| Revision as of 16:06, 22 March 2017 view sourceSoupforone (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users41,755 edits babelmandeb to guardaful per leo africanus← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:06, 1 January 2025 view source Replayerr (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,763 edits →MilitaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1415–1577 Muslim sultanate in the Horn of Africa}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Adal (disambiguation){{!}}Adal}} | |||

| {{about|the sultanate in the Horn of Africa|the historic region|Adal (historical region)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| |native_name = | |||

| {{Over-quotation|many=y|date=April 2024}} | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Sultanate of Adal | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| |common_name = Adal | |||

| | native_name = {{native name|ar|سلطنة عدل|rtl=yes}} | |||

| |continent = Africa | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Sultanate of Adal | |||

| |region = Horn of Africa | |||

| | |

| common_name = Adal | ||

| |era = ] | | era = ] | ||

| |year_start = 1415 | | year_start = 1415 | ||

| |year_end = 1577 | | year_end = 1577 | ||

| |life_span = 1415–1577 | | life_span = 1415–1577 | ||

| |event1 = |

| event1 = ] returns from exile in ] | ||

| |date_event1 = |

| date_event1 = 1415 | ||

| |event2 = |

| event2 = War with ] | ||

| |date_event2 = |

| date_event2 = 1415–1429 | ||

| |event3 = Succession Crisis | | event3 = Succession Crisis | ||

| |date_event3 = 1518–1526 | | date_event3 = 1518–1526 | ||

| |event4 = |

| event4 = ] | ||

| |date_event4 = |

| date_event4 = 1529–1543 | ||

| | |

| p1 = Sultanate of Ifat | ||

| | |

| s1 = Imamate of Aussa | ||

| | |

| image_flag = Flag of Adal Sultanate.svg | ||

| | flag_type = The combined three banners used by Ahmad al-Ghazi's forces | |||

| |date_pre = | |||

| | |

| image_map = Map of the Adal Sultanate (1540).svg | ||

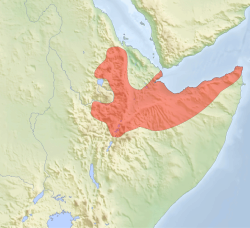

| | image_map_caption = The Adal Sultanate in {{circa|1540}} | |||

| |flag_p1 = | |||

| | |

| capital = *] (1415–1520) | ||

| *]<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dtYWAAAAQAAJ|last=Telles|title=The Travels of the Jesuits in Ethiopia|first=Balthazar|year=1710|publisher=J. Knapton |edition=1st|quote=It might perhaps be to called from Abaxa, the Capital City of the Kingdom of Adel.}}</ref> (1500s ~) | |||

| |flag_s1 = Flag of the Ottoman Empire.svg | |||

| *] (1520–1577) | |||

| |s2 = Sultanate of Harar | |||

| *] (1577) | |||

| |flag_s2 = | |||

| | official_languages = ] | |||

| | | |||

| | common_languages = {{unbulleted list|]|]}} | |||

| |image_flag = Flag of Adal.png | |||

| {{unbulleted list|]|]}} | |||

| |image_flag_size = 200px | |||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| |flag = | |||

| | leader1 = ] | |||

| |flag_type = combination of three banners used by Ahmad al-Ghazi<ref>"the king of Zeila ascended a hill with several horse and some foot to examine us: he halted on the top with three hundred horse and three large banners, two white with red moons, and one red with a white moon, which always accompanied him, and which he was recognized." Richard Stephen Whiteway, ''The Portuguese expedition to Abyssinia in 1541-1543 as Narrated by Castanhoso'', Kraus Reprint, 1967, p. 41 | |||

| | leader2 = ] | |||

| </ref> | |||

| | |

| year_leader1 = 1415–1423 (first) | ||

| | year_leader2 = 1577 (last) | |||

| |image_map = <!-- located between Bab el-Mandeb and Guardafui per Leo Africanus (1526) --> | |||

| | |

| title_leader = ] | ||

| | |

| religion = {{Plainlist| | ||

| * ] (]) | |||

| |national_anthem = | |||

| * ]: ] | |||

| |capital = ] <small>(original capital, as Emirate under ] from 1415-1420)</small><ref name="Lewispd"/> <br/>] <small>(new capital, as Sultanate from 1420-1520)</small><ref name="Lewispd"/> <br /> ] <small>(1520-1577)</small><ref name="Lewispd"/> ] <small>(1577-1577</small><ref>{{cite book|last1=Abir|first1=Mordechai|title=Ethiopia and the Red Sea|publisher=Routledge|page=139|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7fArBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA139&dq=adal+sultanate+aussa&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=adal%20sultanate%20aussa&f=false|accessdate=19 January 2016}}</ref>| | |||

| * ]: ]}} | |||

| |common_languages = ], ], ], ], ]<!-- Per template, parameter is reserved for "major language(s)" --> | |||

| | currency = ]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zekaria |first=Ahmed |date=1991 |title=Harari Coins: A Preliminary Survey |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41965992 |journal=Journal of Ethiopian Studies |volume=24 |pages=24 |jstor=41965992 |issn=0304-2243 |access-date=2024-01-15 |archive-date=2022-12-31 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221231143951/https://www.jstor.org/stable/41965992 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |government_type = ] | |||

| | |

| today = {{unbulleted list|]|]|]|]}} | ||

| |stat_year1 = | |||

| |stat_pop1 = | |||

| |stat_area4 = | |||

| |population_density3 = | |||

| |state religion = ] | |||

| |currency = | |||

| |today = Horn of Africa | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Adal Sultanate''', also known as the '''Adal Empire''' or '''Bar Saʿad dīn''' (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate'', ''Adal Sultanate'') ({{Langx|ar|سلطنة عدل}}), was a medieval ] ] ] which was located in the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ta'a |first1=Tesema |title="Bribing the Land": An Appraisal of the Farming Systems of the Maccaa Oromo in Wallagga |journal=Northeast African Studies |year=2002 |volume=9 |issue=3 |publisher=Michigan State University Press |page=99 |doi=10.1353/nas.2007.0016 |jstor=41931282 |s2cid=201750719 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41931282 |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2021-05-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210520123343/https://www.jstor.org/stable/41931282 |url-status=live }}</ref> It was founded by ] on the ] plateau in ] after the fall of the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ahmed |first1=Hussein |title=Reflections on Historical and Contemporary Islam in Ethiopia and Somalia: A Comparative and Contrastive Overview |journal=Journal of Ethiopian Studies |year=2007 |volume=40 |issue=1/2 |publisher=Institute of Ethiopian Studies |page=264 |jstor=41988230 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41988230 |access-date=2023-03-22 |archive-date=2023-02-01 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230201151444/https://www.jstor.org/stable/41988230 |url-status=live }}</ref> The kingdom flourished {{Circa|1415}} to 1577.<ref name="The Cross and the River: Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Nile">{{harvnb|Elrich|2001|p=36}}.</ref> At its height, the polity under Sultan ] controlled the territory stretching from ] in ] to the port city of ] in ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pradines |first1=Stéphane |title=Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa From Timbuktu to Zanzibar |date=7 November 2022 |publisher=BRILL |page=127 |isbn=9789004472617 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f1ebEAAAQBAJ&dq=suakin+adal&pg=PA127 |access-date=7 July 2023 |archive-date=22 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133227/https://books.google.com/books?id=f1ebEAAAQBAJ&dq=suakin+adal&pg=PA127#v=onepage&q=suakin%20adal&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Braukamper |first1=Ulrich |title=Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia |year=2002 |publisher=Lit |page=33 |isbn=9783825856717 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HGnyk8Pg9NgC&dq=concluded+that+adal+at+the+time+of+its+greatest+expansion+comprised&pg=PA33 |access-date=2023-07-07 |archive-date=2024-05-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133115/https://books.google.com/books?id=HGnyk8Pg9NgC&dq=concluded+that+adal+at+the+time+of+its+greatest+expansion+comprised&pg=PA33#v=onepage&q=concluded%20that%20adal%20at%20the%20time%20of%20its%20greatest%20expansion%20comprised&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Owens |first1=Travis |title=BELEAGUERED MUSLIM FORTRESSES AND ETHIOPIAN IMPERIAL EXPANSION FROM THE 13TH TO THE 16TH CENTURY |publisher=NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL |page=23 |url=https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a483490.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201112020204/https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a483490.pdf|url-status=live|archive-date=November 12, 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Pouwels |first1=Randall |title=The History of Islam in Africa |date=31 March 2000 |publisher=Ohio University Press |page=229 |isbn=9780821444610 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J1Ipt5A9mLMC&q=Sawakin+adal&pg=PA229 |access-date=15 October 2020 |archive-date=18 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230918091324/https://books.google.com/books?id=J1Ipt5A9mLMC&q=Sawakin+adal&pg=PA229 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Leo |first1=Africanus |url=http://archive.org/details/historyanddescr03porygoog |title=The history and description of Africa |last2=Pory |first2=John |last3=Brown |first3=Robert |date=1896 |publisher=London, Printed for the Hakluyt society |others=Harvard University |pages=51–53}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Hassan |first=Mohamed |title=The Oromo of Ethiopia: A History, 1570-1860. |location= |pages=35}}</ref> The Adal Empire maintained a robust commercial and political relationship with the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Salvadore|first1=Matteo|title=The African Prester John and the Birth of Ethiopian-European Relations, 1402–1555|date=2016|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1317045465|page=158|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BQ5qDAAAQBAJ|access-date=18 March 2018}}</ref> Sultanate of Adal was alternatively known as the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Brill |first1=E. J. |title=E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. A - Bābā Beg · Volume 1 |year=1993 |publisher=Brill |page=126 |isbn=9789004097872 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GEl6N2tQeawC&dq=adal+or+zaila&pg=PA126 |access-date=2023-07-07 |archive-date=2024-05-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133217/https://books.google.com/books?id=GEl6N2tQeawC&dq=adal+or+zaila&pg=PA126#v=onepage&q=adal%20or%20zaila&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| The '''Adal Sultanate''' or '''Kingdom of Adal''' (alt. spelling '''Adel Sultanate''') was a multi-ethnic medieval ] state located in the ]. It was founded by ] after the fall of | |||

| Adal is believed to be an abbreviation of ].<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Gifford| first1=William| title=Forster on Arabia| journal=The Quarterly Review| date=1844| volume=74| page=338| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CE1OAQAAMAAJ&q=adal+havilah&pg=PA338}}</ref> Eidal or ] Abdal, was the Emir of ] in the eleventh century which the lowlands outside the city of Harar is named.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mohammed |first1=Duri |title=The Mugads of Harar |date=4 December 1955 |publisher=University College of Addis Abeba Ethnological Bulletin |page=1 |url=https://everythingharar.com/images/pdf/publication/Mugads%20Of%20Harar-Mohammed.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210710195739/https://everythingharar.com/images/pdf/publication/Mugads%20Of%20Harar-Mohammed.pdf |access-date=10 July 2021|archive-date=2021-07-10 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book| last1=Wehib| first1=Ahmed| title=History of Harar and the Hararis| date=October 2015| publisher=Harari People Regional State Culture, Heritage And Tourism Bureau| page=105| url=http://www.everythingharar.com/files/History_of_Harar_and_Harari-HNL.pdf| access-date=26 July 2017| archive-date=21 March 2020| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200321065415/http://www.everythingharar.com/files/History_of_Harar_and_Harari-HNL.pdf| url-status=live}}</ref> In the thirteenth century, the Arab writer ] refers to the city of ],<ref name="Lewispd">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|title=A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa|year=1999|publisher=James Currey Publishers|isbn=0852552807|pages=17|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eK6SBJIckIsC&pg=PA17|access-date=2015-10-14|archive-date=2023-01-23|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123104930/https://books.google.com/books?id=eK6SBJIckIsC&pg=PA17|url-status=live}}</ref> by its Somali name "Awdal" ({{langx|so|"Awdal"}}).<ref>{{harvnb|Tamrat|1977|p=139}}.</ref> The modern ] region of ], which was part of the Adal Sultanate, bears the kingdom's name. | |||

| ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Briggs|first1=Phillip|title=Somaliland|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC&pg=PA152&dq=sabr+addin+founded+adal&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=sabr%20addin%20founded%20adal&f=false|accessdate=25 April 2016}}</ref> The kingdom flourished from around 1415 to 1577.<ref name="The Cross and the River: Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Nile">{{cite journal | last =elrik | first =Haggai | title =The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600 | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =36 | publisher =Lynne Rienner | location = USA | year =2007 | url =https://books.google.com/books?id=mhCN2qo43jkC&pg=PA36 | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> The sultanate and state was established by the inhabitants of the Harar Plateau.<ref>{{cite journal | last =Fage | first =J.D | coauthors = | title = The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600 | journal =ISIM Review | volume = | issue =Spring 2005 | pages =169 | publisher = Cambridge University Press | location =UK | year =2010 | url =https://books.google.com/books?id=Qwg8GV6aibkC&pg=PA146#v=onepage&q&f=false| doi = | accessdate =2009-04-10}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Shinn">{{cite book|author=David Hamilton Shinn & Thomas P. Ofcansky|title=Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia|year=2004|publisher=Scarecrow Press|isbn=0810849100|pages=5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ep7__RWqq4IC&pg=PA5 }}</ref> At its height, the polity controlled large parts of ] (including the self-declared state of ]), ], ] and ]. | |||

| Locally the empire was known to the Muslims as ''Bar Sa'ad ad-din'' meaning "The country of Sa'ad ad-din" in reference to the Sultan ], who was killed in ] while fighting the Ethiopian Emperor ].<ref>The "Futuh al-Habasa" : the writing of history, war and society in the "Bar Sa'ad ad-din" (Ethiopia, 16th century)</ref><ref>Burton, ''First Footsteps in East Africa'', 1856; edited with additional material by Gordon Waterfield (New York: Praeger, 1966), p. 75.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Pankhurst |first=Richard |year=1982 |title=History Of Ethiopian Towns |page=57 |publisher=Steiner |isbn=9783515032049 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| The origins of the name Adal are obscure. But al-'Umari mentions | |||

| it with Shoa and Zeila as being an integral part of the Muslim confederation | |||

| led by Ifat.<ref>Cambridge History of Africa Volume 3 From c.1050 to c. 1600, Cambridge University Press, 2008, page 149</ref> | |||

| ==History == | |||

| In the thirteenth century, Arab writer, Al Dimashqi, refers to the Adal Sultanate's capital, ], by its Somali name "Awdal" ({{lang-so| "Awdal"}}).<ref>{{cite journal | last =Fage | first =J.D | coauthors = | title = The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600 | journal =ISIM Review | volume = | issue =Spring 2005 | pages =139 | publisher = Cambridge University Press | location =UK | year =2010}}</ref> | |||

| ===Early history=== | |||

| The modern ] region, which was part of the Adal Sultanate, bears the kingdom's name. | |||

| {{main|Adal (historical region)}} | |||

| {{anchor|Kingdom of Adal}}] (also ''Awdal'', ''Adl'', or ''Adel'')<ref name="Somalia">{{cite book |last1=Mukhtar |first1=Mohamed Haji |title=Historical dictionary of Somalia |date=2003 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |location=Lanham, Md. |isbn=0810843447 |pages=44 |edition=New |chapter=Awdal |series=African Historical Dictionary Series|volume=87}}</ref> was situated east of the province of ] and was a general term for a region of lowlands inhabited by Muslims. It was used ambiguously in the medieval era to indicate the Muslim inhabited low land portion east of the ]. Including north of the ] towards ] as well as the territory between ] and ] on the coast of ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Josef |first1=Josef |title=Medieval Islamic Civilization |date=12 January 2018 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=9781351668224 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QepGDwAAQBAJ&dq=but+some+returned+and+ruled+further+east+of+yifat&pg=PT133 |access-date=2 April 2023 |archive-date=2 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230402042337/https://books.google.com/books?id=QepGDwAAQBAJ&dq=but+some+returned+and+ruled+further+east+of+yifat&pg=PT133 |url-status=live }}</ref>{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=52}}<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WU92d6sB8JAC&q=%22and+the+lowlands+between+shoa+province+and+the+port+of+zeila+in+present-day+somaliland%22&pg=PA20|title=Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia|last1=Shinn|first1=David H.|last2=Ofcansky|first2=Thomas P.|date=2013-04-11|publisher=Scarecrow Press|isbn=9780810874572|language=en|access-date=2020-10-15|archive-date=2024-05-22|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133241/https://books.google.com/books?id=WU92d6sB8JAC&q=%22and+the+lowlands+between+shoa+province+and+the+port+of+zeila+in+present-day+somaliland%22&pg=PA20#v=snippet&q=%22and%20the%20lowlands%20between%20shoa%20province%20and%20the%20port%20of%20zeila%20in%20present-day%20somaliland%22&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref> According to Ewald Wagner, Adal region was historically the area stretching from Zeila to ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wagner |first1=Ewald |title=Legende und Geschichte: der Fath Madinat Hara von Yahya Nasrallah |publisher=Verlag}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Trimingham |first1=J.Spencer |title=Islam in Ethiopia |date=13 September 2013 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=9781136970290 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Kd3bAAAAQBAJ&dq=adal+bordered+on+shoa&pg=PT162 |access-date=2 April 2023 |archive-date=2 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230402042335/https://books.google.com/books?id=Kd3bAAAAQBAJ&dq=adal+bordered+on+shoa&pg=PT162 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1288, the region of Adal was conquered by the ]. Despite being incorporated into the Ifat Sultanate, Adal managed to maintain a source of independence under ] rule, alongside the provinces of ], ], Sawans, ], and ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dR5yCmUejWEC&dq=hargaya+ethiopia&pg=PA184|title=Muslim society's in Africa|isbn=9780253007971|last1=Loimeier|first1=Roman|date=5 June 2013|publisher=Indiana University Press|access-date=22 March 2023|archive-date=15 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230315220617/https://books.google.com/books?id=dR5yCmUejWEC&dq=hargaya+ethiopia&pg=PA184|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1332, Adal was invaded by the Ethiopian Emperor ]. His soldiers were said to have ravaged the province.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Pankhurst |first=Richard |year=1982 |title=History Of Ethiopian Towns |page=63 |publisher=Steiner |isbn=9783515032049 }}</ref><ref name="Houtsma">{{cite book |last=Houtsma |first=M. Th |title=E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 |year=1987 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=9004082654 |pages=125–126 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zJU3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA125 |access-date=2015-10-14 |archive-date=2023-01-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123104929/https://books.google.com/books?id=zJU3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA125 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Somaliland">{{cite journal | last =mbali | title =Somaliland | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | pages =217–229 | publisher =mbali | location =London, UK | year =2010 | url =http://www.mbali.info/doc328.htm | doi =10.1017/S0020743800063145 | s2cid =154765577 | access-date =2012-04-27 | url-status =dead | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20120423062326/http://www.mbali.info/doc328.htm | archive-date =2012-04-23 }}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| In the fourteenth century ] transferred Ifat's capital to the ] plateau thus he is regarded by some to be the true founder of the Adal Sultanate.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Cambridge History of Africa |year=1975 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=150 |isbn=9780521209816 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&dq=haqedin%27s+transfer+of+his+political+centre+from+Ifat+to+the+Harar+area&pg=PA150 |access-date=2023-03-22 |archive-date=2023-03-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230322220639/https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&dq=haqedin%27s+transfer+of+his+political+centre+from+Ifat+to+the+Harar+area&pg=PA150 |url-status=live }}</ref> In the late 14th century, the Ethiopian Emperor ] collected a large army, branded the Muslims of the surrounding area "enemies of the Lord", and invaded Adal.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=J.D. |title=The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050 |year=1975 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=154 |isbn=9780521209816 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&dq=dawit+led+a+series+of+energetic+campaigns+into+the+very+heart+of+the+harar+plateau&pg=PA154 |access-date=2023-03-22 |archive-date=2023-03-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230316181744/https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&dq=dawit%20led%20a%20series%20of%20energetic%20campaigns%20into%20the%20very%20heart%20of%20the%20harar%20plateau&pg=PA154 |url-status=live }}</ref> After much war, Adal's troops were defeated in 1403 or 1410<ref>] gives the former date, while the Walashma chronicle gives the latter.</ref> (under Emperor ] or Emperor ], respectively), during which the ] ruler, ], was captured and executed in Zeila, which was sacked.<ref name="Somaliland" /> His children and the remainder of the ] would flee to ] where they would live in exile until 1415.<ref>Pankhurst. ''Ethiopian Borderlands'', pp.57</ref><ref>Budge, ''A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia'', 1928 (Oosterhout, the Netherlands: Anthropological Publications, 1970), p. 302.</ref> According to ] tradition numerous Argobba had fled Ifat and settled around Harar in the ] lowlands during their conflict with Abyssinia in the fifteenth century, a gate was thus named after them called the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=ABUBAKER |first1=ABDULMALIK |title=THE RELEVANCY OF HARARI VALUES IN SELF REGULATION AND AS A MECHANISM OF BEHAVIORAL CONTROL: HISTORICAL ASPECTS |publisher=The University of Alabama |page=44 |url=https://everythingharar.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/RelevanceofhararivaluesAbdumalik.pdf |access-date=2023-06-06 |archive-date=2024-05-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133027/https://everythingharar.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/RelevanceofhararivaluesAbdumalik.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Establishment=== | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| According to ], the Adal Sultanate's realm encompassed the geographical area between the Bab el Mandeb and Cape Guardafui. It was thus flanked to the south by the ] and to the west by the ].<ref name="Leo">{{cite book|last1=Africanus|first1=Leo|title=The History and Description of Africa|date=1526|publisher=Hakluyt Society|pages=51-54|url=https://archive.org/stream/historyanddescr03porygoog#page/n180/mode/2up|accessdate=2 January 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ===Rise of the Sultanate=== | |||

| ] was introduced to the Horn region early on from the ], shortly after the ]. ]'s two-] ] dates to about the 7th century, and is the oldest ] in the city.<ref name="Btgpb">{{cite book|last=Briggs|first=Phillip|title=Somaliland|year=2012|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=1841623717|page=7|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC}}</ref> In the late 9th century, ] wrote that ]s were living along the northern Somali seaboard.<ref name="Encyamer">{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25|year=1965|publisher=Americana Corporation|pages=255|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OP5LAAAAMAAJ}}</ref> He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city.<ref name="Encyamer"/><ref name="Lewispohoa">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I.M.|title=Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho|year=1955|publisher=International African Institute|pages=140|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Cd0mAQAAMAAJ}}</ref> The polity was governed by local dynasties established by the Adelites.<ref name="Leo"/> Adal's history from this founding period forth would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighbouring ].<ref name="Lewispohoa"/> | |||

| In 1415, ], the eldest son of ], would return to Adal from his exile in Arabia to restore his father's throne.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mordechai |first1=Abir |title=Ethiopia And The Red Sea |publisher=Hebrew University of Jerusalem |pages=26–27 |url=https://zelalemkibret.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/ethiopia-and-the-red-sea-mordichi-abir.pdf |access-date=2023-03-22 |archive-date=2021-05-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210517214033/https://zelalemkibret.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/ethiopia-and-the-red-sea-mordichi-abir.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> He would proclaim himself "king of Adal" after his return from Yemen to the ] plateau and established his new capital at ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wagner |first1=Ewald |title=The Genealogy of the later Walashma' Sultans of Adal and Harar |journal=Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft |year=1991 |volume=141 |issue=2 |pages=376–386 |publisher=Harrassowitz Verlag |jstor=43378336 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43378336 |access-date=2021-03-12 |archive-date=2021-05-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210506032705/https://www.jstor.org/stable/43378336 |url-status=live }}</ref> Sabr ad-Din III and his brothers would defeat an army of 20,000 men led by an unnamed commander hoping to restore the "lost Amhara rule". The victorious king then returned to his capital, but gave the order to his many followers to continue and extend the war against the Christians.<ref name="Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: O-X - Google Books">{{cite book |last1=Bausi |first1=Alessandro |title=Tewodros |year=2010 |publisher=Encyclopedia Aethiopica |page=930 |isbn=9783447062466 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t8VHAQAAIAAJ&q=T%C3%A9wodros+adal |access-date=2023-03-18 |archive-date=2023-03-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230322221253/https://books.google.com/books?id=t8VHAQAAIAAJ&q=T%C3%A9wodros+adal |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Cairn Info p. 117">{{cite journal |last1=Chekroun |first1=Amelie |title=Le sultan walasmaʿ Saʿd al-Dīn et ses fils |journal=Médiévales |date=2020 |volume=79 |issue=2 |pages=117–136 |publisher=Cairn Info |doi=10.4000/medievales.11082 |url=https://www.cairn.info/revue-medievales-2020-2-page-117.htm |access-date=2022-07-22 |archive-date=2022-08-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220804080312/https://www.cairn.info/revue-medievales-2020-2-page-117.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Royal Names in Medieval Ethiopia and their Symbolism">{{cite journal |last1=Gusarova |first1=Ekaterina |title=Royal Names in Medieval Ethiopia and their Symbolism |journal=Scrinium |year=2021 |volume=17 |pages=349–355 |publisher=BRILL |doi=10.1163/18177565-BJA10026 |s2cid=240884465 |url=https://brill.com/view/journals/scri/17/1/article-p349_20.xml |doi-access=free |access-date=2022-07-22 |archive-date=2022-07-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220705004813/https://brill.com/view/journals/scri/17/1/article-p349_20.xml |url-status=live }}</ref> The Emperor of Ethiopia ] was soon killed by the Adal Sultanate upon the return of Sa'ad ad-Din's heirs to the Horn of Africa.<ref name="Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: O-X - Google Books" /><ref name="Cairn Info p. 117" /><ref name="Royal Names in Medieval Ethiopia and their Symbolism" /> ] died a natural death and was succeeded by his brother ] who invaded the capital and royal seat of the Solomonic Empire and drove Emperor ] to Yedaya where according to ], Sultan Mansur destroyed a Solomonic army and killed the Emperor. He then advanced to the mountains of Mokha, where he encountered a 30,000 strong Solomonic army. The Adalite soldiers surrounded their enemies and for two months besieged the trapped Solomonic soldiers until a truce was declared in Mansur's favour. During this period, Adal emerged as a centre of Muslim resistance against the expanding Christian Abyssinian kingdom.<ref name="Lewispd" /> Adal would thereafter govern all of the territory formerly ruled by the Ifat Sultanate,<ref>{{cite book|last1=Briggs|first1=Phillip|title=Somaliland|year=2012|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=9781841623719|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC&q=sabr+addin+founded+adal&pg=PA152|access-date=25 April 2016|archive-date=22 May 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133126/https://books.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC&q=sabr+addin+founded+adal&pg=PA152#v=onepage&q=sabr%20addin%20founded%20adal&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5qlXatHRJtMC&q=Ifat+sultanate+ruled+present+day+north+western+somalia&pg=PA358|title=Nation Shapes: The Story Behind the World's Borders: The Story behind the World's Borders|last=Shelley|first=Fred M.|date=2013-04-23|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=9781610691062|language=en|access-date=2020-10-15|archive-date=2024-05-22|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522133149/https://books.google.com/books?id=5qlXatHRJtMC&q=Ifat+sultanate+ruled+present+day+north+western+somalia&pg=PA358|url-status=live}}</ref> as well as the land further east all the way to Cape Guardafui, according to Leo Africanus.<ref name="Leo">{{cite book | last1=Africanus| first1=Leo| title=The History and Description of Africa| date=1526| publisher=Hakluyt Society| pages=51–54| url=https://archive.org/stream/historyanddescr03porygoog#page/n180/mode/2up}}</ref> | |||

| Adal is mentioned by name for the first time in the 14th century, in the context of the battles between the Muslims of the northern Somali and Afar seaboard and the Abyssinian King ]'s ] troops.<ref name="Houtsma">{{cite book|last=Houtsma|first=M. Th|title=E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936|year=1987|publisher=BRILL|isbn=9004082654|pages=125–126|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zJU3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA125 }}</ref> Adal originally had its capital in the port city of ], situated in the northwestern ] region. The polity at the time was an ]ate in the larger ] ruled by the ].<ref name="Lewispd">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|title=A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa|year=1999|publisher=James Currey Publishers|isbn=0852552807|pages=17|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eK6SBJIckIsC&pg=PA17 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Rise and fall=== | |||

| ] and his men. From ''Le Livre des Merveilles'', 15th century.]] | ] and his men. From ''Le Livre des Merveilles'', 15th century.]] | ||

| {{History_of_Ethiopia}} | |||

| In 1332, the King of Adal was slain in a military campaign aimed at halting Amda Seyon's march toward Zeila.<ref name="Houtsma"/> When the last Sultan of Ifat, ], was also killed by ] at the port city of Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to ], before later returning in 1415.<ref name ="Somaliland">{{cite journal | last =mbali| title =Somaliland | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =mbali | location = London, UK | year =2010 | url =http://www.mbali.info/doc328.htm | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of ], where ], the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new Adal administration after his return from Yemen.<ref name="Lewispd"/><ref name="Bradt">{{cite book|last=Briggs|first=Philip|title=Bradt Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia|year=2012|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=1841623717|pages=10|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC&pg=PA10 }}</ref> During this period, Adal emerged as a center of Muslim resistance against the expanding Christian Abyssinian kingdom.<ref name="Lewispd"/> | |||

| Later on in the campaign, the Adalites were struck by a catastrophe when Sultan Mansur and his brother Muhammad were captured in battle by the Solomonids. Mansur was immediately succeeded by the youngest brother of the family ]. Sultan Jamal reorganized the army into a formidable force and defeated the Solomonic armies at ], Yedeya and Jazja. Emperor Yeshaq I responded by gathering a large army and invaded the cities of Yedeya and Jazja, but was repulsed by the soldiers of Jamal. Following this success, Jamal organized another successful attack against the Solomonic forces and inflicted heavy casualties in what was reportedly the largest Adalite army ever fielded. As a result, Yeshaq and his men fled to the ] region over the next five months, while Jamal ad Din's forces pursued them and looted much gold on the way, although no engagement ensued.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=58}} | |||

| After 1468, a new breed of rulers emerged on the Adal political scene. The dissidents opposed Walashma rule owing to a treaty that Sultan ] had signed with Emperor ], wherein Badlay agreed to submit yearly tribute. This was done to achieve peace in the region, though tribute was never sent. Adal's ]s, who administered the provinces, interpreted the agreement as a betrayal of their independence and a retreat from the polity's longstanding policy of resistance to Abyssinian incursions. The main leader of this opposition was the Emir of Zeila, the Sultanate's richest province. As such, he was expected to pay the highest share of the annual tribute to be given to the Abyssinian Emperor.<ref name ="Specific Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =zum | title =Event Documentation | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =AGCEEP | location = USA | year =2007 | url =http://agceep.net/eventdoc/AGCEEP_Specific_Ethiopia.eue.htm | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> Emir Laday Usman subsequently marched to Dakkar and seized power in 1471. However, Usman did not dismiss the Sultan from office, but instead gave him a ceremonial position while retaining the real power for himself. Adal now came under the leadership of a powerful Emir who governed from the palace of a nominal Sultan.<ref name ="Islam in Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =Trimingham | first =John | title =Islam in Ethiopia | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =167 | publisher =Oxford University Press | location = Oxford | year =2007 | url =https://books.google.com/books?id=B4NHAQAAIAAJ&q=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471&dq=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rn65T-bpF6TG6AHghbGDCw&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA |accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> | |||

| After returning home, Jamal sent his brother Ahmad with the Christian battle-expert Harb Jaush to successfully attack the province of Dawaro. Despite his losses, Emperor Yeshaq was still able to continue field armies against Jamal. Sultan Jamal continued to advance further into the Abyssinian heartland. However, Jamal on hearing of Yeshaq's plan to send several large armies to attack three different areas of Adal (including the capital), returned to Adal, where he fought the Solomonic forces at Harjai and, according to al-Maqrizi, this is where the Emperor Yeshaq died in battle. The young Sultan Jamal ad-Din II at the end of his reign had outperformed his brothers and forefathers in the war arena and became the most successful ruler of Adal to date. Within a few years, however, Jamal was assassinated by either disloyal friends or cousins around 1432 or 1433, and was succeeded by his brother ]. Sultan Badlay continued the campaigns of his younger brother and began several successful expeditions against the Christian empire. He reconquered ] and began preparations of a major Adalite offensive into the ]. He successfully collected funding from surrounding Muslim kingdoms as far away as the ].<ref>Richard Gray, ''The Cambridge history of Africa'', Volume 4. p. 155.</ref> However, this ambitious campaign ended in disaster when Emperor ] defeated Sultan Badlay at the ] and pursued the retreating Adalites all the way to the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Cerulli |first1=Enrico |title=Islam: Yesterday and Today translated by Emran Waber |publisher=Istituto Per L'Oriente |page=140 |url=https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2021-08-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210822194826/https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Adalite armies under the leadership of rulers such as ], ], ], ] and ] ] subsequently continued the struggle against Abyssinian expansionism. | |||

| Following the defeat and death of ] at the ], the next Sultan of Adal, ], submitted to Emperor ] and started paying annual tribute to the ] with which he secure peace.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29226/1/10731321.pdf|title=The Oromo of Ethiopia 1500-1800|page=25|access-date=2021-09-07|archive-date=2020-02-13|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200213003344/https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29226/1/10731321.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> Adal's ]s, who administered the provinces, interpreted the agreement as a betrayal of their independence and a retreat from the polity's long-standing policy of resistance to Abyssinian incursions. Emir Laday Usman of ] subsequently marched to ] and seized power in 1471. However, Usman did not dismiss the Sultan from office, but instead gave him a ceremonial position while retaining the real power for himself. Adal now came under the leadership of a powerful Emir who governed from the palace of a nominal Sultan.<ref name ="Islam in Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =Trimingham | first =John | title =Islam in Ethiopia | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | pages =167 | publisher =Oxford University Press | location =Oxford | year =2007 | url =https://books.google.com/books?id=B4NHAQAAIAAJ&q=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471 | access-date =2012-04-27 | archive-date =2024-05-22 | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20240522134620/https://books.google.com/books?id=B4NHAQAAIAAJ&q=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471 | url-status =live }}</ref> Usman would route emperor Baeda Maryam's troops in battle.<ref>{{cite book |last1=S.C. |first1=Munro-Hay |title=Ethiopia, the unknown land : a cultural and historical guide |date=2002 |publisher=I.B. Tauris |page=25 |isbn=978-1-86064-744-4 |url=https://archive.org/details/ethiopiaunknownl0000munr/page/24/mode/2up?q=asman}}</ref> Historian ] states Adal Sultans had lost control of the state to Harar's aristocracy.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hassan |first1=Mohammed |title=The Oromo of Ethiopia, 1500-1850 |publisher=University of London |pages=24–25 |url=https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29226/1/10731321.pdf |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2020-02-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200213003344/https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29226/1/10731321.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name ="Specific Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =zum | title =Event Documentation | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | pages =217–229 | publisher =AGCEEP | location =USA | year =2007 | url =http://agceep.net/eventdoc/AGCEEP_Specific_Ethiopia.eue.htm | doi =10.1017/S0020743800063145 | s2cid =154765577 | access-date =2012-04-27 | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20110913142126/http://www.agceep.net/eventdoc/AGCEEP_Specific_Ethiopia.eue.htm | archive-date =2011-09-13 | url-status =dead }}</ref> | |||

| ] armed with a musket and a cannon]] | |||

| Emperor ] and Sultan ] tried to remain at peace, but their efforts were nullified by the raids which Emir ] constantly made into Christian territory. ] who was determined to eliminate this threat, organized a large army and led it against the Emir, although the Emperor was victorious he was eventually killed in battle against the Adalites. Emperor ] (Lebna Dengel) would soon succeed the throne, ] having recovered from his defeat renewed raids against the frontier provinces. He was stimulated by emissaries from Arabia who proclaimed the jihad (holy war), presented him with a green standard and brought in arms and trained men from Yemen. In 1516, Emir Mahfuz would then launch an invasion of ], Lebna Dengel was prepared and organized a successful ambush, the Adalites were defeated and Mahfuz was killed in battle. Lebna Dengel then moved into Adal where he sacked the city of ]. Around the same time a Portuguese fleet surprised ] whilst its garrison was away with Mahfuz, the Portuguese then burnt down the port city.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Huntingford |first1=G.W.B |title=The historical geography of Ethiopia from the first century AD to 1704 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=105}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Trimmingham |first1=John Spencer |title=Islam in Ethiopia |date=1952 |page=83 |publisher=Frank Cass & Company |isbn=9780714617312 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |access-date=2023-05-12 |archive-date=2023-04-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405063221/https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| After the victory of Lebna Dengel, the internal weaknesses of the Adal Sultanate soon revealed themselves. The older generation of the Muslims headed by the ], indifferent to religion and ready to come to terms with ], were staunchly opposed by the ] and ] religious aristocracy led by fanatic warlike emirs.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hassan |first1=Mohammed |title=Oromo of Ethiopia |publisher=University of London |pages=24–25 |url=https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29226/1/10731321.pdf |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2020-02-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200213003344/https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/29226/1/10731321.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The Sultan ] was assassinated in 1518 and Adal was torn apart by intestinal struggles in which five sultans succeeded each other in two years. But at last, a matured and powerful leader called ] ] assumed power and brought order out of chaos. However, Sultan ], who had transferred the capital from ] to ] in 1520, profiting off the prestige that the hereditary monarchy still held, recruited bands of Somali nomads, ambushed ] at Zeila and killed him in 1525.<ref name="Lewispd"/> Many people went to join the force of a young rebel named ], who claimed revenge for Garad Abogn. Ahmad did not immediately attempt conclusions with Sultan Abu Bakr, but retired to ] to build up his strength. ] would eventually kill Sultan Abu Bakr in battle, and replaced him with Abu Bakr's younger brother ] as his puppet. Once in complete control, he then could then turn to the task he felt himself was divinely appoint to undertake, the conquest of Abyssinia. Fervor for the jihad had not yet overcome the forces inherent in nomadic life, Ahmad had to undertake several campaigns to restore order in the Somali territory which would constitute his manpower reserve. He then organized a heterogenous mass of tribes into a powerful army, inflamed by the fanatical zeal of jihad.<ref>{{harvnb|Tamrat|1977|pp=168–170}}.</ref><ref>Jeremy Black, ''Cambridge Illustrated Atlas, Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution'', 1492–1792, (Cambridge University Press: 1996), p. 9.</ref><ref name="Islam in Ethiopia - John Spencer Trimingham - Google Books">{{cite book |last1=Trimmingham |first1=John Spencer |title=Islam in Ethiopia |date=1952 |page=84 |publisher=Frank Cass & Company |isbn=9780714617312 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |access-date=2023-05-12 |archive-date=2023-04-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405063221/https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Conquest of Abyssinia=== | |||

| {{main|Ethiopian–Adal war}} | |||

| ] and ]'s deaths.]] | |||

| According to sixteenth century Adal writer ], in 1529 Imam ] finally decided to embark on a conquest of Abyssinia, he soon met the Abyssinians at the ] where he would win a decisive victory. But his nomads where unreliable and difficult to control, to Ahmad's frustration some of his ] warriors would disperse back to their homelands after acquiring much plunder. At the same time, he faced opposition from his ] troops who dreaded the potential consequences of the Muslim base relocating to Abyssinia. He then returned to ] to reconstruct his forces and eliminate the tribal allegiances in his army, two years later he was able to organize a definite and permeant occupation of Abyssinia. From then the story of the conquest is a succession of victories, burnings and massacres. In 1531 ] and ] were occupied, ] and ] in 1533. In 1535 Ahmad, in control of the east and center of Abyssinia invaded ] where he encountered fierce resistance and suffered some reserves, but his advance was not stopped, his armies reached the coasts of ] and ] where they made contact with the Muslim ] tribes of the north that had formerly paid tribute to the ]. Emperor ] (Lebna Dengel) became a hunted fugitive, and harried from ] to ] to ], constantly pursued by the Adalites.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Trimmingham |first1=John Spencer |title=Islam in Ethiopia |date=1952 |page=87 |publisher=Frank Cass & Company |isbn=9780714617312 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |access-date=2023-05-12 |archive-date=2023-04-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405063221/https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Cerulli |first1=Enrico |title=Islam Yesterday and Today translated by Emran Waber |pages=376–381 |url=https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2021-08-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210822194826/https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view |url-status=live }}</ref> In this period Adal Sultanate occupied a territory stretching from ] to ] as well as the Abyssinian inlands.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Marcus |first1=Harold |title=A History of Ethiopia |date=22 February 2002 |publisher=University of California Press |page=32 |isbn=9780520925427 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hCpttQcKW7YC&dq=zeila+to+mitsiwa+on+the+coast&pg=PA32 |access-date=7 July 2023 |archive-date=22 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522134729/https://books.google.com/books?id=hCpttQcKW7YC&dq=zeila+to+mitsiwa+on+the+coast&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q=zeila%20to%20mitsiwa%20on%20the%20coast&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The Adalites were passionately interested in converting newly occupied territories. The impression given in the Muslim chronicles is that almost all of the Christian ] had embraced Islam out of expediency. Among them was the governor of ] who wrote to the Imam: | |||

| {{blockquote|I was once a Muslim, the son of a Muslim, but the polytheists captured me and made me a Christian. Yet at heart I remain steadfast in the religion and now I seek the protection of Allah, His prophet, and yourself. If you accept my repentance and do not punish for what I have done I will return to Allah whilst these armies that are under my command I will deceive them so that they will come to you and embrace Islam.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Trimmingham |first1=John Spencer |title=Islam in Ethiopia |date=1952 |page=88 |publisher=Frank Cass & Company |isbn=9780714617312 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |access-date=2023-05-12 |archive-date=2023-04-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405063221/https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| However, in the integral regions of the ], such as ], ] and ], the local population bitterly resisted the Adalite occupation. Some preferred death over denying their faith, among them were two ] chiefs who were brought before the Imam in ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pankhurst |first1=Richard |title=The Ethiopians: A History |date=October 23, 1998 |publisher=Wiley |page=88 |isbn=9780631224938 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8mNnXC_oVmQC |access-date=July 7, 2023 |archive-date=August 21, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230821200927/https://books.google.com/books?id=8mNnXC_oVmQC |url-status=live }}</ref> ] describes the encounter: | |||

| {{blockquote|They captured two Christian chiefs and sent them to the Imam's encampment and presented them before him. He said "What is the matter with you that you haven't become Muslims when the whole country was Islamized?" They replied "We don't want to become Muslims." The Imam said "Our judgment on you is that your heads be cut off." The two Christians replied "Very well!" The Imam was surprised at their reply and ordered them to be executed.<ref name="Islam in Ethiopia - John Spencer Trimingham - Google Books" />}} | |||

| In 1541 a small Portuguese contingent landed in ] and soon all of Tigray declared for the monarchy, the Imam was defeated in several major engagements by the Portuguese and was forced to flee to ] with his heavily demoralized followers. He sent a request to the ] for reinforcements of Turkish, Albanian and Arab musketeers to stabilize his troops. He then took the offensive attacking the Portuguese camp at Wolfa where he killed their commander, ], and 200 of their rank and file. The Imam then dismissed most of his foreign contingent and returned to his headquarters at ]. The surviving Portuguese were able to meet up with ] and his army at ]. The Emperor did not hesitate to take the offensive and won a major victory at the ] when the fate of Abyssinia was decided by the death of the Imam and the flight of his army. The invasion force collapsed like a house of cards and all the Abyssinians who had been cowed by the invaders returned to their former allegiance, the reconquest of Christian territories proceeded without encountering any effective opposition.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Trimmingham |first1=John Spencer |title=Islam in Ethiopia |date=1952 |page=89 |publisher=Frank Cass & Company |isbn=9780714617312 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |access-date=2023-05-12 |archive-date=2023-04-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405063221/https://books.google.com/books?id=XbVmNAAACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Collapse of the sultanate=== | |||

| {{main|Oromo migrations}} | |||

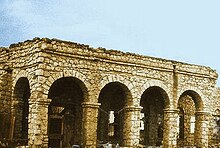

| ] built by ]]] | |||

| After the death of Imam Ahmad, the Adal Sultanate lost most of its territory in Abyssinian lands. In 1550 ] became the Emir of Harar and the de facto ruler of Adal. He then departed on a '']'' (holy war) to the eastern Ethiopian lowlands of ] and ]. This venture was unsuccessful, Nur was defeated and the Abyssinians then advanced into Adalite territory where upon they ravaged the lands and enslaved many of its inhabitants. However, this defeat was not mortal and Adal soon recovered. At around this time, Nur began to strength the defenses' of ], building a wall that still encircles the city to this day.<ref>]. 1952. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220108153655/https://zelalemkibret.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/islam-in-ethiopia-j-spencer-trimingham.pdf |date=2022-01-08 }}''. London: Oxford University Press. p. 91.</ref> In 1559, urged on by his wife, Nur once again took the offensive and invaded the ], killing Ethiopian Emperor ] in the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Button|first1=Richard|title=First Footsteps in East Africa|year=1894|publisher=Tyston and Edwards|page=12|isbn=9780705415002|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mu0MAAAAIAAJ&q=nur+harar+rule&pg=PA12|access-date=21 January 2016|archive-date=22 May 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522134647/https://books.google.com/books?id=Mu0MAAAAIAAJ&q=nur+harar+rule&pg=PA12#v=snippet&q=nur%20harar%20rule&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref> At the same time another Ethiopian army led by ] Hamalmal attacked the capital of Adal, ]. Sultan ] attempted to defend the city but was defeated and killed, thus ending the ]. Not long after this, Barentu Oromos who had been migrating north invaded the Adal Sultanate. This struggle, which was mentioned by ], led to the devastation of many regions and Nur's army was defeated at the ].{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=374}} The defensive walls managed to protect ] from the invaders, preserving it as a kind of Muslim island in an Oromo sea. However, the city then experienced a severe famine as grain and salt prices rose to unpreceded levels. According to a contemporary source, the hunger became so bad that people began to resort to eating their own children and spouses. Nur himself died in 1567 of the pestilence which spread during the famine.<ref>]. 1952. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220108153655/https://zelalemkibret.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/islam-in-ethiopia-j-spencer-trimingham.pdf |date=2022-01-08 }}''. London: Oxford University Press. p. 94.</ref>{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=247}} | |||

| Nur was succeeded by ], who relaxed his predecessor's pro-Islamic policy and signed an infamous and humiliating peace treaty with the Oromos. The treaty stated that the Oromos can freely enter to the Muslim markets and purchase goods at less than the current market price.<ref name="History of Harar & Harari">{{cite book |title=History of Harar |page=106 |url=https://www.everythingharar.com/files/History_of_Harar_and_Harari-HNL.pdf |access-date=2021-08-19 |archive-date=2020-10-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201003055338/https://www.everythingharar.com/files/History_of_Harar_and_Harari-HNL.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> This angered many Muslims and led to a rebellion, in which he was overthrown and replaced by ] in 1569. Tahla would rule for only three years before being overthrown by some of his very fanatic subjects who were intent on another jihad or holy war against the Christians. He was replaced by Uthman's grandson ] who soon carried out an expedition against the ], however this campaign would end in total disaster. As soon as the army left ] the Oromo ravaged the countryside, up to the walls of the city. ] was also defeated and killed at the ], thus permanently ending Adal aggression towards Ethiopia.<ref>J.S. Trimingham, ''Islam in Ethiopia'', pp. 96</ref> Muhammad's successor, ], fought a fierce war against the Oromos, but was unable to defeat them. Mansur would also successfully reconquer ] and ]. The tension was all the greater after the death of Nur Ibn Mujahid, the disappearance of the last of the Walashma monarch also opened a tough competition for power between emirs and descendants of ]. Ultimately, they won in April 1576, ] took the title of ], thus combining the political power of the Sultan and the religious responsibility of guiding the community, he then relocated the capital to the oasis of ] in 1577, establishing the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cuoq |first=Joseph |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hUsgUDdzYDkC&dq=umar+walasma&pg=PA125 |title=L'Islam en Éthiopie des origines au XVIe siècle |date=1981 |publisher=Nouvelles Editions Latines |isbn=978-2-7233-0111-4 |pages=266 |language=fr |access-date=2024-01-28 |archive-date=2024-05-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522134623/https://books.google.com/books?id=hUsgUDdzYDkC&dq=umar+walasma&pg=PA125#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The ] declined gradually in the next century and was destroyed by the neighboring ] nomads who made ] their capital.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Abir|first1=Mordechai|title=Ethiopia and the Red Sea|date=17 June 2016|publisher=Routledge|page=139|isbn=9781317045465|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BQ5qDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA235|access-date=19 January 2016|archive-date=22 May 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522134623/https://books.google.com/books?id=BQ5qDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA235#v=onepage&q&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Fani |first1=Sara |title=HornAfr 6thField Mission Report |date=2017 |publisher=University of Copenhagen |page=8 |url=http://www.islhornafr.eu/ReportAwsa2017.pdf |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2020-01-14 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200114065409/http://www.islhornafr.eu/ReportAwsa2017.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> In the seventeenth century the induction of ] and ] populations into Afar identity would lead to the emergence of ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bausi |first1=Alessandro |title=Ethiopia History, Culture and Challenges |date=2017 |publisher=Michigan State University Press |page=83 |isbn=978-3-643-90892-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h-g7DwAAQBAJ&dq=were+reclaimed+by+migrant+populations+from+the+highlands+(Haralla,+Dobaa)+who+were+integrated+into+Afar+ethnicity&pg=PA83 |access-date=2023-04-04 |archive-date=2023-04-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230409093701/https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Ethiopia/h-g7DwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=were+reclaimed+by+migrant+populations+from+the+highlands+%28Haralla,+Dobaa%29+who+were+integrated+into+Afar+ethnicity&pg=PA83&printsec=frontcover |url-status=live }}</ref> ]'s verdict on this "sad condition" of Adal's decadence was that whereas the ] under ] was able to reorganize and withstand the ], the Sultanate of Adal was too newly established to transcend tribal differences. The result he claims was that the nomadic people instinctively return to their "eternal disintegrating struggles" of people against people and tribe against tribe.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Cerulli |first1=Enrico |title=Islam: Yesterday and Today translated by Emran Waber |publisher=Istituto Per L'Oriente |page=218 |url=https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view |access-date=2021-09-07 |archive-date=2021-08-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210822194826/https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Ethnicity== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Ulrich Braukämper mentions that Adal was distinguished by its ethnic variety which included ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Braukämper |first1=Ulrich |title=Islamic history and culture in Southern Ethiopia: collected essays |date=2004 |publisher=Lit |location=Münster |isbn=9783825856717 |pages=37–38 |edition=2. Aufl}}</ref> Ethiopian historian ] states that Adal's central authority in the fourteenth century consisted of the Argobba, Harari and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Tamrat |first1=Taddesse |title=Review: Place Names in Ethiopian History |date=November 1991 |publisher=Journal of Ethiopian Studies |page=120 |jstor=41965996 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41965996 |access-date=2021-08-19 |archive-date=2021-07-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210713135254/https://www.jstor.org/stable/41965996 |url-status=live }}</ref> Professor ], an important figure in ], described the Adal Sultanate as consisting of many ethnic groups, but primarily Somalis and Afars.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Levine |first1=Donald N. |title=A Revised Analytical Approach to the Evolution of Ethiopian Civilization |journal=International Journal of Ethiopian Studies |date=2012 |volume=6 |issue=1/2 |page=49 |jstor=41756934 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41756934 |issn=1543-4133 |access-date=2023-07-31 |archive-date=2024-05-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522134702/https://www.jstor.org/stable/41756934 |url-status=live }}</ref> Somali scholar ] notes that Somalis were integral to the founding of the sultanate, and played a significant role in the subsequent wars with Abyssinia.<ref>{{cite book |title=Making sense of Somali history |date=2018 |publisher=Adonis & Ashley Publishers Ltd |location=London, United Kingdom |isbn=978-1909112797 |pages=36, 64}}</ref> According to Patrick Gikes and Mohammed Hassen, Adal in the sixteenth century was primarily inhabited by the sedentary ] people and the pastoral Somali people.<ref name="University of Lisbon">{{Cite journal |last1=Gikes |first1=Patrick |date=2002 |title=Wars in the Horn of Africa and the dismantling of the Somali State |url=https://cea.revues.org/1280 |journal=African Studies |publisher=University Institute of Lisbon |volume=2 |pages=89–102 |access-date=2019-04-11 |archive-date=2017-11-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171113184419/http://cea.revues.org/1280 |url-status=live }}</ref> Marriage alliances between Argobba, Harari and Somali people were also common within the Adal Sultanate.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ferry |first1=Robert |title=Quelques hypothèses sur les origines des conquêtes musulmanes en Abyssinie au XVIe siècle |year=1961 |journal=Cahiers d'Études africaines |volume=2 |issue=5 |pages=28–30 |doi=10.3406/cea.1961.2961 |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1961_num_2_5_2961 |access-date=2021-08-20 |archive-date=2021-08-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210820030140/https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1961_num_2_5_2961 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| According to Professor Lapiso Delebo, the contemporary ] are heirs to the ancient Semitic speaking peoples of the Adal region.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dilebo |first1=Lapiso |title=An introduction to Ethiopian history from the Megalithism Age to the Republic, circa 13000 B.C. to 2000 A.D. |quote="Like their direct descendants, the Adares of today, the people of ancient Shewa, Yifat, Adal, Harar and Awssa were semitic in their ethnic and linguistic origins. They were neither Somalis nor Afar. But the Somali and Afar nomads were the local subjects of the Adal." |date=2003 |publisher=Commercial Printing Enterprise |page=41 |oclc=318904173 |url=https://emu.tind.io/record/42082?ln=en |access-date=2023-04-02 |archive-date=2022-07-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220728083236/https://emu.tind.io/record/42082?ln=en |url-status=live }}</ref> Historians state the language spoken by the people of Adal as well as its rulers the Imams and Sultans would closely resemble contemporary ].<ref name="persee.fr">{{cite journal |last1=Ferry |first1=Robert |title=Quelques hypothèses sur les origines des conquêtes musulmanes en Abyssinie au XVIe siècle |year=1961 |journal=Cahiers d'Études africaines |volume=2 |issue=5 |pages=28–29 |doi=10.3406/cea.1961.2961 |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1961_num_2_5_2961 |access-date=2021-08-20 |archive-date=2021-08-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210820030140/https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1961_num_2_5_2961 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Harbeson |first1=John |title=Territorial and Development Politics in the Horn of Africa: The Afar of the Awash Valley |journal=African Affairs |year=1978 |volume=77 |issue=309 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=486 |doi=10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097023 |jstor=721961 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/721961 |access-date=2023-04-11 |archive-date=2021-09-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210910192343/https://www.jstor.org/stable/721961 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Lindahl |first1=Bernhard |title=Local history of Ethiopia |publisher=Nordic Africa Institute |page=37 |url=https://nai.uu.se/download/18.39fca04516faedec8b248c17/1580827183104/ORTAST05.pdf |access-date=2023-04-11 |archive-date=2020-03-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200327081659/https://nai.uu.se/download/18.39fca04516faedec8b248c17/1580827183104/ORTAST05.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Ethiopian historian ] and others state the Walasma led Sultanates of Ifat and Adal primarily included the Ethiopian Semitic speaking ] and ], it later expanded to comprise ] and ] peoples.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Zewde |first1=Bahru |title=A Short History of Ethiopia and the Horn |year=1998 |publisher=Addis Ababa University |page=64 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N8pRAQAAMAAJ&q=a+short+history+of+ethiopia+and+the+horn+new+Walasma+sultanate |access-date=2023-03-18 |archive-date=2023-04-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405042055/https://books.google.com/books?id=N8pRAQAAMAAJ&q=a%20short%20history%20of%20ethiopia%20and%20the%20horn%20new%20Walasma%20sultanate |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ylönen |first1=Aleksi |title=The Horn Engaging the Gulf Economic Diplomacy and Statecraft in Regional Relations |date=28 December 2023 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |page=113 |isbn=978-0-7556-3519-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wyngEAAAQBAJ&dq=largely+argobba+harari+and+harla&pg=PA113 |access-date=7 May 2024 |archive-date=22 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522135551/https://books.google.com/books?id=wyngEAAAQBAJ&dq=largely+argobba+harari+and+harla&pg=PA113#v=onepage&q=largely%20argobba%20harari%20and%20harla&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Begashaw |first1=Kassaye |title=Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies |publisher=Norwegian University of Science and Technology |page=14 |url=https://zethio.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/ethiopian-studies-volume-1.pdf |access-date=2024-04-09 |archive-date=2023-10-29 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231029001853/https://zethio.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/ethiopian-studies-volume-1.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Niane |first1=Djibril |title=General History of Africa |date=January 1984 |publisher=Heinemann Educational Books |page=427 |isbn=9789231017100 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iAcf63sQGhIC&dq=harari+and+argobba+speaking+walasma&pg=PA427}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Cambridge History of Africa |publisher=Cambridge University Press |pages=147–150 |url=https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/roland_oliver_the_cambridge_history_of_africa_vbook4you.pdf |access-date=2023-04-02 |archive-date=2023-01-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230130073307/https://sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/roland_oliver_the_cambridge_history_of_africa_vbook4you.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Between the late 1400s to mid 1500s there was a large scale migration of ] into Adal.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Martin |first1=B.G |title=Arab Migrations to East Africa in Medieval Times |journal=The International Journal of African Historical Studies |year=1974 |volume=7 |issue=3 |publisher=Boston University African Studies Center |page=376 |doi=10.2307/217250 |jstor=217250 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/217250 |access-date=2021-09-06 |archive-date=2021-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210906234259/https://www.jstor.org/stable/217250 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Among the earliest mentions of the Somali by name has come through a victory poem written by Emperor ] of Abyssinia against the king of Adal, as the Simur are said to have submitted and paid tribute. As ] writes: "Dr ] has shown that Simur was an old ] name for the Somali, who are still known by them as Tumur. Hence, it is most probable that the mention of the Somali and the Simur in relation to Yishaq refers to the king's military campaigns against Adal, where the Somali seem to have constituted a major section of the population."<ref>{{harvnb|Tamrat|1977|p=154}}.</ref> | |||

| According to Leo Africanus (1526) and ] (1760), the Adelites were of a tawny brown or olive complexion on the northern littoral, and grew swarthier towards the southern interior. They generally had long, lank hair. Most wore a cotton ] but no headpiece or sandals, with many glass and amber trinkets around their necks, wrists, arms and ankles. The king and other aristocrats often donned instead a body-length garment topped with a headdress. All were Muslims.<ref name="Leo"/><ref name="Sale">{{cite book|last1=Sale|first1=George|title=An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time, Volume 15|date=1760|publisher=T. Osborne, A. Millar, and J. Osborn|pages=361 & 367–368|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nWVjAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA361|access-date=1 July 2017}}</ref> In the southern hinterland, the Adelites lived beside pagan "]es", with whom they bartered various commodities.<ref name="Leo5153">{{cite book|last1=Africanus|first1=Leo|title=The History and Description of Africa|date=1526|publisher=Hakluyt Society|pages=51 & 53|url=https://archive.org/stream/historyanddescr03porygoog#page/n180/mode/2up|access-date=1 July 2017|quote=The land of Aian is accounted by the Arabians to be that region which lyeth betweene the narrow entrance to the Red sea, and the river Quilimanci; being upon the sea-coast for the most part inhabited by the said Arabians; but the inland-partes thereof are peopled with a black nation which are Idolators. It comprehendeth two kingdomes; Adel and Adea. Adel is a very large kingdome, and extendeth from the mouth of the Arabian gulfe to the cape of Guardafu called of olde by Ptolemey Aromata promontorium. Adea, the second kingdome of the land of Aian, situate upon the easterne Ocean, is confined northward by the kingdome of Adel, & westward by the Abassin empire. The inhabitants being Moores by religion, and paying tribute to the emperour of Abassin, are (as they of Adel before-named) originally descended of the Arabians}}</ref><ref name="Sale361">{{cite book|last1=Sale|first1=George|title=An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time, Volume 15|date=1760|publisher=T. Osborne, A. Millar, and J. Osborn|page=361|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nWVjAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA361|access-date=1 July 2017|quote=The inhabitants along this last coast are mostly white, with long lank hair; but grow more tawny, or even quite black, as you proceed towards the south. Here are plenty of negroes who live and intermarry with the Bedowin Arabs, and carry on a great commerce with them, which consists in gold, slaves, horses, ivory, etc.|archive-date=3 January 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170103004310/https://books.google.com/books?id=nWVjAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA361|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Languages== | |||

| Various languages from the ] family were spoken in the vast Adal Sultanate. ] served as a lingua franca, and was used by the ruling Walashma dynasty.<ref>{{cite book|last=Giyorgis|first=Asma|title=Aṣma Giyorgis and his work: history of the Gāllā and the kingdom of Šawā|year=1999|publisher=Medical verlag|isbn=978-3-515-03716-7|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mGcwAQAAIAAJ&q=%22Their+language+is+Arabic,+and+it+is+similar+to%22|page=257|access-date=2023-03-23|archive-date=2023-04-04|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404115836/https://books.google.com/books?id=mGcwAQAAIAAJ&q=%22Their+language+is+Arabic,+and+it+is+similar+to%22|url-status=live}}</ref> According to the 19th-century Ethiopian historian Asma Giyorgis suggests that the Walashma dynasty themselves spoke ].<ref name="history of sawa">{{cite book|last=Giyorgis|first=Asma|title=Aṣma Giyorgis and his work: history of the Gāllā and the kingdom of Šawā|year=1999|publisher=Medical verlag|isbn=9783515037167|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mGcwAQAAIAAJ&q=walasma+language|page=257|access-date=2021-08-20|archive-date=2024-05-22|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240522140659/https://books.google.com/books?id=mGcwAQAAIAAJ&q=walasma+language|url-status=live}}</ref> According to Robert Ferry, Adal's aristocracy in the ] era which consisted of imams, emirs and sultans spoke a language resembling modern ].<ref name="persee.fr"/> British historian ] states Walasma leaders moving their capital from ] to Adal set in motion the evolution of Harari and ] within ] and its environs.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=John |title=Cambridge History of Africa |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=150 |url=https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/roland_oliver_the_cambridge_history_of_africa_vbook4you.pdf |access-date=2023-04-02 |archive-date=2023-01-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230130073307/https://sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/roland_oliver_the_cambridge_history_of_africa_vbook4you.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> According to Jeffrey M. Shaw, the main inhabitants of the Adal Sultanate spoke ] languages.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Shaw |first1=Jeffrey M. |title=The Ethiopian-Adal War, 1529-1543: the conquest of Abyssinia |date=2021 |publisher=Helion & Company |location=Warwick |isbn=9781914059681 |page=53}}</ref> In ], the port city of Adal Sultanate, the ] was mainly spoken.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=John |title=Cambridge History of Africa |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=139 |url=https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/roland_oliver_the_cambridge_history_of_africa_vbook4you.pdf |access-date=2023-04-02 |archive-date=2023-01-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230130073307/https://sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/archive-files3/roland_oliver_the_cambridge_history_of_africa_vbook4you.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| ] was the main river of the Adal and Ifat sultanates and provided abundant agricultural produce and fresh water.]] | |||

| ]'s notes on ] which was a large port of the sultanate]] | |||

| One of the empire's most wealthy provinces was Ifat it was well watered, by the large river ]. Additionally, besides the surviving ], at least five other rivers in the area between Harar and Shawa plateau existed.<ref>Understanding the Drivers of Drought in Somalia by MSH Said Page 27</ref> The general area was well cultivated, densely populated with numerous villages adjoining each other. Agricultural produce included three main cereals, wheat, sorghum and teff, as well as beans, aubergines, melons, cucumbers, marrows, cauliflowers and mustard. Many different types of fruit were grown, among them bananas, lemons, limes, pomegranates, apricots, peaces, citrons mulberries and grapes. Other plants included sycamore tree, sugar cane, from which kandi, or sugar was extracted and inedible wild figs. | |||

| The province also grew the stimulant plant Khat. Which was exported to ]. Adal was abundant in large numbers of cattle, sheep, and some goats. There was also chickens. Both buffaloes and wild fowl were sometimes hunted. The province had a great reputation for producing butter and honey.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=46}} | |||

| Whereas provinces such as ], surrounding regions of ] was known for it cotton cultivation and an age old weaving industry, while the ] region produced salt which was an important trading item.<ref>Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays by Ulrich Braukämper Page 79</ref> | |||

| ] was a wealthy city and abundantly supplied with provisions. It possessed grain, meat, oil, honey and wax. Furthermore, the citizens had many horses and reared cattle of all kinds, as a result they had plenty of butter, milk and flesh, as well as a great store of millet, barley and fruits; all of which was exported to Aden. The port city was so well supplied with victuals that it exported it's surplus to ], ], ] and "All Arabia" which then was dependent on the supplies/produce from the city which they favoured above all. ] was described as a "Port of much provisions for Aden, and all parts of Arabia and many countries and Kingdoms". | |||

| The Principal exports, according the Portuguese writer Corsali, were gold, ivory and slaves. A "great number" of the latter was captured from the ], then were exported through the port of ] to Persia, Arabia, Egypt and India. | |||

| As a result of this flourishing trade, the citizens of ] accordingly lived "extremely well" and the city was well built guarded by many soldiers on both foot and horses.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=127}} | |||

| The kingdoms agricultural and other produce was not only abundant but also very cheap according to Maqrizi thirty pounds of meat sold for only half a dirhem, while for only four dirhems you could purchase a bunch of about 100 Damascus grapes.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=49}} | |||

| Trade on the upland river valleys themselves connected with the coast to the interior markets. Created a lucrative caravan trade route between Ethiopian interior, the ] highlands, Eastern Lowlands and the coastal cities such as ] and ].<ref>Great Events from History: The Renaissance & early modern era, 1454-1600, Volum 1 By Christina J. Moose Page 94</ref> The trade from the interior was also important for the reason that included gold from the Ethiopian territories in the west, including Damot and an unidentified district called Siham. The rare metal sold for 80 to 120 dirhems per ounce.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=47}} The whole empire and the wider region was interdependent on each other and formed a single economy and at the same time a cultural unit interconnected with several important trade routes upon which the economy and the welfare of the whole area depended.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=11}} | |||

| The nobility of Adal also apparently had a fair taste for luxury, the commercial relations that existed between the Adal Sultanate and the rulers of the ] allowed Muslims to obtain luxury items that Christian Ethiopians, whose relations with the outside world were still blocked, could not acquire, a Christian document describing ] relates:<blockquote>"And the robes and those of his leaders were adorned with silver and shone on all sides. And the dagger which he carried at his side was richly adorned with gold and precious stones; and his amulet was adorned with drops of gold; and the inscriptions on the amulet were of gold paint. And his parasol came from the land of Syria and it was such beautiful work that those who looked at it marveled, and winged serpents were painted on it."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fasi |first=M. El |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sdjfwGxt0e0C&dq=sabr+ad-din+Adal&pg=PA622 |title=L'Afrique du VIIe au XIe siècle |date=1990 |publisher=UNESCO |isbn=978-92-3-201709-3 |pages=623 |language=fr |access-date=2024-01-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240331152557/https://books.google.com/books?id=sdjfwGxt0e0C&dq=sabr+ad-din+Adal&pg=PA622 |archive-date=2024-03-31 |url-status=live}}</ref></blockquote>During its existence, Adal had relations and engaged in trade with other polities in ], the ], Europe and ]. Many of the historic cities in the Horn of Africa such as ], ], ] and ] flourished under its reign with ], ]s, ]s, ] and ]s. Adal attained its peak in the 14th century, trading in slaves, ivory and other commodities with ] and kingdoms in Arabia through its chief port of Zeila.<ref name="Lewispd"/> The cities of the empire imported intricately coloured glass bracelets and Chinese ] for palace and home decoration.<ref>The Archaeology of Islam in Sub Saharan Africa, p. 72/73</ref> Adal also used imported currency such as Egyptian dinars and dirhems.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1997|p=8}} | |||

| ==Military== | |||

| The ] was divided into several sections such as the ] consisting of ], ] and ]s that were commanded by various ]s and ]s. These forces were complemented by a ] force and eventually, later in the empire's history, by ]-] and ]s during the Conquest of Abyssinia. The various divisions were symbolised with a distinct flag. | |||