| Revision as of 13:28, 16 May 2012 view sourceMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,292 editsm Reverted edits by 173.184.63.186 (talk) to last version by Materialscientist← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:01, 21 December 2024 view source GreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,555,767 edits Rescued 4 archive links; reformat 4 links. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Outcrop of rock in the sea formed by the growth and deposit of stony coral skeletons}} | |||

| {{ocean habitat topics|image=Blue Linckia Starfish.JPG|thumb|caption=] of a coral reef}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{use British English|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=August 2021}} | |||

| ] of a coral reef|thumb]] | |||

| '''Coral reefs''' are underwater structures made from ] secreted by ]s. Coral reefs are colonies of tiny living animals found in marine waters that contain few nutrients. Most coral reefs are built from ]s, which in turn consist of ]s that cluster in groups. The polyps are like tiny ]s, to which they are closely related. Unlike sea anemones, coral polyps secrete hard carbonate ]s which support and protect their bodies. Reefs grow best in warm, shallow, clear, sunny and agitated waters. | |||

| {{Ocean habitat topics}} | |||

| A '''coral reef''' is an underwater ] characterized by reef-building ]s. Reefs are formed of ] of ] ]s held together by ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://coral.org/en/coral-reefs-101/how-reefs-are-made/|title=How Reefs Are Made|date=2021|website=Coral Reef Alliance|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211030053454/https://coral.org/en/coral-reefs-101/how-reefs-are-made/|archive-date=30 October 2021|access-date=19 April 2022}}</ref> Most coral reefs are built from ]s, whose polyps cluster in groups. | |||

| Coral belongs to the ] ] in the animal ] ], which includes ]s and ]. Unlike sea anemones, corals secrete hard carbonate ]s that support and protect the coral. Most reefs grow best in warm, shallow, clear, sunny and agitated water. Coral reefs first appeared 485 million years ago, at the dawn of the ], displacing the microbial and ] reefs of the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=Jeong-Hyun |last2=Chen |first2=Jitao |last3=Chough |first3=Sung Kwun |title=The middle–late Cambrian reef transition and related geological events: A review and new view |journal=Earth-Science Reviews |date=1 June 2015 |volume=145 |pages=66–84 |doi=10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.03.002 |bibcode=2015ESRv..145...66L |issn=0012-8252}}</ref> | |||

| Often called “rainforests of the sea”, coral reefs form some of the most diverse ]s on Earth. They occupy less than 0.1% of the world's ocean surface, about half the area of France, yet they provide a home for 25% of all marine ],<ref>Spalding MD and Grenfell AM (1997) '''Coral Reefs'', '''16''' (4):225–230. {{doi|10.1007/s003380050078}}</ref><ref name="Spalding" /><ref name=Mulhall>Mulhall M (2007) Duke Environmental Law and Policy Forum '''19''':321–351.</ref> | |||

| including ], ]s, ]s, ], ]s, ]s, ]s and other ].<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |title=Hawai{{okina}}i's Sea Creatures | |||

| |last=Hoover |first=John | |||

| |isbn=15854702902 {{Please check ISBN|reason=Invalid length.}} | |||

| |publisher=Mutual | |||

| |date=November, 2007}}</ref> | |||

| ], coral reefs flourish even though they are surrounded by ocean waters that provide few nutrients. They are most commonly found at shallow depths in tropical waters, but ] and cold water corals also exist on smaller scales in other areas. | |||

| Sometimes called ''rainforests of the sea'',<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100210050558/https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/oceans/corals/ |date=10 February 2010 }} ''NOAA National Ocean Service''. Accessed: 10 January 2020.</ref> shallow coral reefs form some of Earth's most diverse ecosystems. They occupy less than 0.1% of the world's ocean area, about half the area of France, yet they provide a home for at least 25% of all marine ],<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Spalding MD, Grenfell AM |doi=10.1007/s003380050078| title=New estimates of global and regional coral reef areas| year=1997| journal=Coral Reefs| volume=16| issue=4| pages=225–230 |bibcode=1997CorRe..16..225S |s2cid=46114284}}</ref><ref name="Spalding"/><ref name="Mulhall">{{cite journal|last1=Mulhall|first1= M. |date=Spring 2009|url=http://www.law.duke.edu/shell/cite.pl?19+Duke+Envtl.+L.+&+Pol%27y+F.+321+pdf |title=Saving rainforests of the sea: An analysis of international efforts to conserve coral reefs |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100106053233/http://www.law.duke.edu/shell/cite.pl?19+Duke+Envtl.+L.+&+Pol%27y+F.+321+pdf |archive-date=6 January 2010|journal=Duke Environmental Law and Policy Forum |volume=19|pages=321–351}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Where are Corals Found? |url=http://coralreef.noaa.gov/aboutcorals/coral101/corallocations/|website=NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program|publisher=]|date=13 May 2011|access-date=24 March 2015|url-status=dead<!--Maybe this will work when Internet Archive is not fund raising-->|archive-date=2016-03-04|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160304053758/http://coralreef.noaa.gov/aboutcorals/coral101/corallocations/ }}</ref> including ], ]s, ]s, ], ]s, ]s, ]s and other ].<ref>{{cite book |url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=TxrHBCs1u4EC}}|title=Hawaiʻi's Sea Creatures |last=Hoover |first=John |isbn=978-1-56647-220-3 |publisher=Mutual |date=November 2007}}</ref> Coral reefs flourish in ocean waters that provide few nutrients. They are most commonly found at shallow depths in tropical waters, but ] and cold water coral reefs exist on smaller scales in other areas. | |||

| Coral reefs deliver ] to tourism, fisheries and ]. The annual global economic value of coral reefs has been estimated at $US375 billion. However, coral reefs are fragile ecosystems, partly because they are very sensitive to water temperature. They are under threat from ], ], ], ] for ], overuse of reef resources, and harmful land-use practices, including urban and ] and ], which can harm reefs by encouraging excess ] growth.<ref name="Corals reveal impact of land use">{{cite web| url=http://www.coralcoe.org.au/news_stories/landimpacts.html | title= Corals reveal impact of land use | accessdate = 12 July 2007 | publisher=ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.hcri.ssri.hawaii.edu/files/media/pr-water_quality.pdf | |||

| Shallow tropical coral reefs have declined by 50% since 1950, partly because they are sensitive to water conditions.<ref>{{Cite web |first=Patrick |last=Greenfield |date=2021-09-17|title=Global coral cover has fallen by half since 1950s, analysis finds |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/17/global-coral-cover-halves-since-1950s-analysis-finds-aoe|access-date=2021-09-18|website=The Guardian}}</ref> They are under threat from ] (nitrogen and phosphorus), rising ] and ], overfishing (e.g., from ], ], ] on ]), sunscreen use,<ref name="Sunscreen">{{cite journal |last1=Danovaro|first1=Roberto|last2=Bongiorni|first2=Lucia|last3=Corinaldesi|first3=Cinzia |last4=Giovannelli|first4=Donato|last5=Damiani|first5=Elisabetta|last6=Astolfi |first6=Paola|last7=Greci |first7=Lucedio|last8=Pusceddu|first8=Antonio|date=April 2008|title=Sunscreens Cause Coral Bleaching by Promoting Viral Infections|journal=Environmental Health Perspectives|volume=116|issue=4 |pages=441–447 |doi=10.1289/ehp.10966|pmc=2291018|pmid=18414624}}</ref> and harmful land-use practices, including ] and seeps (e.g., from ]s and cesspools).<ref name="Corals reveal impact of land use">{{cite web|title=Corals reveal impact of land use |url=http://www.uq.edu.au/news/?article=12183|access-date=September 21, 2013|publisher=ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Minato|first=Charissa|date=July 1, 2002 |title=Urban runoff and coastal water quality being researched for effects on coral reefs |url=http://www.hcri.ssri.hawaii.edu/files/media/pr-water_quality.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100610170312/http://www.hcri.ssri.hawaii.edu/files/media/pr-water_quality.pdf|archive-date=June 10, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=July 1998 |title=Coastal Watershed Factsheets – Coral Reefs and Your Coastal Watershed |publisher=Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water |url=http://water.epa.gov/type/oceb/fact4.cfm |url-status=dead |archive-date=2010-08-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100830153311/http://water.epa.gov/type/oceb/fact4.cfm}}</ref> | |||

| |title=Urban runoff and coastal water quality being researched for effects on coral reefs | |||

| |first=Charissa |last=Minato | |||

| Coral reefs deliver ] for tourism, fisheries and ]. The annual global economic value of coral reefs has been estimated at anywhere from US$30–375 billion (1997 and 2003 estimates)<ref name="Cesar" /><ref name="Costanza" /> to US$2.7 trillion (a 2020 estimate)<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Sixth Status of Corals of the World: 2020 Report|website=GCRMN |url=https://gcrmn.net/2020-report/ |access-date=2021-10-05}}</ref> to US$9.9 trillion (a 2014 estimate).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Costanza |first1=Robert |last2=de Groot |first2=Rudolph |last3=Sutton |first3=Paul |title=Changes in the global value of ecosystem services |journal=Global Environmental Change |date=2014 |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=152–158 |doi=10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002|bibcode=2014GEC....26..152C |s2cid=15215236 |url=https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10189453/ }}</ref> | |||

| |date=July 1, 2002 | |||

| |accessdate=December, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| Though the shallow water tropical coral reefs are best known, there are also deeper water reef-forming corals, which live in colder water and in temperate seas. | |||

| |url=http://water.epa.gov/type/oceb/fact4.cfm | |||

| |title=Coastal Watershed Factsheets – Coral Reefs and Your Coastal Watershed | |||

| |publisher=Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water | |||

| |epa= 842-F-98-008 | |||

| |date=July 1998 | |||

| |accessdate=December, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| {{toclimit|2}} | |||

| == Formation == | == Formation == | ||

| {{ |

{{Further|Atoll|Fringing reef|The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs}} | ||

| Most coral reefs were formed after the ] when melting ice caused |

Most coral reefs were formed after the ] when melting ice caused ] to rise and flood ]. Most coral reefs are less than 10,000 years old. As communities established themselves, the reefs grew upwards, pacing rising ]s. Reefs that rose too slowly could become drowned, without sufficient light.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.eoearth.org/article/Coral_reef#Types_of_Coral_Reefs |title=Coral reef |last=Kleypas |first=Joanie |date=2010 |website=The Encyclopedia of Earth |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100815052312/http://www.eoearth.org/article/Coral_reef |archive-date=August 15, 2010 |url-status=dead |access-date=April 4, 2011}}</ref> Coral reefs are also found in the deep sea away from ], around ] and ]s. The majority of these islands are ] in origin. Others have ] origins where ] lifted the deep ocean floor. | ||

| In '']'',<ref name="The structure and distribution of coral reefs">{{cite book|last=Darwin|first=Charles R.|title=The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs. Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836.|year=1842|publisher=Smith Elder and Co.|location=London |url=http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?viewtype=text&itemID=F271&pageseq=1}} </ref> ] set out his theory of the formation of atoll reefs, an idea he conceived during the ]. He theorized that ] and ] of Earth's ] under the oceans formed the atolls.<ref name=cr>{{Cite web|url=http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Chancellor_CoralReefs.html |title=Introduction to ''Coral reefs'' |author=Chancellor, Gordon |year=2008 |publisher=Darwin Online |access-date=January 20, 2009}}</ref> Darwin set out a sequence of three stages in atoll formation. A ] forms around an extinct ] as the island and ocean floor subside. As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a barrier reef and ultimately an atoll reef. | |||

| In 1842 in his first ], '']''<ref>{{Cite document | |||

| | last= Darwin | |||

| | first= Charles | |||

| | year = 1842 | |||

| | title =The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs. Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836 | |||

| | publication-place = London | |||

| | publisher =Smith Elder and Co | |||

| | url =http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?viewtype=text&itemID=F271&pageseq=1}}</ref> ] set out his theory of the formation of ]s, an idea he conceived during the ]. He theorized ] and ] of the Earth's ] under the oceans formed the atolls.<ref name=cr>{{Cite document|url=http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Chancellor_CoralReefs.html |title=Introduction to Coral reefs |author=Gordon Chancellor |year=2008 |publisher=Darwin Online |accessdate=2009-01-20}}</ref> Darwin’s theory sets out a sequence of three stages in atoll formation. It starts with a ] forming around an extinct ] as the island and ocean floor subsides. As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a barrier reef, and ultimately an ]. | |||

| <gallery> | <gallery widths="120" heights="80"> | ||

| File:Atoll forming-volcano.png|Darwin’s theory starts with a ] which becomes extinct | |||

| File:Atoll forming-volcano.png|Darwin's theory starts with a ] which becomes extinct | |||

| File:Atoll forming-Fringing reef.png|As the island and ocean floor subside, coral growth builds a ], often including a shallow lagoon between the land and the main reef. | File:Atoll forming-Fringing reef.png|As the island and ocean floor subside, coral growth builds a ], often including a shallow lagoon between the land and the main reef. | ||

| File:Atoll forming-Barrier reef.png|As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a larger barrier reef further from the shore with a bigger and deeper ] inside. | File:Atoll forming-Barrier reef.png|As the subsidence continues, the fringing reef becomes a larger barrier reef further from the shore with a bigger and deeper ] inside. | ||

| Line 47: | Line 33: | ||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| Darwin predicted that underneath each lagoon would be a ] base, the remains of the original volcano. Subsequent |

Darwin predicted that underneath each ] would be a ] base, the remains of the original volcano.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2017-03-11|title=4 Main Theories of Coral Reefs and Atolls/Oceans/Geography|url=https://www.geographynotes.com/oceans/4-main-theories-of-coral-reefs-and-atolls-oceans-geography/2704|access-date=2020-08-01|website=Geography Notes|language=en-US}}</ref> Subsequent research supported this hypothesis. Darwin's theory followed from his understanding that coral polyps thrive in the ] where the water is agitated, but can only live within a limited depth range, starting just below low ]. Where the level of the underlying earth allows, the corals grow around the coast to form fringing reefs, and can eventually grow to become a barrier reef. | ||

| ] Ocean Education Service. Retrieved |

{{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120714035333/http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/corals/media/supp_coral04a.html |date=July 14, 2012 }} ] Ocean Education Service. Retrieved January 9, 2010.</ref>]] | ||

| Where the bottom is rising, fringing reefs can grow around the coast, but coral raised above sea level dies |

Where the bottom is rising, fringing reefs can grow around the coast, but coral raised above sea level dies. If the land subsides slowly, the fringing reefs keep pace by growing upwards on a base of older, dead coral, forming a barrier reef enclosing a lagoon between the reef and the land. A barrier reef can encircle an island, and once the island sinks below sea level a roughly circular atoll of growing coral continues to keep up with the sea level, forming a central lagoon. Barrier reefs and atolls do not usually form complete circles but are broken in places by storms. Like ], a rapidly subsiding bottom can overwhelm coral growth, killing the coral and the reef, due to what is called ''coral drowning''.<ref name="Webster Coral subsidence">{{cite journal|last=Webster|first=Jody M. |author2=Braga, Juan Carlos |author3=Clague, David A. |author4=Gallup, Christina |author5=Hein, James R. |author6=Potts, Donald C. |author7=Renema, Willem |author8=Riding, Robert |author9=Riker-Coleman, Kristin |author10=Silver, Eli |author11=Wallace, Laura M. |title=Coral reef evolution on rapidly subsiding margins|journal=Global and Planetary Change|date=1 March 2009 |volume=66 |issue=1–2|pages=129–148|doi=10.1016/j.gloplacha.2008.07.010 |bibcode=2009GPC....66..129W}}</ref> Corals that rely on ] can die when the water becomes too deep for their ] to adequately ], due to decreased light exposure.<ref name="Webster coral drowning">{{cite journal|last=Webster|first=Jody M. |author2=Clague, David A. |author3=Riker-Coleman, Kristin |author4=Gallup, Christina |author5=Braga, Juan C. |author6=Potts, Donald |author7=Moore, James G. |author8=Winterer, Edward L. |author9=Paull, Charles K. |title=Drowning of the −150 m reef off Hawaii: A casualty of global meltwater pulse 1A?|journal=Geology|date=1 January 2004|volume=32|issue=3|page=249 |doi=10.1130/G20170.1 |bibcode=2004Geo....32..249W}}</ref> | ||

| The two main variables determining the ], or shape, of coral reefs are the nature of the |

The two main variables determining the ], or shape, of coral reefs are the nature of the ] on which they rest, and the history of the change in sea level relative to that substrate. | ||

| The approximately 20,000 |

The approximately 20,000-year-old ] offers an example of how coral reefs formed on continental shelves. Sea level was then {{convert|120|m|ft|abbr=on}} lower than in the 21st century.<ref>{{cite report |year=2006 |title=Reef Facts for Tour Guides: A "big picture" view of the Great Barrier Reef |url=http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/12437/Reef-Facts-01.pdf |access-date=June 18, 2007 |publisher=Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070620013057/http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/12437/Reef-Facts-01.pdf |archive-date=June 20, 2007}}</ref><ref name="AIMSage">{{cite web |last=Tobin |first=Barry |title=How the Great Barrier Reef was formed |publisher=Australian Institute of Marine Science |orig-year=1998 |year=2003 |url=http://www.aims.gov.au/pages/research/project-net/reefs/apnet-reefs00.html |access-date=November 22, 2006 |url-status=dead |archive-date=October 5, 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061005122324/http://www.aims.gov.au/pages/research/project-net/reefs/apnet-reefs00.html}}</ref> As sea level rose, the water and the corals encroached on what had been hills of the Australian coastal plain. By 13,000 years ago, sea level had risen to {{convert|60|m|ft|abbr=on}} lower than at present, and many hills of the coastal plains had become ]. As sea level rise continued, water topped most of the continental islands. The corals could then overgrow the hills, forming ]s and reefs. Sea level on the Great Barrier Reef has not changed significantly in the last 6,000 years.<ref name="AIMSage"/> The age of living reef structure is estimated to be between 6,000 and 8,000 years.<ref name="CRCage">{{cite web|author=CRC Reef Research Centre Ltd |title=What is the Great Barrier Reef? |url=http://www.reef.crc.org.au/discover/coralreefs/coralgbr.html|access-date=May 28, 2006|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20060822015653/http://www.reef.crc.org.au/discover/coralreefs/coralgbr.html |archive-date=August 22, 2006 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Although the Great Barrier Reef formed along a continental shelf, and not around a volcanic island, Darwin's principles apply. Development stopped at the barrier reef stage, since Australia is not about to submerge. It formed the world's largest barrier reef, {{convert|300|–|1,000|m|ft|abbr=on}} from shore, stretching for {{convert|2,000|km|mi|abbr=on}}.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121024014723/http://www.stanford.edu/group/microdocs/typesofreefs.html |date=24 October 2012 }} Microdocs, Stanford Education. Retrieved January 10, 2010.</ref> | ||

| Healthy tropical coral reefs grow horizontally from 1 |

Healthy tropical coral reefs grow horizontally from {{convert|1|to|3|cm|in|abbr=on}} per year, and grow vertically anywhere from {{convert|1|to|25|cm|in|abbr=on}} per year; however, they grow only at depths shallower than {{convert|150|m|ft|abbr=on}} because of their need for sunlight, and cannot grow above sea level.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|author=MSN Encarta |year=2006 |title=Great Barrier Reef |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761575831/Great_Barrier_Reef.html|access-date=December 11, 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091028020755/http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761575831/Great_Barrier_Reef.html |archive-date=October 28, 2009 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | ||

| ===Material=== | |||

| As the name implies, coral reefs are made up of coral skeletons from mostly intact coral colonies. As other chemical elements present in corals become incorporated into the calcium carbonate deposits, ] is formed. However, shell fragments and the remains of ] such as the green-segmented ] '']'' can add to the reef's ability to withstand damage from storms and other threats. Such mixtures are visible in structures such as ].<ref name=murph>{{cite book |title=Coral Reefs: Cities Under The Seas |last=Murphy |first=Richard C. |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-87850-138-0 |publisher=The Darwin Press |url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=WyYVAQAAIAAJ}}}}</ref>{{page needed|date=November 2022}} | |||

| === In the geologic past === | |||

| ] | |||

| The times of maximum reef development were in the ] (513–501 ]), ] (416–359 Ma) and ] (359–299 Ma), owing to ] order ] corals, and ] (100–66 Ma) and ] (23 Ma–present), owing to ] ] corals.<ref>{{Citation |last=Hallock |first=Pamela |title=Reefs and Reef Limestones in Earth History |date=1997 |work=Life and Death of Coral Reefs |pages=13–42 |place=Boston, MA |publisher=Springer US |doi=10.1007/978-1-4615-5995-5_2 |doi-broken-date=2 November 2024 |isbn=978-0-412-03541-8}}</ref> | |||

| Not all reefs in the past were formed by corals: those in the ] (542–513 Ma) resulted from calcareous ] and ] (small animals with conical shape, probably related to ]) and in the ] (100–66 Ma), when reefs formed by a group of bivalves called ] existed; one of the valves formed the main conical structure and the other, much smaller valve acted as a cap.<ref name="Johnson_2002" /> | |||

| Measurements of the oxygen isotopic composition of the aragonitic skeleton of coral reefs, such as '']'', can indicate changes in ] and sea surface salinity conditions during the growth of the coral. This technique is often used by climate scientists to infer a region's ].<ref name="Cobb">{{cite journal |last1=Cobb |first1=K. |last2=Charles |first2=Christopher D. |last3=Cheng |first3=Hai |last4=Edwards |first4=R. Lawrence |year=2003 |title=El Nino/Southern Oscillation and tropical Pacific climate during the past millennium |url=http://eas8001.eas.gatech.edu/papers/Cobb_Nature_2003.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=Nature |volume=424 |issue=6946 |pages=271–276 |bibcode=2003Natur.424..271C |doi=10.1038/nature01779 |pmid=12867972 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120111134948/http://eas8001.eas.gatech.edu/papers/Cobb_Nature_2003.pdf |archive-date=January 11, 2012 |s2cid=6088699}}</ref> | |||

| ==Types== | ==Types== | ||

| Since Darwin's identification of the three classical reef formations – the fringing reef around a volcanic island becoming a barrier reef and then an atoll<ref>Hopley, David (ed.) ''Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs'' Dordrecht: Springer, 2011. p. 40.</ref> – scientists have identified further reef types. While some sources find only three,<ref>e.g. in the Coral Reef Ecology Curriculum. Retrieved 1 Feb 2018.</ref><ref>Whittow, John (1984). ''Dictionary of Physical Geography''. London: Penguin, 1984, p. 443. {{ISBN|0-14-051094-X}}.</ref> Thomas lists "Four major forms of large-scale coral reefs" – the fringing reef, barrier reef, atoll and table reef based on Stoddart, D.R. (1969).<ref name="Thomas">{{cite book |editor-last1=Thomas |editor-first1=David S. G. |title=The Dictionary of Physical Geography |date=2016 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons Inc. |location=Hoboken, NJ |isbn=9781118782347 |page=437 |edition=4th |url=https://geografiafisica.org/sem201901/geo112/bibliografia/articulos_libros/diccionario_de_geografia_fisica_Thomas_John_Wiley_Sons_2016_LIBRO_BUENO.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Stoddart">{{cite journal |last1=Stoddart |first1=D. R. |title=Ecology and morphology of recent coral reefs |journal=Biological Reviews |date=November 1969 |volume=44 |issue=4 |pages=433–498 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-185X.1969.tb00609.x |s2cid=85873056 }}</ref> Spalding ''et al.'' list four main reef types that can be clearly illustrated – the fringing reef, barrier reef, atoll, and "bank or platform reef"—and notes that many other structures exist which do not conform easily to strict definitions, including the "patch reef".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Spalding |first1=Mark |first2=Corinna |last2=Ravilious |first3= Edmund P. |last3=Green |title=World atlas of coral reefs |date=2001 |publisher=University of California Press |location=Berkeley |isbn=0-520-23255-0 |pages=16–}}</ref> | |||

| The three principal reef types are: | |||

| ===Fringing reef=== | |||

| * ''']''' – this type is directly attached to a shore, or borders it with an intervening shallow channel or lagoon. | |||

| ] at the southern tip of ]]] | |||

| * '''Barrier reef''' – a reef separated from a mainland or island shore by a deep channel or ] | |||

| {{main|Fringing reef}} | |||

| * ''']''' – this more or less circular or continuous barrier reef extends all the way around a lagoon without a central island. | |||

| ] | |||

| A fringing reef, also called a shore reef,<ref name=CRISG/> is directly attached to a shore,<ref> at www.pmfias.com. Retrieved 2 Feb 2018.</ref> or borders it with an intervening narrow, shallow channel or lagoon.<ref name=CRA/> It is the most common reef type.<ref name=CRA> at coral.org. Retrieved 2 Feb 2018.</ref> Fringing reefs follow coastlines and can extend for many kilometres.<ref>McClanahan, C.R.C. Sheppard and D.O. Obura. ''Coral Reefs of the Indian Ocean: Their Ecology and Conservation''. Oxford: OUP, 2000, p. 136.</ref> They are usually less than 100 metres wide, but some are hundreds of metres wide.<ref>Goudie, Andrew. ''Encyclopedia of Geomorphology'', London: Routledge, 2004, p. 411.</ref> Fringing reefs are initially formed on the shore at the ] level and expand seawards as they grow in size. The final width depends on where the sea bed begins to drop steeply. The surface of the fringe reef generally remains at the same height: just below the waterline. In older fringing reefs, whose outer regions pushed far out into the sea, the inner part is deepened by erosion and eventually forms a ].<ref>Ghiselin, Michael T. ''The Triumph of the Darwinian Method''. Berkeley, University of California, 1969, p. 22.</ref> Fringing reef lagoons can become over 100 metres wide and several metres deep. Like the fringing reef itself, they run parallel to the coast. The fringing reefs of the ] are "some of the best developed in the world" and occur along all its shores except off sandy bays.<ref>Hanauer, Eric. ''The Egyptian Red Sea: A Diver's Guide''. San Diego: Watersport, 1988, p. 74.</ref> | |||

| ===Barrier reef=== | |||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| ] in the |

] | ||

| Barrier reefs are separated from a mainland or island shore by a deep channel or ].<ref name=CRA/> They resemble the later stages of a fringing reef with its lagoon but differ from the latter mainly in size and origin. Their lagoons can be several kilometres wide and 30 to 70 metres deep. Above all, the offshore outer reef edge formed in open water rather than next to a shoreline. Like an atoll, it is thought that these reefs are formed either as the seabed lowered or sea level rose. Formation takes considerably longer than for a fringing reef, thus barrier reefs are much rarer. | |||

| The best known and largest example of a barrier reef is the Australian ].<ref name=CRA/><ref name=CRI> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170913053440/http://www.coral-reef-info.com/types-of-coral-reefs.html |date=September 13, 2017 }} at www.coral-reef-info.com. Retrieved 2 Feb 2018.</ref> Other major examples are the ] and the ].<ref name=CRI/> Barrier reefs are also found on the coasts of ],<ref name=CRI/> ], the ], on the southeast coast of ], on parts of the coast of ], southeastern ] and the south coast of the ]. | |||

| Other reef types or variants are: | |||

| * '''Patch reef''' – this type is an isolated, comparatively small reef outcrop, usually within a ] or ], often circular and surrounded by sand or seagrass. Patch reefs are common. | |||

| * '''Apron reef''' – a short reef resembling a fringing reef, but more sloped; extending out and downward from a point or peninsular shore | |||

| * '''Bank reef''' – a linear or semicircular shaped-outline, larger than a patch reef | |||

| * '''Ribbon reef''' – a long, narrow, possibly winding reef, usually associated with an atoll lagoon | |||

| * '''Table reef''' – an isolated reef, approaching an atoll type, but without a lagoon | |||

| * '''Habili''' – this is a reef in the ] that does not reach the surface near enough to cause visible ], although it may be a hazard to ships (from the ] for "unborn"). | |||

| * ''']''' – certain species of corals form communities called microatolls. The vertical growth of microatolls is limited by average tidal height. By analyzing growth morphologies, microatolls offer a low-resolution record of patterns of sea level change. Fossilized microatolls can also be dated using ]. Such methods have been used to reconstruct ] ]s.<ref name=Smithers> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | author = Smithers, S.G. and Woodroffe, C.D. | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | title = Microatolls as sea-level indicators on a mid-ocean atoll | |||

| | journal = Marine Geology | |||

| | volume = 168 | |||

| | issue = 1–4 | |||

| | pages = 61–78 | |||

| | doi = 10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00043-8 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ===Platform reef=== | |||

| * ''']s''' – are small, low-elevation, sandy islands formed on the surface of coral reefs. Material eroded from the reef piles up on parts of the reef or lagoon, forming an area above sea level. Plants can stabilize cays enough to become habitable by humans. Cays occur in tropical environments throughout the ], ] and ]s (including the Caribbean and on the ] and ]), where they provide habitable and agricultural land for hundreds of thousands of people. | |||

| ] | |||

| Platform reefs, variously called bank or table reefs, can form on the ], as well as in the open ocean, in fact anywhere where the seabed rises close enough to the surface of the ocean to enable the growth of zooxanthemic, reef-forming corals.<ref name=Leser>{{cite encyclopedia |editor=Leser, Hartmut |year=2005 |title=Wörterbuch Allgemeine Geographie |language=de |edition=13th dtv |location=Munich, DE |page=685 |isbn=978-3-423-03422-7}}</ref> Platform reefs are found in the southern Great Barrier Reef, the Swain<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Scoffin TP, Dixon JE |title=The distribution and structure of coral reefs: one hundred years since Darwin |journal=Biological Journal of the Linnean Society |year=1983 |volume=20 |pages=11–38|doi=10.1111/j.1095-8312.1983.tb01587.x }}</ref> and Capricorn Group<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:10881 |access-date=2018-06-28 |vauthors=Jell JS, Flood PG |title=Guide to the geology of reefs of the Capricorn and Bunker groups, Great Barrier Reef province |journal=Papers, Department of Geology |volume=8 |issue=3 |at=pp. 1–85, pls. 1–17 |date=Apr 1978}}</ref> on the continental shelf, about 100–200 km from the coast. Some platform reefs of the northern ] are several thousand kilometres from the mainland. Unlike fringing and barrier reefs which extend only seaward, platform reefs grow in all directions.<ref name=Leser/> They are variable in size, ranging from a few hundred metres to many kilometres across. Their usual shape is oval to elongated. Parts of these reefs can reach the surface and form sandbanks and small islands around which may form fringing reefs. A lagoon may form In the middle of a platform reef. | |||

| Platform reefs are typically situated within atolls, where they adopt the name "patch reefs" and often span a diameter of just a few dozen meters. In instances where platform reefs develop along elongated structures, such as old and weathered barrier reefs, they tend to arrange themselves in a linear formation. This is the case, for example, on the east coast of the ] near ]. In old platform reefs, the inner part can be so heavily eroded that it forms a pseudo-atoll.<ref name=Leser/> These can be distinguished from real atolls only by detailed investigation, possibly including core drilling. Some platform reefs of the ] are U-shaped, due to wind and water flow. | |||

| * When a coral reef cannot keep up with the sinking of a volcanic island, a ''']''' or ''']''' is formed. The tops of seamounts and guyots are below the surface. Seamounts are rounded at the top and guyots are flat. The flat top of the guyot, also called a ''tablemount'', is due to erosion by waves, winds, and atmospheric processes. | |||

| == |

===Atoll=== | ||

| {{main|Atoll}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Atolls or ]s are a more or less circular or continuous barrier reef that extends all the way around a lagoon without a central island.<ref>Hopley, David. ''Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs: Structure, Form and Process.'' Dordrecht: Springer, 2011, p. 51.</ref> They are usually formed from fringing reefs around volcanic islands.<ref name=CRA/> Over time, the island ] away and sinks below sea level.<ref name=CRA/> Atolls may also be formed by the sinking of the seabed or rising of the sea level. A ring of reefs results, which enclose a lagoon. Atolls are numerous in the South Pacific, where they usually occur in mid-ocean, for example, in the ], the ], ], the ] and ].<ref name=CRI/> | |||

| Atolls are found in the Indian Ocean, for example, in the ], the ], the ] and around ].<ref name=CRI/> The entire Maldives consist of 26 atolls.<ref> at www.mymaldives.com. Retrieved 2 Feb 2018.</ref> | |||

| Coral reef ecosystems contain distinct zones that represent different kinds of habitats. Usually, three major zones are recognized: the fore reef, reef crest, and the back reef (frequently referred to as the reef lagoon). | |||

| ===Other reef types or variants=== | |||

| All three zones are physically and ecologically interconnected. Reef life and oceanic processes create opportunities for exchange of ], ]s, nutrients, and marine life among one another. | |||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| * '''Apron reef''' – short reef resembling a fringing reef, but more sloped; extending out and downward from a point or peninsular shore. The initial stage of a fringing reef.<ref name=CRISG>National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ''Coral Reef Information System Glossary'', 2014.</ref> | |||

| Thus, they are integrated components of the coral reef ecosystem, each playing a role in the support of the reefs' abundant and diverse fish assemblages. | |||

| * '''Bank reef''' – isolated, flat-topped reef larger than a patch reef and usually on mid-shelf regions and linear or semi-circular in shape; a type of platform reef.<ref name=CRI/> | |||

| * '''Patch reef''' – common, isolated, comparatively small reef outcrop, usually within a ] or ], often circular and surrounded by sand or ]. Can be considered as a type of platform reef {{who|date=April 2019}} or as features of fringing reefs, atolls and barrier reefs.<ref name=CRI/> The patches may be surrounded by a ring of reduced seagrass cover referred to as a ''grazing halo''.<ref>{{citation|first1=Hugh|last1=Sweatman|first2=D. Ross|last2=Robertson|date=1994|title=Grazing halos and predation on juvenile Caribbean surgeonfishes|journal=Marine Ecology Progress Series|volume=111|issue=1–6|page=1|doi=10.3354/meps111001|bibcode=1994MEPS..111....1S|url=https://www.int-res.com/articles/meps/111/m111p001.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://www.int-res.com/articles/meps/111/m111p001.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live|access-date=24 April 2019|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Ribbon reef''' – long, narrow, possibly winding reef, usually associated with an atoll lagoon. Also called a shelf-edge reef or sill reef.<ref name=CRISG/> | |||

| * '''Drying reef''' – a part of a reef which is above water at low tide but submerged at high tide<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Beazley |first=P. B. |date=1991-01-01 |title=Reefs and the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea |url=https://brill.com/view/journals/ijec/6/4/article-p281_1.xml |journal=International Journal of Estuarine and Coastal Law |language=en |volume=6 |issue=4 |pages=281–312 |doi=10.1163/187529991X00162 |issn=0268-0106}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Habili''' – reef specific to the ]; does not reach near enough to the surface to cause visible ]; may be a hazard to ships (from the ] for "unborn") | |||

| * ''']''' – community of species of corals; vertical growth limited by average tidal height; growth morphologies offer a low-resolution record of patterns of sea level change; fossilized remains can be dated using ] and have been used to reconstruct ] ]s<ref name=Smithers>{{cite journal |author1=Smithers, S.G. |author2=Woodroffe, C.D. |year=2000 |title=Microatolls as sea-level indicators on a mid-ocean atoll |journal=Marine Geology |volume=168 |issue=1–4 |pages=61–78 |doi=10.1016/S0025-3227(00)00043-8| bibcode=2000MGeol.168...61S}}</ref> | |||

| * ''']s''' – small, low-elevation, sandy islands formed on the surface of coral reefs from eroded material that piles up, forming an area above sea level; can be stabilized by plants to become habitable; occur in tropical environments throughout the ], ] and ]s (including the Caribbean and on the ] and Belize Barrier Reef), where they provide habitable and agricultural land | |||

| * ''']''' or ''']''' – formed when a coral reef on a volcanic island subsides; tops of seamounts are rounded and guyots are flat; flat tops of guyots, or ''tablemounts'', are due to erosion by waves, winds, and atmospheric processes | |||

| == Zones == | |||

| Most coral reefs exist in shallow waters less than 50 m deep. Some inhabit tropical continental shelves where cool, nutrient rich ] does not occur, such as ]. Others are found in the deep ocean surrounding islands or as ]s, such as in the ]. The reefs surrounding islands form when islands subside into the ocean, and atolls form when an island subsides below the surface of the sea. | |||

| ] | |||

| Coral reef ecosystems contain distinct zones that host different kinds of habitats. Usually, three major zones are recognized: the fore reef, reef crest, and the back reef (frequently referred to as the reef lagoon). | |||

| Alternatively, Moyle and Cech distinguish six zones, though most reefs possess only some of the zones.<ref name=MoyleCech556>{{harvnb|Moyle|Cech|2003|p=556}}</ref> | |||

| The three zones are physically and ecologically interconnected. Reef life and oceanic processes create opportunities for the exchange of ], ]s, nutrients and marine life. | |||

| Most coral reefs exist in waters less than 50 m deep.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.marinebio.org/creatures/coral-reefs/ |title=Coral Reefs |website=marinebio.org |date=17 June 2018 |access-date=28 October 2022}}</ref> Some inhabit tropical continental shelves where cool, nutrient-rich ] does not occur, such as the ]. Others are found in the deep ocean surrounding islands or as atolls, such as in the ]. The reefs surrounding islands form when islands subside into the ocean, and atolls form when an island subsides below the surface of the sea. | |||

| Alternatively, Moyle and Cech distinguish six zones, though most reefs possess only some of the zones.<ref name=MoyleCech556>{{cite book |last1=Moyle |first1=Peter B. |url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=sZYWAQAAIAAJ}} |title=Fishes : an introduction to ichthyology |year=2004 |publisher=]/] |location=Upper Saddle River, N.J. |isbn=978-0-13-100847-2 |page=556 |edition=Fifth |first2=Joseph J. |last2=Cech}}</ref> | |||

| ]. The water waves at the left travel over the ''off-reef floor'' until they encounter the ''reef slope'' or ''fore reef''. Then the waves pass over the shallow ''reef crest''. When a wave enters shallow water it ], that is, it slows down and the wave height increases.]] | ]. The water waves at the left travel over the ''off-reef floor'' until they encounter the ''reef slope'' or ''fore reef''. Then the waves pass over the shallow ''reef crest''. When a wave enters shallow water it ], that is, it slows down and the wave height increases.]] | ||

| '''The reef surface''' is the shallowest part of the reef. It is subject to ] and ]s. When waves pass over shallow areas, they ], as shown in the adjacent diagram. This means the water is often agitated. These are the precise condition under which corals flourish. The light is sufficient for ] by the symbiotic zooxanthellae, and agitated water brings plankton to feed the coral. | |||

| '''The off-reef floor''' is the shallow sea floor surrounding a reef. This zone occurs next to reefs on continental shelves. Reefs around tropical islands and atolls drop abruptly to great depths and do not have such a floor. Usually sandy, the floor often supports ]s which are important foraging areas for reef fish. | |||

| '''The reef drop-off''' is, for its first 50 m, habitat for reef fish who find shelter on the cliff face and ] in the water nearby. The drop-off zone applies mainly to the reefs surrounding oceanic islands and atolls. | |||

| '''The reef face''' is the zone above the reef floor or the reef drop-off. This zone is often the reef's most diverse area. Coral and ] algae provide complex habitats and areas that offer protection, such as cracks and crevices. Invertebrates and ] algae provide much of the food for other organisms.<ref name=MoyleCech556 /> A common feature on this forereef zone is ]s that serve to transport sediment downslope. | |||

| '''The reef flat''' is the sandy-bottomed flat, which can be behind the main reef, containing chunks of coral. This zone may border a lagoon and serve as a protective area, or it may lie between the reef and the shore, and in this case is a flat, rocky area. Fish tend to prefer it when it is present.<ref name=MoyleCech556 /> | |||

| '''The reef lagoon''' is an entirely enclosed region, which creates an area less affected by wave action and often contains small reef patches.<ref name=MoyleCech556 /> | |||

| However, the |

However, the topography of coral reefs is constantly changing. Each reef is made up of irregular patches of algae, ] invertebrates, and bare rock and sand. The size, shape and relative abundance of these patches change from year to year in response to the various factors that favor one type of patch over another. Growing coral, for example, produces constant change in the fine structure of reefs. On a larger scale, tropical storms may knock out large sections of reef and cause boulders on sandy areas to move.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=] |date=March 24, 1978|volume=199 |issue=4335 |pages=1302–1310 |doi=10.1126/science.199.4335.1302 |title=Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs |first=Joseph H. |last=Connell |pmid=17840770 |bibcode=1978Sci...199.1302C}}</ref> | ||

| |journal=Science |date=March 24, 1978|volume=199 |issue=4335|pages=1302–1310 | |||

| |doi=10.1126/science.199.4335.1302 | |||

| |title=Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs | |||

| |first=Joseph H. |last=Connell | |||

| |pmid=17840770}}</ref> | |||

| ==Locations== | ==Locations== | ||

| {{anchor|Darwin Point}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]. Most corals live within this boundary. Note the cooler waters caused by upwelling on the southwest coast of Africa and off the coast of Peru.]] | |||

| ] | |||

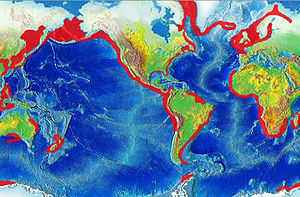

| ] in red. Coral reefs are not found in coastal areas where colder and nutrient-rich upwellings occur.]] | |||

| ]. Most corals live within this boundary. Note the cooler waters caused by upwelling on the southwest coast of Africa and off the coast of Peru.]] | |||

| ] in red. Coral reefs are not found in coastal areas where colder and nutrient-rich upwellings occur.]] | |||

| {{See also|List of reefs}} | |||

| Coral reefs are estimated to cover 284,300 km<sup>2</sup> (109,800 sq mi),<ref>] (2001) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110707004514/http://coral.unep.ch/atlaspr.htm |date=7 July 2011 }} Coral Reef Unit</ref> just under 0.1% of the oceans' surface area. The ] region (including the ], ], ] and the ]) account for 91.9% of this total. Southeast Asia accounts for 32.3% of that figure, while the Pacific including ] accounts for 40.8%. ] and ] coral reefs account for 7.6%.<ref name="Spalding">Spalding, Mark, Corinna Ravilious, and Edmund Green (2001). ''World Atlas of Coral Reefs''. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press and UNEP/WCMC {{ISBN|0520232550}}.</ref> | |||

| Although corals exist both in temperate and tropical waters, shallow-water reefs form only in a zone extending from approximately 30° N to 30° S of the equator. Tropical corals do not grow at depths of over {{convert|50|m|sp=us}}. The optimum temperature for most coral reefs is {{convert|26|–|27|C|F}}, and few reefs exist in waters below {{convert|18|C|F}}.<ref>Achituv, Y. and Dubinsky, Z. 1990. Evolution and Zoogeography of Coral Reefs Ecosystems of the World. Vol. 25:1–8.</ref> When the net production by reef building corals no longer keeps pace with relative sea level and the reef structure permanently drowns a '''Darwin Point''' is reached. One such point exists at the northwestern end of the Hawaiian Archipelago; see ].<ref>Grigg, R.W. (2011). Darwin Point. In: Hopley, D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2639-2_66</ref><ref>G. Flood, | |||

| Coral reefs are estimated to cover 284,300 km<sup>2</sup> (109,800 sq mi),<ref>] (2001) Coral Reef Unit</ref> just under 0.1% of the oceans' surface area. The ] region (including the ], ], ] and the ]) account for 91.9% of this total. Southeast Asia accounts for 32.3% of that figure, while the Pacific including ] accounts for 40.8%. ] and ] coral reefs account for 7.6%.<ref name="Spalding">Spalding, Mark, Corinna Ravilious, and Edmund Green. 2001. ''World Atlas of Coral Reefs''. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press and UNEP/WCMC.</ref> | |||

| The ‘Darwin Point’ of Pacific Ocean atolls and guyots: a reappraisal, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, Volume 175, Issues 1–4, 2001, Pages 147–152, ISSN 0031-0182, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00390-X.</ref> | |||

| However, reefs in the ] have adapted to temperatures of {{convert|13|C|F}} in winter and {{convert|38|C|F}} in summer.<ref name="Greenpeace"/> 37 species of scleractinian corals inhabit such an environment around ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Vajed Samiei|first=J.|author2=Dab K.|author3=Ghezellou P. |author4= Shirvani A. |title=Some Scleractinian Corals (Class: Anthozoa) of Larak Island, Persian Gulf|journal=Zootaxa|date=2013|volume=3636|issue=1|pages=101–143|doi=10.11646/zootaxa.3636.1.5|pmid=26042286}}</ref> | |||

| Although corals exist both in temperate and tropical waters, shallow-water reefs form only in a zone extending from 30° N to 30° S of the equator. Tropical corals do not grow at depths of over {{convert|50|m|sp=us}}. The optimum temperature for most coral reefs is {{convert|26|–|27|C|F}}, and few reefs exist in waters below {{convert|18|C|F}}.<ref>Achituv, Y. and Dubinsky, Z. 1990. Evolution and Zoogeography of Coral Reefs Ecosystems of the World. Vol. 25:1–8.</ref> However, reefs in the Persian Gulf have adapted to temperatures of {{convert|13|C|F}} in winter and {{convert|38|C|F}} in summer.<ref name="Greenpeace"/> | |||

| ] |

] inhabits greater depths and colder temperatures at much higher latitudes, as far north as Norway.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| |first=Johan Ernst |last=Gunnerus | |first=Johan Ernst |last=Gunnerus | ||

| | |

|author-link= Johan Ernst Gunnerus | ||

| |title= Om Nogle Norske Coraller | |title= Om Nogle Norske Coraller | ||

| |year=1768 | |year=1768 | ||

| }}</ref> Although deep water corals can form reefs, |

}}</ref> Although deep water corals can form reefs, little is known about them. | ||

| Coral reefs are rare along the ] and ] |

The ] on Earth is located near ], ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-08-05 |title=Coral reef in Eilat, the northernmost reef in the world, is growing |url=https://www.jpost.com/health-science/coral-reef-in-eilat-the-northernmost-reef-in-the-world-is-growing-564175 |access-date=2024-03-04 |website=The Jerusalem Post {{!}} JPost.com |language=en}}</ref> Coral reefs are rare along the west coasts of the ] and ], due primarily to ] and strong cold coastal currents that reduce water temperatures in these areas (the ], ], and ]s, respectively).<ref name="Nybakken">Nybakken, James. 1997. ''Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach.'' 4th ed. Menlo Park, CA: Addison Wesley.</ref> Corals are seldom found along the coastline of ]—from the eastern tip of India (]) to the ] and ] borders<ref name="Spalding" />—as well as along the coasts of northeastern ] and Bangladesh, due to the freshwater release from the ] and ] Rivers respectively. | ||

| Significant coral reefs include: | |||

| * The ]—largest, comprising over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over {{convert|2600|km|mi|sp=us}} off ] | * The ]—largest, comprising over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over {{convert|2600|km|mi|sp=us}} off ] | ||

| * The ]—second largest, stretching {{convert|1000|km|mi|sp=us}} from ] at the tip of the ] down to the ] | * The ]—second largest, stretching {{convert|1000|km|mi|sp=us}} from ] at the tip of the ] down to the ] | ||

| * The ]—second longest double barrier reef, covering {{convert|1500|km|sp=us}} | * The ]—second longest double barrier reef, covering {{convert|1500|km|sp=us}} | ||

| * The ] Barrier Reef—third largest, following the east coast of Andros Island, Bahamas, between ] and ] | * The ] Barrier Reef—third largest, following the east coast of Andros Island, Bahamas, between ] and ] | ||

| * The ]—includes |

* The ]—includes 6,000-year-old fringing reefs located along a {{convert|2000|km|mi|-1|abbr=on}} coastline | ||

| * The ]—largest continental US reef and the third-largest coral barrier reef, extends from ], located in ], to the ] in the Gulf of Mexico<ref>. Coris.noaa.gov (August 16, 2012). Retrieved on March 3, 2013.</ref> | |||

| * ] has the world's largest known ], comprising a 6.4 million acre reef that stretches from Miami to Charleston, S. C. Its discovery was announced in January 2024.<ref name="Sowers">{{cite journal |url= |title=Mapping and Geomorphic Characterization of the Vast Cold-Water Coral Mounds of the Blake Plateau |journal=Geomatics |doi=10.3390/geomatics4010002 |doi-access=free |date=January 12, 2024 |volume=4 |number=1 |pages=17–47 |last1=Sowers |first1=Derek C. |first2=Larry A. |last2=Mayer |first3=Giuseppe |last3=Masetti |first4=Erik |last4=Cordes |first5=Ryan |last5=Gasbarro |first6=Elizabeth |last6=Lobecker |first7=Kasey |last7=Cantwell |first8=Samuel |last8=Candio |first9=Shannon |last9=Hoy |first10=Mashkoor |last10=Malik |display-authors=etal}}</ref> | |||

| * ]—deepest photosynthetic coral reef, ] | * ]—deepest photosynthetic coral reef, ] | ||

| * Numerous reefs |

* Numerous reefs around the ] | ||

| * The ] coral reef area, the second-largest in Southeast Asia, is estimated at 26,000 square kilometres. 915 reef fish species and more than 400 scleractinian coral species, 12 of which are endemic are found there. | |||

| * The ] in ]'s ] province offer the highest known marine diversity.<ref>, Ultra Marine: In far eastern Indonesia, the Raja Ampat islands embrace a phenomenal coral wilderness, by David Doubilet, National Geographic, September 2007</ref> | |||

| * The ] in ]'s ] province offer the highest known marine diversity.<ref>, Ultra Marine: In far eastern Indonesia, the Raja Ampat islands embrace a phenomenal coral wilderness, by David Doubilet, National Geographic, September 2007</ref> | |||

| * ] is known for its northernmost coral reef system, located at {{Coord|32.4|N|64.8|W}}. The presence of coral reefs at this high latitude is due to the proximity of the ]. Bermuda coral species represent a subset of those found in the greater Caribbean.<ref>. Retrieved on May 28, 2015.</ref> | |||

| * The world's northernmost ] is located in the Finlayson Channel, in the inside passage of British Columbia, Canada.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://bc.ctvnews.ca/coral-reef-that-shouldn-t-exist-thrives-off-b-c-s-pacific-ocean-biologist-says-1.6804096#:~:text=%E2%80%9CLophelia%20reef%20is%20very%20important,other%20creatures%2C%20Du%20Preez%20said.| title = Coral reef that 'shouldn't exist' thrives off B.C.'s coast in Pacific Ocean, biologist says| last = Shen| first = Nono| date = 12 March 2024| website = CTV News| publisher = The Canadian Press| access-date = 13 March 2024| quote =}}</ref> | |||

| * The world's southernmost coral reef is at ], in the Pacific Ocean off the east coast of Australia. | |||

| == |

==Coral== | ||

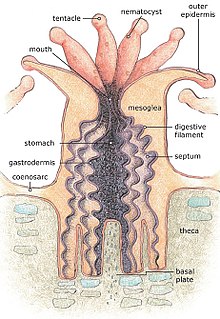

| ] | ] ] anatomy]] | ||

| {{ |

{{main|Coral}} | ||

| When alive, corals are ] of small animals embedded in ] shells. Coral heads consist of accumulations of individual animals called ]s, arranged in diverse shapes.<ref>{{cite thesis |degree=Ph.D. |author=Sherman, C.D.H. |year=2006 |url=http://www.library.uow.edu.au/adt-NWU/uploads/approved/adt-NWU20060726.114643/public/02Whole.pdf |title=The Importance of Fine-scale Environmental Heterogeneity in Determining Levels of Genotypic Diversity and Local Adaption |publisher=University of Wollongong |access-date=7 June 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080724113051/http://www.library.uow.edu.au/adt-NWU/uploads/approved/adt-NWU20060726.114643/public/02Whole.pdf |archive-date=24 July 2008}}</ref> Polyps are usually tiny, but they can range in size from a pinhead to {{convert|12|in|cm|sp=us}} across. | |||

| Reef-building or ]s live only in the ] (above |

Reef-building or ]s live only in the ] (above 70 m), the depth to which sufficient sunlight penetrates the water.<ref>{{Cite web |publisher=National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |work=Coral Reef Information System (CoRIS) |title=What are Coral Reefs |url=https://www.coris.noaa.gov/about/what_are/ |access-date=2022-11-09}}</ref> | ||

| | coauthors =Marshall, Paul; Schuttenberg, Heidi. | |||

| | title =A Reef Manager’s Guide to Coral Bleaching | |||

| | publisher = ], | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | location =Townsville, Australia | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | url =http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/corp_site/info_services/publications/misc_pub/a_reef_managers_guide_to_coral_bleaching | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | isbn = 1-876945-40-0 | |||

| | author =Paul Marshall and Heidi Schuttenberg. }}</ref> | |||

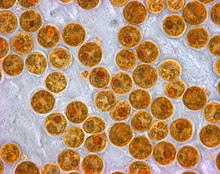

| ===Zooxanthellae=== | |||

| Reefs grow as polyps and other organisms deposit calcium carbonate,<ref>Stacy, J., Marion, G., McCulloch, M. and Hoegh-Guldberg, O. "." ''University of Queensland – Centre for Marine Studies.'' May 2007. Accessed 2009-06-07.</ref><ref>Nothdurft, L.D. "." ''Queensland University of Technology Ph.D. Thesis.'' 2007. Accessed 2009-06-07.</ref> the basis of coral, as a skeletal structure beneath and around themselves, pushing the coral head's top upwards and outwards.<ref>Wilson, R.A. "."''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.'' August 9, 2007. Accessed 2009-06-07.</ref> Waves, grazing fish (such as ]), ]s, ], and other forces and organisms act as ], breaking down coral skeletons into fragments that settle into spaces in the reef structure or form sandy bottoms in associated reef lagoons. Many other organisms living in the reef community contribute skeletal calcium carbonate in the same manner.<ref>Jennings S, Kaiser MJ and Reynolds JD (2001) Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-0-632-05098-7.</ref> ] are important contributors to reef structure in those parts of the reef subjected to the greatest forces by waves (such as the reef front facing the open ocean). These algae strengthen the reef structure by depositing limestone in sheets over the reef surface. | |||

| ], the microscopic algae that lives inside coral, gives it colour and provides it with food through photosynthesis]] | |||

| Coral polyps do not photosynthesize, but have a symbiotic relationship with microscopic ] (]s) of the genus '']'', commonly referred to as ]. These organisms live within the polyps' tissues and provide organic nutrients that nourish the polyp in the form of ], ] and ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200528115104/https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/corals/coral02_zooxanthellae.html |date=28 May 2020 }}. Oceanservice.noaa.gov (March 25, 2008). Retrieved on November 1, 2011.</ref> Because of this relationship, coral reefs grow much faster in clear water, which admits more sunlight. Without their symbionts, coral growth would be too slow to form significant reef structures. Corals get up to 90% of their nutrients from their symbionts.<ref name="GuideCoralBleaching" /> In return, as an example of ], the corals shelter the zooxanthellae, averaging one million for every cubic centimetre of coral, and provide a constant supply of the ] they need for photosynthesis. | |||

| ] | |||

| The colonies of the one thousand coral ] assume a characteristic shape such as ], cabbages, ], ], wire strands and ].{{citation needed|date=December 2010}} | |||

| The varying pigments in different species of zooxanthellae give them an overall brown or golden-brown appearance and give brown corals their colors. Other pigments such as reds, blues, greens, etc. come from colored proteins made by the coral animals. Coral that loses a large fraction of its zooxanthellae becomes white (or sometimes pastel shades in corals that are pigmented with their own proteins) and is said to be ], a condition which, unless corrected, can kill the coral. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| There are eight ]s of ''Symbiodinium'' ]s. Most research has been conducted on clades A–D. Each clade contributes their own benefits as well as less compatible attributes to the survival of their coral hosts. Each photosynthetic organism has a specific level of sensitivity to photodamage to compounds needed for survival, such as proteins. Rates of regeneration and replication determine the organism's ability to survive. Phylotype A is found more in the shallow waters. It is able to produce ]s that are ], using a derivative of ] to absorb the UV radiation and allowing them to better adapt to warmer water temperatures. In the event of UV or thermal damage, if and when repair occurs, it will increase the likelihood of survival of the host and symbiont. This leads to the idea that, evolutionarily, clade A is more UV resistant and thermally resistant than the other clades.<ref name="Reynolds">{{cite journal|vauthors=Reynolds J, Bruns B, Fitt W, Schmidt G|year=2008|title=Enhanced photoprotection pathways in symbiotic dinoflagellates of shallow-water corals and other cnidarians|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=105|issue=36|pages=13674–13678|bibcode=2008PNAS..10513674R|doi=10.1073/pnas.0805187105|pmid=18757737|pmc=2527352|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Corals reproduce both sexually and asexually. An individual polyp uses both reproductive modes within its lifetime. Corals reproduce sexually by either internal or external fertilization. The reproductive cells are found on the ] membranes that radiate inward from the layer of tissue that lines the stomach cavity. Some mature adult corals are hermaphroditic; others are exclusively male or female. A few ] change sex as they grow. | |||

| Clades B and C are found more frequently in deeper water, which may explain their higher vulnerability to increased temperatures. Terrestrial plants that receive less sunlight because they are found in the undergrowth are analogous to clades B, C, and D. Since clades B through D are found at deeper depths, they require an elevated light absorption rate to be able to synthesize as much energy. With elevated absorption rates at UV wavelengths, these phylotypes are more prone to coral bleaching versus the shallow clade A. | |||

| Internally fertilized eggs develop in the polyp for a period ranging from days to weeks. Subsequent development produces a tiny ], known as a ]. Externally fertilized eggs develop during synchronized spawning. Polyps release eggs and sperm into the water en masse, simultaneously. Eggs disperse over a large area. The timing of spawning depends on time of year, water temperature, and tidal and lunar cycles. Spawning is most successful when there is little variation between high and low ]. The less water movement, the better the chance for fertilization. Ideal timing occurs in the spring. Release of eggs or planula usually occurs at night, and is sometimes in phase with the lunar cycle (three to six days after a full moon). The period from release to settlement lasts only a few days, but some planulae can survive afloat for several weeks. They are vulnerable to predation and environmental conditions. The lucky few planulae which successfully attach to substrate next confront competition for food and space.{{citation needed|date=December 2010}} | |||

| Clade D has been observed to be high temperature-tolerant, and has a higher rate of survival than clades B and C during modern ].<ref name="Reynolds" /> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:Brain coral.jpg|] | |||

| ===Skeleton=== | |||

| File:Staghorn-coral-1.jpg|] | |||

| ] sp.'']] | |||

| Reefs grow as polyps and other organisms deposit calcium carbonate,<ref>{{cite web |vauthors=Stacy J, Marion G, McCulloch M, Hoegh-Guldberg O |title=Long-term changes to Mackay Whitsunday water quality and connectivity between terrestrial, mangrove and coral reef ecosystems: Clues from coral proxies and remote sensing records |series=Synthesis of research from an ARC Linkage Grant (2004–2007) |url-status=dead |publisher=University of Queensland |department=Centre for Marine Studies |date=May 2007 |url=http://www.marine.uq.edu.au/mackayarc/Reports%20&%20publications/Mackay_ARC_2007_lowres.pdf |access-date=7 June 2009 |archive-date=August 30, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070830013615/http://marine.uq.edu.au/mackayarc/Reports%20%26%20publications/Mackay_ARC_2007_lowres.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite thesis |last=Nothdurft |first=Luke D. |url=https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16690/1/Luke_D._Nothdurft_Thesis.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110309095832/https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16690/1/Luke_D._Nothdurft_Thesis.pdf |archive-date=2011-03-09 |url-status=live |title=Microstructure and early diagenesis of recent reef building scleractinian corals, Heron reef, Great Barrier Reef: implications for paleoclimate analysis |publisher=Queensland University of Technology |degree=Ph.D. |date=2007 |publication-date=2008 |access-date=2022-11-10 |via=}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221111063847/https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16690/ |date=11 November 2022 }}</ref> the basis of coral, as a skeletal structure beneath and around themselves, pushing the coral head's top upwards and outwards.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |vauthors=Wilson RA |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/biology-individual/ |article=The Biological Notion of Individual |title=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |date=9 August 2007 |access-date=7 June 2009}}</ref> Waves, grazing fish (such as ]), ]s, ] and other forces and organisms act as ], breaking down coral skeletons into fragments that settle into spaces in the reef structure or form sandy bottoms in associated reef lagoons. | |||

| Typical shapes for coral ] are named by their resemblance to terrestrial objects such as ], cabbages, ], ], wire strands and ]. These shapes can depend on the life history of the coral, like light exposure and wave action,<ref>{{cite journal |last=Chappell |first=John |title=Coral morphology, diversity and reef growth |journal=Nature |date=17 July 1980 |volume=286 |issue=5770 |pages=249–252 |doi=10.1038/286249a0 |bibcode=1980Natur.286..249C |s2cid=4347930 }}</ref> and events such as breakages.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Jackson |first=Jeremy B. C. |title=Adaptation and Diversity of Reef Corals |journal=BioScience |date=1 July 1991 |volume=41 |issue=7 |pages=475–482 |doi=10.2307/1311805 |jstor=1311805}}</ref> | |||

| {{clear left}} | |||

| ===Reproduction=== | |||

| ] and attached to the ocean floor. But unlike plants, corals do not make their own food.<ref> ''NOAA: National Ocean Service''. Accessed 11 February 2020. Updated: 7 January 2020.</ref>]] | |||

| {{external media | width = 210px | float = right | headerimage= ] | video1 = , Tom Shlesinger, Sep 5, 2019.}} | |||

| Corals reproduce both sexually and asexually. An individual polyp uses both reproductive modes within its lifetime. Corals reproduce sexually by either internal or external fertilization. The reproductive cells are found on the ], membranes that radiate inward from the layer of tissue that lines the stomach cavity. Some mature adult corals are hermaphroditic; others are exclusively male or female. A few ] change sex as they grow. | |||

| Internally fertilized eggs develop in the polyp for a period ranging from days to weeks. Subsequent development produces a tiny ], known as a ]. Externally fertilized eggs develop during synchronized spawning. Polyps across a reef simultaneously release eggs and sperm into the water en masse. Spawn disperse over a large area. The timing of spawning depends on time of year, water temperature, and tidal and lunar cycles. Spawning is most successful given little variation between high and low ]. The less water movement, the better the chance for fertilization. The release of eggs or planula usually occurs at night and is sometimes in phase with the lunar cycle (three to six days after a full moon).<ref name="Markandeya">{{cite journal |last1=Markandeya |first1=Virat |title=How lunar cycles guide the spawning of corals, worms and more |journal=Knowable Magazine |publisher= Annual Reviews |date=22 February 2023 |doi=10.1146/knowable-022223-2 |doi-access=free |url=https://knowablemagazine.org/article/living-world/2023/lunar-cycles-guide-spawning |access-date=6 March 2023 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="Häfker">{{cite journal |last1=Häfker |first1=N. Sören |last2=Andreatta |first2=Gabriele |last3=Manzotti |first3=Alessandro |last4=Falciatore |first4=Angela |last5=Raible |first5=Florian |last6=Tessmar-Raible |first6=Kristin |title=Rhythms and Clocks in Marine Organisms |journal=Annual Review of Marine Science |date=16 January 2023 |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=509–538 |doi=10.1146/annurev-marine-030422-113038 |pmid=36028229 |bibcode=2023ARMS...15..509H |s2cid=251865474 |language=en |issn=1941-1405|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Lin">{{cite journal |last1=Lin |first1=Che-Hung |last2=Takahashi |first2=Shunichi |last3=Mulla |first3=Aziz J. |last4=Nozawa |first4=Yoko |title=Moonrise timing is key for synchronized spawning in coral Dipsastraea speciosa |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |date=24 August 2021 |volume=118 |issue=34 |pages=e2101985118 |doi=10.1073/pnas.2101985118 |pmid=34373318 |pmc=8403928 |bibcode=2021PNAS..11801985L |language=en |issn=0027-8424 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The period from release to settlement lasts only a few days, but some planulae can survive afloat for several weeks. During this process, the larvae may use several different cues to find a suitable location for settlement. At long distances sounds from existing reefs are likely important,<ref name="Vermeij 2010">{{cite journal |last1=Vermeij |first1=Mark J. A. |last2=Marhaver |first2=Kristen L. |last3=Huijbers |first3=Chantal M. |last4=Nagelkerken |first4=Ivan |last5=Simpson |first5=Stephen D. |title=Coral larvae move toward reef sounds |journal=PLOS ONE |date=2010 |volume=5 |issue=5 |pages=e10660 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0010660|pmid=20498831 |doi-access=free |pmc=2871043 |bibcode=2010PLoSO...510660V }}</ref> while at short distances chemical compounds become important.<ref name="Gleason 2009">{{cite journal |last1=Gleason |first1=D. F. |last2=Danilowicz |first2=B. S. |last3=Nolan |first3=C. J. |title=Reef waters stimulate substratum exploration in planulae from brooding Caribbean corals |journal=Coral Reefs |date=2009 |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=549–554 |doi=10.1007/s00338-009-0480-1|bibcode=2009CorRe..28..549G |s2cid=39726375 }}</ref> The larvae are vulnerable to predation and environmental conditions. The lucky few planulae that successfully attach to substrate then compete for food and space.{{citation needed|date=December 2010}} | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==Gallery of reef-building corals== | |||

| {| | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=550px | <gallery mode="packed"> | |||

| File:Fluorescent coral - MBA - DSC07089.JPG|Fluorescent coral<ref>{{cite web|url=http://photography.nationalgeographic.com/wallpaper/photography/photos/coral-kingdoms/fluorescent-coral-laman/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100629212418/http://photography.nationalgeographic.com/wallpaper/photography/photos/coral-kingdoms/fluorescent-coral-laman |url-status=dead |archive-date=29 June 2010 |title=Fluorescent coral |publisher=National Geographic Society|department=photography|series=Coral kingdoms}}</ref> | |||

| File:Cirripathes sp (Spiral Wire Coral).jpg|Spiral wire coral | File:Cirripathes sp (Spiral Wire Coral).jpg|Spiral wire coral | ||

| File:Muchroom coral.JPG|] | |||

| File:Staghorn-coral-1.jpg|] | |||

| File:PillarCoral.jpg|] | File:PillarCoral.jpg|] | ||

| File:Brain coral.jpg|] | |||

| File:Meandrina meandrites (Maze Coral).jpg|] | |||

| File:Black coral.jpg|] | |||

| File:Elkhorn Coral with a Yellowtail Damselfish in the Caribbean Sea in Curaçao.jpg|] | |||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| | <gallery mode="packed" heights="400"> | |||

| File:Fluorescent Coral Movie.gif|{{center|Fluorescent coral}} | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| |} | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==Other reef builders== | |||

| ] are the most prodigious reef-builders. However many other organisms living in the reef community contribute skeletal calcium carbonate in the same manner as corals. These include ], ] and ]s.<ref>{{cite book |vauthors=Jennings S, Kaiser MJ, Reynolds JD |year=2001 |url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=oTVyeNQyoiMC}}|title=Marine Fisheries Ecology |pages=291–293 |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |isbn=978-0-632-05098-7}}</ref> Reefs are always built by the combined efforts of these different ], with different organisms leading reef-building in different ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kuznetsov |first1=Vitaly |title=The evolution of reef structures through time: Importance of tectonic and biological controls |journal=Facies |date=1 December 1990 |volume=22 |issue=1 |pages=159–168 |doi=10.1007/BF02536950|bibcode=1990Faci...22..159K |s2cid=127193540 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Coralline algae=== | |||

| {{main|Coralline algae}} | |||

| {{See also|Coralline rock}} | |||

| ] ''] sp.'']] | |||

| ] are important contributors to reef structure. Although their mineral deposition rates are much slower than corals, they are more tolerant of rough wave-action, and so help to create a protective crust over those parts of the reef subjected to the greatest forces by waves, such as the reef front facing the open ocean. They also strengthen the reef structure by depositing limestone in sheets over the reef surface.{{citation needed |date=June 2018}} | |||

| ===Sponges=== | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{main|Sponge reef}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| "]" is the descriptive name for all ] that build ]. In the early ], ] were the world's first reef-building organisms, and sponges were the only reef-builders until the ]. ]s still assist corals building modern reefs, but like ] are much slower-growing than corals and their contribution is (usually) minor.{{citation needed |date=June 2018}} | |||

| In the northern Pacific Ocean ]s still create deep-water mineral-structures without corals, although the structures are not recognizable from the surface like tropical reefs. They are the only ] organisms known to build reef-like structures in cold water.{{citation needed |date=June 2018}} | |||

| ===Bivalves=== | |||

| {{See also|Bivalve reef}} | |||

| ]s (''Crassostrea virginica'')]] | |||

| ]s are dense aggregations of ]s living in colonial communities. Other regionally-specific names for these structures include oyster beds and oyster banks. Oyster larvae require a hard substrate or surface to attach on, which includes the shells of old or dead oysters. Thus reefs can build up over time as new larvae settle on older individuals. '']'' were once abundant in ] and shorelines bordering the ] until the late nineteenth century.<ref>Newell, R.I.E. 1988. Ecological changes in Chesapeake Bay: are they the results of ] the American oyster, ''Crassostrea virginica''? In: M. Lynch and E.C. Krome (eds.) Understanding the estuary: advances in Chesapeake Bay research, Chesapeake Research Consortium, Solomons MD pp.536–546.</ref> '']'' is a species of flat oyster that had also formed large reefs in South Australia.<ref name=good>{{cite web |title=4 things you might not know about South Australia's new shellfish reef |website=Government of South Australia. ] |date=10 May 2019 |url=https://www.environment.sa.gov.au/goodliving/posts/2019/05/windara-reef |access-date=28 February 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Hippuritida, an extinct order of bivalves known as ], were major reef-building organisms during the ]. By the mid-Cretaceous, rudists became the dominant tropical reef-builders, becoming more numerous than scleractinian corals. During this period, ocean temperatures and saline levels—which corals are sensitive to—were higher than it is today, which may have contributed to the success of rudist reefs.<ref name=Johnson_2002>{{cite journal |author=Johnson, C. |year=2002 |title=The rise and fall of Rudist reefs |journal=American Scientist |volume=90 |issue=2 |page=148 |doi=10.1511/2002.2.148 |bibcode=2002AmSci..90..148J |s2cid=121693025 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Gastropods=== | |||

| Some gastropods, like family ], are sessile and cement themselves to the substrate, contributing to the reef building.<ref>{{cite journal | url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031018208003672 | doi=10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.06.008 | title=Vermetid reefs and their use as palaeobathymetric markers: New insights from the Late Miocene of the Mediterranean (Southern Italy, Crete) | journal=Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology | date=19 September 2008 | volume=267 | issue=1 | pages=89–101 | last1=Vescogni | first1=Alessandro | last2=Bosellini | first2=Francesca R. | last3=Reuter | first3=Markus | last4=Brachert | first4=Thomas C. | bibcode=2008PPP...267...89V }}</ref> | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==Darwin's paradox== | ==Darwin's paradox== | ||

| {{Quote box | {{Quote box | ||

| | style= width: |

| style = width:270px; | ||

| | border = 1px | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | bgcolor = #ffffff | |||

| |quote= |

| quote = {{center|'''Darwin's paradox'''}}"Coral... seems to proliferate when ocean waters are warm, poor, clear and agitated, a fact which Darwin had already noted when he passed through Tahiti in 1842. This constitutes a fundamental paradox, shown quantitatively by the apparent impossibility of balancing input and output of the nutritive elements which control the coral polyp metabolism. | ||

| This constitutes a fundamental paradox, shown quantitatively by the apparent impossibility of balancing input and output of the nutritive elements which control the coral polyp metabolism. | |||

| Recent oceanographic research has brought to light the reality of this paradox by confirming that the ] of the ocean ] zone persists right up to the swell-battered reef crest. When you approach the reef edges and atolls from the quasidesert of the open sea, the near absence of living matter suddenly becomes a plethora of life, without transition. So why is there something rather than nothing, and more precisely, where do the necessary nutrients for the functioning of this extraordinary coral reef machine come from |

Recent oceanographic research has brought to light the reality of this paradox by confirming that the ] of the ocean ] zone persists right up to the swell-battered reef crest. When you approach the reef edges and atolls from the quasidesert of the open sea, the near absence of living matter suddenly becomes a plethora of life, without transition. So why is there something rather than nothing, and more precisely, where do the necessary nutrients for the functioning of this extraordinary coral reef machine come from?" | ||

| — Francis Rougerie<ref>Rougerier, F ''ORSTOM'', Papeete.</ref> |