| Revision as of 23:50, 3 July 2012 editIrānshahr (talk | contribs)3,706 edits Reverted to revision 495119972 by John of Reading: Restored prose on Iraqi-Iranian bonds. (TW)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:40, 2 January 2025 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,436,024 edits Altered title. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Dominic3203 | Category:Articles contradicting other articles | #UCB_Category 39/267 | ||

| (953 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Sociocultural region in West and Central Asia}} | |||

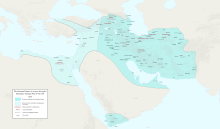

| ] and its bordering ]s,<ref name="IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN">{{cite web|title=IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN|publisher=]|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-i-lands-of-iran}}</ref> extending from ] and the ] in the west, to the ] in the east, and from the ] in the north to the ] and ] in the south.]] | |||

| {{Seealso|Indo-Persian culture|Turco-Persian tradition}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Multiple issues|section=| | |||

| {{Synthesis |date=August 2023}} | |||

| {{Over-quotation|date=August 2023}} | |||

| }}{{Contains special characters|Perso-Arabic}} | |||

| ] at its greatest extent {{Circa|620}}, under ]]]{{History of Greater Iran sidebar}} | |||

| '''Greater Iran''' or '''Greater Persia''' ({{langx|fa|ایران بزرگ}} {{Transliteration|fa|Irān-e Bozorg}}), also called the '''Iranosphere''' or the '''Persosphere''', is an expression that denotes a wide socio-cultural region comprising parts of ], the ], ], ], and ] (specifically the ])—all of which have been affected, to some degree, by the ] and the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Frye |first1=Richard Nelson |year=1962 |title=Reitzenstein and Qumrân Revisited by an Iranian, Richard Nelson Frye, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Oct. 1962), pp. 261–268 |url=https://www.jstor.org/pss/1508723 |journal=The Harvard Theological Review |volume=55 |issue=4 |pages=261–268 |doi=10.1017/S0017816000007926 |jstor=1508723 |s2cid=162213219}}</ref><ref>. (2007), 39: pp 307–309 Copyright © 2007 Cambridge University Press.</ref> | |||

| It is defined by having long been ruled by the dynasties of various ],{{NoteTag|These include the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].}}<ref name="Marcinkowski">{{cite book|last=Marcinkowski|first=Christoph|title=Shi'ite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts|year=2010|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-643-80049-7|page=83}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url = http://azadegan.info/files/Dr.Frye-discusses-greater-Iran-on-CNN.mp4 |title = Interview with Richard N. Frye (CNN) <!-- |access-date = 2007 --> |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160423185051/http://azadegan.info/files/Dr.Frye-discusses-greater-Iran-on-CNN.mp4 |archive-date = 2016-04-23 |url-status = dead }}</ref><ref> I use the term Iran in an historical contextPersia would be used for the modern state, more or less equivalent to "western Iran". I use the term "Greater Iran" to mean what I suspect most Classicists and ancient historians really mean by their use of Persia—that which was within the political boundaries of States ruled by Iranians.</ref> under whom the local populaces gradually incorporated some degree of Iranian influence into their cultural and/or linguistic traditions;{{notetag|For example, those regions and peoples in the ] that were not under direct Iranian rule.}} or alternatively as where a considerable number of Iranians settled to still maintain communities who patronize their respective cultures,{{notetag|Such as in the western parts of ], ] and ].}} geographically corresponding to the areas surrounding the ].<ref name="IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN">{{cite web|title=IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN|publisher=]|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-i-lands-of-iran}}</ref><ref>. Clive Holes. 2001. Page XXX. {{ISBN|978-90-04-10763-2}}.</ref> It is referred to as the "Iranian Cultural Continent" by '']''.<ref>{{Unbulleted list citebundle | {{cite web |url=https://www.iranicaonline.org/uploads/pdfs/2008-eif-annual-report.pdf |title= 2008 Annual Report |year=2009 |website=Encyclopædia Iranica |publisher=Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University |location=New York |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230812060239/https://www.iranicaonline.org/uploads/pdfs/2008-eif-annual-report.pdf |archive-date=2023-08-12 |quote=Covering a multi-lingual and multi-ethnic cultural continent, the Encyclopædia Iranica’s scope encompasses all aspects of the life, history, and civilization of all the peoples who speak or once spoke an Iranian language |quote-page=5}}. | {{cite magazine |last1=Boss |first1=Shira J. |date=November 2003 |title=Encyclopaedia Iranica: Comprehensive research project about the "Iranian Cultural Continent" thrives on Riverside Drive |url=https://www.college.columbia.edu/cct_archive/nov03/features5.html |url-status=live |magazine=Columbia College Today |location=New York |publisher=] Office of Alumni Affairs and Development |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=32–33 |issn=0572-7820 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210215041808/https://www.college.columbia.edu/cct_archive/nov03/features5.html |archive-date=2021-02-15}} Scan of print version available at {{Internet Archive|id=ldpd_12981092_045|name=''Columbia College Today'', v. 30 (2003–04)|page=126}}. | {{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2008/12/encyclopaedia-iranica-an-iranian-love-story.html |title=Encyclopaedia Iranica: an Iranian love story |last1=Niknejad |first1=Kelly Golnoush |date=2008-12-07 |orig-date=first published March 2005 |department=] |website=] |publisher=] |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100426140933/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2008/12/encyclopaedia-iranica-an-iranian-love-story.html |archive-date=2010-04-26}} }}</ref> | |||

| {{History of Greater Iran}} | |||

| ] (550 BC–330 BC)]] | |||

| ] (247 BC–224 AD)]] | |||

| ] (224–651)]] | |||

| ] (1501–1722)]] | |||

| {{Contains Perso-Arabic text}} | |||

| '''Greater Iran''' (in {{lang-fa|'''<big>ایرانِ بُزُرگ</big>'''}}</big> ''Irān-e Bozorg'', or <big>'''{{lang|fa|ایران زَمین}}'''</big> ''Irānzamīn'' "Iranian soil" or <big>'''{{lang|fa|ایران شهر}}'''</big> ''Irānshahr'' "The Land of Iran") refers to the regions of ], ], and ] that have significant ]ian cultural influence and have historically been ruled by ].<ref name=Marcinkowski>{{cite book|last=Marcinkowski|first=Christoph|title=Shi'ite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts|year=2010|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-643-80049-7|page=83|quote=The 'historical lands of Iran' – 'Greater Iran' – were always known in the Persian language as ''Irānshahr'' or ''Irānzamīn''. Both terms refer to the Iranian plateau in addition to the Persianate world at large, those regions that had been historically under significant Persian cultural influence, roughly corresponding to the territories ruled over by the ancient Parthians and Sasanids – i.e., in addition to 'Iran proper', also the Caucasus, Mesopotamia (Iraq), Central Asia, and large parts of what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan and conforming to the Persian 'historical understanding' of the 'full territorial extent' of Iran. The capital of this entity was, at times, situated in what is now Iraq.}}</ref><ref>] http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=8599016121144917550 "I spent all my life working in Iran. and as you know I don't mean Iran of today, I mean Greater Iran, the Iran which in the past, extended all the way from China to borders of Hungary and from other Mongolia to Mesopotamia"</ref><ref>Richard Nelson Frye, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Oct., 1962), pp. 261-268 http://www.jstor.org/pss/1508723 I use the term Iran in an historical contextPersia would be used for the modern state, more or less equivalent to "western Iran". I use the term "Greater Iran" to mean what I suspect most Classicists and ancient historians really mean by their use of Persia - that which was within the political boundaries of States ruled by Iranians.</ref> It roughly corresponds to the territory on the ] and its bordering ]s,<ref name="IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN"/> stretching from ], the ], and ] in the west, to the ] of ] in the east. It is also referred to as '''Greater Persia''',<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=978-0-521-88782-3&ss=exc |title=Justice, Punishment and the Medieval Muslim Imagination |series=Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization |last=Lange |first=Christian |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-88782-3 }} Lange: "I further restrict the scope of this study by focusing on the lands of Iraq and greater Persia (including Khwārazm, Transoxania, and Afghanistan)."</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.mazdapublisher.com/BookDetails.aspx?BookID=285 |title=Gobineau and Persia: A Love Story |last=Gobineau |first=Joseph Arthur |last2=O'Donoghue |first2=Daniel |isbn=1-56859-262-0}} O'Donoghue: "...all set in the greater Persia/Iran which includes Afghanistan".</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Shiels |first=Stan |title=Stan Shiels on centrifugal pumps: collected articles from "World Pumps" magazine |publisher=Elsevier |year=2004 |pages=11–12, 18 |isbn=1-85617-445-X |url=http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=SOTRAMbmb2kC }} Shiels: "During the Sassanid period the term ''Eranshahr'' was employed to denote the region also known as Greater Iran..." Also: "...the Abbasids, who with Persian assistance assumed the Prophet's mantle and transferred their capital to Baghdad three years later; thus, on a site close to historic Ctesiphon and even older Babylon, the caliphate was established within the bounds of Greater Persia."</ref> while the ] uses the term '''Iranian Cultural Continent'''.<ref></ref> | |||

| Throughout the 16th–19th centuries, Iran lost many of the territories that had been conquered under the ] and ]. | |||

| The term 'Iran' is not limited to the modern state, more or less equivalent to western Iran. Iran includes all the political boundaries ruled by the Iranian including Mesopotamia and usually Armenia and Transcaucasia.<ref>Reitzenstein and Qumrân Revisited by an Iranian, Richard Nelson Frye, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Oct. , 1962), pp. 261-268 http://www.jstor.org/pss/1508723</ref><ref>International Journal of Middle East Studies (2007), 39: pp 307-309 Copyright © 2007 Cambridge University Press http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=1009412</ref> In a sense the concept of Greater Iran, starts from the history that originated with the first ] or the Achaemenid Empire in ] (Fars), and in fact is synonymous with ] in many aspects. Persia lost many of its territories gained under the ], including Iraq to the ] (via ] in 1555 and ] in 1639), Afghanistan to the ] (via ] in 1857<ref>{{cite book|title=Wars and peace treaties, 1816-1991|author=Erik Goldstein|publisher=Psychology Press|year=1992|pages=72–73|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=_sZpuJhvK_4C&pg=PA72&dq=treaty+of+paris+Afghanistan&hl=en&ei=HeQyTZj1OYKclgew2pnHCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CEEQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=treaty%20of%20paris%20Afghanistan&f=false}}</ref> and MacMahon Arbitration in 1905<ref>{{cite book|title=A history of Persia, Volume 2|author=Sir Percy Molesworth Sykes|date=Macmillan and co.|year=1915|pages=469|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=lm_UAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA469&dq=Macmahon+arbitration+persia&hl=en&ei=EeUyTdySEcH_lgeDkcGXCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref>), and its Caucasus territories to ] in the 18th and 19th centuries.<ref>{{cite book|title=War and peace in Qajar Persia: implications past and present|author=Roxane Farmanfarmaian|year=2008|publisher=Psychology Press|pages=4|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Q_CPdClFR2cC&pg=PA4&dq=Qajar+loss+of+Afghanistan&hl=en&ei=1NYyTeqmNYOclge2g9TdCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Qajar%20loss%20of%20Afghanistan&f=false}}</ref> The ] in 1813 resulted in ] ceding ], ], and eastern ] to ].<ref>{{cite book|title=A Collection of Treaties, Engagements, and Sunnuds, Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries: Persia and the Persian Gulf|author=India. Foreign and Political Dept.|year=1892|publisher=G. A. Savielle and P. M. Cranenburgh, Bengal Print. Co|pages=x (10)|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=C7L7CSjut9wC&pg=PR10&dq=treaty+of+gulistan&hl=en&ei=mucyTavNDsSqlAeN-ZTWDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDkQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=treaty%20of%20gulistan&f=false}}</ref> The ] of 1828, after the ] permanently severed the Caucasian provinces from Iran and settled the modern boundary along the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Pivot of the universe: Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831-1896|author=Abbas Amanat|publisher=I.B.Tauris|year=1997|pages=16|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=L3qqb8hQWFYC&pg=PA16&dq=Qajar+loss+of+territory+to+Russia&hl=en&ei=ldgyTdv9G8X_lgeP6oiQCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Qajar%20loss%20of%20territory%20to%20Russia&f=false}}</ref> | |||

| The ] resulted in the loss of present-day ] to the ], as outlined in the ] in 1555 and the ] in 1639. | |||

| Due to this geographic diversity, newly independent nations under Russian or British involvement, while maintaining a cultural or language connection with Persia, developed their own unique socio-political and cultural paths. Some of these nations included ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. In 1935 under the rule of ], the ] '']'' was made the official international name.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Persian puzzle: the conflict between Iran and America|author=Kenneth M. Pollack|year=2005|publisher=Random House, Inc.|pages=38|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ZmAW881sDEgC&pg=PA38&dq=Persia+changed+name+to+Iran&hl=en&ei=o-oyTcmdDYLGlQfErKWYCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> From a native Persian perspective, both Iran and Persia are interchangeable but until then the official name of Iran was Persia, but now both terms are interchangeably used even though Iran is the official political title. | |||

| Simultaneously, the ] resulted in the loss of the Caucasus to the ]: the ] in 1813 saw Iran cede present-day ], ], and most of ];<ref>{{cite book |author=India. Foreign and Political Dept. |url=https://archive.org/details/acollectiontrea14deptgoog |title=A Collection of Treaties, Engagements, and Sunnuds, Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries: Persia and the Persian Gulf |publisher=G. A. Savielle and P. M. Cranenburgh, Bengal Print. Co |year=1892 |pages=x (10) |quote=treaty of gulistan.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Mikaberidze |first1=Alexander |title=Historical Dictionary of Georgia |date=2015 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-4422-4146-6 |pages=348–349 |quote=Persia lost all its territories to the north of the Aras River, which included all of Georgia, and parts of Armenia and Azerbaijan.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Olsen |first1=James Stuart |title=Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism |last2=Shadle |first2=Robert |date=1991 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-26257-9 |page=314 |quote=In 1813 Iran signed the Treaty of Gulistan, ceding Georgia to Russia.}}</ref> the ] in 1828 saw Iran cede present-day ], the remainder of Azerbaijan, and ], setting the northern boundary along the ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Roxane Farmanfarmaian |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q_CPdClFR2cC&q=Qajar+loss+of+Afghanistan&pg=PA4 |title=War and peace in Qajar Persia: implications past and present |publisher=Psychology Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-203-93830-0 |page=4}}</ref>{{sfn|Fisher|Avery|Hambly|Melville|1991|p=329}} | |||

| Parts of ] were lost to the ] through the ] in 1857 and the ] in 1905.<ref>{{cite book |author=Erik Goldstein |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_sZpuJhvK_4C&q=treaty+of+paris+Afghanistan&pg=PA72 |title=Wars and peace treaties, 1816-1991 |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1992 |isbn=978-0-203-97682-1 |pages=72–73}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=A history of Persia, Volume 2|author=Sir Percy Molesworth Sykes|publisher=Macmillan and co.|year=1915|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924088418466|quote=Macmahon arbitration persia.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The name |

The name "Iran", meaning "land of the ]s", is the ] continuation of the old ] plural ''aryānām'' (proto-Iranian, meaning "of the Aryans"), first attested in the ] as ''airyānąm'' (the text of which is composed in ], an old ] spoken in northeastern Greater Iran, or in what are now ], ], ] and ]).<ref name="Encyclopaedia Iranica1">{{cite web | url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/zoroastrianism-i-historical-review | title=ZOROASTRIANISM i. HISTORICAL REVIEW | access-date=2011-01-14 | author=William W. Malandra | date=2005-07-20}}</ref><ref name="Encyclopaedia Iranica">{{cite web | url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/eastern-iranian-languages | title=EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES | access-date=2011-01-14 | author=Nicholas Sims-Williams}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran | title=IRAN | access-date=2011-01-14}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/avestan-language | title=AVESTAN LANGUAGE I-III | access-date=2011-01-14 | author=K. Hoffmann}}</ref> | ||

| The proto-Iranian term ''aryānām'' is present in the term '']'', the homeland of ] and ], near the provinces of ], ], ], etc., listed in the first chapter of the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/eran-wez|title=ĒRĀN-WĒZ|work=iranicaonline.org|access-date=9 December 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/zoroaster-ii-general-survey|title=ZOROASTER ii. GENERAL SURVEY|work=iranicaonline.org|access-date=9 December 2015}}</ref> The Avestan evidence is confirmed by ] sources: ] is spoken of as being between ] and the ].<ref name="Encyclopaedia Iranica2">{{cite web | url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iranian-identity-ii-pre-islamic-period | title=IRANIAN IDENTITY ii. PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD | access-date=2011-01-14 | author=Ahmad Ashraf}}</ref> | |||

| Although, up until the end of the ] in the 3rd century C.E, idea of “Irān“ had an ethnic, linguistic, and religious value, it did not yet have a political import. The idea of an “Iranian“ empire or kingdom in a political sense is a purely ] one. It was the result of a convergence of interests between the new dynasty and the ] clergy, as we can deduce from the available evidence. This convergence gave rise to the idea of an Ērān-šahr “Kingdom of the Iranians,” which was “ēr“ (] equivalent of ] “ariya“ and Avestan “airya“).<ref name="Encyclopaedia Iranica"/> | |||

| However, this is a ] pronunciation of the name Haroyum/Haraiva (]), which the Greeks called 'Aria'<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/aria/index.htm|title=Haroyu|author=Ed Eduljee|work=heritageinstitute.com|access-date=9 December 2015}}</ref> (a land listed separately from the homeland of the Aryans).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/aryans/location.htm|title=Aryan Homeland, Airyana Vaeja, Location. Aryans and Zoroastrianism.|author=Ed Eduljee|work=heritageinstitute.com|access-date=9 December 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/aryans/airyanavaeja.htm|title=Aryan Homeland, Airyana Vaeja, in the Avesta. Aryan lands and Zoroastrianism.|author=Ed Eduljee|work=heritageinstitute.com|access-date=9 December 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| ] notes that while "A general assumption is often made that the various Iranian peoples of 'greater Iran'—a cultural area that streched from Mesopotamia and the Caucasus into ], ], Bactria, and the ] and included Persians, Medes, Parthians and Sogdians among others—were all 'Zoroastrians' in pre-Islamic times... This view, even though common among serious scholars, is almost certainly overstated." Foltz argues that "While the various Iranian peoples did indeed share a common pantheon and pool of religious myths and symbols, in actuality a variety of deities were worshipped—particularly Mitra, the god of covenants, and Anahita, the goddess of the waters, but also many others—depending on the time, place, and particular group concerned.".<ref>], "Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of globalization", Palgrave Macmillan, rev. 2nd edition, 2010. pg 27</ref> | |||

| To the Ancient Greeks, Greater Iran ended at the Indus.<ref>J.M. Cook, "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire" in | |||

| Ilya Gershevitch, William Bayne Fisher, J. A. Boyle "Cambridge History of Iran", Vol 2. pg 250. Excerpt: "To the Greeks, Greater Iran ended at the Indus".</ref> | |||

| While up until the end of the ] in the 3rd century CE, the idea of "Irān" had an ethnic, linguistic, and religious value, it did not yet have a political import. The idea of an "Iranian" empire or kingdom in a political sense is a purely ] one. It was the result of a convergence of interests between the new dynasty and the ] ], as we can deduce from the available evidence. | |||

| ] defines Greater Iran as including "much of the Caucasus, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Central Asia, with cultural influences extending to China and western India." According to Frye, "Iran means all lands and peoples where Iranian languages were and are spoken, and where in the past, multi-faceted Iranian cultures existed."<ref>], ''Greater Iran'', ISBN 1-56859-177-2 p.''xi''</ref> | |||

| This convergence gave rise to the idea of an Ērān-šahr "Kingdom of the Iranians", which was "ēr" (] equivalent of ] "ariya" and Avestan "airya").<ref name="Encyclopaedia Iranica2" /> | |||

| According to ] and ] most of Western ''greater Iran'' spoke SW Iranian languages in the Achaemenid era while the Eastern territory spoke Eastern Iranian languages related to Avesta.<ref>Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture, London and Chicago: Fitzroy-Dearborn, ISBN 1-884964-98-2. pg 307: "Dialetically, Old Persian is regarded as a southwestern Iranian language in contrast to the east Iranian Avestan which covered most of the rest of Greater Iran</ref> | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| George Lane also states that after the dissolution of the ], the ] became rulers of greater Iran<ref>George Lane, "Daily life in the Mongol empire", Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. pg 10" The year following 1260 saw the empire irrevocably split but also signaled the emergence of the two greatest achievements of the house of Chinggis, namely the Yuan dynasty of greater China and the Il-Khanid dynasty of greater Iran.</ref> and ], according to Judith G. Kolbas, was the ruler of this expanse between 1304-1317 A.D.<ref>Judith G. Kolbas, "The Mongols in Iran", Excerpt from 399: "Uljaytu, Ruler of Greater Iran from 1304-1317 A.D."</ref> | |||

| ] defines Greater Iran as including "''much of the Caucasus, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Central Asia, with cultural influences extending to China and western India''." | |||

| According to him, "''Iran means all lands and peoples where Iranian languages were and are spoken, and where in the past, multi-faceted Iranian cultures existe''d."<ref>], ''Greater Iran'', {{ISBN|978-1-56859-177-3}} p.''xi''</ref> | |||

| Primary sources, including Timurid historian Mir Khwand, define Iranshahr (Greater Iran) as extending from the Euphrates to the Oxus<ref>Mīr Khvānd, Muḥammad ibn Khāvandshāh, Tārīkh-i rawz̤at al-ṣafā. Taṣnīf Mīr Muḥammad ibn Sayyid Burhān al-Dīn Khāvand Shāh al-shahīr bi-Mīr Khvānd. Az rū-yi nusakh-i mutaʻaddadah-i muqābilah gardīdah va fihrist-i asāmī va aʻlām va qabāyil va kutub bā chāphā-yi digar mutamāyiz mībāshad. Markazī-i Khayyām Pīrūz . ایرانشهر از کنار فرات تا جیهون است و وسط آبادانی عالم است. Iranshahr streches from the Euphrates to the Oxus, and it is the center of the prosperity of the World.</ref> | |||

| ] notes that while "''A general assumption is often made that the various Iranian peoples of 'greater Iran'—a cultural area that stretched from Mesopotamia and the Caucasus into ], ], Bactria, and the ] and included Persians, ], Parthians and ] among others—were all 'Zoroastrians' in pre-Islamic times... This view, even though common among serious scholars, is almost certainly overstated''." He argues that "''While the various Iranian peoples did indeed share a common ] and pool of religious myths and ], in actuality a variety of ] were worshipped—particularly ], the god of covenants, and ], the goddess of the waters, but also many others—depending on the time, place, and particular group concerned''".<ref>], "Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of globalization", Palgrave Macmillan, rev. 2nd edition, 2010. pg 27</ref> | |||

| Traditionally, and until recent times, ethnicity has never been a defining separating criterion in these regions. In the words of Richard Nelson Frye: | |||

| To the ], Greater Iran ended at the ] located in ].<ref>J.M. Cook, "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire" in | |||

| {{cquote|Many times I have emphasized that the present peoples of Central Asia, whether Iranian or Turkic speaking, have one culture, one religion, one set of social values and traditions with only language separating them.}} | |||

| Ilya Gershevitch, William Bayne Fisher, J. A. Boyle "Cambridge History of Iran", Vol 2. pg 250. Excerpt: "To the Greeks, Greater Iran ended at the Indus".</ref> | |||

| According to ] and ] most of Western ''greater Iran'' spoke Southwestern Iranian languages in the Achaemenid era while the Eastern territory spoke Eastern Iranian languages related to Avestan.<ref>Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture, London and Chicago: Fitzroy-Dearborn, {{ISBN|978-1-884964-98-5}}. pg 307: "Dialectically, Old Persian is regarded as a southwestern Iranian language in contrast to the east Iranian Avestan which covered most of the rest of Greater Iran. However, it is important to note that during the Achaemeid era, the official language of the empire was ], which was the mother tongue of the ancient , since it was the language of literature, religion, and science at that time. language had a great impact on Persian and survived as the dominant language in the middle east until the .</ref> | |||

| Only in modern times did western colonial intervention and ethnicity tend to become a dividing force between the provinces of Greater Iran. As ] states, "ethnic nationalism is largely a nineteenth century phenomenon, even if it is fashionable to retroactively extend it."<ref>]. ''Eternal Iran''. Palgrave Macmillan. 2005 ISBN 1-4039-6276-6 p.23</ref> "Greater Iran" however has been more of a cultural super-state, rather than a political one to begin with. | |||

| ] also states that after the dissolution of the ], the ] became rulers of greater Iran<ref>George Lane, "Daily Life in the Mongol Empire", Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. pg 10" The year following 1260 saw the empire irrevocably split but also signaled the emergence of the two greatest achievements of the house of Chinggis, namely the Yuan dynasty of greater China and the Il-Khanid dynasty of greater Iran.</ref> and ], according to Judith G. Kolbas, was the ruler of this expanse between 1304 and 1317 A.D.<ref>Judith G. Kolbas, "The Mongols in Iran", Excerpt from 399: "Uljaytu, Ruler of Greater Iran from 1304 to 1317 A.D."</ref> | |||

| In the work ''Nuzhat al-Qolub'' (نزهه القلوب), the medieval geographer ] wrote: | |||

| ], including Timurid historian ], define Iranshahr (Greater Iran) as extending from the ] to the ]<ref>Mīr Khvānd, Muḥammad ibn Khāvandshāh, Tārīkh-i rawz̤at al-ṣafā. Taṣnīf Mīr Muḥammad ibn Sayyid Burhān al-Dīn Khāvand Shāh al-shahīr bi-Mīr Khvānd. Az rū-yi nusakh-i mutaʻaddadah-i muqābilah gardīdah va fihrist-i asāmī va aʻlām va qabāyil va kutub bā chāphā-yi digar mutamāyiz mībāshad. Markazī-i Khayyām Pīrūz . {{lang|fa|{{nastaliq|ایرانشهر از کنار فرات تا جیهون است و وسط آبادانی عالم است|fa}}}}. Iranshahr stretches from the Euphrates to the Oxus, and it is the center of the prosperity of the World.</ref> | |||

| چند شهر است اندر ایران مرتفع تر از همه<br /> | |||

| ''Some cities of Iran are better than the rest,''<br /> | |||

| بهتر و سازنده تر از خوشی آب و هوا<br /> | |||

| ''these have pleasant and compromising weather,''<br /> | |||

| گنجه پر گنج در اران صفاهان در عراق<br /> | |||

| ''The wealthy ] of ], and ] in ],''<br /> | |||

| در خراسان مرو و طوس در روم باشد اقسرا<br /> | |||

| ''] and ] in ], and ] (Aqsara) too.'' | |||

| The ''Cambridge History of Iran'' takes a geographical approach in referring to the "historical and cultural" entity of "Greater Iran" as "areas of Iran, parts of Afghanistan, |

The '']'' takes a geographical approach in referring to the "historical and cultural" entity of "Greater Iran" as "areas of Iran, parts of Afghanistan, Chinese and ]".<ref>''The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. III: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods'', ], Review author: ], ], </ref> | ||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| ] Coin of ]|An ] Coin of ] (r. 1736–1747), reverse: "Coined on gold the word of kingdom in the world, Nader of '''Greater Iran''' and the world-conqueror king."<ref>Numista: .</ref>]] | |||

| Greater Iran is called ''Iranzamin'' (ایرانزمین) which means "The Land of Iran". ''Iranzamin'' was in the mythical times opposed to the ''Turanzamin'' the Land of ], which was located in the upper part of Central Asia.<ref>], ], see under entry "Turan"</ref> | |||

| Greater Iran is called ''Iranzamin'' ({{lang|fa|{{nastaliq|ایرانزمین|fa}}}}) which means "Iranland" or "The Land of Iran". ''Iranzamin'' was in the mythical times as opposed to the ''Turanzamin'', "The Land of ]", which was located in the upper part of Central Asia.<ref>], ], see under entry "Turan"</ref>{{verify source |date=September 2023}} | |||

| In the pre-Islamic period, Iranians distinguished two main regions in the territory they ruled, one Iran and the other ''Aniran''. By Iran they meant all the regions inhabited by ]. That region was much vaster than it is today. This notion of ''Iran'' as a territory (opposed to ''Aniran'') can be seen as the core of early Greater Iran. Later many changes occurred in the boundaries and areas where Iranians lived but the languages and culture remained the dominant medium in many parts of the Greater Iran. | |||

| With ] continuously advancing south in the course of two wars against Persia, and the treaties of Turkmenchay and Gulistan in the western frontiers, plus the unexpected death of ] in 1833, and the murdering of Persia's Grand ] (]), many Central Asian khanates began losing hope for any support from Persia against the ]ist armies.<ref>], ''Kharazm: What do I know about Iran?''. 2004. {{ISBN|978-964-379-023-3}}, p.78</ref> The Russian armies occupied the ] coast in 1849, ] in 1864, ] in 1867, ] in 1868, and ] and ] in 1873. | |||

| As an example, the Persian language (referred to, in Persian, as ''Farsi'') was the main literary language and the language of correspondence in Central Asia and Caucasus prior to the Russian occupation, Central Asia being the birthplace of modern Persian language. Furthermore, according to the British government, Persian language was also used in ], prior to the British Occupation and Mandate in 1918-1932 . | |||

| :''"Many Iranians consider their natural sphere of influence to extend beyond Iran's present borders. After all, Iran was once much larger. Portuguese forces seized islands and ports in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 19th century, the Russian Empire wrested from ]'s control what is today Armenia, ], and part of Georgia. Iranian elementary school texts teach about the Iranian roots not only of cities like ], but also cities further north like ] in southern Russia. The ] lost much of his claim to western Afghanistan following the Anglo-Iranian war of 1856-1857. Only in 1970 did a ] sponsored consultation end Iranian claims to ] over the ] island nation of ]. In centuries past, Iranian rule once stretched westward into modern Iraq and beyond. When the western world complains of Iranian interference beyond its borders, the Iranian government often convinced itself that it is merely exerting its influence in lands that were once its own. Simultaneously, Iran's losses at the hands of outside powers have contributed to a sense of grievance that continues to the present day."'' -] of the ]<ref>]. ''Eternal Iran''. Palgrave. 2005. Coauthored with ]. {{ISBN|978-1-4039-6276-8}} p.9,10</ref> | |||

| With ] continuously advancing south in the course of two wars against Persia, and the treaties of Turkmenchay and Gulistan in the western frontiers, plus the unexpected death of ] in 1823, and the murdering of Persia's Grand ] (Mirza AbolQasem Qa'im Maqām), many Central Asian khanates began losing hope for any support from Persia against the ]ist armies.<ref>], ''Kharazm: What do I know about Iran?''. 2004. ISBN 964-379-023-1, p.78</ref> The Russian armies occupied the ] coast in 1849, ] in 1864, ] in 1867, ] in 1868, and ] and ] in 1873. | |||

| :''"Iran today is just a rump of what it once was. At its height, Iranian rulers controlled Iraq, Afghanistan, Western Pakistan, much of Central Asia, and the Caucasus. Many Iranians today consider these areas part of a greater Iranian sphere of influence."'' - ]<ref>]. ''Eternal Iran''. Palgrave. 2005. Coauthored with ]. {{ISBN|978-1-4039-6276-8}} p.30</ref> | |||

| :''"Many Iranians consider their natural sphere of influence to extend beyond Iran's present borders. After all, Iran was once much larger. Portuguese forces seized islands and ports in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 19th century, the Russian Empire wrested from ]'s control what is today Armenia, ], and part of Georgia. Iranian elementary school texts teach about the Iranian roots not only of cities like ], but also cities further north like ] in southern Russia. The ] lost much of his claim to western Afghanistan following the Anglo-Iranian war of 1856-1857. Only in 1970 did a ] sponsored consultation end Iranian claims to ] over the ] island nation of ]. In centuries past, Iranian rule once stretched westward into modern Iraq and beyond. When the western world complains of Iranian interference beyond its borders, the Iranian government often convinced itself that it is merely exerting its influence in lands that were once its own. Simultaneously, Iran's losses at the hands of outside powers have contributed to a sense of grievance that continues to the present day."'' -] of the ]<ref>]. ''Eternal Iran''. Palgrave. 2005. Coauthored with ]. ISBN 1-4039-6276-6 p.9,10</ref> | |||

| :''" |

:''"Since the days of the ], the Iranians had the protection of geography. But high mountains and the vast emptiness of the Iranian plateau were no longer enough to shield Iran from the Russian army or British navy. Both literally, and figuratively, Iran shrank. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Afghanistan were Iranian, but by the end of the century, all this territory had been lost as a result of European military action."''<ref>]. ''Eternal Iran''. Palgrave. 2005. Coauthored with ]. {{ISBN|978-1-4039-6276-8}} p.31-32</ref> | ||

| ==Regions== | |||

| :''"Since the days of the ], the Iranians had the protection of geography. But high mountains and vast emptiness of the Iranian plateau were no longer enough to shield Iran from the Russian army or British navy. Both literally, and figuratively, Iran shrank. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Afghanistan were Iranian, but by the end of the century, all this territory had been lost as a result of European military action."''<ref>]. ''Eternal Iran''. Palgrave. 2005. Coauthored with ]. ISBN 1-4039-6276-6 p.31-32</ref> | |||

| In the 8th century, Iran was conquered by the ] ] who ruled from ]. The territory of Iran at that time was composed of two portions: '']'' (western portion) and ''Khorasan'' (eastern portion). The dividing region was mostly the cities of ] and ]. The ], ] and ] divided their empires into Iraqi and Khorasani regions. This point can be observed in many books such as ]'s ''"Tārīkhi Baïhaqī"'', ]'s ''Faza'ilul al-anam min rasa'ili hujjat al-Islam'' and other books. Transoxiana and ] were mostly included in the Khorasanian region. | |||

| == |

===Caucasus=== | ||

| ====North Caucasus==== | |||

| In the ], the territory of Greater Iran was known to be composed of two portions: '']'' (western portion) and ''Khorasan'' (eastern portion). The dividing region was mostly along with ] and ] cities. Especially the ], ] and ] divided their ] to Iraqi and Khorasani regions. This point can be observed in many books such as ''"Tārīkhi Baïhaqī"'' of ], ''Faza'ilul al-anam min rasa'ili hujjat al-Islam'' (a collection of letters of ]) and other books. Transoxiana and ] were mostly included in the Khorasanian region. | |||

| {{See also|History of Dagestan|History of Kabardino-Balkaria|Russo-Persian Wars|Treaty of Gulistan|Treaty of Turkmenchay|Tat people (Caucasus)}} | |||

| ] fortress in ], Dagestan. Now inscribed on Russia's ] world heritage list since 2003.]] | |||

| ===Middle East=== | |||

| ====Iraq==== | |||

| {{See also|Iran–Iraq relations}} | |||

| ] in ], ], constructed between the 3rd and 6th centuries. It is the largest ] ever constructed in Persia and the world's largest single-span freestanding ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Scarre|first=Christopher|authorlink=Chris Scarre|title=The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World: The Great Monuments and How They Were Built|year=1999|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-500-05096-5|pages=185–186}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Andrade|first=Dale|title=Surging South of Baghdad: The 3rd Infantry Division|year=2010|publisher=Diane Publishing|isbn=978-1-4379-8119-3|page=39}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] has formed an intrinsic part of the Iranian world for most of the last three millennia. It is where the ] capital ], and the ] and ] capital ] were located. | |||

| Dagestan remains the bastion of ] in the ] with fine examples of Iranian architecture like the Sassanid citadel in ], the strong influence of ], and common Persian names amongst the ethnic peoples of Dagestan. The ethnic Persian population of the North Caucasus, the ], remain, despite strong assimilation over the years, still visible in several North Caucasian cities. Even today, after decades of partition, some of these regions retain Iranian influences, as seen in their old beliefs, traditions and customs (e.g. ]).<ref>'']'': "Caucasus Iran" article, p.84-96.</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|According to ] documents, Persians distinguished two kinds of land within their empire: "Īrān", and "Anīrān" ("non-Īrān"). Iraq was considered to be part of Īrān .<ref name=CB>{{cite book|last=Buck|first=Christopher|title=Paradise And Paradigm: Key Symbols In Persian Christianity And The Baháí̕ Faith|year=1999|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-7914-4061-2|page=64}}</ref> | |||

| ====South Caucasus==== | |||

| As Wilhelm Eilers observes: "For the Sassanians, too ]], the lowlands of Iraq constituted the heart of their dominions". This shows that Iraq was not simply part of the Persian Empire—it was the heart of Persia.<ref name=CB/>}} | |||

| {{See also|Azerbaijani people|History of Azerbaijan|Tat people (Iran)|Tat people (Caucasus)|Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam|Old Azeri language|Shirvan|Arran (Caucasus)|Shirvanshah|Iranian Azerbaijanis}} | |||

| According to ], the territories of ] and the republic of ] usually shared the same history from the time of ancient Media (ninth to seventh centuries b.c.) and the Persian Empire (sixth to fourth centuries b.c.).<ref>Historical Background Vol. 3, Colliers Encyclopedia CD-ROM, 02-28-1996</ref>{{page needed |date=September 2023}} | |||

| During the time of the ], from the 3rd century to the 7th century, the major part of Iraq was called in Persian ''Del-e Īrānshahr'' (lit. "the heart of Iran"), and its metropolis ] (not far from present-day ]) functioned for more than 800 years as the capital city of Iran.<ref>{{cite book|last=Marcinkowski|first=Christoph|title=Shi'ite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts|year=2010|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-643-80049-7|page=83|quote=During the time of the Sasanids, Iran's last dynasty before the arrival of Islam in the 7th century, the major part of Iraq was called in Persian ''Del-i Īrānshahr'' (lit. 'heart of Iran'), and its metropolis ] (not far from present-day ]) functioned for more than 800 years as the capital city of Iran.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Yavari|first=Neguin|title=Iranian Perspectives on the Iran-Iraq War; Part II. Conceptual Dimensions; 7. National, Ethnic, and Sectarian Issues in the Iran-Iraq War|year=1997|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-8130-1476-0|page=78|quote=Iraq with its capital of Ctesiphon was called by the Sasanian kings the 'heart of Iranshahr,' the land of Iran... The ruler spent most of the year in this capital, only moving to the cities of the highlands of Iran for the Summer.}}</ref> | |||

| Intimately and inseparably intertwined histories for millennia, Iran irrevocably lost the territory that is nowadays Azerbaijan in the course of the 19th century. With the ] of 1813 following the ] Iran had to cede eastern ], its possessions in the ] and many of those in what is today the ], which included the khanates of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and parts of ]. These Khanates comprise most of what is today the Republic of Azerbaijan and Dagestan in Southern Russia. In the ] of 1828 following the ], the result was even more disastrous, and resulted in Iran being forced to cede the remainder of the ], the khanates of ] and ], and the Mughan region to Russia. All these territories together, lost in 1813 and 1828 combined, constitute all of the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan, ], and southern ]. The area to the North of the river ], among which the territory of the contemporary republic of Azerbaijan were Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.<ref name="Swietochowski Borderland">{{cite book |last=Swietochowski|first=Tadeusz |author-link= Tadeusz Swietochowski |year=1995|title=Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition|pages= 69, 133 |publisher=] |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=FfRYRwAACAAJ&q=Russia+and+Iran+in+the+great+game:+travelogues+and+orientalism|isbn=978-0-231-07068-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=L. Batalden|first=Sandra |year=1997|title=The newly independent states of Eurasia: handbook of former Soviet republics|page= 98|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=WFjPAxhBEaEC&q=The+newly+independent+states+of+Eurasia:+handbook+of+former+Soviet+republics|isbn=978-0-89774-940-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first1=Robert E. |last1=Ebel |first2=Rajan |last2=Menon |year=2000|title=Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus|page= 181 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=-sCpf26vBZ0C&q=Energy+and+conflict+in+Central+Asia+and+the+Caucasus|isbn=978-0-7425-0063-1}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Andreeva|first=Elena |year=2010|title=Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism|page= 6 |edition= reprint |publisher=Taylor & Francis | url= https://books.google.com/books?id=FfRYRwAACAAJ&q=%3DRussia+and+Iran+in+the+great+game:+travelogues+and+orientalism|isbn=978-0-415-78153-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Çiçek, Kemal|first=Kuran, Ercüment |year=2000|title=The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation|publisher=University of Michigan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=c5VpAAAAMAAJ&q=The+Great+Ottoman-Turkish+Civilisation|isbn=978-975-6782-18-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Ernest Meyer, Karl|first=Blair Brysac, Shareen|year=2006|title=Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia|page=66|publisher=Basic Books|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ssv-GONnxTsC&q=Tournament+of+Shadows:+The+Great+Game+and+the+Race+for+Empire+in+Central+Asia|isbn=978-0-465-04576-1}}{{Dead link|date=May 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Of the four residences of the ] named by ] — ], ] or ], ] and ] — the last was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands.<ref name=EY>{{cite book|last=Yarshater|first=Ehsan|authorlink=Ehsan Yarshater|title=The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3|year=1993|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-521-20092-9|page=482|quote=Of the four residences of the ] named by ] — ], ] or ], ] and ] — the last was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands. Under the ] and the ] the site of the Mesopotamian capital moved a little to the north on the ] — to ] and ]. It is indeed symbolic that these new foundations were built from the bricks of ancient ], just as later ], a little further upstream, was built out of the ruins of the ] double city of ].}}</ref> | |||

| Many localities in this region bear Persian names or names derived from Iranian languages and Azerbaijan remains by far Iran's closest cultural, religious, ethnic, and historical neighbor. ] are by far the second-largest ethnicity in Iran, and comprise the largest community of ethnic Azerbaijanis in the world, vastly outnumbering the number in the Republic of Azerbaijan. Both nations are the only officially Shia majority in the world, with adherents of the religion comprising an absolute majority in both nations. The people of nowadays Iran and Azerbaijan were ] during exactly the same time in history. Furthermore, the name of "Azerbaijan" is derived through the name of the Persian ] which ruled the contemporary region of ] and minor parts of the Republic of Azerbaijan in ancient times.<ref>{{cite book |last=Houtsma|first=M. Th. |author-link=Martijn Theodoor Houtsma |year= 1993|title= First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936 |edition= reprint |publisher= BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-09796-4}}</ref><ref name="Schippmann">{{cite book |last=Schippmann|first=Klaus |year=1989 |title=Azerbaijan: Pre-Islamic History|pages= 221–224|publisher=Encyclopædia Iranica |isbn=978-0-933273-95-5}}</ref> | |||

| Under the ] and the ] the site of the Mesopotamian capital moved a little to the north on the ] — to ] and ]. It is indeed symbolic that these new foundations were built from the bricks of ancient ], just as later ], a little further upstream, was built out of the ruins of the ] double city of ].<ref name=EY/>|||Iranologist ]|The Cambridge History of Iran,<ref name=EY/>}} | |||

| ], written in ] ] in the name of the ] king, ]. It describes the Persian takeover of ] (the ancient name of Iraq).]] | |||

| Because the ] or "First Persian Empire" was the successor state to the empires of ] and ] based in Iraq, and because ] is part of Iran, the Iranians also share in the heritage of ancient ] together with the Iraqis. The ancient Persians adopted ] ] and ] to write their ], along with adopting many other facets of ancient Iraqi culture, including the ] which became the official language of the Persian Empire. | |||

| ===Central Asia=== | |||

| {{cquote|In 539 BC, the new Persian emperor, ], defeated the ]n army and entered ]. So attractive did Cyrus and his successors find Babylon that they made it the administrative ] of ]. More important, Cyrus attempted to bring about a synthesis of Persian and Iraqi culture. The quest for this synthesis laid the foundation for the great dilemma Iraqis face today.<ref name=IBT>{{cite book|last=Polk|first=William Roe|authorlink=William R. Polk|title=Understanding Iraq: A Whistlestop Tour from Ancient Babylon to Occupied Baghdad|year=2006|publisher=]|isbn=978-1-84511-123-6|pages=31–32|quote=In 539 BC, the new Persian emperor, ], defeated the ]n army and entered ]. So attractive did Cyrus and his successors find Babylon that they made it the administrative ] of ]. More important, Cyrus attempted to bring about a synthesis of Persian and Iraqi culture. The quest for this synthesis laid the foundation for the great dilemma Iraqis face today. One result of this quest was the Persian recasting of the ancient Iraqi tradition of gathering to recite or listen to ]. Precursors of these men had earlier narrated what we know as the Babylonian ]. In later but still ancient Iran, reciters repeated the ], the '']'', and sang "The Weeping of the ]".}}</ref> | |||

| ] head of a ] wearing a distinctive ]n-style headdress, ], ], ], 3rd-2nd century BCE.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Litvinskij |first1=B. A. |last2=Pichikian |first2=I. R. |year=1994 |title=The Hellenistic Architecture and Art of the Temple of the Oxus |journal=Bulletin of the Asia Institute |publisher=] |volume=8 |pages=47–66 |jstor=24048765 |issn=0890-4464}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] is one of the regions of ''Iran-zameen'', and is the home of the ancient Iranians, ], according to the ancient book of the ]. Modern scholars believe Khwarazm to be what ancient Avestic texts refer to as "Ariyaneh Waeje" or Iran vij. ''Iranovich'' These sources claim that ], which was the capital of ancient Khwarazm for many years, was actually "Ourva": the eighth land of ] mentioned in the ] text of Vendidad. Others such as ] historian ] believe Khwarazm to be the "most likely locale" corresponding to the original home of the Avestan people,<ref>], ''The History of Iran''. 2001. {{ISBN|978-0-313-30731-7}}, p.28</ref>{{Verify source|date=September 2023}} while Dehkhoda calls Khwarazm "the cradle of the ]n people" (مهد قوم آریا). Today Khwarazm is split between several central Asian republics. | |||

| One result of this quest was the Persian recasting of the ancient Iraqi tradition of gathering to recite or listen to ]. Precursors of these men had earlier narrated what we know as the Babylonian ] (''Enûma Eliš''). In later but still ancient Iran, reciters repeated the ], the '']'', and sang "The Weeping of the ]" (''Geristan-e-Moghan'').<ref name=IBT/>}} | |||

| Superimposed on and overlapping with Chorasmia was Khorasan which roughly covered nearly the same geographical areas in Central Asia (starting from ] eastward through northern Afghanistan roughly until the foothills of ], ancient ]). Current day provinces such as ] in ], ], ], and ] in Iran are all remnants of the old Khorasan. Until the 13th century and the devastating Mongol invasion of the region, Khorasan was considered the cultural capital of Greater Iran.<ref> | |||

| The ], written in ] ] in the name of the ] king ], describes the Persian takeover of Babylon (the ancient name of Iraq). An excerpt reads: | |||

| Lorentz, J. ''Historical Dictionary of Iran''. 1995. {{ISBN|978-0-8108-2994-7}}</ref>{{page needed |date=September 2023}} | |||

| ===China=== | |||

| {{cquote|When I entered Babylon in a peaceful manner, I took up my lordly abode in the royal palace amidst rejoicing and happiness. ], the great lord, established as his fate for me a ] heart of one who loves Babylon, and I daily attended to his worship. My vast army marched into Babylon in peace; I did not permit anyone to frighten the people of ]. I sought the welfare of the city of Babylon and all its sacred centers. As for the citizens of Babylon, upon whom ] imposed a ] which was not the gods' wish and not befitting them, I relieved their wariness and freed them from their service. Marduk, the great lord, rejoiced over my good deeds. He sent gracious blessing upon me, ], the king who worships him, and upon ], the son who is my offspring, and upon all my army, and in peace, before him, we moved around in friendship .}} | |||

| ====Xinjiang==== | |||

| {{See also|China–Iran relations|Tajiks of Xinjiang}} | |||

| {{Synthesis|date=December 2015}} | |||

| The ] regions of China harbored a Tajik population and culture.<ref>See '']'', p. 443, for Persian settlements in southwestern China; '']'' for more on the historical ties. | |||

| According to ] ]: {{cquote|Throughout Iran’s history the western part of the land has been frequently more closely connected with the ]s of Mesopotamia than with the rest of the ] to the east of the central deserts ] and ]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Frye|first=Richard N.|authorlink=Richard N. Frye|title=The Golden Age of Persia: The Arabs in the East|year=1975|publisher=Weidenfeld and Nicolson|isbn=978-0-7538-0944-0|page=184|quote= throughout Iran’s history the western part of the land has been frequently more closely connected with the ]s of Mesopotamia than with the rest of the ] to the east of the central deserts.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Yavari|first=Neguin|title=Iranian Perspectives on the Iran-Iraq War; Part II. Conceptual Dimensions; 7. National, Ethnic, and Sectarian Issues in the Iran-Iraq War|year=1997|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-8130-1476-0|page=80|quote=Between the coming of the 'Abbasids and the Mongol onslaught, Iraq and western Iran shared a closer history than did eastern Iran and its western counterpart.}}</ref>}} | |||

| </ref> Chinese Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County was always counted as a part of the Iranian cultural & linguistic continent with ], ], and ] bound to the Iranian history.<ref>"Persian language in ]" (زبان فارسی در سین کیانگ). Zamir Sa'dollah Zadeh (دکتر ضمیر سعدالله زاده). ''Nameh-i Iran'' (نامه ایران) V.1. Editor: Hamid Yazdan Parast (حمید یزدان پرست). {{ISBN|978-964-423-572-6}} ] collection under DS 266 N336 2005.</ref> | |||

| ===West Asia=== | |||

| The ] historian Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru (d. 1430) wrote of Iraq: | |||

| ====Bahrain==== | |||

| {{cquote|The majority of inhabitants of Iraq know ] and ], and from the time of domination of ] the ] has also found currency.<ref>{{cite web|last=Morony|first=Michael G|authorlink=Michael G. Morony|title=IRAQ AND ITS RELATIONS WITH IRAN|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iraq-i-late-sasanid-early-islamic|work=IRAQ i. IN THE LATE SASANID AND EARLY ISLAMIC ERAS|publisher=]|accessdate=11 February 2012|quote=Persian remained the language of most of the sedentary people as well as that of the chancery until the 15th century and thereafter, as attested by Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru (d. 1430) who said, “The majority of inhabitants of Iraq know Persian and Arabic, and from the time of domination of Turkic people the Turkish language has also found currency: as the city people and those engaged in trade and crafts are Persophone, the Bedouins are Arabophone, and the governing classes are Turkophone. But, all three peoples (qawms) know each other’s languages due to the mixture and amalgamation.”}}</ref>}} | |||

| {{See also|Ajam of Bahrain|Huwala people}} | |||

| ] in ], ] is one of ]'s ] and a place of great annual ].]] | |||

| ] share significant religious, cultural and ethnic ties with ]. Close to two-thirds of Iraqis adhere to ] ] – the same religion, sect, and school adhered to by most Iranians – and around one-fifth of Iraqis speak ]. Many Iraqis who speak ] are of ] origin, and Iranian surnames are common in Iraq. Many Iraqis hold elements of Persian identity, while still loving Iraq — a legacy of several millennia of ] and migration between the Iraqi lowland and the Iranian highland. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Iraqi culture has much in common with the ]. The spring festival of ] is celebrated in Iraq by Kurdish and Shī'i Iraqis. Indeed, a ] has been practised in Iraq since ]ian times. The ] is very similar to the ] and features many Persian dishes and cooking techniques. The ] has absorbed many words from the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Csató|first1=Éva Ágnes|last2=Isaksson|first2=Bo|last3=Jahani|first3=Carina|title=Linguistic Convergence and Areal Diffusion: Case Studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic|year=2005|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-415-30804-5|page=177}}</ref> | |||

| From the 6th century BC to the 3rd century BC, Bahrain was a prominent part of the Persian Empire under the ] dynasty. It was referred to by the Greeks as "]", the centre of ] trading, when ] discovered it while serving under ].<ref name="Larsen">''Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient ...'' by Curtis E. Larsen p. 13</ref> From the 3rd century BC to the arrival of Islam in the 7th century AD, the island was controlled by two other Iranian dynasties, the ] and the ]. | |||

| There are still cities and provinces in Iraq where the Persian names of the city are still retained. e.g. ] and ]. Other cities of Iraq with originally Persian names include ''Nokard'' (نوكرد) --> ], ''Suristan'' (سورستان) --> ], ''Shahrban'' (شهربان) --> ], ''Arvandrud'' (اروندرود) --> ], and ''Asheb'' (آشب) --> ].<ref>See: محمدی ملایری، محمد: فرهنگ ایران در دوران انتقال از عصر ساسانی به عصر اسلامی، جلد دوم: دل ایرانشهر، تهران، انتشارات توس 1375.: Mohammadi Malayeri, M.: Del-e Iranshahr, vol. II, Tehran 1375 Hs.</ref> | |||

| In the 3rd century AD, the Sassanids succeeded the Parthians and controlled the area for four centuries until the Arab conquest.<ref name="Federal Research Division page 7"/> ], the first ruler of the Iranian Sassanid dynasty marched to Oman and Bahrain and defeated Sanatruq<ref>Robert G. Hoyland, ''Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam'', Routledge 2001p28</ref> (or Satiran<ref name="Mojtahed-Zadeh">''Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography'' by Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, page 119</ref>), probably the Parthian governor of Bahrain.<ref name = "Jamsheed"/> He appointed his son ] as governor. Shapur constructed a new city there and named it Batan Ardashir after his father.<ref name="Mojtahed-Zadeh"/> At this time, it incorporated the southern Sassanid province covering the Persian Gulf's southern shore plus the archipelago of Bahrain.<ref name="Jamsheed">Conflict and Cooperation: Zoroastrian Subalterns and Muslim Elites in ... By Jamsheed K. Choksy, 1997, page 75</ref> The southern province of the Sassanids was subdivided into three districts; Haggar (now al-Hafuf province, Saudi Arabia), Batan Ardashir (now ] province, Saudi Arabia), and ] (now Bahrain Island)<ref name="Mojtahed-Zadeh"/> (In ]/Pahlavi it means "ewe-fish").<ref>Yoma 77a and Rosh Hashbanah, 23a</ref> | |||

| In the modern era, the ] of Iran briefly asserted their hegemony over Iraq in the periods of ] and ], losing Iraq to the ] on both occasions (via the ] in 1555 and the ] in 1639). Ottoman hegemony over Iraq was reconfirmed in the ] in 1746. | |||

| ] at their greatest extent]] | |||

| By about 130 BC, the Parthian dynasty brought the Persian Gulf under their control and extended their influence as far as ]. Because they needed to control the Persian Gulf trade route, the Parthians established garrisons along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf.<ref name="Federal Research Division page 7">''Bahrain'' by Federal Research Division, page 7</ref> | |||

| through warfare and economic distress, been reduced to only 60.<ref>Juan Cole, ''Sacred Space and Holy War'', IB Tauris, 2007 p52</ref> | |||

| The influence of Iran was further undermined at the end of the 18th century when the ideological power struggle between the Akhbari-Usuli strands culminated in victory for the Usulis in Bahrain.<ref> Maximilian Terhalle, ''Middle East Policy'', Volume 14 Issue 2 Page 73, June 2007</ref> | |||

| An Afghan uprising led by Hotakis of Kandahar at the beginning of the 18th century resulted in the near-collapse of the Safavid state.{{CN|date=May 2023}} In the resultant power vacuum, ], ending over one hundred years of Persian hegemony in Bahrain. The Omani invasion began a period of political instability and a quick succession of outside rulers took power with consequent destruction. According to a contemporary account by theologian, Sheikh Yusuf Al Bahrani, in an unsuccessful attempt by the Persians and their Bedouin allies to take back Bahrain from the ] Omanis, much of the country was burnt to the ground.<ref> published in ''Interpreting the Self, Autobiography in the Arabic Literary Tradition'', Edited by Dwight F. Reynolds, University of California Press Berkeley 2001</ref> Bahrain was eventually sold back to the Persians by the Omanis, but the weakness of the Safavid empire saw ] tribes seize control.<ref>The Autobiography of Yūsuf al-Bahrānī (1696–1772) from Lu'lu'at al-Baḥrayn, from the final chapter featured in ''Interpreting the Self, Autobiography in the Arabic Literary Tradition'', Edited by Dwight F. Reynolds, University of California Press Berkeley 2001 p221</ref> | |||

| When the ] was formed in 1921 by the ], the ]n government refused to recognize the state, claiming ] and ] as "holy places of ]".<ref>{{cite book|last=Anderson|first=Terry H.|authorlink=Terry H. Anderson|title=Bush's Wars|year=2011|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-19-974752-8|page=12}}</ref> During the four-decade-long British occupation of Iraq, the British sought to reduce Persian influence in the country<ref>{{cite book|last=Nakash|first=Yitzhak|title=The Shi'is of Iraq|year=2003|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-691-11575-7|pages=100–102}}</ref> – a policy continued under the later ] ] which came to power through a ] in 1963. Following the fall of the Ba'athist regime in 2003 and the empowerment of Iraq's majority Shī'i community, relations with Iran have flourished in all fields. Iraq is today one of Iran's largest trading partners. | |||

| ] under ]]] | |||

| In 1730, the new Shah of ], ], sought to re-assert Persian sovereignty in Bahrain. He ordered Latif Khan, the admiral of the Persian navy in the Persian Gulf, to prepare an invasion fleet in ].{{CN|date=May 2023}} The Persians invaded in March or early April 1736 when the ruler of Bahrain, Shaikh Jubayr, was away on ].{{CN|date=May 2023}} The invasion brought the island back under central rule and to challenge Oman in the Persian Gulf. He sought help from the British and Dutch, and he eventually recaptured Bahrain in 1736.<ref>Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p19</ref> During the ] era, Persian control over Bahrain waned{{CN|date=May 2023}} and in 1753, Bahrain was occupied by the Sunni Persians of the ]-based Al Madhkur family,<ref>Ahmad Mustafa Abu Hakim, ''History of Eastern Arabia 1750–1800'', Khayat, 1960, p78</ref><!--unreliable source--> who ruled Bahrain in the name of Persia and paid allegiance to ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| During most of the second half of the eighteenth century, Bahrain was ruled by ], the ruler of ]. The Bani Utibah tribe from Zubarah exceeded in taking over Bahrain after war broke out in 1782. Persian attempts to reconquer the island in 1783 and in 1785 failed; the 1783 expedition was a joint Persian-] invasion force that never left Bushehr. The 1785 invasion fleet, composed of forces from Bushehr, Rig, and ] was called off after the death of the ruler of Shiraz, ]. Due to internal difficulties, the Persians could not attempt another invasion.{{CN|date=May 2023}} In 1799, Bahrain came under threat from the ] policies of ], the ], when he invaded the island under the pretext that Bahrain did not pay taxes owed.{{CN|date=May 2023}} The Bani Utbah solicited the aid of Bushire to expel the Omanis on the condition that Bahrain would become a ] of Persia. In 1800, Sayyid Sultan invaded Bahrain again in retaliation and deployed a garrison at ], in ] island and had appointed his twelve-year-old son Salim, as Governor of the island.<ref>James Onley, The Politics of Protection in the Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century, Exeter University, 2004 p44</ref> | |||

| ] at its greatest extent]] | |||

| Many names of villages in Bahrain are derived from the ] language.<ref name=Tajer>{{cite book|last=Al-Tajer|first=Mahdi Abdulla|title=Language & Linguistic Origins In Bahrain|year=1982|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-0-7103-0024-9|pages=134, 135|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BNs9AAAAIAAJ&q=bahrain%20village%20persian%20name&pg=PA134}}</ref> These names were thought to have been as a result influences during the ] rule of Bahrain (1501–1722) and previous Persian rule. Village names such as ], ], ], ], ] were originally derived from the Persian language, suggesting that Persians had a substantial effect on the island's history.<ref name=Tajer/> The local ] dialect has also borrowed many words from the Persian language.<ref name=Tajer/> Bahrain's capital city, ] is derived from two Persian words meaning 'I' and 'speech'.<ref name=Tajer/>{{contradict-inline|article=Manama|section=Etymology|date=March 2018}} | |||

| In 1910, the Persian community funded and opened a ], Al-Ittihad school, that taught ] amongst other subjects.<ref>{{cite book|last=Shirawi|first=May Al-Arrayed|title=Education in Bahrain - 1919-1986, An Analytical Study of Problems and Progress|url=http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6662/1/6662_3966.PDF?UkUDh:CyT|year=1987|publisher=Durham University|page=60}}</ref> | |||

| Many Iranians were born in Iraq or have ancestors from Iraq, such as the ] ], the former ] ], and the ] ], who were born in ] and ] respectively. In the same way, many Iraqis were born in Iran or have ancestors from Iran, such as ] ], who was born in ]. | |||

| According to the 1905 census, there were 1650 Bahraini citizens of Persian origin.<ref name=pol/> | |||

| Historian Nasser Hussain says that many Iranians fled their native country in the early 20th century due to a law king ] issued which banned women from wearing the ], or because they feared for their lives after fighting the English or to find jobs. They were coming to Bahrain from Bushehr and the ] between 1920 and 1940. In the 1920s, local Persian merchants were prominently involved in the consolidation of Bahrain's first powerful lobby with connections to the municipality in an effort to contest the municipal legislation of British control.<ref name=pol>{{cite book|last=Fuccaro|first=Nelida|title=Histories of City and State in the Persian Gulf: Manama Since 1800|page=114|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wKU6jvKGicUC|isbn=978-0-521-51435-4|date=2009-09-03|publisher=Cambridge University Press }}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Every soul that has ] in Iraq, is as if an Iranian has fallen.|||], ]|<ref>{{cite web|title=A conversation with Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, President of the Islamic Republic of Iran|url=http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/10611|publisher=]|accessdate=11 February 2012}}</ref>}} | |||

| Bahrain's local Persian community has heavily influenced the country's local food dishes. One of the most notable local delicacies of the people in Bahrain is '']'', which is consumed in Southern Iran as well. It is a watery, earth-brick-coloured sauce made from sardines, and consumed with bread or other food. Bahrain's Persians are also famous in Bahrain for bread-making. Another local delicacy is ''pishoo'' made from ] (''golab'') and ]. Other food items consumed are similar to ]. | |||

| ====Kurdistan==== | |||

| Culturally and historically ] has been part of what is known as Greater Iran. Kurds who speak a Northwestern Iranian language known as Kurdish comprise the majority of the population of the region there are also communities of Arab, Armenian, Assyrian, Azeri, Jewish, Persian, and Turkic people traditionally scattered throughout the region. Most of its inhabitants are Muslim, but there are also significant numbers of other religious sects such as Yazidi, Yarsan, Alevi, Christian, Kurdish Jews, and a modern revival of interest in Zoroastrianism, though the last of these is largely, if not entirely, nominal. | |||

| === |

====Iraq==== | ||

| {{See also|Iran–Iraq relations|Iran–Iraq War|Persians in Iraq|Asuristan}} | |||

| ====Armenia==== | |||

| {{See also|Persian Armenia|Iranian Armenians}} | |||

| ] was a province of various Persian Empires since the Achaemenid period and was heavily influenced by Persian culture. Armenia however, has historically been largely populated by a distinct ]-speaking people who merged with local ] peoples, rather than being directly associated with the Iranian peoples. Ancient Armenian society was a combination of local cultures, Iranian social and political structures, and ]/] traditions.<ref>See: | |||

| *Link: | |||

| *] p.417-483 for a lengthy discussion on this topic. Link: </ref> Due to centuries of independent indigenous development, conquests by western powers including the ] and Russians, and its diverse diasporic population that has absorbed many cultural traits, especially those of Europe and ]. | |||

| Throughout history, Iran always had strong cultural ties with the region of present-day ]. ] is considered the cradle of civilization and the place where the first empires in history were established. These empires, namely the ]ian, ], ]n, and ]n, dominated the ancient middle east for millennia, which explains the great influence of Mesopotamia on the Iranian culture and history, and it is also the reason why the later Iranian and Greek dynasties chose Mesopotamia to be the political center of their rule. For a period of around 500 years, what is now Iraq formed the core of Iran, with the Iranian ] and ] empire having their capital in what is modern-day Iraq for the same centuries-long time span. (]) | |||

| Iran continues to have a ] that links ] to Iranian culture. Many Armenians such as ] were directly involved and remembered in the History of Iran. | |||

| {{cquote|Of the four residences of the ] named by ]—], ] or ], ] and ]—the last was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands.<ref name=EY>{{cite book|last=Yarshater|first=Ehsan|author-link=Ehsan Yarshater|title=The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3|year=1993|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-521-20092-9|page=482|quote=Of the four residences of the Achaemenids named by ]—], ] or ], ] and ]—the last was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands. Under the ] and the ] the site of the Mesopotamian capital moved a little to the north on the ]—to ] and ]. It is indeed symbolic that these new foundations were built from the bricks of ancient ], just as later ], a little further upstream, was built out of the ruins of the ] double city of ].}}</ref> | |||

| ====Azerbaijan==== | |||

| With the Treaty of Gulistan, Iran had to cede all the Khanates of the ], which included ], ], ], ], ], ], and parts of the ]. Derbent (Darband) was also lost to Russia. These Khanates comprise what is today the Republic of Azerbaijan. By the Treaty of Turkmenchay, Iran was forced to cede ] and the Mughan regions to Russia, as well as ]. These territories roughly constitute the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan and ]. Most localities in this region bear Persian names or names derived from Iranian languages. | |||

| Under the ] and the ] the site of the Mesopotamian capital moved a little to the north on the ]—to ] and ]. It is indeed symbolic that these new foundations were built from the bricks of ancient ], just as later ], a little further upstream, was built out of the ruins of the ] double city of ].<ref name=EY />|||Iranologist ]|The Cambridge History of Iran,<ref name=EY />}} | |||

| ====Georgia==== | |||

| ]. Painting is located at Berlin's Museum Für Islamische Kunst.]] | |||

| The eastern ] regions of ] and ] were Persian Provinces during Sassanid times (particularly starting with Hormozd IV). Some members of the Georgian elite were involved in the Safavid government and ], ], was the son of a Georgian father.<ref>Patrick Clawson. Eternal Iran. Palgrave. 2005. Coauthored with Michael Rubin. ISBN 1-4039-6276-6 p.168</ref> | |||

| ], written in ] ] in the name of the ] king, ], describes the Persian takeover of ] (An ancient city in modern-day Iraq).]] | |||

| Eastern Georgia was under the influence of Persia until 1783 when ] of ] signed the ] with the Russian Empire. Persia officially gave up claim to parts of Georgia according to the terms of the Gulistan and Turkmenchay Treaties. | |||

| ] at time of ]]] | |||

| ====Nakhchivan==== | |||

| According to ] ]:<ref>{{cite book|last=Frye|first=Richard N.|author-link=Richard N. Frye|title=The Golden Age of Persia: The Arabs in the East|year=1975|publisher=Weidenfeld and Nicolson|isbn=978-0-7538-0944-0|page=184|quote= throughout Iran's history the western part of the land has been frequently more closely connected with the lowlands of Mesopotamia than with the rest of the plateau to the east of the central deserts.}}</ref><ref name=NY>{{cite book|last=Yavari|first=Neguin|title=Iranian Perspectives on the Iran-Iraq War; Part II. Conceptual Dimensions; 7. National, Ethnic, and Sectarian Issues in the Iran–Iraq War|year=1997|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-8130-1476-0|page=80|quote=Between the coming of the 'Abbasids and the Mongol onslaught, Iraq and western Iran shared a closer history than did eastern Iran and its western counterpart.}}</ref> | |||

| Early in antiquity, ] is known to have had fortifications built here. In later times, some of Persia's literary and intellectual figures from the ] period have hailed from this region. Also separated from Greater-Iran/Persia in the mid-19th century, by virtue of the Gulistan Treaty and Turkmenchay Treaty. | |||

| {{quote|Throughout Iran's history the western part of the land has been frequently more closely connected with the ]s of Mesopotamia (Iraq) than with the rest of the ] to the east of the central deserts ] and ]]. | Richard N. Frye | ''The Golden Age of Persia: The Arabs in the East''}} | |||

| که تا جایگه یافتی نخچوان<br /> | |||

| Oh ], respect you've attained,<br /> | |||

| بدین شاه شد بخت پیرت جوان<br /> | |||

| With this King in luck you'll remain.<br /> | |||

| ''---]'' | |||

| {{Rquote|right|Between the coming of the Abbasids and the Mongol onslaught , Iraq and western Iran shared a closer history than did eastern Iran and its western counterpart. | Neguin Yavari | ''Iranian Perspectives on the Iran–Iraq War''<ref name=NY />}} | |||

| ====North Caucasus==== | |||

| {{See also|Russo-Persian Wars|Treaty of Gulistan|Treaty of Turkmenchay}} | |||

| ] region in today's southern ] including the republics of ], ], ], ] and other republics and oblasts of the region long formed part of Persia and the Iranian cultural sphere until they were annexed by Imperial Russia over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries. Strong Persian cultural influence can be traced up as far as ] in central Russia. Fine examples of Iranian architecture in many Caucasus cities like the Sassanid citadel in ] bear witness to the importance of these territories before the arrival of Russians to the region, when it was under Persian influence, rule and suzerainty. (Even today, after decades of partition, some of these regions retain a sort of Iranian identity, as seen in their old beliefs, traditions and customs (e.g. ])).<ref>'']'': "Caucasus Iran" article, p.84-96.</ref> | |||

| Testimony to the close relationship shared by Iraq and western Iran during the ] and later centuries, is the fact that the two regions came to share the same name. The western region of ] (ancient Media) was called ] ("Persian Iraq"), while central-southern ] (Babylonia) was called 'Irāq al-'Arabī ("Arabic Iraq") or Bābil ("Babylon"). | |||

| ===Central Asia=== | |||

| ] is one of the regions of ''Iran-zameen'', and is the home of the ancient Iranians, ], according to the ancient book of the ]. Modern scholars believe Khwarazm to be what ancient Avestic texts refer to as "Ariyaneh Waeje" or Iran vij. ''Iranovich'' These sources claim that ], which was the capital of ancient Khwarazm for many years, was actually "Ourva": the eighth land of ] mentioned in the ] text of Vendidad. Others such as ] historian ] believe Khwarazm to be the "most likely locale" corresponding to the original home of the Avestan people,<ref>], ''The History of Iran''. 2001. ISBN 0-313-30731-8, p.28</ref> while Dehkhoda calls Khwarazm "the cradle of the ]n tribe" (مهد قوم آریا). Today Khwarazm is split between several central Asian republics. | |||

| For centuries the two neighbouring regions were known as "]" ("al-'Iraqain"). The 12th century Persian poet ] wrote a famous poem ''Tohfat-ul Iraqein'' ("The Gift of the Two Iraqs"). The city of ] in western Iran still bears the region's old name, and Iranians still traditionally call the region between ], ] and ] "ʿErāq". | |||

| Superimposed on and overlapping with Chorasmia was Khorasan which roughly covered nearly the same geographical areas in Central Asia (starting from ] eastward through northern Afghanistan roughly until the foothills of ], ancient ]). Current day provinces such as ] in ], ], ], and ] in Iran are all remnants of the old Khorasan. Until the 13th century and the devastating Mongol invasion of the region, Khorasan was considered the cultural capital of Greater Iran.<ref> | |||

| Lorentz, J. ''Historical Dictionary of Iran''. 1995. ISBN 0-8108-2994-0</ref> | |||

| During the medieval ages, Mesopotamian and Iranian peoples knew each other's languages because of trade, and because Arabic was the language of religion and science at that time. The ] historian ] (d. 1430) wrote of Iraq:<ref>{{cite web|last=Morony|first=Michael G|author-link=Michael G. Morony|title=IRAQ AND ITS RELATIONS WITH IRAN|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iraq-i-late-sasanid-early-islamic|work=IRAQ i. IN THE LATE SASANID AND EARLY ISLAMIC ERAS|publisher=]|access-date=11 February 2012|quote=Persian remained the language of most of the sedentary people as well as that of the chancery until the 15th century and thereafter, as attested by Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru (d. 1430) who said, "The majority of inhabitants of Iraq know Persian and Arabic, and from the time of the domination of Turkic people the Turkish language has also found currency: as the city people and those engaged in trade and crafts are Persophone, the Bedouins are Arabophone, and the governing classes are Turkophone. But, all three peoples (qawms) know each other's languages due to the mixture and amalgamation."}}</ref> | |||

| ====Afghanistan==== | |||

| {{quote|The majority of inhabitants of Iraq know ] and ], and from the time of the domination of ] the ] has also found currency. | Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru}} | |||