| Revision as of 22:05, 19 March 2007 editDsp13 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Pending changes reviewers103,593 edits →Audio / Video: reordered (defaultsort with categories)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:01, 3 January 2025 edit undoKMaster888 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users11,371 edits remove promotional content | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Russian-born American author and philosopher (1905–1982)}} | |||

| {{sprotect}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Infobox Writer | |||

| {{Use American English|date=February 2023}} | |||

| | name = Ayn Rand | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2023}} | |||

| | image = Ayn_Rand1.jpg | |||

| {{Infobox writer | |||

| | imagesize = 150px | |||

| | name = Ayn Rand | |||

| | birth_date = ], ] | |||

| | native_name = Алиса Зиновьевна Розенбаум | |||

| | birth_place = ] | |||

| | image = Ayn Rand (1943 Talbot portrait).jpg | |||

| | death_date = ], ] | |||

| | alt = Photo of Ayn Rand | |||

| | death_place = ] | |||

| | caption = Rand in 1943 | |||

| | occupation = novelist, philosopher, playwright, screenwriter | |||

| | birth_name = Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum | |||

| | magnum_opus = '']'' | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1905|02|02}} | |||

| | influences = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | influenced = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], many others | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1982|3|6|1905|2|2}} | |||

| | death_place = New York City, U.S.<!-- DO NOT REMOVE the country per ] --> | |||

| | pseudonym = Ayn Rand | |||

| | occupation = {{hlist|Author|philosopher}} | |||

| | language = {{cslist|English|Russian}} | |||

| | citizenship = {{ublist| | |||

| | Russia (until 1931){{efn|Rand's initial citizenship was in the ] and continued through the ] and the ], which became part of the ].}} | |||

| | United States (from 1931)}} | |||

| | alma_mater = ] | |||

| | period = 1934–1982 | |||

| | notableworks = ] | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|1929|1979|end=d}}{{efn|name="frank"|Rand's husband, Charles Francis O'Connor (1897–1979),{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=65}} is not to be confused with the actor and director ] (1881–1959) or the writer whose pen name was ].}} | |||

| | signature = Ayn Rand signature 1949.svg | |||

| | signature_alt = Ayn Rand | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Ayn Rand''' ({{IPA2|aɪn ɹænd}}, {{OldStyleDate|February 2|1905|January 20}} – ] ]), born '''Alisa Zinov'yevna Rosenbaum''' ({{lang-ru|Алиса Зиновьевна Розенбаум}}), was a ]n-born ] novelist and philosopher,<ref>One source notes: "Perhaps because she so eschewed academic philosophy, and because her works are rightly considered to be works of literature, Objectivist philosophy is regularly omitted from academic philosophy. Yet throughout literary academia, Ayn Rand is considered a philosopher. Her works merit consideration as works of philosophy in their own right." (Jenny Heyl, 1995, as cited in {{cite book|title=Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand|editor=Mimi R Gladstein, Chris Matthew Sciabarra(eds)|id=ISBN 0-271-01831-3|publisher=Penn State Press|year=1999}}, )</ref> best known for developing ] and for writing the novels ''],'' ''],'' '']'' and the ] ''].'' <br />She was a broadly influential figure in post-WWII America, her work attracting both enthusiastic admiration and scathing denunciations. | |||

| '''Alice O'Connor''' (born '''Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum''';{{efn|{{langx|ru|link=no|Алиса Зиновьевна Розенбаум}}, {{IPA|ru|ɐˈlʲisə zʲɪˈnovʲjɪvnə rəzʲɪnˈbaʊm|}}. Most sources ] her given name as either ''Alisa'' or ''Alissa''.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=121}}}} {{OldStyleDateNY|February 2|January 20}}, 1905{{dash}}March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name '''Ayn Rand''' ({{IPAc-en|aɪ|n}}), was a Russian-born American author and philosopher.<!-- DO NOT REMOVE WITHOUT CONSENSUS. -->{{sfn|Badhwar|Long|2020}} She is known for her fiction and for developing a philosophical system she named ]. Born and educated in Russia, she moved to the United States in 1926. After two early novels that were initially unsuccessful and two ] plays, Rand achieved fame with her 1943 novel '']''. In 1957, she published her best-selling work, the novel '']''. Afterward, until her death in 1982, she turned to non-fiction to promote her philosophy, publishing her own ] and releasing several collections of essays. | |||

| ==Introduction== | |||

| Rand advocated ] and rejected ] and religion. She supported ] and ] as opposed to ] and ]. In politics, she condemned the ] as immoral and supported ], which she defined as the system based on recognizing ], including ] rights. Although she opposed ], which she viewed as ], Rand is often associated with the modern ]. In art, she promoted ]. She was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her, with a few exceptions. | |||

| Rand's writing (both fiction and non-fiction) emphasizes the philosophic concepts of ] in ], ] in ], and ] in ethics. In politics she was a proponent of ] and a staunch defender of ], believing that the sole function of a proper government was protection of the individual's right to his life, liberty, and property. | |||

| Rand's books have sold over 37 million copies. Her fiction received mixed reviews from literary critics, with reviews becoming more negative for her later work.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|pp=117–119}} Although academic interest in her ideas has grown since her death,{{sfn|Cocks|2020|p=15}} academic philosophers have generally ignored or rejected Rand's philosophy, arguing that she has a polemical approach and that her work lacks methodological rigor.{{sfn|Badhwar|Long|2020}} Her writings have politically influenced some ] and ]. The ] circulates her ideas, both to the public and in academic settings. | |||

| She believed that individuals must choose their values and actions solely by reason, and that "Man — every man — is an end in himself, not the means to the ends of others." According to Rand, the individual "must exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself. The pursuit of his own rational self-interest and of his own happiness is the highest moral purpose of his life." | |||

| == Life == | |||

| Rand decried the initiation of force (considering fraud to be a covert initiation of force), and held that government action should consist only in protecting citizens from criminal behavior (via the police) and foreign hostility (via the military) and in maintaining a system of courts to decide guilt or innocence and to objectively resolve disputes. Her politics are generally described as ] and ], though she did not use the first term and disavowed any connection to the second.<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.aynrand.org/site/PageServer?pagename=education_campus_libertarians|title="Ayn Rand's Q&A on Libertarians."|accessdate=2006-03-22}} at the ]. Rand stated in 1980, "I’ve read nothing by a Libertarian...that wasn’t my ideas badly mishandled — i.e., had the teeth pulled out of them — with no credit given."</ref> | |||

| === Early life === | |||

| Rand was born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum on February{{nbs}}2, 1905, into a Jewish ] family living in ] in what was then the ].{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=xiii}} She was the eldest of three daughters of Zinovy Zakharovich Rosenbaum, a pharmacist, and Anna Borisovna ({{née|Kaplan}}).{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=3–5}} She was 12 when the ] and the rule of the ] under ] disrupted her family's lives. Her father's pharmacy was nationalized,{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=31}} and the family fled to ] in Crimea, which was initially under the control of the ] during the ].{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=35}} After graduating high school there in June 1921,{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=36}} she returned with her family to Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg was then named),{{efn|The city was renamed ''Petrograd'' from the Germanic ''Saint Petersburg'' in 1914 because Russia was at war with Germany. In 1924 it was renamed ''Leningrad''. The name ''Saint Petersburg'' was restored in 1991.{{sfn|Ioffe|2022}}}} where they faced desperate conditions, occasionally nearly starving.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|pp=86–87}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Rand, a self-described hero-worshiper, stated in her book ''Romantic Manifesto'' that the goal of her writing was "the projection of an ideal man." In reference to her philosophy, ], she said: "My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute." (Appendix to '']'') | |||

| When Russian universities were opened to women after the revolution, Rand was among the first to enroll at ].{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=15}} At 16, she began her studies in the department of ], majoring in history.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=72}} She was one of many bourgeois students purged from the university shortly before graduating. After complaints from a group of visiting foreign scientists, many purged students, including Rand, were reinstated.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=47}}{{sfn|Britting|2004|p=24}} She graduated from the renamed Leningrad State University in October 1924.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=15}}{{sfn|Sciabarra|1999|p=1}} She then studied for a year at the State ] for Screen Arts in Leningrad. For an assignment, Rand wrote an essay about the Polish actress ]; it became her first published work.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=49–50}} She decided her professional surname for writing would be ''Rand'',{{sfn|Britting|2004|p=33}} and she adopted the first name ''Ayn'' (pronounced {{IPAc-en|aɪ|n}}).{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=9}}{{efn|She may have taken ''Rand'' as her surname because it is graphically similar to a vowelless excerpt {{lang|ru|Рзнб}} of her birth surname {{lang|ru|Розенбаум}} in ].{{sfn|Gladstein|2010|p=7}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=55}} Rand said ''Ayn'' was adapted from a ] name.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=19, 301}} Some biographical sources question this, suggesting it may come from a nickname based on the Hebrew word {{lang|he| עין}} ('']'', meaning 'eye').{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=55–57}} Letters from Rand's family do not use such a nickname.<ref>Milgram, Shoshana. "The Life of Ayn Rand: Writing, Reading, and Related Life Events". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=39}}.</ref>}} | |||

| In late 1925, Rand was granted a ] to visit relatives in Chicago.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=18–19}} She arrived in New York City on February{{nbs}}19, 1926.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=53}} Intent on staying in the United States to become a screenwriter, she lived for a few months with her relatives learning English{{sfn|Hicks}} before moving to ], California.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=57–60}} | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| ===Childhood and education=== | |||

| Rand was born in ], ], and was the eldest of three daughters (Alisa, Natasha, and Nora)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.asenseoflife.com/synopsis.html|title=''A Sense of Life''|accessdate=2006-03-22}} website of the documentary film about Rand's life.</ref> of a ]ish family. Her parents, Zinovny Zacharovich Rosenbaum and Anna Borisovna Rosenbaum, were ] and largely non-observant.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sciabarra/rad/PubRadReviews/fc1.html|title="Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical - Published Reviews."|accessdate=2006-03-23}}</ref> From an early age, she displayed an interest in literature and films. She started writing screenplays and novels at the age of seven. | |||

| In Hollywood a chance meeting with director ] led to work as an ] in his film '']'' and a subsequent job as a junior screenwriter.{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=34–36}} While working on ''The King of Kings'', she met the aspiring actor ];{{efn|name="frank"}} they married on April{{nbs}}15, 1929. She became a ] in July 1929 and an ] on March{{nbs}}3, 1931.{{sfn|Britting|2004|p=39}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=71}}{{efn|Rand's immigration papers ] her given name as ''Alice'';{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=53}} her legal married name became ''Alice O'Connor'', but she did not use that name publicly or with friends.<ref>Milgram, Shoshana. "The Life of Ayn Rand: Writing, Reading, and Related Life Events". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=24}}.</ref>{{sfn|Branden|1986|p=72}}}} She tried to bring her parents and sisters to the United States, but they could not obtain permission to emigrate.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=96–98}}{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=43–44, 52}} Rand's father died of a heart attack in 1939; one of her sisters and their mother died during the ].{{sfn|Popoff|2024|p=119}} | |||

| Her mother taught her French and subscribed to a magazine featuring stories for boys, where Rand found her first childhood hero: Cyrus Paltons, an Indian army officer in a ]-style story by ], called "The Mysterious Valley".<ref name="Chronology">{{cite web|title="Ayn Rand Chronology"|url=http://www.atlassociety.org/rand_chronology.asp|accessdate=2006-03-23}}</ref> Throughout her youth, she read the novels of ], ] and other Romantic writers, and expressed a passionate enthusiasm toward the ] as a whole. She discovered ] at the age of thirteen, and fell deeply in love with his novels. Later, she cited him as her favorite novelist and the greatest novelist of world literature.<ref> Rand wrote the ideal educational curriculum would be "] in philosophy, ] in economics, ] in education, ] in literature." Long, Roderick: {{cite web|url=http://www.mises.org/fullstory.aspx?Id=1738|title="Ayn Rand's Contribution to the Cause of Freedom"|date=]}}</ref> | |||

| === Early fiction === | |||

| ] occupies a group of early 18th-century buildings on the ] embankment of ].]]Rand was twelve at the time of the ], and her family life was disrupted by the rise of the ] party. Her father's pharmacy was confiscated by the Soviets, and the family fled to ] to recover financially. When Crimea fell to the Bolsheviks in 1921, Rand burned her diary, which contained vitriolic anti-Soviet writings.<ref name="Chronology"/> Rand then returned to St. Petersburg ("Petrograd") to attend university.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iep.utm.edu/r/rand.htm|title="Ayn Rand"|date=]}} at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy</ref> She studied philosophy and history at the ]. Her major literary discoveries were the works of ], ] and ]. She admired Rostand for his richly romantic imagination and Schiller for his grand, heroic scale. She admired Dostoevsky for his sense of drama and his intense moral judgments, but was deeply against his philosophy and his sense of life.<ref> Roger Donway, {{cite web|url=http://www.objectivistcenter.org/ct-104-Dostoevsky_Nietzsche_Ayn_Rands_Moral_Triad.aspx|title="Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, and Ayn Rand's Moral Triad."|accessdate=2006-03-23}} Donway writes that Rand's objectivism "brought full circle the three-way argument that Chernyshevsky and Pisarev; the Underground Man and Nietzsche; and Dostoevsky the Christian philosopher conducted in Russia after 1860."</ref> She completed a three-year program in the department of Social Pedagogy that included history, philology and law, and received Certificate of Graduation (Diploma No. 1552) on ] ].<ref>Sciabarra, Chris Matthew. {{cite web|title="The Rand Transcript."|url=http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sciabarra/essays/randt2.htm| | |||

| {{see also|Night of January 16th|We the Living|Anthem (novella)}} | |||

| accessdate=2006-03-23}}</ref> She also encountered the philosophical ideas of ], and loved his exaltation of the heroic and independent individual who embraced egoism and rejected altruism in ''],'' but later rejected his philosophical center of "might is right" when she discovered more of his writings. | |||

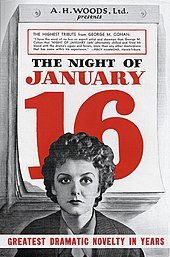

| ]'' opened on Broadway in 1935.]] | |||

| Rand's first literary success was the sale of her screenplay '']'' to ] in 1932, although it was never produced.{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=40, 42}}{{efn|It was later published in '']'' along with other screenplays, plays, and short stories that were not produced or published during her lifetime.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=22}}}} Her courtroom drama '']'', first staged in Hollywood in 1934, reopened successfully on ] in 1935. Each night, a jury was selected from members of the audience; based on its vote, one of two different endings would be performed.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=76, 92}}{{efn|In 1941, ] produced a ]. Rand did not participate in the production and was highly critical of the result.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=78}}{{sfn|Gladstein|2010|p=87}}}} Rand and O'Connor moved to New York City in December 1934 so she could handle revisions for the Broadway production.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=82}} | |||

| Her first novel, the semi-autobiographical{{sfn|Rand|1995|p=xviii}} '']'', was published in 1936. Set in ], it focuses on the struggle between the individual and the state. Initial sales were slow, and the American publisher let it go out of print,{{sfn|Gladstein|2010|p=13}} although European editions continued to sell.<ref>Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing ''We the Living''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2004|p=141}}.</ref> She adapted the story as ], but the Broadway production closed in less than a week.<ref>Britting, Jeff. "Adapting ''We the Living''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2004|p=164}}.</ref>{{efn|In 1942, the novel was adapted without permission into a pair of Italian films, ''Noi vivi'' and ''Addio, Kira''. After Rand's post-war legal claims over the piracy were settled, the films were re-edited with her approval and released as '']'' in 1986.<ref>Britting, Jeff. "Adapting ''We the Living''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2004|pp=167–176}}.</ref>}} After the success of her later novels, Rand released a revised version in 1959 that has sold over three million copies.<ref>Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing ''We the Living''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2004|p=143}}.</ref> | |||

| Rand continued to write short stories and screenplays. She entered the State Institute for Cinema Arts in 1924 to study screenwriting; in late 1925, however, she was granted a ] to visit American relatives. | |||

| Rand started her next major novel, '']'', in December 1935,{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=98}} but took a break from it in 1937 to write her novella '']''.{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=54–55}} The novella presents a ] future world in which ] collectivism has triumphed to such an extent that the word ''I'' has been forgotten and replaced with ''we''.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=50}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=102}} Protagonists Equality 7-2521 and ] eventually escape the collectivistic society and rediscover the word ''I''.{{Sfn|Gladstein|2010|pp=24–25}} It was published in England in 1938, but Rand could not find an American publisher at that time. As with ''We the Living'', Rand's later success allowed her to get a revised version published in 1946, and this sold over 3.5{{nbs}}million copies.<ref>Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing ''Anthem''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2005a|pp=24–27}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Immigration and marriage=== | |||

| In February 1926, she arrived in the ] at the age of 21, entering by ship through ], which would ultimately become her home. She was profoundly moved by the ], later describing it in one of her novels, ''The Fountainhead'': "I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York's skyline, the sky over New York and the will of man made visible. What other religion do we need? I feel that if a war came to threaten this, I would throw myself into space, over the city, and protect these buildings with my body."<ref>Miller, Eric {{cite web|url=http://www.newcolonist.com/aynrand.html|title="City of Life: Ayn Rand's New York."|date=]}}</ref> | |||

| === ''The Fountainhead'' and political activism === | |||

| After a brief stay with her relatives in ], she resolved never to return to the ], and set out for ] to become a ]. Already using ''Rand'' as a ] ]<ref name="name-ari"/> of her surname, she then adopted the name ''Ayn'', an adaptation of a "Finnish feminine name", most likely "Aino" or "Aina".<ref name="name-ari"> | |||

| {{see also|The Fountainhead|The Fountainhead (film)}} | |||

| ARI Biographical researcher Drs. Gotthelf and Berliner note that while still in Russia, Anna used the name "Rand", which is a cyrillic contraction of Rosenbaum. They also note the Finnish origin of Ayn. | |||

| During the 1940s, Rand became politically active. She and her husband were full-time volunteers for Republican ]'s 1940 presidential campaign.{{sfn|Britting|2004|p=57}} This work put her in contact with other intellectuals sympathetic to free-market capitalism. She became friends with journalist ], who introduced her to the ] economist ]. Despite philosophical differences with them, Rand strongly endorsed the writings of both men, and they expressed admiration for her. Mises once called her "the most courageous man in America", a compliment that particularly pleased her because he said "man" instead of "woman".{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=114}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=249}} Rand became friends with libertarian writer ]. Rand questioned her about American history and politics during their many meetings, and gave Paterson ideas for her only non-fiction book, '']''.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=75–78}}{{efn|Their friendship ended in 1948 after Paterson made what Rand considered rude comments to valued political allies.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=130–131}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=214–215}}}} | |||

| {{cite web|url=http://www.aynrand.org/site/PageServer?pagename=about_ayn_rand_faq_index2#ar_q3b|title="What is the origin of "Rand"?"|accessdate=2006-03-28}} | |||

| </ref> She might have been referring to the Finnish author ]. Her surname may also have come from the Estonian word ''rand'', meaning ''coast'' or ''shore''.<ref name=estonian>{{cite web | url=http://dict.ibs.ee/translate.cgi?word=rand&language=Estonian |title = Estonian Dictionary | accessdate = 2007-03-16 }}</ref><!-- | |||

| This was in the talk-archive (#2), citing this article's early history (Aug 12 2005): | |||

| A possibly more correct theory for her last name is that it has the same source as her first name, | |||

| from a favorite Finnish-Estonian, female, liberated author Aino Kallas and her typewriter (Sperry-Rand). Ayn is the Anglicized version of the Finnish, | |||

| additionally mythologic, Kalevala name Aino (the one and only) and Ayn is thus pronounced Ein (eye + n). | |||

| Then this (archive 6 I think): | |||

| She changed her name to protect her family still living in the Soviet Union from reprisals; she also saw it as a way to break with her past | |||

| and start a new life in the US. She did not consider this an act of bowing to "societal pressure," as she stated that "morality ends where a gun begins" | |||

| and that "one doesn't stop the juggernaut by throwing oneself in front of it." I don't know why Branden changed his name from Blumenthal; | |||

| if there's a citation that he did it in deference to "societal pressure," than it belongs. Until then, I'm deleting it. LaszloWalrus 01:43, 25 March 2006 (UTC) | |||

| --> | |||

| ]'' was Rand's first bestseller.]] | |||

| Initially, Rand struggled in ] and took odd jobs to pay her basic living expenses. A chance face-to-face meeting with famed director ] led to a job as an ] in his film ''],'' and subsequent work as a script reader.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aynrand.org/site/PageServer?pagename=about_ayn_rand_aynrand_biography|title="Ayn Rand Biography"|accessdate=2006-03-23}} at AynRand.org </ref> She also worked as the head of the costume department at ] Studios.<ref name="Leiendecker"> Leiendecker, Harold. {{cite web|url=http://www.eckerd.edu/aspec/writers/atlas_shrugged.htm|title="Atlas Shrugged."|accessdate=2006-03-30}}</ref> While working on the film, she intentionally bumped into an aspiring young actor, ], who caught her eye. The two married on ], ], and remained married for fifty years, until O'Connor's death in 1979 at the age of 82. In 1931, Rand became a ] of the United States; she was fiercely proud of the United States, and in later years said to the graduating class at ], "I can say - not as a patriotic bromide, but with full knowledge of the necessary metaphysical, epistemological, ethical, political and aesthetic roots - that the United States of America is the greatest, the noblest and, in its original founding principles, the only moral country in the history of the world."<ref> Rand, Ayn. {{cite web|title="Philosophy: Who Needs It?"|url=http://gos.sbc.edu/r/rand.html|accessdate=2006-03-31}} Address to the Graduating Class Of The United States Military Academy at West Point, New York - March 6, 1974. </ref> | |||

| Rand's first major success as a writer came in 1943 with ''The Fountainhead'',{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=61–78}} a novel about an uncompromising architect named Howard Roark and his struggle against what Rand described as "second-handers" who attempt to live through others, placing others above themselves. Twelve publishers rejected it before ] accepted it at the insistence of editor Archibald Ogden, who threatened to quit if his employer did not publish it.{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=58–61}} While completing the novel, Rand was prescribed ], an ], to fight fatigue.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=85}} The drug helped her to work long hours to meet her deadline for delivering the novel, but afterwards she was so exhausted that her doctor ordered two weeks' rest.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=89}} Her use of the drug for approximately three decades may have contributed to mood swings and outbursts described by some of her later associates.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=178}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=304–305}} | |||

| The success of ''The Fountainhead'' brought Rand fame and financial security.{{sfn|Doherty|2007|p=149}} In 1943, she sold the film rights to ] and returned to Hollywood to write the screenplay. Producer ] then hired her as a screenwriter and script-doctor for screenplays including '']'' and '']''.{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=68–71}} Rand became involved with the ] ] and ].{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=100–101, 123}} In 1947, during the ], she testified as a "friendly witness" before the United States ] that the 1944 film '']'' grossly misrepresented conditions in the ], portraying life there as much better and happier than it was.{{sfn|Mayhew|2005b|pp=91–93, 188–189}} She also wanted to criticize the lauded 1946 film '']'' for what she interpreted as its negative presentation of the business world but was not allowed to do so.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=125}} When asked after the hearings about her feelings on the investigations' effectiveness, Rand described the process as "futile".{{sfn|Mayhew|2005b|p=83}} | |||

| ==Fiction== | |||

| Rand viewed herself equally as a novelist and a philosopher, as she said "(I am) both, and for the same reason." It has been suggested that Rand's practice of presenting her philosophy in fiction and non-fiction books aimed at a general audience, rather than publications in ]ed journals, have encouraged a negative view.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Rand's defenders note that she is part of a long tradition of authors who wrote philosophically rich fiction - including ], ], ] and ], and that philosophers such as ] presented their philosophies in both fictional and non-fictional forms. | |||

| After several delays, the ] of ''The Fountainhead'' was released in 1949. Although it used Rand's screenplay with minimal alterations, she "disliked the movie from beginning to end" and complained about its editing, the acting and other elements.{{sfn|Britting|2004|p=71}} | |||

| In an article about Rand, that appeared in ] in 1991, it is stated that "Rand’s novels sell some 300,000 copies a year, exhorting readers to think big about themselves, build big and earn big. New editions of all her books carry postcards for readers who might be inclined to learn more about Objectivism, the author’s credo, a blending of free markets, reason and individualism."<ref>''Still Spouting," The Economist, November 25, 1999</ref> | |||

| === ''Atlas Shrugged'' and Objectivism === | |||

| ===Early works=== | |||

| {{see also|Atlas Shrugged|Objectivism|Objectivist movement}} | |||

| Her first literary success came with the sale of her screenplay ''Red Pawn'' in 1932 to ]: "] later considered it for ], but Russian scenarios were out of favour and it was ditched."<ref name="Turner">Turner, Jenny. {{cite web|title="As Astonishing as Elvis"|url=http://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n23/turn03_.html|date=]}} Review of Jeff Briting's biography, ''Ayn Rand''.</ref> Rand then wrote the play '']'' in 1934, which was produced on ]. The play was a ] in which a jury chosen from the audience decided the verdict, leading to one of two possible endings.<ref> "A Sense of Life" homepage. </ref> | |||

| ]''.<ref>Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing ''Anthem''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2005a|p=26}}.</ref>]] | |||

| Following the publication of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand received many letters from readers, some of whom the book had influenced profoundly.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=91}} In 1951, Rand moved from Los Angeles to New York City, where she gathered a group of these admirers who met at Rand's apartment on weekends to discuss philosophy. The group included future ] ], a young psychology student named Nathan Blumenthal (later ]) and his wife ], and Barbara's cousin ]. Later, Rand began allowing them to read the manuscript drafts of her new novel, ''Atlas Shrugged''.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=240–243}} In 1954, her close relationship with Nathaniel Branden turned into a romantic affair. They informed both their spouses, who briefly objected, until Rand "spn out a deductive chain from which you just couldn't escape", in Barbara Branden's words, resulting in her and O'Connor's assent.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=256–259}} Historian ] concludes that O'Connor was likely "the hardest hit" emotionally by the affair.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=157}} | |||

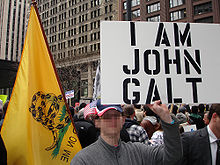

| Published in 1957, ''Atlas Shrugged'' is considered Rand's '']''.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=106}}{{sfn|Mayhew|2005b|p=78}} She described the novel's theme as "the role of the mind in man's existence—and, as a corollary, the demonstration of a new moral philosophy: the morality of rational self-interest".<ref>Salmieri, Gregory. "''Atlas Shrugged'' on the Role of the Mind in Man's Existence". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2009|p=248}}.</ref> It advocates the core tenets of Rand's philosophy of ] and expresses her concept of human achievement. The plot involves a ]n United States in which the most creative industrialists, scientists, and artists respond to a ] government by going on ] and retreating to a hidden valley where they build an independent free economy. The novel's hero and leader of the strike, ], describes it as stopping "the motor of the world" by withdrawing the minds of individuals contributing most to the nation's wealth and achievements.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=54}} The novel contains an exposition of Objectivism in a lengthy monologue delivered by Galt.<ref>] "The Role and Essence of John Galt's Speech in Ayn Rand's ''Atlas Shrugged''". In {{harvnb|Younkins|2007|p=99}}.</ref> | |||

| Rand then published two novels, '']'' (1936), and '']'' (1938): "Rand described ''We the Living'' as the most autobiographical of her novels, its theme being the brutality of life under communist rule in Russia."<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.iep.utm.edu/r/rand.htm|title="Ayn Rand"|date=2006-03023}} at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.</ref> Its harsh anti-communist tone met with mixed reviews in the U.S., where the period of ] was sometimes known as "]" in reference to the high-water mark of sympathy for socialist ideals. Stephen Cox, at ], observed that ''We the Living'' "was published at the height of Russian socialism's popularity among leaders of American opinion. It failed to attract an audience."<ref name="Cox">Cox, Stephen. {{cite web|title="Anthem: An appreciation."|url=http://www.theatlassociety.org/cox_anthem_appreciation.asp|accessdate=2006-03-24}}</ref> | |||

| Despite many negative reviews, ''Atlas Shrugged'' became an international bestseller,{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=2}} but the reaction of intellectuals to the novel discouraged and depressed Rand.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=178}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=303–306}} ''Atlas Shrugged'' was her last completed work of fiction, marking the end of her career as a novelist and the beginning of her role as a popular philosopher.{{sfn|Younkins|2007|p=1}} | |||

| Frank O'Connor and Ayn Rand spent the summer of 1937 in ], while Frank worked in ],<ref name="Cox"/> and Ayn planned ''Anthem,'' a ] vision of a futuristic society where collectivism has triumphed. ''Anthem'' did not find a publisher in the United States and was first published in England. | |||

| In 1958, Nathaniel Branden established the Nathaniel Branden Lectures, later incorporated as the ] (NBI), to promote Rand's philosophy through public lectures. He and Rand co-founded '']'' (later renamed ''The Objectivist'') in 1962 to circulate articles about her ideas;{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=321}} she later republished some of these articles in book form. Rand was unimpressed by many of the NBI students{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=303}} and held them to strict standards, sometimes reacting coldly or angrily to those who disagreed with her.{{sfn|Doherty|2007|pp=237–238}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=329}}{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=235}} Critics, including some former NBI students and Branden himself, later said the NBI culture was one of intellectual conformity and excessive reverence for Rand. Some described the NBI or the ] as a ] or religion.{{sfn|Gladstein|2010|pp=105–106}}{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=232–233}} Rand expressed opinions on a wide range of topics, from literature and music to sexuality and facial hair. Some of her followers mimicked her preferences, wearing clothes to match characters from her novels and buying furniture like hers.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=236–237}} Some former NBI students believed the extent of these behaviors was exaggerated, and the problem was concentrated among Rand's closest followers in New York.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=235}}{{sfn|Doherty|2007|p=235}} | |||

| ===The Fountainhead=== | |||

| {{Main|The Fountainhead}} | |||

| === Later years === | |||

| Rand's first major professional success came with her best-selling novel '']'' (1943), which she wrote over a period of seven years. The novel was rejected by twelve publishers, who thought it was too intellectual and opposed to the mainstream of American thought. It was finally accepted by the ] publishing house, thanks mainly to a member of the editorial board, Archibald Ogden, who praised the book in the highest terms ("If this is not the book for you, then I am not the editor for you.") and finally prevailed.<ref name="Cato"> ], {{cite web|url=http://www.cato.org/special/threewomen/fountainhead.html|title="''The Fountainhead''"|accessdate=2006-03-30}}</ref> Eventually, ''The Fountainhead'' was a worldwide success, bringing Rand fame and financial security. In 1949 it was made into a ]. In the sixty years since it was published, Rand's novel has sold six million copies, and continues to sell about 100,000 copies per year.<ref name="Cato"/> | |||

| Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Rand developed and promoted her Objectivist philosophy through nonfiction and speeches,{{sfn|Branden|1986|pp=315–316}}{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=14}} including annual lectures at the ].{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=16}} In answers to audience questions, she took controversial stances on political and social issues. These included supporting abortion rights,{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=320–321}} opposing the ] and the ] (but condemning many ] as "bums"),{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=228–229, 265}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=352}} supporting Israel in the ] of 1973 against a coalition of Arab nations as "civilized men fighting savages",{{sfn|Brühwiler|2021|p=202 n114}}{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=266}} claiming ] had the right to invade and take land inhabited by ],{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=266}}<ref>Thompson, Stephen. "Topographies of Liberal Thought: Rand and Arendt and Race". In {{harvnb|Cocks|2020|p=237}}.</ref> and calling homosexuality "immoral" and "disgusting", despite advocating the repeal of all laws concerning it.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=362, 519}} She endorsed several ] candidates for president of the United States, most strongly ] in ].{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=204–206}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=322–323}} | |||

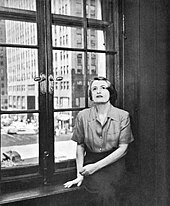

| ] in ]{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=405}}]] | |||

| Following the success of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand wrote screenplays for two movies, '']'' and ''You Came Along''. | |||

| In 1964, Nathaniel Branden began an affair with the young actress ], whom he later married. Nathaniel and Barbara Branden kept the affair hidden from Rand. As her relationship with Nathaniel Branden deteriorated, Rand had her husband be present for difficult conversations between her and Branden.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=360–361}} In 1968, Rand learned about Branden's relationship with Scott. Though her romantic involvement with Nathaniel Branden was already over,{{sfn|Britting|2004|p=101}} Rand ended her relationship with both Brandens, and the NBI closed.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=374–375}} She published an article in ''The Objectivist'' repudiating Nathaniel Branden for dishonesty and "irrational behavior in his private life".{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=378–379}} In subsequent years, Rand and several more of her closest associates parted company.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=276}}{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=398–400}} | |||

| Rand's younger sister Eleonora Drobisheva (née ''Rosenbaum'', 1910–1999) visited her in the US in 1973 at the former's invitation, but did not accept her lifestyle and views, as well as finding little literary merit in her works. She subsequently returned to the Soviet Union and spent the rest of her life in Leningrad (later ]).<ref>https://biography.wikireading.ru/hj9OluXAZo</ref> | |||

| ===Atlas Shrugged=== | |||

| {{Main|Atlas Shrugged}} | |||

| ]," the largest sculptural work at ] in ], by Lee Lawrie and Rene Chambellan, in the ] style. (1936)]]Rand's ], ''],'' was published in 1957. Due to the success of ''The Fountainhead,'' the initial printing was 100,000 copies,<ref>]. {{cite web|title="Big Sister is Watching You."|url=http://www.nationalreview.com/flashback/flashback200501050715.asp|accessdate=2006-03-24}} Reprint of contemporary review of ''Atlas Shrugged'' from ''].''</ref> and the book went on to become an international bestseller. (The frequent claim<ref>{{cite web|title=Atlas Shrugged review at Amazon.com|url=http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0452011876/ref=dp_proddesc_2/002-9125768-7844058?%5Fencoding=UTF8&n=283155&v=glance|accessdate=2006-03-24}}</ref> that ''Atlas Shrugged'' was later found to be the "second most influential book in America, after ],"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.google.com/search?hl=en&lr=&q=%22Atlas+Shrugged%22+most+popular+Library+of+Congress&btnG=Search|title=Google.com search|accessdate=2006-03-24}} showing this widespread claim.</ref> may be an exaggeration of the findings of one 1991 survey; however, it has been cited in numerous interviews as the book that most influenced the subject.)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.noblesoul.com/orc/books/rand/atlas/faq.html#Q6.4|title=Rand FAQ at Noble Soul|accessdate=2006-03-25}} Provides detail about the actual survey and findings.</ref><ref>Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. {{cite web|url=http://www.violetbooks.com/aynrand.html|title="'Ayn Rand, More Popular than God!' Objectivists Allege!"|accessdate=2006-03-24}} Although the author appears to have a strong dislike of Rand and her supporters, her conclusions about the "Book of the Month Club" survey appear to be supported.</ref> | |||

| Rand had surgery for lung cancer in 1974 after decades of heavy smoking.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=391–393}} In 1976, she retired from her newsletter and, despite her lifelong objections to any government-run program, was enrolled in and subsequently claimed ] and ] with the aid of a social worker.{{sfn|McConnell|2010|pp=520–521}}{{sfn|Weiss|2012|p=62}} Her activities in the Objectivist movement declined, especially after her husband died on November{{nbs}}9, 1979.{{sfn|Branden|1986|pp=392–395}} One of her final projects was a never-completed television adaptation of ''Atlas Shrugged''.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=406}} | |||

| ''Atlas Shrugged'' is often seen as Rand's most extensive statement of Objectivism in any of her works of fiction. In its appendix, she offered this summary: | |||

| :"My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute." | |||

| On March{{nbs}}6, 1982, Rand died of heart failure at her home in New York City.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=410}} Her funeral included a {{convert|6|ft|m|adj=on}} floral arrangement in the shape of a dollar sign.{{sfn|Gladstein|2010|p=20}} In her will, Rand named Peikoff as her heir.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=400}} | |||

| The theme of ''Atlas Shrugged'' is "The role of man's mind in society." Rand upheld the industrialist as one of the most admirable members of any society and fiercely opposed the popular resentment accorded to industrialists. This led her to envision a novel wherein the industrialists of America go on strike and retreat to a mountainous hideaway. The American economy and its society in general slowly start to collapse. The government responds by increasing the already stifling controls on industrial concerns. The novel, which includes elements of mystery and science fiction, deals with issues as wide-ranging as sex, music, medicine, politics and human ability. | |||

| == Literary approach, influences and reception == | |||

| ==Philosophy and the Objectivist movement== | |||

| Rand described her approach to literature as "]".{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=179}} She wanted her fiction to present the world "as it could be and should be", rather than as it was.<ref>Britting, Jeff. "Adapting ''The Fountainhead'' to Film". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2006|p=96}}.</ref> This approach led her to create highly stylized situations and characters. Her fiction typically has ] who are heroic individualists, depicted as fit and attractive.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=26}} Her villains support duty and collectivist moral ideals. Rand often describes them as unattractive, and some have names that suggest negative traits, such as Wesley Mouch in ''Atlas Shrugged''.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=27}}{{sfn|Baker|1987|pp=99–105}} | |||

| {{Main|Objectivism (Ayn Rand)}} | |||

| Rand considered plot a critical element of literature,{{sfn|Torres|Kamhi|2000|p=64}} and her stories typically have what biographer Anne Heller described as "tight, elaborate, fast-paced plotting".{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=64}} ]s are a common plot element in Rand's fiction; in most of her novels and plays, the main female character is romantically involved with at least two men.{{sfn|Duggan|2019|p=44}}<ref>Wilt, Judith. "The Romances of Ayn Rand". In {{harvnb|Gladstein|Sciabarra|1999|pp=183–184}}.</ref> | |||

| Rand's Objectivist philosophy encompasses positions on ], ], ], ] and ]. Along with ], his wife ], and others including ] and ] (jokingly designated "]"), Rand launched the ] movement to promote her philosophy. | |||

| === |

=== Influences === | ||

| ].]] | |||

| She was greatly influenced by ]. Some have observed parallels with ], and she was vociferously opposed to some of the views of ]. Rand also claimed to share intellectual lineage with ], who conceptualized the ideas that individuals "own themselves," have a right to the products of their own labor, and have ] to life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness and property,<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.mondopolitico.com/ideologies/atlantis/whatisobjectivism.htm|title="What is objectivism?"|accessdate=2006-04-10}}. Refers to a Leonard Peikoff lecture describing the connection between Rand and ]'s ] (1689).</ref> and more generally with the philosophies of the ] and the ]. She occasionally remarked with approval on specific philosophical positions of, for example, ] and ]. She seems also to have respected the 20th-century American rationalist ], who, like Rand, believed that "there has been no period in the past two thousand years when have undergone a bombardment so varied, so competent, so massive and sustained as in the last half-century."<ref> Branden, Nathaniel. {{cite web|url=http://www.nathanielbranden.com/catalog/articles_essays/review_of_reason.html|title="Review of ''Reason and Analysis''"|accessdate=2006-04-10}} A review of Blanshard's book, originally published in ''The Objectivist Newsletter'', February 1963.</ref> | |||

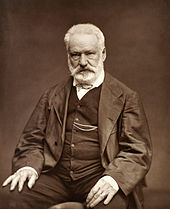

| In school, Rand read works by ], ], ], and ], who became her favorites.{{sfn|Britting|2004|pp=17, 22}} She considered them to be among the "top rank" of ] writers because of their focus on moral themes and their skill at constructing plots.{{sfn|Torres|Kamhi|2000|p=59}} Hugo was an important influence on her writing, especially her approach to plotting. In the introduction she wrote for an English-language edition of his novel '']'', Rand called him "the greatest novelist in world literature".{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=32–33}} | |||

| Although Rand disliked most Russian literature, her depictions of her heroes show the influence of the ]{{sfn|Grigorovskaya|2018|pp=315–325}} and other nineteenth-century Russian writing, most notably the 1863 novel '']'' by ].{{sfn|Kizilov|2021|p=106}}{{sfn|Weiner|2020|pp=6–7}} Scholars of Russian literature see in Chernyshevsky's character Rakhmetov, an "ascetic revolutionist", the template for Rand's literary heroes and heroines.{{sfn|Johnson|2000|pp=47–67}} | |||

| ====Aristotle==== | |||

| Rand's greatest influence was ], especially '']'' ("Logic"); she considered Aristotle the greatest philosopher.<ref>Long, Roderick T. {{cite web|title="Ayn Rand's contribution to the cause of freedom."|url=http://www.mises.org/fullstory.aspx?Id=1738|date=]}}: "Rand always firmly insisted that Aristotle was the greatest and that Thomas Aquinas was the second greatest—her own atheism notwithstanding."</ref> In particular, her philosophy reflects an Aristotelian ] and ] – both Aristotle and Rand argued that "there exists an objective reality that is independent of mind and that is capable of being known."<ref name="Sternberg"> Sternberg, Elaine. {{cite web|title="Why Ayn Rand Matters: Metaphysics, Morals, and Liberty.|url=http://www.dailyspeculations.com/Ayn%20Rand/Ayn-Rand-posts.html|accessdate=2006-04-02}}</ref> Although Rand was ultimately critical of Aristotle's ethics, others have noted her egoistic ethics "is of the '']'' type, close to Aristotle's own...a system of guidelines required by human beings to live their lives successfully, to flourish, to survive as 'man qua man.' "<ref name="Machan"> Machan, Tibor. {{cite web|url=http://www.freemarketnews.com/Analysis/117/3475/2006-01-18.asp?nid=3475&wid=117|title="Cooper on Rand & Aristotle."|accessdate=2006-04-02}}</ref> Younkins argued "that her philosophy diverges from Aristotle’s by considering ] as epistemological and contextual instead of as metaphysical. She envisions Aristotle as a philosophical intuitivist who declared the existence of essences within concretes."<ref name="Younkins"> Younkins, Edward W. {{cite web|title="Aristotle: Ayn Rand's Acknowledged Teacher"|url=http://rebirthofreason.com/Articles/Younkins/Aristotle_Ayn_Rands_Acknowledged_Teacher.shtml|accessdate=2006-04-03}}</ref> | |||

| Rand's experience of the Russian Revolution and early Communist Russia influenced the portrayal of her villains. Beyond ''We the Living'', which is set in Russia, this influence can be seen in the ideas and rhetoric of Ellsworth Toohey in ''The Fountainhead'',{{sfn|Rosenthal|2004|pp=220–223}} and in the destruction of the economy in ''Atlas Shrugged''.{{sfn|Kizilov|2021|p=109}}{{sfn|Rosenthal|2004|pp=200–206}} | |||

| ====Nietzsche==== | |||

| In her early life, Rand admired the work of ], and did share "Nietzsche's reverence for human potential and his loathing of Christianity and the philosophy of Immanuel Kant,"<ref name="Hicks"> Hicks, Stephen. {{cite web|url=http://www.objectivistcenter.org/ct-184-Big_Game_Small_Gun.aspx|title="Big Game, Small Gun?"|accessdate=2006-03-30}} A review of Ronald E. Merrill's ''The Ideas of Ayn Rand''.</ref> but eventually became critical, seeing his philosophy as emphasizing emotion over reason and subjective interpretation of reality over actual reality.<ref name="Hicks"/> There is debate about the extent of the relationship between Rand's views and Nietzsche's, and over what seemed to be an evolution of Rand's view of Nietzsche. Allan Gotthelf, in ''On Ayn Rand'', describes the first edition of ''We the Living'' as very sympathetic to Nietzschean ideas. Bjorn Faulkner and Karen Andre, characters from ''The Night of January 16th'', exemplify certain aspects of Nietzsche's views. Ronald Merrill, author of ''The Ideas of Ayn Rand'' identified a passage in ''We the Living'' that Rand had omitted from the 1959 reprint: "In it, the heroine entertains (though finally rejects) sentiments explicitly attributed to Nietzsche about the justice of sacrificing the weak for the strong."<ref name="McLemee"> McLemee, Scott. {{cite web|title="The Heirs of Ayn Rand."|url=http://www.mclemee.com/id39.html|accessdate=2006-04-03}} originally in ''Lingua Franca'' , September 1999. </ref> Rand herself denied a close intellectual relationship with Nietzsche and characterized changes in later editions of ''We the Living'' as stylistic and grammatical. | |||

| Rand's descriptive style echoes her early career writing scenarios and scripts for movies; her novels have many narrative descriptions that resemble early Hollywood movie scenarios. They often follow common film editing conventions, such as having a broad ] description of a scene followed by ] details, and her descriptions of women characters often take a "]" perspective.<ref>Gladstein, Mimi Reisel. "Ayn Rand's Cinematic Eye". In {{harvnb|Younkins|2007|pp=109–111}}.</ref> | |||

| The destruction of Gail Wynand in '']'' is an example of her later view, a rejection of Nietzsche, that the great cannot succeed by sacrificing the masses: "her journals suggest a rejection of traditional false-alternative ethics. Her May 15 entry, for example, identifies the error of Nietzscheans such as Gail Wynand: in trying to achieve power, they use the masses, but at the cost of their ideals and standards, and thus become "a slave to those masses." The independent man, therefore, will not make his success dependent upon the masses."<ref name="Hicks"/> Although Rand disagreed with many of Nietzsche's ideas, the introduction to the 25th anniversary edition of '']'' concludes with Nietzsche's statement, "The noble soul has reverence for itself." | |||

| === |

=== Contemporary reviews === | ||

| ] | |||

| {{see also|Critique of Pure Reason}} | |||

| The first reviews Rand received were for ''Night of January 16th''. Reviews of the Broadway production were largely positive, but Rand considered even positive reviews to be embarrassing because of significant changes made to her script by the producer.{{sfn|Branden|1986|pp=122–124}} Although Rand believed that ''We the Living'' was not widely reviewed, over 200 publications published approximately 125 different reviews. Overall, they were more positive than those she received for her later work.<ref>Berliner, Michael S. "Reviews of ''We the Living''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2004|pp=147–151}}.</ref> ''Anthem'' received little review attention, both for its first publication in England and for subsequent re-issues.<ref>Berliner, Michael S. "Reviews of ''Anthem''". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2005a|pp=55–60}}.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Rand was deeply opposed to the philosophy of ]. Their divergence is greatest in ] and ], particularly with regard to Kant's analytic-synthetic dichotomy, rather than the ] of Kant's well known ] (her critique of Kant's ethics is directly rooted in Kant's metaphysics and epistemology). Rand and Kant had significantly different theories of concepts, identity and consciousness: In ], reason is the highest virtue, and reason and logic can be used to understand objective reality. Kant believed that we cannot have certain knowledge about the true nature of reality ("things-in themselves"), but only of the manner in which we perceive reality. For example, we can know for certain that we are unable to conceive of an object which is not extended - i.e., occupies physical space - but it does not follow that no object that is not extended can exist. Rand believed that if an object has an effect upon the senses, then that effect upon the senses gives us knowledge about the object itself. At the most basic level, it informs us that that object is of a particular character such that when it interacts with one's sense organs it causes a particular sensation, and that is knowledge about a quality of the object itself. In Rand's view, Kant's dichotomy severed rationality and reason from the real world. In Rand's words, <blockquote>"I have mentioned in many articles that Kant is the chief destroyer of the modern world... You will find that on every fundamental issue, Kant's philosophy is the exact opposite of Objectivism."<ref name="Hsieh"> Hsieh, Diana. {{cite web|title="David Kelley versus Ayn Rand on Kant."|url=http://www.dianahsieh.com/blog/2006/02/david-kelley-versus-ayn-rand-on-kant.html|accessdate=2006-03-30}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| In the final issue of ''The Objectivist,'' she further wrote, <blockquote>"Suppose you met a twisted, tormented young man and... discovered that he was brought up by a man-hating monster who worked systematically to paralyze his mind, destroy his self-confidence, obliterate his capacity for enjoyment and undercut his every attempt to escape... Western civilization is in that young man's position. The monster is Immanuel Kant."<ref name="Hsieh"> Hsieh, Diana. {{cite web|title="David Kelley versus Ayn Rand on Kant."|url=http://www.dianahsieh.com/blog/2006/02/david-kelley-versus-ayn-rand-on-kant.html|accessdate=2006-03-30}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Rand's first bestseller, ''The Fountainhead'', received far fewer reviews than ''We the Living'', and reviewers' opinions were mixed.<ref name="tfreviews">Berliner, Michael S. "''The Fountainhead'' Reviews". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2006|pp=77–82}}.</ref> ]'s positive review in '']'', which called the author "a writer of great power" who wrote "brilliantly, beautifully and bitterly",{{sfn|Pruette|1943|p=BR7}} was one that Rand greatly appreciated.{{sfn|Heller|2009|p=152}} There were other positive reviews, but Rand dismissed most of them for either misunderstanding her message or for being in unimportant publications.<ref name="tfreviews"/> Some negative reviews said the novel was too long;{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|pp=117–119}} others called the characters unsympathetic and Rand's style "offensively pedestrian".<ref name="tfreviews"/> | |||

| A more complicated difference between Ayn Rand's metaphysics and that of Immanuel Kant is the reality of space, time and number. For Kant, these are merely built into the human mode of perception and are not present in any thing-in-itself. One might hope that the following analogy applies: Color is not present in an object, but is purely a construct of our minds. Yet this is not enough for Kant, because color corresponds to some objective quality (quality of the object) while space, time and number have no such relationship to objectivity. (See ''Critique of Pure Reason'' B38-B45.) Rand would most certainly have disagreed with this concept, taking the fact that our faculty of perception has a particular (limited) identity not to be a charge against it, but a demonstration of its objectivity. This is a subtle though not insignificant point of difference that cannot be uncontroversially explicated in a few words. | |||

| ''Atlas Shrugged'' was widely reviewed, and many of the reviews were strongly negative.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|pp=117–119}}<ref name="asreviews">Berliner, Michael S. "The ''Atlas Shrugged'' Reviews". In {{harvnb|Mayhew|2009|pp=133–137}}.</ref> ''Atlas Shrugged'' received positive reviews from a few publications,<ref name="asreviews"/> but Rand scholar ] later wrote that {{qi|reviewers seemed to vie with each other in a contest to devise the cleverest put-downs}}, with reviews including comments that it was {{qi|written out of hate}} and showed {{qi|remorseless hectoring and prolixity}}.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|pp=117–119}} ] wrote what was later called the novel's most "notorious" review{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=174}}{{sfn|Doherty|2007|p=659 n4}} for the conservative magazine '']''. He accused Rand of supporting a godless system (which he related to that of the ]), claiming, {{qi|From almost any page of ''Atlas Shrugged'', a voice can be heard ... commanding: 'To a gas chamber—go!'}}.{{sfn|Chambers|1957|p=596}}{{efn|Although she was previously friendly with ''National Review'' editor ], Rand cut off all contact with him after the review was published.{{sfn|Heller|2009|pp=285–286}} Historian Jennifer Burns describes the review as a break between Buckley's religious conservatism and non-religious libertarianism.{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=175}}}} | |||

| ===Founds "The Collective"=== | |||

| {{main|The Ayn Rand Collective|Objectivist movement}} | |||

| In 1950 Rand moved to 120 East 34th Street<ref> Branden, Nathaniel. {{cite web|title="Devers Branden and Ayn Rand."|url=http://rous.redbarn.org/objectivism/writing/NathanielBranden/DeversAndAyn.html|accessdate=2006-04-06}}</ref> in ], and formed a group with the deliberately ironic name "]," which included future Federal Reserve chairman ] and a young psychology student named Nathan Blumenthal (later ]), who had been profoundly influenced by ''The Fountainhead.'' According to Branden, "I wrote Miss Rand a letter in 1949... I was invited to her home for a personal meeting in March, 1950, a month before I turned twenty."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nathanielbranden.com/catalog/rand.php#|title=Nathaniel Branden discusses his relationship with Rand.|date=]}}</ref> | |||

| Rand's nonfiction received far fewer reviews than her novels. The tenor of the criticism for her first nonfiction book, '']'', was similar to that for ''Atlas Shrugged''.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=119}} Philosopher ] likened her certainty to "the way philosophy is written in the Soviet Union",{{sfn|Hook|1961|p=28}} and author ] called her viewpoint "nearly perfect in its immorality".{{sfn|Vidal|1962|p=}} These reviews set the pattern for reaction to her ideas among ] critics.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=193–194}} Her subsequent books got progressively less review attention.{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=119}} | |||

| The group originally started out as informal gathering of friends who met with Rand on weekends at her apartment to discuss philosophy; later the Collective would proceed to play a larger, more formal role, helping edit '']'' and promoting Rand's philosophy through the ] ("the N.B.I.") Many Collective members gave lectures at the NBI and in cities across the United States, while others wrote articles for its sister newsletter, ''].'' | |||

| === Academic assessments of Rand's fiction === | |||

| After several years, Rand and Branden's friendly relationship blossomed into a romantic affair, despite the fact that both were married at the time. Their spouses were persuaded to accept this affair but it eventually led to Branden's separation from and then divorce of his wife. | |||

| Academic consideration of Rand as a literary figure during her life was limited. Mimi Reisel Gladstein could not find any scholarly articles about Rand's novels when she began researching her in 1973, and only three such articles appeared during the rest of the 1970s.{{sfn|Gladstein|2003|pp=373–374, 379–381}} Since her death, scholars of English and American literature have continued largely to ignore her work,{{sfn|Gladstein|2003|p=375}} although attention to her literary work has increased since the 1990s.{{sfn|Gladstein|2003|pp=384–391}} Several academic book series about important authors cover Rand and her works,{{efn|These include Twayne's United States Authors (''Ayn Rand'' by James T. Baker), Twayne's Masterwork Studies (''The Fountainhead: An American Novel'' by Den Uyl and ''Atlas Shrugged: Manifesto of the Mind'' by Gladstein), and Re-reading the Canon (''Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand'', edited by Gladstein and Sciabarra).{{sfn|Sciabarra|2003|p=43}}}} as do popular study guides like ] and ].{{sfn|Gladstein|2003|pp=382–389}} In '']'' entry for Rand written in 2001, ] declared that {{qi|Rand wrote the most intellectually challenging fiction of her generation.}}{{sfn|Lewis|2001}} In 2019, ] described Rand's fiction as popular and influential on many readers, despite being easy to criticize for {{qi|her cartoonish characters and melodramatic plots, her rigid moralizing, her middle- to lowbrow aesthetic preferences{{nbs}}... and philosophical strivings}}.{{sfn|Duggan|2019|p=4}} | |||

| == Philosophy == | |||

| Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Rand developed and promoted her Objectivist philosophy through both her fiction and non-fiction works, and by giving talks at several east-coast universities, largely through the ] which Branden established to promote her philosophy: "''],'' later expanded and renamed simply ''The Objectivist'' contained essays by Rand, Branden, and other associates...that analyzed current political events and applied the principles of Objectivism to everyday life."<ref name="JVL"/> Rand later published some of these in book form. | |||

| {{Objectivist movement}} | |||

| {{Libertarianism US}} | |||

| {{main|Objectivism}} | |||

| Rand called her philosophy "Objectivism", describing its essence as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute".{{sfn|Rand|1992|pp=1170–1171}} She considered Objectivism a ] and laid out positions on ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Gladstein|Sciabarra|1999|p=2}} | |||

| == |

=== Metaphysics and epistemology === | ||

| In metaphysics, Rand supported ] and opposed anything she regarded as mysticism or supernaturalism, including all forms of religion.<ref>Den Uyl, Douglas J. & Rasmussen, Douglas B. "Ayn Rand's Realism". In {{harvnb|Den Uyl|Rasmussen|1986|pp=3–20}}.</ref> Rand believed in ] as a form of ] and rejected ].<ref>Rheins, Jason G. "Objectivist Metaphysics: The Primacy of Existence". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=260}}.</ref> | |||

| Rand held that the only moral social system is '']'' ]. Her political views were strongly ] and hence ] and ]. She exalted what she saw as the heroic ] of rational egoism and individualism. As a champion of rationality, Rand also had a strong opposition to ] and ], which she believed helped foster a crippling culture acting against individual human happiness and success. Rand detested many prominent ] and ] politicians of her time, including prominent anti-Communists, such as ], ], ], and ].<ref> NB that Rand also argued that '']'' was a myth used as an ] accusation to discredit anti-Communists.{{Fact|date=February 2007}}</ref> She opposed US involvement in ], ]<ref name="WWII"> {{cite web|title="Ayn Rand on WWII"|url=http://ariwatch.com/AynRandOnWWII.htm|accessdate=2006-04-07}} Excerpts from Rand's writing, cited at the ARI Watch website.</ref> and the ], although she also strongly denounced ]: "When a nation resorts to war, it has some purpose, rightly or wrongly, something to fight for – and the only justifiable purpose is self-defense."<ref name="honoringvirtue"> {{cite web|url=http://ariwatch.com/HonoringVirtue.htm|title="Honoring Virtue"|accessdate=2006-04-06}} at the ARI website.</ref> | |||

| She opposed U.S. involvement in the ], "If you want to see the ultimate, suicidal extreme of altruism, on an international scale, observe the war in Vietnam – a war in which American soldiers are dying for no purpose whatever,"<ref name="honoringvirtue"/> but also felt that unilateral American withdrawal would be a mistake of ] that would embolden communists and the Soviet Union.<ref name="WWII"/> She said also that she comsidered the anti-Communist ] "futile, because they are not for capitalism but merely against communism." | |||

| Rand also related her aesthetics to metaphysics by defining art as a "selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments".{{sfn|Torres|Kamhi|2000|p=26}} According to her, art allows philosophical concepts to be presented in a concrete form that can be grasped easily, thereby fulfilling a need of human consciousness.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|pp=191–192}} As a writer, the art form Rand focused on most closely was literature. In works such as '']'' and '']'', she described ] as the approach that most accurately reflects the existence of human free will.{{sfn|Gotthelf|2000|p=93}} | |||

| In epistemology, Rand considered all knowledge to be based on forming higher levels of understanding from sense perception, the validity of which she considered ]atic.{{sfn|Gotthelf|2000|p=54}} She described reason as "the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man's senses".<ref>Salmieri, Gregory. "The Objectivist Epistemology". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=283}}.</ref> Rand rejected all claims of non-perceptual knowledge, including {{" '}}instinct,' 'intuition,' 'revelation,' or any form of 'just knowing{{' "}}.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=403 n20}} In her '']'', Rand presented a theory of concept formation and rejected the ].{{sfn|Salmieri|Gotthelf|2005|p=1997}}{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|pp=85–86}} She believed epistemology was a foundational branch of philosophy and considered the advocacy of reason to be the single most significant aspect of her philosophy.<ref>Salmieri, Gregory. "The Objectivist Epistemology". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|pp=271–272}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Economics=== | |||

| Generally, her political thought is in the tradition of ]. She expressed qualified enthusiasm for the economic thought of ] and ]. The ] says that "it was largely as a result of Ayn's efforts that the work of von Mises began to reach its potential audience."<ref>Long, Roderick T. {{cite web|url=http://www.mises.org/fullstory.aspx?Id=1738|title="Ayn Rand's Contributions to the Cause of Freedom."|accessdate=2006-03-26}} Long also cites Barbara Branden's ''The Passion of Ayn Rand'' as the source for this claim.</ref> Later Objectivists, such as ], have claimed that Rand's economic theories are implicitly more supportive of the doctrines of ], though Rand herself was likely not acquainted with his work. | |||

| Commentators, including ], Nathaniel Branden, and ], have criticized Rand's focus on the importance of reason. Barnes and Ellis said Rand was too dismissive of emotion and failed to recognize its importance in human life. Branden said Rand's emphasis on reason led her to denigrate emotions and create unrealistic expectations of how consistently rational human beings should be.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|pp=173–176}} | |||

| ===Gender, sex, and race=== | |||

| Rand's views on ]s have created some controversy. While her books championed men and women as intellectual equals (for example, Dagny Taggart, the protagonist of ''Atlas Shrugged'' was a hands-on railroad executive), she thought that the differences in the physiology of men and women led to fundamental psychological differences that were the source of gender roles. Rand denied endorsing any kind of power difference between men and women, stating that metaphysical dominance in sexual relations refers to the man's role as the prime mover in sex and the necessity of male arousal for sex to occur.<ref name="Ayn Rand Answers">Rand, Ayn. Ayn Rand Answers: The Best of Her Q and A, (2006) ISBN 0451216652 </ref> According to Rand, "For a woman ''qua'' woman, the essence of femininity is hero-worship – the desire to look up to man." (1968) | |||

| === Ethics and politics === | |||

| Rand's theory of sex is implied by her broader ethical and psychological theories. Far from being a debasing animal instinct, she believed that sex is the highest celebration of our greatest values. Sex is a physical response to intellectual and spiritual values – a mechanism for giving concrete expression to values that could otherwise only be experienced in the abstract. In Atlas Shrugged, she writes "Tell me what a man finds sexually attractive and I will tell you his entire philosophy of life. Show me the woman he sleeps with and I will tell you his valuation of himself."<ref name="AtlasShruggedSex">Rand, Ayn. Atlas Shrugged, p453</ref> | |||

| In ethics, Rand argued for ] and ] (rational self-interest), as the guiding moral principle. She said the individual should "exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself".<ref>Wright, Darryl. {{" '}}A Human Society': Rand's Social Philosophy". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=163}}.</ref> Rand referred to egoism as "the virtue of selfishness" in her ].{{sfn|Kukathas|1998|p=55}} In it, she presented her solution to the ] by describing a ] theory that based morality in the needs of "man's survival <em>qua</em> man", which requires the use of a rational mind.{{sfn|Badhwar|Long|2020}} She condemned ethical altruism as incompatible with the requirements of human life and happiness,{{sfn|Badhwar|Long|2020}} and held the ] was evil and irrational,{{sfn|Gotthelf|2000|p=91}} writing in ''Atlas Shrugged'' that "Force and mind are opposites".{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=252}} | |||

| Rand's ethics and politics are the most criticized areas of her philosophy.{{sfn|Den Uyl|Rasmussen|1986|p=165}} Several authors, including ] and William F. O'Neill in two of the earliest academic critiques of her ideas,{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|pp=100, 115}} said she failed in her attempt to solve the is–ought problem.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=224}} Critics have called her definitions of ''egoism'' and ''altruism'' biased and inconsistent with normal usage.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=220}} Critics from religious traditions oppose her ] and her rejection of altruism.{{sfn|Baker|1987|pp=140–142}} | |||

| In a ] magazine interview, Rand stated that women are not psychologically suited to be President and strongly opposed the modern ] movement, despite supporting some of its goals.<ref name="new left">Rand, Ayn. The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution, (1993) ISBN 0-452-01125-6</ref> Feminist author ] called Rand "a traitor to her own sex," while others, including ] and the contributors to 1999's ''Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand,'' have noted Rand's "fiercely independent – and unapologetically sexual" heroines who are unbound by "tradition's chains... who had sex because they wanted to."<ref name="McLemee"/> | |||

| Rand's political philosophy emphasized ], including ]. She considered '']'' ] the only moral social system because in her view it was the only system based on protecting those rights.{{sfn|Gotthelf|2000|pp=91–92}} Rand opposed ] and ],<ref>Lewis, John David & Salmieri, Gregory. "A Philosopher on Her Times: Ayn Rand's Political and Cultural Commentary". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=353}}.</ref> which she considered to include many specific forms of government, such as ], ], ], ], and the ].<ref>Ghate, Onkar. {{" '}}A Free Mind and a Free Market Are Corollaries': Rand's Philosophical Perspective on Capitalism". In {{harvnb|Gotthelf|Salmieri|2016|p=233}}.</ref> Her preferred form of government was a ] republic that is limited to the protection of individual rights.{{sfn|Peikoff|1991|pp=367–368}} Although her political views are often classified as ] or ], Rand preferred the term "radical for capitalism". She worked with conservatives on political projects but disagreed with them over issues such as religion and ethics.{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=174–177, 209, 230–231}}{{sfn|Doherty|2007|pp=189–190}} Rand rejected ] as a naive theory based in ] that would lead to collectivism in practice,{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|pp=261–262}} and denounced libertarianism, which she associated with anarchism.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|pp=248–249}}{{sfn|Burns|2009|pp=268–269}} | |||

| In ''Atlas Shrugged,'' Rand writes that the "band on the wrist of naked arm gave her the most feminine of all aspects: the look of being chained." (One must note that this description is from the character Lillian Rearden, whose views certainly are not intended to reflect those of Ayn Rand.) This novel, along with ''Night of January 16th'' (1968) and ''The Fountainhead'' (1943), features sex scenes with stylized erotic combat that borders on ]. Rand herself noted that what ''The Fountainhead'' clearly depicted was "rape by engraved invitation." In a review of a biography of Rand, writer Jenny Turner opined, <blockquote>"the sex in Rand’s novels is extraordinarily violent and fetishistic. In ''The Fountainhead,'' the first coupling of the heroes, heralded by whips and rock drills and horseback riding and cracks in marble, is ‘an act of scorn ... not as love, but as defilement’ – in other words, a rape. (‘The act of a master taking shameful, contemptuous possession of her was the kind of rapture she had wanted.’ In ''Atlas Shrugged,'' erotic tension is cleverly increased by having one heroine bound into a plot with lots of spectacularly cruel and handsome men.)<ref name="Turner"/></blockquote> | |||

| Several critics, including Nozick, have said her attempt to justify individual rights based on egoism fails.<ref>Miller, Fred D., Jr. & Mossoff, Adam. "Ayn Rand's Theory of Rights: An Exposition and Response to Critics". In {{harvnb|Salmieri|Mayhew|2019|pp=135–142}}</ref> Others, like libertarian philosopher ], have gone further, saying that her support of egoism and her support of individual rights are inconsistent positions.<ref>Miller, Fred D., Jr. & Mossoff, Adam. "Ayn Rand's Theory of Rights: An Exposition and Response to Critics". In {{harvnb|Salmieri|Mayhew|2019|pp=146–148}}</ref> Some critics, like ], have said that her opposition to the initiation of force should lead to support of anarchism, rather than limited government.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=260, 442 n33}}{{sfn|Gladstein|1999|p=116}} | |||

| Another source of controversy is Rand's view of ]. According to remarks at the Ford Hall forum at ] in 1971, Rand's personal view was that homosexuality is "immoral" and "disgusting."<ref name="Ford"> Ford Hall forum remarks, cited in {{cite web|url=http://www.noblesoul.com/orc/bio/biofaq.html#Q5.2.6|title="Ayn Rand Biographical FAQ: Ayn Rand and Homosexuality"|accessdate=2006-03-24}}</ref> Specifically, she stated that "there is a psychological immorality at the root of homosexuality" because "it involves psychological flaws, corruptions, errors, or unfortunate premises."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.noblesoul.com/orc/bio/biofaq-notes.html#n5.2.6-1|title=Notes, The Ayn Rand Biographical FAQ|accessdate=2006-03-24}}</ref> A number of noted current and former Objectivists have been highly critical of Rand for her views on homosexuality.<ref>Varnell, Paul.{{cite web|title="Ayn Rand and Homosexuality"|url=http://www.indegayforum.org/authors/varnell/varnell118.html|accessdate=2006-03}} at the Indegay Forum, originally published in the ] Dec. 3, 2003. </ref> Others, such as Kurt Keefner, have argued that "Rand’s views were in line with the views at the time of the general public and the psychiatric community," though he asserts that "she never provided the slightest argument for her position, because she regarded the matter as self-evident, like the woman president issue."<ref> Keefner, Kurt. {{cite web|url=http://www.nyu.edu/projects/sciabarra/essays/homo/atlasphere.htm|title="Sciabarra on Ayn Rand and Homosexuality"|date=]}} A review of | |||

| Chris Matthew Sciabarra’s ''Ayn Rand, Homosexuality, and Human Liberation ''(2003, Leap Publishing)</ref> In the same appearance, Rand noted, "I do not believe that the government has the right to prohibit . It is the privilege of any individual to use his sex life in whichever way he wants it."<ref name="Ford"/> | |||

| === Relationship to other philosophers === | |||

| Rand defended the right of businesses to discriminate on the basis of ], ], or any other criteria. Rand's defenders argue that her opposition to government intervention to end private discrimination was motivated by her valuing ] above ] (due to a rejection of the concept of "collective rights") and therefore her view did not constitute an endorsement of the morality of the prejudice ''per se''. Rand argued that no one's rights are violated by a private individual's or organization's refusal to deal with him, even if the reason is irrational. | |||

| {{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=300 | |||

| | image1=Aristotle Altemps Inv8575.jpg|alt1=Marble statue of Aristotle | |||

| | image2=Immanuel Kant portrait c1790.jpg|alt2=Painting of Immanuel Kant | |||

| | footer=Rand claimed ] (left) as her primary philosophical influence, and strongly criticized ] (right). | |||

| }} | |||

| Except for Aristotle, ] and ], Rand was sharply critical{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=111}} of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her.{{sfn|O'Neill|1977|pp=18–20}}{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=11}} Acknowledging Aristotle as her greatest influence,{{sfn|Burns|2009|p=2}} Rand remarked that in the ] she could only recommend "three A's"—Aristotle, Aquinas, and Ayn Rand.{{sfn|Sciabarra|2013|p=11}} In a 1959 interview with ], when asked where her philosophy came from, she responded: {{qi|Out of my own mind, with the sole acknowledgement of a debt to Aristotle, the only philosopher who ever influenced me.}}{{sfn|Podritske|Schwartz|2009|pp=174–175}} | |||