| Revision as of 23:54, 4 January 2012 view sourceLLTimes (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,561 edits →Strategic importance← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:31, 24 December 2024 view source Project Termina (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users791 edits →Geography: typosTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (705 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Region in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Kashmir administered by China}} | |||

| {{Coord|35|7|N|79|8|E|display=title}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Too few opinions|discuss=Talk:Sino-Indian War#Sources|date=September 2017}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=October 2019}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| | name = Aksai Chin | |||

| | type = Territory administered by China | |||

| | other_name = Aksayqin | |||

| | image_skyline = 甜水海兵站.jpg | |||

| | image_caption = Sign of a ] service station in ], Aksai Chin | |||

| | image_map = File:Kashmir region. LOC 2003626427 - showing sub-regions administered by different countries.jpg | |||

| | map_alt = Map of the disputed Kashmir region showing areas of control by India, Pakistan, and China | |||

| | map_caption = A map of the disputed ] region showing the Chinese-administered territory of Aksai Chin in brown<ref name=tertiary-kashmir/> | |||

| | image_map1 = {{maplink|frame=yes|plain=yes|frame-width=300|frame-height=170|frame-align=center|zoom=4|type=point|title=Aksai Chin|marker=city|type2=shape|stroke-width2=2|stroke-color2=#808080}} | |||

| | map_caption1 = Interactive map of Aksai Chin | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|35.0|N|79.0|E|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 38000 | |||

| | subdivision_type = Country | |||

| | subdivision_name = * ] (administered by) | |||

| * ] (claimed by) | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] or ] | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = * ], ], ] | |||

| * ], ], ] | |||

| * ], ] ] (claimed) | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Aksai Chin''' is a region administered by ] partly in ], ], ]<ref name="cihai"/> and partly in ], ], ] and constituting the easternmost portion of the larger ] region that has been the subject of a dispute between India and China since 1959.<ref name=tertiary-kashmir> The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of ] and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the ] (a) through (e), reflecting ] in the coverage. Although "controlled" and "held" are also applied neutrally to the names of the disputants or to the regions administered by them, as evidenced in sources (h) through (i) below, "held" is also considered politicized usage, as is the term "occupied," (see (j) below). <br/> | |||

| (a) {{citation|title=Kashmir, region Indian subcontinent|publisher=Encyclopaedia Britannica|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Kashmir-region-Indian-subcontinent |accessdate=15 August 2019}} (subscription required) Quote: "Kashmir, region of the northwestern Indian subcontinent ... has been the subject of dispute between India and Pakistan since the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. The northern and western portions are administered by Pakistan and comprise three areas: Azad Kashmir, Gilgit, and Baltistan, the last two being part of a territory called the Northern Areas. Administered by India are the southern and southeastern portions, which constitute the state of Jammu and Kashmir but are slated to be split into two union territories.";<br/> (b) {{citation|last1=Pletcher|first1=Kenneth|title=Aksai Chin, Plateau Region, Asia|publisher=Encyclopaedia Britannica|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Aksai-Chin |accessdate=16 August 2019}} (subscription required) Quote: "Aksai Chin, Chinese (Pinyin) Aksayqin, portion of the Kashmir region, at the northernmost extent of the Indian subcontinent in south-central Asia. It constitutes nearly all the territory of the Chinese-administered sector of Kashmir that is claimed by India to be part of the Ladakh area of Jammu and Kashmir state."; <br/> (c) {{citation|chapter=Kashmir|title=Encyclopedia Americana|publisher=Scholastic Library Publishing|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=l_cWAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA328|year=2006|isbn=978-0-7172-0139-6|page=328}} C. E Bosworth, University of Manchester Quote: "KASHMIR, kash'mer, the northernmost region of the Indian subcontinent, administered partlv by India, partly by Pakistan, and partly by China. The region has been the subject of a bitter dispute between India and Pakistan since they became independent in 1947"; <br/> (d) {{citation|last1=Osmańczyk|first1=Edmund Jan|title=Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fSIMXHMdfkkC&pg=PA1191|year=2003|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-0-415-93922-5|pages=1191–}} Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir: Territory in northwestern India, subject to a dispute between India and Pakistan. It has borders with Pakistan and China." <br/>(e) {{citation|last=Talbot|first=Ian|title=A History of Modern South Asia: Politics, States, Diasporas|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eNg_CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA28|year=2016|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0-300-19694-8|pages=28–29}} Quote: "We move from a disputed international border to a dotted line on the map that represents a military border not recognized in international law. The line of control separates the Indian and Pakistani administered areas of the former Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir."; <br/> (f) {{citation|last=Skutsch|first=Carl|editor-last=Ciment|editor-first=James|title=Encyclopedia of Conflicts Since World War II|edition=2nd|year=2015|orig-year=2007|isbn=978-0-7656-8005-1|chapter=China: Border War with India, 1962|location=London and New York|publisher=Routledge|page=573|quote=The situation between the two nations was complicated by the 1957–1959 uprising by Tibetans against Chinese rule. Refugees poured across the Indian border, and the Indian public was outraged. Any compromise with China on the border issue became impossible. Similarly, China was offended that India had given political asylum to the Dalai Lama when he fled across the border in March 1959. In late 1959, there were shots fired between border patrols operating along both the ill-defined McMahon Line and in the Aksai Chin.}}<br/> (g) {{citation|last=Clary|first=Christopher|year=2022|title=The Difficult Politics of Peace: Rivalry in Modern South Asia|publisher=Oxford University Press|location = Oxford and New York|isbn=9780197638408|page=109|quote=Territorial Dispute: The situation along the Sino-Indian frontier continued to worsen. In late July (1959), an Indian reconnaissance patrol was blocked, "apprehended," and eventually expelled after three weeks in custody at the hands of a larger Chinese force near Khurnak Fort in Aksai Chin. ... Circumstances worsened further in October 1959, when a major class at Kongka Pass in eastern Ladakh led to nine dead and ten captured Indian border personnel, making it by far the most serious Sino-Indian class since India's independence.}} <br/> (h) {{citation|last=Bose|first=Sumantra|title=Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3ACMe9WBdNAC&pg=PA294|year=2009|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-02855-5|pages=294, 291, 293}} Quote: "J&K: Jammu and Kashmir. The former princely state that is the subject of the Kashmir dispute. Besides IJK (Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir. The larger and more populous part of the former princely state. It has a population of slightly over 10 million, and comprises three regions: Kashmir Valley, Jammu, and Ladakh.) and AJK ('Azad" (Free) Jammu and Kashmir. The more populous part of Pakistani-controlled J&K, with a population of approximately 2.5 million.), it includes the sparsely populated "Northern Areas" of Gilgit and Baltistan, remote mountainous regions which are directly administered, unlike AJK, by the Pakistani central authorities, and some high-altitude uninhabitable tracts under Chinese control." <br/> (i) {{citation|last=Fisher|first=Michael H.|title=An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kZVuDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA166|year=2018|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-11162-2|page=166}} Quote: "Kashmir’s identity remains hotly disputed with a UN-supervised “Line of Control” still separating Pakistani-held Azad (“Free”) Kashmir from Indian-held Kashmir."; <br/> (j) {{citation|last=Snedden|first=Christopher|title=Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5amKCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA10|year=2015|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-1-84904-621-3|page=10}} Quote:"Some politicised terms also are used to describe parts of J&K. These terms include the words 'occupied' and 'held'."</ref> It is claimed by ] as part of its ], ] ]. | |||

| '''Aksai Chin''' ({{lang-hi|अक्साई चिन}}; ]: اکسائی چن; {{zh|c=阿克赛钦|p=Ākèsàiqīn}}) is one of the two main disputed border areas between ] and ], and the other is the area in the ] which the Chinese call ], which comprises most of India's ]. It is administered by China as part of ] in the ] of ], but is also claimed by India as a part of the ] district of the state of ]. What little evidence exists suggests that the few true locals in Aksai Chin have ] beliefs. Place names like inter alia Sumnal, Palong Karpo , Thaldat, Sumgal, Nischu, Sumna, Sumdo in Aksai Chin are all place names in Aksai Chin of Ladakhi or Tibetan origin. In 1962 China and India fought a ] over Aksai Chin and Parts of ], and the Parliament of India on November 14, 1962 passed a unanimous resolution vowing to recover every inch of land occupied by China “howsoever long or hard the struggle may be” which remains to be fulfilled. In 1993 and 1996 the two countries signed agreements to respect the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/india-china_conflicts.htm |title=India-China Border Dispute |publisher=GlobalSecurity.org}}</ref> | |||

| ==Name== | ==Name== | ||

| Aksai Chin was first mentioned by Muhammad Amin, the ]i guide of the ], who were contracted in 1854 by the British ] to explore Central Asia. Amin explained its meaning as "the great white sand desert".<ref name="van Driem">{{cite book |first=George L. van |last=Driem |date=25 May 2021 |title=Ethnolinguistic Prehistory: The Peopling of the World from the Perspective of Language, Genes and Material Culture |publisher=BRILL |page=53 |isbn=978-90-04-44837-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6EswEAAAQBAJ}}</ref> Linguist ] states that the name intended by Amin was ''Aqsai Chöl'' ({{langx|ug|ﺋﺎﻗﺴﺎﻱ چۆل}}; {{lang-cyrl|ақсай чөл}}) which could mean "white ravine desert" or "white coomb desert". The word '']'' for desert seems to have been corrupted in English transliteration into "chin".<ref name="van Driem"/> | |||

| The etymology of Aksai Chin is uncertain regarding the word "Chin". As a word of Turk origin, ''aksai'' literally means "white brook" but whether the word ''Chin'' refers to ''Chinese'' or ''pass'' is disputed. The area is largely a vast high-altitude ] including some ] from {{convert|4800|m|ft}} to {{convert|5500|m|ft}} above sea level. It covers an area of {{convert|37244|km2|sqmi}}. The Chinese name of the region, 阿克赛钦, is composed of ] chosen for their phonetic values,<ref>All these characters can be seen in Chinese Misplaced Pages's ], which in its turn is based on the standard ] guide, ] (The Great Dictionary of Foreign Personal Names' Translations), 1993, ISBN 7-5001-0221-6(first edition); 1997, ISBN 7-5001-0799-4 (revised edition)</ref> irrespective of their meaning. | |||

| Some sources have interpreted ''Aksai'' to have the ] meaning "white stone desert", including several British colonial,<ref name="british_india_1862">{{cite book |author=Government of Punjab |title=Report on the Trade and Resources of the Countries on the North-western Boundary of British India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4GEOAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA1-PR21 |year=1862 |publisher=Government Press |location=Lahore |pages=xxii. c |quote=the "Aksai Chin," or as the term implies the great Chinese white desert or plain.}}</ref><ref name="asiatic_society">{{cite book |title=Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ma8IAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA1-PA50 |year=1868 |publisher=Bishop's College Press |page=50 |quote=the Akzai Chin or White Desert}}</ref> modern Western,<ref name="Kaminsky">{{cite book |last1=Kaminsky |first1=Arnold P. |last2=Long |first2=Roger D. |title=India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VVxlfDHGTFYC&pg=PA23 |date=23 September 2011 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0-313-37463-0 |page=23 |quote=Aksai Chin (as Uyghur name meaning "desert of white stones") |access-date=11 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200405051052/https://books.google.com/books?id=VVxlfDHGTFYC&pg=PA23 |archive-date=5 April 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="naval_war_college">{{cite book |title=Naval War College Review |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jFpCNsIhNQQC&pg=PP106 |year=1966 |publisher=Naval War College |page=98 |quote=During these same months, the route across the portion of Ladakh known as Aksai Chin (white stone desert) is highly traversable.}}</ref><ref name="HedinAmbolt1967">{{cite book |author1=Sven Anders Hedin |author2=Nils Peter Ambolt |title=Central Asia Atlas, Memoir on Maps: Index of geographical names, by D.M. Farquhar, G. Jarring and E. Norin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wiHxAAAAMAAJ |year=1967 |publisher=Sven Hedin Foundation, Statens etnografiska museum |page=12 |quote=Aksai Chin, region between the K'unlun main range and the Loqzung Mountains: T. eq say 'white gravelly plain' + cin '(of) China' (Cin, earliest designation by which China was known in Central Asia).}}</ref><ref name="Lintner2018">{{cite book |author=Bertil Lintner |title=China's India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-L9DDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT85 |date=25 January 2018 |publisher=OUP India |isbn=978-0-19-909163-8 |pages=85 |quote=The name Aksai Chin means 'the desert of white stones'}}</ref> Chinese,<ref name="cihai">{{cite book |editor1=夏征农 |editor2=陈至立 |script-title=zh:辞海:第六版彩图本 |trans-title=] (Sixth Edition in Color) |date=September 2009 |location=上海. ] |publisher=上海辞书出版社. ]. |isbn=9787532628599 |language=zh |page=0008 |quote={{lang|zh-hans|'''阿克赛钦''' 地名区。维吾尔语意即"中国的白石滩"。在新疆维吾尔自治区和田县南部、喀喇昆仑山和昆仑山间。}}}}</ref><ref name="gongbao">{{cite journal |journal={{lang|zh-hans|]}} (Bulletin of the State Council of PRC) |url=http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/shuju/1962/gwyb196212.pdf |script-title=zh:国务院总理周恩来就中印边界問題致亚非国家領导人的信 |language=zh |date=15 November 1962 |access-date=30 December 2019 |author=] (Chou En-Lai) |quote={{lang|zh-hans|在西段,印度政府提出爭議的传统习惯綫以东和以北的地区,历来是屬于中国的。这个地区主要包括中国新疆所屬的阿克賽欽地区和西藏阿里地区的一部分,面积共为三万三千平方公里,相当于一个比利时或三个黎巴嫩。这个地区虽然人烟稀少,却历来是联結新疆和西藏阿里的交通命脉。新疆的柯尔克孜族和維吾尔族的牧民經常在这一带放牧。阿克賽欽这个地名就是維吾尔語“中国的白石滩”的意思。这块地方一直到現在是在中国的管轄之下。}} |page=228 |via={{lang|zh-hans|]}} |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150613165705/http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/shuju/1962/gwyb196212.pdf |archive-date=13 June 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> and Indian sources.<ref name="Kler1995">{{cite book |author=Gurdip Singh Kler |title=Unsung Battles of 1962 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hciHTVUILb4C&pg=PA156 |year=1995 |publisher=Lancer Publishers |isbn=978-1-897829-09-7 |page=156 |quote=Aksai Chin - the name, means the desert of white stones.}}</ref><ref name="Bhasin2006">{{cite book |author=Sanjeev Kumar Bhasin |title=Amazing Land Ladakh: Places, People, and Culture |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8IZloNzI8BgC&pg=PA61 |year=2006 |publisher=Indus Publishing |isbn=978-81-7387-186-3 |page=61 |quote=The Aksai Chin (desert of white stones)}}</ref> Some modern sources interpret it to mean "white brook" instead.<ref name="Butalia2015">{{cite book |author=Bob Butalia |title=In the Shadow of Destiny |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8CKrCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT271 |date=30 September 2015 |publisher=Partridge Publishing India |isbn=978-1-4828-5791-7 |page=271 |quote='Aksai Chin' in translation means 'White Brook Pass'.}}</ref><ref name="Kochhar2018">{{cite book |author=Geeta Kochhar |title=China's Foreign Relations and Security Dimensions |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9xZSDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT40 |date=19 March 2018 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-429-01748-3 |pages=40– |quote=The etymology of Aksai Chin is uncertain. Although 'Aksai' is a Turk term for 'white brooks', it is widely believed that the word 'chin' has nothing to do with China.}}</ref> At least one source interprets ''Aksai'' to mean "eastern" in the ].<ref name="Kapadia2002">{{cite book |author=Harish Kapadia |title=High Himalaya Unknown Valleys |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KNhJXSjSk70C&pg=PA309 |date=March 2002 |publisher=Indus Publishing |isbn=978-81-7387-117-7 |page=309 |quote=Aksai Chin, (Aksai: eastern, Chin: China) ... Most of the names were found to be distinctly Yarkandi.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| Aksai Chin is one of the two main disputed border areas between India and China. India claims Aksai Chin as the eastern-most part of the Jammu and Kashmir state. The line that separates Indian-administered areas of ] from Aksai Chin is known as the Cease Fire Line or ] (LAC) and is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line. | |||

| The word "Chin" was taken to mean ] by some Chinese,<ref name="cihai"/><ref name="gongbao"/><ref name="rfa">{{cite web |url=https://www.rfa.org/uyghur/obzor/obzor-sidik-06222010191805.html |title=ئاقساي چىنمۇ ياكى ئاقساي چۆلمۇ؟ |date=22 June 2010 |access-date=18 January 2020 |publisher=] |language=ug |quote=ماقالە يازغۇچى داۋاملاشتۇرۇپ: بۇ تېررىتورىيىنىڭ نامى تۈرك تىلىدا، "ئاقساي چىن " دېيىلىدۇ، بۇ ئىسىمدىكى "چىن" سۆزى جۇڭگونى كۆرسىتىدۇ، ئېيتىشلارغا ئاساسلانغاندا، بۇ سۆزنىڭ مەنىسى – " جۇڭگونىڭ ئاق تاشلىق جىلغىسى ياكى جۇڭگونىڭ ئاق تاشلىق سېيى" دېگەنلىك بولىدۇ دەيدۇ. |trans-title=Is Aksai True or Aksai Desert? |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100905212401/http://www.rfa.org/uyghur/obzor/obzor-sidik-06222010191805.html |archive-date=5 September 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref> Western,<ref name="british_india_1862" /><ref name="HedinAmbolt1967"/> and Indian sources.<ref name="Kapadia2002"/> At least one source takes it to mean "pass".<ref name="Butalia2015"/> Other sources omit "Chin" in their interpretations.<ref name="asiatic_society"/><ref name="Kaminsky"/><ref name="naval_war_college"/><ref name="Lintner2018"/><ref name="Kler1995"/><ref name="Bhasin2006"/> Van Driem states that there is no Uyghur word resembling "chin" for China.<ref name="van Driem"/> | |||

| Topographically, Aksai Chin is a high altitude desert. In the southwest, the ] range form the Line of Actual Control between Aksai Chin and rest of Ladakh to the east. Glaciated peaks in the mid portion of this line of actual control reach heights of {{convert|6950|m|ft}}. | |||

| Amin's Aksai Chin was not a defined region, stretching indefinitely east into Tibet south of the ].<ref>{{harvp|Mehra, An "agreed" frontier|1992|p=79}}: | |||

| In the north, the ] separates Aksai Chin from the ], where ] is situated. According to a recent detailed Chinese map, no roads cross the Kunlun Range within Hotan Prefecture, and only one track does so, over the ] Pass.<ref name=xuar>Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Road Atlas (中国分省公路丛书:新疆维吾尔自治区), published by 星球地图出版社 ''Xingqiu Ditu Chubanshe'', 2008, ISBN 978-7-80212-469-1. Map of Hotan Prefecture, pp. 18-19.</ref> | |||

| "The name 'Aksai Chin' occurred on a map captioned 'Rough sketch of caravan routes through the Pamir steppes and Yarkand, from information collected' from Mahomed Ameen Yarkandi , 'late guide' to the well-known Schlagintweit brothers. This was compiled in the Quartermaster-General's office in 1862. The sketch, which offered no details this side of the Kunlun, had 'Aksai Chin' written right across the blank space south of the Kunlun range. Mahomed Ameen had noted that 'beyond the pass (north of the Chang Chenmo) lies the Aksai Chin. ... it extends to Chinese territory to the East.'" | |||

| The ] of Kashmír and Ladák compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch and first Published in 1890 gives a description and details of places inside Kashmir and thus ipso facto also includes a description of the Híñdutásh Pass in north eastern Kashmir in the Aksai Chin area in Kashmir . The aforesaid Gazetteer states in pages 520 and 364 that “The eastern (Kuenlun) range forms the southern boundary of Khotan”, “and is crossed by two passes, the Yangi or Elchi Diwan, .... and the Hindutak (i.e. Híñdutásh ) Díwán”. The aforesaid Gazetteer of Kashmír and Ladák describes ] as “ A province of the Chinese Empire lying to the north of the Eastern Kuenlun range, which here forms the boundary of Ladák<ref>The ] of Kashmír and Ladák compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch and first Published in 1890, at page 493</ref>”. | |||

| </ref><ref> | |||

| {{citation |last=Brescius |first=Moritz von |title=German Science in the Age of Empire |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4lqHDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA197 |year=2019 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-42732-6 |pages=197–199 (including Map 5.2: 'Rough Sketch of Caravan Routes through the Pamir Steppes and Yarkund, from Information Collected from Mahomed Ameen Yarkundi, Late Guide to Messrs. De Schlagintweit')}} | |||

| </ref> In 1895, the British envoy to ] told the Chinese Taotai that Aksai Chin was a "loose name for an ill-defined, elevated tableland", part of which lay in Indian and part in Chinese territory.{{sfnp|Mehra, An "agreed" frontier|1992|p=11}} | |||

| The current meaning of the term is the area under dispute between India and China, having evolved in repeated usage since Indian independence in 1947. | |||

| The northern part of Aksai Chin is referred to as the Soda Plain and contains Aksai Chin's largest river, the ], the Gomati river of ] Kashmir, which receives meltwater from a number of glaciers, crosses the Kunlun farther northwest, in ] and enters the Tarim Basin, where it serves as one of the main sources of water for ] and Hotan Counties. | |||

| The eastern part of the region contains several small ] basins. The largest of them is that of the ], which is fed by the river of the same name. | |||

| The region is almost uninhabited, has no permanent settlements, and receives little precipitation as the ] and the Karakoram block the rains from the Indian ]. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{See also|Origins of the Sino-Indian border dispute}} | {{See also|Origins of the Sino-Indian border dispute}} | ||

| ] map of India. The undefined boundary shown in dashed line runs through ], ], ] and the ].]] | |||

| Because of its {{convert|5000|m|adj=on}} elevation, the desolation of Aksai Chin meant that it had no human importance.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell">{{cite book |title=India's China War |last=Maxwell |first=Neville |author-link=Neville Maxwell |year=1970 |publisher=Pantheon |location=New York |url=https://www.scribd.com/doc/12249475/Indias-China-War-Neville-Maxwell |page=3 |quote=At 17,000 feet elevation, the desolation of Aksai Chin had no human importance other than an ancient trade route that crossed over it, providing a brief pass during summer for caravans of yaks from Sinkiang to Tibet that carried silk, jade, hemp, salt |access-date=4 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131101121143/http://www.scribd.com/doc/12249475/Indias-China-War-Neville-Maxwell |archive-date=1 November 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> For military campaigns, the region held great importance, as it was on the only route from the ] to Tibet that was passable all year round.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Gaver|first1=John W.|title=Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century|date=2011|publisher=University of Washington Press|isbn=978-0295801209|page=83|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TOVaMckcO0MC&pg=PA83| access-date = 4 January 2020|quote= The westerly route via Aksai Chin was an old caravan route and in many ways the best. It was the only route that was open year-round, throughout both the winter and the monsoon season. The Dzungar army that had reached Lhasa in 1717 ... had followed this route.}}</ref> | |||

| ] was conquered in 1842 by the armies of Raja ] (Dogra) under the suzerainty of the ].{{sfn|Maxwell, India's China War|1970|p=24}}<ref name="Rubin">The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan. 1960), pp. 96–125, {{JSTOR|756256}}.</ref> The ] resulted in the transfer of the ] region including Ladakh to the British, who then installed Gulab Singh as the Maharaja under their suzerainty. The British appointed a boundary commission headed by Alexander Cunningham to determine the boundaries of the state. Chinese and Tibetan officials were invited to jointly demarcate the border, but they did not show any interest.{{sfn|Maxwell, India's China War|1970|p=25–26}} The British boundary commissioners fixed the southern part of the boundary up to the ], but regarded the area north of it as ''terra incognita''.{{sfn|Maxwell, India's China War|1970|p=26}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Aksai Chin was historically part of the ] Kingdom of ] until Ladakh was annexed from the rule of the local ] by the ]s and the ] of ] in the 19th century. It was subsequently absorbed into British India. One of the main causes of the ] of 1962 was India's discovery of a road China had built through the region, which is historically part of Ladakh. According to Rolf Alfred Stein author of Tibetan Civilization, the area of ] was not historically a part of Tibet and was a distinctly foreign territory to the Tibetans. According to Rolf Alfred Stein<ref> Tibetan Civilization by R.A. Stein Faber and Faber </ref>, | |||

| {{quote|" “…Then further west, The Tibetans encountered a distinctly foreign nation. - Shangshung, with its capital at Khyunglung. Mt. Kailāśa (Tise ) and Lake Manasarovar formed part of this country., whose language has come down to us through early documents. Though still unidentified, it seems to be Indo European. …Geographically the country was certainly open to India, both through Nepal and by way of Kashmir and Ladakh. Kailāśa is a holy place for the Indians, who make pilgrimages to it. No one knows how long they have done so, but the cult may well go back to the times when Shangshung was still independent of Tibet. | |||

| How far Shangshung stretched to the north , east and west is a mystery…. We have already had an occasion to remark that Shangshung, embracing Kailāśa sacred Mount of the Hindus, may once have had a religion largely borrowed from Hinduism. The situation may even have lasted for quite a long time. In fact, about 950, the ] King of ] had a statue of Vişņu, of the Kashmiri type (with three heads), which he claimed had been given him by the king of the Bhota (Tibetans) who, in turn had obtained it from Kailāśa.” }} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| A ] of Ladakh compiled in the 17th century called the La dvags rgyal rabs, meaning the Royal Chronicle of the Kings of Ladakh recorded that this boundary was traditional and well-known. The first part of the Chronicle was written in the years 1610 -1640, and the second half towards the end of the 17th century. The work has been translated into English by A. H. Francke and published in 1926 in Calcutta titled the “Antiquities of Indian Tibet” . In volume 2, the Ladakhi Chronicle describes the partition by King Sykid-Ida-ngeema-gon of his kingdom between his three sons, and then the chronicle described the extent of territory secured by that son. The following quotation is from page 94 of this book: | |||

| {{quote|" "He gave to each of his sons a separate kingdom, viz., to the eldest Dpal-gyi-ngon, Maryul of Mnah-ris, the inhabitants using black bows; ru-thogs of the east and the Gold-mine of Hgog; nearer this way Lde-mchog-dkar-po; at the frontier ra-ba-dmar-po; Wam-le, to the top of the pass of the Yi-mig rock…..”}} | |||

| === The Johnson Line === | |||

| From a perusal of the aforesaid work, It is obvious and evident that Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh and even after the family partition, Rudokh continued to be part of Ladakh. Maryul meaning lowlands was a name given to a part of Ladakh. Even at that time, i.e. in the 10th century, Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh and Lde-mchog-dkar-po, i.e. Demchok was also an integral part of Ladakh. | |||

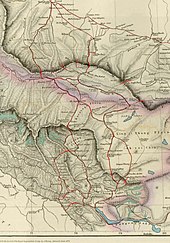

| ] (1873) from ]. ] is near top right corner. The border claimed by the ] is shown in the two-toned purple and pink band with ] and the Kilik, Kilian and ] Passes north of the border.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Johnson Line (boundary)}} | |||

| ], a civil servant with the ] proposed the "Johnson Line" in 1865, which put Aksai Chin in Kashmir. This was the time of the ], when China did not control most of ], so this line was never presented to the Chinese. Johnson presented this line to the Maharaja of Kashmir, who then claimed the 18,000 square kilometres contained within,<ref name="Guruswamy">Mohan Guruswamy, Mohan, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160930222001/http://www.rediff.com/news/2003/jun/20spec.htm |date=30 September 2016 }}, ], 23 June 2003.</ref>{{unreliable source?|date=October 2019|reason=See ]}} and by some accounts territory further north as far as the ] in the ]. The Maharajah of Kashmir constructed a fort at Shahidulla (modern-day ]), and had troops stationed there for some years to protect caravans.{{sfn|Woodman|1969|pp=101, 360ff}} Eventually, most sources placed Shahidulla and the upper ] firmly within the territory of Xinjiang (see accompanying map).{{citation needed|date=October 2019}} According to ], who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there – it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic ].<ref>Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). ''The Heart of a Continent''. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics, pp. 223–224.</ref>{{primary-source-inline|date=October 2019}} The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Kashmiris.<ref>Grenard, Fernand (1904). ''Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants''. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974, pp. 28–30.</ref>{{primary-source-inline|date=October 2019}} In 1878 the Chinese had ], and by 1890 they already had Shahidulla before the issue was decided.<ref name="Guruswamy"/>{{unreliable source?|date=October 2019|reason=See ]}} By 1892, China had erected boundary markers at ].<ref name="Calvin">{{cite web|last=Calvin|first=James Barnard|date=April 1984|url=https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/CJB.htm|title=The China-India Border War|publisher=Marine Corps Command and Staff College|access-date=|archive-url=|archive-date=|url-status=}}</ref> | |||

| In 1897, a British military officer, ], proposed a boundary line along the crest of the ] north of the ].{{sfn|Woodman|1969|pp=101, 360ff}} At that time, Britain was concerned about the danger of Russian expansion as China weakened, and Ardagh argued that his line was more defensible. The Ardagh line was effectively a modification of the Johnson line, and became known as the "Johnson-Ardagh Line". | |||

| At an elevation of 5,000m, the desolation of Aksai Chin had no human importance other than an ancient trade route that crossed over it, providing a brief pass during summer for caravans of yaks between Xinjiang and Tibet.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell">Maxwell, Neville, , New York, Pantheon, 1970.</ref> | |||

| The Aksai Chin area was traversed in 1865 by W. H. Johnson , Civil Assistant of the Trigonometrical Survey of India of the ]. In July 1865, he was instructed to explore the country of Khotan. “He followed the familiar route from Leh as far as Kyam, and then broke news ground by marching in a northern direction. He travelled through NIschu, Huzakhar, and Yangpa, describuing these isolated places in the Aksai Chin in great detail. He was the first European to cross the Yangi Diwan Pass between Tash and Khushlashlangar, and to take a route which Juma Khan, ambassador from Khotan to the British Government, had travelled some time before. He waited at the source of the Kara Kash for someone to receive him at the first village on the northern side of the Kuen Lun. On the twelfth day his patience was rewarded; a bearer came from the Badsha of Khotan saying ‘he had dispatched his wazeer, Sarfulla Khoja, to meet me at Bringja, the first encampment beyond the Ladakh boundary, for the purpose of escorting me to Khotan. Three miles from Khotan, Khan’s two sons were waiting to welcome him. The Khan had a great deal to say. Four years before he had visited Mecca and on his return he was made the chief Kasi of Khotan. ‘Within a month,’ he said ‘he succeeded in raising a rebellion against the Chinese, which resulted in their massacre, and his election by the inhabitants of the country to be their Khan Badsha or ruler.’ When the Chinese were defeated in Khotan, Yarkand, Kashgar, and other places in Central Asia, Yaqub Beg set up an independent Muslim country which survived until 1877 when the Chinese troops recaptured Kashgar”. W.H. Johnson’s survey established certain important points. "Brinjga was in his view the boundary post" ( near the Karanghu Tagh Peak in the Kuen Lun in Ladakh ), thus implying "that the boundary lay along the Kuen Lun Range"<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.</ref>. Johnson’s findings demonstrated that the whole of the Kara Kash valley was “ within the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir” and an integral part of the territory of Kashmir . "He noted where the Chinese boundary post was accepted. At Yangi Langar, three marches from ] , he noticed that there were a few fruit trees at this place which originally was a post or guard house of the Chinese". “The Khan wrote Johnson ‘that he had dispatched his Wazier, Saifulla Khoja to meet me at Bringja, the first encampment beyond the Ladakh boundary for the purpose of escorting me thence to Ilichi’… thus the Khotan ruler accepted the Kunlun range as the southern boundary of his dominion.”<ref>Himalayan Battleground by Margaret W. Fisher, Leo E. Rose and Robert A. Huttenback, published by Frederick A. Praeger Pg.116. </ref> According to Johnson, “the last portion of the route to Shadulla (Shahidulla) is particularly pleasant, being the whole of the Karakash valley which is wide and even, and shut in either side by rugged mountains. On this route I noticed numerous extensive plateaux near the river, covered with wood and long grass. These being within the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir, could easily be brought under cultivation by Ladakhees and others, if they could be induced and encouraged to do so by the Kashmeer Government. The establishment of villages and habitations on this river would be important in many points of view, but chiefly in keeping the route open from the attacks of the Khergiz robbers.” <ref>Report of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, 1866, p.6. </ref> | |||

| In the words of Dorothy Woodman, “But for its accessibility, Aksai Chin might have been used as an alternate rioute for traders who could have thereby escaped the high duties imposed by the Maharaja of Kashmir. '''The Kashmir authorities maintained two caravan routes right upto the traditional boundary. One, from Pamzal, known as the Eastern Changchenmo route, passed through Nischu, ], Lak Tsung, Thaldat, Khitai Pass, Haji Langar along the Karakash valley”(obviously via ]) “to ]. Police outposts were placed along these routes to protect the traders from the Khirghiz marauders who roamed the Aksai Chin after ]’s rebellion against the Chinese(1864-1878)'''”<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.66, published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969</ref>. | |||

| The Chinese completed the reconquest of eastern Turkistan in 1878. Before they lost it in 1863, their practical authority, as Ney Elias British Joint Commissioner in Leh from the end of the 1870s to 1885, and Younghusband consistently maintained, '''"had never extended south of their outposts at Sanju and Kilian along the northern foothills of the Kuenlun range. Nor did they establish a known presence to the south of the line of outposts in the twelve years immediately following their return"'''. <ref>Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at pages 56-57, 59, 95, Allied Publishers Private Ltd, New Delhi. </ref>Ney Elias who had been Joint Commissioner in Ladakh for several years noted on 21 September 1889 that he had met the Chinese in 1879 and 1880 when he visited Kashgar. ''“they told me that they considered their line of ‘chatze’, or posts, as their frontier – viz. , Kugiar, Kilian, Sanju, Kiria, etc.- '''and that they had no concern with what lay beyond the mountains'''”''<ref>19. For. Sec.. F. October 1889, 182/197.</ref> i.e. the Kuen Lun range in northern Kashmir where the ] pass in Kashmir is situate. ] which literally means "Indian stone" in the Uyghur dialect of ] is a pass in the Kuen Lun range “which is the southern border of Khotan”<ref>Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch. First Published in 1890 by the Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta. Compiled under the Direction of the Quartermaster -General in India in the Intelligence Branch. 1890 Ed. Pg. 520, 364 | |||

| </ref>. | |||

| According to Ramsay, One Musa , nephew of the head–man (Turdi Kul) of the Kirghiz who marauded the area around the Shahidulla Fort and the Raskam sought help from the Chinese Amban at Yarkand. The Amban replied that “the Chinese frontier extended only to the Kilian and Sanju passes… he could do nothing for us so long as we remained at Shahidulla and he could not take notice of raids committed on us beyond the Chinese frontier”. Clearly, in 1889, the Kuen Lun was regarded as marking the southern frontier of East Turkistan<ref>India-China Boundary Problem, 1846-1947 History and Diplomacy by A.G. Noorani , Oxford University Press</ref>. As Alder wrote<ref>Alder, British India’s Northern Frontier, P.278</ref>, “the Chinese after return to Sinkiang in 1878, claimed up to the Kilian, Kogyar, and Sanju passes north of the Kuen Luen” . The Amban directed the Kirghiz to the authorities in Ladakh since no Chinese official ever comes to Ladakh. Musa was sent to Ladakh to ask for assistance, where he said, “The fort at Shahidulla belongs to the Kashmir state, but as it is at present in ruins, we desire to be given the money to rebuild it<ref>Statement of Musa Kirghiz of Shahidullah recorded by Ramsey on 25 May 1889, Foreign Secret F., July 1889, No. 205</ref>” Though, Ramsay later stated that Musa was not reliable and was altering his statements, it was confirmed that the Amban did say that the frontier was at the southern base of the Kilian pass in the Kuen Lun range, and that the Turdi Kol was “certainly told by the Chinese Amban that Shahidulla was not in Chinese territory<ref>Foreign Secret F., July 1889, No. 203-30</ref>” Younghusband arrived in Shahidulah on 21 August 1889 and met the Turdi Kol, the Kirghiz chief himself rather than Musa. Two Chinese officials , the Kargilik and the Yarkand Amban had told him that Shahidulla was British territory i.e. part of the territory of Kashmir. He also examined the Shahidullah Fort. | |||

| === The Macartney–Macdonald Line === | |||

| {{main|Macartney–MacDonald Line}} | |||

| T.D. ] who was entrusted with the rather unambiguous task of visiting the Court of Atalik Ghazi pursuant to the visit on 28, March 1870 of the envoy of Atalik Ghazi, Mirza Mohammad Shadi , stated that "...it would be very unsafe to define the boundary of Kashmir in the direction of the Karakoram…. Between the Karakoram and the Karakash the high Plateau is perhaps rightly described as rather a no-mans land , but I should say with a tendency to become Kashmir property". Two stages beyond Shahidulla, as the route headed for Sanju, Forsyth’s party crossed the Tughra Su and passed an out post called Nazr Qurghan.“This is manned by soldiers from Yarkand”.<ref>For. Pol.A. January 1871, 382/386, para58 </ref> In the words of John Lall, “Here we have an early example of coexistence. The Kashmiri and Yarkandi outposts were only two stages apart on either side of the Karakash river...<ref>Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at pages57-58, 61,69 Allied Publishers Private Ltd, Nav Dehli</ref>" '''to the northwest of the''' Hindutash in the north eastern frontier region of Kashmir. This was the ] that prevailed at the time of the mission to Kashgar in 1873-74 of Sir Douglas Forsyth. “Elias himself recalled that , following his mission to Kashgar in 1873-74, Sir Douglas Forsyth ‘recommended the Maharaja’s boundary to be drawn to the north of the Karakash valley ''as shown in the map accompanying the mission report’''. Elias’ reasons for suggesting a boundary '''''that went against the situation on the ground and the recommendations of Sir Douglas Forsyth''''', who had been directed by the Government of India to ascertain the boundaries of the Ruler of Yarkand, seem to have been prompted atleast partly , by his ill- concealed contempt for the Ladakh Wazir’s plans”.This had been motivated by the discovery of a ] mine near the Kashmiri outpost at Shahidulla by a Pathan from Bajaur, not a Kashmiri, as if the nationality of the finder had anything to do with the rights to the territory. Lapis lazuli, he pointed out , had no value at the time. “So the only reason for raising the question is a worthless one, and prompted only by '''the usual Kashmiri greed for every thing they can lay hands upon'''.”<ref>For. Sec. F.Pros. November 1885, 12/14(12)</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| When the Government of Kashmir in 1885, at a time when the Chinese were least concerned or bothered of the alien trans- Kuen Lun areas in the ] of Kashmir , beyond their eastern Turkistan dominion and literally “had washed their hands of it<ref>Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at page 60, Allied Publishers Private Ltd, New Delhi</ref>”, prepared to reunify Kashmir and the Wazir of Ladakh , Pandit Radha Kishen initiated steps to restore the old Kashmiri outpost at Shahidulla, Ney Elias who was British Joint Commissioner in Ladakh and spying on the Government of Kashmir raised objections. “This very energetic officer’ , he wrote to the resident, who duly forwarded the letter to the Government of India, “wants the Maharaja to reoccupy Shahidulla in the Karakash valley ….I see indications of his preparing to carry it out, and, in my opinion, he should be restrained, or an awkward boundary question may be raised with the Chinese '''without any compensating advantage'''<ref>Sec. F. November 1885,12/14(12) </ref>”. In the circumstances, since Elias had represented to the Supreme Government, it was a relatively simple matter for him to ensure that the plans were dropped. He told the Wazir that he had reported against the scheme to the Resident, and pretty soon the subservient Wazir succumbed and assured him that he did not intend to implement it. Elias was also promptly meticulously backed up by the Government of India. A letter dated 1st September was sent to the officer on Special Duty (as the Resident was called before 1885) instructing him to take suitable opportunity of advising His Highness the Maharaja not to occupy Shahidulla”. Elias had already killed the proposal. Kashmir, however never forfeited her territorial integrity, though she had been under ] and ] prevented from restoring the outpost at Shahidulla to command the Kuen Lun. | |||

| In 1893, Hung Ta-chen, a senior Chinese official at ], gave maps of the region to ], the British consul general at Kashgar, which coincided in broad details.{{sfn|Woodman|1969|pp=73, 78}} In 1899, Britain proposed a revised boundary, initially suggested by Macartney and developed by the Governor General of India ]. This boundary placed the Lingzi Tang plains, which are south of the Laktsang range, in India, and Aksai Chin proper, which is north of the Laktsang range, in China. This border, along the ]s, was proposed and supported by British officials for a number of reasons. The Karakoram Mountains formed a natural boundary, which would set the British borders up to the ] ] while leaving the ] watershed in Chinese control, and Chinese control of this tract would present a further obstacle to Russian advance in Central Asia.<ref name="Noorani">{{Citation | last=Noorani | first=A.G. | date=30 August – 12 September 2003 | title=Fact of History | magazine=Frontline | volume=26 | issue=18 | publisher=The Hindu group | location=Madras | access-date=24 August 2011 | url=http://frontlineonnet.com/fl2018/stories/20030912002104800.htm | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111002095213/http://frontlineonnet.com/fl2018/stories/20030912002104800.htm | archive-date=2 October 2011 | url-status=dead}}</ref> The British presented this line, known as the ], to the Chinese in 1899 in a note by Sir ]. The Qing government did not respond to the note.{{sfn|Woodman|1969|p=102|ps=: The proposed boundary seems never to have been considered in the same form again until Alastair Lamb revived it in 1964}} According to some commentators, China believed that this had been the accepted boundary.<ref name=middlepath>{{cite journal|last1=Verma|first1=Virendra Sahai|year=2006|title=Sino-Indian Border Dispute at Aksai Chin – A Middle Path For Resolution|journal=Journal of Development Alternatives and Area Studies|volume=25|issue=3|pages=6–8|issn=1651-9728}}</ref> | |||

| === McMahon line === | |||

| The Chinese Karawal or outpost, of Sanju was at the northern base of the Kuenlun, three stages from the pass of that name. Nevertheless, F.E.Younghusband could not disguise the objective fact that the Chinese considered the Kilian and ]es as the practical limits of their territory, although they ‘do not like to go so far as to say that beyond the passes does not belong to them….”<ref>For.Sec.F.Pros.October 1889,182/197(184)</ref>. | |||

| {{Main|McMahon line}} | |||

| In 1893, Hung Ta Chen , a senior Chinese official had given officially a map to the British Indian Counsel at Kashgar. It clearly shows the major part of Aksai Chin and Lingzi Thang in India. Besides, in 1917, The Government of China had also published the “Postal map of China”, published at Peking in 1917. "It shows the whole northern Boundary of India more or less according to the traditional Indian alignments"<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68,81, published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.</ref>. Actually, an imperialist map of China during the relevant period, besides the depiction of Aksai Chin as part of India, the map incidentally depicts all the pre-1947 Himalayan princely states in Pre-1947 India including inter alia Nepal, Sikkim, and what is now Arunachal Pradesh as integral parts of India. | |||

| The line is named after ], foreign secretary of ] and the chief British negotiator of the conference at Simla. The bilateral agreement between Tibet and Britain was signed by McMahon on behalf of the British government and ] on behalf of the Tibetan government.<ref name="Rao2003">{{cite book |last=Rao |first=Veeranki Maheswara |title=Tribal Women of Arunachal Pradesh: Socio-economic Status |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X4OrJH9yJfwC&pg=PA60 |access-date=25 May 2017 |year=2003 |publisher=Mittal Publications |isbn=978-81-7099-909-6 |pages=60– |archive-date=28 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230728221747/https://books.google.com/books?id=X4OrJH9yJfwC&pg=PA60 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The renowned German geologist visited Aksai Chin in 1927. He called it the4 westernmost Plateaux of Tibet’ because, he writes, ‘geographically the Lingzithang and Aksai-chin are Tibetan, though politically they are situated in Ladakh. “His journal reveals that there were no Chinese in this part of the country, and that it was indeed within the boundaries of India”. "I must confess", he wrote "that I have rarely seen such utterly barran and desolate mountains".<ref>* Trinkler , Dr. Emil, Himalayan Jounnal, Volumes 3 and 4, 1931-32, April 1931. Notes on the Westernmost Plateau of Tibet. | |||

| </ref> | |||

| One of the earliest treaties regarding the boundaries in the western sector was issued in 1842. The ] of the ] in India had annexed ] into the state of ] in 1834. In 1841, they invaded Tibet with an army. Chinese forces defeated the Sikh army and in turn entered Ladakh and besieged ]. After being checked by the Sikh forces, the Chinese and the Sikhs signed a treaty in September 1842, which stipulated no transgressions or interference in the other country's frontiers.<ref name="Rubin">The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-125.</ref> The ] resulted in transfer of sovereignty over Ladakh to the British, and British commissioners attempted to meet with Chinese officials to discuss the border they now shared. However, both sides were apparently sufficiently satisfied that a traditional border was recognized and defined by natural delements, and the border was not demarcated.<ref name="Rubin"/> The disputed boundaries at the two extremities, ] and ], were well-defined, but the Aksai Chin area in between lay undefined.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/><ref name="Guruswamy2006">{{cite book |title= Emerging Trends in India-China Relations |last= Guruswamy |first= Mohan |year= 2006 |month=January |publisher= Hope India Publications |location= India |isbn= 9788178711010 |page= 222 |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=trAb0KxP_ocC&pg=PA222 |accessdate=2009-09-12}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== 1899 to 1947 === | ||

| Both the Johnson-Ardagh and the Macartney-MacDonald lines were used on British maps of India.<ref name="Guruswamy"/>{{unreliable source?|date=October 2019|reason=See ]}} Until at least 1908, the British took the Macdonald line to be the boundary,{{sfn|Woodman|1969|p=79}} but in 1911, the ] resulted in the collapse of central power in China, and by the end of ], the British officially used the Johnson Line. However they took no steps to establish outposts or assert actual control on the ground.<ref name="Calvin"/> In 1927, the line was adjusted again as the government of British India abandoned the Johnson line in favor of a line along the Karakoram range further south.<ref name="Calvin"/> However, the maps were not updated and still showed the Johnson Line.<ref name="Calvin"/> | |||

| ] (1878) showing ] (near top right corner). The previous border claimed by the ] is shown in the two-toned purple and pink band with ] and the Kilik, Kilian and Sanju Passes clearly north of the border.]] | |||

| ] in 1917. The boundary in Aksai Chin is as per the Johnson line.|alt=]] | |||

| W. H. Johnson, a civil servant with the ] proposed the "Johnson Line" in 1865, which put Aksai Chin in Kashmir.<ref name="Guruswamy">Mohan Guruswamy, Mohan, , Rediff, June 23, 2003.</ref> This was the time of the ], when China did not control ](which the Chinese subsequently renamed ] or new dominion), so this line was never presented to the Chinese.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> Johnson presented this line to the Maharaja of Kashmir, who then claimed the 18,000 square kilometres contained within,<ref name="Guruswamy"/> and by some accounts territory further north as far as the ] in the ]. Johnson's work was severely criticized for gross ] inaccuracies, with description of his boundary as "patently absurd".<ref name="Calvin">{{cite web | |||

| From 1917 to 1933, the ''Postal Atlas of China'', published by the Government of China in Peking had shown the boundary in Aksai Chin as per the Johnson line, which runs along the ].{{sfn|Woodman|1969|pp=73, 78}}<ref name=middlepath /> The ''Peking University Atlas'', published in 1925, also put the Aksai Chin in India.<ref name="HimalayanBground">{{cite book|last1=Fisher|first1=Margaret W.|last2=Rose|first2=Leo E.|last3=Huttenback|first3=Robert A.|title=Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh|date=1963|publisher=Praeger|page=101|url=https://www.questia.com/read/10466588|url-access=|via=|isbn=|access-date=24 August 2017|archive-date=30 September 2014|archive-url=https://archive.today/20140930113800/http://www.questia.com/read/10466588|url-status=dead}}{{ISBN?}}</ref> When British officials learned of Soviet officials surveying the Aksai Chin for ], warlord of ] in 1940–1941, they again advocated the Johnson Line. At this point the British had still made no attempts to establish outposts or control over the Aksai Chin, nor was the issue ever discussed with the governments of China or Tibet, and the boundary remained undemarcated at India's independence.<ref name="Calvin"/><ref name="Orton p. 24">{{cite book | last=Orton | first=Anna | title=India's Borderland Disputes: China, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal | publisher=Epitome Books | isbn=978-93-80297-25-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vcwkEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA24 | page=24}}</ref> | |||

| | last =Calvin | |||

| | first =James Barnard | |||

| | date = April 1984 | |||

| | url = http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/CJB.htm | |||

| | title =The China-India Border War | |||

| | publisher = Marine Corps Command and Staff College | |||

| | accessdate =2011-10-14 | |||

| }}</ref> Johnson was reprimanded by the British Government and resigned from the Survey.<ref name="Calvin" /><ref name="Guruswamy"/><ref name="Noorani">{{Citation | last=Noorani | first=A.G. |publication-date=30 August-12 September 2003 |title=Fact of History | magazine=Frontline | volume=26 | issue=18 |publisher=The Hindu group | publication-place=Madras | accessdate=24 August 2011 | url=http://frontlineonnet.com/fl2018/stories/20030912002104800.htm }}</ref> The Maharajah of Kashmir apparently had constructed a fort and engaged soldiers to man the fort at Shahidulla for over 20 years at one point, but most ] placed Shahidulla and the upper ] firmly within the territory of Xinjiang (see accompanying map). According to ], who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there - it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic ].<ref>Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). ''The Heart of a Continent''. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics, pp. 223-224.</ref> The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Kashmiris.<ref>Grenard, Fernand (1904). ''Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants''. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974, pp. 28-30.</ref> In 1878 the Chinese had reconquered Xinjiang, and by 1890 they already had Shahidulla before the issue was decided.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> By 1892, China had erected boundary markers at ].<ref name="Calvin"/> . This act was objected by the Kashmiri Government official as the Government of Kashmir regarded ] as part of Kashmir, but the ] Government of India choose to ignore the objections. Colonel Walker who was the Surveyor General in 1867 “insisted that the map as published was far different from Johnson’s Original”. | |||

| === Since 1947 === | |||

| In 1897 a British military officer, Sir John Ardagh, proposed a boundary line along the crest of the ] north of the ].<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| ], 1950)]] | |||

| | last = Woodman | |||

| After ] ] to the newly independent India in October 1947, the government of India used the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the west, which included the Aksai Chin.<ref name="Calvin"/> From the Karakoram Pass (which is not under dispute), the Indian claim line extends northeast of the Karakoram Mountains through the salt flats of the Aksai Chin, to set a boundary at the ], and incorporating part of the ] and ] watersheds. From there, it runs east along the Kunlun Mountains, before turning southwest through the Aksai Chin salt flats, through the Karakoram Mountains, and then to ].<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> | |||

| | first = Dorothy | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Himalayan Frontiers | |||

| | publisher = Barrie & Rockcliff | |||

| | year = 1969 | |||

| | location = | |||

| | pages = 101 and 360ff | |||

| | url = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | id = | |||

| | isbn = }}</ref> At the time Britain was concerned at the danger of Russian expansion as China weakened, and Ardagh argued that his line was more defensible. The Ardagh line was effectively a modification of the Johnson line, and became known as the "Johnson-Ardagh Line". | |||

| On 1 July 1954, Prime Minister ] wrote a memo directing that the maps of India be revised to show definite boundaries on all frontiers. Up to this point, the boundary in the Aksai Chin sector, based on the Johnson Line, had been described as "undemarcated."<ref name="Noorani"/> | |||

| === The Macartney-Macdonald Line === | |||

| In the 1890s Britain and China were allies and Britain was principally concerned that Aksai Chin not fall into ]n hands.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> In 1899, when China showed an interest in Aksai Chin, Britain proposed a revised boundary, initially suggested by ],<ref name="Calvin"/> which put most of Aksai Chin in Chinese territory.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> This border, along the ]s, was proposed and supported by British officials for a number of reasons which would set the British borders up to the ] ] while leaving the ] watershed in Chinese control, and Chinese control of this tract would present a further obstacle to Russian advance in Central Asia.<ref name="Noorani"/> The British presented this line to the Chinese in a Note by Sir ]. The Chinese did not respond to the Note, and the British took that as Chinese acquiescence.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> This line, known as the Macartney-MacDonald line, is approximately the same as the current Line of Actual Control.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> | |||

| In the words of Dorothy Woodman author of “ Himalayan Frontiers”, “The simple fact was the inaccessible and practicably uninhabited area between the Karakoram and Kuenlun ranges was of interest to the (English colonial )Indian Government only in terms of the Russian threat.” "<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.55-56 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.</ref> And that the alleged so-called “no man’s land” under the control of the Chinese was useful, in the words of ], “to us as an obstacle to Russian advance along this line”. So when Chinese control over ] seemed to be on the verge of a very eminent and inevitable collapse, it suited the English ]s to talk of the so called “Ardagh Line” as though the so- called “Ardagh Line” was an artificial and invented concept, ignoring the fact that there was ] of evidence and no ] in the availability of evidence that the Kuen lun area had always been part of the ] in the ] of Kashmir notably ], ] and ]. | |||

| According to Dorothy Woodman author of "Himalayan Frontiers" writing on the issue of the customary boundary between ] and ], “the map" ( ) "indicates that ''even in 1865'' that area" (wherein Hindutash and Sanju are situate) "was part of India and that the ''customary boundary was well known''” "<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.70-71 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.</ref>. | |||

| Despite this region being nearly uninhabitable and having no resources, it remains strategically important for China as it connects Tibet and Xinjiang. During the 1950s, the ] built a 1,200 km (750 mi) road connecting Xinjiang and western ], of which 179 km (112 mi) ran south of the Johnson Line through the Aksai Chin region claimed by India.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/><ref name="Calvin"/> Aksai Chin was easily accessible to the Chinese, but was more difficult for the Indians on the other side of the Karakorams to reach.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> The Indians did not learn of the existence of the road until 1957, which was confirmed when the road was shown in Chinese maps published in 1958.<ref name="Garver"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090326032121/http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~johnston/garver.pdf |date=26 March 2009 }}</ref> The construction of this highway was one of the triggers for the ] of 1962.<ref>{{cite book |last=Guo |first=Rongxing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z5Le627xQLgC&pg=PA43 |title=Territorial Disputes and Resource Management |date=2007 |publisher=Nova Science Publishers |isbn=978-1-60021-445-5 |page=43 |access-date=2019-06-10}}</ref> | |||

| === 1899 to 1947 === | |||

| Both the Johnson-Ardagh and the Macartney-MacDonald lines were used on British maps of India.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> Until at least 1908, the British took the Macdonald line to be the boundary,<ref>Woodman (1969), p.79</ref> but in 1911, the ] resulted in the collapse of central power in China, and by the end of ], the British officially used the Johnson Line. However they took no steps to establish outposts or assert actual control on the ground.<ref name="Calvin"/> In 1927, the line was adjusted again as the government of British India abandoned the Johnson line in favor of a line along the Karakoram range further south.<ref name="Calvin"/> However, the maps were not updated and still showed the Johnson Line.<ref name="Calvin"/> | |||

| The Indian position, as stated by Prime Minister Nehru, was that the Aksai Chin was "part of the Ladakh region of India for centuries" and that this northern border was a "firm and definite one which was not open to discussion with anybody".<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> | |||

| When British officials learned of Soviet officials surveying the Aksai Chin for ], warlord of ] in 1940-1941, they again advocated the Johnson Line.<ref name="Guruswamy"/> At this point the British had still made no attempts to establish outposts or control over the Aksai Chin, nor was the issue ever discussed with the governments of China or Tibet, and the boundary remained undemarcated at India's independence.<ref name="Guruswamy"/><ref name="Calvin"/> | |||

| In 1893, Hung Ta Chen , a senior Chinese official had given officially a map to the British Indian Counsel at Kashgar. It clearly shows the major part of Aksai Chin and Lingzi Thang in India. Besides, in 1917, The Government of China had also published the “Postal map of China”, published at Peking in 1917. "It shows the whole northern Boundary of India more or less according to the traditional Indian alignments"<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68,81, published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.</ref>. Actually, an imperialist map of China during the relevant period, besides the depiction of Aksai Chin as part of India, the map incidentally depicts all the pre-1947 Himalayan princely states in Pre-1947 India including inter alia Nepal, Sikkim, and what is now Arunachal Pradesh as integral parts of India. | |||

| The Chinese premier ] argued that the western border had never been delimited, that the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Aksai Chin within Chinese borders was the only line ever proposed to a Chinese government, and that the Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction, and that negotiations should take into account the status quo.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> | |||

| === Since 1947 === | |||

| Upon independence in 1947, the government of India used the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the west, which included the Aksai Chin<ref name="Calvin"/> From the Karakoram Pass (which is not under dispute), the Indian claim line extends northeast of the Karakoram Mountains through the salt flats of the Aksai Chin, to set a boundary at the ], and incorporating part of the ] and ] watersheds. From there, it runs east along the Kunlun Mountains, before turning southwest through the Aksai Chin salt flats, through the Karakoram Mountains, and then to ].<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> | |||

| In June 2006, ] on the ] service revealed a 1:500<ref name="age" /> scale terrain model of eastern Aksai Chin and adjacent ], built near the town of ], about {{convert|35|km}} southwest of ], the capital of the autonomous region of ] in China.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.indianexpress.com/news/from-sky-see-how-china-builds-model-of-indian-border-2400-km-away/9972/|title=From sky, see how China builds model of Indian border 2400 km away|date=5 August 2006|access-date=8 July 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110102182326/http://www.indianexpress.com/news/from-sky-see-how-china-builds-model-of-indian-border-2400-km-away/9972|archive-date=2 January 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> A visual side-by-side comparison shows a very detailed duplication of Aksai Chin in the camp.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081208110436/http://bbs.keyhole.com/ubb/showthreaded.php/Cat/0/Number/859782/page/0/vc/1 |date=8 December 2008 }}, 10 April 2007</ref> The {{convert|900|x|700|m|abbr=on}}{{Citation needed|reason=source "age" claims 3 km!|date=July 2009}} model was surrounded by a substantial facility, with rows of red-roofed buildings, scores of olive-coloured trucks and a large compound with elevated lookout posts and a large communications tower. Such terrain models are known to be used in military training and simulation, although usually on a much smaller scale. | |||

| On July 1, 1954 Prime Minister ] wrote a memo directing that the maps of India be revised to show definite boundaries on all frontiers. Up to this point, the boundary in the Aksai Chin sector, based on the Johnson Line, had been described as "undemarcated."<ref name="Noorani"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Local authorities in ] claim that their model of Aksai Chin is part of a tank training ground, built in 1998 or 1999.<ref name="age">{{cite news|url=http://www.theage.com.au/news/web/chinese-xfile-not-so-mysterious-after-all/2006/07/23/1153593217781.html|title=Chinese X-file not so mysterious after all|date=2006-07-23|newspaper=]|access-date=2008-12-17 | location=Melbourne| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20090113185611/http://www.theage.com.au/news/web/chinese-xfile-not-so-mysterious-after-all/2006/07/23/1153593217781.html| archive-date= 13 January 2009 | url-status= live}}</ref> | |||

| The territorial extent of the State of ] is as enumerated or stipulated in Entry 15 in the First Schedule of the ]. Entry 15 reads “The territory which immediately before the commencement of this Constitution was comprised in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir”. Section (4) of the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir states, “The territory of the State shall comprise all the territories which on the fifteenth day of August, 1947, were under the sovereignty or suzerainty of the Ruler of the State". The official maps attached to the 2 White Papers published in July 1948 and February 1950 by the Government of India's Ministry of States, headed, incidentally, by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, under the authority of India's Surveyor General G.F. Heaney bind it in law and give them the legal status to determine the extent of the territory of the State of Kashmir as stipulated in Entry 15 in the First Schedule of the Constitution on India. The said maps did not depict the northern and eastern border of Kashmir but only displayed the legend “Frontier undefined” or “boundary undefined”. The area depicted within the legend “boundary undefined” had a colour wash. But Mr. Jawaharlal Nehru for implementing the aforesaid Memo published a map which arbitrarily depicted even the areas which had hitherto been shown within the colour wash and within the legend “boundary undefined” or “Frontier undefined” thus depicted as integral part of ], as not part of ]. According to the Constitutional legal luminary luminary A.G. Noorani, “This raises a question of fundamental importance which has not been discussed all these decades. The Government of India’s shenanigans on the entire map business only invite ridicule”.<ref>Freedom of Expression in Maps, A.G. Noorani Chapter 44, pg. 327, appeared in “Frontline” Magazine, a Publication of The Hindu dated 8, May 1992. "Citizens' Rights, Judges and State Accountability"</ref>”. | |||

| In August 2017, Indian and Chinese forces near ] threw rocks at each other.<ref name="hket"/><ref>{{cite web|url=https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/india-china-conflict-in-ladakh-the-importance-of-the-pangong-tso-lake-6419377/|title=India-China conflict in Ladakh: The importance of the Pangong Tso lake|date=20 May 2020|access-date=21 May 2020|website=]|author=Sushant Singh}}</ref> | |||

| During the 1950s, the ] built a 1,200 km (750 mi) road connecting Xinjiang and western ], of which 179 km (112 mi) ran south of the Johnson Line through the Aksai Chin region claimed by India.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/><ref name="Guruswamy"/><ref name="Calvin"/> Aksai Chin was easily accessible to the Chinese, but was more difficult for the Indians on the other side of the Karakorams to reach.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> The Indians did not learn of the existence of the road until 1957, which was confirmed when the road was shown in Chinese maps published in 1958.<ref name="Garver"></ref> | |||

| On 11 September 2019, ] troops confronted Indian troops on the northern bank of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.news18.com/news/india/indian-chinese-troops-face-off-in-ladakh-month-ahead-of-modi-xi-jinping-summit-2305615.html|title=Indian, Chinese Troops Face-off in Ladakh Ahead of Modi-Xi Summit, Army Says Tension De-escalated|date=12 September 2019|access-date=12 May 2020|work=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191107231903/https://www.news18.com/news/india/indian-chinese-troops-face-off-in-ladakh-month-ahead-of-modi-xi-jinping-summit-2305615.html|archive-date=7 November 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.rti.org.tw/news/view/id/2054821|script-title=zh:中國在西藏地區軍演頻繁 牽動中印未來危機應對|date=10 March 2020|access-date=16 May 2020|language=zh-tw|editor=Chang Ya-Han {{lang|zh-tw|張雅涵}}|work=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200311153414/https://www.rti.org.tw/news/view/id/2054821|archive-date=11 March 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The Indian position, as stated by Prime Minister Nehru, was that the Aksai Chin was "part of the Ladakh region of India for centuries" and that this northern border was a "firm and definite one which was not open to discussion with anybody".<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> | |||

| A continued face-off in the ] of May and June 2020 between Indian and Chinese troops near Pangong Tso Lake culminated in a violent clash on 16 June 2020, with at least 20 deaths from the Indian side and no official reported deaths from the Chinese side. In 2021, Chinese state media reported 4 Chinese deaths.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2021-02-19 |title=Ladakh: China reveals soldier deaths in India border clash |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56121781 |access-date=2022-02-26}}</ref> Both sides claimed provocation from the other.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-china-border-tensions-live-updates-at-least-20-indian-soldiers-killed-in-violent-face-off-with-china/liveblog/76396873.cms|title = India China news live: At least 20 Indian Army personnel killed in violent face-off in Ladakh's Galwan Valley|website = ]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indian-chinese-troops-face-off-in-eastern-ladakh-sikkim/article31548893.ece|title=Indian, Chinese troops face off in Eastern Ladakh, Sikkim|work=]|author=Dinakar Peri|date=10 May 2020|access-date=13 May 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200512053057/https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indian-chinese-troops-face-off-in-eastern-ladakh-sikkim/article31548893.ece|archive-date=12 May 2020|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="hket">{{cite web|url=https://china.hket.com/article/2639292/中印邊境再爆衝突%20%20150士兵毆鬥釀12傷|script-title=zh:中印邊境再爆衝突 150士兵毆鬥釀12傷|language=zh-hant|date=11 May 2020|access-date=16 May 2020|work=]|author={{lang|zh-hant|費風}}|quote={{lang|zh-hant|消息指,第一起事件發生於5月5日至6日,在中印邊境的班公錯湖(Pangong Tso )地區,當時解放軍的「侵略性巡邏」(aggressive patrolling)被印度軍方阻攔。「結果發生了混亂,雙方都有一些士兵受傷。」{...}2017年8月,兩國軍隊曾於拉達克地區班公湖附近爆發衝突,當時雙方擲石攻擊對方,雙方均有人受傷,最終兩軍在半小時後退回各自據點。}}}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/chinese-military-bolsters-troops-in-aksai-chin-region-in-sino-india-border-report/articleshow/75810930.cms|title=Chinese military bolsters troops in Aksai Chin region in Sino-India border: Report|date=19 May 2020|access-date=19 May 2020|work=]|quote=On May 5, around 250 Indian and Chinese army personnel clashed in Pangong Tso lake area in Eastern Ladakh.|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200519125336/https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/chinese-military-bolsters-troops-in-aksai-chin-region-in-sino-india-border-report/articleshow/75810930.cms|archive-date=19 May 2020|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3940166|title=Chinese, Indian troops engage in border conflicts|date=25 May 2020|access-date=26 May 2020|website=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/india-southchinasea-05222020182130.html|title=India Voices Unusual Criticism of China's Conduct in South China Sea|date=22 May 2020|access-date=27 May 2020|work=]|author=Drake Long|quote=Chinese and Indian troops clashed on May 5 over road construction the Indian side was completing at Pangong Tso, a glacial lake bordering Ladakh and Tibet.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/32699/Transcript_of_Media_Briefing_by_Official_Spokesperson_May_21_2020|title=Transcript of Media Briefing by Official Spokesperson (May 21, 2020)|date=21 May 2020|access-date=27 May 2020|work=]}}</ref> | |||

| The Chinese minister ] argued that the western border had never been delimited, that the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Aksai Chin within Chinese borders was the only line ever proposed to a Chinese government, and that the Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction, and that negotiations should take into account the status quo.<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| === Trans Karakoram Tract === | |||

| {{see also|List of locations in Aksai Chin}} | |||

| {{main|Trans Karakoram Tract}} | |||

| ] map of the western Indo-Chinese border, showing Aksai Chin and other contested territories]] | |||

| The Johnson Line is not used west of the ], where China adjoins Pakistan-administered ]. On October 13, 1962, China and Pakistan began negotiations over the boundary west of the Karakoram Pass. In 1963, the two countries settled their boundaries largely on the basis of the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Trans Karakoram Tract in China, although the agreement provided for renegotiation in the event of a settlement of the ]. India does not recognise that Pakistan and China have a common border, and claims the tract as part of the domains of the pre-1947 state of Kashmir and Jammu. However, presently the government of India's claim line in that area does not extend as far north of the Karakoram Mountains as the Johnson Line<ref name="Neville_Maxwell"/>. Though,the Constitution of India and the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir determine the territorial extent of Kashmir. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Aksai Chin is one of the two large disputed border areas between India and China. India claims Aksai Chin as the easternmost part of the union territory of ]. China claims that Aksai Chin is part of the ] and ]. The line that separates Indian-administered areas of ] from Aksai Chin is known as the ] (LAC) and is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line. | |||

| The Aksai region is a ] with few settlements such as ], ], ] and ] and ] which lays north of it, with the latter being the forward headquarters of the Xinjiang Military Command during the ]. | |||

| ==Strategic importance== | |||

| ] runs through Aksai Chin connecting ] and ] in the ]. Despite this region being nearly uninhabitable and having no resources, it remains strategically important for China as it connects both region. Construction started in 1951 and the road was completed in 1957. The construction of this highway was one of the triggers for the ] of 1962.{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} | |||

| Aksai Chin covers an area of approximately {{convert|38000|km2|mi2}}.<ref name=area>{{Cite encyclopedia| year = 2013| encyclopedia = ]| title = Aksai Chin| url= https://www.britannica.com/place/Aksai-Chin| access-date=11 June 2021|quote = At the conclusion of the conflict, China retained control of about 14,700 square miles (38,000 square km) of territory in Aksai Chin.}}</ref> The area is largely a vast high-altitude ] with a low point (on the '']'') at about {{convert|4300|m|abbr=on}} above sea level. In the southwest, mountains up to {{convert|7000|m|abbr=on}} extending southeast from the ] form the ''de facto'' border (Line of Actual Control) between Aksai Chin and Indian-controlled Kashmir. | |||

| ==Chinese terrain model== | |||

| In June 2006, ] on the ] service revealed a 1:500<ref name="age"/> scale terrain model of eastern Aksai Chin and adjacent Tibet, built near the town of ], about {{convert|35|km}} southwest of ], the capital of the autonomous region of ] in China.<ref></ref> A visual side-by-side comparison shows a very detailed duplication of Aksai Chin in the camp.<ref>, 10 April 2007</ref> The {{convert|900|x|700|m|abbr=on}}{{Citation needed|reason=source "age" claims 3km!|date=July 2009}} model was surrounded by a substantial facility, with rows of red-roofed buildings, scores of olive-colored trucks and a large compound with elevated lookout posts and a large communications tower. Such terrain models are known to be used in military training and simulation, although usually on a much smaller scale. | |||