| Revision as of 06:43, 28 April 2020 view sourceDr.K. (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers110,824 edits Reverted 1 edit by TR34Istanbul (talk): Per Khirurg's comment. Irrelevant for this section. (TW★TW)Tag: Undo← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:17, 31 December 2024 view source Zahirulnukman (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users800 editsm updateNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Country in West Asia and Southeast Europe}} | ||

| {{ |

{{About|the country|the bird|Turkey (bird)||Turkey (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{Redirect|Türkiye}} | |||

| {{redir|Türkiye|the newspaper|Türkiye (newspaper)}} <!-- Here add only the other articles titled Türkiye --> | |||

| {{pp- |

{{pp-move}} | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{Use |

{{Use American English|date=February 2023}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox country | {{Infobox country | ||

| | conventional_long_name |

| conventional_long_name = Republic of Türkiye | ||

| | common_name = Turkey <!-- DO NOT change to Türkiye. The subject of Turkey's name rebrand is controversial, and there is currently no consensus on Misplaced Pages supporting the use of Türkiye in English text. --> | |||

| | common_name = Turkey | |||

| | native_name |

| native_name = {{native name|tr|Türkiye Cumhuriyeti}} | ||

| | image_flag |

| image_flag = Flag of Turkey.svg | ||

| | image_coat |

| image_coat = <!-- The Turkish Constitution doesn't specify an official coat of arms --> | ||

| | |

| symbol_type = | ||

| | national_motto = <!-- The Turkish Constitution doesn't specify an official motto --> | |||

| | national_anthem |

| national_anthem = <br />{{lang|tr|]}}<br />"Independence March"<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.mfa.gov.tr/the-turkish-flag-and-the-turkish-national-anthem.en.mfa |title=The Turkish Flag and The Turkish National Anthem (Independence March) |website=Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Foreign Affairs |access-date=4 August 2024}}</ref>{{parabr}}{{center|]}}<!-- Do not replace this with the instrumental version. Official sheet music provided by the source contains lyrics.--> | ||

| | image_map |

| image_map = Turkey (orthographic projection).svg | ||

| | capital |

| capital = ] | ||

| | coordinates |

| coordinates = {{Coord|39|55|N|32|51|E|type:city|display=title,inline}} | ||

| | largest_city |

| largest_city = ]<br />{{coord|41|1|N|28|57|E|display=inline}} | ||

| | official_languages = ]<ref name="TC Constituton Art. 3">{{cite news|title=Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası|url=https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/develop/owa/tc_anayasasi.maddeler?p3=3|publisher=]|access-date=1 July 2020|language=Tr|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200702232731/https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/develop/owa/tc_anayasasi.maddeler?p3=3|archive-date=2 July 2020|quote="3. Madde: Devletin Bütünlüğü, Resmi Dili, Bayrağı, Milli Marşı ve Başkenti: Türkiye Devleti, ülkesi ve milletiyle bölünmez bir bütündür. Dili Türkçedir. Bayrağı, şekli kanununda belirtilen, beyaz ay yıldızlı al bayraktır. Milli marşı "İstiklal Marşı" dır. Başkenti Ankara'dır."}}</ref><ref name="Constitutional Court of Turkey - Constitution Art. 3">{{cite news|title=Mevzuat: Anayasa|url=https://www.anayasa.gov.tr/tr/mevzuat/anayasa/|publisher=]|access-date=1 July 2020|language=Tr|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200621023406/https://www.anayasa.gov.tr/tr/mevzuat/anayasa/|archive-date=21 June 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | official_languages = ] | |||

| | languages_type |

| languages_type = ]s | ||

| | languages = {{vunblist | |||

| | languages = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | Predominantly Turkish<ref> | |||

| | ethnic_groups = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|KONDA|2006|p=19}} | |||

| | demonym = {{hlist|]}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Kornfilt|2018|p=537}}</ref>}} {{collapsible list |]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | government_type = ] ] ] ] | |||

| | |

| ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list | ||

| | 70–75% ] | |||

| | leader_name1 = ] | |||

| | |

| 19% ] | ||

| | 6–11% ] | |||

| | leader_name2 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | leader_title3 = ] | |||

| | |

| demonym = {{hlist|Turkish|Turk}} | ||

| | government_type = Unitary ] | |||

| | legislature = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| | |

| leader_title1 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_name1 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_title2 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_name2 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_title3 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_name3 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_title4 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_name4 = ] | ||

| | |

| legislature = {{nowrap|]}} | ||

| | established_event1 = ] | |||

| | established_date5 = 7 November 1982 | |||

| | established_date1 = {{circa}} 1299 | |||

| | area_km2 = 783,356 <!--http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Aussenpolitik/Laender/Laenderinfos/01-Nodes_Uebersichtsseiten/Tuerkei_node.html --> | |||

| | sovereignty_type = ] | |||

| | area_rank = 36th | |||

| | established_event2 = ] | |||

| | area_sq_mi = 302535 <!--Do not remove per ]--> | |||

| | |

| established_date2 = 19 May 1919 | ||

| | established_event3 = ] | |||

| | population_estimate = {{increase}} 83,154,997<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=33705 |title=Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Kayıt Sistemi Sonuçları, 2019 |trans-title=The Results of Address-Based Population Recording System, 2019 |website=Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu |trans-website=] |date=4 February 2020 |access-date=23 March 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | established_date3 = 23 April 1920 | |||

| | population_estimate_rank = 18th | |||

| | established_event4 = ] | |||

| | population_estimate_year = 2019 | |||

| | established_date4 = 1 November 1922 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 105<ref name="Population density in Turkey">{{cite web|url=http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_id=1591|title=Annual growth rate and population density of provinces by years, 2007–2015|publisher=Turkish Statistical Institute|access-date=10 November 2016}}</ref> | |||

| | established_event5 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 262 | |||

| | established_date5 = 24 July 1923 | |||

| | population_density_rank = 107th | |||

| | established_event6 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| | GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $2.464 trillion<ref name=IMF-WEO>{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=48&pr.y=15&sy=2017&ey=2021&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=186&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPPC&grp=0&a= |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019 |publisher=] |website=IMF.org |access-date=26 January 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | |

| established_date6 = 29 October 1923 | ||

| | established_event7 = ] | |||

| | GDP_PPP_rank = 13th | |||

| | |

| established_date7 = 9 November 1982<ref name="Constitution2019"/> | ||

| | area_km2 = 783,562 <!--http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Aussenpolitik/Laender/Laenderinfos/01-Nodes_Uebersichtsseiten/Tuerkei_node.html --> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 52nd | |||

| | |

| area_rank = 36th | ||

| | |

| area_sq_mi = 302535 <!--Do not remove per ]--> | ||

| | percent_water = 2.03<ref>{{cite web|title=Surface water and surface water change|access-date=11 October 2020|publisher=] (OECD)|url=https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SURFACE_WATER|archive-date=24 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210324133453/https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SURFACE_WATER|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | GDP_nominal_rank = 19th | |||

| | population_estimate = {{IncreaseNeutral}} 85,372,377<!-- Update all numbers using this source, including article body--><ref name="Population of Turkey">{{cite web |url=https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=The-Results-of-Address-Based-Population-Registration-System-2023-49684&dil=2 |title=The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2023 |publisher=] |website=www.tuik.gov.tr |date=6 February 2024 |access-date=6 February 2024 |archive-date=6 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240206082646/https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=The-Results-of-Address-Based-Population-Registration-System-2023-49684&dil=2 |url-status=live }}</ref> <!-- do not add update figure as that stat is only published once a year due to legal reasons --> | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{increase}} $9,683<ref name=IMF-WEO /> | |||

| | population_estimate_year = December 2023 | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 70th | |||

| | population_estimate_rank = 17th | |||

| | Gini = 43.0 <!--number only--> | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 111<ref name="Population of Turkey"/> | |||

| | Gini_year = 2017 | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 262 | |||

| | Gini_change = increase <!--increase/decrease/steady--> | |||

| | population_density_rank = 83rd | |||

| | Gini_ref = <ref>{{cite web |title=Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey |url=https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tessi190&plugin=1 |website=ec.europa.eu/eurostat |publisher=Eurostat |accessdate=13 February 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $3.457 trillion<ref name="IMFWEO.TR">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=186,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Türkiye) |publisher=] |website=www.imf.org |date=22 October 2024 |access-date=22 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | Gini_rank = 56th | |||

| | |

| GDP_PPP_year = 2024 | ||

| | GDP_PPP_rank = 12th | |||

| | HDI_year = 2018<!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $40,283<ref name="IMFWEO.TR" /> | |||

| | HDI_change = increase<!--increase/decrease/steady--> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 54th | |||

| | HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web |url=http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf |title=2019 Human Development Report |year=2019 |accessdate=9 December 2019 |publisher=United Nations Development Programme }}</ref> | |||

| | |

| GDP_nominal = {{increase}} $1.344 trillion<ref name="IMFWEO.TR" /> | ||

| | GDP_nominal_year = 2024 | |||

| | currency = ] ] | |||

| | |

| GDP_nominal_rank = 17th | ||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{increase}} $15,666<ref name="IMFWEO.TR" /> | |||

| | time_zone = ] | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 64th | |||

| | utc_offset = +3 | |||

| | |

| Gini = 41.9 <!--number only--> | ||

| | |

| Gini_year = 2019 | ||

| | Gini_ref = <ref name="Gini">{{cite web|url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=TR|title=Gini index (World Bank estimate) – Turkey|year=2019|access-date=15 November 2021|publisher=World Bank|archive-date=17 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190517075906/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI%3Flocations%3DTR|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | calling_code = ] | |||

| | |

| Gini_change = steady <!--increase/decrease/steady--> | ||

| | |

| HDI = 0.855 <!--number only--> | ||

| | HDI_year = 2022<!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> | |||

| | religion = ]<ref>{{Cite book|title=Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası|publisher=Republic of Turkey|year=2018|isbn=|location=|chapter=Madde 2|lang=tr}}</ref><br>(see ]) | |||

| | |

| HDI_change = increase<!--increase/decrease/steady--> | ||

| | HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web |url=https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI |title=Human Development Index (HDI) |publisher=] |access-date=18 March 2024 |archive-date=10 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220610040330/https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | HDI_rank = 45th | |||

| | currency = ] (]) | |||

| | currency_code = TRY | |||

| | time_zone = ] | |||

| | utc_offset = +3 | |||

| | calling_code = ] | |||

| | cctld = ] | |||

| | today = | |||

| | ethnic_groups_year = 2016 | |||

| | ethnic_groups_ref = <ref name="cia">{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/turkey-turkiye/#people-and-society |title=Turkey (Turkiye) |work=] |publisher=] |access-date=19 May 2024}}</ref> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

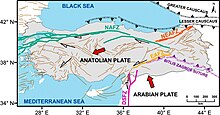

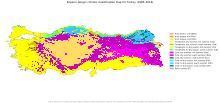

| '''Turkey''',{{efn|{{langx|tr|Türkiye}}, {{IPA|tr|ˈtyɾcije|lang}}}}<!--NOTE: Do not change lead sentence to Türkiye per ]. Thanks.--> officially the '''Republic of Türkiye''',{{efn|{{langx|tr|Türkiye Cumhuriyeti}}, {{IPA|tr|ˈtyɾcije dʒumˈhuːɾijeti|lang|Tur-Türkiye_Cumhuriyeti.ogg}}}} is a country mainly located in ] in ], with a smaller part called ] in ]. It borders the ] to the north; ], ], ], and ] to the east; ], ], and the ] to the south; and the ], ], and ] to the west. Turkey is home to over 85 million people; most are ethnic ], while ethnic ] are the ].<ref name="cia"/> Officially ], Turkey has ] population. ] is Turkey's capital and ], while ] is its largest city and economic and financial center. Other major cities include ], ], and ]. | |||

| Turkey was first inhabited by modern humans during the ].<ref>{{harvnb| Howard|2016|p=24}}</ref> Home to important ] sites like ] and some of the ], present-day Turkey was inhabited by ].<ref> | |||

| '''Turkey''' ({{lang-tr|Türkiye}} {{IPA-tr|ˈtyɾcije|}}), officially the '''Republic of Turkey''' ({{lang-tr|Türkiye Cumhuriyeti|links=no}} {{IPA-tr|ˈtyɾcije dʒumˈhuːɾijeti||Tur-Türkiye_Cumhuriyeti.ogg}}), is a ] country located mainly on the ] in ], with a smaller portion on the ] in ]. ], the part of Turkey in Europe, is separated from Anatolia by the ], the ] and the ] (collectively called the ]).<ref name="NatlGeoAtlas2">{{cite book|title=National Geographic Atlas of the World|publisher=National Geographic|year=1999|isbn=978-0-7922-7528-2|edition=7th|location=Washington, DC}} "Europe" (pp. 68–69); "Asia" (pp. 90–91): "A commonly accepted division between Asia and Europe ... is formed by the Ural Mountains, Ural River, Caspian Sea, Caucasus Mountains, and the Black Sea with its outlets, the Bosporus and Dardanelles."</ref> ], which straddles Europe and Asia, is the largest city in the country while ] is the ]. Turkey is bordered on its northwest by ] and ]; north by the ]; northeast by ]; east by ], the ]i ] of ] and ]; southeast by ] and ]; south by the ]; and west by the ]. Approximately 70 to 80 percent of the country's citizens identify as ],<ref name="konda2">{{cite web |url=http://www.konda.com.tr/tr/raporlar/2006_09_KONDA_Toplumsal_Yapi.pdf |title=Toplumsal Yapı Araştırması 2006 |date=2006 |publisher=] |access-date=21 February 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170215004933/http://www.konda.com.tr/tr/raporlar/2006_09_KONDA_Toplumsal_Yapi.pdf |archive-date=15 February 2017 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="cia2">{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html |title=Turkey|work=The World Factbook |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency]] |access-date=13 October 2016}}</ref> while ] are the largest minority at anywhere from 15 to 20 percent of the population. | |||

| * {{harvnb|Howard|2016|pp=24–28}}: "Göbekli Tepe’s close proximity to several very early sites of grain cultivation helped lead Schmidt to the conclusion that it was the need to maintain the ritual center that first encouraged the beginnings of settled agriculture—the Neolithic Revolution" | |||

| * {{harvnb|McMahon|Steadman|2012a|pp=3–12}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Matthews|2012|p=49}}</ref> The ] were assimilated by the ], such as the ].<ref> | |||

| * {{harvnb|Ahmed|2006|p=1576}}: "Turkey’s diversity is derived from its central location near the world’s earliest civilizations as well as a history replete with population movements and invasions. The Hattite culture was prominent during the Bronze Age prior to 2000 BCE, but was replaced by the Indo-European Hittites who conquered Anatolia by the second millennium. Meanwhile, Turkish Thrace came to be dominated by another Indo-European group, the Thracians for whom the region is named." | |||

| * {{harvnb|Steadman|2012|p=234}}: "By the time of the Old Assyrian Colony period in the early second millennium b.c.e . (see Michel, chapter 13 in this volume) the languages spoken on the plateau included Hattian, an indigenous Anatolian language, Hurrian (spoken in northern Syria), and Indo-European languages known as Luwian, Hittite, and Palaic" | |||

| * {{harvnb|Michel|2012|p=327}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Melchert|2012|p=713}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=26}}</ref> ] transitioned into cultural ] following the conquests of ]; Hellenization continued during the ] and ] eras.<ref> | |||

| * {{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=29}}: "The sudden disappearance of the Persian Empire and the conquest of virtually the entire Middle Eastern world from the Nile to the Indus by Alexander the Great caused tremendous political and cultural upheaval. ... statesmen throughout the conquered regions attempted to implement a policy of Hellenization. For indigenous elites, this amounted to the forced assimilation of native religion and culture to Greek models. It met resistance in Anatolia as elsewhere, especially from priests and others who controlled temple wealth." | |||

| * {{harvnb|Ahmed|2006|p=1576}}: "Subsequently, hellenization of the elites transformed Anatolia into a largely Greek-speaking region" | |||

| * {{harvnb|McMahon|Steadman|2012a|p=5}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|McMahon|2012|p=16}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Sams|2012|p=617}}</ref> The ] began migrating into Anatolia in the 11th century, starting the ] process.<ref> | |||

| * {{harvnb|Davison|1990|pp=3–4}}: "So the Seljuk sultanate was a successor state ruling part of the medieval Greek empire, and within it the process of Turkification of a previously Hellenized Anatolian population continued. That population must already have been of very mixed ancestry, deriving from ancient Hittite, Phrygian, Cappadocian, and other civilizations as well as Roman and Greek." | |||

| * {{harvnb|Howard|2016|pp=33–44}}</ref> The Seljuk ] ruled Anatolia until the ] in 1243, when it disintegrated into ].<ref name="Howard 2016 38–39">{{harvnb|Howard|2016|pp=38–39}}</ref> Beginning in 1299, the ] united the principalities and ]. ] conquered ]. During the reigns of ] and ], the Ottoman Empire became a ].<ref name=Howard_p45>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=45}}</ref><ref name=Somel_p_xcvii>{{harvnb|Somel|2010|p=xcvii}}</ref> From 1789 onwards, the empire saw ], ], and centralization while ].<ref> | |||

| * {{harvnb|Hanioğlu|2012|pp=15–25}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Kayalı|2012|pp=26–28}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|Davison|1990|pp=115–116}}</ref> | |||

| In the 19th and early 20th centuries, ] and ] resulted in large-scale loss of life and ] from the ], ], and ].<ref> | |||

| At various points in its history, the region has been inhabited by diverse civilisations including the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Howard2">{{Cite book| publisher = Greenwood Publishing Group| isbn = 978-0-313-30708-9| last = Howard| first = Douglas Arthur| title = The History of Turkey| date = 2001 |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofturkey00doug| url-access = registration| page = }}</ref><ref name="SteadmanMcMahon20112">{{cite book|url={{Google books |plainurl=yes |id=7ND_CE9If3kC }}|title=The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000–323 BC)|author1=Sharon R. Steadman|author2=Gregory McMahon|year=2011|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-537614-2|pages=3–11, 37|access-date=23 March 2013}}</ref><ref name="MET">{{cite journal|last=Casson|first=Lionel|year=1977|title=The Thracians|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3258667.pdf.bannered.pdf|journal=The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin|volume=35|issue=1|pages=2–6|doi=10.2307/3258667|jstor=3258667}}</ref> ] started during the era of ] and continued into the ].<ref name="SteadmanMcMahon20112" /><ref name="FreedmanMyers20002">{{cite book|url={{Google books |plainurl=yes |id=P9sYIRXZZ2MC |page=61 }}|title=Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible|author1=David Noel Freedman|author2=Allen C. Myers|author3=Astrid Biles Beck|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year=2000|isbn=978-0-8028-2400-4|page=61|access-date=24 March 2013}}</ref> The ] began migrating into the area in the 11th century, and their victory over the Byzantines at the ] in 1071 symbolises the foundation of Turkey.<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = Springer| isbn = 978-1-137-33421-3| last1 = Gürpinar| first1 = D.| last2 = Gürpinar| first2 = Dogan| title = Ottoman/Turkish Visions of the Nation, 1860–1950|year=2013}}</ref> The ] ruled Anatolia until the ] in 1243, when it disintegrated into small principalities called ].<ref name="mfk&gl2">{{cite book|title=The origins of the Ottoman Empire|last1=Mehmet Fuat Köprülü&Gary Leiser|page=33}}</ref> Beginning in the late 13th century, the ] started ]. After ] conquered ] in 1453, Ottoman expansion continued under ]. During the reign of ] the ] encompassed much of Southeast Europe, West Asia and ] and became a ].<ref name=Howard2/><ref name=masters>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=4x09OvMBMmgC&pg=PA17&dq=%22ottoman+empire%22+%22world+power%22#v=onepage&q=%22ottoman%20empire%22%20%22world%20power%22&f=false|title=The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516–1918: A Social and Cultural History|last=Masters|first=Bruce|year=2013|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-03363-4|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=UU8iCY0OZmcC&pg=PR97&dq=Ottoman+empire+world+power+suleyman#v=onepage&q=Ottoman%20empire%20world%20power%20suleyman&f=false|title=The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire|last=Somel|first=Selcuk Aksin|year=2010|publisher=Scarecrow Press|isbn=978-1-4617-3176-4|language=en}}</ref> From the late 18th century onwards, the ] with a gradual loss of territories and wars.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=VDm769--fZQC&pg=PA51&dq=the+ottoman+empire+started+to+decline#v=onepage&q=the%20ottoman%20empire%20started%20to%20decline&f=false|title=Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire: A Contribution to the History of the Balkans|last=Marushiakova|first=Elena|last2=Popov|first2=Veselin Zakhariev|last3=Popov|first3=Veselin|last4=Descartes)|first4=Centre de recherches tsiganes (Université René|date=2001|publisher=Univ of Hertfordshire Press|isbn=978-1-902806-02-0|language=en}}</ref> In an effort to consolidate the weakening social and political foundations of the empire, ] started a ] in the early 19th century, bringing reforms in all areas of the state including the military and bureaucracy, along with the emancipation of all citizens.<ref>Roderic. H. Davison, Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774-1923 – The Impact of West, Texas 1990, pp. 115-116.</ref> | |||

| * {{harvnb|Kaser|2011|p=336}}: "The emerging Christian nation states justified the prosecution of their Muslims by arguing that they were their former “suppressors”. The historical balance: between about 1820 and 1920, millions of Muslim casualties and refugees back to the remaining Ottoman Empire had to be registered; estimations speak about 5 million casualties and the same number of displaced persons" | |||

| * {{harvnb|Fábos|2005|p=437}}: "Muslims had been the majority in Anatolia, the Crimea, the Balkans, and the Caucasus and a plurality in southern Russia and sections of Romania. Most of these lands were within or contiguous with the Ottoman Empire. By 1923, 'only Anatolia, eastern Thrace, and a section of the southeastern Caucasus remained to the Muslim land ... Millions of Muslims, most of them Turks, had died; millions more had fled to what is today Turkey. Between 1821 and 1922, more than five million Muslims were driven from their lands. Five and one-half million Muslims died, some of them killed in wars, others perishing as refugees from starvation and disease' (McCarthy 1995, 1). Since people in the Ottoman Empire were classified by religion, Turks, Albanians, Bosnians, and all other Muslim groups were recognized—and recognized themselves—simply as Muslims. Hence, their persecution and forced migration is of central importance to an analysis of 'Muslim migration.'" | |||

| * {{harvnb|Karpat|2001|p=343}}: "The main migrations started from Crimea in 1856 and were followed by those from the Caucasus and the Balkans in 1862 to 1878 and 1912 to 1916. These have continued to our day. The quantitative indicators cited in various sources show that during this period a total of about 7 million migrants from Crimea, the Caucasus, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean islands settled in Anatolia. These immigrants were overwhelmingly Muslim, except for a number of Jews who left their homes in the Balkans and Russia in order to live in the Ottoman lands. By the end of the century the immigrants and their descendants constituted some 30 to 40 percent of the total population of Anatolia, and in some western areas their percentage was even higher." ... "The immigrants called themselves Muslims rather than Turks, although most of those from Bulgaria, Macedonia, and eastern Serbia descended from the Turkish Anatolian stock who settled in the Balkans in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries." | |||

| * {{harvnb|Karpat|2004|pp=5–6}}: "Migration was a major force in the social and cultural reconstruction of the Ottoman state in the nineteenth century. While some seven to nine million, mostly Muslim, refugees from lost territories in the Caucasus, Crimea, Balkans and Mediterranean islands migrated to Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, during the last quarter of the nineteenth and the early part of the twentieth centuries..." | |||

| * {{harvnb|Pekesen|2012}}: "The immigration had far-reaching social and political consequences for the Ottoman Empire and Turkey." ... "Between 1821 and 1922, some 5.3 million Muslims migrated to the Empire.50 It is estimated that in 1923, the year the republic of Turkey was founded, about 25 per cent of the population came from immigrant families.51" | |||

| * {{harvnb|Biondich|2011|p=93}}: "The road from Berlin to Lausanne was littered with millions of casualties. In the period between 1878 and 1912, as many as two million Muslims emigrated voluntarily or involuntarily from the Balkans. When one adds those who were killed or expelled between 1912 and 1923, the number of Muslim casualties from the Balkan far exceeds three million. By 1923 fewer than one million remained in the Balkans" | |||

| * {{harvnb|Armour|2012|p=213}}: "To top it all, the Empire was host to a steady stream of Muslim refugees. Russia between 1854 and 1876 expelled 1.4 million Crimean Tartars, and in the mid-1860s another 600,000 Circassians from the Caucasus. Their arrival produced further economic dislocation and expense." | |||

| * {{harvnb|Bosma|Lucassen|Oostindie|2012a|p=17}}: "In total, many millions of Turks (or, more precisely, Muslim immigrants, including some from the Caucasus) were involved in this ‘repatriation’ – sometimes more than once in a lifetime – the last stage of which may have been the immigration of seven hundred thousand Turks from Bulgaria between 1940 and 1990. Most of these immigrants settled in urban north-western Anatolia. Today between a third and a quarter of the Republic’s population are descendants of these Muslim immigrants, known as Muhacir or Göçmen"</ref> Under the control of the ], the Ottoman Empire ] in 1914, during which the Ottoman government committed ] against its ], ], and ] subjects.<ref name="Tatz">{{Cite book| publisher = ABC-CLIO| isbn = 978-1-4408-3161-4| last1 = Tatz| first1 = Colin| last2 = Higgins| first2 = Winton| title = The Magnitude of Genocide| year=2016}}</ref><ref name="SchallerZimmerer">{{Cite journal|last1=Schaller|first1=Dominik J.|last2=Zimmerer|first2=Jürgen|s2cid=71515470|year=2008|title=Late Ottoman genocides: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies – introduction|journal=Journal of Genocide Research|volume=10|issue=1|pages=7–14|doi=10.1080/14623520801950820|issn=1462-3528}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Morris |first1=Benny |title=The Thirty-Year Genocide - Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924 |last2=Ze'evi |first2=Dror |publisher=] |year=2021 |isbn=9780674251434}}</ref> Following Ottoman defeat, the ] resulted in the ] and the signing of the ]. The Republic ] on 29 October 1923, modelled on ] initiated by the country's first president, ]. Turkey ], but was involved in the ]. Several military interventions interfered with the transition to a multi-party system. | |||

| Turkey is an ] and ]; ] is the world's ] and ]. It is a ] presidential ]. Turkey is a founding member of the ], ], and ]. With a geopolitically significant location, Turkey is a ]<ref name="giga-hamburg.de1">{{cite web|url=http://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/system/files/publications/wp204_bank-karadag.pdf|title=The Political Economy of Regional Power: Turkey|website=giga-hamburg.de|access-date=18 February 2015|archive-date=10 February 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140210210237/http://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/system/files/publications/wp204_bank-karadag.pdf}}</ref> and an early member of ]. ], Turkey is part of the ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| The ] effectively put the country under the control of the ], who were largely responsible for the Empire's ] on the side of the ] in 1914. During ], the Ottoman government committed ] against its ], ] and ] subjects.{{efn-ur|name=two|Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said "Our attitude on the Armenian issue has been clear from the beginning. We will never accept the accusations of genocide".<ref>{{Cite web |website= Deutsche Welle |title= Erdogan: Turkey will 'never accept' genocide charges |accessdate= 7 February 2018 |url= http://www.dw.com/en/erdogan-turkey-will-never-accept-genocide-charges/a-19307115}}</ref> Scholars give several reasons for Turkey's ] including the preservation of national identity, the demand for reparations and territorial concerns.<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = ABC-CLIO| isbn = 978-1-4408-3161-4| last1 = Tatz| first1 = Colin| last2 = Higgins| first2 = Winton| title = The Magnitude of Genocide| year=2016}}</ref>}}<ref name="SchallerZimmerer">{{Cite journal|last=Schaller|first=Dominik J.|last2=Zimmerer|first2=Jürgen|year=2008|title=Late Ottoman genocides: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies—introduction|url=|journal=Journal of Genocide Research|volume=10|issue=1|pages=7–14|doi=10.1080/14623520801950820|issn=1462-3528}}</ref> After the Ottomans lost the war, the conglomeration of territories and peoples that had composed the Ottoman Empire was ].<ref>]; Review "From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920" by Paul C. Helmreich in '']'', Vol. 34, No. 1 (March 1975), pp. 186–187</ref> The ], initiated by ] and his comrades against the occupying ], resulted in the ] on 1 November 1922, the replacement of the ] (1920) with the ] (1923), and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923, with Atatürk as its first president.<ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|url= http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-44425/Turkey|title=Turkey, Mustafa Kemal and the Turkish War of Independence, 1919–23|access-date=29 October 2007|year=2007}}</ref> Atatürk enacted ], many of which incorporated various aspects of ] thought, philosophy and customs into the new form of Turkish government.<ref>S.N. Eisenstadt, "The Kemalist Regime and Modernization: Some Comparative and Analytical Remarks," in J. Landau, ed., Atatürk and the Modernisation of Turkey, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1984, 3–16.</ref> | |||

| Turkey has coastal plains, ], and various mountain ranges; ] is temperate with harsher conditions in the interior.<ref name="CIA_geo">{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/turkey-turkiye/#geography |title=Turkey |work=] |publisher=] |access-date=29 February 2024 |archive-date=28 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220828085706/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/turkey-turkiye/#geography |url-status=live }}</ref> Home to three ]s,<ref name="Birben_2019">{{cite journal |last1=Birben |first1=Üstüner |date=2019 |title=The Effectiveness of Protected Areas in Biodiversity Conservation: The Case of Turkey |journal=CERNE |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=424–438 |doi=10.1590/01047760201925042644 |quote=Turkey has 3 out of the 36 biodiversity hotspots on Earth: the Mediterranean, Caucasus, and Irano-Anatolian hotspots|doi-access=free | issn = 0104-7760 }}</ref> Turkey is prone to ] and ].<ref name="Ahmed_2006_pp_1575_1576">{{harvnb|Ahmed|2006|pp=1575–1576}}</ref><ref name="World_Bank_climate_change">{{harvnb|World Bank Türkiye - Country Climate and Development Report|2022|p=7}}</ref> Turkey has ], growing ], and increasing levels of ].<ref> | |||

| Turkey is a charter member of the ], an early member of ], the ], and the ], and a founding member of the ], ], ], ], and ]. After becoming ] of the ] in 1949, Turkey became an ] of the ] in 1963, joined the ] in 1995, and started ] with the ] in 2005. In a non-binding vote on 13 March 2019, the ] called on the EU governments to suspend Turkey's accession talks; which, despite being stalled since 2018, remain active as of 2020.<ref name="dw-13-03-2019">{{Cite web|url=https://www.dw.com/en/european-parliament-votes-to-suspend-turkeys-eu-membership-bid/a-47902275|title=European Parliament votes to suspend Turkey's EU membership bid|publisher=Deutsche Welle|website=www.dw.com|language=en-GB|date=13 March 2019|access-date=19 April 2020}}</ref> Turkey's economy and diplomatic initiatives have led to its recognition as a ], while its location has given it geopolitical and strategic importance throughout history.<ref name="giga-hamburg.de1">{{cite web|url=http://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/system/files/publications/wp204_bank-karadag.pdf|title=The Political Economy of Regional Power: Turkey|website=giga-hamburg.de|access-date=18 February 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |jstor=25642612|title=The Political and Strategic Importance of Turkey|journal=Bulletin of International News|volume=16|issue=22|pages=3–11|date=4 November 1939 |author1=M.B}}</ref> Turkey is a ], ], formerly ] that adopted a ] with a ]; the new system came into effect with the ]. Turkey's current administration, headed by President ] of the ], has enacted measures to increase the influence of ] and undermine ] policies and ].<ref>{{Cite news| issn = 0362-4331| last = Nordland| first = Rod| title = Turkey's Free Press Withers as Erdogan Jails 120 Journalists| work = The New York Times| accessdate = 24 April 2018| date = 17 November 2016| url = https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/18/world/europe/turkey-press-erdogan-coup.html}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news| issn = 0028-792X| last = Ackerman| first = Elliot| title = Atatürk Versus Erdogan: Turkey's Long Struggle| work = The New Yorker| accessdate = 24 April 2018| date = 16 July 2016| url = https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/ataturk-versus-erdogan-turkeys-long-struggle}}></ref> | |||

| * {{cite journal |doi=10.1056/NEJMp1410433 |title=Transforming Turkey's Health System — Lessons for Universal Coverage |date=2015 |last1=Atun |first1=Rifat |journal=New England Journal of Medicine |volume=373 |issue=14 |pages=1285–1289 |pmid=26422719}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|OECD Taking stock of education reforms for access and quality in Türkiye|2023|p=35}} | |||

| * {{harvnb|World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)|2024|p=22}}</ref> It is a leading ] exporter.<ref>{{cite book | last=Berg | first=Miriam | title=Turkish Drama Serials: The Importance and Influence of a Globally Popular Television Phenomenon | publisher=University of Exeter Press | year=2023 | isbn=978-1-80413-043-8 |pages=1–2}}</ref> With ] sites, 30 ] inscriptions,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.unesco.org/en/countries/tr |title=Türkiye |date= |website=UNESCO |access-date=2 March 2024 |archive-date=2 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240302171641/https://www.unesco.org/en/countries/tr |url-status=live }}</ref> and ],<ref name="Yayla_Aktaş_2021">{{cite journal |last1=Yayla |first1=Önder |last2=Aktaş |first2=Semra Günay |year=2021 |title=Mise en place for gastronomy geography through food: Flavor regions in Turkey |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1878450X21000834 |journal=International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science |volume=26 |doi=10.1016/j.ijgfs.2021.100384 |access-date=2 March 2024 |archive-date=2 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240302171641/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1878450X21000834 |url-status=live }}</ref> Turkey is the ] in the world. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| ''Turchia'', meaning "the land of the Turks", had begun to be used in European texts for ] by the end of the 12th century.<ref>{{harvnb|Agoston|Masters|2009|p=574}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=31}}</ref><ref name="Everett">{{harvnb|Everett-Heath|2020|loc=Türkiye (Turkey)}}</ref> As a word in ], ''Turk'' may mean "strong, strength, ripe" or "flourishing, in full strength".<ref>{{harvnb|Golden|2021|p=30}}</ref> It may also mean ripe as in for a fruit or "in the prime of life, young, and vigorous" for a person.<ref>{{harvnb|Clauson|1972|pp=542–543}}</ref> As an ], the etymology is still unknown.<ref>{{harvnb|Golden|2021|pp=6–7}}</ref> In addition to usage in languages such as Chinese in the 6th century,<ref name="Everett"/> the earliest mention of ''Turk'' ({{lang|otk|𐱅𐰇𐰺𐰜}}, {{transliteration|otk|türü̲k̲}}; or {{lang|otk|𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚}}, {{transliteration|otk|türk/tẄrk}}) in Turkic languages comes from the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Golden|2021|pp=9, 16}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Name of Turkey}} | |||

| The English name of Turkey (from ] ''Turchia''/''Turquia''<ref name=arlen>{{cite book|title=Passage to Ararat|author= Michael J. Arlen|publisher=MacMillan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-UahAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA159|page=159|year=2006|isbn= 978-0-374-53012-9}}</ref>) means "land of the Turks". ] usage of ''Turkye'' is evidenced in an early work by ] called '']'' (c. 1369). The phrase ''land of Torke'' is used in the 15th-century ]. Later usages can be found in the ], the 16th century '']'' ("Turkie, Tartaria") and ]'s ''Sylva Sylvarum'' (Turky). The modern spelling "Turkey" dates back to at least 1719.<ref>{{Cite OED|Turkey}}</ref> The ] name ''Türkiye'' was adopted in 1923 under the influence of European usage.<ref name="arlen" /> | |||

| In ] sources in the 10th century, the name '']'' was used for defining two medieval states: ] (''Western Tourkia''); and ] (''Eastern Tourkia'').<ref name="constantine_vii">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3al15wpFWiMC |title=De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus |last=Jenkins |first=Romilly James Heald |publisher=Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies |year=1967 |isbn=978-0-88402-021-9 |edition=New, revised |series=Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae |page=65 |access-date=28 August 2013 |archive-date=20 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230120171955/https://books.google.com/books?id=3al15wpFWiMC |url-status=live }} According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in his {{lang|la|]}} ({{circa|950 AD}}) "Patzinakia, the ], stretches west as far as the ] (or even the ]), and is four days distant from Tourkia ."</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Findley|2005|p=51}}</ref> The ], with its ruling elite of Turkic origin, was called the "State of the Turks" ({{transliteration|ar|Dawlat at-Turk}}, or {{transliteration|ar|Dawlat al-Atrāk}}, or {{transliteration|ar|Dawlat-at-Turkiyya}}).<ref>{{harvnb|Golden|2021|pp=2–3}}</ref> Turkestan, also meaning the "land of the Turks", was used for a historic region in ].<ref>{{harvnb|Everett-Heath|2020|loc=Turkestan, Central Asia, Kazakhstan}}</ref> | |||

| ] usage of {{lang|enm|Turkye}} or {{lang|enm|Turkeye}} is found in '']'' (written in 1369–1372) to refer to Anatolia or the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Gray|2003|loc=Turkye, (Turkeye) Turkey; Book of the Duchess, The; Map 1; Map 3}}.</ref> The modern spelling ''Turkey'' dates back to at least 1719.<ref>{{Cite OED|Turkey}}</ref> The ] was named as such due to trade of ] from Turkey to England.<ref name="Everett"/> The name ''Turkey'' has been used in international treaties referring to the Ottoman Empire.<ref> | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Hertslet |first=Edward |title=The Map of Europe by Treaty showing the various political and territorial changes which have taken place since the general peace of 1814, with numerous maps and notes |publisher=Butterworth |year=1875 |volume=2 |pages=1250–1265 |chapter=General treaty between Great Britain, Austria, France, Prussia, Russia, Sardinia and Turkey, signed at Paris on 30th March 1856}} | |||

| * {{cite web |url=https://archive.org/details/protocolsofconfe00grea/mode/2up |title=Protocols of conferences held at Paris relative to the general Treaty of Peace. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by command of Her Majesty, 1856 |publisher=Harrison |year=1856|access-date=9 May 2023}} | |||

| * {{Citation |last=Hertslet |first=Edward |author-link=Edward Hertslet |year=1891 |contribution=Treaty between Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Turkey, for the Settlement of Affairs in the East, Signed at Berlin, 13th July 1878 (Translation)|title= The Map of Europe by Treaty; which have taken place since the general peace of 1814. With numerous maps and notes |volume= IV (1875–1891) |edition=First |publisher=] |publication-date=1891 |pages=2759–2798 |url=https://archive.org/stream/mapofeuropebytre04hert#page/2758/mode/2up |access-date=9 May 2023 |via=]}} | |||

| *{{cite web|url=https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1878berlin.asp|title=Treaty Between Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Russia and Turkey. (Berlin). July 13, 1878.|website=sourcebooks.fordham.edu|access-date=9 May 2023|archive-date=26 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326061204/https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1878berlin.asp|url-status=live}}</ref> With the ], the name ''Türkiye'' entered international documents for the first time. In the treaty signed with ] in 1921, the expression {{transliteration|ota|Devlet-i Âliyye-i Türkiyye}} ("Sublime Turkish State") was used, likened to the ].<ref>{{TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi|title=Türkiye|author=Cevdet Küçük|page=567|volume=41}}</ref> | |||

| In December 2021, President ] called for expanded official usage of ''Türkiye'', saying that ''Türkiye'' "represents and expresses the culture, civilization, and values of the Turkish nation in the best way".<ref name="Genelge-2021/24">{{cite web|url=https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2021/12/20211204-5.pdf|title=Marka Olarak 'Türkiye' İbaresinin Kullanımı (Presidential Circular No. 2021/24 on the Use of the Term "Türkiye" as a Brand)|publisher=]|date=4 December 2021|access-date=11 April 2022|archive-date=17 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220517002246/https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2021/12/20211204-5.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> In May 2022, the Turkish government requested the ] and other international organizations to use ''Türkiye'' officially in English; the UN agreed.<ref>{{cite news |first=Ragip |last=Soylu |title=Turkey to register its new name Türkiye to UN in coming weeks |url=https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-turkiye-new-name-register-un-weeks |newspaper=] |date=17 January 2022 |access-date=11 April 2022 |archive-date=6 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220606203745/https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-turkiye-new-name-register-un-weeks |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2 June 2022 |title=UN to use 'Türkiye' instead of 'Turkey' after Ankara's request |url=https://www.trtworld.com/turkey/un-to-use-türkiye-instead-of-turkey-after-ankara-s-request-57633 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220602042921/https://www.trtworld.com/turkey/un-to-use-t%C3%BCrkiye-instead-of-turkey-after-ankara-s-request-57633 |archive-date=2 June 2022 |access-date=3 June 2022 |website=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Wertheimer |first=Tiffany |date=2 June 2022 |title=Turkey changes its name in rebranding bid |website=] |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-61671913 |url-status=live |access-date=2 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220602110511/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61671913 |archive-date=2 June 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Main|History of Turkey}} | {{Main|History of Turkey}} | ||

| {{see also|History of Anatolia|History of Thrace}} | {{see also|History of Anatolia|History of Thrace|Ancient regions of Anatolia}} | ||

| ===Prehistory |

===Prehistory and ancient history=== | ||

| {{Main|Prehistory of Anatolia|Prehistory of |

{{Main|Prehistory of Anatolia|Prehistory of Southeast Europe}} | ||

| {{ |

{{See also|Hattians|Hittites|Luwians|Pala (Anatolia)}} | ||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ]s at ] were erected as far back as ], predating those of ], ], by over seven millennia.<ref name="ArchMag" />]] | |||

| | align = right | |||

| ], capital of the ]. The city's history dates back to the 6th millennium BC.<ref name=whcunesco>{{cite web|title=Hattusha: the Hittite Capital|url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/377|website=whc.unesco.org|access-date=12 June 2014}}</ref>]] | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | total_width = 220 | |||

| | image1 = Göbekli Tepe, Urfa.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Some ]s at ] were erected as far back as ], predating those of ] by over seven millennia.<ref name="ArchMag">{{cite web|url=http://www.archaeology.org/0811/abstracts/turkey.html|title=The World's First Temple|work=Archaeology magazine|date=November–December 2008|page=23|access-date=25 July 2012|archive-date=29 March 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120329113052/http://www.archaeology.org/0811/abstracts/turkey.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | image2 = Sphinx_Gate,_Hattusa_01.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = The Sphinx Gate of ], the capital of the ]}} | |||

| Present-day Turkey has been inhabited by ] since the ] period and contains some of the world's oldest ] sites.<ref name="Howard 2016 24">{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=24}}</ref><ref name="MET">{{cite journal|last=Casson|first=Lionel|year=1977|title=The Thracians|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3258667.pdf.bannered.pdf|journal=The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin|volume=35|issue=1|pages=2–6|doi=10.2307/3258667|jstor=3258667|access-date=3 April 2013|archive-date=3 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190503015440/https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3258667.pdf.bannered.pdf}}</ref> ] is close to 12,000 years old.<ref name="Howard 2016 24"/> Parts of ] include the ], an ].<ref>{{harvnb|Bellwood|2022|p=224}}</ref> Other important Anatolian Neolithic sites include ] and ].<ref name="Howard 2016-3">{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=25}}</ref> Neolithic Anatolian farmers differed genetically from farmers in ] and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Bellwood|2022|p=229}}</ref> These early Anatolian farmers also ], starting around 9,000 years ago.<ref>{{harvnb|Bellwood|2022|p=229}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kılınç |first1=Gülşah Merve |last2=Omrak |first2=Ayça |last3=Özer |first3=Füsun |last4=Günther |first4=Torsten |last5=Büyükkarakaya |first5=Ali Metin |last6=Bıçakçı |first6=Erhan |last7=Baird |first7=Douglas |last8=Dönertaş |first8=Handan Melike |last9=Ghalichi |first9=Ayshin |last10=Yaka |first10=Reyhan |last11=Koptekin |first11=Dilek |last12=Açan |first12=Sinan Can |last13=Parvizi |first13=Poorya |last14=Krzewińska |first14=Maja |last15=Daskalaki |first15=Evangelia A. |date=June 2016 |title=The Demographic Development of the First Farmers in Anatolia |journal=Current Biology |language=en |volume=26 |issue=19 |pages=2659–2666 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.057 |pmc=5069350 |pmid=27498567|bibcode=2016CBio...26.2659K }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lipson |first1=Mark |last2=Szécsényi-Nagy |first2=Anna |last3=Mallick |first3=Swapan |last4=Pósa |first4=Annamária |last5=Stégmár |first5=Balázs |last6=Keerl |first6=Victoria |last7=Rohland |first7=Nadin |last8=Stewardson |first8=Kristin |last9=Ferry |first9=Matthew |last10=Michel |first10=Megan |last11=Oppenheimer |first11=Jonas |last12=Broomandkhoshbacht |first12=Nasreen |last13=Harney |first13=Eadaoin |last14=Nordenfelt |first14=Susanne |last15=Llamas |first15=Bastien |date=November 2017 |title=Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=551 |issue=7680 |pages=368–372 |doi=10.1038/nature24476 |issn=0028-0836 |pmc=5973800 |pmid=29144465|bibcode=2017Natur.551..368L }}</ref> ] earliest layers go back to around 4500 BC.<ref name="Howard 2016-3" /> | |||

| The Anatolian peninsula, comprising most of modern Turkey, is one of the oldest permanently settled regions in the world. Various ] populations have lived in ], from at least the ] until the ].<ref name="SteadmanMcMahon20112"/> Many of these peoples spoke the ], a branch of the larger ]:<ref name="UCLA">{{cite web|url=http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/The%20Position%20of%20Anatolian.pdf|archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/6GNtCVWdz?url=http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/The%20Position%20of%20Anatolian.pdf|archivedate=5 May 2013|title=The Position of Anatolian |access-date=4 May 2013}}</ref> and, given the antiquity of the Indo-European ] and ] languages, some scholars have proposed ].<ref name="AnatoliaIndoEuropean">{{Cite journal|last=Balter|first=Michael|title=Search for the Indo-Europeans: Were Kurgan horsemen or Anatolian farmers responsible for creating and spreading the world's most far-flung language family?|journal=Science|volume=303|issue=5662|page=1323|date=27 February 2004|doi=10.1126/science.303.5662.1323|pmid=14988549|url=https://semanticscholar.org/paper/df69fa5eb6d5a604e16aaf163cfb571d0206e34a}}</ref> The European part of Turkey, called ], has also been inhabited since at least forty thousand years ago, and is known to have been in the Neolithic era by about 6000 BC.<ref name="MET"/> | |||

| Anatolia's historical records start with ] from approximately around 2000 BC that were found in modern-day ].<ref name="Howard 2016-4">{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=26}}</ref> These tablets belonged to an ].<ref name="Howard 2016-4"/> The languages in Anatolia at that time included Hattian, Hurrian, ], ], and ].<ref name="McMahon_Steadman_2012_p_234">{{harvnb|Steadman|2012|p=234}}</ref> ] was a language indigenous to Anatolia, with no known modern-day connections.<ref name="McMahon_Steadman_2012_p_234"/><ref>{{harvnb|Michel|2012|p=327}}</ref> ] was used in northern ].<ref name="McMahon_Steadman_2012_p_234"/> Hittite, Palaic, and Luwian languages were "the oldest written ]",<ref>{{harvnb|Sagona|Zimansky|2015|p=246}}</ref> forming the ].<ref name="McMahon_Steadman_2012_p_522">{{harvnb|Beckman|2012|p=522}}</ref>{{efn|The origin of Indo-European languages is unknown.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030507 |title=Cognacy Databases and Phylogenetic Research on Indo-European |date=2021 |last1=Heggarty |first1=Paul |journal=Annual Review of Linguistics |volume=7 |pages=371–394}}</ref> ]<ref>{{harvnb|Bellwood|2022|p=242}}</ref> or non-native.<ref>{{harvnb|Melchert|2012|p=713}}</ref>}} | |||

| ] is the site of the oldest known man-made religious structure, a temple dating to circa 10,000 BC,<ref name="ArchMag">{{cite web|url=http://www.archaeology.org/0811/abstracts/turkey.html|title=The World's First Temple|work= Archaeology magazine |date=November–December 2008|page=23}}</ref> while ] is a very large Neolithic and ] settlement in southern Anatolia, which existed from approximately 7500 BC to 5700 BC. It is the largest and best-preserved Neolithic site found to date and is a ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://globalheritagefund.org/onthewire/blog/catalhoyuk_world_heritage_list |title=Çatalhöyük added to UNESCO World Heritage List |publisher=Global Heritage Fund |date=3 July 2012 |access-date=9 February 2013|url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130117025024/http://globalheritagefund.org/onthewire/blog/catalhoyuk_world_heritage_list |archivedate=17 January 2013}}</ref> The settlement of ] started in the Neolithic Age and continued into the ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Troy|url=http://www.ancient.eu/troy/|website=ancient.eu|access-date=9 August 2014}}</ref> | |||

| ] rulers were gradually replaced by ] rulers.<ref name="Howard 2016-4"/> The Hittite kingdom was a large kingdom in Central Anatolia, with its capital of ].<ref name="Howard 2016-4"/> It co-existed in Anatolia with ] and ], approximately between 1700 and 1200 BC.<ref name="Howard 2016-4"/> As the Hittite kingdom was disintegrating, further waves of Indo-European peoples migrated from southeastern Europe, which was followed by warfare.<ref>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|pp=26–27}}</ref> The ] were also present in modern-day ].<ref>{{harvnb|Ahmed|2006|p=1576}}</ref> It is not known if the ] is based on historical events.<ref>{{harvnb|Jablonka|2012|pp=724–726}}</ref> ] layers matches most with '']''{{'}}s story.<ref>{{harvnb|McMahon|2012|p=17}}</ref> | |||

| The earliest recorded inhabitants of Anatolia were the ] and ], non-Indo-European peoples who inhabited central and eastern Anatolia, respectively, as early as c. 2300 BC. Indo-European ] came to Anatolia and gradually absorbed the Hattians and Hurrians c. 2000–1700 BC. The first major empire in the area was founded by the Hittites, from the 18th through the 13th century BC. The ]ns conquered and settled parts of southeastern Turkey as early as 1950 BC until the year 612 BC,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www3.uakron.edu/ziyaret/timeline_3period.html|title=Ziyaret Tepe – Turkey Archaeological Dig Site|publisher=uakron.edu|access-date=4 September 2010}}</ref> although they ] in the region, namely in ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aina.org/articles/assyrianidentity.pdf|title=Assyrian Identity in Ancient Times And Today'|access-date=4 September 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ===Early classical antiquity=== | |||

| ] re-emerged in Assyrian inscriptions in the 9th century BC as a powerful northern rival of Assyria.<ref>{{cite book|title=Urartian Material Culture As State Assemblage: An Anomaly in the Archaeology of Empire|first=Paul|last=Zimansky|page=103}}</ref> Following the collapse of the Hittite empire c. 1180 BC, the ]ns, an Indo-European people, achieved ascendancy in Anatolia until their kingdom was destroyed by the ] in the 7th century BC.<ref name="TroyHittiteEmpirePhrygians">{{cite web|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/03/waa/ht03waa.htm|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20060910042040/http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/03/waa/ht03waa.htm|archivedate=10 September 2006|title=Anatolia and the Caucasus, 2000–1000 B.C. in ''Timeline of Art History.''|author=The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York|authorlink=Metropolitan Museum of Art|publisher=New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art|access-date=21 December 2006|date=October 2000}}</ref> Starting from 714 BC, Urartu shared the same fate and dissolved in 590 BC,<ref>{{cite book|first=Georges|last=Roux|title=Ancient Iraq|page=314}}</ref> when it was conquered by the ]. The most powerful of Phrygia's successor states were ], ] and ]. | |||

| {{Main|Classical Anatolia}} | |||

| {{See also|Phrygia|Lydia|Lycia|Caria|Urartu|Achaemenid Empire|Hellenistic period}} | |||

| ] is a {{convert|470|mi|km|order=flip|sp=us}} long hiking path in Southwestern Turkey.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/photo-story-turkey-lycian-way |title=Photo story: tombs, turquoise seas and trekking along Turkey's Lycian Way |last=Denisyuk |first=Yulia |date=29 October 2023 |website=National Geographic |publisher=National Geographic Traveller}}</ref>]] | |||

| Around 750 BC, ] had been established, with its two centers in ] and modern-day ].<ref name="Howard 2016-2">{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=27}}</ref> ] spoke an Indo-European language, which was closer to ] than Anatolian languages.<ref name="McMahon_Steadman_2012_p_522"/> Phrygians shared Anatolia with ] and ]. Luwian-speakers were probably the majority in various Anatolian Neo-Hittite states.<ref>{{harvnb|Yakubovich|2012|p=538}}</ref> Urartians spoke a non-Indo-European language and their capital was around ].<ref>{{harvnb|Zimansky|2012|p=552}}</ref><ref name="Howard 2016-2"/> Urartu and Phrygia fell in seventh century BC.<ref name="Howard 2016-2"/><ref name="Howard 2016">{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=28}}</ref> They were replaced by ], ] and ].<ref name="Howard 2016"/> These three cultures "can be considered a reassertion of the ancient, indigenous culture of the Hattian cities of Anatolia".<ref name="Howard 2016"/> | |||

| ===Antiquity=== | |||

| {{Main|Classical Anatolia|Hellenistic period}} | |||

| ] (modern ]) was built in the 4th century BC by ], the ] ] (governor) of ]. The ] (Tomb of Mausolus) was one of the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-asia/mausoleum-halicarnassus-wonder-ancient-world-003088|title=The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus: A Wonder of the Ancient World|publisher=ancient-origins.net|date=19 May 2015}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] in ] was built by the ] in 114–117.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ancient.eu/Celsus_Library/|title=Celsus Library|publisher=Ancient.eu|author=Mark Cartwright|access-date=2 February 2017}}</ref> The ] in Ephesus, built by king ] of ] in the 6th century BC, was one of the ].<ref>{{cite web|title=The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus: The Un-Greek Temple and Wonder|url=http://www.ancient.eu/article/128/|website=ancient.eu|access-date=17 February 2017}}</ref>]] | |||

| Before 1200 BC, there were four Greek-speaking settlements in Anatolia, including ].<ref name="Britannica">{{Cite web|title=Anatolia – Greek colonies on the Anatolian coasts, c. 1180–547 bce|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Anatolia/Greek-colonies-on-the-Anatolian-coasts-c-1180-547-bce|access-date=2 February 2024|website=]|language=en|quote=Before the Greek migrations that followed the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200 BCE), probably the only Greek-speaking communities on the west coast of Anatolia were Mycenaean settlements at Iasus and Müskebi on the Halicarnassus peninsula and walled Mycenaean colonies at Miletus and Colophon. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230321122314/https://www.britannica.com/place/Anatolia/Greek-colonies-on-the-Anatolian-coasts-c-1180-547-bce |archive-date=21 March 2023 |url-status=live }}</ref> Around 1000 BC, ] to the west coast of Anatolia. These eastern Greek settlements played a vital role in shaping the Archaic Greek civilization;<ref name="Howard 2016-2"/><ref>{{harvnb|Harl|2012|p=760}}: "Greek cities on the shores of Asia Minor and on the Aegean islands were the nexus | |||

| Starting around 1200 BC, the coast of Anatolia was heavily settled by ] and ] ]. Numerous important cities were founded by these colonists, such as ], ], ] (now ]) and ] (now ]), the latter founded by ] colonists from ] in 657 BC.{{Citation needed|date=March 2020}} The first state that was called ] by neighbouring peoples was the state of the ] ], which included parts of eastern Turkey beginning in the 6th century BC. In Northwest Turkey, the most significant tribal group in Thrace was the ], founded by ].<ref name="LewisBoardman1994">{{cite book|author1=D.M. Lewis|author2=John Boardman|title=The Cambridge Ancient History|url={{Google books |plainurl=yes |id=vx251bK988gC |page=462 }} |access-date=7 April 2013|year=1994|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-23348-4|page=444}}</ref> | |||

| of trade and cultural exchange in the early Greek world, so Archaic Greek civilization was to a great extent the product of the Greek cities of Asia Minor."</ref> important ] included ], ], ], ] (now ]) and ] (now ]), the latter founded by colonists from ] in the seventh century BCE.<ref>{{harvnb|Harl|2012|pp=753-756}}</ref> These settlements were grouped as ], ], and ], after the specific Greek groups that settled them.<ref>{{harvnb|Greaves|2012|p=505}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Harl|2012|p=753}}</ref> Further Greek colonization in Anatolia was led by Miletus and ] in 750–480 BC.<ref>{{harvnb|Harl|2012|pp=753–754}}</ref> The Greek cities along the Aegean prospered with trade, and saw remarkable scientific and scholarly accomplishments.<ref name="y319">{{cite book | last=Rovelli | first=C. | title=Anaximander: And the Birth of Science | publisher=Penguin Publishing Group | year=2023 | isbn=978-0-593-54237-8 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=huNxEAAAQBAJ | access-date=2024-06-01 | pages=20–30}}</ref> ] and ] from Miletus founded the ], thereby laying the foundations of ] and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Baird|2016|p=8}}</ref> | |||

| ] in ] was built by the ] in 114–117.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Celsus_Library/|title=Celsus Library|publisher=]|author=Mark Cartwright|access-date=2 February 2017|archive-date=28 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240328151448/https://www.worldhistory.org/Library_of_Celsus/?arg1=Celsus_Library&arg2=&arg3=&arg4=&arg5=|url-status=live}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] attacked eastern Anatolia in 547 BC, and ] eventually ].<ref name="Howard 2016"/> In the east, the ] was part of the Achaemenid Empire.<ref name="Howard 2016-2"/> Following the ], the Greek city-states of the Anatolian Aegean coast regained independence, but most of the interior stayed part of the Achaemenid Empire.<ref name="Howard 2016"/> Two of the ], the ] in Ephesus, and the ], were located in Anatolia.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus: The Un-Greek Temple and Wonder|url=https://www.worldhistory.org/article/128/|website=]|access-date=17 February 2017|archive-date=28 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240328151417/https://www.worldhistory.org/Temple_of_Artemis_at_Ephesus/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| All of modern-day Turkey was conquered by the Persian ] during the 6th century BC.<ref name="A companion to Ancient Macedonia">Joseph Roisman, Ian Worthington. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. {{ISBN|1-4443-5163-X}} pp. 135–138, 343</ref> The ] started when the Greek city states on the coast of Anatolia rebelled against Persian rule in 499 BC. The territory of Turkey later fell to ] in 334 BC,<ref name="PersiansInAsiaMinor">{{cite web|url=http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/GREECE/PERSIAN.HTM |url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5uNLYWJA2?url=http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/GREECE/PERSIAN.HTM |archivedate=20 November 2010 |title=Ancient Greece: The Persian Wars |author=Hooker, Richard |publisher=Washington State University, Washington, United States |access-date=22 December 2006 |date=6 June 1999}}</ref> which led to increasing cultural homogeneity and ] in the area.<ref name="SteadmanMcMahon20112"/> | |||

| Following the victories of Alexander in ] and ], the Achaemenid Empire collapsed and Anatolia became part of the ].<ref name="Howard 2016"/> This led to increasing cultural homogeneity and ] of the Anatolian interior,<ref>{{harvnb|McMahon|Steadman|2012a|p=5}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|McMahon|2012|p=16}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Sams|2012|p=617}}</ref> which met resistance in some places.<ref name=Howard_2016_a>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=29}}: "The sudden disappearance of the Persian Empire and the conquest of virtually the entire Middle Eastern world from the Nile to the Indus by Alexander the Great caused tremendous political and cultural upheaval." ... "statesmen throughout the conquered regions attempted to implement a policy of Hellenization. For indigenous elites, this amounted to the forced assimilation of native religion and culture to Greek models. It met resistance in Anatolia as elsewhere, especially from priests and others who controlled temple wealth."</ref> Following Alexander's death, the ] ruled large parts of Anatolia, while native Anatolian states emerged in the Marmara and Black Sea areas. In eastern Anatolia, ] appeared. In third century BC, ] invaded central Anatolia and continued as a major ethnic group in the area for around 200 years. They were known as the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Mitchell|1995|pp=3–4}}</ref> | |||

| Following Alexander's death in 323 BC, Anatolia was subsequently divided into a number of small Hellenistic kingdoms, all of which became part of the ] by the mid-1st century BC.<ref name="AlexanderToRome">{{cite web|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/04/waa/ht04waa.htm|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061214003932/http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/04/waa/ht04waa.htm|archivedate=14 December 2006|title=Anatolia and the Caucasus (Asia Minor), 1000 B.C. – 1 A.D. in ''Timeline of Art History.''|author=The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York|authorlink=Metropolitan Museum of Art|publisher=New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art|access-date=21 December 2006|date=October 2000}}</ref> The process of Hellenization that began with Alexander's conquest accelerated under Roman rule, and by the early centuries of the ], the local Anatolian languages and cultures had become extinct, being largely replaced by ] and culture.<ref name="FreedmanMyers20002"/><ref name="Hout2011">{{cite book|author=Theo van den Hout|title=The Elements of Hittite|url={{Google books |plainurl=yes |id=QDJNg5Nyef0C |page=1 }} |access-date=24 March 2013|year= 2011|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-139-50178-1|page=1}}</ref> From the 1st century BC up to the 3rd century CE, large parts of modern-day Turkey were contested between the ] and neighbouring ] through the frequent ]. | |||

| === |

===Rome and Byzantine Empire=== | ||

| {{Main| |

{{Main|Classical Anatolia|Byzantine Anatolia}} | ||

| {{See also| |

{{See also|Roman Republic|Roman Empire|Christianity in Turkey|Byzantine Empire}} | ||

| ] in ] was built by the ] emperor ] in 532–537 AD.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://global.britannica.com/topic/Hagia-Sophia|title=Hagia Sophia|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=2 February 2017}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] in 555 under ], at its greatest extent]] | |||

| According to ] 11,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://biblehub.com/acts/11-26.htm|title=Acts 11:26 and when he found him, he brought him back to Antioch. So for a full year they met together with the church and taught large numbers of people. The disciples were first called Christians at Antioch.|website=biblehub.com}}</ref> ] (now ]), a city in southern Turkey, is the birthplace of the ].<ref>'']'', Vol. I, p. 186 (p. 125 of 612 in ).</ref> | |||

| When ] requested assistance in its conflict with the Seleucids, ] intervened in Anatolia in the second century BC. Without an heir, Pergamum's king left the kingdom to Rome, which was annexed as ]. Roman influence grew in Anatolia afterwards.<ref>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=29}}</ref> Following ] massacre, and ] with ], Rome emerged victorious. Around the 1st century BC, ], while turning rest of Anatolian states into Roman satellites.<ref>{{harvnb|Hoyos|2019|pp=35–37}}</ref> Several ], with peace and wars alternating.<ref>{{harvnb|Hoyos|2019|pp=62, 83, 115}}</ref> | |||

| In 324, ] chose Byzantium to be the new capital of the Roman Empire, renaming it ]. Following the death of ] in 395 and the permanent division of the Roman Empire between his two sons, the city, which would popularly come to be known as ], became the capital of the ]. This empire, which would later be branded by historians as the ], ruled most of the territory of present-day Turkey until the ];<ref>{{cite web|url=http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/cities/turkey/istanbul/istanbul.html|title=Constantinople/Istanbul|author=Daniel C. Waugh|publisher=University of Washington, Seattle, Washington|access-date=26 December 2006|year=2004}}</ref> although the eastern regions remained firmly in ] hands up to the first half of the seventh century. The frequent ], as part of the centuries long-lasting ], fought between the neighbouring rivalling Byzantines and Sasanians, took place in various parts of present-day Turkey and decided much of the latter's{{Clarify|reason=not clear what "the latter" is referring to|date=March 2020}} history from the fourth century up to the first half of the seventh century. | |||

| According to ], early Christian Church had significant growth in Anatolia because of ] efforts. Letters from St. Paul in Anatolia comprise the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=30}}</ref> Under Roman authority, ] such as ] in 325 served as a guide for developing "orthodox expressions of basic Christian teachings".<ref>{{harvnb|Howard|2016|p=30}}</ref> | |||

| Several ] of the ] were held in cities located in present-day Turkey including the ] (]) in 325, the ] (Istanbul) in 381, the ] in 431, and the ] (]) in 451.<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = Cambridge University Press| isbn = 978-1-107-02175-4| last = Maas| first = Michael| title = The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila| date = 2015 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=67dUBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA331}}</ref> | |||

| ] in ] (now ]) was built by the ] emperor ] in 532–537.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://global.britannica.com/topic/Hagia-Sophia|title=Hagia Sophia|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=2 February 2017|archive-date=29 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210429163151/https://global.britannica.com/topic/Hagia-Sophia|url-status=live}}</ref>]] | |||

| ===Seljuks and the Ottoman Empire=== | |||

| The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the ] centered in ] during ] and the ]. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the ] in the 5th century AD, and continued to exist until the ] to the ] in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the ]. The term ''Byzantine Empire'' was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as ''Romans''. Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to ], the ], and the predominance of ] instead of ], modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier ''Roman Empire'' and the later ''Byzantine Empire''.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| {{Main|Seljuk dynasty|Ottoman dynasty}} | |||

| {{see also|Turkic migration|Mongol invasions of Anatolia|Seljuk Empire|Sultanate of Rum|Ottoman Empire}} | |||

| In the early Byzantine Empire period, the Anatolian coastal areas were Greek speaking. In addition to natives, interior Anatolia had diverse groups such as ], ], ] and ]. Interior Anatolia had been "heavily Hellenized".<ref name=Horrocks_pp_778-779>{{harvnb|Horrocks|2008|pp=778–779}}: "Thus the majority of traditional 'Greek' lands, including the coastal areas of Asia Minor, remained essentially Greek-speaking, despite the superimposition of Latin and the later Slavic incursions into the Balkans during the sixth and seventh centuries. Even on the Anatolian plateau, where Hellenic culture had come only with Alexander's conquests, both the extremely heterogeneous indigenous populations and immigrant groups (including Celts, Goths, Jews, and Persians) had become heavily Hellenized, as the steady decline in epigraphic evidence for the native languages and the great mass of public and private inscriptions in Greek demonstrate. Though the disappearance of these languages from the written record did not entail their immediate abandonment as spoken languages,..."</ref> ] eventually became extinct after ] of Anatolia.<ref>{{harvnb|van den Hout|2011|p=1}}</ref> | |||

| The ] originated from the '']'' branch of the ] who resided on the periphery of the ], in the ] of the Oğuz confederacy, to the north of the ] and ]s, in the 9th century.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Al Hind: The Making of the Indo Islamic World, Vol. 1, Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries|first=Andre|last=Wink|publisher=Brill Academic Publishers|year=1990|isbn=978-90-04-09249-5|page=21}}</ref> In the 10th century, the Seljuks started migrating from their ancestral homeland into ], which became the administrative core of the ], after its foundation by ].<ref name=peter.mackenzie.org>{{cite web|title=The Seljuk Turks|url=http://peter.mackenzie.org/history/hist2021.htm|website=peter.mackenzie.org|access-date=9 August 2014}}</ref> | |||

| ===Seljuks and Anatolian beyliks=== | |||

| In the latter half of the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks began penetrating into ] and the eastern regions of Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuks defeated the Byzantines at the ], starting the ] process in the area; the Turkish language and ] were introduced to Armenia and Anatolia, gradually spreading throughout the region. The slow transition from a predominantly ] and ]-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly ] and Turkish-speaking one was underway. The ] of ], which was established in ] during the 13th century by ] poet ], played a significant role in the ] of the diverse people of Anatolia who had previously been ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Davison|first1=Roderic H.|title=Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774–1923: The Impact of the West|date=2013|publisher=University of Texas Press|isbn=978-0-292-75894-0|pages=3–5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NQvUAAAAQBAJ}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Katherine Swynford Lambton|editor1-first=Ann|editor2-last=Lewis|editor2-first=Bernard|title=The Cambridge history of Islam|date=1977|publisher=Cambridge Univ. Press|location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-29135-4|page=233|edition=Reprint.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4AuJvd2Tyt8C}}</ref> Thus, alongside the Turkification of the territory, the ] Seljuks set the basis for a ] in Anatolia,<ref>Craig S. Davis. {{ISBN|0-7645-5483-2}} p. 66</ref> which their eventual successors, ], would take over.<ref>Thomas Spencer Baynes. . Werner, 1902</ref><ref>Emine Fetvacı. | |||

| {{main|Seljuk Empire|Sultanate of Rum|Anatolian beyliks}} | |||

| p 18</ref> | |||

| {{further|Turkic migration|Oghuz Turks|Turkification}} | |||

| {{Location map+ | |||

| {{Multiple image|align=left|direction=vertical|image1=Topkapı - 01.jpg|image2=Dolmabahçe Palace (cropped).JPG|caption2=] and ] palaces were the primary residences of the ] ] and the administrative centre of the empire between 1465 to 1856<ref name="nytimes">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/22/travel/center-of-ottoman-power.html|title=Center of Ottoman Power|work=New York Times|last= Simons|first=Marlise |access-date=4 June 2009 | date=22 August 1993}}</ref> and 1856 to 1922,<ref name=dolmabahcepalace>{{cite web|title=Dolmabahce Palace|url=http://www.dolmabahcepalace.com/listingview.php?listingID=3|website=dolmabahcepalace.com|access-date=4 August 2014}}</ref> respectively.}} | |||

| | Seljuk Empire | |||

| | width=300 <!-- DO NOT CHANGE MAP SIZE (300) AS THIS WILL DISPLACE THE LABELS --> | |||

| | float = right | |||

| | nodiv= 1 | mini= 1 | relief= yes | |||

| | places = | |||

| {{Annotation|270|05|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=10|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|210|90|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|150|15|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|30|20|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|25|105|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|97|120|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|95|51|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|1|40|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|50|60|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|245|145|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|186|45|]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=6.5|color=#000000}} | |||

| {{Annotation|272|155|] ]|text-align=center|font-weight=bold|font-style=normal|font-size=12|color=#000000}} | |||

| | caption=] circa 1090, during the reign of ]. To the west, Anatolia was under the independent rule of ] as the ]. | |||

| }} | |||