January 4, 1912.<ref name="CGJ12010401">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Crockery and Glass Journal (front page), Fostoria Quality Excels|magazine=Crockery and Glass Journal <!-- Page 16 -->|publisher=Whittemore and Jaques, Inc. |date=1912-01-04 }}</ref> | |||

| From the beginning of the Moundsville operations until about 1915, Fostoria focused on oil lamps and products for restaurants and bars—especially stemware and tumblers.<ref name="Venable174" |

From the beginning of the Moundsville operations until about 1915, Fostoria focused on oil lamps and products for restaurants and bars—especially stemware and tumblers.<ref name="Venable174"/> In 1915, Fostoria introduced its ''American'' pattern (pattern number 2056). This glass pattern was used for stemware and tableware, and continued to be produced until 1988.<ref name="Sullivan188">{{harvnb|Sullivan|2010|p=188}}</ref> Described as "block geometric", its appearance was very different from other patterns when it was introduced. Most glass made with the ''American'' pattern was produced using Fostoria's high-quality crystal formula.<ref name="Warmans37">{{harvnb|Schroy|Meyer|2017|p=37}}</ref> ''American'' became Fostoria's most famous pattern.<ref name="Long6-8">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=6–8}}</ref> Management around this time was still led by W. A. B. Dalzell as company president. Vice president was C. B. Roe, and A. C. Scroggins Jr. was the secretary and treasurer. W. S. Brady was still listed as on the board of directors.<ref name="Moody1916P2634">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Fostoria Glass Co|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IH03AQAAMAAJ&q=Fostoria+Dalzell+roe&pg=PA2634 |magazine=Moody's Manual of Railroads and Corporation Securities 1916 Vol. III <!-- Page 2634 -->|location= New York|publisher=Moody Publishing Company |date=1916 |access-date=2008-05-11 }}</ref> | ||

| ] diminished the market for commercial barware, causing Fostoria to put more emphasis on tableware for the home. Their initial target market was the higher-quality portion of the home market.<ref name="Venable174"/> In 1924, the company became the first glass manufacturer to produce complete dinner sets in crystal ware.<ref name="Schramm4">{{harvnb|Schramm|2004|loc=Ch. 4 of e-book}}</ref> In 1925, the company introduced dinnerware in colors. A national advertising campaign was started in 1926 to promote the complete dinnerware sets.<ref name="Sullivan188"/> Fostoria was also a major contributor to the creation of the ].<ref name="Sullivan188"/> Clear and pastel dinner sets became very popular, although expensive. This led to low cost dinner sets being made by injecting molten glass into an automated pressing mold. The product often had minor flaws, so "lacy" patterns were often included in the mold, or etched onto the glass, to hide imperfections.<ref name="Kovel3"/> | ] diminished the market for commercial barware, causing Fostoria to put more emphasis on tableware for the home. Their initial target market was the higher-quality portion of the home market.<ref name="Venable174"/> In 1924, the company became the first glass manufacturer to produce complete dinner sets in crystal ware.<ref name="Schramm4">{{harvnb|Schramm|2004|loc=Ch. 4 of e-book}}</ref> In 1925, the company introduced dinnerware in colors. A national advertising campaign was started in 1926 to promote the complete dinnerware sets.<ref name="Sullivan188"/> Fostoria was also a major contributor to the creation of the ].<ref name="Sullivan188"/> Clear and pastel dinner sets became very popular, although expensive. This led to low cost dinner sets being made by injecting molten glass into an automated pressing mold. The product often had minor flaws, so "lacy" patterns were often included in the mold, or etched onto the glass, to hide imperfections.<ref name="Kovel3"/> | ||

| By 1926, the company had 10,000 different items in its catalog, and employment before the Depression peaked around 650 people.<ref name="Venable174"/> Among the etching patterns introduced by Fostoria during the 1920s were ''June'', ''Versailles'', and ''Trojan''. The ''June'' pattern, which was made from 1928 to 1951, was etched on stemware and tableware.<ref name="Long9293">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=92–93}}</ref> It is one of the rare patterns that can be dated based on color of the glass.<ref name="Kovel48">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=48}}</ref> The ''Versailles'' pattern, made from 1928 to 1943, was another etching pattern. The etchings were mostly on plates and dishes. The glass product with the etching was made in many colors.<ref name="Kovel8687">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|pp=86–87}}</ref> The etching pattern called ''Trojan'' was made from 1929 to 1943. The ''Trojan'' etchings were mostly on plates and dishes. Original glass colors were rose and topaz. Gold tint was used in some of the last years of production.<ref name="Kovel85">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=85}}</ref> By 1928, Fostoria was the largest producer of handmade glass in the nation.<ref name="Sullivan188"/> | By 1926, the company had 10,000 different items in its catalog, and employment before the Depression peaked at around 650 people.<ref name="Venable174"/> Among the etching patterns introduced by Fostoria during the 1920s were ''June'', ''Versailles'', and ''Trojan''. The ''June'' pattern, which was made from 1928 to 1951, was etched on stemware and tableware.<ref name="Long9293">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=92–93}}</ref> It is one of the rare patterns that can be dated based on color of the glass.<ref name="Kovel48">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=48}}</ref> The ''Versailles'' pattern, made from 1928 to 1943, was another etching pattern. The etchings were mostly on plates and dishes. The glass product with the etching was made in many colors.<ref name="Kovel8687">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|pp=86–87}}</ref> The etching pattern called ''Trojan'' was made from 1929 to 1943. The ''Trojan'' etchings were mostly on plates and dishes. Original glass colors were rose and topaz. Gold tint was used in some of the last years of production.<ref name="Kovel85">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=85}}</ref> By 1928, Fostoria was the largest producer of handmade glass in the nation.<ref name="Sullivan188"/> | ||

| ===Depression and |

===Depression and post-war=== | ||

| ] for Fostoria's ''Chintz'' pattern|alt=advertisement for stemware]]During the Great Depression the company made glassware for the higher and lower cost segments of the market. Two popular Fostoria etching patterns were ''Navarre'' and ''Chintz''. ''Navarre'' was made from 1937 until 1980. Some of the pieces were etched onto the ''Baroque'' glass pattern, but others were on more modern glass patterns. The product was originally made in crystal, but later on a few pieces with color.<ref name="Kovel58">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=58}}</ref> The ''Baroque'' glass pattern was made by Fostoria from 1937 to 1965, and used for stemware and many types of tableware.<ref name="Long1618">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=16–18}}</ref> The ''Chintz'' pattern was made from 1940 to 1973. This etching pattern is a drawing of branches leaves and flowers, and was usually on the ''Baroque'' glass pattern.<ref name="Kovel26">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=26}}</ref> The ''Colony'' pattern discussed earlier was introduced around this time.{{#tag:ref|Long and Seate list the ''Colony'' pattern (number 2412) as manufactured from 1940 to 1973.<ref name="Long53">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|p=53}}</ref> Schroy says the pattern was produced from the 1930s to 1983.<ref name="WarmansFG124"/>|group=Note}} Another long-lived glass pattern, ''Century'', was introduced in 1949 and made until 1982. It was used for stemware and tableware.<ref name="Long46">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|p=46}}</ref> Advertising during the 1940s included photos in the Ladies Home Journal.<ref name="NameIt">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Yours, for a toast to charm (advertisement) |

] for Fostoria's ''Chintz'' pattern|alt=advertisement for stemware]]During the Great Depression the company made glassware for the higher and lower cost segments of the market. Two popular Fostoria etching patterns were ''Navarre'' and ''Chintz''. ''Navarre'' was made from 1937 until 1980. Some of the pieces were etched onto the ''Baroque'' glass pattern, but others were on more modern glass patterns. The product was originally made in crystal, but later on a few pieces with color.<ref name="Kovel58">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=58}}</ref> The ''Baroque'' glass pattern was made by Fostoria from 1937 to 1965, and used for stemware and many types of tableware.<ref name="Long1618">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=16–18}}</ref> The ''Chintz'' pattern was made from 1940 to 1973. This etching pattern is a drawing of branches leaves and flowers, and was usually on the ''Baroque'' glass pattern.<ref name="Kovel26">{{harvnb|Kovel|Kovel|1991|p=26}}</ref> The ''Colony'' pattern discussed earlier was introduced around this time.{{#tag:ref|Long and Seate list the ''Colony'' pattern (number 2412) as manufactured from 1940 to 1973.<ref name="Long53">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|p=53}}</ref> Schroy says the pattern was produced from the 1930s to 1983.<ref name="WarmansFG124"/>|group=Note}} Another long-lived glass pattern, ''Century'', was introduced in 1949 and made until 1982. It was used for stemware and tableware.<ref name="Long46">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|p=46}}</ref> Advertising during the 1940s included photos in the Ladies Home Journal.<ref name="NameIt">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title=Yours, for a toast to charm (advertisement) |magazine=Ladies' Home Journal <!-- Page 18 -->|location=Philadelphia, PA |publisher=The Curtis Publishing Company |date=April 1948 }}</ref> | ||

| Production peaked in 1950 when Fostoria's 1,000 employees manufactured over 8 million pieces of glass and crystal. A combination of |

Production peaked in 1950 when Fostoria's 1,000 employees manufactured over 8 million pieces of glass and crystal. A combination of quality products and national advertising helped the company continue to be the largest manufacturer of handmade glassware in the United States. Every American president from ] through ] had glassware made by Fostoria.<ref name="Schramm4"/> Long-lived patterns introduced during the 1950s included ''Rose'', ''Wedding Ring'', and ''Jamestown''. ''Rose'' was a cutting on stemware and tableware, and it was produced from 1951 to 1973.<ref name="Long141">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|p=141}}</ref> ''Wedding Ring'' was a decoration on stemware and tableware that was produced from 1953 to 1975. ''Jamestown'' was a glass pattern for stemware and tableware, and was used for numerous products from 1958 to 1982. The glass used was crystal and seven colors of glass: amber, blue, green, pink, amethyst, brown, and ruby. Among ''Jamestown'' stemware, ruby is valued higher than other colors by collectors.<ref name="Long9091">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=90–91}}</ref> Among the milk glass patterns, ''Vintage'' was used for tableware and a few types of stemware from 1958 to 1965.<ref name="Long181">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|p=181}}</ref> | ||

| In the 1960s and 1970s, the company's marketing campaign expanded to include boutiques and display rooms within jewelry and department stores. Fostoria's top customer in 1971 was ]. It was Marshall Field's that had created a bridal registry in 1935, which was important to manufacturers of tableware for the home.<ref name="Venable305">{{harvnb|Venable|Jenkins|Denker|Grier|2000|p=305}}</ref> Fostoria also published its own consumer direct magazine, "Creating with Crystal" during the 1960s and 1970s.<ref name="Rinker97">{{harvnb|Rinker|1997|p=97}}</ref> The ''Woodland'' glass pattern, not to be confused with the ''Woodland'' etching from the 1920s, was introduced in 1975 and made until 1981.<ref name="Long188189">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=188–189}}</ref> | In the 1960s and 1970s, the company's marketing campaign expanded to include boutiques and display rooms within jewelry and department stores. Fostoria's top customer in 1971 was ]. It was Marshall Field's that had created a bridal registry in 1935, which was important to manufacturers of tableware for the home.<ref name="Venable305">{{harvnb|Venable|Jenkins|Denker|Grier|2000|p=305}}</ref> Fostoria also published its own consumer direct magazine, "Creating with Crystal", during the 1960s and 1970s.<ref name="Rinker97">{{harvnb|Rinker|1997|p=97}}</ref> The ''Woodland'' glass pattern, not to be confused with the ''Woodland'' etching from the 1920s, was introduced in 1975 and made until 1981.<ref name="Long188189">{{harvnb|Long|Seate|2003|pp=188–189}}</ref> | ||

| ===Morgantown=== | ===Morgantown=== | ||

| In 1965, Fostoria purchased the Morgantown Glassware Guild, which had also been known as the Morgantown Glass Works. First Lady ] had chosen Morgantown glassware for official ] tableware, and Fostoria sought to capitalize on this. |

In 1965, Fostoria purchased the Morgantown Glassware Guild, which had also been known as the Morgantown Glass Works. Morgantown was a leader in barware and also made tableware. First Lady ] had chosen Morgantown glassware for official ] tableware, and Fostoria sought to capitalize on this. Glassware from Morgantown could be sold as stylish entry-level tableware for the home. This segment was profitable for Fostoria for only two years, as department stores eliminated secondary sources and restaurants began switching to machine-made glass. Fostoria closed the Morgantown factory in 1971.<ref name="Venable177178">{{harvnb|Venable|Jenkins|Denker|Grier|2000|pp=177–178}}</ref> | ||

| ==Decline== | ==Decline== | ||

| ] |

]In 1950, company president David B. Dalzell had said the Fostoria's competition came from "three sources: other companies in the domestic trade, imports, and automatic machinery."<ref name="Venable174"/> During the 1970s, changing preferences and a substantial increase in imports of machine-made lead-crystal tableware forced the company to make significant investments in machinery. This late attempt to be more competitive by automating more of the manufacturing process unsettled the labor force, and the company faced ]s during the early 1970s. By 1980, the company's commercial division was unprofitable.<ref name="Venable178">{{harvnb|Venable|Jenkins|Denker|Grier|2000|p=178}}</ref> | ||

| In 1983, Fostoria sold its |

In 1983, Fostoria sold its factory to Lancaster Colony Corporation of ]. However, Lancaster Colony shut down the Fostoria Glass factory permanently on February 28, 1986. At the time, Kenneth B. Dalzell, the fourth generation of Dalzells at Fostoria Glass, was head of Fostoria operations.<ref name="Paquette183"/> Dalzell purchased the assets of Viking Glass company of ] in April 1987, and renamed the company Dalzell-Viking.<ref name="AGR">{{cite magazine |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |title= |magazine=American Glass Review <!-- Page 18 -->|publisher=Commoner Publishing Company |date=1988 }}</ref> Fostoria inventory and molds were sold to several companies, and Dalzell-Viking was one of the purchasers.<ref name="Lechner67"/> The ''American'', ''Baroque'', and ''Coin'' patterns were thereafter produced by others, including Dalzell-Viking. Some of this glassware produced at Dalzell-Viking was made by former Fostoria employees using Fostoria molds—making it difficult to differentiate from glassware made at the Fostoria plant.<ref name="Sullivan188"/> Dalzell-Viking closed in 1998.<ref name="Schroy244">{{harvnb|Schroy|2001|p=244}}</ref> | ||

| == Popular patterns == | |||

| === '''''American Pattern #2056''''' === | |||

| The most well-known and distributed pattern made by Fostoria was “''American''”. The ''American'' pattern of tableware was introduced in 1915 and was to become incredibly successful and profitable for the Fostoria Glass Co. Items of the pattern were still being produced at the time of Fostoria’s factory closing in 1986. The pattern is identifiable by its characteristic “cubist- prismatic” detailing. Pieces of ''American'' were made by craftsmen and described in company literature as “hand-molded and flame-tempered”. The ''American'' pattern was designed by Phillip Ebeling, an employee of the Fostoria Glass Company at the time. The original design patents #47,284 and #47,285 were applied for in June 1914 and assigned to the Company in March and May of 1915. | |||

| Over 300 individual pieces of this pattern were made and sold over its 71 years of production by the Fostoria Glass Company, although not all items were made for the entire duration of the pattern. It was not only the largest of the patterns made by Fostoria, but was by far its longest and most diverse pattern produced. | |||

| The vast majority of the ''American'' pattern was produced in only crystal (clear) glass. Many of the boudoir items were produced in the colors of canary, blue, amber and green in the 1920s. A small selection of items from this pattern were produced in milk glass in the 1950s and items in ruby were made in the 1980s. Items can be found in sampled colors and with lusters (staining) but these are hard to find. | |||

| The ''American'' pattern’s detailing was widely copied by other glass manufacturers, both in the United States and in Europe. Some of the original ''American'' pattern moulds were sold to several other glass manufacturers upon the close of the Fostoria factory in 1986 to firms such as Dalzell-Viking, Fenton Glass Co., and currently, Mosser Glass where items are still being made today (2019) using these original moulds. | |||

| === '''''Pioneer Pattern #2350''''' === | |||

| Introduced in 1926, the ''Pioneer'' pattern was the first full dinnerware pattern produced in glass by any manufacturer. This revolutionary concept of offering a glass dinnerware set as an alternative to china was widely advertised and marketed directly to the consumer by the Fostoria Glass Company in full color magazine advertisements. Direct to the consumer advertising was also an innovation for the glass industry by the Fostoria Glass Company. | |||

| The ''Pioneer'' pattern was offered in amber, green and blue colors as well as in crystal. Plates, platters and serving bowls were included in the pattern; in fact, every item to serve from “soup to nuts” with ashtrays thrown in to accommodate the new trend of smoking at the table. | |||

| The ''Pioneer'' pattern served as the “blanks” or base shapes for the first plate etched dinnerware patterns including ''#273 Royal'' (designed by Edgar Bottome-issued design pat 68,424 and 68,425 in 1925), ''#274 Seville, #275 Vesper'' (designed by Edgar Bottome-issued design pat 70,356 and 70,357 in 1926) and ''#276 Beverly'' (designed by Edgar Bottome-issued design pat 72,816 and 72,817 in 1927) which were all offered in the colors of the ''Pioneer'' pattern through 1933. The ''Pioneer'' pattern was discontinued after 1943. | |||

| === '''''Fairfax Pattern #2375''''' === | |||

| The ''Fairfax'' pattern introduced in 1927 was a larger and more complete dinnerware line with at least 66 pieces. The ''Fairfax'' pattern is faceted where the ''Pioneer'' pattern was not. Other line items were often used to accompany the ''Fairfax'' pattern including the #5000 Jug, #2378 ice bucket, whipped cream pail and sugar pail and #2429 service tray & insert. | |||

| ''Fairfax'' was made in amber, azure, green, orchid, rose, topaz/gold tint and crystal. It was also offered with the Mother of Pearl iridescent treatment. The tea sugar and cream were made in ebony and ruby as well as the other colors. A few additional items of ''Fairfax'' were also made in ebony. | |||

| It served as the blank for the very popular plate etched patterns of ''#277 Vernon'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design pat 76,852 & 76913 in 1928), ''#278 Versailles'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design pat 76,372 & 76454 in 1928), ''#279 June'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design pat 76,373 & 76455 in 1928), ''#280 Trojan'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design pat 79,226 & 79,227 in 1929) plus ''#282 Acanthus'' and ''#283 Kashmir''. | |||

| The ''Fairfax'' dinnerware pattern in colors was available through 1940, in crystal through 1943 with a few serving pieces remaining available through 1959. | |||

| === '''''#4020 Stemware'' Line & It’s Complementary ''Mayfair Pattern #2419''''' === | |||

| The square base tumblers and goblets of the ''#4020 line'' with the square shape of the complementary ''#2419 Mayfair'' line revolutionized American dinnerware design. Both of these patterns were designed by George Sakier, an independent industrial designer, who had a business relationship with the Fostoria Glass Company from at least 1926 – 1978. These patterns were the first American made glass tableware designs to be copied and sold in Europe, which until that time had always been the trend setter in this category of design. | |||

| The ''#4020 line'' of tumblers was introduced in 1929 with the ''Mayfair'' dinnerware pattern introduced in 1930. The sherbet and tumbler designs for the ''#4020 line'' (George Sakier design pat 80,972 & 81,302 of 1930) and the accompanying #4021 finger bowl (George Sakier design pat 80,971 in 1930) were followed with a design patent by Edgar Bottome for the stemmed goblet design in this pattern (pat 83,494 from March 3, 1931). Other items also produced in this pattern are a decanter, jug, sugar & cream. | |||

| The ''#4020 line'' was offered on either solid crystal or in combinations of color bases with crystal bowls or color bowls and crystal bases. The base color options included amber, ebony, green or wisteria. The bowl color options included rose, topaz/gold tint and wisteria. The etched patterns produced on the ''#4020 line'' include ''#283 Kashmir'', ''#284 New Garland'', ''#285 Minuet'', ''#305 Fern, #306 Queen Anne & #307 Fountain''. The cutting patterns produced include ''#195 Millefleur'' (designed by George Sakier – issued design pat 81,301 in 1930), Cutting ''#700 Formal Garden'', Cutting ''#701 Tapestry'', Cutting ''#702 Comet'', Cutting ''#703 New Yorke''r, Cutting ''#773 Rhythm'', Cutting ''#783 Chelsea''. Decorations ''#603 Club Design A'', decoration ''#604 Club Design B'', decoration ''#605 Saturn'', decoration ''#607 Polka Dot'', decoration ''#611 Club Design C'' and decoration ''#612 Club Design D'' were also produced on the ''#4020'' blanks. | |||

| The ''#2419 Mayfair'' pattern with its square shape and scalloped corners was introduced in 1930. As mentioned earlier, it was designed by George Sakier, an industrial designer who had a 50+ year relationship with the Fostoria Glass Company. Its shape is definitely Art Deco and was all the fashion at the time of its introduction. According to Milbra Long & Emily Seate, authors of a series of books on the Fostoria Glass Company, the name of this pattern reflected the “smartest residential section of London”. | |||

| The ''Mayfair'' pattern was a complete dinnerware service with 49 items in the pattern. This pattern was produced from 1930 – 1940 with a few items continuing until 1943. It was produced in crystal, amber, azure, ebony, green, rose, topaz/gold tint and wisteria. Some items in this pattern were also produced in Silver Mist, Fostoria’s brand name for frosted glass. The individual ashtray and the tea cream & sugar in the ''Mayfair'' line were also produced in the jewel tone colors of regal blue, empire green and burgundy. Only the ashtray and 4-part relish were produced in ruby. | |||

| Among the etched patterns which used the ''#4020'' stemware and ''#2419 Mayfair'' patterns as their base are: ''#284 New Garland'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design pat 83,893 in 1930), ''#285 Minuet'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design pat 83,788 in 1930) ''#286 Manor'', ''#305 Fern, #306 Queen Anne,'' and ''#307 Fountain''. The ''#308 Wildflower'' etch is found on a variety of blanks, including some from the #2419 ''Mayfair'' pattern. | |||

| === '''''Baroque Pattern #2496'' with Accompanying #2484 Items''' === | |||

| The ''Baroque'' dinnerware line was introduced to be available for the Fostoria Glass Company’s Golden Jubilee in 1937. Most of the items in the line were introduced in 1936 and 1937 and feature a prominent fleur-de-lis raised design with a scalloped edge or a spread feather stem or handles and knob designs. | |||

| There are two known designers involved in the creation of this pattern; George Sakier (issued design patents 91,686, 91,687, 91,688, & 91,909 in 1934; design patent 94,442 in 1935 and design patent 103,058 in 1937) and Edgar Bottome (issued design patent 102,742 and 102,744 in 1937). The Sakier design patents are primarily for the ''#2484 line'' items which encompass several candle holders and a bowl, but also the #2496 single and trindle candlesticks. Additional royalty reports for payments to contract designer George Sakier document his design of additional pieces in the line including both the 7” and 8” vases, the jelly & cover, the preserve & cover and the comports. The internal design department designer, Edgar Bottome’s patents are for the plate and the goblet. | |||

| The ''Baroque'' pattern has 89 individual items including the stems and tumblers. This is the first dinnerware pattern to have its own stemware line incorporated into it using the same pattern number. The ''#2484 line'' item pieces started to appear in 1934 and 1935 and were incorporated into the ''Baroque'' pattern when it was introduced in 1936. Many items were added in 1937 in the limited color pallet of crystal, azure and topaz which was renamed gold tint in the 1937 golden jubilee year. There were also pieces of the ''Baroque'' pattern made in azure tint which is a more greenish variation of the color azure. This new color was introduced to the trade in ''China, Glass & Lamps'' Aug. 1936 issue. | |||

| A few pieces of the line including the #2484 10” bowl, #2484 2 lite candlestick and the #2496 trindle candlesticks were offered in silver mist with the #2484 bowl and #2496 trindle candlestick also offered in amber and green. Only the #2496 trindle candlestick was made in the additional “jewel tone” colors of burgundy, empire green, regal blue and ruby. | |||

| The ''Baroque'' pattern served as the one of the primary blanks for many of the Master Etchings introduced in the mid-1930s. Among these patterns are Plate Etching ''#327 Navarre'' designed by Edgar Bottome in 1936; Plate Etching ''#328 Meadow Rose''; Plate Etching ''#329 Lido'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design patents 104,717 and 104,718 in 1937); Plate Etching ''#331 Shirley'' (designed by Edgar Bottome – issued design patent 107,637 in 1937) and Plate Etching ''#338 Chintz''. The ''Navarre'' pattern was the longest lived and best known of Fostoria’s etching patterns and dominated the Bridal Registry market for over two decades. Items in the ''Navarre'' pattern were still being produced in 1982 when blown wares were discontinued by the Fostoria Glass Company. The Navarre pattern was then produced by Lenox Inc. for a few more years until approximately 1990. | |||

| === '''''Colony Pattern #2412''''' === | |||

| The ''Colony'' dinnerware pattern was second only to the ''#2056 American'' pattern in popularity and size with 130 items in the line including a full offering of stems and tumblers. It was introduced in 1938, expanded in the 1940s, with some pieces still being made in crystal in 1975. It was one of the two pattern “mainstays” of the Fostoria Glass Company’s production during WWII and long after. The pattern #2412 was originally utilized for the 9-piece limited ''Queen Anne'' pattern which was available only in 1926 – 1927. Most of the items from this line were later incorporated into the ''Colony'' pattern which carried the same number. It is distinguished by its swirl design, most pieces having the overall swirl element, others with only the rims having a swirl design with the remaining portion plain. | |||

| One of the principle designers of the ''Colony'' pattern was contract designer George Sakier (issued design patents 115,801 in 1939; 125,291 and 125,574 in 1941) for the oblong pickle dish, goblet & plate. Marvin Yutzey of the internal design department of Fostoria is another of the designers of this pattern (issued design pat 155,758 and 155,759 in 1949; 157,114 in 1950) for the covered butter, cereal pitcher and bowl. Fostoria Glass Company royalty records for George Sakier also attribute the following ''Colony'' pattern items to his design: square ashtrays, small ashtray, large ash tray, round ashtrays, individual ashtray, cigarette box & cover, olive, celery, 2 and 3 part oblong relishes, low comport & cover, footed tid-bit, divided sweetmeat, mayonnaise & plate, sherbet, tumblers, sugar & cream tray, ice bowl, 7” vase-flared & cupped, ice jug, cocktail, wine & oyster cocktail. | |||

| The complementary ''#5412 Colonial Dame'' line of blown stemware was designed by Marvin Yutzey (issued design patents 155,760 and 155,761 in 1949). This stemware design was offered with either an empire green bowl, crystal base or in all crystal. | |||

| The ''Queen Anne'' era of the #2412 line was produced in the mid-1920s colors of amber, blue and green as well as crystal. The ''#2412 Colony'' dinnerware line was available only in crystal. In the 1950s a few pieces were made in milk glass including the traditional white, aqua and peach colors. In 1981-1982 the sugar, cream and bud vase were offered in ruby. Also in 1981-1982, the ''Maypole Giftware'' line, comprised of 5 items of #2412 was available in the colors of light blue, peach and yellow. | |||

| === '''''Century Pattern #2630''''' === | |||

| The ''Century'' pattern was the first new dinnerware pattern introduced after WWII in 1949 and 1950. It remained in production from that time until 1982, the end of the hand finished manufacturing process at the Fostoria Glass factory. This dinnerware pattern had a total of 85 pieces (including covers and stems) which was considerably smaller than its immediate predecessor the ''#2412 Colony'' pattern. Entertaining styles had simplified after the second world war so fewer serving pieces were required for the table. | |||

| The principle designer of the ''Century'' pattern was Marvin Yutzey of Fostoria’s internal design department (issued design patents 155,762 & 155,763 in 1949; 159,768 & 160,356 in 1950 and 163,435 & 164,345 in 1951). These patented designs included the plate, the handled plate, the trindle candelabra, the cereal pitcher, the goblet and the sherbet. | |||

| The ''Century'' pattern was produced only in crystal and is characterized by a scalloped edge, reverse C handles and a “dollop” knob on covers and stoppers. The surfaces of the pieces are plain and lent themselves to being the blank for the popular 1950s plate etching patterns of ''#342 Bouquet, #343 Heather'' which was designed by Frank Helms of the internal design department (issued design patent 158,576 and 156,625 in 1950), ''#344 Camelia'' and ''#345 Starflower''. The ''Century'' blank was also used on ''Crystal Print 6 Lacy Leaf'' pattern available in 1957 – 1958. And ''#2630 Century'' was the basis for the cutting patterns ''#823 Sprite'' designed by Marvin Yutzey (issued design patent 160,452 in 1950) and ''#833 Bridal Wreath.'' | |||

| === '''''Coin Pattern #1372''''' === | |||

| Fostoria introduced the ''#1372 Coin'' pattern in 1958 but the line carries the same line number as the 1905 pressed glass pattern called ''Essex''. The shapes of many of the Coin pattern pieces are based on items from this earlier pattern or are variations on them, all with the Fostoria coins added to the moulds. Those pieces include the covered sugar, sugar, cream, comports, oval bowl, handled nappy and tumblers. The remainder of the pattern consisted of newly designed items that would not have been part of the Essex line in 1905 such as candlesticks, smoking items and lamps to name a few. Both Long & Seate in ''Fostoria Tableware 1944 – 1986'' and Ronald & Sunny Stinson in their booklet ''#1372 Line Coin Glass Handcrafted by Fostoria'' mention that “fourteen craftsmen combined their glassmaking skills to bring about this new glass line…”, but neither source provides any detail as to who these craftsmen might have been. The cigarette box, round and oblong ashtrays appear to be variations of George Sakier’s ''#2731 line'' items with the coins being the only difference. There is also a drawing in the Sakier files of the archive of Jon Saffell, last director of design for the Fostoria Glass Company, of the ''Coin'' pattern courting lamp which provides another clue to a possible Sakier involvement in the design of some items of this line. | |||

| The ''Coin'' pattern was not a full dinnerware line but it did include an 8-inch plate as well as tumblers and stems and many table serving pieces. The coins of this pattern do not mimic real currency as that is illegal and was the basis for the original ''Coin'' pattern made by U.S. Glass Co. to be pulled from the market in 1892. There are four (4) coin designs; an Eagle, a Liberty Bell, a Torch and a Colonial Head. Two of these designs carry the date of 1887, the founding year of the Fostoria Glass Company. | |||

| The ''Coin'' pattern was initially introduced in crystal only with amber and blue added in 1961, green (emerald green) in 1963, olive green replaced green in 1965 and ruby was added to the line in 1967 while the blue color was dropped. Blue, but a different blue color, was added back in the offering for the ''Coin'' pattern in 1975. A few of the crystal pieces were decorated with gold coins in the early 1960s. | |||

| Variations of the ''Coin'' pattern were made for the Avon Company who used the items as awards for their sales personnel. And a Canadian Centennial version, with Canadian designed coins and an 1867 date, was also produced in 1967. | |||

| === '''''Jamestown Pattern #2719''''' === | |||

| The ''Jamestown'' pattern was introduced in 1958 in honor of the 350<sup>th</sup> anniversary of the first glass manufacturing operation in the new world at the Jamestown Colony in Virginia. The leadership of the Fostoria Glass Company, along with those of many of the other primary glass manufacturers of the time, established the Jamestown Glasshouse Foundation, Inc. in 1957 which built and staffed a replica glasshouse at the Jamestown Festival Park for the 350<sup>th</sup> anniversary celebrations. | |||

| Early American design was becoming very popular across the U.S. in the late 1950s and the Fostoria Glass Company decided to participate in that trend by designing the Jamestown pattern which is much in line with both Early American design and the growing tendency for dining to be more casual. The designer for the ''Jamestown'' pattern was the well-regarded contract designer George Sakier. | |||

| This pressed glass pattern was in production from 1958 – 1973 with stemware and plates in some colors still being made in 1982. This limited tableware line of 26 items had only an 8-inch plate, serving pieces, the stemware and tumblers. Some of the serving pieces were discontinued as early as 1966 and prove more challenging for the collector to find. | |||

| ''Jamestown'' was produced in crystal, amber, amethyst, blue, brown, green, pink and ruby. Ruby pieces were only made for the stems, tumblers, dessert bowls and plates. Crystal, amber, blue and green were introduced in 1958, amethyst and pink in 1959, brown in 1961 and ruby in 1964. The new tone of green created by Fostoria for the ''Jamestown'' pattern mimicked the color of the green glass made at the Jamestown Colony. | |||

| The ''Jamestown'' pattern was heavily advertised by the Fostoria Glass Co. as the best option available to the new bride for either the casual dining or daytime table setting. The bridal market was encouraged to chose both a casual dining pattern and a formal, blown ware stem pattern for their registry and the ''Jamestown'' pattern was the staple casual pattern featured. | |||

| === '''''Heirloom Pattern''''' === | |||

| Introduced in 1959, the ''Heirloom'' pattern is comprised of many different line numbers. It represents a dramatic departure from the traditional dinnerware and tableware lines the Fostoria Glass Company had relied on for decades but which had declined in popularity by the end of the 1950s. ''Heirloom'' was classified as a “decorator line” comprised of bowls, candlesticks, epergnes, plates and vases. Today it would be considered “mid-century modern” in style. Each piece was made in a “free-form” shape resulting in individual differences in each item made. | |||

| As mentioned earlier, the ''Heirloom'' pattern was comprised of many different line numbers which can be partially explained from the reuse of the moulds of several much older Fostoria Glass Co. pressed glass patterns which were modified by the “free-form” finishing process. The ''#1002'' vases used a 1901 bouquet holder mould; the #1229 bud vase is from the 1903 ''Frisco'' pattern; the #1515 items from the 1907 ''Lucere'' pattern; the #2183 pieces from the 1918 ''Colonial Prism'' pattern; the #2570 from the 1961 ''Sculpture'' pattern. The remainder of the line numbers in the ''Heirloom'' pattern were newly created in 1959. | |||

| The ''Heirloom'' pattern pieces were made in the opalescent colors of blue, green, opal, pink and yellow plus ruby and bittersweet (orange). The pattern was in production through 1970, but not all colors or items were made for the duration of the pattern. The yellow opalescent color was only made from 1959 – 1962; the Bittersweet color only from 1960 - 1962. Ruby was added to the line in 1961, but not in all items of the pattern. The 18 inch and 24 inch vases were made only in 1959 and the 11 inch winged vase only in 1960, making these pieces particularly collectible. | |||

| '''Reference Sources for popular patterns''' | |||

| U.S. government patent records via google/patents.com | |||

| Fostoria Glass Company Catalogs & Price Lists | |||

| Fostoria Glass Company royalty reports to designers | |||

| Milbra Long & Emily Seate, ''Fostoria Tableware 1924 – 1943,'' Paducah, KY: Collector Books, 1999 | |||

| Long & Seate, ''Fostoria Tableware 1944 – 1986,'' Paducah, KY: Collector Books, 1999 | |||

| Long & Seate, ''Fostoria Stemware, 2<sup>nd</sup> Edition,'' Paducah, KY: Collector Books, 2008 | |||

| Ronald & Sunny Stinson, ''#1372 Line Coin Glass Handcrafted by Fostoria,'' San Angelo, TX: Fostoria Glass Society of North Texas, 1988 | |||

| Hazel Marie Weatherman, ''Fostoria Its First Fifty Years,'' Springfield, MO: The Weatherman’s, 1972 | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 297: | Line 187: | ||

| ===References=== | ===References=== | ||

| {{refbegin| |

{{refbegin|20em}} | ||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| |last = Fones-Wolf | |last = Fones-Wolf | ||

| |first =Ken | |first =Ken | ||

| |author-link = | |||

| |title = Glass towns: industry, labor and political economy in Appalachia, 1890–1930s | |title = Glass towns: industry, labor and political economy in Appalachia, 1890–1930s | ||

| |publisher = University of Illinois Press | |publisher = University of Illinois Press | ||

| |year = 2007 | |year = 2007 | ||

| |location = Urbana, IL | |location = Urbana, IL | ||

| |page = | |||

| |url = | |||

| |oclc = 69792081 | |oclc = 69792081 | ||

| |isbn =978-0-252-03131-1 | |isbn =978-0-252-03131-1 | ||

| |ref=harv | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| | |

| last1 = Kovel | ||

| | |

| first1 = Ralph M. | ||

| | author-link = | |||

| | last2 = Kovel | | last2 = Kovel | ||

| | first2 = Terry H. | | first2 = Terry H. | ||

| Line 323: | Line 208: | ||

| | location = New York | | location = New York | ||

| | pages = 250 | | pages = 250 | ||

| | oclc = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-51758-444-6 | | isbn = 978-0-51758-444-6 | ||

| |

}} | ||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| |last1 = Lechner | |last1 = Lechner | ||

| Line 331: | Line 215: | ||

| |last2 = Lechner | |last2 = Lechner | ||

| |first2 =Ralph | |first2 =Ralph | ||

| |author-link = | |||

| |title = The World of Salt Shakers: Antique & Art Glass Value Guide, Volume 3 | |title = The World of Salt Shakers: Antique & Art Glass Value Guide, Volume 3 | ||

| |publisher = Collector Books | |publisher = Collector Books | ||

| Line 337: | Line 220: | ||

| |location = Paducah, KY | |location = Paducah, KY | ||

| |pages = 311 | |pages = 311 | ||

| |url = | |||

| |oclc = | |||

| |isbn =978-1-57432-065-7 | |isbn =978-1-57432-065-7 | ||

| |ref=harv | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| Line 347: | Line 227: | ||

| |last2 = Seate | |last2 = Seate | ||

| |first2 =Emily | |first2 =Emily | ||

| |author-link = | |||

| |title = The Fostoria Value Guide | |title = The Fostoria Value Guide | ||

| |publisher = Collector Books | |publisher = Collector Books | ||

| Line 353: | Line 232: | ||

| |location = Paducah, KY | |location = Paducah, KY | ||

| |pages = 206 | |pages = 206 | ||

| |url = | |||

| |oclc = 229317585 | |oclc = 229317585 | ||

| |isbn =978-1-57432-583-6 | |isbn =978-1-57432-583-6 | ||

| |ref=harv | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| |last = Lucht | |last = Lucht | ||

| |first = Ralph K. | |first = Ralph K. | ||

| |author-link = | |||

| |title = Arnold Fiedler: Glass and Marble Maker Par Excellence | |title = Arnold Fiedler: Glass and Marble Maker Par Excellence | ||

| |publisher = AuthorHouse | |publisher = AuthorHouse | ||

| Line 367: | Line 243: | ||

| |location = Bloomington, IN | |location = Bloomington, IN | ||

| |pages = 27 | |pages = 27 | ||

| |url = | |||

| |oclc = 761194444 | |oclc = 761194444 | ||

| |isbn =978-1-456-73702-3 | |isbn =978-1-456-73702-3 | ||

| |ref=harv | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{Cite book | *{{Cite book | ||

| | last = McKelvey | | last = McKelvey | ||

| | first = Alexander T. | | first = Alexander T. | ||

| | last2 = | |||

| | first2 = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Centennial History of Belmont county, Ohio and Representative Citizens | | title = Centennial History of Belmont county, Ohio and Representative Citizens | ||

| | publisher = Biographical Publishing Company | | publisher = Biographical Publishing Company | ||

| | year = 1903 | | year = 1903 | ||

| | location = Chicago | | location = Chicago | ||

| | pages = | |||

| | pages = 833 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/centennialhistor00mcke | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/?id=idkyAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Centennial+history+of+belmont+county#v=onepage&q=Centennial%20history%20of%20belmont%20county&f=false | |||

| | quote = Centennial history of belmont county. | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | isbn = | |||

| | oclc = 318390043 | | oclc = 318390043 | ||

| |

}} | ||

| *{{Cite book | *{{Cite book | ||

| | last = Murray | | last = Murray | ||

| | first = Melvin L. | | first = Melvin L. | ||

| | last2 = | |||

| | first2 = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Fostoria, Ohio Glass II | | title = Fostoria, Ohio Glass II | ||

| | publisher = M. L. Murray | | publisher = M. L. Murray | ||

| Line 401: | Line 266: | ||

| | location = Fostoria, OH | | location = Fostoria, OH | ||

| | pages = 184 | | pages = 184 | ||

| | url = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | id = | |||

| | oclc = 27036061 | | oclc = 27036061 | ||

| |

}} | ||

| *{{Cite book | *{{Cite book | ||

| | last = Paquette | | last = Paquette | ||

| | first = Jack K. | | first = Jack K. | ||

| | |

| authorlink = Jack K. Paquette | ||

| | first2 = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s | | title = Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s | ||

| | publisher = Xlibris Corp. | | publisher = Xlibris Corp. | ||

| | year = 2002 | | year = 2002 | ||

| | location = | |||

| | pages = 559 | | pages = 559 | ||

| | url = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | isbn = 1-4010-4790-4 | | isbn = 1-4010-4790-4 | ||

| | oclc = 50932436 | | oclc = 50932436 | ||

| |

}} | ||

| *{{Cite book | *{{Cite book | ||

| | last = Prisant | | last = Prisant | ||

| | first = Carol | | first = Carol | ||

| | last2 = | |||

| | first2 = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Antiques Roadshow Collectibles: The Complete Guide to Collecting 20th Century Toys, Glassware, Costume Jewelry, Memorabilia, Ceramics, and More | | title = Antiques Roadshow Collectibles: The Complete Guide to Collecting 20th Century Toys, Glassware, Costume Jewelry, Memorabilia, Ceramics, and More | ||

| | publisher = Workman Publishing | | publisher = Workman Publishing | ||

| Line 435: | Line 287: | ||

| | location = New York | | location = New York | ||

| | pages = 589 | | pages = 589 | ||

| | url = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | isbn = 0-7611-2887-5 | | isbn = 0-7611-2887-5 | ||

| }} | |||

| | oclc = | |||

| |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{Cite book | *{{Cite book | ||