| Revision as of 05:06, 12 September 2010 view source216.229.233.14 (talk) →Discovery← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:46, 31 December 2024 view source Stephan Leeds (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions31,419 edits →Orcus: “second” is not so complex as to justify resorting to notation in figures | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Dwarf planet}} | ||

| {{About|the dwarf planet|the deity|Pluto (mythology)|other uses|Pluto (disambiguation)}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| Please note the formatting and layout of this infobox has been matched with the other bodies of the Solar System. Please do not arbitrarily change it without discussion. | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

| Scroll down to edit the contents of this page. | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| Additional parameters for this template are available at ]. | |||

| {{Use American English|date=August 2024}} | |||

| --> | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=August 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox Planet | |||

| {{Infobox planet | |||

| | bgcolour=#A0FFA0 | |||

| | name = Pluto | | name = 134340 Pluto | ||

| | minorplanet = yes | |||

| | symbol = ] | |||

| | symbol = ] or ]<!--Do not delete the bident symbol; it is not merely astrological. NASA has used it; moreover, the IAU specifically discourages use of symbols--> | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| | image = Pluto in True Color - High-Res.jpg | |||

| | caption = Computer-generated map of Pluto from ] images, synthesised true colour<ref group=note>The HST observations were made in two wavelengths, which is insufficient to directly make a true colour image. However, the surface maps at each wavelength do limit the shape of the ] that could be produced by the materials that are potentially on Pluto's surface. These spectra, generated for each resolved point on the surface, are then converted to the ] colour values seen here. See Buie et al, 2010.</ref> and among the highest resolutions possible with current technology | |||

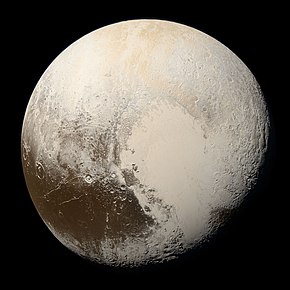

| | caption = Pluto, imaged by the '']'' spacecraft, July 2015.{{efn|name = caption|This photograph was taken by the ] telescope aboard '']'' on July 14, 2015, from a distance of {{convert|35,445|km|mi|abbr=on}}}} The most prominent feature in the image, the bright, youthful plains of ] and ], can be seen at right. It contrasts the darker, cratered terrain of ] at lower left. | |||

| | discovery = yes | |||

| | background = PapayaWhip | |||

| | discoverer = ] | |||

| | discoverer = ] | |||

| | discovered = February 18, 1930 | | discovered = February 18, 1930 | ||

| | discovery_site = ] | |||

| | mp_name = '''134340 Pluto''' | |||

| | mpc_name = (134340) Pluto | |||

| | named_after = ] | | named_after = ] | ||

| | mp_category = {{Plain list| | |||

| | mp_category = ],<br />],<br />],<br />],<br />] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] object | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | orbit_ref = <ref name="TOP2013" />{{efn|name = MeanElements|The mean elements here are from the Theory of the Outer Planets (TOP2013) solution by the Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides (IMCCE). They refer to the standard equinox J2000, the barycenter of the Solar System, and the epoch J2000.}} | |||

| | epoch = ] | | epoch = ] | ||

| | earliest_precovery_date = August 20, 1909 | |||

| | aphelion = 7,375,927,931 km<br />49.305 032 87 ] | |||

| | aphelion = {{Plain list| | |||

| | perihelion = 4,436,824,613 km<br />29.658 340 67 AU | |||

| * {{val|49.305|ul=AU}} | |||

| | semimajor = 5,906,376,272 km<br />39.481 686 77 AU | |||

| * ({{nowrap|{{val|fmt=commas|7.37593|u=billion km}}}}) | |||

| | eccentricity = 0.248 807 66 | |||

| * February 2114 | |||

| | inclination = 17.141 75°<br />11.88° to Sun's equator | |||

| }} | |||

| | asc_node = 110.303 47° | |||

| | perihelion = {{Plain list| | |||

| | arg_peri = 113.763 29° | |||

| * {{val|29.658|u=AU}} | |||

| | period = 90,613.305 days<br />248.09 ]<br />14,164.4 Pluto ]s<ref name="planet_years">{{cite web|url = http://cseligman.com/text/sky/rotationvsday.htm|title = Rotation Period and Day Length|last = Seligman |first = Courtney|accessdate = 2009-08-13}}</ref> | |||

| * ({{nowrap|{{val|fmt=commas|4.43682|u=billion km}}}})<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | synodic_period = 366.73 days | |||

| * (September 5, 1989)<ref name="jpl-ssd-horizons" /> | |||

| | avg_speed = 4.666 km/s | |||

| }} | |||

| | satellites = ] | |||

| | semimajor = {{Plain list| | |||

| | physical_characteristics = yes | |||

| * {{val|39.482|u=AU}} | |||

| | mean_radius = {{nowrap|1,153 ± 10 km}}<ref name="Buie06"/><br />0.18 Earths | |||

| * ({{nowrap|{{val|fmt=commas|5.90638|u=billion km}}}}) | |||

| | surface_area = 1.665{{e|7}} km²<ref group=note>Surface area derived from the radius ''r'': <math>4\pi r^2</math>'''.</ref><br />0.033 Earths | |||

| }} | |||

| | volume = 6,39{{e|9}} km³<ref group=note>Volume ''v'' derived from the radius ''r'': <math>4\pi r^3/3</math>'''.</ref><br />0.0059 Earths | |||

| | eccentricity = {{val|0.2488}} | |||

| | mass = (1.305 ± 0.007){{e|22}} kg<ref name="Buie06"/><br />0.002 1 Earths<br />0.178 moon | |||

| | inclination = {{Plain list| | |||

| | density = 2.03 ± 0.06 g/cm³<ref name="Buie06"/> | |||

| * {{val|17.16|u=°}} | |||

| | surface_grav = {{Gr|13.05|1153}} ]<ref group=note>Surface gravity derived from the mass ''m'', the ] ''G'' and the radius ''r'': <math>Gm/r^2</math>.</ref><br />0.067 ] | |||

| * (11.88° to Sun's equator) | |||

| | escape_velocity = {{V2|13.05|1153}} km/s<ref group=note>Escape velocity derived from the mass ''m'', the ] ''G'' and the radius ''r'': {{math|{{radical|2Gm/r}}}}.</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | sidereal_day = ]<br />6 d 9 h 17 m 36 s | |||

| | asc_node = {{val|110.299|u=°}} | |||

| | rot_velocity = 47.18 km/h | |||

| | arg_peri = {{val|113.834|u=°}} | |||

| | axial_tilt = 119.591 ± 0.014° (to orbit)<ref name="Buie06">{{cite journal | |||

| | period = {{Plain list| | |||

| | author = M. W. Buie, W. M. Grundy, E. F. Young, L. A. Young, S. A. Stern | |||

| * {{val|247.94}} ]<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | title = Orbits and photometry of Pluto's satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005 P2 | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{val|fmt=commas|90560|u=days}}}}<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | journal = Astronomical Journal | |||

| <!-- * {{nowrap|{{val|fmt=commas|14164.4}}}} Plutonian ]s<ref name="planet_years" /> --> | |||

| | year=2006 | |||

| }} | |||

| | volume=132 | |||

| | synodic_period = 366.73 days<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | pages=290 | |||

| | avg_speed = 4.743 km/s<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-bib_query?bibcode=2006AJ....132..290B&db_key=AST&data_type=HTML&format=&high=444b66a47d27727 | |||

| | mean_anomaly = {{val|14.53|u=]}} | |||

| |id = {{arxiv|archive=astro-ph|id=0512491}} | doi = 10.1086/504422 | |||

| | satellites = ] | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=inclination group=note>Based on the orientation of Charon's orbit, which is assumed the same as Pluto's spin axis due to the mutual ].</ref> | |||

| | mean_radius = {{Plain list| | |||

| | right_asc_north_pole = 133.046 ± 0.014°<ref name="Buie06"/> | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{val|fmt=commas|1188.3|0.8|u=km}}}}<ref name = "Pluto System after New Horizons">{{cite journal |last1=Stern |first1=S.A. |last2=Grundy |first2=W. |last3=McKinnon |first3=W.B. |last4=Weaver |first4=H.A. |last5=Young |first5=L.A. |title=The Pluto System After New Horizons |journal=Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics |volume=2018 |pages=357–392 |arxiv=1712.05669 |year=2017 |bibcode=2018ARA&A..56..357S |s2cid=119072504 |doi=10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-051935|issn = 0066-4146}}</ref><ref name="Nimmo2017">{{cite journal |last=Nimmo |first=Francis |display-authors=etal |title=Mean radius and shape of Pluto and Charon from New Horizons images |journal=Icarus |date=2017 |volume=287 |pages=12–29 |bibcode=2017Icar..287...12N |arxiv=1603.00821 |s2cid=44935431 |doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2016.06.027}}</ref> | |||

| | declination = −6.145 ± 0.014°<ref name="Buie06"/> | |||

| * 0.1868 ]}} | |||

| | albedo = 0.49–0.66 (varies by 35%)<ref name=Hamilton>{{cite web | |||

| | dimensions = {{val|fmt=commas|2376.6|1.6|u=km}} (observations consistent with a sphere, predicted deviations too small to be observed)<ref name="Nimmo2017"/> | |||

| |date=2006-02-12 | |||

| | surface_area = {{Plain list| | |||

| |title=Dwarf Planet Pluto | |||

| * {{val|1.774443|e=7|u=km2}}{{efn|name=Surface area}} | |||

| |publisher=Views of the Solar System | |||

| * 0.035 Earths | |||

| |author=Calvin J. Hamilton | |||

| }} | |||

| |url=http://www.solarviews.com/eng/pluto.htm | |||

| | volume = {{Plain list| | |||

| |accessdate=2007-01-10}}</ref><ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet"/> | |||

| * {{val|7.057|0.004|e=9|u=km3}}{{efn|name=Volume}} | |||

| | magnitude = 13.65<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet"/> to 16.3<ref name=AstDys-Pluto>{{cite web | |||

| * {{val|0.00651|u=Earths}} | |||

| |title=AstDys (134340) Pluto Ephemerides | |||

| }} | |||

| |publisher=Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy | |||

| | mass = {{Plain list| | |||

| |url=http://hamilton.dm.unipi.it/astdys/index.php?pc=1.1.3.1&n=134340&oc=500&y0=1870&m0=2&d0=9&h0=0&mi0=0&y1=1870&m1=3&d1=20&h1=0&mi1=0&ti=1.0&tiu=days | |||

| * {{val|1.3025|0.0006|e = 22|u=kg}}<ref name="Brozovic2024"/><!-- Calculated from GM=869.3 ± 0.4 km3 s–2 --> | |||

| |accessdate=2010-06-27}}</ref><br/>(mean is 15.1)<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet"/> | |||

| * {{val|0.00218|u=]|fmt=none}} | |||

| | abs_magnitude = −0.7<ref name=jpldata>{{cite web | |||

| * 0.177 ] | |||

| |title=JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 134340 Pluto | |||

| }} | |||

| |url=http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=Pluto | |||

| | density = {{val|1.853|0.004|u=g/cm3}}<ref name="Brozovic2024"/> | |||

| |accessdate=2008-06-12}}</ref> | |||

| | surface_grav = {{cvt|0.620|m/s2|g0|lk=out}}{{efn|name = Surface gravity}} | |||

| | angular_size = 0.065" to 0.115"<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet"/><ref group=note>Based on geometry of minimum and maximum distance from Earth and Pluto radius in the factsheet</ref> | |||

| | escape_velocity = {{val|1.212}} km/s{{efn|name = Escape velocity}} | |||

| | pronounce = {{IPAc-en|en-us-Pluto.ogg|ˈ|p|l|uː|t|oʊ}},<ref group=note>In US dictionary transcription, {{USdict|plōō′·tō}}. From the {{lang-la|Plūto}}</ref> | |||

| | rotation = {{Plain list| | |||

| | adjectives = Plutonian | |||

| * {{val|−6.38680|u=day}} | |||

| * −6 d, 9 h, 17 m, 00 s | |||

| }}<ref name="planet_years">{{cite web |url=http://cseligman.com/text/sky/rotationvsday.htm |title=Rotation Period and Day Length |last=Seligman |first=Courtney |access-date=June 12, 2021 |archive-date=September 29, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180929010908/http://cseligman.com/text/sky/rotationvsday.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | sidereal_day = {{Plain list| | |||

| * {{val|−6.387230|u=day}} | |||

| * −6 d, 9 h, 17 m, 36 s | |||

| }} | |||

| | rot_velocity = {{cvt|47.18|km/h|m/s|disp=out}}{{citation needed|date=July 2024}} | |||

| | axial_tilt = {{val|122.53|u=°}} (to orbit)<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | right_asc_north_pole = 132.993°<ref name="Archinal" /> | |||

| | declination = −6.163°<ref name="Archinal" /> | |||

| | albedo = 0.52 ]<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /><br />0.72 ]<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | magnitude = 13.65<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> to 16.3<ref name="AstDys-Pluto" /> <br /> (mean is 15.1)<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> | |||

| | abs_magnitude = −0.44<ref name="jpldata" /> | |||

| | angular_size = 0.06{{pprime}} to 0.11{{pprime}}<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" />{{efn|name = Angular size}} | |||

| | pronounced = {{IPAc-en|audio=en-us-Pluto.ogg|ˈ|p|l|uː|t|oʊ}} | |||

| | adjectives = ] {{IPAc-en|p|l|uː|ˈ|t|oʊ|n|i|ə|n}}<ref>{{OED|Plutonian}}</ref> | |||

| | atmosphere = yes | | atmosphere = yes | ||

| | temperatures = yes | |||

| | temp_name1 = ] | | temp_name1 = ] | ||

| | min_temp_1 = 33 K | | min_temp_1 = 33 K | ||

| | mean_temp_1 = 44 K | | mean_temp_1 = 44 K (−229 °C) | ||

| | max_temp_1 = 55 K | | max_temp_1 = 55 K | ||

| | surface_pressure = 1.0 ] (2015)<ref name=Stern2015 /><ref>{{cite news |last=Amos |first=Jonathan |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-33657447 |title=New Horizons: Pluto may have 'nitrogen glaciers' |publisher=BBC News |date=July 23, 2015 |access-date=July 26, 2015 |quote=It could tell from the passage of sunlight and radiowaves through the Plutonian "air" that the pressure was only about 10 microbars at the surface |archive-date=October 27, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171027182142/http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-33657447 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | surface_pressure = 0.30 ] (summer maximum) | |||

| | atmosphere_composition = ], ] | | atmosphere_composition = ], ], ]<ref name="Physorg April 19, 2011" /> | ||

| | note=no | | note = no | ||

| | scale_height = | |||

| | flattening = <1%<ref name="Stern2015" /> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- Per ], there is no need to cite material in the lead if it is cited elsewhere. | |||

| '''Pluto''', ] '''134340 Pluto''', is the second-largest known ] in the ] (after ]) and the tenth-largest body observed directly orbiting the ]. Originally classified as a planet, Pluto is now considered the largest member of a distinct population known as the ].<ref name=wiki-kbo group=note >Although Eris is larger than Pluto, it resides in the ]. Misplaced Pages convention treats this as a distinct region from the Kuiper belt, so Pluto becomes the largest Kuiper belt object.</ref> | |||

| --> | |||

| '''Pluto''' (]: '''134340 Pluto''') is a ] in the ], a ring of ]. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-]ive known object to directly orbit the ]. It is the largest known ] by volume, by a small margin, but is less massive than ]. Like other Kuiper belt objects, Pluto is made primarily of ice and rock and is much smaller than the ]s. Pluto has roughly one-sixth the mass of the ], and one-third its volume. | |||

| Like other members of the Kuiper belt, Pluto is composed primarily of rock and ice and is relatively small: approximately a fifth the mass of the ]'s ] and a third its volume. It has an ] and highly inclined orbit that takes it from 30 to 49 ] (4.4–7.4 billion km) from the Sun. This causes Pluto to periodically come closer to the Sun than ]. | |||

| Pluto has a moderately ] and ] orbit, ranging from {{convert|30|to|49|AU|e9km e9mi|lk=on|abbr=off}} from the Sun. Light from the Sun takes 5.5 hours to reach Pluto at its orbital distance of {{convert|39.5|AU|e9km e9mi|abbr=unit|}}. Pluto's eccentric orbit periodically brings it closer to the Sun than ], but a stable ] prevents them from colliding. | |||

| From its discovery in 1930 until 2006, Pluto was considered the Solar System's ]. In the late 1970s, following the discovery of minor planet ] in the outer Solar System and the recognition of Pluto's very low mass, its status as a major planet began to be questioned.<ref name=ridpath>{{cite journal|author=Ian Ridpath|title=Pluto—Planet or Imposter?|url=http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/ianridpath/Pluto.pdf|journal=Astronomy|date=December 1978 |pages=6–11}}</ref> | |||

| In the late 20th and early 21st century, many objects similar to Pluto were discovered in the outer Solar System, notably the ] ] in 2005, which is 27% more massive than Pluto.<ref>{{cite web|title=Astronomers Measure Mass of Largest Dwarf Planet|work=hubblesite|year=2007|url=http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2007/24/full/|accessdate=2007-11-03}}</ref> On August 24, 2006, the ] (IAU) ]. This definition excluded Pluto as a planet and added it as a member of the new category "dwarf planet" along with Eris and ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/4737647.stm | |||

| | title = Farewell Pluto? | |||

| | author = A. Akwagyiram | |||

| | publisher = BBC News | |||

| | date = 2005-08-02 | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-03-05 | |||

| }}</ref> After the reclassification, Pluto was added to the list of ]s and given the ] 134340.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url=http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/mpec/K06/K06R19.html | |||

| | title = MPEC 2006-R19 : Editorial Notice | |||

| | author = T. B. Spahr | |||

| | publisher = Minor Planet Center | |||

| | date = 2006-09-07 | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-09-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.newscientistspace.com/article/dn10028-pluto-added-to-official-minor-planet-list.html | |||

| | title = Pluto added to official "minor planet" list | |||

| | author = D. Shiga | publisher=] | |||

| | date = 2006-09-07 | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-09-08}}</ref> A number of scientists continue to hold that Pluto should be classified as a planet.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/main.jhtml?xml=/earth/2008/08/10/scipluto110.xml | |||

| | title = Pluto should get back planet status, say astronomers | |||

| | author = Richard Gray | |||

| | publisher = The Telegraph | |||

| | date = 2008-08-10 | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-08-09 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Pluto has ]: ], the largest, whose diameter is just over half that of Pluto; ]; ]; ]; and ]. Pluto and Charon are sometimes considered a ] because the ] of their orbits does not lie within either body, and they are ]. '']'' was the first spacecraft to visit Pluto and its moons, making a ] on July 14, 2015, and taking detailed measurements and observations. | |||

| Pluto and its largest moon, ], are sometimes treated together as a ] because the ] of their orbits does not lie within either body.<ref> | |||

| Pluto was discovered in 1930 by ], making it by far the first known object in the Kuiper belt. It was immediately hailed as the ]. However,<ref name=T&M/>{{rp|27}} its planetary status was questioned when it was found to be much smaller than expected. These doubts increased following the discovery of additional objects in the Kuiper belt starting in the 1990s, and particularly the more massive ] object ] in 2005. In 2006, the ] (IAU) formally ] to exclude dwarf planets such as Pluto. Many planetary astronomers, however, continue to consider Pluto and other dwarf planets to be planets. | |||

| == History == | |||

| === Discovery === | |||

| {{further|Planets beyond Neptune}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In the 1840s, ] used ] to predict the position of the then-undiscovered planet ] after analyzing perturbations in the orbit of ]. Subsequent observations of Neptune in the late 19th century led astronomers to speculate that Uranus's orbit was being disturbed by another planet besides Neptune.<ref>{{cite book |last=Croswell |first=Ken |title=Planet Quest: The Epic Discovery of Alien Solar Systems |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=60sPD6yjbVAC |location=New York |publisher=The Free Press |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-684-83252-4 |page=43 |access-date=April 15, 2022 |archive-date=February 26, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240226151141/https://books.google.com/books?id=60sPD6yjbVAC |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1906, ]—a wealthy Bostonian who had founded ] in ], in 1894—started an extensive project in search of a possible ninth planet, which he termed "]".<ref name="Tombaugh1946" /> By 1909, Lowell and ] had suggested several possible celestial coordinates for such a planet.<ref name="Hoyt" /> Lowell and his observatory conducted his search, using mathematical calculations made by ], until his death in 1916, but to no avail. Unknown to Lowell, his surveys had captured two faint images of Pluto on March 19 and April 7, 1915, but they were not recognized for what they were.<ref name="Hoyt" /><ref name="Littman1990" /> There are fourteen other known ] observations, with the earliest made by the ] on August 20, 1909.<ref name="BuchwaldDimarioWild2000" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| Percival's widow, Constance Lowell, entered into a ten-year legal battle with the Lowell Observatory over her husband's legacy, and the search for Planet X did not resume until 1929.{{sfn|Croswell|1997|p=50}} ], the observatory director, gave the job of locating Planet X to 23-year-old ], who had just arrived at the observatory after Slipher had been impressed by a sample of his astronomical drawings.{{sfn|Croswell|1997|p=50}} | |||

| Tombaugh's task was to systematically image the night sky in pairs of photographs, then examine each pair and determine whether any objects had shifted position. Using a ], he rapidly shifted back and forth between views of each of the plates to create the illusion of movement of any objects that had changed position or appearance between photographs. On February 18, 1930, after nearly a year of searching, Tombaugh discovered a possible moving object on photographic plates taken on January 23 and 29. A lesser-quality photograph taken on January 21 helped confirm the movement.{{sfn|Croswell|1997|p=52}} After the observatory obtained further confirmatory photographs, news of the discovery was telegraphed to the ] on March 13, 1930.<ref name="Hoyt" /> | |||

| One Plutonian year corresponds to 247.94 Earth years;<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /> thus, in 2178, Pluto will complete its first orbit since its discovery. | |||

| === Name and symbol === | |||

| The name ''Pluto'' came from the Roman ]; and it is also an ] for ] (the Greek equivalent of Pluto). | |||

| Upon the announcement of the discovery, Lowell Observatory received over a thousand suggestions for names.<ref name="pluto guide" /> Three names topped the list: ], Pluto and ]. 'Minerva' was the Lowell staff's first choice<ref name=S&G/> but was rejected because it had already been used for ]; Cronus was disfavored because it was promoted by an unpopular and egocentric astronomer, ]. A vote was then taken and 'Pluto' was the unanimous choice. To make sure the name stuck, and that the planet would not suffer changes in its name as Uranus had, Lowell Observatory proposed the name to the ] and the ]; both approved it unanimously.<ref name=T&M>Clyde Tombaugh & Patrick Moore (2008) ''Out of the Darkness: The Planet Pluto''</ref>{{rp|136}}{{sfn|Croswell|1997|pp=54–55}} The name was published on May 1, 1930.<ref name="Venetia" /><ref>{{cite web |title=Pluto Research at Lowell |url=https://lowell.edu/in-depth/pluto/pluto-research-at-lowell/ |website=Lowell Observatory |access-date=March 22, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160418140312/http://lowell.edu/in-depth/pluto/pluto-research-at-lowell/ |archive-date=April 18, 2016 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| The name ''Pluto'' had received some 150 nominations among the letters and telegrams sent to Lowell. The first{{efn|A French astronomer had suggested the name ''Pluto'' for Planet X in 1919, but there is no indication that the Lowell staff knew of this.<ref>Ferris (2012: 336) ''Seeing in the Dark''</ref>}} had been from ] (1918–2009), an eleven-year-old schoolgirl in ], England, who was interested in ].<ref name=T&M/><ref name="Venetia" /> She had suggested it to her grandfather ] when he read the news of Pluto's discovery to his family over breakfast; Madan passed the suggestion to astronomy professor ], who cabled it to colleagues at Lowell on March 16, three days after the announcement.<ref name=S&G>Kevin Schindler & William Grundy (2018) ''Pluto and Lowell Observatory'', pp. 73–79.</ref><ref name="Venetia" /> | |||

| The name 'Pluto' was mythologically appropriate: the god Pluto was one of six surviving children of ], and the others had already all been chosen as names of major or minor planets (his brothers ] and ], and his sisters ], ] and ]). Both the god and the planet inhabited "gloomy" regions, and the god was able to make himself invisible, as the planet had been for so long.<ref>Scott & Powell (2018) ''The Universe as It Really Is''</ref> | |||

| The choice was further helped by the fact that the first two letters of ''Pluto'' were the initials of Percival Lowell; indeed, 'Percival' had been one of the more popular suggestions for a name for the new planet.<ref name=S&G/><ref>Coincidentally, as popular science author ] and others have noted of the name "Pluto", "the last two letters are the first two letters of Tombaugh's name" Martin Gardner, ''Puzzling Questions about the Solar System'' (Dover Publications, 1997) p. 55</ref> | |||

| Pluto's ] {{angbr|]}} was then created as a ] of the letters "PL".<ref name="JPL/NASA Pluto's Symbol" /> This symbol is rarely used in astronomy anymore,{{efn|name = PL |For example, {{angbr|♇}} (in ]: {{unichar|2647|PLUTO}}) occurs in a table of the planets identified by their symbols in a 2004 article written before the 2006 IAU definition,<ref>{{cite book |editor=John Lewis |date=2004 |title=Physics and chemistry of the solar system |edition= 2 |page=64 |publisher=Elsevier}}</ref> but not in a graph of planets, dwarf planets and moons from 2016, where only the eight IAU planets are identified by their symbols.<ref>{{cite journal |author1= Jingjing Chen |author2= David Kipping |year=2017 |title= Probabilistic Forecasting of the Masses and Radii of Other Worlds |journal= The Astrophysical Journal |volume= 834 |issue= 17 |page= 8 |publisher= The American Astronomical Society|doi= 10.3847/1538-4357/834/1/17 |arxiv= 1603.08614 |bibcode= 2017ApJ...834...17C |s2cid= 119114880 |doi-access= free }}</ref> | |||

| (Planetary symbols in general are uncommon in astronomy, and are discouraged by the IAU.)<ref name="iau_1989">{{cite book|date=1989|language=en|page=27|title=The IAU Style Manual|url=http://www.iau.org/static/publications/stylemanual1989.pdf|access-date=January 29, 2022|archive-date=July 26, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110726170213/http://www.iau.org/static/publications/stylemanual1989.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref>}} though it is still common in astrology. However, the most common ] for Pluto, occasionally used in astronomy as well, is an orb (possibly representing Pluto's invisibility cap) over Pluto's ] {{angbr|]}}, which dates to the early 1930s.<ref>Dane Rudhyar (1936) ''The Astrology of Personality'', credits it to Paul Clancy Publications, founded in 1933.</ref>{{efn|name = bident|The bident symbol ({{Unichar|2BD3|PLUTO FORM TWO}}) has seen some astronomical use as well since the IAU decision on dwarf planets, for example in a public-education poster on dwarf planets published by the NASA/JPL ''Dawn'' mission in 2015, in which each of the five dwarf planets announced by the IAU receives a symbol.<ref>NASA/JPL, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211208181916/https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/infographics/what-is-a-dwarf-planet |date=December 8, 2021 }} 2015 Apr 22</ref> There are in addition several other symbols for Pluto found in astrological sources,<ref>Fred Gettings (1981) ''Dictionary of Occult, Hermetic and Alchemical Sigils.'' Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.</ref> including three accepted by Unicode: ], {{unichar|2BD4|PLUTO FORM THREE}}, used principally in southern Europe; ]/], {{unichar|2BD6|PLUTO FORM FIVE}} (found in various orientations, showing Pluto's orbit cutting across that of Neptune), used principally in northern Europe; and ], {{unichar|2BD5|PLUTO FORM FOUR}}, used in ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Faulks |first1=David |title=Astrological Plutos |url=https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2016/16067r-astrological-plutos.pdf |website=www.unicode.org |publisher=Unicode |access-date=October 1, 2021 |archive-date=November 12, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201112010819/https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2016/16067r-astrological-plutos.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| The name 'Pluto' was soon embraced by wider culture. In 1930, ] was apparently inspired by it when he introduced for ] a canine companion named ], although ] animator ] could not confirm why the name was given.<ref name="Heinrichs2006" /> In 1941, ] named the newly created ] ] after Pluto, in keeping with the tradition of naming elements after newly discovered planets, following ], which was named after Uranus, and ], which was named after Neptune.<ref name="ClarkHobart2000" /> | |||

| Most languages use the name "Pluto" in various transliterations.{{efn|The equivalence is less close in languages whose ] differs widely from ], such as ] ''Buluuto'' and ] ''Tłóotoo''.}} In Japanese, ] suggested the ] {{nihongo3|"Star of the King (God) of the Underworld"|冥王星|Meiōsei}}, and this was borrowed into Chinese and Korean. Some ] use the name Pluto, but others, such as ], use the name of '']'', the God of Death in Hinduism.<ref name="nineplan" /> ] also tend to use the indigenous god of the underworld, as in ] '']''.<ref name="nineplan" /> | |||

| Vietnamese might be expected to follow Chinese, but does not because the ] word 冥 ''minh'' "dark" is homophonous with 明 ''minh'' "bright". Vietnamese instead uses Yama, which is also a Buddhist deity, in the form of ''Sao Diêm Vương'' 星閻王 "Yama's Star", derived from Chinese 閻王 '']'' "King Yama".<ref name="nineplan" /><ref name="RenshawIhara2000" /><ref name="Bathrobe" /> | |||

| === Planet X disproved === | |||

| Once Pluto was found, its faintness and lack of a ] cast doubt on the idea that it was Lowell's ].<ref name="Tombaugh1946" /> Estimates of Pluto's mass were revised downward throughout the 20th century.<ref>{{cite book|last1 = Stern|first1 = Alan|last2 = Tholen|first2 = David James|title = Pluto and Charon|date = 1997|publisher=University of Arizona Press|isbn = 978-0-8165-1840-1|pages=206–208}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable plainrowheaders" style="float: right; margin-right: 0; margin-left: 1em; text-align: center; clear:right;" | |||

| |+ Mass estimates for Pluto | |||

| ! scope="col" | Year | |||

| ! scope="col" | Mass | |||

| ! scope="col" | Estimate by | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | 1915 | |||

| | {{left|7 Earths}} | |||

| | ] (prediction for ])<ref name="Tombaugh1946" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | 1931 | |||

| | {{left|1 Earth}} | |||

| | ] & ]<ref name="RAS1931.91" /><ref name="Nicholson et al 1930">{{cite journal | |||

| | bibcode = 1930PASP...42..350N | |||

| | title = The Probable Value of the Mass of Pluto | |||

| | first1 = Seth B. | |||

| | last1 = Nicholson | |||

| | author-link1 = Seth B. Nicholson | |||

| | first2 = Nicholas U. | |||

| | last2 = Mayall | |||

| | author-link2 = Nicholas U. Mayall | |||

| | journal = Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific | |||

| | volume = 42 | |||

| | issue = 250 | |||

| | page = 350 | |||

| | date = December 1930 | |||

| | doi = 10.1086/124071 | |||

| | doi-access = free | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="Nicholson et al. 1931" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | 1948 | |||

| | {{left|0.1 (1/10) Earth}} | |||

| | ]<ref name="Kuiper 10.1086/126255" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | 1976 | |||

| | {{left|0.01 (1/100) Earth}} | |||

| | ], <!-- Carl -->Pilcher, & ]{{sfn|Croswell|1997|p=57}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | 1978 | |||

| | {{left|0.0015 (1/650) Earth}} | |||

| | ] & ]<ref name="ChristyHarrington1978" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | 2006 | |||

| | {{left|0.00218 (1/459) Earth}} | |||

| | ] et al.<!-- William M. Grundy, Eliot F. Young, Leslie A. Young, S. Alan Stern --><ref name="BuieGrundyYoung_2006" /> | |||

| |} | |||

| Astronomers initially calculated its mass based on its presumed effect on Neptune and Uranus. In 1931, Pluto was calculated to be roughly the mass of ], with further calculations in 1948 bringing the mass down to roughly that of ].<ref name="Nicholson et al 1930" /><ref name="Kuiper 10.1086/126255" /> In 1976, Dale Cruikshank, Carl Pilcher and David Morrison of the ] calculated Pluto's ] for the first time, finding that it matched that for methane ice; this meant Pluto had to be exceptionally luminous for its size and therefore could not be more than 1 percent the mass of Earth.{{sfn|Croswell|1997|p=57}} (Pluto's albedo is {{nowrap|1.4–1.9}} times that of Earth.<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" />) | |||

| In 1978, the discovery of Pluto's moon ] allowed the measurement of Pluto's mass for the first time: roughly 0.2% that of Earth, and far too small to account for the discrepancies in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent searches for an alternative Planet X, notably by ],<ref name="SeidelmannHarrington1988" /> failed. In 1992, ] used data from '']'''s flyby of Neptune in 1989, which had revised the estimates of Neptune's mass downward by 0.5%—an amount comparable to the mass of Mars—to recalculate its gravitational effect on Uranus. With the new figures added in, the discrepancies, and with them the need for a Planet X, vanished.<ref name="Standish1993" /> {{as of|2000}} the majority of scientists agree that Planet X, as Lowell defined it, does not exist.<ref name="Standage2000" /> Lowell had made a prediction of Planet X's orbit and position in 1915 that was fairly close to Pluto's actual orbit and its position at that time; ] concluded soon after Pluto's discovery that this was a coincidence.<ref>Ernest W. Brown, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220118073827/https://www.pnas.org/content/16/5/364 |date=January 18, 2022 }}, PNAS May 15, 1930, 16 (5) 364-371.</ref> | |||

| === Classification === | |||

| {{Further|Definition of planet}} | |||

| From 1992 onward, many bodies were discovered orbiting in the same volume as Pluto, showing that Pluto is part of a population of objects called the ]. This made its official status as a planet controversial, with many questioning whether Pluto should be considered together with or separately from its surrounding population. Museum and planetarium directors occasionally created controversy by omitting Pluto from planetary models of the ]. In February 2000 the ] in New York City displayed a Solar System model of only eight planets, which made headlines almost a year later.<ref name="Tyson2001" /> | |||

| ], ], ] and ] lost their planet status among most astronomers after the discovery of many other ]s in the 1840s. On the other hand, planetary geologists often regarded Ceres, and less often Pallas and Vesta, as being different from smaller asteroids because they were large enough to have undergone geological evolution.<ref name=metzger19>{{cite journal |last1=Metzger |first1=Philip T. |author-link1=Philip T. Metzger |last2=Sykes |first2=Mark V. |last3=Stern |first3=Alan |last4=Runyon |first4=Kirby |date=2019 |title=The Reclassification of Asteroids from Planets to Non-Planets |journal=Icarus |volume=319 |pages=21–32 |doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2018.08.026|arxiv=1805.04115 |bibcode=2019Icar..319...21M |s2cid=119206487 }}</ref> Although the first Kuiper belt objects discovered were quite small, objects increasingly closer in size to Pluto were soon discovered, some large enough (like Pluto itself) to satisfy geological but not dynamical ideas of planethood.<ref name=metzger22>{{cite journal |last1=Metzger |first1=Philip T. |author-link1=Philip T. Metzger |last2=Grundy |first2=W. M. |first3=Mark V. |last3=Sykes |first4=Alan |last4=Stern |first5=James F. |last5=Bell III |first6=Charlene E. |last6=Detelich |first7=Kirby |last7=Runyon |first8=Michael |last8=Summers |date=2022 |title=Moons are planets: Scientific usefulness versus cultural teleology in the taxonomy of planetary science |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103521004206 |journal=Icarus |volume=374 |issue= |page=114768 |doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114768 |arxiv=2110.15285 |bibcode=2022Icar..37414768M |s2cid=240071005 |access-date=August 8, 2022 |archive-date=September 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220911060134/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103521004206 |url-status=live }}</ref> On July 29, 2005, the debate became unavoidable when astronomers at ] announced the discovery of a new ], ], which was substantially more massive than Pluto and the most massive object discovered in the Solar System since ] in 1846. Its discoverers and the press initially called it the ], although there was no official consensus at the time on whether to call it a planet.<ref name="NASA-JPL press release 07-29-2005" /> Others in the astronomical community considered the discovery the strongest argument for reclassifying Pluto as a minor planet.<ref>{{cite journal |title=What Is a Planet? |journal=The Astronomical Journal |volume=132 |issue=6 |pages=2513–2519 |date=November 2, 2006 |doi=10.1086/508861 |last1 = Soter|first1 = Steven|bibcode=2006AJ....132.2513S |arxiv=astro-ph/0608359 |s2cid=14676169 }}</ref> | |||

| ==== IAU classification ==== | |||

| {{Main|IAU definition of planet}} | |||

| The debate came to a head in August 2006, with an ] that created an official definition for the term "planet". According to this resolution, there are three conditions for an object in the ] to be considered a planet: | |||

| * The object must be in orbit around the ]. | |||

| * The object must be massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity. More specifically, its own gravity should pull it into a shape defined by ]. | |||

| * It must have ] around its orbit.<ref name="IAU2006 GA26-5-6" /><ref name="IAU0603" /> | |||

| Pluto fails to meet the third condition.<ref name="Margot2015">{{cite journal|last1=Margot|first1=Jean-Luc|title=A Quantitative Criterion for Defining Planets|journal=The Astronomical Journal|volume=150|issue=6|year=2015|pages=185 |doi=10.1088/0004-6256/150/6/185|bibcode=2015AJ....150..185M|arxiv=1507.06300|s2cid=51684830}}</ref> Its mass is substantially less than the combined mass of the other objects in its orbit: 0.07 times, in contrast to Earth, which is 1.7 million times the remaining mass in its orbit (excluding the moon).<ref name="what" /><ref name="IAU0603" /> The IAU further decided that bodies that, like Pluto, meet criteria 1 and 2, but do not meet criterion 3 would be called ]s. In September 2006, the IAU included Pluto, and Eris and its moon ], in their ], giving them the official ]s "(134340) Pluto", "(136199) Eris", and "(136199) Eris I Dysnomia".<ref name="IAUC 8747" /> Had Pluto been included upon its discovery in 1930, it would have likely been designated 1164, following ], which was discovered a month earlier.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi#top |title=JPL Small-Body Database Browser |publisher=California Institute of Technology |access-date=July 15, 2015 |archive-date=July 21, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721054158/http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi#top |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| There has been some resistance within the astronomical community toward the reclassification, and in particular planetary scientists often continue to reject it, considering Pluto, Charon, and Eris to be planets for the same reason they do so for Ceres. In effect, this amounts to accepting only the second clause of the IAU definition.<ref name="geoff2006c" /><ref name="Ruibal-1999" /><ref name="Britt-2006" /> ], principal investigator with ]'s ''New Horizons'' mission to Pluto, derided the IAU resolution.<ref name="geoff2006a" /><ref name="newscientistspace" /> He also stated that because less than five percent of astronomers voted for it, the decision was not representative of the entire astronomical community.<ref name="newscientistspace" /> ], then at the Lowell Observatory, petitioned against the definition.<ref name="Buie2006 IAU response" /> Others have supported the IAU, for example ], the astronomer who discovered Eris.<ref name="Overbye2006" /> | |||

| Public reception to the IAU decision was mixed. A resolution introduced in the ] facetiously called the IAU decision a "scientific heresy".<ref name="DeVore2006" /> The ] passed a resolution in honor of Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto and a longtime resident of that state, that declared that Pluto will always be considered a planet while in New Mexican skies and that March 13, 2007, was Pluto Planet Day.<ref name="Holden2007" /><ref name="Gutierrez2007" /> The ] passed a similar resolution in 2009 on the basis that Tombaugh was born in Illinois. The resolution asserted that Pluto was "unfairly downgraded to a 'dwarf' planet" by the IAU."<ref name="ILGA SR0046" /> Some members of the public have also rejected the change, citing the disagreement within the scientific community on the issue, or for sentimental reasons, maintaining that they have always known Pluto as a planet and will continue to do so regardless of the IAU decision.<ref name="Sapa-AP" /> In 2006, in its 17th annual words-of-the-year vote, the ] voted '']'' as the word of the year. To "pluto" is to "demote or devalue someone or something".<ref name="msnbc" /> In April 2024, ] (where Pluto was first discovered in 1930) passed a law naming Pluto as the official state planet.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Sanchez |first1=Cameron |title=Pluto is a planet again — at least in Arizona |url=https://www.npr.org/2024/04/06/1243230463/pluto-was-discovered-at-an-arizona-observatory-it-might-be-named-the-state-plane |website=npr.org |publisher=NPR |access-date=April 12, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Researchers on both sides of the debate gathered in August 2008, at the Johns Hopkins University ] for a conference that included back-to-back talks on the IAU definition of a planet.<ref name="Minkel2008" /> Entitled "The Great Planet Debate",<ref name="The Great Planet Debate" /> the conference published a post-conference press release indicating that scientists could not come to a consensus about the definition of planet.<ref name="PSIedu press release 2008-09-19" /> In June 2008, the IAU had announced in a press release that the term "]" would henceforth be used to refer to Pluto and other planetary-mass objects that have an orbital ] greater than that of Neptune, though the term has not seen significant use.<ref name="IAU0804" /><ref name="Discover 2009-JANp76" /><ref name="Science News, July 5, 2008 p. 7" /> | |||

| == Orbit == | |||

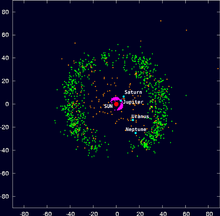

| ] | |||

| Pluto's orbital period is about 248 years. Its orbital characteristics are substantially different from those of the planets, which follow nearly circular orbits around the Sun close to a flat reference ] called the ]. In contrast, Pluto's orbit is moderately ] relative to the ecliptic (over 17°) and moderately ] (elliptical). This eccentricity means a small region of Pluto's orbit lies closer to the Sun than Neptune's. The Pluto–Charon barycenter came to ] on September 5, 1989,<ref name="jpl-ssd-horizons" />{{efn|name = Perihelion}} and was last closer to the Sun than Neptune between February 7, 1979, and February 11, 1999.<ref name="pluto990209" /> | |||

| Although the 3:2 resonance with Neptune (see below) is maintained, Pluto's inclination and eccentricity behave in a ] manner. Computer simulations can be used to predict its position for several million years (both ] in time), but after intervals much longer than the ] of 10–20 million years, calculations become unreliable: Pluto is sensitive to immeasurably small details of the Solar System, hard-to-predict factors that will gradually change Pluto's position in its orbit.<ref name="sussman88" /><ref name="wisdom91" /> | |||

| The ] of Pluto's orbit varies between about 39.3 and 39.6 ] with a period of about 19,951 years, corresponding to an orbital period varying between 246 and 249 years. The semi-major axis and period are presently getting longer.<ref name=williams71 /> | |||

| === Relationship with Neptune <span class="anchor" id="Orbits of Pluto and Neptune"></span> === | |||

| ]. Neptune is seen orbiting close to the ecliptic.]] | |||

| Despite Pluto's orbit appearing to cross that of Neptune when viewed from north or south of the Solar System, the two objects' orbits do not intersect. When Pluto is closest to the Sun, and close to Neptune's orbit as viewed from such a position, it is also the farthest north of Neptune's path. Pluto's orbit passes about 8 ] north of that of Neptune, preventing a collision.<ref name="huainn01" /><ref name="Hunter2004" /><ref name="malhotra-9planets" />{{efn|Because of the eccentricity of Pluto's orbit, some have theorized that it was once a ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Sagan|first1=Carl|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LhkoowKFaTsC|title=Comet|last2=Druyan|first2=Ann|publisher=Random House|year=1997|isbn=978-0-3078-0105-0|location=New York|page=223|author-link1=Carl Sagan|author-link2=Ann Druyan|name-list-style=amp|access-date=October 18, 2021|archive-date=February 26, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240226151129/https://books.google.com/books?id=LhkoowKFaTsC|url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| This alone is not enough to protect Pluto; ] from the planets (especially Neptune) could alter Pluto's orbit (such as its ]) over millions of years so that a collision could happen. However, Pluto is also protected by its 2:3 ] with ]: for every two orbits that Pluto makes around the Sun, Neptune makes three, in a frame of reference that rotates at the rate that Pluto's perihelion precesses (about {{value|0.97e-4}} degrees per year<ref name=williams71/>). Each cycle lasts about 495 years. (There are many other objects in this same resonance, called ]s.) At present, in each 495-year cycle, the first time Pluto is at ] (such as in 1989), Neptune is 57° ahead of Pluto. By Pluto's second passage through perihelion, Neptune will have completed a further one and a half of its own orbits, and will be 123° behind Pluto.<ref name=Horizons>The {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240213103809/https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons_batch.cgi?batch=1&COMMAND=%27134340%27&START_TIME=%271700-1-7%27&STOP_TIME=%272097-12-31%27&STEP_SIZE=%271461%20days%27&QUANTITIES=%2718%2019%27 |date=February 13, 2024 }} and {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240213103809/https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons_batch.cgi?batch=1&COMMAND=%27899%27&START_TIME=%271700-1-7%27&STOP_TIME=%272097-12-31%27&STEP_SIZE=%271461%20days%27&QUANTITIES=%2718%2019%27 |date=February 13, 2024 }} are available from the ].</ref> Pluto and Neptune's minimum separation is over 17 AU, which is greater than Pluto's minimum separation from Uranus (11 AU).<ref name="malhotra-9planets" /> The minimum separation between Pluto and Neptune actually occurs near the time of Pluto's aphelion.<ref name=williams71 /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The 2:3 resonance between the two bodies is highly stable and has been preserved over millions of years.<ref name="sp-345" /> This prevents their orbits from changing relative to one another, so the two bodies can never pass near each other. Even if Pluto's orbit were not inclined, the two bodies could never collide.<ref name="malhotra-9planets" /> When Pluto's period is slightly different from 3/2 of Neptune's, the pattern of its distance from Neptune will drift. Near perihelion Pluto moves interior to Neptune's orbit and is therefore moving faster, so during the first of two orbits in the 495-year cycle, it is approaching Neptune from behind. At present it remains between 50° and 65° behind Neptune for 100 years (e.g. 1937–2036).<ref name=Horizons/> The gravitational pull between the two causes ] to be transferred to Pluto. This situation moves Pluto into a slightly larger orbit, where it has a slightly longer period, according to ]. After several such repetitions, Pluto is sufficiently delayed that at the second perihelion of each cycle it will not be far ahead of Neptune coming behind it, and Neptune will start to decrease Pluto's period again. The whole cycle takes about 20,000 years to complete.<ref name="malhotra-9planets" /><ref name="sp-345" /><ref name="Cohen_Hubbard_1965">{{cite journal|last1=Cohen|first1=C. J.|last2=Hubbard|first2=E. C.|title=Libration of the close approaches of Pluto to Neptune|journal=Astronomical Journal|date=1965|volume=70|page=10|doi=10.1086/109674|bibcode=1965AJ.....70...10C|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Other factors ==== | |||

| Numerical studies have shown that over millions of years, the general nature of the alignment between the orbits of Pluto and Neptune does not change.<ref name="huainn01" /><ref name="williams71" /> There are several other resonances and interactions that enhance Pluto's stability. These arise principally from two additional mechanisms (besides the 2:3 mean-motion resonance). | |||

| First, Pluto's ], the angle between the point where it crosses the ecliptic (or the ]) and the point where it is closest to the Sun, ] around 90°.<ref name="williams71" /> This means that when Pluto is closest to the Sun, it is at its farthest north of the plane of the Solar System, preventing encounters with Neptune. This is a consequence of the ],<ref name="huainn01" /> which relates the eccentricity of an orbit to its inclination to a larger perturbing body—in this case, Neptune. Relative to Neptune, the amplitude of libration is 38°, and so the angular separation of Pluto's perihelion to the orbit of Neptune is always greater than 52° {{nowrap|(90°–38°)}}. The closest such angular separation occurs every 10,000 years.<ref name="sp-345" /> | |||

| Second, the longitudes of ascending nodes of the two bodies—the points where they cross the ]—are in near-resonance with the above libration. When the two longitudes are the same—that is, when one could draw a straight line through both nodes and the Sun—Pluto's perihelion lies exactly at 90°, and hence it comes closest to the Sun when it is furthest north of Neptune's orbit. This is known as the ''1:1 superresonance''. All the ] (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) play a role in the creation of the superresonance.<ref name="huainn01" /> | |||

| ===Orcus=== | |||

| The second-largest known ], ], has a diameter around 900 km and is in a very similar orbit to that of Pluto. However, the orbits of Pluto and Orcus are out of phase, so that the two never approach each other. It has been termed the "anti-Pluto", and is named for the ]. | |||

| == Rotation == | |||

| ] | |||

| Pluto's ], its day, is equal to 6.387 ] days.<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet" /><ref name="axis" /> Like ] and ], Pluto rotates on its "side" in its orbital plane, with an axial tilt of 120°, and so its seasonal variation is extreme; at its ]s, one-fourth of its surface is in continuous daylight, whereas another fourth is in continuous darkness.<ref name="Oregon" /> The reason for this unusual orientation has been debated. Research from the ] has suggested that it may be due to the way that a body's spin will always adjust to minimize energy. This could mean a body reorienting itself to put extraneous mass near the equator and regions lacking mass tend towards the poles. This is called '']''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Kirschvink|first1=Joseph L.|last2=Ripperdan|first2=Robert L.|last3=Evans|first3=David A.|date=July 25, 1997|title=Evidence for a Large-Scale Reorganization of Early Cambrian Continental Masses by Inertial Interchange True Polar Wander|journal=Science|language=en|volume=277|issue=5325|pages=541–545|doi=10.1126/science.277.5325.541|s2cid=177135895|issn=0036-8075}}</ref> According to a paper released from the University of Arizona, this could be caused by masses of frozen nitrogen building up in shadowed areas of the dwarf planet. These masses would cause the body to reorient itself, leading to its unusual axial tilt of 120°. The buildup of nitrogen is due to Pluto's vast distance from the Sun. At the equator, temperatures can drop to {{convert|-240|C|F K}}, causing nitrogen to freeze as water would freeze on Earth. The same polar wandering effect seen on Pluto would be observed on Earth were the ] several times larger.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Keane|first1=James T.|last2=Matsuyama|first2=Isamu|last3=Kamata|first3=Shunichi|last4=Steckloff|first4=Jordan K.|title=Reorientation and faulting of Pluto due to volatile loading within Sputnik Planitia|journal=Nature|volume=540|issue=7631|pages=90–93|doi=10.1038/nature20120|pmid=27851731|bibcode = 2016Natur.540...90K |year=2016|s2cid=4468636}}</ref> | |||

| == Geology == | |||

| {{Main|Geology of Pluto|Geography of Pluto}} | |||

| === Surface === | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The plains on Pluto's surface are composed of more than 98 percent ], with traces of methane and ].<ref name="tobias" /> ] and carbon monoxide are most abundant on the anti-Charon face of Pluto (around 180° longitude, where ]'s western lobe, ], is located), whereas methane is most abundant near 300° east.<ref name=Grundy_2013 /> The mountains are made of water ice.<ref name="drake-natgeo">{{cite magazine | url = http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/11/151109-astronomy-pluto-nasa-new-horizons-volcano-moons-science/| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151113013310/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/11/151109-astronomy-pluto-nasa-new-horizons-volcano-moons-science/| url-status = dead| archive-date = November 13, 2015| title = Floating Mountains on Pluto – You Can't Make This Stuff Up| last = Drake| first = Nadia| author-link = Nadia Drake | date = November 9, 2015| magazine = ]| access-date = December 23, 2016}}</ref> Pluto's surface is quite varied, with large differences in both brightness and color.<ref name="Buie_2010 light curve" /> Pluto is one of the most contrastive bodies in the Solar System, with as much contrast as ]'s moon ].<ref name="Buie_web_map" /> The color varies from charcoal black, to dark orange and white.<ref name="Hubble2010" /> Pluto's color is more similar to that of ] with slightly more orange and significantly less red than ].<ref name="Buie_2010 surface-maps" /> ] include Tombaugh Regio, or the "Heart" (a large bright area on the side opposite Charon), ],<ref name = "Pluto System after New Horizons"/> or the "Whale" (a large dark area on the trailing hemisphere), and the "]" (a series of equatorial dark areas on the leading hemisphere). | |||

| Sputnik Planitia, the western lobe of the "Heart", is a 1,000 km-wide basin of frozen nitrogen and carbon monoxide ices, divided into polygonal cells, which are interpreted as ]s that carry floating blocks of water ice crust and ] pits towards their margins;<ref name="lakdawalla-DPS-2016-10-26">{{cite web| url = http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/10251718-dpsepsc-new-horizons-pluto.html| title = DPS/EPSC update on New Horizons at the Pluto system and beyond| last = Lakdawalla| first = Emily| author-link = Emily Lakdawalla| date = October 26, 2016| publisher = ]| access-date = October 26, 2016| archive-date = October 8, 2018| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20181008021643/http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/10251718-dpsepsc-new-horizons-pluto.html| url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="McKinnon2016">{{cite journal|last1=McKinnon|first1=W. B.|last2=Nimmo|first2= F.|last3=Wong|first3= T.|last4= Schenk|first4=P. M.|last5=White|first5=O. L.|last6=Roberts|first6=J. H.|last7=Moore|first7=J. M.|last8=Spencer|first8=J. R.|last9=Howard|first9=A. D.|last10=Umurhan|first10=O. M.|last11= Stern|first11=S. A.|last12=Weaver|first12=H. A.|last13= Olkin|first13=C. B.|last14=Young|first14=L. A.|last15= Smith|first15=K. E.|last16=Beyer|first16= R.|last17= Buie|first17= M.|last18=Buratti|first18= B.|last19= Cheng|first19= A.|last20=Cruikshank|first20=D.|last21=Dalle Ore|first21= C.|last22= Gladstone|first22= R.|last23= Grundy|first23= W.|last24=Lauer|first24=T.|last25=Linscott|first25= I.|last26= Parker|first26= J.|last27=Porter|first27= S.|last28= Reitsema|first28= H.|last29=Reuter|first29= D.|last30= Robbins|first30= S.|last31= Showalter|first31= M.|last32= Singer|first32= K.|last33=Strobel|first33= D.|last34= Summers|first34= M.|last35= Tyler|first35= L.|last36= Banks|first36= M.|last37=Barnouin|first37= O.|last38= Bray|first38= V.|last39= Carcich|first39= B.|last40=Chaikin|first40= A.|last41= Chavez|first41=C.|last42= Conrad|first42= C.|last43= Hamilton|first43= D.|last44= Howett|first44= C.|last45=Hofgartner|first45= J.|last46= Kammer|first46= J.|last47= Lisse|first47= C.|last48= Marcotte|first48= A.|last49=Parker|first49= A.|last50= Retherford|first50= K.|last51=Saina|first51= M.|last52= Runyon|first52= K.|last53=Schindhelm|first53= E.|last54= Stansberry|first54= J.|last55= Steffl|first55= A.|last56= Stryk|first56=T.|last57=Throop|first57=H.|last58=Tsang|first58=C.|last59=Verbiscer|first59=A.|last60=Winters|first60=H.|last61=Zangari|first61=A.|display-authors=5|title=Convection in a volatile nitrogen-ice-rich layer drives Pluto's geological vigour|journal= Nature|volume=534|issue= 7605|date=June 1, 2016|pages= 82–85|doi= 10.1038/nature18289|pmid=27251279|bibcode = 2016Natur.534...82M |arxiv=1903.05571|s2cid=30903520}}</ref><ref name="Trowbridge2016">{{cite journal|last1=Trowbridge|first1=A. J.|last2= Melosh|first2=H. J.|last3= Steckloff|first3= J. K.|last4=Freed|first4=A. M.|title=Vigorous convection as the explanation for Pluto's polygonal terrain|journal= Nature|volume= 534|issue=7605|date= June 1, 2016|pages=79–81|doi=10.1038/nature18016|pmid=27251278|bibcode = 2016Natur.534...79T |s2cid=6743360 }}</ref> there are obvious signs of glacial flows both into and out of the basin.<ref name="Pluto updates">{{cite web| url = http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/12211538-pluto-updates-from-agu.html| title = Pluto updates from AGU and DPS: Pretty pictures from a confusing world| last = Lakdawalla| first = Emily| author-link = Emily Lakdawalla| date = December 21, 2015| publisher = ]| access-date = January 24, 2016| archive-date = December 24, 2015| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151224193036/http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/12211538-pluto-updates-from-agu.html| url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="Umurhan2016-01-08">{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://blogs.nasa.gov/pluto/2016/01/08/probing-the-mysterious-glacial-flow-on-plutos-frozen-heart/ | |||

| | title = Probing the Mysterious Glacial Flow on Pluto's Frozen 'Heart' | |||

| | last = Umurhan | |||

| | first = O. | |||

| | date = January 8, 2016 | |||

| | website = blogs.nasa.gov | |||

| | publisher = NASA | |||

| | access-date = January 24, 2016 | |||

| | archive-date = April 19, 2016 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160419182828/https://blogs.nasa.gov/pluto/2016/01/08/probing-the-mysterious-glacial-flow-on-plutos-frozen-heart/ | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> It has no craters that were visible to ''New Horizons'', indicating that its surface is less than 10 million years old.<ref name="Marchis2016">{{cite journal|last1=Marchis|first1=F.|last2=Trilling|first2=D. E.|title=The Surface Age of Sputnik Planum, Pluto, Must Be Less than 10 Million Years|journal=PLOS ONE|volume= 11|issue=1|date= January 20, 2016|pages= e0147386|doi= 10.1371/journal.pone.0147386|arxiv = 1601.02833 |bibcode = 2016PLoSO..1147386T|pmid=26790001|pmc=4720356|doi-access=free}}</ref> Latest studies have shown that the surface has an age of {{val|180000|-90000|+40000}} years.<ref name="LPSC2017Buhler">{{cite conference|last1=Buhler|first1=P. B.|last2=Ingersoll|first2=A. P.|url=https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2017/pdf/1746.pdf|title=Sublimation pit distribution indicates convection cell surface velocity of ~10 centimeters per year in Sputnik Planitia, Pluto|book-title=48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference|date=March 23, 2017|access-date=May 11, 2017|archive-date=August 13, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170813010426/https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2017/pdf/1746.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The New Horizons science team summarized initial findings as "Pluto displays a surprisingly wide variety of geological landforms, including those resulting from ] and surface–atmosphere interactions as well as impact, ], possible ], and ] processes."<ref name="Stern2015" /> | |||

| In Western parts of Sputnik Planitia there are fields of ] formed by the winds blowing from the center of Sputnik Planitia in the direction of surrounding mountains. The dune wavelengths are in the range of 0.4–1 km and likely consist of methane particles 200–300 μm in size.<ref name="Brown2018">{{cite journal|doi=10.1126/science.aao2975|pmid=29853681|title=Dunes on Pluto|journal=Science|volume=360|issue=6392|pages=992–997|year=2018|last1=Telfer|first1=Matt W|last2=Parteli|first2=Eric J. R|last3=Radebaugh|first3=Jani|last4=Beyer|first4=Ross A|last5=Bertrand|first5=Tanguy|last6=Forget|first6=François|last7=Nimmo|first7=Francis|last8=Grundy|first8=Will M|last9=Moore|first9=Jeffrey M|last10=Stern|first10=S. Alan|last11=Spencer|first11=John|last12=Lauer|first12=Tod R|last13=Earle|first13=Alissa M|last14=Binzel|first14=Richard P|last15=Weaver|first15=Hal A|last16=Olkin|first16=Cathy B|last17=Young|first17=Leslie A|last18=Ennico|first18=Kimberly|last19=Runyon|first19=Kirby|bibcode=2018Sci...360..992T|s2cid=44159592|url=https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/10026.1/11613/UoP_Deposit_Agreement%20v1.1%2020160217.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y|doi-access=free|access-date=April 12, 2020|archive-date=October 23, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201023114119/https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/10026.1/11613/UoP_Deposit_Agreement%20v1.1%2020160217.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery mode=packed heights=160> | |||

| File:Pluto-01 Stern 03 Pluto Color TXT.jpg|Multispectral Visual Imaging Camera image of Pluto in enhanced color to bring out differences in surface composition | |||

| File:Pluto_Charon_crater_map_Robbins_Dones_2023.jpg|Distribution of numerous impact craters and basins on both Pluto and Charon. The variation in density (with none found in ]) indicates a long history of varying geological activity. Precisely for this reason, the confidence of numerous craters on Pluto remain uncertain.<ref name="Robbins2023"/> The lack of craters on the left and right of each map is due to low-resolution coverage of those anti-encounter regions. | |||

| File:Pluto's Sputnik Planum geologic map (cropped).jpg|Geologic map of Sputnik Planitia and surroundings (]), with ] margins outlined in black | |||

| NH-Pluto-WaterIceDetected-BlueRegions-Released-20151008.jpg|Regions where water ice has been detected (blue regions) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Internal structure === | |||

| {{redirect|Life on Pluto|fiction about aliens from Pluto|Life on Pluto in fiction}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Pluto's density is {{val|1.853|0.004|u=g/cm3}}.<ref name="Brozovic2024"/> Because the decay of radioactive elements would eventually heat the ices enough for the rock to separate from them, scientists expect that Pluto's internal structure is differentiated, with the rocky material having settled into a dense ] surrounded by a ] of water ice. The pre–''New Horizons'' estimate for the diameter of the core is {{val|1,700|u=km}}, 70% of Pluto's diameter.<ref name="Hussmann2006" /> | |||

| It is possible that such heating continues, creating a ] of liquid water {{nowrap|100 to 180 km}} thick at the core–mantle boundary.<ref name="Hussmann2006" /><ref name="pluto.jhuapl Inside Story" /><ref name="Sci Am 2017"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181226133924/https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/overlooked-ocean-worlds-fill-the-outer-solar-system/ |date=December 26, 2018 }}. John Wenz, ''Scientific American''. October 4, 2017.</ref> In September 2016, scientists at ] simulated the impact thought to have formed ], and showed that it might have been the result of liquid water upweling from below after the collision, implying the existence of a subsurface ocean at least 100 km deep.<ref>{{cite magazine|title=An Incredibly Deep Ocean Could Be Hiding Beneath Pluto's Icy Heart|author=Samantha Cole|url=http://www.popsci.com/an-incredibly-deep-ocean-could-be-hiding-beneath-plutos-icy-heart|magazine=Popular Science|access-date=September 24, 2016|archive-date=September 27, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160927112125/http://www.popsci.com/an-incredibly-deep-ocean-could-be-hiding-beneath-plutos-icy-heart|url-status=live}}</ref> In June 2020, astronomers reported evidence that Pluto may have had a ], and consequently may have been ], when it was first formed.<ref name="INV-20200622">{{cite news |last=Rabie |first=Passant |title=New Evidence Suggests Something Strange and Surprising about Pluto{{dash}}The findings will make scientists rethink the habitability of Kuiper Belt objects. |url=https://www.inverse.com/science/pluto-hot-star |date=June 22, 2020 |work=] |access-date=June 23, 2020 |archive-date=June 23, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200623071829/https://www.inverse.com/science/pluto-hot-star |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NGS-20200622">{{cite journal |author=Bierson, Carver |display-authors=et al. |title=Evidence for a hot start and early ocean formation on Pluto |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-020-0595-0 |date=June 22, 2020 |journal=] |volume=769 |issue=7 |pages=468–472 |doi=10.1038/s41561-020-0595-0 |bibcode=2020NatGe..13..468B |s2cid=219976751 |access-date=June 23, 2020 |url-access=subscription |archive-date=June 22, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200622201613/https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-020-0595-0 |url-status=live }}</ref> In March 2022, a team of researchers proposed that the mountains ] and ] are actually a merger of many smaller cryovolcanic domes, suggesting a source of heat on the body at levels previously thought not possible.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Large-scale cryovolcanic resurfacing on Pluto |first=Kelsi N. |last=Singer |journal=] |date=March 29, 2022 |volume=13 |issue=1 |page=1542 |doi=10.1038/s41467-022-29056-3 |pmid=35351895 |pmc=8964750 |arxiv=2207.06557 |bibcode=2022NatCo..13.1542S }}</ref> | |||

| == Mass and size == | |||

| ]Pluto's diameter is {{val|2376.6|3.2|u=km}}<ref name="Nimmo2017" /> and its mass is {{val|1.303|0.003|e=22|u=kg}}, 17.7% that of the ] (0.22% that of Earth).<ref name="Davies2001" /> Its ] is {{val|1.774443|e=7|u=km2}}, or just slightly bigger than Russia or ] (particularly including the ] during winter). Its ] is 0.063 ''g'' (compared to 1 ''g'' for Earth and 0.17 ''g'' for the Moon).<ref name="Pluto Fact Sheet"/> This gives Pluto an escape velocity of 4,363.2 km per hour / 2,711.167 miles per hour (as compared to Earth's 40,270 km per hour / 25,020 miles per hour). Pluto is more than twice the diameter and a dozen times the mass of ], the largest object in the ]. It is less massive than the dwarf planet ], a ] discovered in 2005, though Pluto has a larger diameter of 2,376.6 km<ref name="Nimmo2017" /> compared to Eris's approximate diameter of 2,326 km.<ref name="NewHorizons_PlutoSize">{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/feature/how-big-is-pluto-new-horizons-settles-decades-long-debate |title=How Big Is Pluto? New Horizons Settles Decades-Long Debate |publisher=NASA |date=July 13, 2015 |access-date=July 13, 2015 |archive-date=July 1, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170701005734/https://www.nasa.gov/feature/how-big-is-pluto-new-horizons-settles-decades-long-debate/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| With less than 0.2 lunar masses, Pluto is much less massive than the ]s, and also less massive than seven ]: ], ], ], ], the ], ], and ]. The mass is much less than thought before Charon was discovered.<ref>{{cite web |title=Pluto and Charon {{!}} Astronomy |url=https://courses.lumenlearning.com/astronomy/chapter/pluto-and-charon/ |website=courses.lumenlearning.com |access-date=April 6, 2022 |quote=For a long time, it was thought that the mass of Pluto was similar to that of Earth, so that it was classed as a fifth terrestrial planet, somehow misplaced in the far outer reaches of the solar system. There were other anomalies, however, as Pluto's orbit was more eccentric and inclined to the plane of our solar system than that of any other planet. Only after the discovery of its moon Charon in 1978 could the mass of Pluto be measured, and it turned out to be far less than the mass of Earth. |archive-date=March 24, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220324145506/https://courses.lumenlearning.com/astronomy/chapter/pluto-and-charon/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The discovery of Pluto's satellite ] in 1978 enabled a determination of the mass of the Pluto–Charon system by application of ]. Observations of Pluto in ] with Charon allowed scientists to establish Pluto's diameter more accurately, whereas the invention of ] allowed them to determine its shape more accurately.<ref name="Close_2000" /> | |||

| Determinations of Pluto's size have been complicated by its atmosphere<ref name="Young2007" /> and ] haze.<ref name="Plutosize" /> In March 2014, Lellouch, de Bergh et al. published findings regarding methane mixing ratios in Pluto's atmosphere consistent with a Plutonian diameter greater than 2,360 km, with a "best guess" of 2,368 km.<ref name=Lellouch_2015 /> On July 13, 2015, images from NASA's ''New Horizons'' mission ] (LORRI), along with data from the other instruments, determined Pluto's diameter to be {{convert|2370|km|abbr=on|sigfig=4}},<ref name = NewHorizons_PlutoSize /><ref name="emily">{{cite web |last1=Lakdawalla |first1=Emily |title=Pluto minus one day: Very first New Horizons Pluto encounter science results |url=http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/07131311-pluto-first-science.html |publisher=] |date=July 13, 2015 |access-date=July 13, 2015 |archive-date=March 2, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200302200913/https://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/07131311-pluto-first-science.html |url-status=live }}</ref> which was later revised to be {{convert|2372|km|abbr=on}} on July 24,<ref name="NHPC_20150724">{{cite AV media |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWr29KIs2Ns |title=NASA's New Horizons Team Reveals New Scientific Findings on Pluto |date=July 24, 2015 |publisher=NASA |time=52:30 |access-date=July 30, 2015 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211028/dWr29KIs2Ns |archive-date=October 28, 2021 |quote=We had an uncertainty that ranged over maybe 70 kilometers, we've collapsed that to plus and minus two, and it's centered around 1186}}{{cbignore}}</ref> and later to {{val|2374|8|u=km}}.<ref name="Stern2015" /> Using ] data from the ''New Horizons'' Radio Science Experiment (REX), the diameter was found to be {{val|2376.6|3.2|u=km}}.<ref name="Nimmo2017" /> | |||

| {{image frame | |||

| |content={{Graph:Chart | |||

| | width=400 | |||

| | height=200 | |||

| | type=rect | |||

| | x=Triton,Eris,Pluto,Haumea,Titania,Makemake,Oberon,Rhea,Iapetus,Gonggong,Charon,Quaoar,Ceres,Orcus | |||

| | y1=21.39,16.6,13.03,4.01,3.40,3.1,3.08,2.307,1.806,1.75,1.59,1.4,0.94,0.61 | |||

| | showValues=format:.1f, offset:1 | |||

| | xAxisAngle=45 | |||

| }} | |||

| |width=440 | |||

| |caption=The masses of Pluto and Charon compared to other dwarf planets ({{dp|Eris}}, {{dp|Haumea}}, {{dp|Makemake}}, {{dp|Gonggong}}, {{dp|Quaoar}}, {{dp|Orcus}}, {{dp|Ceres}}) and to the icy moons Triton (Neptune I), Titania (Uranus III), Oberon (Uranus IV), Rhea (Saturn V) and Iapetus (Saturn VIII). The unit of mass is {{e|21}} kg. | |||

| |border=no | |||

| }}{{Clear}} | |||

| == Atmosphere == | |||

| {{Main|Atmosphere of Pluto}} | |||

| ]Pluto has a tenuous ] consisting of ] (N<sub>2</sub>), ] (CH<sub>4</sub>), and carbon monoxide (CO), which are in ] on Pluto's surface.<ref name="NYT-20150724-ap">{{cite news |title=Conditions on Pluto: Incredibly Hazy With Flowing Ice |url=https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2015/07/24/science/ap-us-sci-pluto.html |date=July 24, 2015 |work=] |access-date=July 24, 2015 |archive-date=July 28, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150728081402/http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2015/07/24/science/ap-us-sci-pluto.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Croswell1992" /> According to the measurements by ''New Horizons'', the surface pressure is about 1 ] (10 ]),<ref name=Stern2015 /> roughly one million to 100,000 times less than Earth's atmospheric pressure. It was initially thought that, as Pluto moves away from the Sun, its atmosphere should gradually freeze onto the surface; studies of ''New Horizons'' data and ground-based occultations show that Pluto's atmospheric density increases, and that it likely remains gaseous throughout Pluto's orbit.<ref name=Olkin_2015 /><ref name="skyandtel">{{cite news|title=Pluto's Atmosphere Confounds Researchers|author=Kelly Beatty|newspaper=Sky & Telescope|year=2016|url=http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/plutos-atmosphere-confounds-researchers-032520166/|access-date=April 2, 2016|archive-date=April 7, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160407162627/http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/plutos-atmosphere-confounds-researchers-032520166/|url-status=live}}</ref> ''New Horizons'' observations showed that atmospheric escape of nitrogen to be 10,000 times less than expected.<ref name=skyandtel /> Alan Stern has contended that even a small increase in Pluto's surface temperature can lead to exponential increases in Pluto's atmospheric density; from 18 hPa to as much as 280 hPa (three times that of Mars to a quarter that of the Earth). At such densities, nitrogen could flow across the surface as liquid.<ref name=skyandtel /> Just like sweat cools the body as it evaporates from the skin, the ] of Pluto's atmosphere cools its surface.<ref name="KerThan2006-CNN" /> Pluto has no or almost no ]; observations by ''New Horizons'' suggest only a thin tropospheric ]. Its thickness in the place of measurement was 4 km, and the temperature was 37±3 K. The layer is not continuous.<ref name=Gladstone_2016>{{cite journal |title=The atmosphere of Pluto as observed by New Horizons |last1=Gladstone |first1=G. R. |last2=Stern |first2=S. A. |last3=Ennico |first3=K. |display-authors=etal |date=March 2016 |journal=Science |volume=351 |issue=6279 |doi=10.1126/science.aad8866 |bibcode=2016Sci...351.8866G |arxiv=1604.05356 |url=https://www.astro.umd.edu/~dphamil/research/reprints/GlaSteEnn16.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160521090831/https://www.astro.umd.edu/~dphamil/research/reprints/GlaSteEnn16.pdf |archive-date=May 21, 2016 |pages=aad8866 |pmid=26989258 |s2cid=32043359 |access-date=June 12, 2016}} ()</ref> | |||

| In July 2019, an occultation by Pluto showed that its atmospheric pressure, against expectations, had fallen by 20% since 2016.<ref>{{cite web|title=What is happening to Pluto's Atmosphere|url=https://astronomy.com/news/2020/05/plutos-strange-atmosphere-just-collapsed|date=May 22, 2020|access-date=October 7, 2021|archive-date=October 24, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211024063219/https://astronomy.com/news/2020/05/plutos-strange-atmosphere-just-collapsed|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2021, astronomers at the ] confirmed the result using data from an occultation in 2018, which showed that light was appearing less gradually from behind Pluto's disc, indicating a thinning atmosphere.<ref>{{cite web|title=SwRI Scientists Confirm Decrease In Pluto's Atmospheric Density|url=https://www.swri.org/press-release/scientists-confirm-decrease-plutos-atmospheric-density|date=October 4, 2021|work=Southwest Research Institute|access-date=October 7, 2021|archive-date=October 15, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211015201003/https://www.swri.org/press-release/scientists-confirm-decrease-plutos-atmospheric-density|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The presence of methane, a powerful ], in Pluto's atmosphere creates a ], with the average temperature of its atmosphere tens of degrees warmer than its surface,<ref name=Lellouch_2009 /> though observations by ''New Horizons'' have revealed Pluto's upper atmosphere to be far colder than expected (70 K, as opposed to about 100 K).<ref name=skyandtel /> Pluto's atmosphere is divided into roughly 20 regularly spaced haze layers up to 150 km high,<ref name=Stern2015 /> thought to be the result of pressure waves created by airflow across Pluto's mountains.<ref name=skyandtel /> | |||

| == Natural satellites == | |||

| {{main|Moons of Pluto}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Pluto has five known ]s. The largest and closest to Pluto is ]. First identified in 1978 by astronomer ], Charon is the only moon of Pluto that may be in ]. Charon's mass is sufficient to cause the barycenter of the Pluto–Charon system to be outside Pluto. Beyond Charon there are four much smaller ] moons. In order of distance from Pluto they are Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. ] and ] were both discovered in 2005,<ref name="Gugliotta2005" /> ] was discovered in 2011,<ref name="P4" /> and ] was discovered in 2012.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.space.com/16531-pluto-fifth-moon-hubble-discovery.html |title=Pluto Has a Fifth Moon, Hubble Telescope Reveals |last=Wall |first=Mike |date=July 11, 2012 |work=Space.com |access-date=July 11, 2012 |archive-date=May 14, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200514184955/https://www.space.com/16531-pluto-fifth-moon-hubble-discovery.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The satellites' orbits are circular (eccentricity < 0.006) and coplanar with Pluto's equator (inclination < 1°),<ref name="Buie2012">{{cite journal |journal=The Astronomical Journal |last1=Buie |first1=M. |last2=Tholen |first2=D. |last3=Grundy |first3=W. |title=The Orbit of Charon is Circular |year=2012 |volume=144 |issue=1 |pages=15 |doi=10.1088/0004-6256/144/1/15 |bibcode=2012AJ....144...15B|s2cid=15009477 |url=http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bfb8/1eb1887c28df5f5348a491cff7d4870e8c77.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200412141438/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bfb8/1eb1887c28df5f5348a491cff7d4870e8c77.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=April 12, 2020}}</ref><ref name="ShowalterHamilton2015" /> and therefore tilted approximately 120° relative to Pluto's orbit. The Plutonian system is highly compact: the five known satellites orbit within the inner 3% of the region where ]s would be stable.<ref name="Sternetal 2005" /> | |||