| Revision as of 04:26, 27 October 2010 edit202.169.20.134 (talk) →Definition← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:32, 5 December 2024 edit undoDrdr150 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users600 edits Undid revision 1261382161 by 58.96.56.87 (talk) good faithTag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Societal goal and normative concept}} | |||

| ]" NASA composite images: 2001 (left), 2002 (right).]] | |||

| {{Redirect-distinguish|Unsustainable|Unsustainable (song)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} | |||

| {{CS1 config|mode=cs1}} | |||

| '''Sustainability''' is a social goal for people to co-exist on ] over a long period of time. Definitions of this term are disputed and have varied with literature, context, and time.<ref name="Ramsey-2015">{{Cite journal |last=Ramsey |first=Jeffry L. |date=2015 |title=On Not Defining Sustainability |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3 |journal=Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics |language=en |volume=28 |issue=6 |pages=1075–1087 |doi=10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3 |bibcode=2015JAEE...28.1075R |issn=1187-7863 |s2cid=146790960}}</ref><ref name="Purvis" /> Sustainability usually has three dimensions (or pillars): environmental, economic, and social.<ref name="Purvis" /> Many definitions emphasize the environmental dimension.<ref name="Kotze-2022">{{cite book |last1=Kotzé |first1=Louis J. |date=2022 |title=The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals? |pages=140–171 |editor-last=Sénit |editor-first=Carole-Anne |place=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |doi=10.1017/9781009082945.007 |isbn=978-1-316-51429-0 |last2=Kim |first2=Rakhyun E. |last3=Burdon |first3=Peter |last4=du Toit |first4=Louise |last5=Glass |first5=Lisa-Maria |last6=Kashwan |first6=Prakash |last7=Liverman |first7=Diana |last8=Montesano |first8=Francesco S. |last9=Rantala |first9=Salla |chapter=Planetary Integrity |editor2-last=Biermann |editor2-first=Frank |editor3-last=Hickmann |editor3-first=Thomas |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Bosselmann-2010" /> This can include addressing key ], including ] and ]. The idea of sustainability can guide decisions at the global, national, organizational, and individual levels.<ref name="Berg-2020" /> A related concept is that of ], and the terms are often used to mean the same thing.<ref name="EB-2022">{{Cite news |title=Sustainability |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/sustainability |access-date=31 March 2022 |newspaper=Encyclopedia Britannica}}</ref> ] distinguishes the two like this: "''Sustainability'' is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while ''sustainable development'' refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it."<ref name="UNESCO-2015">{{Cite web |date=2015-08-03 |title=Sustainable Development |url=https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd/sd |access-date=20 January 2022 |website=UNESCO |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| '''Sustainability''' is the capacity to endure. In ], the word describes how biological systems remain ] and productive over time. Long-lived and healthy ] and ] are examples of sustainable biological systems. For humans, sustainability is the potential for long-term maintenance of well being, which has environmental, economic, and social dimensions. | |||

| Details around the economic dimension of sustainability are controversial.<ref name="Purvis" /> Scholars have discussed this under the concept of '']''. For example, there will always be tension between the ideas of "welfare and prosperity for all" and ],<ref name="Kuhlman-2010">{{Cite journal |last1=Kuhlman |first1=Tom |last2=Farrington |first2=John |date=2010 |title=What is Sustainability? |journal=Sustainability |language=en |volume=2 |issue=11 |pages=3436–3448 |doi=10.3390/su2113436 |issn=2071-1050 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Purvis" /> so ]s are necessary. It would be desirable to find ways that ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Nelson |first=Anitra |date=2024-01-31 |title=Degrowth as a Concept and Practice: Introduction |url=https://commonslibrary.org/degrowth-as-a-concept-and-practice-introduction/ |access-date=2024-02-23 |website=The Commons Social Change Library |language=en-AU}}</ref> This means using fewer resources per unit of output even while growing the economy.<ref name="UNEP2011" /> This decoupling reduces the environmental impact of economic growth, such as ]. Doing this is difficult.<ref name="Vaden-2020">{{Cite journal |last1=Vadén |first1=T. |last2=Lähde |first2=V. |last3=Majava |first3=A. |last4=Järvensivu |first4=P. |last5=Toivanen |first5=T. |last6=Hakala |first6=E. |last7=Eronen |first7=J.T. |date=2020 |title=Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature |journal=Environmental Science & Policy |language=en |volume=112 |pages=236–244 |bibcode=2020ESPol.112..236V |doi=10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.016 |pmc=7330600 |pmid=32834777}}</ref><ref name="Parrique T-2019" /> Some experts say there is no evidence that such a decoupling is happening at the required scale.<ref>Parrique, T., Barth, J., Briens, F., Kerschner, C., Kraus-Polk, A., Kuokkanen, A., & Spangenberg, J. H. (2019). Decoupling debunked. ''Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. A study edited by the European Environment Bureau EEB''.</ref> | |||

| Healthy ecosystems and environments provide vital goods and services to humans and other organisms. There are two major ways of reducing negative human impact and enhancing ]. The first is ]; this approach is based largely on information gained from ], ], and ]. The second approach is management of human ] of resources, which is based largely on information gained from ]. | |||

| It is challenging to ] as the concept is complex, contextual, and dynamic.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hardyment |first=Richard |title=Measuring Good Business: Making Sense of Environmental, Social & Governance Data |date=2024 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781032601199 |location=Abingdon}}</ref> Indicators have been developed to cover the environment, society, or the economy but there is no fixed definition of ''sustainability indicators''.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bell |first1=Simon |url=https://www.routledge.com/Sustainability-Indicators-Measuring-the-Immeasurable/Bell-Morse/p/book/9781844072996 |title=Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable? |last2=Morse |first2=Stephen |date=2012 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-84407-299-6 |location=Abington |publication-date=2012 |language=en}}</ref> The metrics are evolving and include ], benchmarks and audits. They include ] systems like ] and ]. They also involve indices and accounting systems such as corporate ] and ]. | |||

| Sustainability interfaces with economics through the social and ecological consequences of economic activity. Sustainability economics involves ecological economics where social, cultural, health-related and monetary/financial aspects are integrated. Moving towards sustainability is also a social challenge that entails ] and national ], ] and ], local and individual ] and ]. Ways of living more sustainably can take many forms from reorganising living conditions (e.g., ], ] and ]), reappraising economic sectors (], ], ]), or work practices (]), using science to develop new technologies (], ]), to adjustments in individual ] that conserve natural resources. | |||

| {{TOC limit|limit=3}} | |||

| It is necessary to address many barriers to sustainability to achieve a ''sustainability transition'' or ''sustainability transformation''.<ref name="Berg-2020" />{{rp|34}}<ref name="Howes-2017" /> Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity while others are ''extrinsic'' to the concept of sustainability. For example, they can result from the dominant institutional frameworks in countries. | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| Report of the IUCN Renowned Thinkers Meeting, 29–31 January 2006. Retrieved on: 2009-02-16.</ref>]] | |||

| Global issues of sustainability are difficult to tackle as they need global solutions. Existing global organizations such as the ] and ] are seen as inefficient in enforcing current global regulations. One reason for this is the lack of suitable ].<ref name="Berg-2020" />{{rp|135–145}} Governments are not the only sources of action for sustainability. For example, business groups have tried to integrate ecological concerns with economic activity, seeking ].<ref name="Kinsley-1997" /><ref name="Callenbach-2011" /> Religious leaders have stressed the need for caring for nature and environmental stability. Individuals can also ].<ref name="Berg-2020" /> | |||

| In: Ott, K. & P. Thapa (eds.) (2003).''Greifswald’s Environmental Ethics.'' Greifswald: Steinbecker Verlag Ulrich Rose. ISBN 3931483320. Retrieved on: 2009-02-16.</ref>]] | |||

| Some people have criticized the idea of sustainability. One point of criticism is that the concept is vague and only a ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Apetrei |first1=Cristina I. |last2=Caniglia |first2=Guido |last3=von Wehrden |first3=Henrik |last4=Lang |first4=Daniel J. |date=2021-05-01 |title=Just another buzzword? A systematic literature review of knowledge-related concepts in sustainability science |journal=Global Environmental Change |volume=68 |pages=102222 |doi=10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102222 |issn=0959-3780|doi-access=free |bibcode=2021GEC....6802222A }}</ref><ref name="Purvis" /> Another is that sustainability might be an impossible goal.<ref name="Melinda Harm">{{Cite journal |last1=Benson |first1=Melinda Harm |last2=Craig |first2=Robin Kundis |date=2014 |title=End of Sustainability |url=http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08941920.2014.901467 |journal=Society & Natural Resources |language=en |volume=27 |issue=7 |pages=777–782 |doi=10.1080/08941920.2014.901467 |bibcode=2014SNatR..27..777B |issn=0894-1920 |s2cid=67783261}}</ref> Some experts have pointed out that "no country is delivering what its citizens need without transgressing the biophysical planetary boundaries".<ref name="Stockholm+50-2022">{{Cite report |date=2022-05-18 |title=Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future |url=https://www.sei.org/publications/stockholm50-unlocking-better-future |work=Stockholm Environment Institute |doi=10.51414/sei2022.011 |s2cid=248881465|doi-access=free }}</ref>{{rp||page=11}} | |||

| The word sustainability is not derived from the Latin ''sustinere'' (''tenere'', to hold; ''sus'', up). Dictionaries provide more than ten meanings for ''sustain'', the main ones being to “maintain", "support", or "endure”.<ref></ref><ref>Onions, Charles, T. (ed) (1964). ''The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 2095.</ref> However, since the 1980s ''sustainability'' has been used more in the sense of human sustainability on planet Earth and this has resulted in the most widely quoted definition of sustainability and ], that of the ] of the ] on March 20, 1987: “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”<ref>United Nations General Assembly (1987) . Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 - Development and International Co-operation: Environment. Retrieved on: 2009-02-15.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-02.htm |title=''Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future''; Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 - Development and International Co-operation: Environment; Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development; Paragraph 1 |author=United Nations General Assembly |date=March 20, 1987 |work= |publisher=] |accessdate=1 March 2010}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

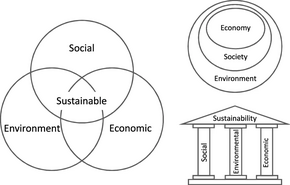

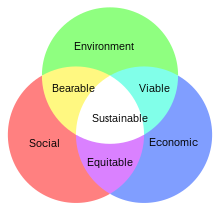

| At the ] it was noted that this requires the reconciliation of ], ] and ] demands - the "three pillars" of sustainability.<ref>] (2005). , Resolution A/60/1, adopted by the General Assembly on 15 September 2005. Retrieved on: 2009-02-17.</ref> This view has been expressed as an illustration using three overlapping ellipses indicating that the three pillars of sustainability are not mutually exclusive and can be mutually reinforcing.<ref>] of Great Britain. . Retrieved on: 2009-03-09</ref> | |||

| == Definitions == | |||

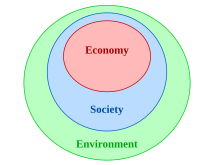

| The UN definition is not universally accepted and has undergone various interpretations.<ref>International Institute for Sustainable Development (2009). . Retrieved on: 2009-02-18.]</ref><ref>EurActiv (2004). Retrieved on: 2009-02-24</ref><ref>Kates, R., Parris, T. & Leiserowitz, A. (2005). ''Environment'' '''47(3)''': 8–21. Retrieved on: 2009-04-14.</ref> What sustainability is, what its goals should be, and how these goals are to be achieved is all open to interpretation.<ref>Holling, C. S. (2000). ''Conservation Ecology'' '''4(2)''': 7. Retrieved on: 2009-02-24.</ref> For many ]s the idea of sustainable development is an ] as development seems to entail environmental degradation.<ref>Redclift, M. (2005). "Sustainable Development (1987–2005): an Oxymoron Comes of Age." ''Sustainable Development'' '''13(4)''': 212–227.</ref> Ecological economist ] has asked, "what use is a sawmill without a forest?"<ref name="Daly & Cobb 1989">Daly & Cobb (1989).</ref> From this perspective, the economy is a subsystem of human society, which is itself a subsystem of the biosphere, and a gain in one sector is a loss from another.<ref>Porritt, J. (2006). ''Capitalism as if the world mattered''. London: Earthscan. p. 46. ISBN 9781844071937.</ref> This can be illustrated as three concentric circles. | |||

| === Current usage === | |||

| Sustainability is regarded as a "]".<ref name="Berg-2020" /><ref name="Scoones-2016">{{Cite journal |last=Scoones |first=Ian |date=2016 |title=The Politics of Sustainability and Development |journal=Annual Review of Environment and Resources |language=en |volume=41 |issue=1 |pages=293–319 |doi=10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090039 |issn=1543-5938 |s2cid=156534921|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Harrington-2016">{{Cite journal |last=Harrington |first=Lisa M. Butler |date=2016 |title=Sustainability Theory and Conceptual Considerations: A Review of Key Ideas for Sustainability, and the Rural Context |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309619897 |journal=Papers in Applied Geography |language=en |volume=2 |issue=4 |pages=365–382 |doi=10.1080/23754931.2016.1239222 |bibcode=2016PAGeo...2..365H |issn=2375-4931 |s2cid=132458202}}</ref><ref name="Ramsey-2015" /> This means it is based on what people value or find desirable: "The quest for sustainability involves connecting what is known through scientific study to applications in pursuit of what people want for the future."<ref name="Harrington-2016" /> | |||

| The 1983 UN Commission on Environment and Development (]) had a big influence on the use of the term ''sustainability'' today. The commission's 1987 Brundtland Report provided a definition of ]. The report, '']'', defines it as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of ] to meet their own needs".<ref name="UNGA-1987">United Nations General Assembly (1987) . Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment.</ref><ref name="UNGA-1987a">{{Cite web |last=United Nations General Assembly |date=20 March 1987 |title=''Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future''; Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment; Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development; Paragraph 1 |url=http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-02.htm |access-date=1 March 2010 |publisher=]}}</ref> The report helped bring ''sustainability'' into the mainstream of policy discussions. It also popularized the concept of ''sustainable development''.<ref name="Purvis">{{Cite journal |last1=Purvis |first1=Ben |last2=Mao |first2=Yong |last3=Robinson |first3=Darren |date=2019 |title=Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins |journal=Sustainability Science |language=en |volume=14 |issue=3 |pages=681–695 |doi=10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5 |bibcode=2019SuSc...14..681P |issn=1862-4065 |doi-access=free}} ] Text was copied from this source, which is available under a </ref> | |||

| A universally accepted definition of sustainability is elusive because it is expected to achieve many things. On the one hand it needs to be factual and scientific, a clear statement of a specific “destination”. The simple definition "sustainability is improving the quality of human life while living within the carrying capacity of supporting eco-systems",<ref name = caring>]/]/] (1991). Gland, Switzerland. Retrieved on: 2009-03-29.</ref> though vague, conveys the idea of sustainability having quantifiable limits. But sustainability is also a call to action, a task in progress or “journey” and therefore a political process, so some definitions set out common goals and values.</font><ref>Markus J., Milne M.K., Kearins, K., & Walton, S. (2006). ''Organization'' '''13(6)''': 801-839. Retrieved on 2009-09-23.</ref> The ]<ref name="EarthCharter">The Earth Charter Initiative (2000). Retrieved on: 2009-04-05.</ref> speaks of “a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace.” | |||

| Some other key concepts to illustrate the meaning of sustainability include:<ref name="Harrington-2016" /> | |||

| To add complication the word ''sustainability'' is applied not only to human sustainability on Earth, but to many situations and contexts over many scales of space and time, from small local ones to the global balance of production and consumption. It can also refer to a future intention: "sustainable agriculture" is not necessarily a current situation but a goal for the future, a prediction.<ref>Costanza, R. & Patten, B.C. (1995). "Defining and predicting sustainability." ''Ecological Economics''''' 15 (3)''': 193–196.</ref> For all these reasons sustainability is perceived, at one extreme, as nothing more than a feel-good ] with little meaning or substance<ref>Dunning, B. (2006). ''Skeptoid.'' Retrieved on: 2009-02-16.</ref><ref>Marshall, J.D. & Toffel, M.W. (2005). "Framing the Elusive Concept of Sustainability: A Sustainability Hierarchy." ''Environmental & Scientific Technology'' '''39(3)''': 673–682.</ref> but, at the other, as an important but unfocused concept like "liberty" or "justice".<ref>Blewitt, J. (2008). ''Understanding Sustainable Development''. London: Earthscan. pp. 21-24. ISBN 9781844074549.</ref> It has also been described as a "dialogue of values that defies consensual definition".<ref>Ratner, B.D. (2004). "Sustainability as a Dialogue of Values: Challenges to the Sociology of Development." ''Sociological Inquiry'' '''74(1)''': 50–69.</ref> | |||

| * It may be a ] but in a positive sense: the goals are more important than the approaches or means applied; | |||

| * It connects with other essential concepts such as resilience, ], and ]. | |||

| * Choices matter: "it is not possible to sustain everything, everywhere, forever"; | |||

| * Scale matters in both space and time, and place matters; | |||

| * Limits exist (see ]). | |||

| In everyday usage, ''sustainability'' often focuses on the environmental dimension.{{Citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|History of sustainability}} | |||

| ==== Specific definitions ==== | |||

| The history of sustainability traces human-dominated ] systems from the earliest ]s to the present. This history is characterized by the increased regional success of a particular ], followed by crises that were either resolved, producing sustainability, or not, leading to ].<ref>Beddoea, R., Costanzaa, R., Farleya, J., Garza, E., Kent, J., Kubiszewski, I., Martinez, L., McCowen, T., Murphy, K., Myers, N., Ogden, Z., Stapleton, K., and Woodward, J. (February 24, 2009). ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.'' '''106''' 8 2483–2489. Retrieved on: 2009-08-20.</ref><ref>] (2004). ''A Short History of Progress.'' Toronto: Anansi. ISBN 0887847064.</ref> | |||

| Scholars say that a single specific definition of sustainability may never be possible. But the concept is still useful.<ref name="Ramsey-2015" /><ref name="Harrington-2016" /> There have been attempts to define it, for example: | |||

| * "Sustainability can be defined as the capacity to maintain or improve the state and availability of desirable materials or conditions over the long term."<ref name="Harrington-2016" /> | |||

| * "Sustainability the long-term viability of a community, set of social institutions, or societal practice. In general, sustainability is understood as a form of intergenerational ethics in which the environmental and economic actions taken by present persons do not diminish the opportunities of future persons to enjoy similar levels of wealth, utility, or welfare."<ref name="EB-2022" /> | |||

| * "Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In addition to ], we also need social and economic resources. Sustainability is not just environmentalism. Embedded in most definitions of sustainability we also find concerns for social equity and economic development."<ref name="McGill-2022">{{Cite web |title=University of Alberta: What is sustainability? |url=https://www.mcgill.ca/sustainability/files/sustainability/what-is-sustainability.pdf |access-date=13 August 2022 |website=mcgill.ca}}</ref> | |||

| Some definitions focus on the environmental dimension. The '']'' defines sustainability as: "the property of being environmentally sustainable; the degree to which a process or enterprise is able to be maintained or continued while avoiding the long-term depletion of natural resources".<ref name="Halliday-2016">{{Cite web |last=Halliday |first=Mike |date=2016-11-21 |title=How sustainable is sustainability? |url=https://www.oxfordcollegeofprocurementandsupply.com/how-sustainable-is-sustainability/ |access-date=2022-07-12 |website=Oxford College of Procurement and Supply |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| In early human history, the use of fire and desire for specific foods may have altered the natural composition of plant and animal communities.<ref>Scholars, R. (2003). . Beyond Productions in association with S4C and S4C International. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved on: 2009-04-16.</ref> Between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago, ] communities emerged which depended largely on their ] and the creation of a "structure of permanence."<ref>Clarke, W. C. (1977). "The Structure of Permanence: The Relevance of Self-Subsistence Communities for World Ecosystem Management," in ''Subsistence and Survival: Rural Ecology in the Pacific.'' Bayliss-Smith, T. and R. Feachem (eds). London: Academic Press, pp. 363–384.</ref> | |||

| === Historical usage === | |||

| The Western ] of the 17th to 19th centuries tapped into the vast growth potential of the energy in ]. ] was used to power ever more efficient engines and later to generate electricity. Modern sanitation systems and advances in medicine protected large populations from disease.<ref>Hilgenkamp, K. (2005). . London: Jones & Bartlett. ISBN 9780763723774.</ref> In the mid-20th century, a gathering ] pointed out that there were environmental costs associated with the many material benefits that were now being enjoyed. In the late 20th century, environmental problems became global in scale.<ref>Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W. Behrens III. (1972). ''The Limits to Growth.'' New York: Universe Books. ISBN 0876631650.</ref><ref name=LPR>World Wide Fund for Nature (2008). . Retrieved on: 2009-03-29.</ref><ref>Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). World Resources Institute, Washington, DC. pp. 1-85. Retrieved on: 2009-07-08-01.</ref><ref>Turner, G.M. (2008). ''Global Environmental Change'' '''18''': 397–411. Online version published by CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems. Retrieved on: 2009-01-03</ref> The 1973 and 1979 ] demonstrated the extent to which the global community had become dependent on non-renewable energy resources. | |||

| {{Further|Sustainable development#Development of the concept}} | |||

| The term sustainability is derived from the ] word ''sustinere''. "To sustain" can mean to maintain, support, uphold, or endure.<ref>{{OEtymD|sustain}}</ref><ref>Onions, Charles, T. (ed) (1964). ''The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary''. Oxford: ]. p. 2095.</ref> So sustainability is the ability to continue over a long period of time. | |||

| In the past, sustainability referred to environmental sustainability. It meant using ]s so that people in the future could continue to rely on them in the long term.<ref name="WOR-2019">{{Cite web |title=Sustainability Theories |url=https://worldoceanreview.com/en/wor-4/concepts-for-a-better-world/what-is-sustainability/ |access-date=20 June 2019 |publisher=World Ocean Review}}</ref><ref name="OED-1835">Compare: {{oed|sustainability}} The English-language word had a legal technical sense from 1835 and a resource-management connotation from 1953.</ref> The concept of sustainability, or ''Nachhaltigkeit'' in German, goes back to ] (1645–1714), and applied to ]. The term for this now would be ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hans Carl von Carlowitz and Sustainability |url=http://www.environmentandsociety.org/tools/keywords/hans-carl-von-carlowitz-and-sustainability |access-date=20 June 2019 |website=Environment and Society Portal}}</ref> He used this term to mean the long-term responsible use of a natural resource. In his 1713 work ''Silvicultura oeconomica,''<ref>{{Cite web |last=Dresden |first=SLUB |title=Sylvicultura Oeconomica, Oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung Zur Wilden Baum-Zucht |url=http://digital.slub-dresden.de/id380451980/127 |access-date=2022-03-28 |website=digital.slub-dresden.de |language=de-DE}}</ref> he wrote that "the highest art/science/industriousness will consist in such a conservation and replanting of timber that there can be a continuous, ongoing and sustainable use".<ref>Von Carlowitz, H.C. & Rohr, V. (1732) Sylvicultura Oeconomica, oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung zur Wilden Baum Zucht, Leipzig; translated from German as cited in {{Cite journal |last1=Friederich |first1=Simon |last2=Symons |first2=Jonathan |date=2022-11-15 |title=Operationalising sustainability? Why sustainability fails as an investment criterion for safeguarding the future |journal=Global Policy |volume=14 |language=en |pages=1758–5899.13160 |doi=10.1111/1758-5899.13160 |issn=1758-5880 |s2cid=253560289|doi-access=free }}</ref> The shift in use of "sustainability" from preservation of forests (for future wood production) to broader preservation of environmental resources (to sustain the world for future generations) traces to a 1972 book by Ernst Basler, based on a series of lectures at M.I.T.<ref name="Basler-1972">{{cite book |last=Basler |first=Ernst |title= Strategy of Progress: Environmental Pollution, Habitat Scarcity and Future Research (originally, Strategie des Fortschritts: Umweltbelastung Lebensraumverknappung and Zukunftsforshung) |date=1972 |publisher= BLV Publishing Company}}</ref> | |||

| In the 21st century, there is increasing global awareness of the threat posed by the human-induced enhanced ], produced largely by forest clearing and the burning of fossil fuels.<ref>U.S. Department of Commerce. . NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory. Retrieved on: 2009-03-14</ref><ref>BBC News (August 2008). BBC News, UK. Retrieved on: 2009-03-14</ref> | |||

| The idea itself goes back a very long time: Communities have always worried about the capacity of their environment to sustain them in the long term. Many ancient cultures, ], and ] have restricted the use of natural resources.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Gadgil |first1=M. |last2=Berkes |first2=F. |date=1991 |title=Traditional Resource Management Systems |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248146028 |journal=Resource Management and Optimization |volume=8 |pages=127–141}}</ref> | |||

| ==Principles and concepts== | |||

| The philosophical and analytic framework of sustainability draws on and connects with many different disciplines and fields; in recent years an area that has come to be called ] has emerged. Sustainability science is not yet an autonomous field or discipline of its own, and has tended to be problem-driven and oriented towards guiding decision-making.<ref></ref> | |||

| === Comparison to sustainable development === | |||

| ===Scale and context=== | |||

| {{Further|Sustainable development}} | |||

| Sustainability is studied and managed over many scales (levels or frames of reference) of time and space and in many contexts of environmental, social and economic organization. The focus ranges from the total ] (sustainability) of planet Earth to the sustainability of economic sectors, ecosystems, countries, municipalities, neighbourhoods, home gardens, individual lives, individual goods and services, occupations, lifestyles, behaviour patterns and so on. In short, it can entail the full compass of biological and human activity or any part of it.<ref>Conceptual Framework Working Group of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2003). "Ecosystems and Human Well-being." London: Island Press. Chapter 5. "Dealing with Scale". pp. 107–124. ISBN 155634030.</ref> As Daniel Botkin, author and environmentalist, has stated: "We see a landscape that is always in flux, changing over many scales of time and space."<ref>Botkin (1990).</ref> | |||

| The terms sustainability and ] are closely related. In fact, they are often used to mean the same thing.<ref name="EB-2022" /> Both terms are linked with the "three dimensions of sustainability" concept.<ref name="Purvis" /> One distinction is that sustainability is a general concept, while sustainable development can be a policy or organizing principle. Scholars say sustainability is a broader concept because sustainable development focuses mainly on human well-being.<ref name="Harrington-2016" /> | |||

| ===Consumption — population, technology, resources=== | |||

| The overall driver of human impact on Earth systems is the destruction of ] ], and especially, the Earth's ecosystems. The total environmental impact of a community or of humankind as a whole depends both on population and impact per person, which in turn depends in complex ways on what resources are being used, whether or not those resources are renewable, and the scale of the human activity relative to the carrying capacity of the ecosystems involved. Careful resource management can be applied at many scales, from economic sectors like agriculture, manufacturing and industry, to work organizations, the consumption patterns of households and individuals and to the resource demands of individual goods and services.<ref>Clark (2006).</ref><ref name=Brower>Brower & Leon (1999).</ref> | |||

| Sustainable development has two linked goals. It aims to meet ] goals. It also aims to enable natural systems to provide the ]s and ] needed for ] and society. The concept of sustainable development has come to focus on ], ] and ] for future generations.{{Citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| One of the initial attempts to express human impact mathematically was developed in the 1970s and is called the ] formula. This formulation attempts to explain human consumption in terms of three components: ] numbers, levels of consumption (which it terms "affluence", although the usage is different), and impact per unit of resource use (which is termed "technology", because this impact depends on the ] used). The equation is expressed: | |||

| == Dimensions == | |||

| :::::::: I = P × A × T | |||

| === Development of three dimensions === | |||

| ], where sustainability is thought of as the area where the three dimensions overlap]] | |||

| Scholars usually distinguish three different areas of sustainability. These are the environmental, the social, and the economic. Several terms are in use for this concept. Authors may speak of three pillars, dimensions, components, aspects,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2005 |title=Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 16 September 2005, 60/1. 2005 World Summit Outcome |url=https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_60_1.pdf |access-date=17 January 2022 |publisher=United Nations General Assembly}}</ref> perspectives, factors, or goals. All mean the same thing in this context.<ref name="Purvis" /> The three dimensions paradigm has few theoretical foundations.<ref name="Purvis" /> | |||

| The popular three intersecting circles, or ], representing sustainability first appeared in a 1987 article by the economist ].<ref name="Purvis" /><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Barbier |first=Edward B. |date=July 1987 |title=The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/environmental-conservation/article/abs/concept-of-sustainable-economic-development/33A3CD3BD12DE8D5B2FF466701A14B4A |journal=Environmental Conservation |language=en |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=101–110 |bibcode=1987EnvCo..14..101B |doi=10.1017/S0376892900011449 |issn=1469-4387}}</ref> | |||

| ::: Where: I = Environmental impact, P = Population, A = Affluence, T = Technology<ref name=Ehrlich&Holden>Ehrlich, P.R. & Holden, J.P. (1974). "Human Population and the global environment." ''American Scientist'' '''62'''(3): 282–292.</ref> | |||

| Scholars rarely question the distinction itself. The idea of sustainability with three dimensions is a dominant interpretation in the literature.<ref name="Purvis" /> | |||

| ==Measurement== | |||

| {{Main|Sustainability measurement}} | |||

| Sustainability measurement is a term that denotes the measurements used as the quantitative basis for the informed management of sustainability.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.accaglobal.com/publicinterest/activities/research/reports/sustainable_and_transparent/rr-078 |title=Sustainability Accounting in UK Local Government |publisher=The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants |accessdate=2008-06-18}}</ref> The metrics used for the measurement of sustainability (involving the sustainability of environmental, social and economic domains, both individually and in various combinations) are still evolving: they include ]s, benchmarks, audits, indexes and accounting, as well as assessment, appraisal<ref>Dalal-Clayton, Barry and Sadler, Barry 2009. ''Sustainability Appraisal. A Sourcebook and Reference Guide to International Experience.'' London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-357-3.</ref> and other reporting systems. They are applied over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales.<ref>Hak, T. ''et al''. 2007. ''Sustainability Indicators'', SCOPE 67. Island Press, London.</ref><ref>Bell, Simon and Morse, Stephen 2008. ''Sustainability Indicators. Measuring the Immeasurable?'' 2nd edn. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6.</ref> | |||

| In the Brundtland Report, the environment and development are inseparable and go together in the search for sustainability. It described sustainable development as a global concept linking environmental and social issues. It added sustainable development is important for both ] and ]: | |||

| Some of the best known and most widely used sustainability measures include corporate ], ], and estimates of the quality of sustainability governance for individual countries using the ] and ]. | |||

| <noinclude>{{Blockquote | |||

| ===Population=== | |||

| | text =The 'environment' is where we all live; and 'development' is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable. We came to see that a new development path was required, one that sustained human progress not just in a few pieces for a few years, but for the entire planet into the distant future. Thus 'sustainable development' becomes a goal not just for the 'developing' nations, but for industrial ones as well. | |||

| {{Main|Population control|}} | |||

| | author ='']'' (also known as the Brundtland Report) | |||

| ] – ], illustrating current exponential growth]] | |||

| | title = | |||

| According to the 2008 Revision of the official United Nations population estimates and projections, the ] is projected to reach 7 billion early in 2012, up from the current 6.9 billion (May 2009), to exceed 9 billion people by 2050. Most of the increase will be in ] whose population is projected to rise from 5.6 billion in 2009 to 7.9 billion in 2050. This increase will be distributed among the population aged 15–59 (1.2 billion) and 60 or over (1.1 billion) because the number of children under age 15 in developing countries is predicted to decrease. In contrast, the population of the more ] is expected to undergo only slight increase from 1.23 billion to 1.28 billion, and this would have declined to 1.15 billion but for a projected net migration from developing to developed countries, which is expected to average 2.4 million persons annually from 2009 to 2050.<ref>United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2009). Highlights. Retrieved on: 2009-04-06.</ref> Long-term estimates of global population suggest a peak at around 2070 of nine to ten billion people, and then a slow decrease to 8.4 billion by 2100.<ref>Lutz ''et al''. (2004).</ref> | |||

| | source =<ref name="UNGA-1987" />{{rp|Foreword and Section I.1.10}} | |||

| | character = | |||

| | multiline = | |||

| | class = | |||

| | style = | |||

| }}</noinclude> | |||

| The ] from 1992 is seen as "the foundational instrument in the move towards sustainability".<ref name="Bosselmann-2022">Bosselmann, K. (2022) , Research Handbook on Fundamental Concepts of Environmental Law, edited by Douglas Fisher</ref>{{rp|29}} It includes specific references to ecosystem integrity.<ref name="Bosselmann-2022" />{{rp|31}} The plan associated with carrying out the Rio Declaration also discusses sustainability in this way. The plan, ], talks about economic, social, and environmental dimensions:<ref name="agenda 1">{{Cite web |date=1992 |title=Agenda 21 |url=https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf |access-date=17 January 2022 |publisher=United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992}}</ref>{{rp|8.6}} | |||

| Emerging economies like those of China and India aspire to the living standards of the Western world as does the non-industrialized world in general.<ref>"". BBC News. January 12, 2006.</ref> It is the combination of population increase in the developing world and unsustainable consumption levels in the developed world that poses a stark challenge to sustainability.<ref name=Cohen2006>Cohen, J.E. (2006). "Human Population: The Next Half Century." In Kennedy D. (Ed.) "Science Magazine's State of the Planet 2006-7". London: Island Press, pp. 13–21. ISSN 15591158.</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote | |||

| ===Carrying capacity=== | |||

| | text =Countries could develop systems for monitoring and evaluation of progress towards achieving sustainable development by adopting indicators that measure changes across economic, social and environmental dimensions. | |||

| {{See|Carrying capacity|}} | |||

| | author = ] | |||

| ] | |||

| | title = | |||

| More and more data are indicating that humans are not living within the ] of the planet. The ] measures human consumption in terms of the biologically productive land needed to provide the resources, and absorb the wastes of the average global citizen. In 2008 it required 2.7 ]s per person, 30% more than the natural biological capacity of 2.1 global hectares (assuming no provision for other organisms).<ref name="LPR"/> The resulting ecological deficit must be met from unsustainable ''extra'' sources and these are obtained in three ways: embedded in the goods and services of world trade; taken from the past (e.g. ]); or borrowed from the future as unsustainable resource usage (e.g. by ] ] and ]). | |||

| | source =<ref name="agenda 1" />{{rp|8.6}} | |||

| | character = | |||

| | multiline = | |||

| | class = | |||

| | style = | |||

| }} | |||

| Agenda 2030 from 2015 also viewed sustainability in this way. It sees the 17 ] (SDGs) with their 169 targets as balancing "the three dimensions of sustainable development, the economic, social and environmental".<ref name=":1b">United Nations (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, ] ( {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201128002202/https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/|date=28 November 2020}})</ref> | |||

| The figure (right) compares the sustainability of countries by contrasting their Ecological Footprint with their UN ] (a measure of standard of living). The graph shows what is necessary for countries to maintain an acceptable standard of living for their citizens while, at the same time, maintaining sustainable resource use. The general trend is for higher standards of living to become less sustainable. As always, ] has a marked influence on levels of consumption and the efficiency of resource use.<ref name="Ehrlich&Holden"/><ref>Adams & Jeanrenaud (2008) p. 45.</ref> The sustainability goal is to raise the global standard of living without increasing the use of resources beyond globally sustainable levels; that is, to not exceed "one planet" consumption. Information generated by reports at the national, regional and city scales confirm the global trend towards societies that are becoming less sustainable over time.<ref>UNEP Grid Arendal. A selection of global-scale reports. Retrieved on: 2009-3-12</ref><ref>Global Footprint Network. (2008). Retrieved on: 2008-10-01.</ref> | |||

| === Hierarchy === | |||

| ===Global human impact on biodiversity=== | |||

| ] and ] are constrained by ]<ref>Scott Cato, M. (2009). ''Green Economics''. London: ], pp. 36–37. {{ISBN|978-1-84407-571-3}}.</ref> ]]] is similar to the nested ellipses diagram, where the environmental dimension or system is the basis for the other two dimensions.<ref name="Obrecht-2021">{{Cite periodical |last1=Obrecht |first1=Andreas |last2=Pham-Truffert |first2=Myriam |last3=Spehn |first3=Eva |last4=Payne |first4=Davnah |last5=Altermatt |first5=Florian |last6=Fischer |first6=Manuel |last7=Passarello |first7=Cristian |last8=Moersberger |first8=Hannah |last9=Schelske |first9=Oliver |last10=Guntern |first10=Jodok |last11=Prescott |first11=Graham |date=2021-02-05 |title=Achieving the SDGs with Biodiversity |periodical=Swiss Academies Factsheet |volume=16 |issue=1 |language=en |doi=10.5281/zenodo.4457298 |doi-access=free}}</ref>]] | |||

| {{See|Millennium Ecosystem Assessment}} | |||

| Scholars have discussed how to rank the three dimensions of sustainability. Many publications state that the environmental dimension is the most important.<ref name="Kotze-2022" /><ref name="Bosselmann-2010">{{Cite journal |last=Bosselmann |first=Klaus |date=2010 |title=Losing the Forest for the Trees: Environmental Reductionism in the Law |journal=] |language=en |volume=2 |issue=8 |pages=2424–2448 |doi=10.3390/su2082424 |issn=2071-1050 |doi-access=free|hdl=10535/6499 |hdl-access=free }} ] Text was copied from this source, which is available under a </ref> (] or ecological integrity are other terms for the environmental dimension.) | |||

| At a fundamental level ] and ] set an upper limit on the number and mass of organisms in any ecosystem.<ref>Krebs (2001) p. 513.</ref> Human impacts on the Earth are demonstrated in a general way through detrimental changes in the global biogeochemical cycles of chemicals that are critical to life, most notably those of ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>Smil (2000)</ref> | |||

| Protecting ecological integrity is the core of sustainability according to many experts.<ref name="Bosselmann-2010" /> If this is the case then its environmental dimension sets limits to economic and social development.<ref name="Bosselmann-2010" /> | |||

| The ''Millennium Ecosystem Assessment'' is an international synthesis by over 1000 of the world's leading biological scientists that analyses the state of the Earth’s ]s and provides summaries and guidelines for decision-makers. It concludes that human activity is having a significant and escalating impact on the ] of world ], reducing both their ] and ]. The report refers to natural systems as humanity's "life-support system", providing essential "]". The assessment measures 24 ecosystem services concluding that only four have shown improvement over the last 50 years, 15 are in serious decline, and five are in a precarious condition.<ref>Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, pp. 6–19.</ref> | |||

| The diagram with three nested ellipses is one way of showing the three dimensions of sustainability together with a hierarchy: It gives the environmental dimension a special status. In this diagram, the environment includes society, and society includes economic conditions. Thus it stresses a hierarchy. | |||

| ==Environmental dimension== | |||

| Healthy ecosystems provide vital goods and services to humans and other organisms. There are two major ways of reducing negative human impact and enhancing ] and the first of these is ]. This direct approach is based largely on information gained from ], ] and ]. | |||

| However, this is management at the end of a long series of indirect causal factors that are initiated by human ], so a second approach is through demand management of human resource use. | |||

| Another model shows the three dimensions in a similar way: In this ''SDG wedding cake model'', the economy is a smaller subset of the societal system. And the societal system in turn is a smaller subset of the ] system.<ref name="Obrecht-2021" /> | |||

| Management of human ] of resources is an indirect approach based largely on information gained from ]. Herman Daly has suggested three broad criteria for ecological sustainability: renewable resources should provide a sustainable yield (the rate of harvest should not exceed the rate of regeneration); for non-renewable resources there should be equivalent development of renewable substitutes; waste generation should not exceed the assimilative capacity of the environment.<ref>Daly H.E. (1990). "Toward some operational principles of sustainable development." ''Ecological Economics '''''2''': 1–6.</ref> | |||

| In 2022 an assessment examined the political impacts of the Sustainable Development Goals. The assessment found that the "integrity of the earth's life-support systems" was essential for sustainability.<ref name="Kotze-2022" />{{rp|140}} The authors said that "the SDGs fail to recognize that planetary, people and prosperity concerns are all part of one earth system, and that the protection of planetary integrity should not be a means to an end, but an end in itself".<ref name="Kotze-2022" />{{rp|147}} The aspect of environmental protection is not an explicit priority for the SDGs. This causes problems as it could encourage countries to give the environment less weight in their developmental plans.<ref name="Kotze-2022" />{{rp|144}} The authors state that "sustainability on a planetary scale is only achievable under an overarching Planetary Integrity Goal that recognizes the biophysical limits of the planet".<ref name="Kotze-2022" />{{rp|161}} | |||

| ===Environmental management=== | |||

| {{Main|Sustainability and environmental management}} | |||

| At the global scale and in the broadest sense environmental management involves the ]s, ] systems, ] and ], but following the sustainability principle of scale it can be equally applied to any ecosystem from a tropical rainforest to a home garden.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.economics.noaa.gov/?goal=ecosystems&file=users/|title=The Economics and Social Benefits of NOAA Ecosystems Data and Products Table of Contents Data Users|publisher=NOAA|accessdate=2009-10-13}}</ref><ref>Buchenrieder, G., und A.R. Göltenboth: Sustainable freshwater resource management in the Tropics: The myth of effective indicators, 25th International Conference of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) on “Reshaping Agriculture’s Contributions to Society” in Durban, South Africa, 2003.</ref> | |||

| Other frameworks bypass the compartmentalization of sustainability into separate dimensions completely.<ref name="Purvis" /> | |||

| ====Atmosphere==== | |||

| In March 2009 at a meeting of the ], 2,500 climate experts from 80 countries issued a keynote statement that there is now "no excuse" for failing to act on global warming and that without strong carbon reduction targets "abrupt or irreversible" shifts in climate may occur that "will be very difficult for contemporary societies to cope with".<ref>University of Copenhagen (March 2009) News item on Copenhagen Climate Congress in March 2009. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref><ref>Adams, D. (March 2009) ''The Guardian''. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> Management of the global atmosphere now involves assessment of all aspects of the ] to identify opportunities to address human-induced ] and this has become a major focus of scientific research because of the potential catastrophic effects on biodiversity and human communities (see ] below). | |||

| === Environmental sustainability === | |||

| Other human impacts on the atmosphere include the ] in cities, the ] including toxic chemicals like ], ], ] and ] that produce ] and ], and the ]s that degrade the ]. ] ] such as sulphate ]s in the atmosphere reduce the direct ] and reflectance (]) of the ]'s surface. Known as ], the decrease is estimated to have been about 4% between 1960 and 1990 although the trend has subsequently reversed. Global dimming may have disturbed the global ] by reducing evaporation and rainfall in some areas. It also creates a ] effect and this may have partially masked the effect of ] on ].<ref>Hegerl, G.C. ''et al''. (2007). "Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis." Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. p. 676. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Full report at: IPCC Report. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> | |||

| {{Further|Human impact on the environment}} | |||

| The environmental dimension is central to the overall concept of sustainability. People became more and more aware of environmental pollution in the 1960s and 1970s. This led to discussions on sustainability and sustainable development. This process began in the 1970s with concern for environmental issues. These included natural ]s or natural resources and the human environment. It later extended to all systems that support life on Earth, including human society.<ref name="Swart, R.-2002">{{Cite book |author=Raskin, P. |author2=Banuri, T. |author3=Gallopín, G. |author4=Gutman, P. |author5=Hammond, A. |author6=Kates, R. |author7=Swart, R. |url=https://www.sei.org/publications/great-transition-promise-lure-times-ahead/ |title=Great transition: the promise and lure of the times ahead |date=2002 |publisher=Stockholm Environment Institute |isbn=0-9712418-1-3 |location=Boston |oclc=49987854}}</ref>{{rp|31}} Reducing these negative impacts on the environment would improve environmental sustainability.<ref name="Swart, R.-2002" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ekins |first1=Paul |last2=Zenghelis |first2=Dimitri |title=The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability |journal=Sustainability Science |date=2021 |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=949–965 |doi=10.1007/s11625-021-00910-5 |pmid=33747239 |pmc=7960882 |bibcode=2021SuSc...16..949E |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ] is not a new phenomenon. But it has been only a ''local'' or regional concern for most of human history. Awareness of ''global'' environmental issues increased in the 20th century.<ref name="Swart, R.-2002" />{{rp|5}}<ref>{{Cite book |title=Man's role in changing the face of the earth. |date=1956 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |editor=William L. Thomas |isbn=0-226-79604-3 |location=Chicago |oclc=276231}}</ref> The harmful effects and global spread of pesticides like ] came under scrutiny in the 1960s.<ref name="silentspring">{{Cite book |last=Carson, Rachel |url=https://archive.org/details/silentspring00cars_1 |title=Silent Spring |publisher=Mariner Books |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-618-24906-0 |orig-date=1st. Pub. Houghton Mifflin, 1962}}</ref> In the 1970s it emerged that ]s (CFCs) were depleting the ]. This led to the de facto ban of CFCs with the ] in 1987.<ref name="Berg-2020">{{Cite book |last=Berg |first=Christian |title=Sustainable action: overcoming the barriers |publisher=Routledge |date=2020 |isbn=978-0-429-57873-1 |location=Abingdon, Oxon |oclc=1124780147}}</ref>{{rp|146}} | |||

| ====Freshwater and Oceans==== | |||

| Water covers 71% of the Earth's surface. Of this, 97.5% is the salty water of the ]s and only 2.5% freshwater, most of which is locked up in the ]. The remaining freshwater is found in glaciers, lakes, rivers, wetlands, the soil, aquifers and atmosphere. Due to the water cycle, fresh water supply is continually replenished by precipitation, however there is still a limited amount necessitating management of this resource. Awareness of the global importance of preserving ] for ] has only recently emerged as, during the 20th century, more than half the world’s ] have been lost along with their valuable environmental services. Increasing ] pollutes clean water supplies and much of the world still does not have access to clean, safe ].<ref name="Atlas">Clarke & King (2006) pp. 20–21.</ref> Greater emphasis is now being placed on the improved management of blue (harvestable) and green (soil water available for plant use) water, and this applies at all scales of water management.<ref name="water">Hoekstra, A.Y. (2006). ''Value of Water Research Report Series'' No. 20 UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> | |||

| In the early 20th century, ] discussed the effect of ]es on the climate (see also: ]).<ref name="arrhenius">{{Cite journal |last=Arrhenius |first=Svante |date=1896 |title=XXXI. On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14786449608620846 |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |language=en |volume=41 |issue=251 |pages=237–276 |doi=10.1080/14786449608620846 |issn=1941-5982}}</ref> Climate change due to human activity became an academic and political topic several decades later. This led to the establishment of the ] in 1988 and the ] in 1992. | |||

| ] circulation patterns have a strong influence on ] and ] and, in turn, the food supply of both humans and other organisms. Scientists have warned of the possibility, under the influence of climate change, of a sudden alteration in circulation patterns of ]s that could drastically alter the climate in some regions of the globe.<ref>Kerr, R.A. (2004). "A slowing cog in the North Atlantic ocean's climate machine." ''Science'' '''304''': 371–372. Retrieved on: 2009-04-19.</ref> Ten per cent of the world's population – about 600 million people – live in low-lying areas vulnerable to sea level rise. | |||

| In 1972, the ] took place. It was the first UN conference on environmental issues. It stated it was important to protect and improve the human environment.<ref name="UN1973">UN (1973) , A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1, Stockholm, 5–16 June 1972</ref>{{rp|3}}It emphasized the need to protect wildlife and natural habitats:<ref name="UN1973" />{{rp|4}} | |||

| ====Land use==== | |||

| {{Blockquote | |||

| ] | |||

| | text =The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and natural ]s must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, as appropriate. | |||

| | author =] | |||

| | title = | |||

| | source =<ref name="UN1973" />{{rp|p.4., Principle 2}} | |||

| | character = | |||

| | multiline = | |||

| | class = | |||

| | style = | |||

| }} | |||

| In 2000, the UN launched eight ]. The aim was for the global community to achieve them by 2015. Goal 7 was to "ensure environmental sustainability". But this goal did not mention the concepts of social or economic sustainability.<ref name="Purvis" /> | |||

| Loss of biodiversity stems largely from the habitat loss and fragmentation produced by the human appropriation of land for development, forestry and agriculture as ] is progressively converted to man-made capital. Land use change is fundamental to the operations of the ] because alterations in the relative proportions of land dedicated to ], ], ], ], ] and ] have a marked effect on the global water, carbon and nitrogen ]s and this can impact negatively on both natural and human systems.<ref>Krebs (2001) pp. 560–582.</ref> At the local human scale, major sustainability benefits accrue from ] and ].<ref>, ''Missouri University Extension''. October 2004. Retrieved June 17, 2009.</ref><ref>, ''Daniel Boone Regional Library''. Retrieved June 17, 2009]</ref> | |||

| Specific problems often dominate public discussion of the environmental dimension of sustainability: In the 21st century these problems have included ], ] and pollution. Other global problems are loss of ]s, ], ] and ] and ], including ] and ].<ref name="UNEP-2021">{{Cite web |last=UNEP |date=2021 |title=Making Peace With Nature |url=http://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature |access-date=2022-03-30 |website=UNEP – UN Environment Programme |language=en}}</ref><ref name="Ripple-2017">{{Cite journal |last1=Ripple |first1=William J. |author-link1=William J. Ripple |last2=Wolf |first2=Christopher |last3=Newsome |first3=Thomas M. |last4=Galetti |first4=Mauro |last5=Alamgir |first5=Mohammed |last6=Crist |first6=Eileen |last7=Mahmoud |first7=Mahmoud I. |last8=Laurance |first8=William F. |last9=15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries |date=2017 |title=World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice |url=https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/67/12/1026/4605229 |journal=BioScience |language=en |volume=67 |issue=12 |pages=1026–1028 |doi=10.1093/biosci/bix125 |issn=0006-3568 |doi-access=free |hdl-access=free |hdl=11336/71342}}</ref> Many people worry about ]. These include impacts on the atmosphere, land, and ].<ref name="Swart, R.-2002" />{{rp|21}} | |||

| Since the Neolithic Revolution about 47% of the world’s forests have been lost to human use. Present-day forests occupy about a quarter of the world’s ice-free land with about half of these occurring in the tropics.<ref>World Resources Institute (1998). ''World Resources 1998–1999.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195214080.</ref> In temperate and boreal regions forest area is gradually increasing (with the exception of Siberia), but ] in the tropics is of major concern.<ref>Groombridge & Jenkins (2002).</ref> | |||

| Human activities now have an impact on Earth's ] and ]s. This led ] to call the current ] the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Crutzen |first=Paul J. |date=2002 |title=Geology of mankind |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=415 |issue=6867 |pages=23 |bibcode=2002Natur.415...23C |doi=10.1038/415023a |issn=0028-0836 |pmid=11780095 |s2cid=9743349|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ] is essential to life and feeding more than six billion human bodies takes a heavy toll on the Earth’s resources. This begins with the appropriation of about 38% of the Earth’s land surface<ref>Food and Agriculture Organization (June 2006). Rome: FAO Statistics Division. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> and about 20% of its net primary productivity.<ref>Imhoff, M.L. ''et al''. (2004). "Global Patterns in Human Consumption of Net Primary Production." ''Nature'' '''429''': 870–873.</ref> Added to this are the resource-hungry activities of industrial agribusiness – everything from the crop need for irrigation water, synthetic ]s and ]s to the resource costs of food packaging, ] (now a major part of global trade) and retail. Environmental problems associated with ] and ] are now being addressed through such movements as ], ] and more sustainable business practices.<ref> This web site has multiple articles on ] contributions to sustainable development. Retrieved on: 2009-04-07.</ref> | |||

| === Economic sustainability === | |||

| ===Management of human consumption=== | |||

| ] can improve aspects of economic sustainability (left: the 'take, make, waste' linear approach; right: the circular economy approach).]] | |||

| {{See|Consumption (economics)}} | |||

| The economic dimension of sustainability is controversial.<ref name="Purvis" /> This is because the term ''development'' within ''sustainable development'' can be interpreted in different ways. Some may take it to mean only ] and ]. This can promote an economic system that is bad for the environment.<ref name="Wilhelm-2000">{{Cite book |title=Zukunftsstreit |publisher=Velbrück Wissenschaft |editor=Wilhelm Krull |year=2000 |isbn=3-934730-17-5 |location=Weilerwist |language=de |oclc=52639118}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Redclift |first=Michael |date=2005 |title=Sustainable development (1987-2005): an oxymoron comes of age |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sd.281 |journal=Sustainable Development |language=en |volume=13 |issue=4 |pages=212–227 |doi=10.1002/sd.281 |issn=0968-0802}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Daly |first=Herman E. |url=http://pinguet.free.fr/daly1996.pdf |title=Beyond growth: the economics of sustainable development |date=1996 |publisher=] |isbn=0-8070-4708-2 |location=Boston |oclc=33946953}}</ref> Others focus more on the trade-offs between ] and achieving welfare goals for ] (food, water, health, and shelter).<ref name="Kuhlman-2010" /> | |||

| ] of manufacturing]] | |||

| The underlying driver of direct human impacts on the environment is human consumption.<ref>Michaelis, L. & Lorek, S. (2004). “Consumption and the Environment in Europe: Trends and Futures.” Danish Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Project No. 904. </ref> This impact is reduced by not only consuming less but by also making the full cycle of production, use and disposal more sustainable. Consumption of goods and services can be analysed and managed at all scales through the chain of consumption, starting with the effects of individual lifestyle choices and spending patterns, through to the resource demands of specific goods and services, the impacts of economic sectors, through national economies to the global economy.<ref>Jackson, T. & Michaelis, L. (2003). "Policies for Sustainable Consumption". The UK Sustainable Development Commission. </ref> Analysis of consumption patterns relates resource use to the environmental, social and economic impacts at the scale or context under investigation. The ideas of ] resource use (the total resources needed to produce a product or service), ], and ] are important tools for understanding the impacts of consumption. Key resource categories relating to human needs are ], ], ]s and ]. | |||

| Economic development can indeed reduce ] or ]. This is especially the case in the ]. That is why ] calls for economic growth to drive social progress and well-being. Its first target is for: "at least 7 per cent ] growth per annum in the least developed countries".<ref name="UN-2017">United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, ] ()</ref> However, the challenge is to expand economic activities while reducing their environmental impact.<ref name="UNEP2011">UNEP (2011) . Fischer-Kowalski, M., Swilling, M., von Weizsäcker, E.U., Ren, Y., Moriguchi, Y., Crane, W., Krausmann, F., Eisenmenger, N., Giljum, S., Hennicke, P., Romero Lankao, P., Siriban Manalang, A., Sewerin, S.</ref>{{rp|8}} In other words, humanity will have to find ways how societal progress (potentially by economic development) can be reached without excess strain on the environment. | |||

| ====Energy==== | |||

| {{Main|Sustainable energy|Renewable energy|Efficient energy use}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The Sun's energy, stored by plants (]s) during ], passes through the food chain to other organisms to ultimately power all living processes. Since the ] the concentrated energy of the ] stored in fossilized plants as ]s has been a major driver of ] which, in turn, has been the source of both economic and political power. In 2007 climate scientists of the ] concluded that there was at least a 90% probability that atmospheric increase in CO<sub>2</sub> was human-induced, mostly as a result of fossil fuel emissions but, to a lesser extent from changes in land use. Stabilizing the world’s climate will require high-income countries to reduce their emissions by 60–90% over 2006 levels by 2050 which should hold CO<sub>2</sub> levels at 450–650 ppm from current levels of about 380 ppm. Above this level, temperatures could rise by more than 2°C to produce “catastrophic” ].<ref>IPCC (2007). Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref><ref>UNFCC (2009). Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> Reduction of current CO<sub>2</sub> levels must be achieved against a background of global population increase and developing countries aspiring to energy-intensive high consumption Western lifestyles.<ref>Goodall (2007).</ref> | |||

| The Brundtland report says ] ''causes'' environmental problems. Poverty also ''results'' from them. So addressing environmental problems requires understanding the factors behind world poverty and inequality.<ref name="UNGA-1987" />{{rp|Section I.1.8}} The report demands a new development path for sustained human progress. It highlights that this is a goal for both developing and industrialized nations.<ref name="UNGA-1987" />{{rp|Section I.1.10}} | |||

| Reducing greenhouse emissions, referred to as ], is being tackled at all scales, ranging from tracking the passage of carbon through the ]<ref>U.S. Department of NOAA Research. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> to the ], developing less carbon-hungry technology and transport systems and attempts by individuals to lead ] lifestyles by monitoring the fossil fuel use embodied in all the goods and services they use.<ref>Fujixerox One of many carbon calculators readily accessible on the web. Retrieved on: 2009-04-07.</ref> | |||

| UNEP and ] launched the Poverty-Environment Initiative in 2005 which has three goals. These are reducing extreme poverty, greenhouse gas emissions, and net natural asset loss. This guide to structural reform will enable countries to achieve the SDGs.<ref>{{Cite web |title=UN Environment {{!}} UNDP-UN Environment Poverty-Environment Initiative |url=https://www.unpei.org/ |access-date=2022-01-24 |website=UN Environment {{!}} UNDP-UN Environment Poverty-Environment Initiative |language=en}}</ref><ref>PEP (2016) </ref>{{rp|11}} It should also show how to address the trade-offs between ] and economic development.<ref name="Berg-2020" />{{rp|82}} | |||

| ====Water==== | |||

| {{See|Water resources}} | |||

| === Social sustainability === | |||

| ] and ] are inextricably linked. In the decade 1951–60 human water withdrawals were four times greater than the previous decade. This rapid increase resulted from scientific and technological developments impacting through the ] – especially the increase in irrigated land, growth in industrial and power sectors, and intensive ] construction on all continents. This altered the ] of ]s and ]s, affected their ] and had a significant impact on the ].<ref name="Shik" /> Currently towards 35% of human water use is unsustainable, drawing on diminishing aquifers and reducing the flows of major rivers: this percentage is likely to increase if ] impacts become more severe, ]s increase, aquifers become progressively depleted and supplies become polluted and unsanitary.<ref>Clarke & King (2006) pp. 22–23.</ref> From 1961 to 2001 water demand doubled - agricultural use increased by 75%, industrial use by more than 200%, and domestic use more than 400%.<ref>Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, pp. 51–53.</ref> In the 1990s it was estimated that humans were using 40–50% of the globally available freshwater in the approximate proportion of 70% for ], 22% for ], and 8% for domestic purposes with total use progressively increasing.<ref name="Shik">Shiklamov, I. (1998). "World Water Resources. A New Appraisal and Assessment for the 21st century." A Summary of the Monograph World Water Resources prepared in the Framework of the International Hydrological Programme. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> | |||

| ] is just one part of social sustainability.]] | |||

| The social dimension of sustainability is not well defined.<ref name="Peterson">{{Cite journal |last1=Boyer |first1=Robert H. W. |last2=Peterson |first2=Nicole D. |last3=Arora |first3=Poonam |last4=Caldwell |first4=Kevin |date=2016 |title=Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward |journal=Sustainability |language=en |volume=8 |issue=9 |pages=878 |doi=10.3390/su8090878 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Dogu-2019">{{Cite journal |last1=Doğu |first1=Feriha Urfalı |last2=Aras |first2=Lerzan |date=2019 |title=Measuring Social Sustainability with the Developed MCSA Model: Güzelyurt Case |journal=] |language=en |volume=11 |issue=9 |pages=2503 |doi=10.3390/su11092503 |issn=2071-1050 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Davidson |first=Mark |date=2010 |title=Social Sustainability and the City: Social sustainability and city |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00339.x |journal=] |language=en |volume=4 |issue=7 |pages=872–880 |doi=10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00339.x}}</ref> One definition states that a society is sustainable in social terms if people do not face structural obstacles in key areas. These key areas are health, influence, competence, ] and ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Missimer |first1=Merlina |last2=Robèrt |first2=Karl-Henrik |last3=Broman |first3=Göran |date=2017 |title=A strategic approach to social sustainability – Part 2: a principle-based definition |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959652616303274 |journal=Journal of Cleaner Production |language=en |volume=140 |pages=42–52 |doi=10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.059|bibcode=2017JCPro.140...42M }}</ref> | |||

| Some scholars place social issues at the very center of discussions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Boyer |first1=Robert |last2=Peterson |first2=Nicole |last3=Arora |first3=Poonam |last4=Caldwell |first4=Kevin |date=2016 |title=Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward |journal=] |language=en |volume=8 |issue=9 |pages=878 |doi=10.3390/su8090878 |issn=2071-1050 |doi-access=free}}</ref> They suggest that all the domains of sustainability are social. These include ], economic, political, and cultural sustainability. These domains all depend on the relationship between the social and the natural. The ecological domain is defined as human embeddedness in the environment. From this perspective, social sustainability encompasses all human activities.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=James |first1=Paul |url=https://www.academia.edu/9294719 |title=Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability |last2=with Magee |first2=Liam |last3=Scerri |first3=Andy |last4=Steger |first4=Manfred B. |publisher=] |year=2015 |isbn=9781315765747 |location=London |author1-link=Paul James (academic)}}</ref> It goes beyond the intersection of economics, the environment, and the social.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Liam Magee |last2=Andy Scerri |last3=Paul James |last4=James A. Thom |last5=Lin Padgham |last6=Sarah Hickmott |last7=Hepu Deng |last8=Felicity Cahill |year=2013 |title=Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach |url=https://www.academia.edu/4362669 |journal=] |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=225–243 |doi=10.1007/s10668-012-9384-2 |bibcode=2013EDSus..15..225M |s2cid=153452740}}</ref> | |||

| Water efficiency is being improved on a global scale by increased ], improved infrastructure, improved water ] of agriculture, minimising the water intensity (embodied water) of goods and services, addressing shortages in the non-industrialised world, concentrating food production in areas of high productivity, and planning for ]. At the local level, people are becoming more self-sufficient by harvesting rainwater and reducing use of mains water.<ref name="water" /><ref>Hoekstra, A.Y. & Chapagain, A.K. (2007). "The Water Footprints of Nations: Water Use by People as a Function of their Consumption Pattern." ''Water Resource Management'' '''21(1)''': 35–48.</ref> | |||

| There are many broad strategies for more sustainable social systems. They include improved education and the political ]. This is especially the case in developing countries. They include greater regard for ]. This involves equity between rich and poor both within and between countries. And it includes ].<ref name="Cohen2006">{{cite book |last=Cohen |first=J. E. |date=2006 |chapter=Human Population: The Next Half Century. |editor-last=Kennedy |editor-first=D. |title=Science Magazine's State of the Planet 2006-7 |location=London |publisher=] |pages=13–21 |isbn=9781597266246}}</ref> Providing more ]s to ] would contribute to social sustainability.<ref name="Aggarwal-2022" />{{rp|11}} | |||

| ====Food==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{See|Food|Food security}} | |||

| A society with a high degree of social sustainability would lead to livable communities with a good ] (being fair, diverse, connected and democratic).<ref>{{Cite web |date=2012 |title=The Regional Institute – WACOSS Housing and Sustainable Communities Indicators Project |url=http://www.regional.org.au/au/soc/2002/4/barron_gauntlett.htm |access-date=2022-01-26 |website=www.regional.org.au}}</ref> | |||

| The ] (APHA) defines a "sustainable food system"<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Feenstra |first=G. |year=2002 |title=Creating Space for Sustainable Food Systems: Lessons from the Field |journal=Agriculture and Human Values |volume='''19 '''|issue='''2''' |pages=99–106 |doi=10.1023/A:1016095421310}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Harmon A.H., Gerald B.L.|year=2007 |month=June, |title=Position of the American Dietetic Association: Food and Nutrition Professionals Can Implement Practices to Conserve Natural Resources and Support Ecological Sustainabiility |journal=Journal of the American Dietetic Association |volume='''107 '''|issue='''6''' |pages=1033–43. |pmid=17571455 |url=http://www.eatright.org/ada/files/Conservenp.pdf |format=PDF|doi=10.1016/j.jada.2007.05.138}} Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> as "one that provides healthy food to meet current food needs while maintaining healthy ecosystems that can also provide food for generations to come with minimal negative impact to the environment. A sustainable food system also encourages local production and distribution infrastructures and makes nutritious food available, accessible, and affordable to all. Further, it is humane and just, protecting farmers and other workers, consumers, and communities."<ref>{{Cite web|publisher=American Public Health Association |date=2007-06-11 |title=Toward a Healthy, Sustainable Food System (Policy Number: 200712) |url=http://www.apha.org/advocacy/policy/policysearch/default.htm?id=1361 |accessdate=: 2008-08-18}}</ref> Concerns about the environmental impacts of ] and the stark contrast between the ] problems of the Western world and the poverty and food insecurity of the developing world have generated a strong movement towards healthy, sustainable eating as a major component of overall ].<ref>Mason & Singer (2006).</ref> The environmental effects of different dietary patterns depend on many factors, including the proportion of animal and plant foods consumed and the method of food production.<ref>{{Cite journal|author=McMichael A.J., Powles J.W., Butler C.D., Uauy R. |title=Food, Livestock Production, Energy, Climate change, and Health. |journal=Lancet |year=September 2007 |pmid=17868818 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61256-2 |url=http://www.eurekalert.org/images/release_graphics/pdf/EH5.pdf |format=PDF|volume=370 |page=1253 |issue=9594}} Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Baroni L., Cenci L., Tettamanti M., Berati M. |title=Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Various Dietary Patterns Combined with Different Food Production Systems.|journal=Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. |year=February 2007 |volume='''61''' |issue='''2 '''|pages=279–86 |pmid=17035955 |doi=10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602522 |url=http://www-personal.umich.edu/~choucc/environmental_impact_of_various_dietary_patterns.pdf|format=PDF}} Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref><ref>Steinfeld H., Gerber P., Wassenaar T., Castel V., Rosales M., de Haan, C. (2006). 390 pp. Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Heitschmidt R.K., Vermeire L.T., Grings E.E. |title=Is Rangeland Agriculture Sustainable? |journal=Journal of Animal Science. |year=2004 |volume=82|issue=E-Suppl |pages=E138–146 |pmid=15471792 |doi= |url=}} Retrieved on: 2009-03-18.</ref> The ] has published a ''Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health'' report which was endorsed by the May 2004 ]. It recommends the Mediterranean diet which is associated with health and ] and is low in ], rich in ]s and ]s, low in added sugar and limited salt, and low in ]ty acids; the traditional source of ] in the Mediterranean is ], rich in ]. The healthy rice-based Japanese diet is also high in ]s and low in fat. Both diets are low in meat and ]s and high in ]s and other vegetables; they are associated with a low incidence of ailments and low environmental impact.<ref>World Health Organisation (2004). Copy of the strategy endorsed by the World Health Assembly. Retrieved on: 2009-6-19.</ref> | |||

| ] might have a focus on particular aspects of sustainability, for example spiritual aspects, community-based governance and an emphasis on place and locality.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Virtanen |first1=Pirjo Kristiina |last2=Siragusa |first2=Laura |last3=Guttorm |first3=Hanna |date=2020 |title=Introduction: toward more inclusive definitions of sustainability |journal=Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability |language=en |volume=43 |pages=77–82 |doi=10.1016/j.cosust.2020.04.003|bibcode=2020COES...43...77V |s2cid=219663803 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||