| Revision as of 22:19, 12 February 2006 editTigerShark (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators17,615 edits rv to Tsca.bot← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:24, 15 December 2024 edit undoHudecEmil (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,903 edits →See also: Satiety value | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Chemical energy animals derive from food}} | |||

| '''Food energy''' is the amount of ] in food that is available through ]. The values for food energy are expressed in kilocalories (kcal) and kilojoules (kJ). | |||

| {{Use British English Oxford spelling|date=December 2019}} | |||

| '''Food energy''' is ] that animals (including ]s) derive from their ] to sustain their ], including their ] activity.<ref name=marsh2020/> | |||

| Most animals derive most of their energy from ], namely combining the ]s, ]s, and ]s with ] from ] or dissolved in ].<ref name=ross2000/> Other smaller components of the diet, such as ]s, ]s, and ] (drinking alcohol) may contribute to the energy input. Some ] components that provide little or no food energy, such as ], ], ]s, ], and ], may still be necessary to health and survival for other reasons. Some organisms have instead ], which extracts energy from food by reactions that do not require oxygen. | |||

| One ] is the amount of energy (heat) to raise the temperature of one gram of water one degree Celsius. The magnitude of human energy requirements makes it awkward to use such a small unit, so the convention of the capitalized Calorie is equal to 1000 lowercase calories, and is abbreviated kcal to indicate that is 1000 times as large as the calorie. | |||

| The energy contents of a given mass of food is usually expressed in the ] unit of energy, the ] (J), and its multiple the ] (kJ); or in the traditional unit of heat energy, the ] (cal). In nutritional contexts, the latter is often (especially in US) the "large" variant of the unit, also written "Calorie" (with symbol Cal, both with capital "C") or "kilocalorie" (kcal), and equivalent to 4184 J or 4.184 kJ.<ref name=FAO2003/> Thus, for example, fats and ethanol have the greatest amount of food energy per unit mass, {{convert|37|and|29|kJ/g|kcal/g|0|abbr=on}}, respectively. Proteins and most carbohydrates have about {{convert|17|kJ/g|kcal/g|abbr=on|0}}, though there are differences between different kinds. For example, the values for glucose, sucrose, and starch are {{convert|15.57|,|16.48|and|17.48|kJ/g|kcal/g}} respectively. The differing ] of foods (fat, alcohols, carbohydrates and proteins) lies mainly in their varying proportions of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. Carbohydrates that are not easily absorbed, such as fibre, or ] in ], contribute less food energy. ]s (including ]s) and organic acids contribute {{convert|10|kJ/g|kcal/g|abbr=on}} and {{convert|13|kJ/g|kcal/g|abbr=on}} respectively.<ref name="uk">{{cite web |title=Schedule 7: Nutrition labelling |url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1996/1499/schedule/7/made |website=Legislation.gov.uk |publisher=The National Archives |access-date=13 December 2019 |date=1 July 1996}}</ref> | |||

| The ] unit ] is becoming more common. In some countries (Australia, for example) only the kilojoule is normally used. Some types of food contain more food energy than others: ]s and ]s have particularly high values for food energy. One ] is approximately equal to 4.1868 kilojoules. | |||

| The energy contents of a complex dish or meal can be approximated by adding the energy contents of its components. | |||

| ==Measuring food energy== | |||

| In the early twentieth century, the United States Department of Agriculture (]) developed a procedure for measuring food energy that remains in use today. | |||

| == History and methods of measurement == | |||

| The food being measured is completely burned in a ] so that the ] released through ] can be accurately measured. This amount is used to determine the '''gross energy value''' of the particular food. This number is then multiplied by a ] which is based on how the human body actually digests the food. | |||

| ===Direct calorimetry of combustion=== | |||

| For example, pure sugar releases about 3.95 kilocalories per gram (16.5 kJ/g) of ''gross energy'' but the digestibility coefficient of sugar is about 98% in humans, so the ''food energy'' of sugar is 0.98 × 3.95 = 3.87 kilocalories per gram (16.2 kJ/g) of sugar. | |||

| The first determinations of the energy content of food were made by burning a dried sample in a ] and measuring the temperature change in the water surrounding the apparatus, a method known as direct ].<ref name=youd2021/> | |||

| == Energy content == | |||

| ===The Atwater system=== | |||

| * ''']''' contains about '''4''' nutritional calories per gram (17 kJ/g) | |||

| {{main|Atwater system}} | |||

| * ''']''' contains about '''4''' nutritional calories per gram (17 kJ/g) | |||

| * ''']''' contains about '''9''' nutritional calories per gram (38 kJ/g) | |||

| * ''']''' contains about '''7 ''' nutritional calories per gram (29 kJ/g) | |||

| However, the direct calorimetric method generally overestimates the actual energy that the body can obtain from the food, because it also counts the energy contents of ] and other indigestible components, and does not allow for partial absorption and/or incomplete metabolism of certain substances. For this reason, today the energy content of food is instead obtained indirectly, by using chemical analysis to determine the amount of each digestible dietary component (such as protein, carbohydrates, and fats), and adding the respective food energy contents, previously obtained by measurement of metabolic heat released by the body.<ref name=CANH1997/><ref name=SciAm/> In particular, the fibre content is excluded. This method is known as the ] system, after ] who pioneered these measurements in the late 19th century.<ref name=marsh2020/><ref name=triv2009/> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| The system was later improved by ] and ] of the ], who derived a system whereby specific calorie conversion factors for different foods were proposed.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Annabel Merrill|author2=Bernice Watt|title=Energy Values of Food ... basis and derivation|date=1973|publisher=United States Department of Agriculture|url=https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400525/Data/Classics/ah74.pdf|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161122060858/https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400525/Data/Classics/ah74.pdf|archivedate=22 November 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| == Dietary sources of energy == | |||

| The typical human ] consists chiefly of carbohydrates, fats, proteins, water, ethanol, and indigestible components such as ]s, ]s, and fibre (mostly ]). Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins typically comprise ninety percent of the dry weight of food.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.merck.com/mmhe/sec12/ch152/ch152b.html |title=Carbohydrates, Proteins, Nutrition|work= The Merck Manual}}</ref> ]s can extract food energy from the respiration of cellulose because of ] in their ]s that decompose it into digestible carbohydrates. | |||

| Other minor components of the human diet that contribute to its energy content are organic acids such as ] and ], and polyols such as ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| Some nutrients have regulatory roles affected by ], in addition to providing energy for the body.<ref name=jeff2006/> For example, ] plays an important role in the regulation of protein metabolism and suppresses an individual's appetite.<ref name=garl2005/> Small amounts of ], constituents of some fats that cannot be synthesized by the human body, are used (and necessary) for other biochemical processes. | |||

| The approximate food energy contents of various human diet components, to be used in package labeling according to the EU regulations<ref name=EUtab1990/> and UK regulations,<ref name=UKSI1996/> are: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan=2 | Food component | |||

| ! colspan=2 | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! kJ/g | |||

| ! kcal/g | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | align=center|37 | |||

| | align=center|9 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | align=center|29 | |||

| | align=center|7 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]s | |||

| | align=center|17 | |||

| | align=center|4 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]s | |||

| | align=center|17 | |||

| | align=center|4 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]s | |||

| | align=center|13 | |||

| | align=center|3 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]s (]s, ]) (1) | |||

| | align=center|10 | |||

| | align=center|2.4 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (2) | |||

| | align=center|8 | |||

| | align=center|2 | |||

| |} | |||

| (1) Some polyols, like ], are not digested and should be excluded from the count. | |||

| (2) This entry exists in the EU regulations of 2008,<ref name=EUtab1990/> but not in the UK regulations, according to which fibre shall not be counted.<ref name=UKSI1996/> | |||

| More detailed tables for specific foods have been published by many organizations, such as the ] also has published a similar table.<ref name=FAO2003/> | |||

| Other components of the human diet are either noncaloric, or are usually consumed in such small amounts that they can be neglected. | |||

| == Energy usage in the human body == | |||

| {{Main article|Bioenergetics|Energy balance (biology)}} | |||

| The food energy actually obtained by respiration is used by the human body for a wide range of purposes, including ] of various organs and tissues, maintaining the internal ], and exerting ] force to maintain posture and produce motion. About 20% is used for brain metabolism.<ref name=FAO2003/> | |||

| The conversion efficiency of energy from respiration into muscular (physical) ] depends on the type of food and on the type of physical energy usage (e.g., which muscles are used, whether the muscle is used ] or ]). In general, the efficiency of muscles is rather low: only 18 to 26% of the energy available from respiration is converted into mechanical energy.<ref name="seiler"/> This low efficiency is the result of about 40% efficiency of generating ] from the respiration of food, losses in converting energy from ATP into mechanical work inside the muscle, and mechanical losses inside the body. The latter two losses are dependent on the type of exercise and the type of muscle fibers being used (fast-twitch or slow-twitch). For an overall efficiency of 20%, one watt of mechanical power is equivalent to {{convert|4.3|kcal/h|kJ/h|order=flip|abbr=on}}. For example, a manufacturer of rowing equipment shows calories released from "burning" food as four times the actual mechanical work, plus {{convert|300|kcal|kJ|abbr=on|order=flip}} per hour,<ref name=concept2/> which amounts to about 20% efficiency at 250 watts of mechanical output. It can take up to 20 hours of little physical output (e.g., walking) to "burn off" {{convert|4000|kcal|kJ|abbr=on|order=flip}}<ref name=guyt2006/> more than a body would otherwise consume. For reference, each kilogram of body fat is roughly equivalent to 32,300 kilojoules of food energy (i.e., {{convert|3,500|kcal/lb|kcal/kg|disp=or}}).<ref name=wish1958/> | |||

| ==Recommended daily intake== | |||

| Many countries and health organizations have published recommendations for healthy levels of daily intake of food energy. For example, the United States government estimates {{convert|2000|and|2600|kcal|kJ|abbr=on|order=flip}} needed for women and men, respectively, between ages 26 and 45, whose total physical activity is equivalent to walking around {{convert|1+1/2|to|3|mi|abbr=on|order=flip|round=0.5}} per day in addition to the activities of sedentary living. These estimates are for a "reference woman" who is {{convert|5|ft|4|in|m|2|abbr=on|order=flip}} tall and weighs {{convert|126|lb|kg|order=flip|abbr=on}} and a "reference man" who is {{convert|5|ft|10|in|m|2|abbr=on|order=flip}} tall and weighs {{convert|154|lb|kg|order=flip|abbr=on}}.<ref name=NIHrdi8/> Because caloric requirements vary by height, activity, age, pregnancy status, and other factors, the USDA created the DRI Calculator for Healthcare Professionals in order to determine individual caloric needs.<ref>{{cite web |title=Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020 - 2025 |url=https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf |website=dietaryguidelines.gov |publisher=USDA & HHS |access-date=17 May 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=DRI Calculator for Healthcare Professionals |url=https://www.nal.usda.gov/human-nutrition-and-food-safety/dri-calculator |website=usda.gov |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |access-date=17 May 2022}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ] of the ], the average minimum energy requirement per person per day is about {{convert|1800|kcal|kJ|abbr=on|order=flip}}.<ref name=FAO2014/> Although the U.S. has changed over time with a growth in population and processed foods or food in general, Americans today have available roughly the same level of calories as the older generation. | |||

| Older people and those with ]s require less energy; children and physically active people require more. Recognizing these factors, Australia's ] recommends different daily energy intakes for each age and gender group.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nrv.gov.au/energy.htm|title=Dietary Energy|access-date=27 September 2014}}</ref> Notwithstanding, nutrition labels on Australian food products typically recommend the average daily energy intake of {{convert|2100|kcal|kJ|abbr=on|order=flip}}. | |||

| The minimum food energy intake is also higher in cold environments. Increased mental activity has been linked with moderately increased ].<ref name=Lars1995/> | |||

| == Nutrition labels == | |||

| ] in the United Kingdom]] | |||

| Many governments ] the energy content of their products, to help consumers control their energy intake. To facilitate evaluation by consumers, food energy values (and other nutritional properties) in package labels or tables are often quoted for convenient amounts of the food, rather than per gram or kilogram; such as in "calories per serving" or "kcal per 100 g", or "kJ per package". The units vary depending on country: | |||

| {| class=wikitable | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Country !! Mandatory unit (symbol) !! Second unit (symbol) !! Common usage | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || Calorie (Cal)<ref name=CFR101/> || kilojoule (kJ), optional<ref name=CFR101/> || calorie (cal)<ref name=FDA2019/> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || Calorie (Cal) {{cn|date=January 2022}} || kilojoule (kJ), optional {{cn|date=January 2022}} || calorie (cal) {{cn|date=January 2022}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] and ] || kilojoule (kJ)<ref name=AUNZstd/><ref name=QLDH2017/> || kilocalorie (kcal), optional<ref name=AUNZstd/><ref name=QLDH2017/> || AU: kilocalorie (kcal) {{cn|date=January 2022}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || kJ<ref name=UKSI1996/> || kcal, mandatory<ref name=UKSI1996/> || | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || kilojoule (kJ)<ref name=EU2011/> || kilocalorie (kcal), mandatory<ref name=EU2011/> || | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || caloria or quilocaloria (kcal)<ref name=BRIN2020/> || || caloria | |||

| |} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] experiment showing food energy. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist|2|refs = | |||

| Health Canada (1997). p. 4 Retrieved Jan. 22, 2006. | |||

| <ref name=FDA2019>U. S. Food and Drug Administration (2019): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220120213703/http://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/calories-menu |date=2022-01-20 }}". Online document at the {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130915112715/https://www.fda.gov/ |date=2013-09-15 }}, dated 5 August 2019. Accessed on 2022-01-20.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=QLDH2017>{{Cite web|title=What's the difference between a calorie and a kilojoule|url=https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-events/news/calorie-kilojoule-difference-convert|date=21 February 2017|website=]|language=en-AU|access-date=29 May 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name=AUNZstd>{{Cite web|title=Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code – Standard 1.2.8 – Nutrition information requirements|url=http://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2018C00944/Html/Text|last=Health|website=www.legislation.gov.au|language=en|access-date=29 May 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name=EU2011>European Union Parliament (2011): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220111164645/https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:02011R1169-20180101&from=EN |date=2022-01-11 }}" Document 02011R1169-20180101</ref> | |||

| <ref name=CFR101>United States Federal Government (1977), " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220121072942/https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-101 |date=2022-01-21 }}", from Federal Register 14308, 15 March 1977.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=youd2021>Adrienne Youdim (2021): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130804173559/http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/disorders_of_nutrition/overview_of_nutrition/calories.html |date=2013-08-04 }}". Article in the ''Merck Manual Home Edition'' online, dated Dec/2011. Accessed on 21 February 2022</ref> | |||

| <ref name=SciAm>{{Cite news|url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-do-food-manufacturers/|title=How Do Food Manufacturers Calculate the Calorie Count of Packaged Foods?|work=Scientific American|access-date=8 September 2017|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=CANH1997>{{cite web|work=Health Canada, ] p. 4|year =1997|url=http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/fiche-nutri-data/nutrient_value-valeurs_nutritives-eng.php|format=PDF|title=Nutrient Value of Some Common Foods|access-date=25 January 2015}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=marsh2020>Allison Marsh (2020): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220121000718/https://spectrum.ieee.org/how-counting-calories-became-a-science |date=2022-01-21 }}" Online article on the {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220120232140/https://spectrum.ieee.org/ |date=2022-01-20 }} website, dated 29 December 2020. Accessed on 2022-01-20.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=triv2009> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111113173259/http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20327171.200-the-calorie-delusion-why-food-labels-are-wrong.html?full=true |date=2011-11-13 }} by Bijal Trivedi, '']'', 18 July 2009, pp. 30-3.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=UKSI1996>United Kingdom {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130921164025/http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1996/1499/contents/made |date=2013-09-21 }} – {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130317110033/http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1996/1499/schedule/7/made |date=2013-03-17 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=EUtab1990>{{Cite web |url=http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1990L0496:20081211:EN:PDF |title=Council directive 90/496/EEC of 24 September 1990 on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs |access-date=18 March 2010 |archive-date=3 October 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111003093749/http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1990L0496:20081211:EN:PDF |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=BRIN2020>Ministério da Saúde, Brazil (2020): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220121023715/https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-in-n-75-de-8-de-outubro-de-2020-282071143 |date=2022-01-21 }}", dated 2020-10-08, published on Diário Oficial da União on 2020-10-09, page 113.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="seiler">Stephen Seiler, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071221225027/http://home.hia.no/~stephens/effiperf.htm |date=2007-12-21 }} (1996, 2005).</ref> | |||

| <ref name=concept2> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101226185824/http://www.concept2.com/us/support/manuals/pdf/B_UsersManual.pdf |date=2010-12-26 }} (1993).</ref> | |||

| <ref name=wish1958>Wishnofsky, M. Caloric Equivalents of Gained or Lost Weight. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, (1958).</ref> | |||

| <ref name=guyt2006>Guyton A. C., Hall J. E. Textbook of medical physiology, 11 ed., p. 887, Elsevier Saunders, 2006.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=jeff2006>{{cite journal | author = Jeffrey S. F. | year = 2006 | title = Regulating Energy Balance: The Substrate Strikes Back | journal = Science | pages = 861–864 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=garl2005>Garlick, P. J. The role of leucine in the regulation of protein metabolism. Journal of Nutrition, 2005. 135(6): 1553S–6S.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=ross2000>Ross, K. A. (2000c) Energy and fuel, in Littledyke M., Ross K. A. and Lakin E. (eds), Science Knowledge and the Environment. London: David Fulton Publishers.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=NIHrdi8>US National Institutes of Health (2015): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160301132440/http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/appendix-2/ |date=2016-03-01 }}"</ref> | |||

| <ref name=FAO2003>United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (2003): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100524003622/http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/006/Y5022E/y5022e04.htm |date=2010-05-24 }}". Accessed on 21 January 2022.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Lars1995> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121023174100/http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/els/01602896/1995/00000021/00000003/art90017;jsessionid=1vc0khhvsj1vg.alice?format=print |date=2012-10-23 }}, Intelligence, Volume 21, Number 3, November 1995 , pp. 267-278(12), 1995.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=FAO2014>United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (2014): " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091220202823/http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/#jfmulticontent_c130584-2 |date=2009-12-20 }}". Accessed on 27 September 2014</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Food science}} | |||

| {{Cellular respiration}} | |||

| {{MetabolismMap}} | |||

| {{citric acid cycle}} | |||

| {{Citric acid cycle enzymes}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Food Energy}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:24, 15 December 2024

Chemical energy animals derive from foodFood energy is chemical energy that animals (including humans) derive from their food to sustain their metabolism, including their muscular activity.

Most animals derive most of their energy from aerobic respiration, namely combining the carbohydrates, fats, and proteins with oxygen from air or dissolved in water. Other smaller components of the diet, such as organic acids, polyols, and ethanol (drinking alcohol) may contribute to the energy input. Some diet components that provide little or no food energy, such as water, minerals, vitamins, cholesterol, and fiber, may still be necessary to health and survival for other reasons. Some organisms have instead anaerobic respiration, which extracts energy from food by reactions that do not require oxygen.

The energy contents of a given mass of food is usually expressed in the metric (SI) unit of energy, the joule (J), and its multiple the kilojoule (kJ); or in the traditional unit of heat energy, the calorie (cal). In nutritional contexts, the latter is often (especially in US) the "large" variant of the unit, also written "Calorie" (with symbol Cal, both with capital "C") or "kilocalorie" (kcal), and equivalent to 4184 J or 4.184 kJ. Thus, for example, fats and ethanol have the greatest amount of food energy per unit mass, 37 and 29 kJ/g (9 and 7 kcal/g), respectively. Proteins and most carbohydrates have about 17 kJ/g (4 kcal/g), though there are differences between different kinds. For example, the values for glucose, sucrose, and starch are 15.57, 16.48 and 17.48 kilojoules per gram (3.72, 3.94 and 4.18 kcal/g) respectively. The differing energy density of foods (fat, alcohols, carbohydrates and proteins) lies mainly in their varying proportions of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. Carbohydrates that are not easily absorbed, such as fibre, or lactose in lactose-intolerant individuals, contribute less food energy. Polyols (including sugar alcohols) and organic acids contribute 10 kJ/g (2.4 kcal/g) and 13 kJ/g (3.1 kcal/g) respectively.

The energy contents of a complex dish or meal can be approximated by adding the energy contents of its components.

History and methods of measurement

Direct calorimetry of combustion

The first determinations of the energy content of food were made by burning a dried sample in a bomb calorimeter and measuring the temperature change in the water surrounding the apparatus, a method known as direct calorimetry.

The Atwater system

Main article: Atwater systemHowever, the direct calorimetric method generally overestimates the actual energy that the body can obtain from the food, because it also counts the energy contents of dietary fiber and other indigestible components, and does not allow for partial absorption and/or incomplete metabolism of certain substances. For this reason, today the energy content of food is instead obtained indirectly, by using chemical analysis to determine the amount of each digestible dietary component (such as protein, carbohydrates, and fats), and adding the respective food energy contents, previously obtained by measurement of metabolic heat released by the body. In particular, the fibre content is excluded. This method is known as the Modified Atwater system, after Wilbur Atwater who pioneered these measurements in the late 19th century.

The system was later improved by Annabel Merrill and Bernice Watt of the USDA, who derived a system whereby specific calorie conversion factors for different foods were proposed.

Dietary sources of energy

The typical human diet consists chiefly of carbohydrates, fats, proteins, water, ethanol, and indigestible components such as bones, seeds, and fibre (mostly cellulose). Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins typically comprise ninety percent of the dry weight of food. Ruminants can extract food energy from the respiration of cellulose because of bacteria in their rumens that decompose it into digestible carbohydrates.

Other minor components of the human diet that contribute to its energy content are organic acids such as citric and tartaric, and polyols such as glycerol, xylitol, inositol, and sorbitol.

Some nutrients have regulatory roles affected by cell signaling, in addition to providing energy for the body. For example, leucine plays an important role in the regulation of protein metabolism and suppresses an individual's appetite. Small amounts of essential fatty acids, constituents of some fats that cannot be synthesized by the human body, are used (and necessary) for other biochemical processes.

The approximate food energy contents of various human diet components, to be used in package labeling according to the EU regulations and UK regulations, are:

| Food component | Energy density | |

|---|---|---|

| kJ/g | kcal/g | |

| Fat | 37 | 9 |

| Ethanol | 29 | 7 |

| Proteins | 17 | 4 |

| Carbohydrates | 17 | 4 |

| Organic acids | 13 | 3 |

| Polyols (sugar alcohols, sweeteners) (1) | 10 | 2.4 |

| Fiber (2) | 8 | 2 |

(1) Some polyols, like erythritol, are not digested and should be excluded from the count.

(2) This entry exists in the EU regulations of 2008, but not in the UK regulations, according to which fibre shall not be counted.

More detailed tables for specific foods have been published by many organizations, such as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization also has published a similar table.

Other components of the human diet are either noncaloric, or are usually consumed in such small amounts that they can be neglected.

Energy usage in the human body

Main articles: Bioenergetics and Energy balance (biology)The food energy actually obtained by respiration is used by the human body for a wide range of purposes, including basal metabolism of various organs and tissues, maintaining the internal body temperature, and exerting muscular force to maintain posture and produce motion. About 20% is used for brain metabolism.

The conversion efficiency of energy from respiration into muscular (physical) power depends on the type of food and on the type of physical energy usage (e.g., which muscles are used, whether the muscle is used aerobically or anaerobically). In general, the efficiency of muscles is rather low: only 18 to 26% of the energy available from respiration is converted into mechanical energy. This low efficiency is the result of about 40% efficiency of generating ATP from the respiration of food, losses in converting energy from ATP into mechanical work inside the muscle, and mechanical losses inside the body. The latter two losses are dependent on the type of exercise and the type of muscle fibers being used (fast-twitch or slow-twitch). For an overall efficiency of 20%, one watt of mechanical power is equivalent to 18 kJ/h (4.3 kcal/h). For example, a manufacturer of rowing equipment shows calories released from "burning" food as four times the actual mechanical work, plus 1,300 kJ (300 kcal) per hour, which amounts to about 20% efficiency at 250 watts of mechanical output. It can take up to 20 hours of little physical output (e.g., walking) to "burn off" 17,000 kJ (4,000 kcal) more than a body would otherwise consume. For reference, each kilogram of body fat is roughly equivalent to 32,300 kilojoules of food energy (i.e., 3,500 kilocalories per pound or 7,700 kilocalories per kilogram).

Recommended daily intake

Many countries and health organizations have published recommendations for healthy levels of daily intake of food energy. For example, the United States government estimates 8,400 and 10,900 kJ (2,000 and 2,600 kcal) needed for women and men, respectively, between ages 26 and 45, whose total physical activity is equivalent to walking around 2.5 to 5 km (1+1⁄2 to 3 mi) per day in addition to the activities of sedentary living. These estimates are for a "reference woman" who is 1.63 m (5 ft 4 in) tall and weighs 57 kg (126 lb) and a "reference man" who is 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in) tall and weighs 70 kg (154 lb). Because caloric requirements vary by height, activity, age, pregnancy status, and other factors, the USDA created the DRI Calculator for Healthcare Professionals in order to determine individual caloric needs.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the average minimum energy requirement per person per day is about 7,500 kJ (1,800 kcal). Although the U.S. has changed over time with a growth in population and processed foods or food in general, Americans today have available roughly the same level of calories as the older generation.

Older people and those with sedentary lifestyles require less energy; children and physically active people require more. Recognizing these factors, Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council recommends different daily energy intakes for each age and gender group. Notwithstanding, nutrition labels on Australian food products typically recommend the average daily energy intake of 8,800 kJ (2,100 kcal).

The minimum food energy intake is also higher in cold environments. Increased mental activity has been linked with moderately increased brain energy consumption.

Nutrition labels

Many governments require food manufacturers to label the energy content of their products, to help consumers control their energy intake. To facilitate evaluation by consumers, food energy values (and other nutritional properties) in package labels or tables are often quoted for convenient amounts of the food, rather than per gram or kilogram; such as in "calories per serving" or "kcal per 100 g", or "kJ per package". The units vary depending on country:

| Country | Mandatory unit (symbol) | Second unit (symbol) | Common usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Calorie (Cal) | kilojoule (kJ), optional | calorie (cal) |

| Canada | Calorie (Cal) | kilojoule (kJ), optional | calorie (cal) |

| Australia and New Zealand | kilojoule (kJ) | kilocalorie (kcal), optional | AU: kilocalorie (kcal) |

| United Kingdom | kJ | kcal, mandatory | |

| European Union | kilojoule (kJ) | kilocalorie (kcal), mandatory | |

| Brazil | caloria or quilocaloria (kcal) | caloria |

See also

- Atwater system

- Basal metabolic rate

- Calorie

- Chemical energy

- Food chain

- Food composition

- Heat of combustion

- Nutrition facts label

- Satiety value

- Table of food nutrients

- List of countries by food energy intake

References

- ^ Allison Marsh (2020): "How Counting Calories Became a Science: Calorimeters defined the nutritional value of food and the output of steam generators Archived 2022-01-21 at the Wayback Machine" Online article on the IEEE Spectrum Archived 2022-01-20 at the Wayback Machine website, dated 29 December 2020. Accessed on 2022-01-20.

- Ross, K. A. (2000c) Energy and fuel, in Littledyke M., Ross K. A. and Lakin E. (eds), Science Knowledge and the Environment. London: David Fulton Publishers.

- ^ United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (2003): "FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 77: Food energy - methods of analysis and conversion factors Archived 2010-05-24 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed on 21 January 2022.

- "Schedule 7: Nutrition labelling". Legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 1 July 1996. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Adrienne Youdim (2021): "Calories Archived 2013-08-04 at the Wayback Machine". Article in the Merck Manual Home Edition online, dated Dec/2011. Accessed on 21 February 2022

- "Nutrient Value of Some Common Foods" (PDF). Health Canada, PDF p. 4. 1997. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "How Do Food Manufacturers Calculate the Calorie Count of Packaged Foods?". Scientific American. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Why food labels are wrong" Archived 2011-11-13 at the Wayback Machine by Bijal Trivedi, New Scientist, 18 July 2009, pp. 30-3.

- Annabel Merrill; Bernice Watt (1973). Energy Values of Food ... basis and derivation (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2016.

- "Carbohydrates, Proteins, Nutrition". The Merck Manual.

- Jeffrey S. F. (2006). "Regulating Energy Balance: The Substrate Strikes Back". Science: 861–864.

- Garlick, P. J. The role of leucine in the regulation of protein metabolism. Journal of Nutrition, 2005. 135(6): 1553S–6S.

- ^ "Council directive 90/496/EEC of 24 September 1990 on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs". Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ United Kingdom The Food Labelling Regulations 1996 Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine – Schedule 7: Nutrition labelling Archived 2013-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Stephen Seiler, Efficiency, Economy and Endurance Performance Archived 2007-12-21 at the Wayback Machine (1996, 2005).

- Concept II Rowing Ergometer, user manual Archived 2010-12-26 at the Wayback Machine (1993).

- Guyton A. C., Hall J. E. Textbook of medical physiology, 11 ed., p. 887, Elsevier Saunders, 2006.

- Wishnofsky, M. Caloric Equivalents of Gained or Lost Weight. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, (1958).

- US National Institutes of Health (2015): "Dietary guidelines Archived 2016-03-01 at the Wayback Machine"

- "Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020 - 2025" (PDF). dietaryguidelines.gov. USDA & HHS. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- "DRI Calculator for Healthcare Professionals". usda.gov. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (2014): "Hunger Archived 2009-12-20 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed on 27 September 2014

- "Dietary Energy". Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Evaluation of a mental effort hypothesis for correlations between cortical metabolism and intelligence Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Intelligence, Volume 21, Number 3, November 1995 , pp. 267-278(12), 1995.

- ^ United States Federal Government (1977), "Code of Federal Regulations - Part 101 - Food labeling Archived 2022-01-21 at the Wayback Machine", from Federal Register 14308, 15 March 1977.

- U. S. Food and Drug Administration (2019): "Calories on the Menu - Information for Archived 2022-01-20 at the Wayback Machine". Online document at the FDA Website Archived 2013-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, dated 5 August 2019. Accessed on 2022-01-20.

- ^ Health. "Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code – Standard 1.2.8 – Nutrition information requirements". www.legislation.gov.au. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "What's the difference between a calorie and a kilojoule". Queensland Health. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ European Union Parliament (2011): "Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 Archived 2022-01-11 at the Wayback Machine" Document 02011R1169-20180101

- Ministério da Saúde, Brazil (2020): "Instrução Normativa Nº 75 - Estabelece os requisitos técnicos para declaração da rotulagem nutricional nos alimentos embalados Archived 2022-01-21 at the Wayback Machine", dated 2020-10-08, published on Diário Oficial da União on 2020-10-09, page 113.

External links

| Metabolism, catabolism, anabolism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Energy metabolism |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Specific paths |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

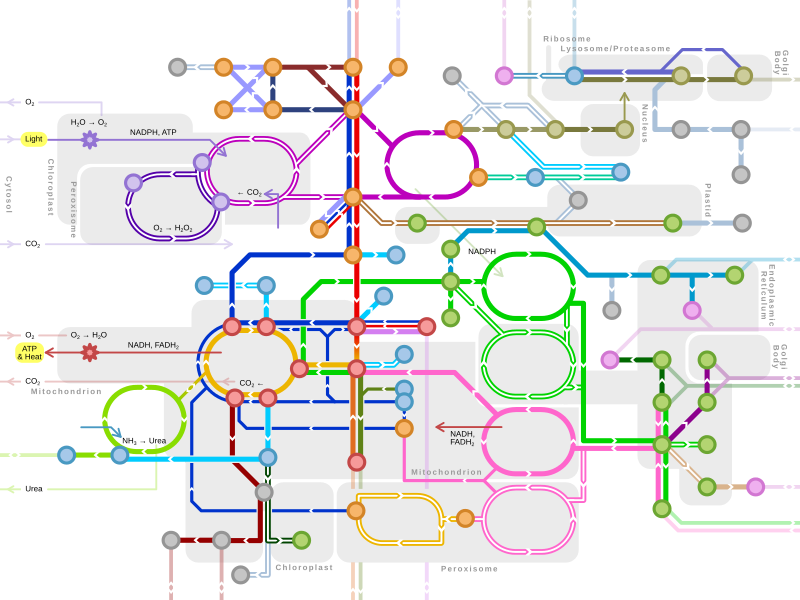

| Metabolism map | ||

|---|---|---|

Single lines: pathways common to most lifeforms. Double lines: pathways not in humans (occurs in e.g. plants, fungi, prokaryotes). | ||

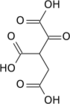

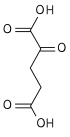

| Citric acid cycle metabolic pathway | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Metabolism: Citric acid cycle enzymes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | |||||||||

| Anaplerotic |

| ||||||||

| Mitochondrial electron transport chain/ oxidative phosphorylation |

| ||||||||